Local Place-Identities, Outgoing Tourism Guidebooks, and Israeli-Jewish Global Tourists

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Cultural Construction of Place-Identity and Tourism

2.2. Media and the Cultural Meanings of Tourism

2.3. Tourist Guidebooks and Cultural Identities

2.4. Place-Identities: The Case of Israel

3. Method

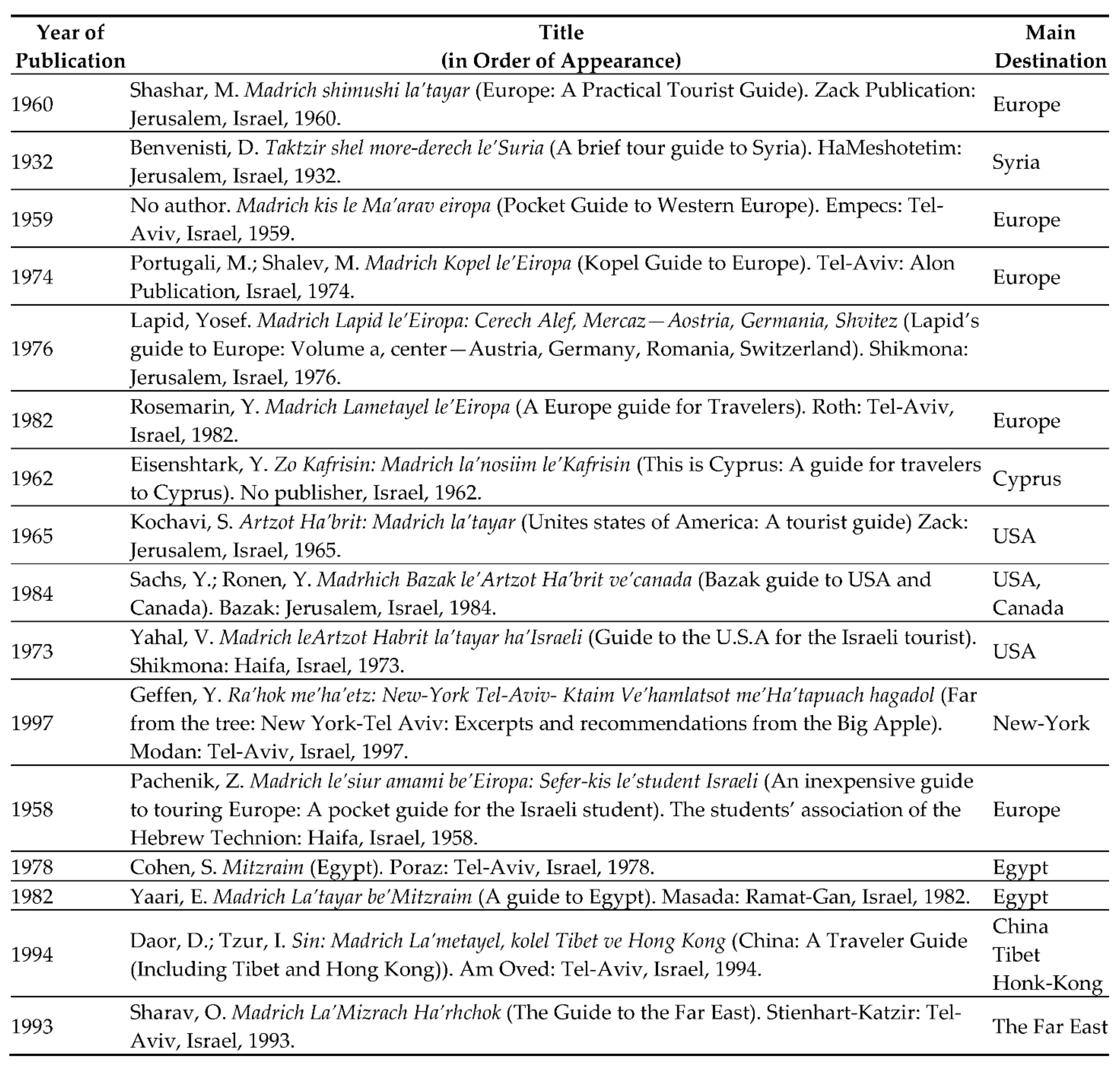

3.1. Materials and Data Collection

3.2. Research Tool

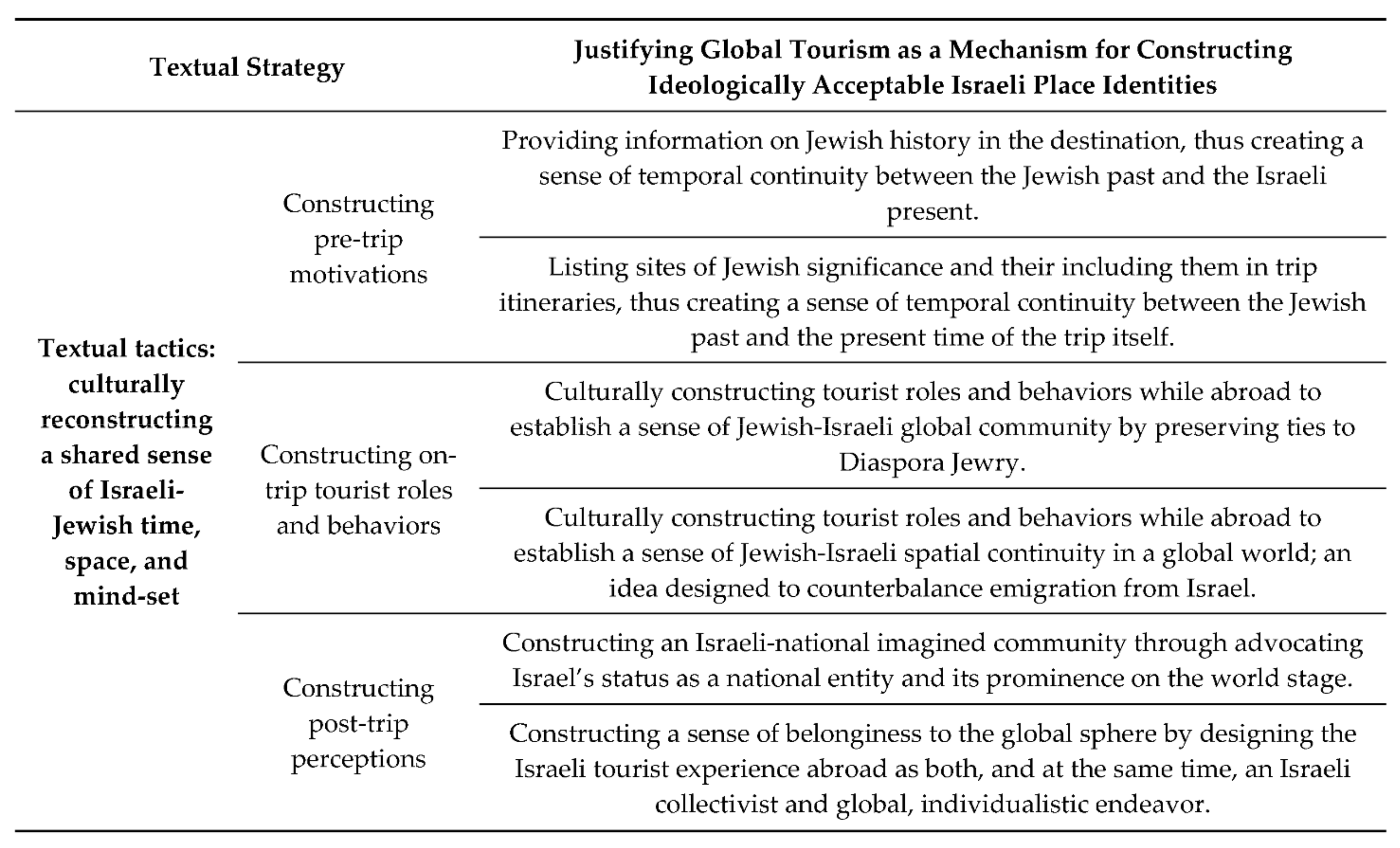

4. Results

“You will be pleased on leaving Israel, but more joyous on your return. You will see that life in Europe is not all sweetness, while in Israel is not bleakest black. Even this, in itself, is reason enough to go”.[40], p. 19

4.1. Why Israeli Global Tourism? Motivations to Travel Abroad and Local Place-Identities

- Providing information on Jewish history in the destination, thus creating a sense of temporal continuity between the Jewish past and the Israeli present.

