Abstract

Despite co-creation being considered a valuable strategy for incremental changes towards more sustainable activities and consumers’ declared interest, hospitality businesses still did not experience the expected level of client engagement in their service interactions. Therefore, the primary purpose of this paper is to examine the nature of value co-creation and its antecedents and consequences within the hotel industry context through the lens of sustainability. Integrated marketing communication (IMC) and ecological knowledge are examined as factors that enhance value co-creation. Satisfaction is observed as a mediator of the relationship between value co-creation and customer loyalty. A closed-response, in-person structured survey was used to collect data from 303 guests of hotels located in Ukraine. The hypotheses were tested using the partial least squares method. The findings reveal that company IMC causes a higher impact on value co-creation. However, ecological knowledge does not seem to affect value co-creation. Furthermore, value co-creation shows a significant influence on customer satisfaction, and directly and indirectly affects loyalty through satisfaction. This study’s theoretical and practical implications are included to assist both scholars and practitioners in the hospitality industry in enriching their understanding of effective value co-creation and communication strategies related to sustainability to increase customer satisfaction and loyalty.

1. Introduction

While more and more tourists aspire to be environmentally friendly, many firms, hotels in particular, struggle to engage with their customers through sustainable practices (e.g., towel reuse, energy preservation programs), and have difficulties in obtaining the expected financial increases from “green” products and services [1,2,3,4] More research is needed regarding behavioral approaches that encourage customers to engage in sustainable practices in service companies [5].

It is believed that value co-creation can cause better acceptance of company environmentally friendly practices by tourists through contribution and collaboration [1,6,7], thus creating competitive advantages and generating profitability [8,9]. According to [10], customer co-creation contributes to firm’s results, as it establishes stronger relationships and increases their involvement. Similarly, when customers can co-create by sharing their experience and giving/receiving feedback while collaborating with the hotel, they are more likely to gain a higher level of satisfaction with their stay and to be more loyal to the hotel [8,11]. However, while most studies tried to explain the benefits of co-creation, very few of them investigated its antecedents in the tourism context, e.g., [8], or analyzed the dimensions from the perspective of sustainability in tourism [12,13].

As identified by various authors, effective marketing communication between service providers and their customers [9,14,15] and sufficient level of knowledge [9,12,16,17] are important antecedents for clients’ participation in the co-creation process [18]. Inefficient usage of communication tools and the lack of companies’ technical competence [3,4,19] generates a theoretical and practical need to investigate the role and the effectiveness of hotel’s marketing communication related to sustainability on value co-creation from the perspective of the client. This article investigates the sustainability communication of hotels through the lens of integrated marketing communication by focusing on the synergy effect that the total persuasiveness of two or more integrated communication elements brings [20]. Then again, there is evidence that consumers who do not have enough ecological literacy are not able to appreciate these hotels’ “green” practices [21]. Clients who are involved in co-creation processes should be persons who have a high level of knowledge regarding sustainability issues [5,6], as it leads to active participation in value co-creation process and corresponds with a certain level of expertise bases on which to start collaborating [9,16,22]. Although previous research includes the concept of prior knowledge as an antecedent of the value co-creation process [9,16], few works [6] highlighted the importance of ecological knowledge for value co-creation in sustainability scope. Therefore, there are theoretical and practical needs to investigate IMC and ecological knowledge in relation to value co-creation in the hotel sustainability context [5,18].

Last year’s research works primarily focused on studying value co-creation outcomes, such as satisfaction and loyalty, e.g., [8,11,23,24]. However, Refs. [13,18] claimed that further investigation is necessary to uncover customers’ responses to co-creation, particularly in terms of sustainability [6,12]. Moreover, empirical evidence suggests that the relationship between value and loyalty can be mediated by the customer satisfaction variable [25,26,27,28]. To better understand the nature of value co-creation consequences, this study aims at examining value co-creation–satisfaction–loyalty interactions in the frame of sustainability within the hotel industry. In this way, this article also responds to the priority research question of Marketing Science Institute: “what are the most effective strategies to drive deeper, lasting customer engagement/loyalty with the firm?” [29] (p. 2).

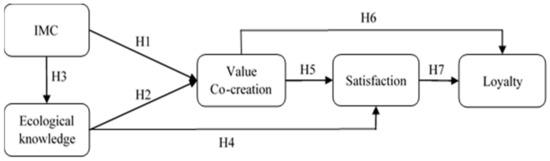

Following up on calls for further research, this study tests a comprehensive model that includes simultaneously antecedents and consequences of customer value co-creation focusing on sustainability in hospitality businesses. Consequently, our objectives are: firstly, to evaluate the influence of IMC and guests’ ecological knowledge on value co-creation; secondly, we are interested in seeing how value co-creation interacts with satisfaction and loyalty; thirdly, we examine the mediation role of satisfaction on co-creation–loyalty relations. The results obtained provide relevant information to hotel managers and may assist in guiding them in designing effective value co-creation and communication strategies related to sustainability to increase customer satisfaction and loyalty. These factors demonstrate the importance and originality of this study.

