Abstract

NGOs are expected by their social mission not only to assess but to report on sustainability issues in response to the growing public awareness of the sustainability agendas. Since NGOs are globally renowned as watchdogs for advancing socio-economic development and sustainable societies, research on their efforts in this regard will help develop recommendations on how they can be better positioned as the watchdog. The purpose of this article is to review and assess the understanding of sustainability (reporting) in NGO literature as well as the barriers and drivers. The study investigates various practices of sustainability and identifies the drivers and barriers in sustainability reporting (SR). The authors reviewed 61 articles published between 2010 and 2020 on sustainability and assessed the strengths and weaknesses in the understanding of sustainability in literature as well as the reporting phenomenon in NGOs. The misconceptions in the definition of SR tend to weaken its relevance and applicability, and the reporting process is often focused on demonstrating the legitimacy of NGOs rather than improving their performance. As such, it provides more evidence in support of the need for a more holistic and all-inclusive definition that will aid regulation and enforcement. We also found that, although it is often assumed all NGOs share similar objectives, it is not always the case as there are as diverse objectives as there are numbers of NGOs and their reporting pattern varies in accordance with this diversity. The review makes a case for a more comprehensive definition of SR suitable for NGOs using four elements as well as providing suggestions for where research in this area might focus to enhance the overall body of knowledge. The study contributes to theory and practice by introducing new elements guiding the definition of SR in NGOs which supports accountability and proper functioning of a circular economy and promotes sustainable development.

1. Introduction

Although there is a widespread interest in sustainability reporting (SR) among organisations globally, this practice is most predominant among private sector businesses. A survey of the existing literature shows that Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) are far behind the private sector businesses in organising and reporting on sustainability [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. Issues ranging from poor accountability to mission drift, as well as the debate on whom accountability should be provided to, either the donors or others such as, the beneficiaries or other stakeholders, has seen an erosion of trust in NGOs; problems associated with the use of reporting index/standard and/or legal requirements are identified to have largely contributed to this [8,9,10]. NGOs are expected not only to assess but to report on sustainability issues in response to the growing public awareness of the sustainability agenda [11,12,13,14]. References [6,15] pointed that NGOs are well suited to pursue sustainability agendas not only because of the public trust in NGOs [16] but because they are a more active sector in organising and providing welfare services to the needy compared to the public sector. The operational impacts of NGOs in society are enormous [17,18], yet only a few people are privy to their activities, commitment to societal wellbeing, and the improvement of living standards of the people and general quality of life. SR is a concept that builds on accountability and transparency [1,16,17] and thus, it is important for NGOs to show how they themselves have championed this course in order to enhance their credibility [19], improve their legitimacy and better position themselves as SR promoters. [20] argued that non-profit organisations have been at the forefront of promoting good corporate behaviours through SR and accounting practices. However, if this is the case, there must be a clear understanding and internalisation of the concept not just in theory but in practice. In line with this, [21] called for NGOs to unite for sustainability cause as sustainability question surges in NGO.

Unlike corporate firms, NGOs operate on donor funds which are donated on an altruistic basis, to see a society that is functioning for the betterment of both the present and future generations of society. Being guided by social mission, they do not generate profit which can be re-invested to achieve organisational goals nor reward those through whom the organisation is funded. As a result, greater pressure falls on them to disclose information about their operations [22], this pressure does not only come from the fund providers but from the user public whose needs are meant to be addressed by those funds. In addition, NGOs have the trust of the public as selfless organisations acting in the interest of the people to ensure that private firms, and the government by extension, are not only accountable to the people but are seen to be accountable and fair. Therefore, it is expected that their reporting process should capture these intricacies as they are guided by their social mission [23,24,25,26].

Since NGOs are reputed for fostering and advancing positive socio-economic development in society, a better understanding of their efforts towards sustainability and reporting on it will definitely help in developing recommendations on how best they can assume the role of sustainability promoters albeit more creditably [17,27]. Similarly, a comprehensive understanding of the ways NGOs operate especially in developing and emerging economies, as well as their interaction with diverse stakeholder groups, will help to broaden the perspective on achieving sustainability goals. For example, while there may be many programmes addressing issues of poverty and lack in the global south by NGOs, a number of them still exist in isolation and there is limited research into the approaches to organisational sustainability among the NGOs [27]. This includes a deeper understanding of their self-perceived roles in the community, the drivers and barriers of sustainability efforts, and the factors that are important in fostering sustainability in the areas of social and economic life, governance, and the environment. It is important to first provide insight into the way NGOs perceive and understand SR and then move forward to assert their role in the overall interest of society and life in general since literature argues that SR aids transparency and accountability [17]. This has become even more important now that life and health, protection and/or improvement of which form part of the mandate of NGOs, seem to be globally threatened either by climate change or by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Although this literature review reveals heterogeneity in the definition of SR, there are divergences in the understanding of the topic in literature. The foremost definition is in line with the United Nations (UN) Brundtland Report of 1987, presented at the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED) [28]. The report states that “SR is meeting the needs of the present without compromising the needs of the future” [29]. However, this relates specifically to sustainable development instead. Many others defined it in the perspective of [30] triple bottom line (TBL) which stipulates it is a report on the environmental, economic, and social activities of a business [4,11,24,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38]. While others refer to it as corporate social responsibility [39], some say it is accountability [19]. A good number of authors also refer to SR as gaining financial independence [40,41,42] while others refer to it solely as a report on elimination of toxic waste [43,44], or environmental protection [45,46] or simply as reporting on developmental practices of organisations [7,47].

While none of these definitions are entirely wrong either for the NGO community or for-profit organisations, each appears to be limited in scope and falls short of the underlying meaning upon which SR is embedded and the equivalence that positions SR as a global concern [48,49]. For instance, the definition by the Brundtland Report that says it is meeting the needs of the present as well as those of the future can only refer to sustainable development and it is contestable. First, it is questionable whether the needs of the present can ever be met (in their entirety) as the definition suggests, not to talk of the needs of the future generation that are somewhat unknown at present. Secondly, this definition seems to be merely addressing (present) challenges to future generations’ ability to meet their needs, and again, it appears to be only focused primarily on human interests [50]. To a large extent, some of the definition takes a financial viewpoint [39,40]. The approach may not be suitable or wholly adopted by NGOs as it seems to enable some moral equivalence between inter-generational equality in the Western world and intra-generational inequality in the developing/underdeveloped countries of the world [51]. In this sense, [7] argued in his conceptual inquiry into the understanding of sustainability that the current definition is not only ambiguous but over popularised and does not spur NGOs for positive social change.

Prior literature in this area of research comprised a systematic review on social and environmental disclosure in higher education [52,53] or a structured literature review on corporate SR (private sectors) [41,54,55] or on SR in the public sector [56]. Studies to synthesise, summarise, and identify trends on SR in NGOs for future research and formulation of policies are rare. For example, for-profit literature has identified a number of drivers and barriers of SR, but studies that explicitly articulates this for the third sector, especially the NGOs are either missing or limited in research [56,57,58]. While we agree with this ambiguity highlighted by [7], his study failed to provide a perspective on how this should be conceived (in NGO) in order to enhance the delivery of the positive change he argued for. Further, our study reaches conclusion through an empirical inquiry process, unlike his study. This study fills this gap and extends his study by highlighting a new perspective for the understanding of sustainability. This research principally attempts to bridge this gap by examining the understanding of SR, the barriers and the drivers in NGOs in order to support a framework of action for strong sustainability that preserves nature, promotes societal wellbeing and improves the quality of life by NGOs [12,15,59]. Accordingly, this research seeks to answer the following research questions:

- R1:

- What is the trend in SR in NGO literature, and what are the most addressed issues?