- Listing sites of Jewish significance and their including them in trip itineraries, thus creating a sense of temporal continuity between the Jewish past and the present time of the trip itself.

Whether or not you decide to tour Germany is first and foremost a question of conscience—a reckoning each Jew must make with himself. There are thousands of Israelis that have traveled to Germany...in recent years...even ordinary tourists, Israelis who no longer see why they should skip a country in the center of Europe. The tragedy that befell our athletes at the Munich Olympics in the summer of 1972 again dissuaded many. In any case, I have no interest in persuading those who refuse to tread on German soil. My purpose is to offer a guide for those who have come to the conclusion that they will be travelling to another Germany.[50], p. 67

When you read about the long history of Jewish suffering, you wonder what made them cling so tightly to places where they were so despised. Life in the Diaspora, an exile …I have a good friend who emigrated to Germany and when we argued once he tried to explain that he had more rapport with his German neighbor than with a Yemenite Jew in Israel. And I wonder where we failed.[51], p. 664

It is impossible to visit museums, especially in the Louvre, without referencing the Holocaust—the great theft of artworks by the Nazis... Equipped with MNR lists (of artwork looted during the Holocaust), I have spent many hours walking the Louvre with its hundreds of artworks exhibited to the public, contemplating the works with a new, hard look, a gaze not shared with 99.99% of museum visitors. I asked guards but they were unfamiliar with MNR markings or where these artworks were presented. I searched and found many...in almost every gallery, from almost every period, renowned painters and anonymous masters. And it was dreadful, because beyond art I saw the sights of Auschwitz.[52], p. 60

4.2. The Role of Being an Israeli Tourist: Global Community and Spatial Continuity

- Culturally constructing tourist roles and behaviors while abroad to establish a sense of Jewish-Israeli global community by preserving ties to Diaspora Jewry.

- Culturally constructing tourist roles and behaviors while abroad to establish a sense of Jewish-Israeli spatial continuity in a global world, an idea designed to counterbalance emigration from Israel.

After World War I, most Jews questioned whether they were Jews of American citizenship or Americans of Jewish descent. Those who devoted their time to Jewish aid organizations, Zionism, politics, and religion within the Jewish community were undoubtedly Jewish American citizens, but many distanced themselves from their communities, cutting all ties to their Judaism.[59], p. 701

For many years, the horrors of the Holocaust made it clear to American Jews that they were Jews first and foremost. Their loyalty to their native US remained undiminished, but their commitment to a shared Jewish destiny and to the State of Israel as a haven for all Jews of the world became more intense and gained momentum in the Zionist movement in America, as did their generous contributions, their steady support of Israel, and the public pressure they exert for Israel whenever needed.[59], p. 704, emphasis in original

Many thanks to my common sense, that despite language and name, for personal and ideological reasons I considered emigration and exile. But I was compelled to instructed to bid goodbye to the Big Apple and return to Israel. To return to the land, which despite the State, is the most beautiful, friendly, and wonderful country in the world. And who knows, maybe one day I’ll write a guidebook about my own country. She deserves it. I deserve it. Easy.[61], p. 13

4.3. Post-Trip Meanings of Outgoing Tourism: Israeli-National “Imagined Community” and Global Israeli Tourism

- Culturally constructing an Israeli-national imagined community through advocating Israel’s status as a national entity and its prominence on the world stage.

- Culturally constructing a sense of belonginess to the global sphere by designing the Israeli tourist experience abroad as both, and at the same time, an Israeli collectivist and global, individualistic endeavor.