2. Conceptual Background

2.1. Value Co-Creation and Sustainability

According to [30], the value co-creation takes place from the perspective of the dominant logic of service, where the consumer must be conceived as a more active agent in the value creation process. Those authors suggested that customers should participate in the definition of the product or service offer through knowledge sharing, co-design, or shared production to create value. In the tourism context, the concept of co-creation is particularly relevant, as it helps tailoring the service to the customers’ particular needs, and hence, assists with creating a unique experience, which is crucial for tourism service providers to remain competitive [8,31]. Ref. [32] defines value co-creation within the context of the hotel industry as “actors’ appraisal of the meaningfulness of a service by assessing what is contributed and what is realized through collaboration” (p. 72).

In the frame of sustainability, co-creation can be a possible way to develop new sustainability innovations and introduce them into the practice successfully [1,6,9,10]. Consequently, by being involved and participating in the sustainable practices developed by the hotel, guests are able to co-create value. Ref. [12] (p. 3) proposes an original concept of “green value co-creation”, which is defined as “the active sharing of environmental ideas between a company and its partners and participation in one or more production or consumption stages to create value”. However, since there are limited literary and empirical studies about the value co-creation in the sustainability context, e.g., [6,12,13], this area of knowledge requires further research.

In this study, value co-creation in the context of sustainability is treated as multidimensional concept [13] that consists of different elements, namely: meaningfulness, collaboration, contribution, recognition, and affective response [32]. Meaningfulness is an individual’s (agent or beneficiary) belief in the importance and true benefit of the service. When one believes that the process of value co-creation is meaningful, the result is greater joint value. Collaboration is understood as a sense of open alliance and cooperation for mutual benefit between two or more actors involved in co-creation. Contribution is a belief regarding the degree to which a beneficiary shares his or her own resources to achieve the desired results. Recognition refers to acknowledgment and explains relational and consumer-centered nature of co-creation. Finally, the affective response is defined as the general emotional reaction that one has towards co-creation and is an essential dimension of the concept. All this allows us to observe value co-creation from the perspective of what is given and what is received through collaboration. While providing service along with sustainability practices, tourist companies and their clients can find the process meaningful, collaborate, contribute, receive recognition, and generate affective response to co-create “green” value [12]. This perspective, explicitly applied to the field of hospitality businesses in the tourism sector, offers a new approach to understanding the co-creation process, which considers that the more resources and efforts that are invested in the process, the more the result is valued [32].

2.2. Integrated Marketing Communication and Ecological Knowledge as Value Co-Creation Antecedents

To be recognized and to gain additional competitive advantage, hotels need to communicate about their environmentally friendly practices [4,19,33]. However, communicating effectively about sustainability to create necessary impact is challenging, and generated an ongoing debate around how to design an effective environmental communication strategy [4].

Many scholars agree that IMC is an effective tool which delivers consistent messages that are critical for company success, as unclear and fragmented messages about the firm activity might confuse customers and endanger the provided service [34]. Ref. [20] also pointed out the importance of companies applying IMC strategy, as the combination of multiple elements of the marketing communication mix enables a synergetic effect leading to a higher persuasive power of the message. As a result, communicating about sustainability through IMC might be an option to reduce the low-effectiveness of current sustainability communication. The concept of IMC for sustainability is a novel construct that has recently emerged [35,36]. Communicating “green” through IMC tools means implementing marketing activities that integrate opportunities for public welfare, environmental preservation, and balanced economic development with a view to increasing the consumption value of a product or service through the company’s communication with market participants using distribution channels [35].

Marketing communication lies at the foundation of most service interactions [18] and it is an important element in a company’s ability to manage value co-creation [9]. As indicated by [37], communication is capable of achieving a higher level of collaboration and involvement by tourists. Additionally, as stated by various authors, effective and active communication between service providers and their customers is a crucial antecedence for clients’ participation in the co-creation process [8,14,15]. Nevertheless, to the best of our knowledge, no studies investigated the effect of company IMC on customer value co-creation activity. Therefore, taking into account all the mentioned above, the first hypothesis proposed is:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

IMC for sustainability has a positive impact on a guest’s value co-creation.

Yet, ecological knowledge must be considered by all participants of the co-creation process, since knowledge is one of the key aspects of the service and the ability of all parties to create value [9,17,18]. Prior knowledge influences customer readiness to engage in co-creation [16], increasing their level of expertise [22]. Successful “green” value co-creation process requires participants with a high degree of experience and knowledge regarding sustainability issues and are strongly involved in these topics [6]. Consumers who do not have enough ecological knowledge could not appreciate the ecological practices of hotels [21], nor, therefore, co-create the value [6,7,12]. Ecological knowledge is related to an understanding and concern regarding natural environments, and encourages an individual’s stronger sense of responsibility for environmental protection [38]. This suggests the important role of ecological knowledge for hoteliers when planning their environmentally friendly campaigns. Raising such knowledge may change guests’ attitudes and behavior toward hotels “green” practices [39]. Correspondingly, it is expected that a high level of ecological knowledge will lead to active collaboration in the process of value co-creation by the guest. Thus, the second hypothesis proposed is:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Ecological knowledge has a positive impact on a guest’s value co-creation.