- R2:

- What are the active contributions of authors, and the region?

- R3:

- What are the research methodologies used by authors in this field?

- R4:

- What is the common definition of SR in NGO literature?

- R5:

- What are the emerging themes in literature (reporting practices, drivers, and barriers)?

- R6:

- What are the future research directions on SR in NGOs?

This research makes several contributions to knowledge, aside from the fact that it enriches the existing literature on SR in NGOs, this research provides insight for theoretical blending and pluralism that supports greater research applicability or the development of ‘indigenous’ accounting theory. The study unpacks the existing complexities in the definition found in literature and makes a case for a more comprehensive definition of SR suitable for NGOs. This research contributes to theory and practice by introducing new elements guiding the definition of SR in NGOs which support accountability and social mission of NGOs as well as promote sustainable development and multi-stakeholder relations. Our study synthesises the drivers and barriers of SR in NGOs as well as provide a guideline for future research development avenues in this field.

The rest of the paper is divided into three sections. The first section presents the research methodology, the second section presents the results and discussion while the last section presents the conclusion.

2. Research Methods

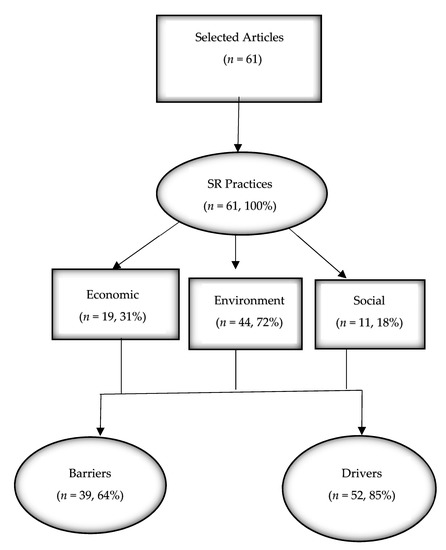

A proper systematic literature review has the ability to uncover trends [54,55,60], and shows consistencies or inconsistencies in research, including relationships, and can facilitate a path for future research as well as evaluating existing work in a particular field [2]. Effective literature review encourages theory development [53] and helps to raise arguments about the direction of existing research because it is made up of reproducible methods [61,62]. To begin, the basic definition/terminologies and inconsistencies in understanding of NGO and SR and the practices are discussed/evaluated in order to advance the knowledge of the basic concepts involved. Next is the selection of databases and search terms, the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the studies, the method of analysis, the synthesis of the findings, and the limitations of the study. Search terms were created and imported into NVivo with relevant attributes such as publication year, region, driver, barrier, and SR practices; each term was used to create a context node for each theme used to run relevant queries on NVivo. The dominant concepts in the text were transformed into codes [55,63] in order to find the presence of selected terms within the text as well as similarities under the same concept through a systematic approach. The theme classifies SR practices into economic, environmental, and social reporting, and then the drivers and barriers of SR followed (see Figure 2).

2.1. Approach

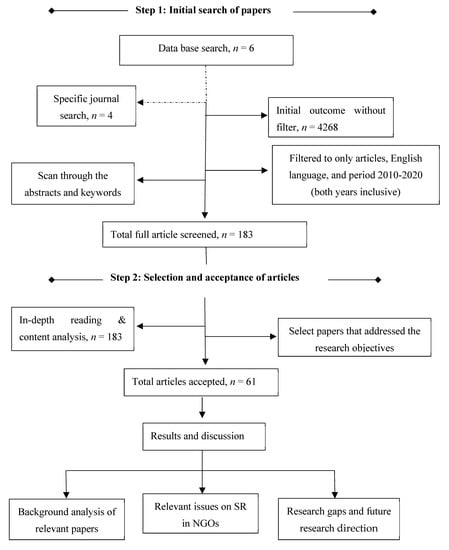

This study applies a systematic literature review as a tool to conduct this research. To aid understanding [11,33], location, material selection, evaluation, analysis, and findings were reported in a manner that supports replication. This method has been repeatedly used in medical sciences and applied in social and management sciences as well as organisational studies [64,65]. According to [64], research findings via this method have become consistent among the academic community, as well as practitioners and policymakers. This was further highlighted by [54]. The analysis process consists of two steps (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Research methodology process.

The two steps involve four stage processes. Step one consists of two stages, which involves question formulation that deals with the primary objectives of this study, definition, and delimitations of the study materials. It is followed by the assessment of the formal aspects of the material which forms the basis for subsequent analysis and includes the location of the articles by using specified search terms (stage 2). Under step two, the selected (n = 183) materials were analysed (stage 3). Each study was independently searched for the occurrence of the terms that formed the research question, giving rise to 61 articles. The structural categories which gave rise to the topic of the analysis were inductively formed using this pattern. Lastly (stage four), the entire body of material searched (n = 61) was rigorously scrutinised in accordance with the categories which gave rise to the identification of relevant themes as well as subsequent interpretation of the findings due to the heterogeneity present in the findings [2,46].

In other to ensure transparency and reproducibility, we will succinctly explain the processes involved in the systematic review including the choice of literature selection, databases, search terms, and categorisation in the subsequent sections.

A total of 61 articles were reviewed and analysed. These were articles that referred to SR in NGOs to a certain extent and included related topics such as SR practices, drivers, barriers and so on.

2.2. Selection of Databases, Search Terms, and Timing

Six databases were used [66,67,68,69,70,71]. These databases were used because of the multidisciplinary nature of the topic; they contain a wide coverage of publications in diverse fields including accounting, management and social sciences [44,72] mostly used for contemporary reviews [27]. Articles from the databases, and more specific search of some journals were of high impact factor and cut across over 20 different fields [72]. This was completed to ensure broad coverage of the topic area; however, it gave rise to duplication of the result. All the searches yielded articles from peer-reviewed academic journals, most of which were environmental, social science, and business journals.

The result of the search showed more articles from the Journal of Business Ethics, Journal of Cleaner Production, Sustainability journal, and Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal; as a result of this, to make the search even more robust, a specific search in these journals was conducted using the same search terms (as below). Further, some of the downloaded articles suggested other articles of interest that those who downloaded the article also downloaded and provided their links; this was also helpful.

This review covers a decade, from 2010 to 2020 (both years inclusive). The review started from 2010 because of the triggering effect of the 2008/2009 financial crisis on organisations coupled with the extensive promotion of GRI frameworks in the year and subsequent publication of GRI and ISO 26000 aimed at espousing the use of GRI guidelines in combination with ISO 26000 in promoting transparency and sustainability in addition to the release of NGO GRI sector guideline in the same year [7,73]. Secondly, since the focus was on contemporary research, we believe that the last decade was enough to reveal trends and show a good assessment of existing research [74,75,76] as well as giving direction for future research. The first database search was performed in December 2018 while the last search was launched in August 2021.

In order to holistically cover the topic area, a number of search terms were extensively used to conduct the research: “sustainab* report*” AND “NGO*”, “sustainab* performance* AND NGO*”, “environment* report* AND NGO*”, “sustainab* AND non-profit organis*”, “sustainab* assessment* AND non-profit organis*”, “sustainab* performance AND non-profit organis*”, “social report* AND NGO*”, “corporate social responsib* AND NGO*”, “non-financ* report*”, “triple bottom line report*”, “integrated report*”, “TBL AND NGO*”, “integrated report* AND NGO*”, “sustainab* development*”, “environment* management”, “governance report*”, “development* report*”. In order to be thorough and ensure completeness, these key words were painstakingly repeated throughout the search systematically for each database or journal site searched, although this resulted in duplication of the result as one article may appear several times.