How to be Israeli. Being Israeli overseas is a role—a representative role. Israelis are not like everyone else, especially as among the Gentiles you are also a ‘Jew,’ a new situation for you. In most Western European countries, there is a natural tendency to treat Israelis sympathetically...however, there is nothing like a trip to Europe to demonstrate to you that the problems of the Middle East concern people only to the extent that they threaten world peace or pose risks to Western economies.[50], p. 63

Historical events temporarily separated between the peoples and created the current conflict between them, starting from the return of the Israeli nation to its land. The historical link between the two nations has never been severed. The common past of both nations is felt in the present…when weren’t the people of Israel connected to Egypt?[65], pp. 9–10

…this book... will not only educate the Israeli reader on the history of a neighboring country, but also serve as a guide for legions of Israelis crossing the short distance between Israel and Egypt’s capital cities...This book is not a dry essay; it is imbued with the belief that the cycle of wars will end and the age of peace will begin. Then, this faithful guide will serve the hundreds of thousands of Israelis who visit Egypt to become familiarized with the wonderful people sitting on the banks of the Nile.[65], pp. 9–10

…there are serious difficulties in expanding cooperation...one should keep in mind that...the dominant Egyptian viewpoint is that the peace does not mark an end to the political struggle against Israel or an abandonment of Egypt’s fundamental opposition to Zionism. On the contrary, peace is described as a reconciliation ‘strategy’ aimed at bringing Israel to cede the territories that it conquered in 1967...[66], p. 51

“You are not just a guest in Egypt. Whether you like it or not—Egyptians will see you as a representative of Israel and many of them tend to judge the country, the peace, based on Israeli tourist conduct… You may occasionally encounter annoying incidents: anti-Israel posters; antisemitic books like the ‘The Protocols of the Elders of Zion’, hateful newspaper headlines…leave it to the government and the embassy to deal with this as they see fit. Stay tourists.”[66], p. 41

Some of the most interesting experiences on the trip is the sudden discovery of entire populations completely detached from our own almighty God which do not seem to be overly distressed by this fact. There are moments when a traveler may be overwhelmed with gratitude that the Buddha in his travels stepped not a foot in Jerusalem, and left the Buddhists, at least them, indifferent to debates on prayers on the Temple Mount or questions regarding who is accepted as a Jew.[68], p. 56

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mazor-Tregerman, M.; Mansfeld, Y.; Elyada, O. Travel guidebooks and the construction of tourist identity. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2015, 15, 80–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, D.P. Mediating India: An analysis of a guidebook. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 371–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, A. Dynamic texts and tourist gaze: Death, bones and buffalo. Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 27–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnton, R. What is the history of books? In Reading in America; Davidson, C.N., Ed.; Literature and Social History; The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1989; pp. 27–52. [Google Scholar]

- Chartier, R. Cultural History, between Practices and Representations; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Chartier, R. Forms and Meanings: Texts, Performances, and Audiences from Codex to Computer; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hauge, Å.L. Identity and place: A critical comparison of three identity theories. Archit. Sci. 2007, 50, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kliot, N.; Collins-Kreiner, N. Social world, hiking and nation: The Israel National Trail. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, B.; Hidalgo, M.C.; Salazar-Laplace, M.E.; Hess, S. Place attachment and place identity in natives and non-natives. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins-Kreiner, N. Hiking, Sense of Place, and Place Attachment in the Age of Globalization and Digitization: The Israeli Case. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proshansky, H.M. The city and self-identity. Environ. Behav. 1978, 10, 147–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Strijker, D.; Wu, Q. Place Identity: How Far Have We Come in Exploring Its Meanings? Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, J.; Durrheim, K. Displacing place-identity: A discursive approach to locating self and other. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 39, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ram, Y.; Björk, P.; Weidenfeld, A. Authenticity and place attachment of major visitor attractions. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cooperman, A.; Sahgal, N.; Schiller, A. Israel’s Religiously Divided Society; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 8 March 2016; Available online: https://www.pewforum.org/2016/03/08/israels-religiously-divided-society/ (accessed on 12 September 2021).

