Small Towns Recovery and Valorisation. An Innovative Protocol to Evaluate the Efficacy of Project Initiatives

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Aim of the Paper

3. Materials and Methods

- Breaking down decision problems according to a multi-level organisation (goal, criteria, sub-criteria, possible alternatives);

- Comparing quantitative and qualitative data;

- Managing and evaluating criteria, sub-criteria, and indicators;

4. Interventions for the Recovery and Valorisation of Small Towns. An Innovative Evaluation Protocol

4.1. The Evaluation Criteria

- Social criteria,

- Economic criteria,

- Environmental criteria,

- Historic-architectural criteria.

4.2. The Small Town’s Invariants

- Presence of local traditions and identities;

- Lack of services;

- Presence of typical productive activities;

- Distance from the major cities;

- Lack of adequate infrastructure;

- Environmental quality;

- Insertion in a natural context;

- Limited and compact extension of the built fabric;

- ‘Human scale’ dimension of the built fabric;

- Quality of the built heritage;

- Site-specific typological-constructive characters.

4.3. The Sub-Criteria

4.4. New Datasets of Evaluation Indicators

- Focus, in order to identify those indices that exclusively measure what you need to measure;

- Relevance, in relation to the ongoing research;

- Accessibility, with regard to the facility to access the requested data;

- Clarity, as it is necessary to adopt clear indices, the measurement of which does not allow ambiguities of interpretation;

- Frequency, so as to favour those indicators that recur most frequently within the examined panels.

4.5. The Assignment of Weights

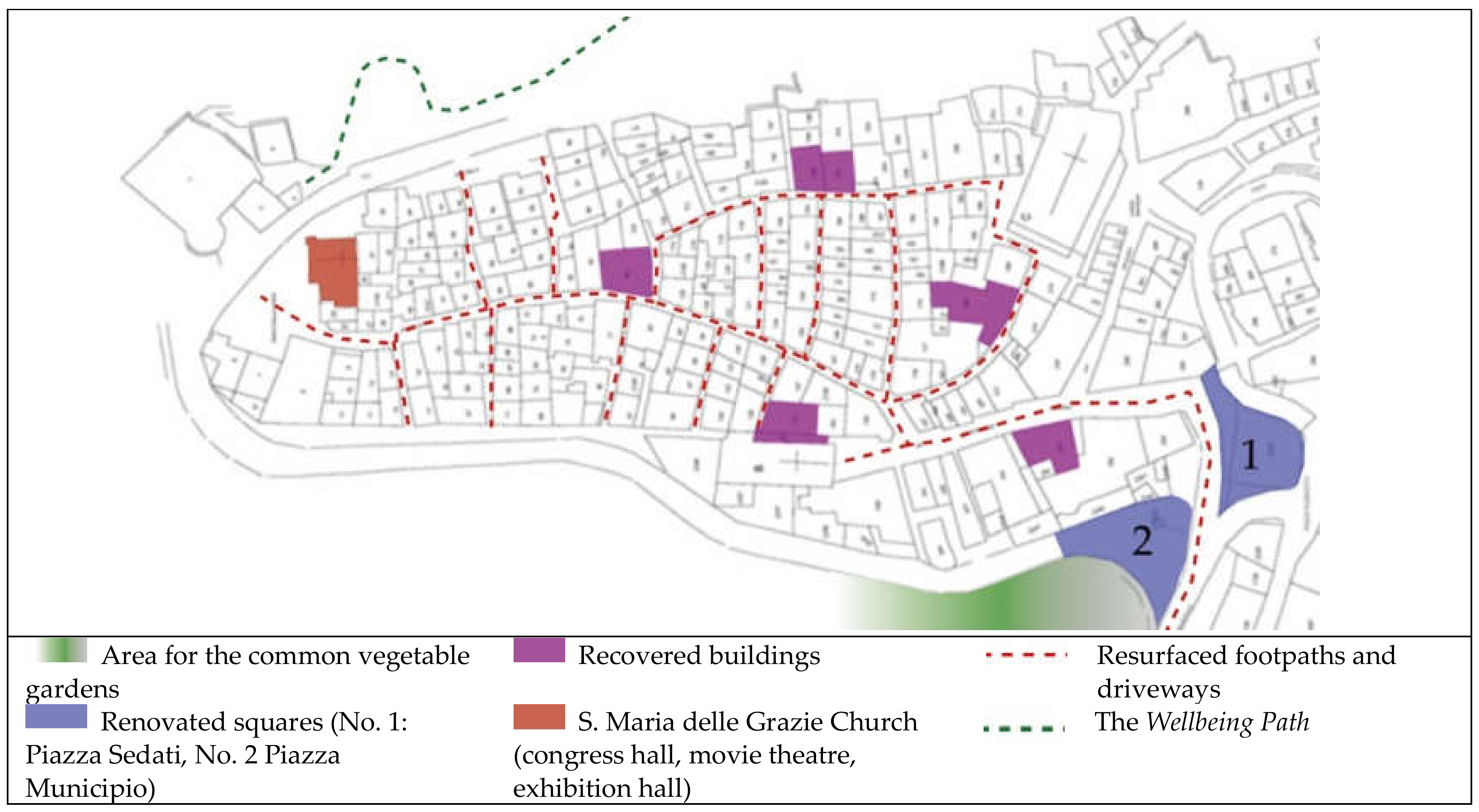

5. The Case Study

- With reference to the social criteria, in Riccia, traditions and secondary urbanisation works (schools, health centers, theatres, libraries, sports facilities, etc.) are more important (0.40) than assistance services for foreigners (0.20);

- According to the economic criteria, infrastructures (roads, public lighting, water, gas, electricity, sewage, broadband, etc.) and the productive vocations of the place (tourism, agriculture, livestock farming, crafts, etc.) are equally important;

- Under the environmental criteria, there is a higher incidence of both the bioclimatic quality of buildings (0.39) and the quality of water, air, and soil (0.32). The characteristics of flora and fauna as well as the state of preservation of green areas are of the same relevance (0.145).

- If Sw ≥ 0.6 Smax, the project is effective in achieving the goals of the sub-criteria (accepted);

- If Sw < 0.6 Smax, the project does not achieve the goals (not accepted).