At the same time, companies need to enhance the effectiveness of their sustainability communication; for example, [21] identifies the necessity of raising tourists’ ecological literacy to gain their recognition of companies’ efforts around environmentally friendly practices. Ref. [3] indicated that communication related to sustainability aims to make consumers aware of the availability of sustainable travel products, to inform consumers about how these offers meet their needs as well as meeting sustainability criteria, and ultimately, encourage sustainable purchases. As stated by various authors, a clear and consistent communication about ecofriendly practices can help raise guests’ ecological awareness and develop a positive attitude toward the hotel [33,40,41]. Therefore, we might expect that hotel sustainability communication employing IMC would serve as a decisive factor for enhancing guests’ ecological knowledge. Hence, the third hypothesis is developed:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

IMC for sustainability has a positive impact on a guest’s ecological knowledge.

2.3. Satisfaction and Ecological Knowledge

Lately, there was increased interest by scholars on studying the concept of satisfaction by connecting it to environmentally friendly practices in the hospitality industry [40,41,42]. According to the findings of [43], clients are likely to be more satisfied if the company develop socially and environmentally responsible initiatives. However, customers that lack ecological knowledge are not able to appreciate these kinds of initiatives [21], nor will they experience satisfaction with the stay at this hotel. Following knowledge-attitude-behavior model, previous investigations demonstrate that a higher level of client environmental concern corresponds with the development of positive behavioral intentions towards the “green” hotels [39,44], and in turn, behavior based on pro-environmental values leads to satisfaction [45]. A similar finding was suggested by [46], where ecofriendly behavior enhances tourist satisfaction. Based on all the considerations above, this paper suggests that guests’ ecological knowledge affects their satisfaction with the stay. Thus, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Ecological knowledge has a positive impact on a guest’s satisfaction.

2.4. Value Co-Creation—Satisfaction—Loyalty Relationships

A large body of empirical evidence shows that customer participation in co-creation activity increases client satisfaction, e.g., [8,11,24,47], and loyalty toward the service company [8,11,14,23].

In their study, [8] indicate that customers’ engagement in the service development process creates the perception of belonging to the company that, in turn, is reflected in client’s satisfaction and loyalty to the company. In addition, via customers’ involvement, a final product or service can be better adapted to clients’ needs, leading to greater customer satisfaction [47].

As with satisfaction, customer loyalty is a crucial factor for a company’s success, as it represents the customer’s willingness to build a long-term relationship with a company, and to recommend it to others [23]. Loyalty is also considered an outcome of value co-creation activity [8,24], so it is reasonable to assume when customers can co-create value, they are more likely to revisit the same hotel again and to recommend it to others as a sustainable one.

Furthermore, it was shown that customers tend to develop greater levels of loyalty toward a specific company when they are satisfied with its performance [8,11,40,48].

In addition, various works indicate a description of loyalty through the value-satisfaction-loyalty chain where satisfaction is the mediator e.g., [25,26,27,28,49]. However, there is no empirical research that takes the mediating role of satisfaction into consideration when investigating value co-creation and customer loyalty interactions in hospitality in terms of sustainability. Limited studies considered perceived value as a core of customer value creation [25,26,28,48].

Therefore, to respond to the recent research call [13] and shed light on how value co-creation, in terms of sustainability practices, interacts with customer satisfaction and loyalty; to understand the level of impact of satisfaction on loyalty, and to examine the mediation role of satisfaction on co-creation-loyalty relations, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Value co-creation has a positive impact on a guest’s satisfaction.

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

Value co-creation has a positive impact on a guest’s loyalty.

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

Satisfaction has a positive impact on a guest’s loyalty.

Hypothesis 8 (H8).

Satisfaction positively mediates the relationship between value co-creation and loyalty.

Figure 1 represents the proposed conceptual model for this research.

Figure 1.

Theoretical model and hypothesis.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

To collect the information to test these hypotheses, a quantitative analysis was conducted through an ad hoc, closed-response, structured, in-person survey among 327 tourists who stayed in three-, four-, and five-star hotels in Kyiv (Ukraine). To design the research sample, a nonprobability convenience sampling procedure was chosen, as there was no access to a census of hotel clients, and it was not possible to determine the probability that an element of the population must belong to the sample [50]. Current hotel customers and people who stayed in the hotel within the last year were asked to participate. Clarifications about the study objectives and voluntary consent were obtained from all selected participants. The paper-based questionnaire included three sections: the first explained the research purpose, the second covered the measurement scales for the model variables, and the third collected sociodemographic information. In total, 303 valid questionnaires were gained during the month of August 2018.