- Noy, C.; Kohn, A. Mediating touristic dangerscapes: The semiotics of state travel warnings issued to Israeli tourists. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2010, 8, 206–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.C.; Hall, C.M.; Prayag, G. Sense of Place and Place Attachment in Tourism; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. The Field of Cultural Production; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Sociology in Question; Sage: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Culler, J.D. The semiotics of tourism. In Framing the Sign: Criticism and Its Institutions; Culler, J.D., Ed.; University of Oklahoma Press: Norman, OK, USA, 1981; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Koshar, R. ‘What ought to be seen’: Tourist guidebooks and national identities in modern Germany and Europe. J. Contemp. Hist. 1998, 33, 323–340. [Google Scholar]

- Bender, J.; Gidlow, B.; Fisher, D. National stereotypes in tourist guidebooks: An analysis of auto-and hetero-stereotypes in different language guidebooks about Switzerland. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 40, 331–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, M.J. Perpetuating tourism imaginaries: Guidebooks and films on Lisbon. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2011, 9, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrod, B.; Kosowska, A. Destination image consistency and dissonance: A content analysis of Goa’s destination image in brochures and guidebooks. Tour. Anal. 2012, 17, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iaquinto, B.L. Fear of a lonely planet: Author anxieties and the mainstreaming of a guidebook. Curr. Issues. Tour. 2011, 14, 705–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, L.M.; Collins, J.M.; Tachibana, R.; Hiser, R.F. The Japanese vacation visitor to Alaska: A preliminary examination of peak and off season traveler demographics, information source utilization, trip planning, and customer satisfaction. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2000, 9, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, V. The construction of Slovenia as a European tourism destination in guidebooks. Geoforum 2012, 43, 1099–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberson, D.N., Jr. The travel guidebook: Catalyst for self-directed travel. Tour. Anal. 2015, 20, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Therkelsen, A.; Sørensen, A. Reading the tourist guidebook. J. Tour. Stud. 2005, 16, 48–60. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, C.K.S.; Liu, F.C.G. A study of pre-trip use of travel guidebooks by leisure travelers. Tour Manag. 2011, 32, 616–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellner, D. Media Culture: Cultural Studies, Identity and Politics between the Modern and the Post-Modern; Routledge: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lewin-Epstein, N.; Cohen, Y. Ethnic origin and identity in the Jewish population of Israel. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2018, 45, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iser, W. The Reading Process: A Phenomenological Approach. New Lit. Hist. 1972, 3, 279–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Geertz, C. Thick description: Toward an interpretive theory of culture. In The Cultural Geography Reader; Oakes, T.S., Price, P.L., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough, N. Analyzing Textual Discourse: Textual Analysis for Social Research; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, J. The concept of genre in information studies. Annu. Rev. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 339–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazerman, C. Speech acts, genres, and activity systems: How texts organize activity and people. In What Writing Does and How it Does it: An Introduction to Analyzing Texts and Textual Practices; Bazerman, C., Prior, P., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bazerman, C. Genre as social action. In The Routledge Handbook of Discourse Analysis; Gee, J.P., Handford, M., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013; Chapter 16; pp. 226–238. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia, V.K. Analyzing Genre: Language Use in Professional Settings. Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Shashar, M. Madrich Shimushi la’tayar [Europe: A Practical Tourist Guide]; Zack Publication: Jerusalem, Israel, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Benvenisti, D. Taktzir Shel More-Derech le’Suria [A brief tour guide to Syria]; HaMeshotetim: Jerusalem, Israel, 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Conforti, Y. The New Jew in Zionist thought: Nationalism, ideology, and historiography. Israel 2009, 16, 63–96. [Google Scholar]

- Meyers, O.; Zandberg, E.; Neiger, M. Prime time commemoration: An analysis of television broadcasts on Israel’s Memorial Day for the Holocaust and the Heroism. J. Commun. 2009, 59, 456–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebman, S.C.; Don-Yehia, E. Civil Religion in Israel: Traditional Judaism and Political Culture in the Jewish State; University of California Press: Berkley, CA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Zandberg, E. Critical laughter: Humor, popular culture and Israeli Holocaust commemoration. Media Cult. Soc. 2006, 28, 561–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovy, J. Don’t buy Volkswagen! The Herut Movement and the question of Israel-Germany relations 1951–1965. Holocaust. Stud. 2020, 26, 283–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrich kis le Ma’arav Eiropa [Pocket Guide to Western Europe]; Empecs: Tel-Aviv, Israel, 1959.