SSkills recovery = 1.

6. Results Analysis

- Social criteria. The Riccia’s Well-being Village project was accepted with regard to all the three assessment social sub-criteria. The project succeeded in valorising Local traditions and identities, effectively acting on Secondary urbanisation works and Social assistance service. Table A15 gives percentage values of Sw compared to Smax above the 60% threshold for all the evaluation indexes. Specifically: Sw = 80%∙Smax for Local traditions and identities; Sw = 80%∙Smax for Secondary urbanization works; Sw = 100%∙Smax for Social assistance service.

- Economic criteria. The project was accepted with respect to the sub-criteria Primary urbanization works, while for the Productive vocations component it did not reach the required sufficiency. Table A16 shows the percentage values of Sw compared to Smax for both the sub-criteria: Sw = 100%∙Smax for Primary urbanization works; Sw = 50%∙Smax for Productive vocations. Thus, the model identified Productive vocations as a critical issue in the Well-being Village strategy. This means that the recovery and valorisation actions did not effectively look at the territory’s traditional productive activities.

- Environmental criteria. Here all the assessment sub-criteria were accepted. The Well-being Village project paid particular attention to the Flora and fauna, Environmental quality, Green areas, and Bioclimatic quality components, recording the highest percentage values: Sw = 100%∙Smax (Table A17).

- Historic-architectural criteria. The project was accepted with reference to the sub-criteria Integration with the natural environment, Visual image, Dialogue between the historic urban fabric and its context, Empty/Full relationship and equipped green space system and Formal relationship between building and urban core. In fact, as shown in Table A18, the percentage values of Sw were respectively: Sw = 100%∙Smax; Sw = 80.72%∙Smax; Sw = 100%∙Smax; Sw = 90.36%∙Smax; Sw = 100%∙Smax. On the contrary, the Typological-distributive and formal characteristics of the building recorded the percentage Sw = 50.60%∙Smax. It follows that the 60% threshold was not satisfied for this sub-criteria. This underlines the inadequacy of the project actions with regard to the fruition of the recovered architectural heritage.

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Criteria | Invariant | Sub-Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Social | Presence of local traditions and identities | Local traditions and identities |

| Lack of services | Secondary urbanization works | |

| Social assistance services | ||

| Economic | Presence of typical productive activities | Productive vocations |

| Distance from the major cities | Primary urbanization works | |

| Lack of adequate infrastructure | ||

| Environmental | Environmental quality | Flora and fauna |

| Environmental quality (water, air, soil) | ||

| Green areas | ||

| Bioclimatic quality | ||

| Historic-architectural | Insertion in a natural context | Integration with the natural environment |

| Visual image (evocative force) | ||

| Limited and compact extension of the built fabric | Dialogue between the historic urban fabric and its context | |

| ‘Human scale’ dimension of the built fabric | Full/empty relationship and equipped green space system | |

| Quality of the built heritage | Formal relationship between building and urban core | |

| Site-specific typological-constructive characters | Typological-distributive and formal characteristics of the building |

| Goal | Small Towns Valorization | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria | Social | Economic | Environmental | Historical-architectural |

| Sub-criteria | Local traditions and identities Secondary urbanization works (kindergartens, schools, health facilities) Social assistance services (services for the elderly, for disabled people, for immigrants) | Productive vocations (agriculture, crafts, industry, commerce, tourism) Primary urbanization works (roads, parking lots, electricity network, teleph. network, gas network, public lighting, water network) | Territory | Territory |

| Flora and fauna Environmental quality (water, air, soil) | Integration with the natural environment | |||

| Urban core | Urban core | |||

| Green areas | Visual image Dialogue between the historic urban fabric and its context Full/empty relationship and equipped green space system | |||

| Building | Building | |||

| Bioclimatic quality | Formal relationship between building and urban core Typological-distributive and formal characteristics of the building | |||

| Author(s) | Year | Title | N. Indicators |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mega V., Pedersen J. | 1998 | Urban Sustainability Indicators | 16 |

| European Commission | 2008 | European Green Capital Award | 12 |

| Mameli F., Marletto G. | 2009 | A selection of indicators for monitoring sustainable urban mobility policies | 14 |

| Vallega A. | 2009 | Indicatori per il paesaggio | 37 |

| European Environment Agency | 2010 | EEA Urban Metabolism Framework | 15 |

| United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) | 2011 | Transport for sustainable development in the ECE region | 17 |

| Volpiano M. | 2011 | Indicators for the Assessment of Historic Landscape Features | 12 |

| Swiss Confederation | 2012 | Ufficio Federale dell’Ambiente UFAM – Paesaggio: Indicatori | 11 |

| EU Commission, Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development | 2013 | Rural Development in the European Union - Statistical and Economic Information, Report 2013 | 59 |

| European Spatial Planning Observation Network | 2013 | KITCASP - Key Indicatorsfor Territorial Cohesion and Spatial Planning | 20 |

| Phillips R. G., Stein J. M. | 2013 | An Indicator Framework for Linking Historic Preservation and Community Economic Development | 29 |

| Valtenbergs V., González A., Piziks R. | 2013 | Selecting indicators for sustainabledevelopment of small towns: the case of Valmiera municipality | 73 |

| European Environment Agency | 2014 | Digest of EEA Indicators 2014 - Core Set of Indicators (CSI) | 42 |

| UN-Habitat - United Nations Human Settlements Programme | 2016 | MEASUREMENT OF CITY PROSPERITY - Methodology and Metadata | 39 |

| Bosch P., Jongeneel S., Rovers V., Neumann H-M., Airaksinen M., Huovila A. | 2017 | CITYkeys list of city indicators | 74 |

| TOT. | 470 |

| SOCIAL CRITERIA | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sub-Criteria | Indicator | Description | |

| Local traditions and identities | Indicated by literature | Sense of place/identification with place/attachement to place | The way people perceive the resources and historical environment of their community. There is an identity linked to the place that evokes a special sense of place. This indicator requires a direct survey among the inhabitants of the historical sites. |