2.3. Screening and Exclusion Criteria

The retrieved articles were manually screened using the abstract of the paper. This process led to the removal of articles that clearly did not address the topic of SR in NGOs (see Figure 1 and Table 1). The time frame for the study was from 2010 to 2020, and articles that did not fall within this range were excluded from the study. To evaluate whether an article addressed the topic of SR in NGOs, the first author and the second author independently read those in contention in full and any disagreement was settled by the third author. For ease of understanding and general application, the study was restricted to articles written in English. Review articles, books, and editorials, including comments, were also excluded from the selection. The last search was conducted in August 2021 as a final search for articles published in 2020, which identified 82 more articles for screening; the process resulted in 34 articles including duplicates. After duplicates were removed, 11 articles remained which were added to the existing number of articles. Each article was independently read by all the researchers to increase reliability. Articles that did not particularly address SR in NGOs were dropped. This process resulted in 61 articles overall (n = 61) with relevance to the topic, and these were uploaded in NVivo for analysis.

Table 1.

Inclusionary and exclusionary criteria.

2.4. Analysis Method

A content analysis was conducted on the selected articles and coded into NVivo to quantitatively analyse the content characteristics while eliminating the information source. The exploratory components were extracted, critically appraised, and grouped in clusters each of which later became a theme in line with [55,62]. This exercise was painstaking and common for document analysis where quantitative analysis of document characteristics is conducted. A systematic reduction process was inductively used to create and recreate categories and sub-categories in the selected articles using feedback loops in line with [52]. This process was also used to identify themes and classification of articles. The articles were further analysed manually to identify certain consistencies and inconsistencies within them. The core classification of the articles was first into “environmental”, “economic”, and “social & governance” because articles on these topics tend to discuss sustainability in a holistic way. Other aspects of the classification include “SR practice”, “barriers”, “drivers” (Figure 2) in order to cover the research question. Another important part of the articles was analysed and coded separately and then compared with others. An example is the SR driver (Table 4) and barriers (Table 5).

Figure 2.

Number of studied articles per the theme of classification.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Publication Trend per Theme

This review is classified into different themes for ease of analysis. Figure 2 shows the number of articles (in percentage) reviewed under each theme within the timeframe of our study. There are a limited number of articles that discussed the core of SR in NGOs; however, most literature discussed SR either as regards environmental reporting or reporting on social or economic aspects, ignoring all other aspects of SR and their inter-linkages (e.g., governance). While all the 61 articles (100%) addressed SR practices, 39 articles (64%) addressed the barriers to SR, and 52 articles (85%) addressed the drivers.

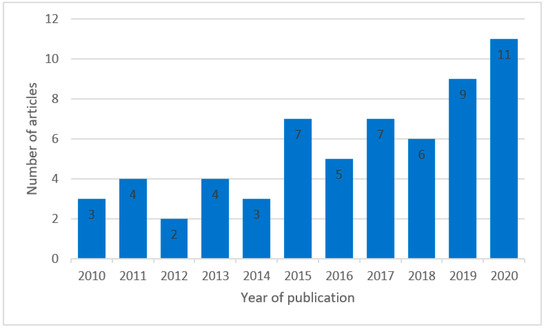

Publications Studied per Year

In order to show a trend in research on SR in NGOs, the number of publications studied per year is graphically presented in Figure 3 above. The result indicates that SR in NGOs was discussed more in 2020, and equal in 2015 and 2017 with seven articles as compared to fewer articles in the previous years. Publication on the topic was relatively the same between 2010 and 2014 before it seemed to have gained considerable attention in 2015 with about a 57% increase from the previous years; this trend continued until 2018 when publications declined by 16% but rose again in 2019. This growth may not be unconnected with the GRI’s launch of “Forward Thinking Future Focus” in December 2014 which was a combined activity review covering 2013 and 2014 and the subsequent landmark climate change agreement where 193 United Nations (UN) member states unanimously adopted 17 sustainable development goals and the promulgation of the European Union’s (EU) directive on disclosure of non-financial and diversity information in 2015 [73,76]. The trend shows that SR is a growing phenomenon in NGOs though not without some challenges in its development. The trend reveals that, although there was low interest in the subject in the beginning, it grew over time as its relevance is espoused, however, further analysis to prove this will be conducted in the subsequent section.

Figure 3.

Annual publication trend.

3.2. Assessment of Authors’ Contribution

The assessment of authors’ contributions on sustainability and reporting practices in NGOs was done to provide an insight on author’s impact on the article by ranking following [77] credit score matrix formular as below;

where n = authors’ contribution; i = authors’ rank

All contributing author is given a maximum score of 1.00 [77]. A score of 1.00 is distributed among the authors in such a way that the lead author gets the highest percentage of the credit score and the following authors share the remaining credit score proportionately as seen in Table 2 below.

Table 2.

Authors credit score assessment matrix.

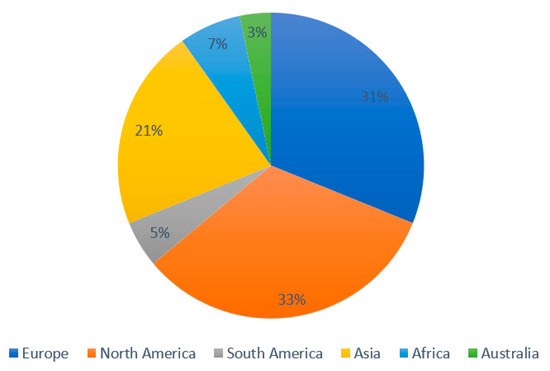

Geographical Distribution of Literature on Sustainability and Credit Scores

Table 2 below shows the list of countries where sustainability studies were focused and that contributed to research in sustainability among NGOs within the study period. In addition, it also shows the number of institutions, authors, and credit scores of authors’ contributions to the topic.

The above table is relevant in understanding active contributors to sustainability discussion in NGOs and the underpinning industry practices of the subject in specific areas and places. Based on this, country-level analysis of studies on SR in NGOs may help to provide some clarifications, awareness, and relevant insights on the extent of the understanding and the advancement of sustainability by the sector. The table above was presented on the basis that a country should have at least a score of one and must have a minimum of two institutions and two authors [78]. This was implemented in order to manage the high number of authors and countries covered in the study. USA and UK are the top two countries contributing to SR discussion in NGO with a score of 9.88 and 4.81, respectively. In USA, 17 authors from 15 institutions have actively contributed to the discussion. This finding is consistent with global attention that issues of sustainability have drawn over the years with US as the largest funders of NGOs demanding accountability [22,79,80]. A similar explanation follows UK with a score of 4.81 which re-enforces UK’s dominant lead on the sustainability debate [19]. The research suggests an increasing growth in sustainability research in Asia continents as well with an average score of 1.3 could point to the improved awareness and increasing commitment to meet the sustainable development goals (SDGs) in the continent [81].

The review shows that most of the articles on sustainability in NGOs are from US and UK. Others were fairly distributed within the continents (Table 3). This is consistent with the findings of [6,82] as well as [14,75,83] who posit that studies in SR are more largely concentrated in Europe and the American continent. This prompted the authors to analyse it by continent [84,85] in order to get a clearer picture of this claim or otherwise. Further analysis (Figure 4) shows that 38% of the study are from America, 31% from Europe, 21% from Asia, and only 7% and 3% are from Africa and Australia, respectively. Besides, the continent of Africa has not received a fair share of interest in this all-important topic despite being a hot spot for NGOs as a developing continent. The underlying ideology of NGOs is to espouse equality, social justice, improved living standards, and enhanced quality of life in general. All these are common problems associated with developing or underdeveloped countries of Africa.

Table 3.

Active contributors to SR literature.

Figure 4.

Distribution of studies by region.