3.2. Sample Profile

Regarding the demographic profile of the respondents, 42.9% were men and 57.1% women; 40.9% of the interviewees were between 18 and 25 years of age, 40.3% were between 26 and 35, 10.6% were between 36 and 45, and 8.2% were over 46. In terms of education, the majority had a master’s degree (55.8%) and a bachelor’s degree (26.4%). Concerning their employment status 44.9% were employed, and 20.5% were entrepreneurs. Regarding monthly income, 50.5% of respondents earned less than 1000 euros, 37.6% earned between 1000 and 3000, and 11.9% had no salary or did not want to disclose it. As for the purpose of the trip, 51.2% were on vacation, 32.7% on business and the rest (16.2%) for other motives. Finally, 92.7% were of Ukrainian nationality, and the remaining 7.3% of other nationalities.

3.3. Measurement Development

Validated measurement scales used from previous studies were adapted for hotels and for the sustainability framework. Ecological knowledge was measured as a seven-item index used by [21] for tourism industry. Regarding the IMC, four items were taken from dimension “unified communications for consistent message and image” from [51]. Since the original scale was used to evaluate the IMC’s perception from the company managers point of view, we decided to retain only the first dimension of the proposal under the belief that guests are qualified to express an opinion about said indicators and not the rest. Furthermore, it represents the key aspect of the IMC: the consistency of the message, associated with the ideas of coherence and uniformity [51]. The items used for value co-creation were taken and adapted from the five-dimensional scale proposed by [32]. Next, satisfaction was evaluated using six items suggested by [41,52]. These elements were combined to reflect general satisfaction with the hotel stay (3 items) and satisfaction with the hotels that denote environmentally friendly attitude (3 items). Finally, loyalty was measured by means of the three-item scale, based on [53,54] loyalty scales. Seven-point Likert scales were used, with 1 indicating complete disagreement and 7 indicating complete agreement with the statement. Three versions of the questionnaire were developed, in Ukrainian, Russian, and English, and all were translated by native speakers and back-translated to verify the accuracy of the translations.

4. Results

We used Smart PLS 3 to perform structural equation modelling by following a two-stage analytical procedure [55]. The variance-based structural equation model (SEM) was preferred, as it is well suited to the characteristics of the research and the nature of the collected data [55]. Primarily, the measurement scales were developed with Likert-type scales, and the data have a nonnormal distribution, which is handled well by Smart PLS. Moreover, it is recommended to use the partial least square (PLS) method when the studied construct is complex and/or relatively new and changing [55,56], as is the case with IMC for sustainability, ecological knowledge, and value co-creation.

4.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Firstly, we examined the measurement model by means of confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) by checking for the validity and reliability of the measures, and secondly, we examined the structural model.

The measurement model for value co-creation construct, as second-order factor proposed by [32], was estimated using repeated indicator approach [57]. The results of the CFA allowed retaining four dimensions to explain value co-creation in terms of meaningfulness, collaboration, contribution, and affective response. The recognition dimension was deleted as it did not meet the necessary value of the HT/MT ratio [58].

For all remaining factors, total standardized loadings were analyzed to assess convergent validity. As presented in Table 1, all the loadings were statistically significant for all items and higher than 0.6, except for one indicator. Since the elimination of this item did not improve the results, we decided to maintain it [55]. Moreover, to confirm the reliability of all scales both the composite reliability and the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient were estimated, the values of which were higher than the recommended values of 0.7 [59] for all constructs. In the same way, each construct was considered to possess convergent validity as the value of average variance extracted analysis (AVE) was higher than the recommended value of 0.5 [60]. Therefore, the reliability of the scales and the convergent validity of the proposed constructs were confirmed.

Table 1.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis results.

Next, as presented in Table 2, the discriminant validity was established through (1) AVE and (2) the ratio of HT/MT (Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio of Correlations). Firstly, we found that the square of the correlation calculated between two factors was less than the AVE of each factor, and no indicator had a significant influence on another factor that does not correspond to it [60]. Secondly, the same rule was confirmed with the ratio of HT/MT that was less than 0.85 for each factor, which means that the monotrait–heteromethod MT correlations (relations between the indicators of the same construct) are greater than the heterotrait–heteromethod HT (relations between the indicators that measure different constructs) [58].

Table 2.

Discriminant validity.

4.2. Structural Model and Hypotheses Testing

Finally, once the validity had been confirmed, we calculated the structural equations model using partial least squares (PLS) regression. Firstly, explanatory and predictive power of the model were verified through coefficients of determination R2 and cross-validated redundancy indices Q2. As depicted in Table 3, all the scores were above the recommended level of 0.10 for R2 [61] and above 0 for Q2 [62], which suggests that the predictive relevance of the proposed model is satisfactory. Secondly, the significance of the structural relationships was analyzed through the bootstrapping algorithm based on 5000 runs [55].

Table 3.

Results of structural equation model.