| The number of cultural events | n. of cultural events. Did the implemented strategy safeguard and/or support cultural events? YES/NO. | ||

| The number of visitors in cultural events | n. visitors in cultural events. | ||

| Taste’s places | It is evaluated by the level at which the “taste’s places” enter into landscape valorization policies Gc expresses the number of “taste’s places” subject to interventions and measures included in the territorial plans, aimed at enhancing their value in relation to the landscape. Gt expresses the total number of “taste’s places” existing in the considered territory. | ||

| Event places | It is assessed by the degree to which “event places” are included in the perception of the landscape and are enhanced through ad hoc measures Ec expresses the number of “event places” subject to interventions and measures included in the territorial plans, aimed at enhancing their value in relation to the landscape.Et expresses the total number of “event places” existing in the considered territory. | ||

| Proposed | Number of traditions (fables, historical events, music) / religious traditions / gastronomic traditions / festivals, exhibitions and markets | n. of oral, religious, gastronomic traditions, festivals, fairs, and markets. Has the implemented strategy safeguarded and/or supported local traditions? YES/NO. | |

| Secondary urbanization works | Land Use Mix | Land use diversity per square kilometre, within a city or urban area (residential, commercial, and services, industrial, public facilities, and public spaces). | |

| Land use change | % of total (building, roads, domestic, green space, agricultural, woodland, water, etc.). | ||

| Access to services (hospitals and schools) | Travel time (minutes) to hospitals/schools. | ||

| Access to basic health care services | % of people. | ||

| Access to local/neighbourhood services within a short distance | Not specified in the bibliographical reference. It is proposed the distance in km to reach the nearest services. | ||

| Unemployment structure | Not specified in the bibliographical reference. It is proposed the % of unemployed residents. | ||

| Social Justice Indicator | Percentage of the population affected by poverty, unemployment, lack of access to education, information, training, and leisure. | ||

| Development of service sector | This indicator measures the share of Gross Value Added (GVA) in the services sector in a region. | ||

| Access to public amenities | % of people | ||

| Access to commercial amenities | % of people | ||

| Access to educational resources | Likert’s scale. Wherever possible, the use of the percentage of the population accessing educational resources is suggested. | ||

| Number of public libraries | Number of public libraries per 100,000 people (n./100,000 people) or No. public libraries/Total libraries. Did the strategy include new public bookshops/libraries? YES/NO. | ||

| Indicated by literature | The number of assistance centers | n. of assistance centers. | |

| Net migration | It’s the ratio of net migration during the year to the average population in that year. It is also possible to use: n./1000. | ||

| Average number of assistance hours per year | Average number of assistance hours per year. | ||

| Percentage difference between the offered services level and the standard services level | Percentage difference between the offered services level and the standard services level. | ||

| Quantitative level of benefits | To be estimated on the most appropriate evaluation scale, depending on the available information framework. | ||

| Proposed | Percentage of those who benefit from social assistance services on the resident population | % of population benefiting from social assistance services/total resident population. | |

| ECONOMIC CRITERIA | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sub-criteria | Indicator | Description | |

| Productive vocations | Indicated by literature | Forest areas extensively exploited | Not specified in the bibliographical reference. It is proposed the surface in m2 of extensively exploited forest areas. |

| Agricultural areas | Not specified in the bibliographical reference. It is proposed the surface in km2 of agricultural areas. | ||

| Economic specialization | Shows the level (high or low) through which a city focuses its economic activities on certain goods and services Si2 is the employment share in the city’s industry. This share is expressed with a number and not a percentage. N is the total number of industries. H varies from 1/N to 1. A value of H greater than 0,25 indicates a high concentration. | ||

| Structure of the economy | % GVA by branch (primary/secondary/tertiary sector. | ||

| Land use efficiency | Not specified in the bibliographical reference. It is proposed to make use of expert judgements, from which a quantitative evaluation algorithm can be deduced. | ||

| Distribution of businesses and employed by industries | Not specified in the bibliographical reference. It is proposed the number of employees in the industrial sector. | ||

| The number of tourists | Not specified in the bibliographical reference. It is proposed the number of tourists per year. | ||

| Foreign Direct Investments | Capital/Earnings. | ||

| Accomodation load | Not specified in the bibliographical reference. It is proposed the accommodation capacity of the structures (hotels, hostels, b&b, etc.) as number of beds. | ||

| Dynamics of foundation and dissolution of local businesses | Not specified in the bibliographical reference. An economic indicator is proposed, depending on the level of information available. | ||

| The number of guest nights | Number of guest nights. | ||

| Economic enhancement of historical-cultural heritage networking | It is proposed to evaluate this parameter according to the specificities of the case study. | ||

| Agricultural land use | % of Utilised Agricultural Area (UAA) in arable land/permanent pasture/permanent crops. | ||

| Economic development of non-agricultural sector | GVA (million EUR) in secondary and tertiary sectors. | ||

| Tourism infrastructure in rural areas | Total number of bed places in tourist accommodations (%). | ||

| Tourism intensity | n./100.000. | ||

| Local food production | % of tonnes. | ||

| Green jobs | % of jobs. | ||

| Land use change | % of total (building, roads, domestic, green space, agricultural, woodland, water, etc.). | ||

| Skills recovery | Has the strategy promoted the recovery of local skills? YES/NO. | ||

| Real estate value increase | % increase in real estate value driven by strategy. | ||

| Prevailing cultivation | % of cultivations. | ||

| Primary urbanization works | Indicated by literature | Length of mass transport network | Km/1,000,000 people |

| Length of bike route network | % in km | ||

| Public transport network length | Not specified in the bibliographical reference. It is proposed the route length in km (tram, trolleybus, bus). | ||

| Street intersection density | Number of street intersections per one square kilometer of urban area (n./km2). | ||

| Street density | Number of kilometers of urban streets per square kilometer of land (km/km2). | ||

| Infrastructure density | km of roads per 1,000 inhabitants. | ||

| Infrastructure quality | Not specified in the bibliographical reference. It is proposed the % of road surface that is asphalted or in good condition (no holes, cracks, depressions, spalling, bulges) over the total existing road surface. | ||