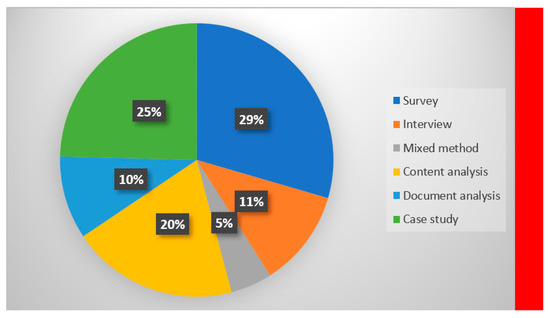

3.3. Methodologies Adopted for Studies on SR

The relevant papers analysed show six dominant research methodologies used by existing studies on SR. These are survey, interviews, mixed-method, content analysis, document analysis, and case study research. Figure 5 shows that survey and case study research methods are the most frequently used method for investigating SR, accounting for 29% and 25%, respectively. This finding appears consistent with the need for robust empirical evidence to argue the narratives and policy development on SR in the third sector and validate theoretical underpinning of the relevance of SR in the sector [78,86,87,88]. Having been used by 20% of the surveyed articles, content analysis was the third most frequently used method. This is consistent with [39] findings, that content analysis gives a clear picture of the situation. Using a content analysis explored how organisations manage their SR process; they specifically focused on internal factors associated with SR [41,54]. The results show that, although they are ranked top in the scheme, the sequence of structures, systems, and processes in which SR is managed varies across organisations. The next most used methods, according to our survey, are interview and document analysis with 11% and 10%, respectively. Again, this is consistent with [14,15,43] who used interview analysis for examining beliefs about the motivations for NGOs in joining the international NGO (INGO) charter because of its ability to explore perspectives and show trends. The findings support the constructivist explanation of NGO behaviour. This shows that survey research, to an extent, gives a detailed explanation of a phenomenon. Mixed-method is the least adopted method in connection with SR with 5%. This suggests that mixed-method comprising survey research (quantitative) complemented with an interview (qualitative) may be a relatively new concept in this area or its use may not be very well known/understood. However, given that survey and interview methods were independently highly used, a combination of the two (mixed-method) could provide a more balanced view and a nuanced explanation of a phenomenon, and hence is to be recommended. This view aligns with those of [89,90] who support the use of mixed-method and aver that it is ideal in social science research because it provides a comprehensive empirical description of the phenomenon being investigated.

Figure 5.

Research methodologies adopted in SR research.

3.4. Understanding of SR

Until now, the adoption and understanding of SR in NGO literature is inconsistent and relatively unclear as demonstrated in Figure 6 below. The figure highlights the dominant word used by researchers in defining SR which represents the extent of the recurrence of the same words within the sample papers. The keywords of the bibliometric study are “sustainability”, “need”, “future”, “economic”, “social”, “assessment”, “environment”, “accountability”, “generation”, “impact”, “measurement”, “society”, “responsibility”, “outcome”, and so on.

Figure 6.

Word cloud showing the dominant definition adopted in the literature.

While the literature review shows divergencies in the understanding of SR, and in the understanding of the topic, the most common definition is in line with the United Nations (UN) Brundtland Report of 1987. As highlighted earlier, the report was presented at the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED) [28] and accounts for 64% of the definitions found in the literature. The report states that “SR is meeting the needs of the present without compromising the needs of the future” [29]. This was a direct response to sustainable development as was discussed in the report. Ref. [7] argued that a look into the meaning and use of the term “sustainability” in the NGO sector is critical and will obviously advance theory and practice. In his reflections on sustainability and resilience, he argued that adopting the Brundtland definition might challenge the goals of NGOs and constitute an obstacle for positive social change that NGOs consistently pursue. The phrase in defining sustainability reporting had taken shape as discourses, for example, metaphors are used to ascribe meaning to both the NGOs and their social mission [7,15,59]. Sustainability is a boundary term [46,55] that is derived from ecology, economics, and politics, and as a result, has implied multiple meanings in the NGO sector [7].

While we argue for a definition that reflects the core mandate of NGOs embedded in their social mission, we posit that the current understanding of it appears to be limited in scope. Sustainability should be seen as a means to an end in NGOs and not an end itself. For instance, concerns have been raised that sustainability might lose its relevance if construed in that manner seen with the Brundtland report [7,91]. There is no guarantee about meeting the needs of the present in their entirety as the definition suggests and also meet the needs of the future generation that are somewhat unknown at present. In line with this, [92] highlighted that the current reporting practices in NGOs are not compatible with their nature as mission-driven organisations, hence do not meet stakeholder requirements. As highlighted earlier, we noted that the definition seems to be merely addressing present challenges to future generations’ ability to meet their needs, which again appears focused primarily on human interests [50,91]. This finding aligns with the findings of [7]. To a large extent, the definition takes a financial viewpoint [39,40,42]. For instance, in the study of the factors influencing SR in NGOs by [42], they found that access to donor funds has a significant influence on sustainability and it is a key driver for SR processes in NGOs.

Generally, SR has contested analytical importance, application, and scope with a strong positive resonance [48] and outcome but this definition in the literature above is silent on ‘assessment processes’, ‘outcomes’, and ‘quality of life’ as it pertains to both human beings, animals, and plants [50], which is the bedrock of the WCED. The definition could be used to indict the over-consumption of resources of the rich (donor group) by the poor and the disadvantaged or the demand for regular financial support by the latter [9,50]. In addition, if sustainability is conceptualised in this way, it may encourage practitioners to jettison the structure, histories, and processes that have led to, and continually reinforced, inequality in global and local distribution of resources [18,93]. This includes the intended outcome of SR which results in sustainable development ultimately. SR as a term not only conveys its meaning but its assessment outcome which is universally portrayed as a moral good, and this makes an act described as sustainable difficult to criticize [48]. On the other hand, defining sustainability on the basis of TBL which is anchored on people, planet and profit appear to be inherently faulty because of NGOs’ non-inclination to profit. This definition seems unbalanced and parochial in addressing the needs that it is meant to serve; given the circumstance that it is financially focused, it does not recognise that NGOs are largely dependent on financial resources which come first before the need for surplus that NGOs make to ensure their long-term survival. This misconception tends to pitch NGOs’ reporting merely towards achieving legitimacy. Moreover, reporting to attract donations or because of pressure from stakeholders could explain their resource dependency nature.

The definition of SR should be an embodiment of the mission and vision of NGOs [7,94], a reflection of impact, and a demonstration of the outcome. For instance, using governance theories, [15] found that NGOs have the ability to effect great changes through collaborative partnership and confrontational tactics which enhances stakeholder participation in organisational decision-making processes. However, this does not seem to be the case as seen in the discussion above. To address the weaknesses vis-a-vis inconsistencies in the definition and reporting practices found in literature, it is suggested that SR be defined to reflect core issues that the Brundtland Report intended to address, which was about improving the quality of life. Resulting from the analysis of the definitions, these issues, otherwise known as the aim of the WCED, were missing or not succinctly encapsulated. Literature does not seem to adequately cover the underlying elements of sustainability. The main features which underscore the very essence of the commission by the UN in 1987 (Brundtland Report) and which should inform the definition have not been well captured.

As such, we infer that to effectively define SR for NGOs, the definition should clearly demonstrate the following elements which contextualises the social mission of NGOs [13,94]:

- Accountability mechanism;

- Assessment and outcome;

- Governance and impact;

- Quality of life.