The results show that the first hypothesis is accepted, as positive and significant relationship is found between hotel’s IMC for sustainability and value co-creation (β = 0.440, p < 0.01; H1), with t-value of 8.873. In contrast, the relationship between ecological knowledge and value co-creation does not seem to be significant (β = 0.030, p > 0.05; H2), which represents t-values of 0.563. Concerning the third hypothesis, a positive relationship is found between IMC and customers’ ecological knowledge (β = 0.477, p < 0.01; H3), with the t-value of 10.327. Besides, our findings reveal that the impact of ecological knowledge on satisfaction is significant (β = 0.357, p < 0.01; H4) with the t-value of 6.423, which leads to the acceptance of H4. Moreover, it is found that value co-creation exerts a positive influence on both satisfaction (β = 0.229, p < 0.01; H5) and loyalty (β = 0.155, p < 0.01; H6), with respective t-values of 4.211 and 2.980, thus providing support for H5 and H6. Finally, the results show that H7 is also accepted, as satisfaction positively influences loyalty (β = 0.517, p < 0.01; H7), with the t-value of 11.352.

4.3. Mediation Analysis Testing

Additionally, in line with H8, our findings provide empirical support for the mediating role of customer satisfaction in the co-creation-loyalty model. PLS-SEM bootstrapping confidence intervals were used to test indirect effects [63]. Since both the direct and indirect effects between co-creation and loyalty are significant, we conclude that satisfaction partially mediates this relationship. The product of the direct and the indirect effect (0.155 × 0.119 = 0.019) shows complementary partial mediation, as its sign is positive [55]. The results obtained are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Mediation role of Satisfaction.

More specifically, customer satisfaction serves as a complementary mediator. As total effect showed (βtotal = 0.274; t = 6.892; p < 0.01), higher levels of co-creation increased customer loyalty directly but also increased customer satisfaction, which in turn leads to customer loyalty. Hence, value co-creation’s effect on loyalty is explained by satisfaction.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical and Managerial Implications

The findings derived from the present work aim to reduce the gaps identified in the literature in the area that explains antecedents and consequences of value co-creation in the hotel industry. Thereby, this work examines the complex nature of value co-creation, applying it to the sustainability context [5,13], and observes it as a driver of customer loyalty, responding in this way to the priority research question of Marketing Science Institute [29]. A series of conclusions emerged based on the results obtained.

Firstly, in line with the work of [8,15,37], which support the statement that active and effective communication enables the value co-creation process, the findings of this study indicate that the degree to which hotels implement IMC positively influences value co-creation. According to the results obtained, value co-creation construct is defined by four dimensions: meaningfulness, collaboration, contribution, and affective response. Thus, the perception of IMC provided by the hotel creates a positive effect when it refers to the importance of service, cooperating, sharing resources, and emotionally responding to the process of value co-creation, involving the guest on the development of hotel’s sustainable practices.

Secondly, the findings do not support the relationship between ecological knowledge and value co-creation; that is, the level of guest ecological knowledge does not play a role in the collaboration process around the hotel’s ecological practices. However, the existing body of literature suggests the opposite, confirming that consumers with less ecological knowledge are less likely to appreciate the ecological practices of hotels [21] or to engage in the value co-creation process [6,7,12,16]. We should also consider the study of [64], which obtained a negative result regarding the impact of environmental concern, revealing that consumers with high concern for the environment do not consider it a factor of great importance when there are other external barriers to sustainable consumption (such as price, availability, or the practical feasibility) [39]. Furthermore, geographic factors possibly impacted our results; the study was carried out in Ukraine, a country where both the hotel industry and their clients only began to become familiar with the need to be environmentally conscious, which may explain the low awareness of environmental issues.

Third, the relationships between value co-creation, satisfaction and loyalty are confirmed, meaning that a higher degree of value co-creation leads to a higher level of guest satisfaction and loyalty towards the hotel. This finding is in accordance with those obtained by [8,11,23,47], although these studies were not conducted within the framework of sustainability in the hospitality industry. Furthermore, due to the complex and multidimensional nature of value co-creation construct [13], and in line with the results derived from our work, we can conclude that meaningfulness, collaboration, contribution, and affective response explain the satisfaction and loyalty of the guest. Clients who have the opportunity to co-create value while sharing the experience, giving/receiving feedback, contributing and collaborating with staff on the hotel’s sustainable activities and find this process worthwhile and interesting get a higher level of satisfaction with the stay and are more loyal to the hotel. Similarly, there is a significant connection between customer satisfaction and loyalty that corresponds with outcomes obtained by [8,11,40,48].

In addition, the results demonstrate that satisfaction plays a mediating role in the value-co-creation-loyalty chain, which fits with findings reported by [25,26,27,28] regarding value-satisfaction-loyalty relations. In our study, satisfaction serves as a complementary mediator since co-creation impacts on customer loyalty not only directly, but also in terms of satisfaction. In other words, value co-creation’s effect on loyalty is mainly explained by satisfaction. Thereby, because customers experience a positive affective response during the value co-creation process, they develop loyalty to the hotel.