| Percentage of houses with communications (including electricity, water, sewage, gas, heating, internet, phone lines) | % of houses equipped with electrical system, water system, purification system, gas, heating, internet, telephone line. | ||

| The number of public Wi-Fi places | Number of public spaces equipped with Wi-Fi. | ||

| Public and private services accessibile via telephone and computer | Not specified in the bibliographical reference. The indicator should be chosen according to the data availability. | ||

| Transportation mode split (percentage of each mode of transportation, i.e. private, public, bicycles, pedestrians) | % of each transport mode (public, private, cycle, walking). | ||

| Internet access | It is the ratio between the total number of Internet users in a city and the total population of the same city (%). | ||

| Home computer access | Percentage of families owning household computers compared to the total number of families in the city (%). | ||

| Internet infrastructure | Families with DSL coverage (%). | ||

| Internet take-up in rural areas | Families with a broadband connection contract (% of families with at least one member aged between 16 and 74 years). | ||

| Access to electricity | Percentage of families connected to the national network. | ||

| Access to public transport | % of people | ||

| Access to high speed internet | # (n.)/100 | ||

| Access to public free WiFi | % of m2 | ||

| Public transport use | # (n.)/cap/year | ||

| Land occupied by transport infrastructures | Not specified in the bibliographical reference. A percentage evaluation is proposed. | ||

| Quality of the street and sidewalks cover | Not specified in the bibliographical reference. It is proposed the use of expert judgements (scoring scale). | ||

| Proposed | % of public transport | % | |

| Sewerage meters in good condition | Did the strategy include the replacement of degraded sewer sections? YES/NO. | ||

| ENVIRONMENTAL CRITERIA | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sub-Criteria | Indicator | Description | |

| Territory | |||

| Flora and fauna | Land cover | % area in agricultural/forest/natural classes. | |

| Protected forest | Not specified in the bibliographical reference. It is proposed an evaluation based on the extension in m2. | ||

| The number of protected animal and plant species | n. of protected animal and plant species. | ||

| Percentage of preserved area/reservoirs/waterways/parks in relation to total land area | % areas, reserves, rivers, protected parks in relation to the total territorial area. | ||

| Species and habitats of European interest | Not specified in the bibliographical reference. It is proposed the use of a numerical or percentage data. | ||

| Number and status of protected European habitats and species | Number and Conservation Status (EU defined status of Natura 2000 sites—SACs and SPAs and Annexed species). | ||

| Designated areas | km2, %, number of species and habitats listed by the Habitats Directive. | ||

| Land take | Hectares or km2 | ||

| Urban land take | % of land that is converted from natural and semi-natural areas (including wooded and agricultural areas) to artificial land used for urban and economic purposes. | ||

| Proportion of protected areas | Not specified in the bibliographical reference. It is proposed the % of protected natural areas on the total number of existing natural areas. | ||

| Biodiversity: Tree species composition | Area of forest classified by number of tree species occurring and by forest type (%). | ||

| Biodiversity: Protected forest | _ Share of FOWL protected under MCPFE classes (%) _ Change of FOWL area protected under MCPFE classes (ha) | ||

| Forest ecosystem health | % of sampled trees in defoliation classes 2–4 (all trees/conifers/broadleaves). | ||

| Protected areas and elements | Surface extension. Level of environmental protection. Number of protected elements. Other specific indicators. | ||

| Ecologically protected areas | % of surface area subject to ecological protection measures in relation to the total surface area Sp is the area in hectares (ha) subject to protection measures. St is the total area, expressed in hectares (ha), of the considered territory. | ||

| Protected species | % of protected plant and/or animal species in relation to all existing plant and/or animal species Sp is the number of species, belonging to the wild vegetation, subject to protective measures. St is the number of species, belonging to spontaneous vegetation, existing at the time the survey is carried out. | ||

| Environmental quality (water, air, soil) | Indicated by literature | Renewable energy production (wind, hydro, biomass, etc.) | Megawatts and % by renewable energy type. |

| Greenhouse gas emissions | Tonnes CO2 eq. per individual. | ||

| Water quality | Specific quality indicator. | ||

| Water quality status | Absolute values on the actual status or objective met/failed (as per WFD for groundwater, rivers, lakes, estauarine, coastal). | ||

| Air quality | Specific quality indicator. | ||

| Emissions of main air pollutants | Specific indicator. | ||

| Exposure of ecosystems to acidification, eutrophication and ozone | Specific indicator. | ||

| Exceedance of air quality limit values in urban areas | Specific indicator. | ||

| Atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations | Specific indicator. | ||

| Green growth and eco-innovation | Specific indicator. | ||

| Global Climate Indicator (GCI) | Emitted total CO2, CH₄, N2O and CFC and halons. | ||

| CO2 emissions | Specific indicator. | ||

| Emission of greenhouse gases and local pollutants | Specific indicator. | ||

| Proposed | Presence of treatment systems | YES/NO. | |

| Urban core | |||

| Green areas | Green area per capita | Green surface per capita. | |

| Green space | Hectares/100,000 or m2 of green space per inhabitant. | ||

| Building | |||

| Bioclimatic quality | Proposed | Shape and orientation | Type of shape. Building orientation. |

| Ventilation quality | Presence/absence of internal ventilation. Ventilation level. | ||

| Energy class | Level. | ||

| Use of photovoltaic or solar panels | YES/NO. | ||

| HISTORIC-ARCHITECTURAL CRITERIA | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sub-Criteria | Indicator | Description | |

| Territory | |||

| Integration with the natural environment | Indicated by literature | Exceptionality of the historical-cultural characteristics of the landscape | Score scale. |

| Fragility of the historical-cultural characteristics of the landscape | Score scale. | ||

| Designation of rural areas | «[…] If more than 50% of the total population lives in rural grid cells, the region is classified as predominantly rural. Regions where between 20% and 50% of the population lives in rural grid cells are considered intermediate, while those with less than 20% in rural grid cells are predominantly urban» | ||

| Importance of rural areas | This indicator consists in 4 sub-indicators:

| ||

| Protected areas and elements | Surface extension. Level of environmental protection. Number of protected elements. Other specific indicators. | ||