As NGOs pursue sustainability agendas, it is pertinent to align these efforts with their social mission which will be consistent with their values [94]. Since NGOs are motivated by a commitment to their social mission and transparency to diverse stakeholders [95], these elements will espouse their “sense of moral duty and reawaken their awareness of obligation” to the stakeholders [22]. This will simulate SR as a social construct that entrenches self-reliance. Sustainability is expected to reinforce equitable local and global distribution of resources, encourage and strengthen the structures and processes of development agents when conceptualised and acted upon this way. This will reduce the popularisation of SR as an incentive to the community, limit agency cost by entrenching responsibility accounting which stakeholder theory espouses [1,96]. It will ensure commitment to NGO social mission [13] and attention to the quality of life [50], thereby enhancing their legitimacy.

3.5. Relevant Themes on SR

3.5.1. Reporting Practices

The distribution of the reviewed literature according to SR practices is narrow. Most of the literature identified SR either from the perspective of environment, or social or economic perspectives. A brief explanation of this concept from the NGO lens and a summary of what NGOs are reporting in line with the reviewed papers are presented below:

3.5.2. Environmental Sustainability

Most of the articles addressed SR practices in regards to the environment only. This is not surprising because the concept of sustainability as a European term originated from forestry [17,97]. This aspect of sustainability mainly emphasises the preservation of biodiversity and the ecosystem as well as the protection of the planet from the worsening signs of climate change. The proponents of this aspect of SR assume sustainability principles are promoted as long as the environment of business operation or the larger environment in our community is protected from events capable of threatening life and development. For instance, environmental regulation arose from the need to protect human beings and public health from the dangers posed by the environment and to protect the environment from human impact [34]. As such, the reviewed articles reported issues on, material use, energy consumption, water use, biodiversity, effluent and waste, environmental compliance and grievance mechanism, transportation [42,44,92].

3.5.3. Social Sustainability

The social aspect seems to be a direct response to corporate social responsibility (CSR). Although this provides a narrow view of social SR, it aligns with the understanding of the concept of sustainability as evidenced in the NGO literature. It explains the interdependent nature of business and society and asserts that in order to promote and fund sustainable development on an agenda driven by the society and the private sector, the mutual benefits of business and society have to either come from or be imposed on societies and their respective businesses [91]. They argue that sustainability will be able to put pressure on national and international corporations to adopt a better business model that is socially-oriented. The most reported issues were on the aspect of employment, labour/management relation, occupational health and safety, education and training, equal opportunity, human rights, public policy, non-discrimination, stakeholder engagement, and social compliance [14,41,77].

3.5.4. Economic Sustainability

The economic aspect was part of [30] triple bottom line report [17]. All the reviewed articles that discussed economic sustainability were in terms of NGOs’ ability to continue to self-fund their operation and or continue to generate profit. This is a complex phenomenon in NGOs because of their resource-dependent nature and non-profit making disposition.

Literature seems to be silent on the governance aspect of sustainability, the management of which drives reporting. In order to have a more meaningful discussion on the sustainability debate, the governance principles have to be entrenched and holistically assessed and evaluated [17]. Integration of the governance mechanism will more likely result in accountability, with better assessment outcomes projected towards improved quality of life. The reported issues were concerned with economic performance, indirect economic impact, ethical fundraising, resource allocation, and anti-corruption [7,41,59].

3.6. SR Drivers

The motivation to report on sustainability as identified in the literature is quite diverse, ranging from internal to external factors, and we have grouped them into these two categories for ease of analysis and understanding (Table 4). The external factors, which accounted for about 55% of the articles, include stakeholder pressure, desire to gain donor attraction, the need to minimise negative environmental impact (e.g., climate change footprint), collaboration/desire to promote sustainability efforts, media exposure (impression management), and financial crises. Others include societal/cultural pressure, level of funding/donor capacity, and so on.

Table 4.

Most reported drivers.

The most dominant drivers are stakeholder pressure and the desire to attract donors. This finding aligns with the position of [42,57] who assert that the level of reporting is significantly affected by the demands of the stakeholder group. For instance, external stakeholder groups such as the donors, government, competitors, and the community of beneficiaries exert or are expected to exert substantial influence on the management of NGOs on their reporting. It is also of note that some NGOs engage in SR not because of its benefits to their stakeholders but to be able to attract donors. Resource dependency explains that organisations establish relationship with others in order to obtain the resources they may need to pursue their objectives. So the need for resources could dominate NGO relationships with donors [46,100] which has the capacity/potential to compromise their ability to disclose and account transparently. This to a large extent explains why the issue of voluntary reporting will continue to impact the sustainability performance of not only the NGOs but the public and private sectors [25].

The internal factors include reputation, organisational capacity, transparency, accountability, impression management, organisational size, desire to create value, management interest, performance, accounting for 45%. While this suggests that external factors constitute more of the drivers, further research involving the NGOs themselves is needed to ascertain which stakeholder group is driving SR reporting since literature suggests that the understanding of the subject itself is unclear. There is a need to know whether SR is driven by internal management principles or by external pressure, particularly from the donors whose resources are used to run the NGOs, and why.

The internal drivers are somewhat controllable while the external drivers are not. This explains why lack of regulation is heavily impacting reporting on SR by NGOs. External motivation such as law mandating all legally registered NGOs to produce SR will definitely improve and increase the reporting process and enhance NGO legitimacy. Since legitimacy theory explains that NGOs will achieve legitimacy when they balance the social values implied by their activities and the norms of acceptable behaviour in the society; this can be done through information disclosure.

It is unclear whether the identified factors will influence SR in a developing country, especially in Africa. Most local NGOs in Africa are owned by politicians and celebrities, such as ex-footballers, movie stars, and musicians, and in some cases for philanthropic purposes. Among these groups, the understanding of philanthropy and accountability is different and there is also a mismatch between the operational scope of these NGOs and the real intention for their existence. While most of the local NGOs are owned by politicians or their cronies [101] whose interest on behalf of the general public is questionable, others may not really understand the concept or mechanisms for pursuing sustainability and/or accountability. This implies that the population of the less privileged and the deprived will continue to suffer, and the targeted need will remain unaddressed, thereby reducing the quality of life, and fuelling underdevelopment and poverty all of which negates the NGOs’ existence ab initio since they are primarily set up to fight these by improving the quality of life.

3.7. SR Barriers by NGOs

The most common barrier identified in the literature is the voluntary nature of SR, accounting for 43% of the identified barriers (Table 5). This is consistent with the findings of [25,59]. Implementation of SR and performance measurement systems provides an opportunity to align NGOs with their mission. However, a holistic implementation of SR, as well as other social performance measures, will not readily occur if it continues to be voluntary [72]. This also explains why the highest internal driver is the need to improve their reputation. If SR is driven by reputation, then NGOs will not be reporting to communicate accountability, assessment, outcome, and impact which enhances the quality of life and drives sustainable development. However, this might not be attainable without sustainable development of organisations and the attendant systems [87,96]. The lack of reporting is mostly because reporting on sustainability is not a legal requirement for the organisation, so only those who foresee any benefit from reporting on sustainability or those who feel compelled either by the donors or internal management will engage in SR. This smacks on the privileges of stakeholders (especially the beneficiary group) and could affect NGO performance since stakeholder theory shows that taking all constituent groups into account could lead NGOs to a higher level of performance. So, if NGOs report only when they feel the need, they have not taken all constituent groups into account since reporting is an integral part of accountability. The fact that NGOs are resource-dependent makes SR imperative, it would ensure that donors including prospective donors would see and appreciate their programmes and commitments. Other identified barriers include lack of regulation, bad government policies, lack of assurance, lack of basic knowledge on SR, lack of uniform indicators, lack of expertise for the report, culture, resource dependence, cost of reporting, etc.

Table 5.

SR barriers.

Due to the voluntary nature of SR, organisations are not generally mandated by a regulatory authority to produce a report on their sustainability practices [27,102]. For this reason, third sector organisations such as the NGOs are expected to double their efforts in bringing the issues of sustainability practices into the limelight in order to enhance performance and overcome these barriers. This effort will also enhance their legitimacy since NGOs’ good behaviour towards the environment and society promotes legitimacy.