Finally, the perception of IMC for sustainability influences guests’ ecological knowledge. Confirming this relationship constitutes a notable contribution to the scope of this research and complements previous works, e.g., [3,40,41], which affirm that persuasive communication regarding sustainability plays an important role, triggering environmentally friendly decisions. Thus, it is possible to conclude that IMC for sustainability enhances the ecological knowledge of guests by harnessing the synergetic effect of various communication elements. Furthermore, clients’ ecological knowledge positively affects their level of satisfaction with their stay at hotels that implement environmentally friendly practices, which highlights its relevance when defining the result variable, i.e., satisfaction. These findings complement results obtained by [43,44,45], which emphasize the importance of positive perceptions about sustainable practices in guest satisfaction. Therefore, clear, coherent, and integrated communication can help to educate and elevate guest’s ecological literacy and to develop a positive attitude toward the hotel through satisfaction [40].

The results of this study can be used to propose a set of managerial implications. Firstly, by understanding the different value co-creation dimensions, hoteliers might define what actions set up value co-creation during service interactions and focus on their enhancement within both customers and their service employees. Besides, identifying the antecedents of value co-creation allows managers to improve these service actions to generate more value for customers and the company itself, especially if the latter accounts value co-creation as a competitive advantage. In support of our own and extant literature findings, communication about sustainability plays an important role in leading successful value co-creation activity. The findings reveal that hoteliers need to pay attention to how their company builds IMC strategy and connects through different communication channels with their clients promoting “green” initiatives. For instance, sustainable hotels should not only use public relations and advertising to communicate their environmentally friendly initiatives to customers, but also actively participate in ecological forums and events, sponsor environmental programs, and increase their presence on social networks. Active dialog through these communication channels might create valuable collaboration opportunities with their existing and potential guests enhancing in this way customer and company value in a sustainability context. To achieve this goal, it is crucial to create two-way communication between guests and hotel managers, with company employees as essential mediators via offline and online communication tools, transmitting information about environmentally friendly practices between both parties. However, hotel managers should carry out “green” communication campaigns carefully because guests’ reactions to “green washing” could be unfavorable and create a certain level of skepticism.

Secondly, we draw from our study that the hotels need to support, interactively communicate about, and provide the opportunity for guests to collaborate on co-creation of environmentally friendly initiatives to gain guests’ satisfaction and loyalty. This could be accomplished through service customization, experience sharing, and opinion discussion before, during, and after participating in the hotel’s sustainable practices, as the guests are often unaware of these types of activities and the impact their stay has on the environment. Hotels might create an online community, use an engaging platform, or simply encourage direct interaction between the guest and hotel staff. Since the results of our study illustrate that the more the guests get involved in co-creation activities, the more value they attach to the process, which reflects on their degree of satisfaction with the company and loyalty. Consequently, the value generated during this co-creative process allows hotels to gain greater competitive advantages usually presented by their customers’ loyalty, especially important in terms of company sustainability development.

Finally, given empirical evidence where IMC for sustainability increases customer ecological knowledge, hoteliers are encouraged to provide their guests with the necessary information about “green” and environmental issues and create a motivational program for clients to take action (e.g., bonus program for towel reuse, discounts for the bus, or bicycle use) informing clients about its advantages through different channels of communication. As our findings reveal, this strategy will lead to customer satisfaction with the stay and lasting loyalty toward the hotel, which is one of the primary goals of the hospitality company.

5.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

The results of this study are subject to the following limitations that could be amended in future research. Firstly, this study applies the four-dimension construct of value co-creation in hospitality that might limit the conceptualization of the value co-creation construct in a sustainability context. Further research might test a different higher-order value co-creation measurement model to enhance theoretical contributions by applying it to the sustainability context (e.g., green coproduction, green value-in-use) [12,24]. Moreover, it would be interesting to test the multiple mediation and moderation effects of value co-creation on the existing relationships, considering the degree of customer engagement in the process. Given the novelty and complex nature of the value co-creation constructs, it would also be interesting to analyze the possible opposite direction relationships to those established in this study. For example, future studies might test an alternative model to see whether the level of ecological knowledge and IMC perception are driven by customer participation in the value co-creation process.

Secondly, we would expect to find a positive relationship between guests’ ecological knowledge and value co-creation in countries with high levels of environmental consciousness. An ecological knowledge variable could also play a moderating role in the proposed model when comparing samples with high and low levels of customers’ environmental literacy.