| Settlement dispersion | Urban penetration units per km2 of landscape (DSE/km2) Alternatively, it can be replaced with an urban sprawl index i refers to an urban area. t refers to the initial year of investigation and t+n to the final year. urb refers to the built area (in terms of land consumed) expressed in km2 within administrative boundaries. pop is the total population of the municipality. | ||

| Landscape value of skyline | Visual and aesthetic impact produced by human presence and activities on the skyline (linear/areal impact coefficient) Li expresses the overall length of the lines drawn by human works (roads, railways, and so on) engraved on the skyline, measured on the outline of the territory that appears from the photographic vision and/or cartographic representation. Lb expresses the baseline length delimited by that portion of the skyline. Si expresses the total surface area of the area engravings produced by human communities on the outline delimited by the skyline. Sc expresses the surface area limited by the skyline. | ||

| Injured landscape | Representative indices of human impact on the landscape Af represents the sum of the surface area, measured in hectares (ha), of areas occupied by landfills and quarries, as well as areas degraded due to hydrogeological instability. At represents the total suburban area of the considered territory. | ||

| Proposed | Landscape infrastructures (religious itineraries, transhumance routes, protoindustrial architecture paths) | km of paths and trails recovered and/or valorized. | |

| Urban core | |||

| Visual image (evocative force) | Indicated by literature | Historic preservation element/plan and integration with community planning | It is important to note if the local government has or does not have a historic preservation plan as part of its overall plan (the community masterplan). |

| Fragility of the historical-cultural characteristics of the landscape | Score scale. | ||

| Significance/Typicality of the historical-cultural characteristics of the landscape | Score scale. | ||

| Landscape perceived beauty | Average score given through questionnaires on the beauty of the landscape in a specific municipality (1 = not corresponding at all; 5 = corresponding in full). | ||

| Landscape value of skyline | Visual and aesthetic impact produced by human presence and activities on the skyline (linear/areal impact coefficient) Li expresses the overall length of the lines drawn by human works (roads, railways, etc.) engraved on the skyline, measured on the outline of the territory that appears from the photographic vision and/or cartographic representation. Lb expresses the baseline length delimited by that portion of the skyline. Si expresses the total surface area of the area engravings produced by human communities on the outline delimited by the skyline. Sc expresses the surface area limited by the skyline. | ||

| Panoramic sites | Relevance of panoramic sites in the perception of the landscape and in the preservation of its quality Pb indicates the number of panoramic sites that can offer views of the surrounding landscape. Pd indicates the number of panoramic sites that have deteriorated as a result of improper interventions on the territory. | ||

| Parking pressure | Visual impact dimension of car parks on the landscape Lp expresses the length, calculated in km, of linear developments which, at times of maximum frequency, are assumed by vehicles aligned along lines relevant from the landscape point of view. Lc expresses the length, calculated in km, of the relevant country lines developing in the territory concerned. Sp expresses the surface area, calculated in hectares (ha) of the spaces that, at times of maximum frequency, are car parks within the territory considered. Sc expresses the surface area, calculated in hectares (ha), of the territory characterized by the landscape to be safeguarded. | ||

| Proposed | Visual interference (or the presence of illegal building and/or architectural artefacts out of scale with respect to the pre-existing built fabric) | m3 of illegal building and/or architectural artefacts out of scale with respect to the pre-existing built fabric. | |

| Hydrographic ponds | N. of existing or designed hydrographic elements (natural or artificial). | ||

| Dialogue between the historic urban fabric and its context | Indicated by literature | Perceived quality of the landscape around the own home | Share of interviewees who were “not at all satisfied” (0) to “very satisfied” (5) with the quality of the landscape around their home. |

| Panoramic sites | Relevance of panoramic sites in the perception of the landscape and in the preservation of its quality Pb indicates the number of panoramic sites that can offer views of the surrounding landscape. Pd indicates the number of panoramic sites that have deteriorated as a result of improper interventions on the territory. | ||

| Proposed | Urban morphology (intended as the aggregation mode of settlements that define their form. The elements that structure an urban core are considered: streets, buildings, open spaces, green areas) | How much the project proposal alters the way the settlement is aggregated (score scale). | |

| Level of the relationship between the small town and its context | Score scale. | ||

| Full/empty relationship and equipped green space system | Preservation of relation systems between assets | Score scale. | |

| Accessibility to open public areas | Percentage (%) of urban area that is located less than 400 m away from an open public space | ||

| Green, Public space and Heritage Indicator (GPI) | Percentage of green or public spaces and local heritage to be enhanced. | ||

| Public outdoor recreation space | m2/cap | ||

| Green space accessibility | % of total population within 500 metres of public managed green areas (active and passive). | ||

| The number of green space reconstruction projects | No. of green space reconstruction projects. YES= score 5; NO= score 0. | ||

| Urban pedestrian areas | Urban surface area pedestrianized in relation to the quality of the landscape Pe indicates the extension, measured in hectares (ha), of existing pedestrian spaces. S indicates the extension, measured in hectares (ha), of the total urban area. | ||

| Valuing of urban public parks and gardens | It provides an evaluation of the green spaces’ function within the urban landscape Sa indicates the area, measured in hectares (ha), of existing green spaces in the urban environment at the present time. Sn indicates the area, measured in hectares (ha), of the green spaces that should be realised. | ||

| Revitalization of historical urban spaces | Relationship between the urban spaces that have benefited, or are benefiting, from architectural recovery and cultural valorization in a single city, or in a complex of cities, and the complex of historical urban spaces existing in the urban context considered SR expresses the surface area, measured in hectares (ha), of the city’s historical spaces that have benefited from architectural restoration and cultural heritage valorization. Sr expresses the surface area, measured in hectares (ha), of historical spaces which, at the time the indicator is calculated, are subject to architectural restoration and cultural valorization. St expresses the total area, measured in hectares (ha), of the city’s historical spaces taken into account. | ||

| Building | |||

| Formal relationship between building and urban core | State of preservation of built heritage with reference to characterizing elements | Score scale. | |

| Historic preservation element/plan and integration with community planning | It is important to note if the local government has or does not have a historic preservation plan as part of its overall plan (the community masterplan). | ||