3.8. Paths for the Future

Earlier sections presented different topics under which SR was discussed in NGO literature; some of these topic areas have been discussed in more detail while further research is required in some underrepresented areas in the literature to further enrich/exhaust the topic and inform scholars. The following section will focus on the main areas of research attention as identified in this research.

3.8.1. Disclosure of Sustainability Information

At the beginning of this paper, we noted that [1,2] argued that NGOs lag far behind the private sectors in reporting and organising for sustainability. Our findings are consistent with [1,6] but our study also points out that NGOs do not explicitly separate internal motivation to report on sustainability from external motivation. Whom to account to and to what extent, are not clear in NGO literature. Our review confirms this observation. Most literature on sustainability has focused on the determinants of SR, while other studies focused on the quality of SR [15,44,103] which is key in assessing the true and fair view of NGOs’ performance on sustainability. However, little or no attention is paid to whether the report is biased towards those who prepared the report or the donors. Although [92] looked at it from the perspective of the stakeholders, they did not consider the donor’s influence and quality of the report. If the report is prepared specifically to meet the needs of the donors, then the quality is in question resulting from bias, and the same applies if it is prepared to address internal governance goals. While SR is not exclusively about disclosing positive or negative incidences, research shows that voluntary reporting allows NGOs to report on positive gains [102] as a form of impression management here referred to as “sustainability washing” (a situation where NGOs claim to be compliant with SR principles but are not in reality). Although Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) guidelines state that the quality of SR and the materiality of its content depend largely on the balanced reflection of its positive and negative incidents [104], none of the literature reviewed investigated disclosure of negative incidents. In addition, since the review shows that most literature on SR is dominated in Europe and America, research into SR adoption in developing countries especially in Africa needs to be explored. This is important and urgent in advancing efforts towards sustainable societies and in achieving the SDGs

3.8.2. Potentials of SR for Organisational Learning

Just as in private organisations, the influence of SR for organisational learning and change is not yet fully explored in NGO literature. As a sequel to the analysis, we propose that NGOs should take an experiential-oriented approach to SR where the lesson of sustainability is reflected in the organisational behaviour of different NGOs. Attention of NGOs should not only be on what to do to facilitate SR but on how NGOs can change their operations in order to foster SR and integrate the lessons thereof into their internal governance mechanism. For instance, it is surprising to note that the literature did not mention the need for improved organisational performance as part of internal motivation to report on sustainability. It is important to know how NGOs themselves are applying sustainability principles in their operation which includes issues regarding energy consumption, waste disposal, recycling and general circular economic issues. This finding is similar to the finding of [52] in the study of SR in higher education. The level of changes that could be facilitated through SR and/or the potential of SR to facilitate change in NGOs should be explored. This cannot be done simply by studying published reports by NGOs but through an in-depth, exploratory case study research and/or a survey design on the topic. Only a few case studies are available within the NGO literature and the very few are often critiqued for making conclusions that are not based on sufficient evidence [17]. Therefore, a detailed description of the experiences of NGOs with SR through a sound theoretical framework needs to be explored in more detail.

3.8.3. Stakeholder Engagement Process and Its Influence on SR

The influence of certain stakeholder groups involved in SR is also underreported in NGO research. Future research could examine stakeholder engagement processes in NGOs with a view to enhancing accountability and effectiveness with which aid services are delivered; with emphasis on downward accountability especially in developing countries. Literature has identified internal and external stakeholder groups in SR. However, it is not clear which internal or external stakeholder groups are involved in SR as well as their role in SR [105]. Literature states that SR gained attention as a result of efforts to satisfy stakeholder demands [4,98], and this study has made similar findings.

The influence of these stakeholder groups can be further studied and if positive, they can be supported in order to foster the internalisation of SR benefits among NGOs. Research could possibly explore the adoption of SR based on expectations of different stakeholder groups and their influence, so the question will concern efforts to integrate the stakeholders into the mainstream of SR depending on what their influence is and bearing in mind that different NGOs pursue different objectives. In the study of [92] and that of [41], it was shown that SR does not meet stakeholder requirements.

3.8.4. Drawback to SR

As stated earlier, one of the major challenges of SR is the voluntary nature of SR reporting. Future research might focus on how to overcome this especially in developing economies where reporting infrastructure and regulatory frameworks are poor or non-existent. Literature also identified factors such as cultural differences, issues of assurance on the report, climate change, bad government policies, resource dependence, etc. as part of the barriers. Although these factors might result in a general lack of incentive to report on sustainability, it is worth exploring further how these factors actually constitute a barrier and/or their impact on the quality of the SR reports. Subsequent studies could also possibly suggest solutions to the barriers to document or recommend this to the NGOs for learning and change [27,55]. Furthermore, it is not clear what impact the absence of these factors will have on the pursuit of sustainable development goals. Therefore, future research could explore the role of these factors towards ensuring a better quality of life since the driver of SR is predominantly shown to be pressure from stakeholders and desire to increase reputation. There is no denying that the impact of climate change on the environment is huge [106], and this threatens continued human existence on earth. Future research might explore the readiness of NGOs towards climate change adaptation. It could as well explore the role of NGOs towards minimising the impact of climate change and possibly the effect of their impact on the human environment in order to improve the overall quality of life as conceived through their mission. Perhaps, it could explore the impact of the current COVID-19 pandemic on the operations and management of NGOs. This is because more is expected from them since they are reputed for advancing positive corporate behaviour as well as acting as a watchdog for other organisations [17].

3.8.5. Uniform Indicators

One of the barriers to SR discussed earlier in this paper is the lack of a uniform reporting index. The GRI provides a guideline for reporting on sustainability; however, the applicability and otherwise suitability of these guidelines in every culture and environment is questionable. Due to the diversity of NGO operations coupled with the environmental differences and other dynamics in NGO operations, future research could explore ways in which the reporting index could evolve through a local framework based on the engagement of the different stakeholders that could be culturally or environmentally specific. This will ultimately ensure a better outcome for sustainability performance and increase participation through a change in the NGOs’ process that not only facilitates SR but fosters sustainable development integration into their internal operations.

4. Conclusions

NGOs make invaluable social, economic, environmental, and developmental interventions in a society in order to address issues resulting from globalisation, market failures, poor regulation, and bad governance. However, recently attention has been focused on the negative consequences of NGOs’ actions and perceived problems in their governance structure and accountability practices especially in relation to their SR practices. This paper provides a systematic review of the extant literature on SR for a decade from 2010 to 2020. The review succinctly discusses the concept from the NGOs’ point of view in order to provide a platform for a more in-depth discussion in the hitherto neglected area, as well as to redirect the attention of researchers and to finally provide guidance on where the future lies ahead in SR research in NGOs. We note that the adoption and understanding of SR in NGO literature are inconsistent and relatively unclear. This study tries to shift attention from the Brundtland Report of 1987 that defined sustainability as “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations from meeting their own needs”. Incorporating NGO mission and vision in the definition is a major contribution of this paper, aside from opening a new horizon for future research involving several perspectives on SR in the light of NGOs. As noted by [7], the understanding of the term “sustainability” when applied to the NGOs with respect to the Brundtland definition creates tension for the sector and hinders their objective for positive change.