Thirdly, given the limited sample design and restricted geographical scope of the study, it would be interesting to compare the results of this study with those obtained in other countries, thereby introducing a national culture variable into the theoretical model. Furthermore, we would like to highlight opportunities to advance this line of research by introducing new variables into the proposed model. For example, it would be interesting to introduce the notion of brand equity, given the evidence in the literature on its relationships with other variables in this study. Additionally, loyalty could be measured using a multidimensional measurement scale that includes WOM, attachment, and revisiting intention components to better understand customers’ behavioral intentions towards sustainable hotels. Moreover, given the diversity of the hotel categories in the present paper, it would be advisable to introduce the hotel category through the number of stars in the analysis to eliminate possible biases in the results, or to achieve a sufficient sample size within the same category of the hotel. Similarly, given that this study used a convenience sampling procedure and the sample profile is biased in age representativeness, future studies might introduce the category of a generational cohort into the model to test for differences that the age of the tourists might show. Finally, this research only looked at outcomes in the hospitality industry—future research should assess other service settings to increase the generalization of the findings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B. and I.G.-S.; Methodology, M.B. and I.G.-S.; Validation, M.B. and I.G.-S.; Formal Analysis, M.B.; Investigation, M.B. and I.G.-S.; Data Curation, M.B.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, M.B. and. I.G.-S.; Writing—Review and Editing, M.B. and I.G.-S.; Visualization, M.B. and I.G.-S.; Supervision, I.G.-S.; Project Administration, I.G.-S. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation for this study (National R&D Plan PID2020-112660RB-I00).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Font, X.; English, R.; Gkritzali, A.; Tian, W.S. Value co-creation in sustainable tourism: A service-dominant logic approach. Tour. Manag. 2021, 82, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabler, C.B.; Butler, T.D.; Adams, F.G. The environmental belief-behaviour gap: Exploring barriers to green consumerism. J. Cust. Behav. 2013, 12, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tölkes, C. The role of sustainability communication in the attitude–behaviour gap of sustainable tourism. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2020, 20, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehrli, R.; Priskin, J.; Demarmels, S.; Schaffner, D. How to communicate sustainable tourism products to customers: Results from a choice experiment. Curr. Issues Tour. 2014, 20, 1375–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, A.L.; Field, J.M.; Fotheringham, D.; Subramony, M.; Gustafsson, A.; Lemon, K.N.; Huang, M.H.; Mccoll-Knnedy, J.R. Service Research Priorities: Managing and Delivering Service in Turbulent Times. J. Serv. Res. 2021, 24, 329–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, M. Fostering sustainability by linking co-creation and relationship management concepts. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Haglund, L.; Kallgren, H.; Revahl, M.; Hultman, J. Swedish air travellers and voluntary carbon offsets: Towards the co-creation of environmental value? Curr. Issues Tour. 2009, 12, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grissemann, U.S.; Stokburger-Sauer, N.E. Customer co-creation of travel services: The role of company support and customer satisfaction with the co-creation performance. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1483–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, A.F.; Storbacka, K.; Frow, P. Managing the co-creation of value. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2008, 36, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. Co-creation experiences: The next practice in value creation. J. Interact. Mark. 2004, 18, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Opata, C.N.; Xiao, W.; Nusenu, A.A.; Tetteh, S.; Asante-Boadi, E. The impact of value co-creation on satisfaction and loyalty: The moderating effect of price fairness (empirical study of automobile customers in Ghana). Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2019, 32, 1167–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.H. Do green motives influence green product innovation? The mediating role of green value co-creation. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Verleye, K.; Hatak, I.; Koller, M.; Zauner, A. Three Decades of Customer Value Research: Paradigmatic Roots and Future Research Avenues. J. Serv. Res. 2020, 23, 409–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auh, S.; Bell, S.J.; McLeod, C.S.; Shih, E. Co-production and customer loyalty in financial services. J. Retail. 2007, 83, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsaro, D. Capturing the broader picture of value co-creation management. Eur. Manag. J. 2019, 37, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Gannon, M.J.; Muskat, B.; Taheri, B. A serious leisure perspective of culinary tourism co-creation: The influence of prior knowledge, physical environment and service quality. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 2453–2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Maglio, P.P.; Akaka, M.A. On value and value co-creation: A service systems and service logic perspective. Eur. Manag. J. 2008, 26, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neghina, C.; Caniëls, M.C.J.; Bloemer, J.M.M.; van Birgelen, M.J.H. Value co-creation in service interactions. Mark. Theory 2015, 15, 221–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Buckley, R. Carbon labels in tourism: Persuasive communication? J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 111, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Marshall, R. Are two arguments always better than one? Eur. J. Mark. 2016, 50, 1399–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, C.C.; Lu, A.C.C.; Huang, T.T. Drivers of consumers’ behavioral intention toward green hotels. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 1134–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, F.C.; Trimi, S.; Hong, S.G. Motivation triggers for customer participation in value co-creation. Serv. Bus. 2019, 13, 557–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, O.; Markovic, S.; Bagherzadeh, M.; Singh, J.J. Co-creation: A Key Link between Corporate Social Responsibility, Customer Trust, and Customer Loyalty. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 163, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moise, M.S.; Gil-Saura, I.; Ruiz-Molina, M.E. Implications of Value Co-Creation in Green Hotels: The Moderating Effect of Trip Purpose and Generational Cohort. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallarza, M.G.; Arteaga, F.; Gil-Saura, I. Customer value in tourism and hospitality: Broadening dimensions and stretching the value-satisfaction-loyalty chain. Tour. Manag. Persp. 2019, 31, 254–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallarza, M.G.; Arteaga-Moreno, F.; Del Chiappa, G.; Gil-Saura, I. Intrinsic value dimensions and the value-satisfaction-loyalty chain: A causal model for services. J. Serv. Mark. 2016, 30, 165–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, S.Y.; Shankar, V.; Erramilli, M.K.; Murthy, B. Customer value, satisfaction, loyalty, and switching costs: An illustration from a business-to-business service context. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2004, 32, 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tournois, L. Does the value manufacturers (brands) create translate into enhanced reputation? A multi-sector examination of the value-satisfaction-loyalty-reputation chain. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2015, 26, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MSI—Marketing Science Institute. 2020–2022 Research Priorities. Available online: https://www.msi.org/articles/2020-22-msi-research-priorities-outline-marketers-top-concerns/ (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Service-dominant logic: Continuing the evolution. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2008, 36, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D.; Andreu, L.; Gnoth, J. The dark side of the sharing economy: Balancing value co-creation and value co-destruction. Psychol. Mark. 2020, 37, 689–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busser, J.A.; Shulga, L.V. Co-created value: Multidimensional scale and nomological network. Tour. Manag. 2018, 65, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preziosi, M.; Tourais, P.; Acampora, A.; Videira, N.; Merli, R. The role of environmental practices and communication on guest loyalty: Examining EU-Ecolabel in Portuguese hotels. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 237, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šerić, M.; Gil-Saura, I.; Ruiz-Molina, M.E. How can integrated marketing communications and advanced technology influence the creation of customer-based brand equity? Evidence from the hospitality industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 39, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bormane, S. Integrated Marketing Communications in Sustainable Business. In International Scientific Conference: Society. Integration. Education; Rēzeknes Tehnoloģiju Akadēmija: Riga, Latvija, 2018; pp. 80–96. [Google Scholar]