| Historic fabric | Measures the amount (%) of historical fabric in a specific community. This is done by dating the structures from the foundation of the settlement to the present day. | ||

| Typological-distributive and formal characteristics of the building | Preservation of the assets | It is proposed to evaluate this parameter according to the specificities of the case study (score scale). | |

| Use of historical-cultural heritage | Percentage of buildings in use. | ||

| Preservation of cultural heritage | Likert’s scale. | ||

| Ground floor usage | % of m2 | ||

| SUB-CRITERIA | ||||||

| Local traditions and identities | Secondary urbanization works | Social assistance service | Sub-criteria weights | % | ||

| SUB-CRITERIA | Local traditions and identities | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 40% |

| Secondary urbanization works | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 40% | |

| Social assistance service | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 20% | |

| SUB-CRITERIA | |||||

| Productive vocations | Primary urbanization works | Sub-criteria weights | % | ||

| SUB-CRITERIA | Productive vocations | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 50% |

| Primary urbanization works | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 50% | |

| SUB-CRITERIA | |||||||

| Flora and fauna | Environmental quality | Green areas | Bioclimatic quality | Sub-criteria weights | % | ||

| SUB-CRITERIA | Flora and fauna | 0.14 | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.145 | 14.5% |

| Environmental quality | 0.28 | 0.33 | 0.28 | 0.37 | 0.32 | 32% | |

| Green areas | 0.14 | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.145 | 14.5% | |

| Bioclimatic quality | 0.43 | 0.33 | 0.43 | 0.37 | 0.39 | 39% | |

| SOCIAL CRITERIA | |

|---|---|

| SUB-CRITERIA | SELECTED INDICATOR(S) |

| Local traditions and identities |

|

| Secondary urbanization works |

|

| Social assistance service |

|

| ECONOMIC CRITERIA | |

|---|---|

| SUB-CRITERIA | SELECTED INDICATOR(S) |

| Productive vocations |

|

| Primary urbanization works |

|

| ENVIRONMENTAL CRITERIA | |

|---|---|

| SUB-CRITERIA | SELECTED INDICATOR(S) |

| Flora and fauna |

|

| Environmental quality |

|

| Green areas |

|

| Bioclimatic quality |

|

| HISTORIC-ARCHITECTURAL CRITERIA | |

|---|---|

| SUB-CRITERIA | SELECTED INDICATOR(S) |

| Integration with the natural environment |

|

| Visual image |

|

| Dialogue between the historic urban fabric and its context |

|

| Empty/Full relationship and equipped green space system |

|

| Formal relationship between building and urban core |

|

| Typological-distributive and formal characteristics of the building |

|

| Sub-Criteria | Weight (W) | Assessment Indicator | Score (S) | Weighted Score (Sw) | Maximum Weighted Score (Smax) | % Sw Compared to Smax |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local traditions and identities | 40% |

| 4 | 1.6 | 2 | 80% > 60% ACCEPTED |

| Secondary urbanization works | 40% |

| 4 | 1.6 | 2 | 80% > 60% ACCEPTED |

| Social assistance service | 20% |

| 5 | 1 | 1 | 100% > 60% ACCEPTED |

| Sub-Criteria | Weight (W) | Assessment Indicator | Score (S) | Weighted Score (Sw) | Maximum Weighted Score (Smax) | % Sw Compared to Smax |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Productive vocations | 50% |

| 4 | 1.25 | 2.5 | 50% < 60% NOT ACCEPTED |

| 1 | |||||

| Primary urbanization works | 50% |

| 5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 100% > 60% ACCEPTED |

| 5 | |||||

| 5 |

| Sub-Criteria | Weight (W) | Assessment Indicator | Score (S) | Weighted Score (Sw) | Maximum Weighted Score (Smax) | % Sw Compared to Smax |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Territory | ||||||

| Flora and fauna | 14.5% |

| 5 | 0.725 | 0.725 | 100% > 60% ACCEPTED |

| Environmental quality | 32% |

| 5 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 100% > 60% ACCEPTED |

| 5 | |||||

| Urban core | ||||||

| Green areas | 14.5% |

| 5 | 0.725 | 0.725 | 100% > 60% ACCEPTED |

| Building | ||||||

| Bioclimatic quality | 39% |

| 5 | 1.95 | 1.95 | 100% > 60% ACCEPTED |

| Sub-Criteria | Weight (W) | Assessment Indicator | Score (S) | Weighted Score (Sw) | Maximum Weighted Score (Smax) | % Sw Compared to Smax |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Territory | ||||||

| Integration with the natural environment | 16.66% |

| 5 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 100% > 60% ACCEPTED |

| Urban core | ||||||

| Visual image | 16.66% |

| 4 | 0.67 | 0.83 | 80.72% > 60% ACCEPTED |

| Dialogue between the historic urban fabric and its context | 16.66% |

| 5 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 100% > 60% ACCEPTED |

| Empty/Full relationship and equipped green space system | 16.66% |

| 5 | 0.75 | 0.83 | 90.36% > 60% ACCEPTED |

| 4 | |||||

| Building | ||||||

| Formal relationship between building and urban core | 16.66% |

| 5 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 100% > 60% ACCEPTED |

| Typological-distributive and formal characteristics of the building | 16.66% |

| 4 | 0.42 | 0.83 | 50.60% < 60% NOT ACCEPTED |

| 1 | |||||

References

- Nesticò, A.; D’Andria, E.; Fiore, P. Centri Minori e Strategie di Intervento. In I Centri Minori da Problema a Risorsa. Strategie Sostenibili per la Valorizzazione del Patrimonio Edilizio, Paesaggistico e Culturale Nelle Aree Interne, 1st ed.; Fiore, P., D’Andria, E., Eds.; FrancoAngeli Editore: Milan, Italy, 2019; p. 1399. [Google Scholar]