The literature definition above is silent on ‘assessment processes’, ‘outcomes’, and ‘quality of life’ as it pertains to human beings, animals, and plants [50], which is the bedrock of the WCED. We argue that, if sustainability is conceptualised in this way, it may encourage practitioners to jettison the structure, histories, and processes that have led to, and continually reinforced, inequality in global and local distribution of resources [7,50,93]. The term ‘sustainability’ not only bequeaths its meaning but its assessment, impact, and governance mechanism communicated through the outcome. The misconception posed by literature tends to pitch NGOs’ reporting merely towards achieving legitimacy. For example, defining sustainability on the basis of TBL which is anchored on people, planet and profit appear to be inherently faulty because of NGOs’ non-inclination to profit. As stated earlier, this definition is unbalanced and parochial in addressing the needs that it is meant to serve. Reporting to attract donations or because of pressure from stakeholders only points to the resource dependency nature of NGOs. In addition, [15] observed that effective collaboration is key in the pursuit of sustainable development goals and accountability because it equips NGOs with the power and influence needed to achieve these goals in society. This is also in line with the submission of [59] in his study of partnership between corporations and NGOs through sustainability

The definition of SR should be an embodiment of the mission and vision of NGOs, a reflection of impact, and a demonstration of the outcome, but this does not seem to be the case as seen in the discussion above. According to [14,107], SR and its indicators should be clearly defined, easy to interpret, and sensitive to the changes it is meant to address through a commitment to its mission [94,95]. It should be easy to assess over time and be practical [88,107]. To address the weaknesses vis-a-vis inconsistencies in the definition and reporting practices found in literature, it is suggested that SR be defined to reflect core issues that the Brundtland Report intended to address instead [50,88]. Resulting from the analysis of the definitions, these issues, otherwise known as the aim of the WCED, were missing or not succinctly encapsulated. The main features which underscore the very essence of the commission by the UN in 1987 (Brundtland Report) and which should inform the definition have not been well captured in literature.

The elements which include accountability mechanism, assessment and outcome, governance and impact, as well as the quality of life respond to call by [7,15,48] to reposition the understanding of sustainability in NGO to ensure it responds to global concerns, increase partnership and mutual responsibility that supports accountability, assessment, and impact. We argue that this will deepen the concept that links sustainability to quality of life through sustainable development practices. This makes NGOs different from private companies that tailor their SR based on investors whose interest is profit maximation that subsequently compels them to use different elements to measure and determine sustainability activities [108]. This is mainly because the narrative of sustainability portrayed by companies always differs from stakeholders’ interest in the company [109].

Our findings extend the work of [109] as well as [7] who notes that organisations will not be able to wholly “address the fundamental issues of sustainability” if it is not contextualised; especially when they “act alone”, “voluntarily”, or “based on economic motives”. The complexities or misinterpretations in the definition may not be unconnected to the different categorisations of NGOs. These are NGO orientation, level of operation, sectoral focus, and evaluative attributes which are capable of influencing NGOs’ understanding of sustainability practice. [7] noted that the way SR is defined in NGO is associated with the neoliberal projects and capable of neglecting the values of the NGO sectors as well as the larger civil society. It must be emphasised that sustainability is not an alternative to sustainable development but a means toward sustainable development. As such, it is not an end itself but a means to an end as highlighted earlier. It complements efforts toward the goals of sustainable development and which the Brundtland Report seeks to achieve. Hence, sustainability is “forward-looking and aims to secure resources for the future generation” [110] which adds to the quality of life. This article makes a contribution to theory and practice by introducing new elements that are expected to guide the definition of SR in NGOs that supports accountability and proper functioning of a circular economy and promotes sustainable development.

Findings show that the most dominant drivers of SR are stakeholder pressure and the desire to attract donors. This is consistent with the findings of [2,99] who assert that the level of reporting is significantly affected by the demands of the stakeholder group. [41] noted that NGOs continuously advance means to attract donors. NGOs’ need for resources makes them susceptible to the influence of more powerful actors. For instance, their resource needs pave the way for its reporting to be influenced, which subsequently erodes it of some influence/independence in line with the resource dependency theory [55,100,111]. Our findings reveal that external stakeholder groups such as the donors, government, competitors, and the community of beneficiaries exert substantial influence on the management of NGOs on their reporting. However, we note that the most common barrier identified in the literature is the voluntary nature of SR, accounting for 43% of the identified barriers (Table 3). This is consistent with the findings of [25]. We argue that a holistic implementation of SR, as well as other social performance measures, will not readily occur if it continues to be voluntary [7,25].

Therefore, we define SR as a process that accounts for the impact of the activities/project(s) of NGOs on the environment, society, or economy and that demonstrates governance and accountability mechanisms, aimed at ensuring continuity at the end of the initial funding period and geared towards improving the overall quality of life. When defined this way, SR addresses issues of accountability and positions organisations to better assess their environmental, social, economic, governance, and developmental practices in order to drive organisations’ strategies and values to a greater level of performance through their impact on society. It should be seen as a systematic operation scorecard that takes a balanced approach to social, environmental, economic, governance, and developmentally motivated behaviours of organisations towards improving the overall quality of life. It is the art of measuring, disclosing, and being accountable to internal and external stakeholders for organisational performance towards the goal of sustainable development [112]. Sustainability as a buzzword was initially conceived in response to stakeholder demands [4,98]; the onus is on developing a definition that espouses stakeholders’ interest and centres on improving the quality of lives in general. Literature shows that SR should ideally have a holistic approach in order to make real progress [15,33], further, an element of communication and assessment has become an important part of organisations’ contribution to sustainability [15,107].

Other than providing a platform for entrenching accountability and transparency as well as setting an example for others to follow, SR by NGOs can result in several benefits for both the NGOs and the society at large [25,101]. SR has the capacity to highlight hidden organisational values that might not be recognised through traditional reporting [17]. For instance, according to [17], an NGO that is dedicated to fighting human rights abuses and contribute to the advancement of democracy in a developing country is contributing to the quality of life and living standards in ways that traditional reporting may not be able to show. The protest in Liberia, Hong Kong, and more recently Nigeria, all calling for good governance and democratic government, is evidence that more can be done for the betterment of society. NGOs that harness the opportunities in highlighting their positive contributions in society and both account and report on such impacts in their operation, will enhance their own goodwill and ultimately improve their public perception, which in turn, could potentially increase their donor base [88,113].

Another important aspect of our findings is that different NGOs report on sustainability based on their activities rather than using a streamlined reporting system that supports uniformity and coherency. This could partly be due to a misunderstanding of the concept and lack of a legal framework for reporting on sustainability. For instance, our findings suggest that NGOs that were involved in environmental and civil campaigns [4,10,17] showed a better understanding of the SR reporting concept and were more influenced to publish SR. This review also shows that most development NGOs [37,50,88] define sustainability in line with the Brundtland Report. The nexus between for-profit SR and non-profit SR is that both are aimed at achieving sustainable development and are guided by GRI; this to an extent could explain the similarities in their reporting drivers and barriers. Although the GRI sector-specific guideline for non-profit reporting highlighted reporting goals which helped in the framing of the reporting elements above, it is silent on the definition specific to NGOs [14,114]. With respect to the significant erosion of trust in NGOs ranging from poor accountability to accusation of mission drift, the research paves the way for in-depth research that could be supplemented with empirical evidence on whether the disclosure of sustainability information is influenced by the self-interest of donors or by internal governance principles of NGOs. On the quest to ensure that accountability is not provided only to donors but to other stakeholders which would pave the way for a more robust dialogue on life-saving mechanisms of NGOs, research could explore what stakeholder group this accountability should be given to, the role of these stakeholders, and the influence they have on the sustainability outcome. While there is entirely a lack of research in certain areas such as culture and its influence on reporting criteria or other disputed managerial attitude/influence, SR is still seen as a concept that builds on accountability and transparency rather than a process of accountability and transparency itself. This is not surprising because SR has contested analytical importance and application, though with a strong positive resonance and outcome as noted by [7,48]. However, this outcome is difficult to evaluate, giving rise to a shift from a content analysis of published reports to a more exploratory approach through interviews and surveys. This suggests that there are abundant opportunities to tap into research in order to have a more informed and meaningful contribution to SR discussion.