- Alevizou, P.; Henninger, C.; Spinks, C. Communicating Sustainability Practices and Values: A case study approach of a micro-organization in the UK. Int. J. Bus. Glob. 2019, 22, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; McCabe, S.; Wang, Y.; Chong, A.Y.L. Evaluating user-generated content in social media: An effective approach to encourage greater pro-environmental behaviour in tourism? J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 600–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, M.M. Gender differences in Egyptian consumers’ green purchase behaviour: The effects of environmental knowledge, concern, and attitude. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2007, 31, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martínez, P. Customer loyalty: Exploring its antecedents from a green marketing perspective. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 896–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Xue, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, J. Green image and consumers’ word-of-mouth intention in the green hotel industry: The moderating effect of Millennials. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 181, 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moise, M.S.; Gil-Saura, I.; Ruiz Molina, M.E. The importance of green practices for hotel guests: Does gender matter? Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraž. 2021, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, P.; Rodriguez Del Bosque, I. CSR and customer loyalty: The roles of trust, customer identification with the company and satisfaction. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 35, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, V.K.; Chandra, B.; Kumar, S. Values and ascribed responsibility to predict consumers’ attitude and concern towards green hotel visit intention. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 96, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, M.T.; Aknin, L.B.; Axsen, J.; Shwom, R.L. Unpacking the Relationships Between Pro-environmental Behavior, Life Satisfaction, and Perceived Ecological Threat. Ecol. Econom. 2018, 143, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, L.C.; Coudounaris, D.N.; Kvasova, O.; Christodoulides, P. Drivers and outcomes of green tourist attitudes and behavior: Sociodemographic moderating effects. Psychol. Mark. 2015, 32, 635–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Vazquez, M.Á.; Revilla-Camacho, M.J.; Cossío-Silva, F. The value co-creation process as a determinant of customer satisfaction. Manag. Decis. 2013, 51, 1945–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallarza-Granizo, M.G.; Ruiz-Molina, M.E.; Schlosser, C. Customer value in Quick-Service Restaurants: A cross-cultural study. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 85, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merli, R.; Preziosi, M.; Acampora, A.; Ali, F. Why should hotels go green? Insights from guests experience in green hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 81, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trespalacios, J.A.; Vázquez, R.; Bello, L. Investigación de Mercados; Thomson: Madrid, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D.H.; Park, C.W. Conceptualization and measurement of multidimensionality of integrated marketing communications. J. Advert. Res. 2007, 47, 222–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.; Soutar, G.N. Value, Satisfaction and Behavioural Intentions in an Adventure Tourism Context. Ann. Tour. Res. 2009, 36, 413–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, B.; Donthu, N. Developing and validating a multidimensional consumer-based brand equity scale. J. Bus. Res. 2001, 52, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, Y.; Kim, J. Effects of brand personality on brand trust and brand affect. Psychol. Mark. 2010, 27, 639–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.; Newsted, P.R. Structural equation modeling analysis with small samples using partial least squares. In Statistical Strategies for Small Sample Research; Hoyle, R.H., Ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1999; pp. 307–341. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM); Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modelling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Validity. Psychom. Theory 1994, 3, 99–132. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, R.F.; Miller, N.B. A Primer for Soft Modelling; The University of Akron: Akron, OH, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modelling. In Modern Methods for Business Research; Marcoulides, G.A., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998; pp. 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cerri, J.; Testa, F.; Rizzi, F. The more I care, the less I will listen to you: How information, environmental concern and ethical production influence consumers’ attitudes and the purchasing of sustainable products. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 175, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).