- De Rossi, A. (Ed.) Riabitare l’Italia. Le Aree Interne tra Abbadoni e Riconquiste, 1st ed.; Donzelli Editore: Rome, Italy, 2018; p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Visvizi, A.; Lytras, M.; Mudri, G. Smart Villages in the EU and Beyond, 1st ed.; Emerald Group Pub Ltd: Bingley, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Patnaik, S.; Sen, S.; Mahmoud, M. (Eds.) Smart Village Technology, 1st ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fiore, P.; Blandón-González, B.; D’Andria, E. Smart Villages for the Sustainable Regeneration of Small Municipalities. In Modernization and Globalization: Challenges and Opportunities in Architecture, Urbanism, Cultural Heritage, 1st ed.; Nepravishta, F., Maliqari, A., Eds.; Flesh: Tiranë, Albania, 2019; pp. 840–847. [Google Scholar]

- Servillo, L.; Atkinson, R.; Smith, I.; Russo, A.; Sýkora, L.; Demazière, C.; Hamdouche, A. Town, Small and Medium Sized Towns in Their Functional Territorial Context, 1st ed.; Draft Final Report; Espon: Luxembourg, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Copus, A.; Kahila, P.; Fritsch, M.; Dax, T.; Kovács, K.; Tagai, G.; Weber, R.; Grunfelfer, J.; Löfving, L.; Moodie, J.; et al. Escape European Shrinking Rural Areas: Challenges, Actions and Perspectives for Territorial Governance, 1st ed.; Final Report; Espon: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum, J.; Fox, L.; Hawken, P. Sustainable Revolution: Permaculture in Ecovillages, Urban Farms, and Communities Worldwide, 1st ed.; North Atlantic Books: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Litfin, K. Ecovillages: Lessons for Sustainable Community, 1st ed.; Polity Pr: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Guidotti, F. Ecovillaggi e Cohousing, 1st ed.; Terra Nuova Edizioni: Florence, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- ANCE. I Borghi d’Italia Dalla Visione Alla Rigenerazione, 1st ed.; ANCE: Rome, Italy, 2017; p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Del Molino, S. La Spagna Vuota, 1st ed.; Sellerio Editore: Palermo, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Paolella, A. Il Riuso dei Borghi Abbandonati. Esperienze di Comunità, 1st ed.; Pellegrini Editore: Cosenza, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Berizzi, C.; Rocchelli, L. Borghi Rinati. Paesaggi Abbandonati e Interventi di Rigenerazione, 1st ed.; Il Poligrafo: Padua, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ricci, M.; Battisti, A.; Monardo, B. (Eds.) I Borghi della Salute. Healthy Ageing per Nuovi Progetti di Territorio, 1st ed.; Alinea Editrice: Florence, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Droli, M.; Dall’Ara, G. Ripartire Dalla Bellezza. Gestione e Marketing Delle Opportunità D’innovazione Nell’albergo Diffuso nei Centri Storici e Nelle Aree Rurali, 1st ed.; CLEUP: Padua, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- D’Andria, E.; Fiore, P.; Nesticò, A. Historical-Architectural Components in the Projects Multi-criteria Analysis for the Valorization of Small Towns. In New Metropolitan Perspectives, 1st ed.; Bevilaqua, C., Calabrò, F., Della Spina, L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 178, pp. 652–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coletta, T. de la source I Centri Storici Minori Abbandonati Della Campania. Conservazione, Recupero e Valorizzazione; Edizioni Scientifiche Italiane: Naples, Italy, 2010; p. 77. [Google Scholar]

- Figueira, J.; Greco, S.; Ehrgott, M. Multiple Criteria Decision Analysis: State of the Art Surveys, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nesticò, A.; Somma, P. Comparative Analysis of Multi-Criteria Methods for the Enhancement of Historical Buildings. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ishizaka, A.; Nemery, P. Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis: Methods and Software, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, B. Méthodologie Multicritére d’Aide à la Décision, 1st ed.; Economica: Paris, France, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Guitoni, A.; Martel, J.M. Tentative guidelines to help choosing an appropriate MCDA method. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1998, 109, 501–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincke, P. L’aide Multicritère à la Décision, 1st ed.; Université de Bruxelles: Bruxelles, Belgium, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Colson, G.; De Bruyn, C. Models and Methods in Multiple Criteria Decision Making, 1st ed.; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1989; Volume 23. [Google Scholar]

- Fishburn, P.C. A Survey of Multiattribute/Multicriterion Evaluation Theories. In Multiple Criteria Problem Solving, 1st ed.; Zionts, S., Ed.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 1978; pp. 181–224. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, B.; Bouyssou, D. Aide Multicritère à la Décision: Methodes et Cas, 1st ed.; Economica: Paris, France, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Keeney, R.L.; Raiffa, H. Decisions with Multiple Objectives: Preferences and Value Trade-Offs, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- De Montis, A. Analisi Multicriteri e Valutazione per la Pianificazione Territoriale, 1st ed.; CUEC Editrice: Cagliari, Italy, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Mardani, A.; Jusoh, A.; Nor, K.; Khalifah, Z.; Zakwan, N.; Valipour, A. Multiple criteria decision-making techniques and their applications—A review of the literature from 2000 to 2014. Econ. Res. Ekon. Istraživanja 2015, 28, 516–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanza, A. Lo Sviluppo Sostenibile, 4th ed.; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, J.; Pekmezovic, A.; Walker, G. Sustainable Development Goals: Harnessing Business to Achieve the SDGs Through Finance, Technology and Law Reform, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Clementi, C.; Giordani, M.; Poponessi, P. L’Italia dei Borghi. Strategie di Promozione e Comunicazione, 1st ed.; Historica Edizioni: Cesena, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nesticò, A.; De Mare, G. Government Tools for Urban Regeneration: The Cities Plan in Italy. A Critical Analysis of the Results and the Proposed Alternative. In International Conference on Computational Science and Its Applications; Part II, LNCS, 2014; Murgante, B., Misra, S., Rocha, A.M.A.C., Torre, C., Rocha, J.G., Falcão, M.I., Taniar, D., Apduhan, B.O., Gervasi, O., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; Volume 8580, pp. 547–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottero, M.; Lami, I.; Lombardi, P. Analytic Network Process. La Valutazione di Scenari di Trasformazione Urbana e Territoriale, 1st ed.; Alinea Editrice: Florence, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fusco Girard, L.; Nijkamp, P. Le Valutazioni per lo Sviluppo Sostenibile Della Città e del Territorio, 3rd ed.; FrancoAngeli: Milan, Italy, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Carver, N.F. Borghi Collinari Italiani, 1st ed.; Clean Edizioni: Naples, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nesticò, A.; D’Andria, E.; Fiore, P. Small towns and valorization projects. Criteria and indicators for economic evaluation. Valori Valutazioni 2020, 25, 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Romana Stabile, F.; Zampilli, M.; Cortesi, C. Centri Storici Minori. Progetti per il Recupero Della Bellezza, 1st ed.; Gangemi: Rome, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Briatore, S. Valorizzazione dei Centri Storici Minori. Strategie di Intervento, 1st ed.; Diabasis Edizioni: Reggio Emilia, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cirasa, M. Recupero Degli Spazi Aperti di Relazione nei Centri Storici Minori. Aspetti Bioclimatici e Innovazione Tecnologica, 1st ed.; Gangemi: Rome, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fiore, P. La Valorizzazione dei Centri Minori. Strategie per una Conservazione Integrata Dell’antico Borgo di Aterrana, 1st ed.; CUES: Fisciano, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mega, V.; Pedersen, J. Urban Sustainability Indicators, 1st ed.; Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Mameli, F.; Marletto, G. A Selection of Indicators for Monitoring Sustainable Urban Mobility Policies. In Trasporti, Ambiente e Territorio. La Ricerca di un Nuovo Equlibrio, 1st ed.; Marletto, G., Musso, E., Eds.; FrancoAngeli Editore: Milan, Italy, 2010; pp. 167–174. [Google Scholar]