- Portugali, M.; Shalev, M. Madrich Kopel le’Eiropa [Kopel Guide to Europe]; Alon Publication: Tel-Aviv, Israel, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Lapid, Y. Memories After My Death: The Story of My Father, Joseph “Tommy” Lapid; Thomas Dunne Books: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lapid, Y. Madrich Lapid le’Eiropa: Cerech Alef, Mercaz—Aostria, Germania, Shvitez [Lapid’s Guide to Europe: Volume a, Center—Austria, Germany, Romania, Switzerland]; Shikmona: Jerusalem, Israel, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Rosemarin, Y. Madrich Lametayel le’Eiropa [A Europe Guide for Travelers]; Roth: Tel-Aviv, Israel, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Inbar, A. Ta’anugot Pariz [The Pleasures of Paris]; Babel: Tel-Aviv, Israel, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ram, U. The Globalization of Israel: McWorld in Tel Aviv, Jihad in Jerusalem; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Graburn, N.H. The anthropology of tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1983, 10, 9–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raz-Krakotzkin, A. Exile within sovereignty: Critique of “the negation of exile” in Israeli culture. In The Scaffolding of Sovereignty: Global and Aesthetic Perspectives on the History of a Concept; Ben-Dor Benite, Z., Geroulanos, G., Jerr, N., Eds.; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenshtark, Y. Zo Kafrisin: Madrich la’nosiim le’Kafrisin [This is Cyprus: A Guide for Travelers to Cyprus]; Israel, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Kochavi, S. Artzot Ha’brit: Madrich la’tayar [Unites States of America: A Tourist Guide]; Zack: Jerusalem, Israel, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Gorny, Y. Bein shlilat ha’Galut le’hashlama ima [The Attitude to the Diaspora: Between Negation and Acceptance]. Zmanim. Hist. Q. 1997, 58, 102–109. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, Y.; Ronen, Y. Madrhich Bazak le’Artzot Ha’brit ve’canada [Bazak guide to USA and Canada]; Bazak: Jerusalem, Israel, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Yahal, V. Madrich leArtzot Habrit la’tayar ha’Israeli [Guide to the U.S.A for the Israeli Tourist]; Shikmona: Haifa, Israel, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Geffen, Y. Ra’hok me’ha’etz: New-York Tel-Aviv- Ktaim Ve’hamlatsot me’Ha’tapuach Hagadol. [Far from the Tree: New York-Tel Aviv: Excerpts and Recommendations from the Big Apple]; Modan: Tel-Aviv, Israel, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Yadgar, Y. Our Story: National Narratives in the Israeli Press; Haifa University Press: Haifa, Israel, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, B. Imagined communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism; Verso Books: Brooklyn, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pachenik, Z. Madrich le’siur amami be’Eiropa: Sefer-kis le’student Israeli [An Inexpensive Guide to Touring Europe: A Pocket Guide for the Israeli Student]; The Students’ Association of the Hebrew Technion: Haifa, Israel, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S. Mitzraim [Egypt]; Poraz: Tel-Aviv, Israel, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Yaari, E. Madrich La’tayar be’Mitzraim [A guide to Egypt]; Masada: Ramat-Gan, Israel, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Daor, D.; Tzur, I. Sin: Madrich La’metayel, kolel Tibet ve Hong Kong [China: A Traveler Guide (Including Tibet and Hong Kong]; Am Oved: Tel-Aviv, Israel, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Sharav, O. Madrich La’Mizrach Ha’rhchok [The Guide to the Far East]; Stienhart-Katzir: Tel-Aviv, Israel, 1993. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mazor Tregerman, M. Local Place-Identities, Outgoing Tourism Guidebooks, and Israeli-Jewish Global Tourists. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10265. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810265

Mazor Tregerman M. Local Place-Identities, Outgoing Tourism Guidebooks, and Israeli-Jewish Global Tourists. Sustainability. 2021; 13(18):10265. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810265

Chicago/Turabian StyleMazor Tregerman, Maya. 2021. "Local Place-Identities, Outgoing Tourism Guidebooks, and Israeli-Jewish Global Tourists" Sustainability 13, no. 18: 10265. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810265

APA StyleMazor Tregerman, M. (2021). Local Place-Identities, Outgoing Tourism Guidebooks, and Israeli-Jewish Global Tourists. Sustainability, 13(18), 10265. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810265