Limitations of the Research

To reduce subjectivity and ensure coherence and reproducibility, we structurally and systematically adhered to the processes enumerated above. To achieve this, we minimised the possibility of prejudice in the entire process [115]; however, as is common with research of this nature, certain limitations are inherent, especially in the form of scope. For instance, the journals selected were only peer-reviewed journals; this is a limitation as books, conference papers, reports, comments, etc. of relevance to the topic were avoided. Though this affected the number of journal articles considered, peer-reviewed journals are generally known to be of high quality and devoid of bias; the blind review process enhances their credibility and acceptability as well. Another restriction was to review articles written in English only. While the reason for this is germane, articles of high quality and impact on the topic may have been avoided; again, this impacted on the volume and the diversity of articles consulted. However, the number of articles written in English far outweighs the number of articles written in other languages put together, so this will presumably have no impact on the quality of our work. The review was restricted to articles published within (2010–2020), and this is yet another limitation as we acknowledge that good articles relevant to the topic, published prior to 2010 and after 2020 may have been avoided in the process. Despite this, issues of sustainability have remained in the limelight within this period [74,99] and the volume of academic literature on the subject confirms this; based on this, we believe it would have very little or no effect on the overall quality of this paper. The use of key search terms, however broad, is another form of limitation. Another grey area was the exclusion of the Google Scholar database in our search. While this houses a large collection of publications in diverse fields of study, it heavily contains online repositories, publications by professional bodies as well as websites of all sorts and authors’ names and other information peculiar to authors [116]; as a result, this database was excluded [52] in order to eschew bias of any kind.

To guarantee that the research is reproducible and reliable, we ensured that two to three of the researchers went through a particular process (e.g., decision on the articles to be included and the analysis procedure) in order to ensure the same result if repeated and to achieve objectivity in our findings. The use of extensive keywords was to ensure a holistic search and increase generalisation of our findings; however, we do not entirely submit that our findings can be generalised beyond the reviewed articles [2,53,54].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.E.A. and M.E.V.; methodology, I.E.A.; software, I.E.A.; validation, I.E.A. and M.E.V.; formal analysis, I.E.A.; investigation, I.E.A.; resources, I.E.A.; data curation, I.E.A.; writing—original draft preparation, I.E.A.; writing—review and editing of the manuscript for important intellectual content and novelty, I.E.A., M.E.V., R.D., P.H.; visualization, I.E.A.; supervision, M.E.V., R.D., P.H.; project administration, I.E.A.; funding acquisition not applicable. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Crespy, T.C.; Miller, V.V. Sustainability reporting: A comparative study of NGOs and MNCs. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2011, 18, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, R.; Kühnen, M. Determinants of sustainability reporting: A review of results, trends, theory, and opportunities in an expanding field of research. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 59, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, C.; Milne, M.J.; Gramberg, B. The uptake of sustainability reporting in Australia. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 129, 445–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herremans, I.M.; Nazari, J.A.; Mahmoudian, F. Stakeholder relationships, engagement, and sustainability reporting. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 138, 417–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomini, D.; Rocca, L.; Carini, C.; Mazzoleni, M. Overcoming the barriers to the diffusion of sustainability reporting in Italian LGOs: Better stick or carrot? Sustainability 2018, 10, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goddard, A. Accountability and accounting in the NGO field comprising the UK and Africa—A Bordieusian analysis. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2020, 78, 102200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appe, S. Reflections on Sustainability and Resilience in the NGO Sector. Adm. Theory Prax. 2020, 41, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailey, J.; Salway, M. New routes to CSO sustainability: The strategic shift to social enterprise and social investment. Dev. Pract. 2016, 26, 580–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Argenti, A.P.; Saghabalyan, A. Reputation at risk: The social responsibility of NGOs. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2017, 20, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.K.K. Effective green alliances: An analysis of how environmental nongovernmental organizations affect corporate sustainability programs. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jones, R.K.; Mucha, L. Sustainability assessment and reporting for nonprofit organizations: Accountability for the public good. Voluntas 2014, 25, 1465–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira Neto, G.C.; Pinto, L.F.R.; Amorim, M.P.C.; Giannetti, B.F.; Ameida, C.M.V.B.D. A framework of actions for strong sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 196, 1629–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordery, C.; Rahman Belal, A.; Thomson, I. NGO accounting and accountability: Past, present and future. Account. Forum 2019, 43, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Y.H.; Napier, E.; Runfola, A.; Cavusgil, T.S. MNE-NGO Partnerships for Sustainability and Social Responsibility in the Global Fast-fashion Industry: A Loose-coupling Perspective. Int. Bus. Rev. 2020, 29, 101736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceesay, L.B. Exploring the Influence of NGOs in Corporate Sustainability Adoption: Institutional-Legitimacy Perspective. Jindal J. Bus. Res. 2020, 9, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuruppu, S.; Lodhia, S. Shaping accountability at an NGO: A Bourdieusian perspective. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2020, 33, 178–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fifka, M.; Kuhn, A.L.; Loza Adaui, C.R.L.; Stiglbauer, M. Promoting development in weak institutional environments: The understanding and transmission of sustainability by NGOs in Latin America. Voluntas 2016, 27, 1091–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, A.D.; Rees, J.C. Checks and balances? Leadership configurations and governance practices of NGOs in Chile. Empl. Relat. 2020, 42, 1159–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Unerman, J.; O’Dwyer, B. NGO accountability and sustainability issues in the changing global environment. Public Manag. Rev. 2010, 2, 475–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilt, C. External stakeholders’ perspectives on sustainability reporting. In Sustainability Accounting and Accountability; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, T. NGOs unite as sustainability surges. Women’s Wear Daily 2020, 21. Available online: https://wwd.com/business (accessed on 25 August 2021).

- O’Dwyer, B.; Boomsma, R. The co-construction of NGO accountability aligning imposed and felt accountability in NGO-funder accountability relationships. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2015, 28, 36–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumay, J.; Guthrie, J.; Farneti, F. Gri sustainability reporting guidelines for public and third sector organizations. Public Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 531–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delai, I.; Takahashi, S. Sustainability measurement system: A reference model proposal. Soc. Responsib. J. 2011, 7, 438–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.A.; Muir, S.; Hoque, Z. Measurement of sustainability performance in the public sector. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2014, 5, 46–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scobie, M.; Lee, B.; Smyth, S. Grounded accountability and Indigenous self-determination. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2020, 102198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feola, M.; Cragg, S.J.; Alwar, S.T.; Kwantes, C.T. Enhancing Foster Care Home NGO Sustainability via Social Franchising. Management 2020, 25, 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Klemes, J.J. Assessing and Measuring Environmental Impacts and Sustainability, 1st ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Walthan, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Brundtland, G.H. Our Common Future: Report of the world commission on environment and development. Accessed Feb 1987, 10, 1–300. [Google Scholar]

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Folks: The Tripple Bottom Line of 21st Century; Capstone: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, R. A re-evaluation of social, environmental and sustainability accounting. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2010, 1, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, J.; Henderson, S.A.R. Sustainability and the balanced scorecard: Integrating green measures into business reporting. Manag. Account. Q. 2011, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano, R.; Huisingh, D. Inter-linking issues and dimensions in sustainability reporting. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemmell, J.C.; Scott, E.M. Environmental regulation, sustainability and risk. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2013, 4, 120–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lion, H.; Donovan, J.D.; Bedggood, R.E. Environmental impact assessments from a business perspective: Extending knowledge and guiding business practice. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 117, 789–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]