- Vallega, A. Indicatori per il Paesaggio, 1st ed.; FrancoAngeli: Milan, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Minx, J.; Creutzig, F.; Ziegler, T.; Owen, A. Developing a Pragmatic Approach to Assess Urban Metabolism in Europe. A Report to the European Environment Agency, 1st ed.; Technische Universität Berlin; Stockholm Environment Institute; Climatecon: Berlin, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Directorate-General Environment, European Commission. Science for Environment Policy, In-Depth Report: Indicators for Sustainable Cities; EEA Urban Metabolism Framework; Issue 12; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018; p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. Transport for Sustainable Development in the ECE Region, 1st ed.; UNECE Transport Division: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Volpiano, M. Indicators for the Assessment of Historic Landscape Features. In Landscape Indicators, 1st ed.; Cassatella, C., Peano, A., Eds.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 77–104. [Google Scholar]

- Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development. Rural Development in the European Union Statistical and Economic Information Report 2013, 1st ed.; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- European Spatial Planning Observation Network (ESPON). KITCASP. Key Indicators for Territorial Cohesion and Spatial Planning. Part A, Executive Summary, 1st ed.; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, R.G.; Stein, J.M. An Indicator Framework for Linking Historic Preservation and Community Economic Development. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 113, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valtenbergs, V.; González, A.; Piziks, R. Selecting Indicators for Sustainable Development of Small Towns: The Case of Valmiera Municipality. Procedia Comput. Sci. Spec. Issue ICTE Reg. Dev. 2013, 26, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- European Environment Agency (EEA). Core Set of Indicators (CSI). In Digest of EEA Indicators 2014, 1st ed.; European Environment Agency: Luxembourg, 2014; Volume 8, pp. 28–31. [Google Scholar]

- UN-Habitat. Measurement of City Prosperity. Methodology and Metadata, 1st ed.; UN-Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2016; pp. 20–128. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch, P.; Jongeneel, S.; Rovers, V.; Neumann, H.-M.; Airaksinen, M.; Huovila, A. Citykeys List of City Indicators, 1st ed.; CITYkeys: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Neely, A.; Adams, C.; Kennerley, M. The Performance Prism; Financial Times/Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Nesticò, A.; Maselli, G. Sustainability indicators for the economic evaluation of tourism investments on islands. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 248, 119217–119227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesticò, A.; Fiore, P.; D’Andria, E. Enhancement of Small Towns in Inland Areas. A Novel Indicators Dataset to Evaluate Sustainable Plans. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| MODEL CHARACTERISATION | |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Definition of evaluation CRITERIA |

| Step 2 | Analysis of the small town’ INVARIANTS |

| Step 3 | Definition of SUB-CRITERIA |

| Step 4 | Construction of the evaluation INDICATORS datasets |

| Step 5 | WEIGHT assignment |

| Main Intervention | Single Actions |

|---|---|

| Recovery of buildings (for a total of 1043 m2 of net surface area) to be converted into social assistance and tourist-residential facilities for the elderly |

|

| Renovation of the two main squares in the historic town centre (Piazza Sedati and Piazza Municipio) next to the recovered buildings |

|

| Rehabilitation of footpaths and streets in the historic town centre |

|

| Free Wi-Fi to cover the entire historic town centre | - |

| Creation of community vegetable gardens |

|

| Creation of the Wellbeing Path (via Trono and via Portella) |

|

| Creation of common areas for guests |

|

| Recovery and valorisation of the Santa Maria delle Grazie Church |

|

| Zero Waste Project |

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

D’Andria, E.; Fiore, P.; Nesticò, A. Small Towns Recovery and Valorisation. An Innovative Protocol to Evaluate the Efficacy of Project Initiatives. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10311. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810311

D’Andria E, Fiore P, Nesticò A. Small Towns Recovery and Valorisation. An Innovative Protocol to Evaluate the Efficacy of Project Initiatives. Sustainability. 2021; 13(18):10311. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810311

Chicago/Turabian StyleD’Andria, Emanuela, Pierfrancesco Fiore, and Antonio Nesticò. 2021. "Small Towns Recovery and Valorisation. An Innovative Protocol to Evaluate the Efficacy of Project Initiatives" Sustainability 13, no. 18: 10311. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810311

APA StyleD’Andria, E., Fiore, P., & Nesticò, A. (2021). Small Towns Recovery and Valorisation. An Innovative Protocol to Evaluate the Efficacy of Project Initiatives. Sustainability, 13(18), 10311. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810311