Inclusion in Global Environmental Governance: Sustained Access, Engagement and Influence in Decisive Spaces

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Background

2.1. Participation and Inclusion of Non-State Actors in Global Governance

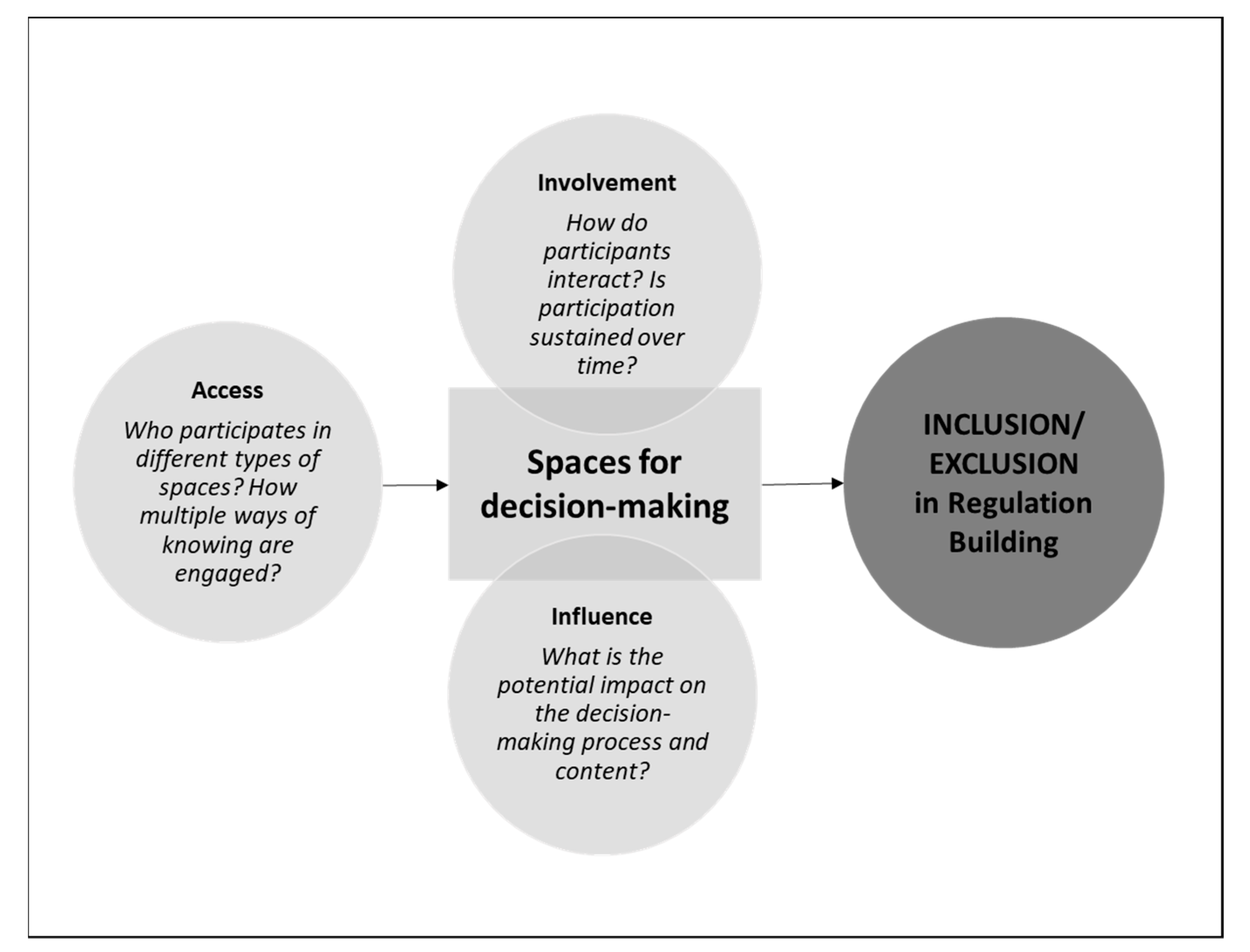

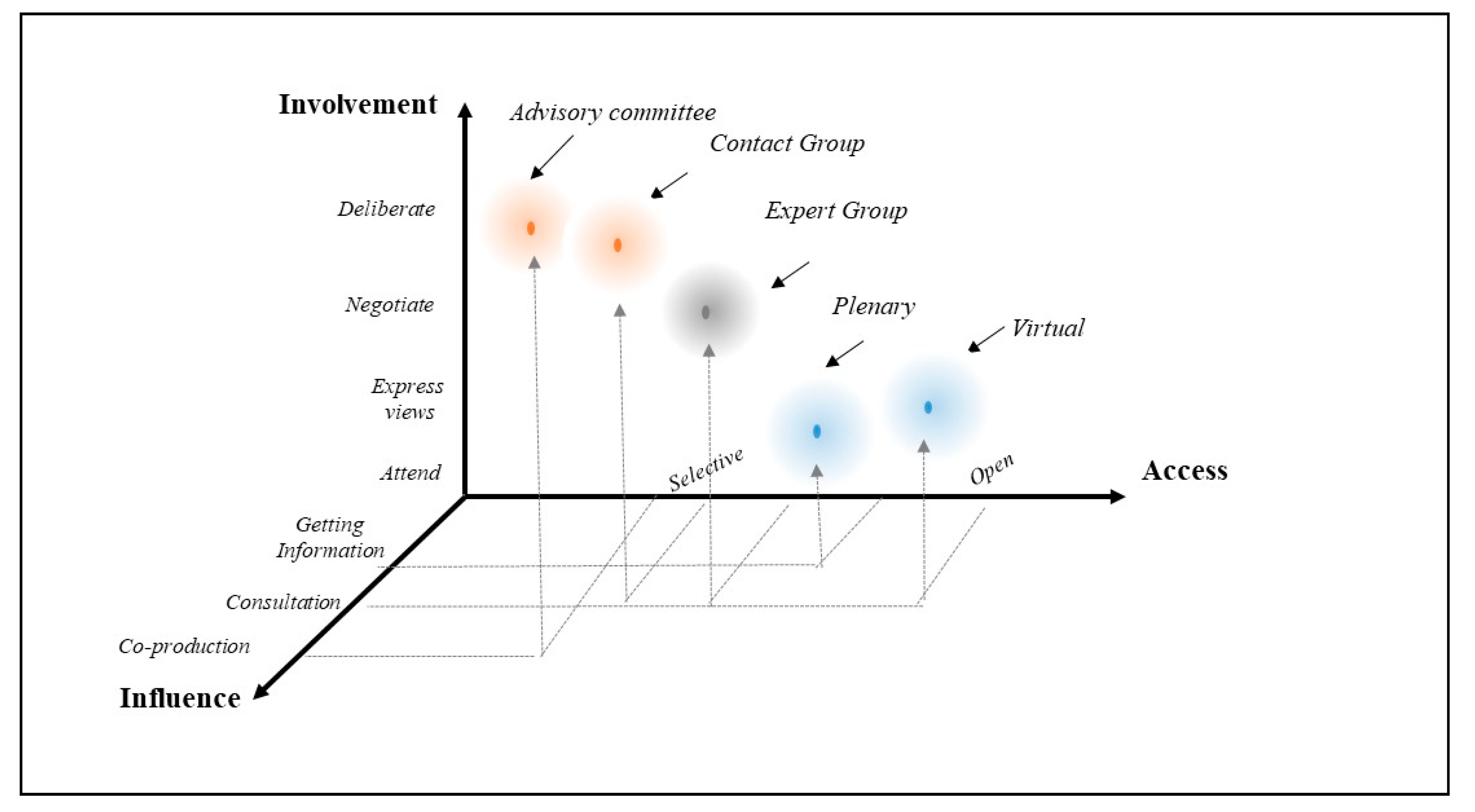

2.2. The Role of Spaces for Decision-Making

3. Methods

4. Results

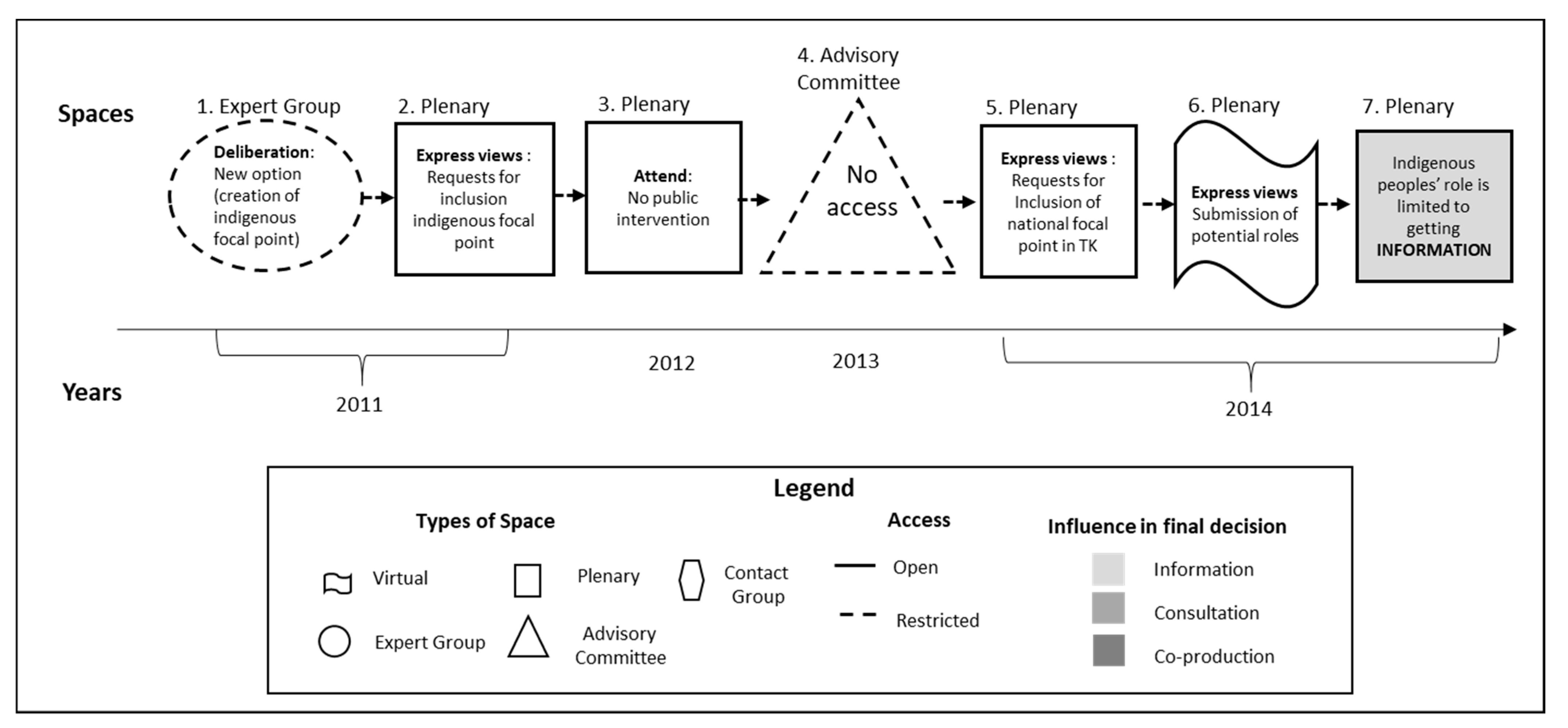

4.1. Decision-Making Process for Creating a Platform for Information Exchange (Issue 1)

“If we take into account the linguistic and cultural diversity of Indigenous peoples, we could create a mechanism that contemplates a greater representativeness”.(Interview 1, June 2011)

“In light of the significance that traditional knowledge has for Indigenous peoples…and the prominent place it occupies in the Nagoya Protocol, the treatment of this issue and the participation of Indigenous people must be given the same degree of importance in the Clearing House by … fully and effectively engaging representatives of local communities and their organizations”.[72] (p. 19)

4.1.1. Meeting Space 1—Expert Group Meeting on the ABS-CH (2011)

“This focal point would be a government official mandated to help communities transmit their relevant information, through instruments such as informed consent for access to traditional knowledge and models of contractual clauses for ABS contracts established with communities”.(Interview 4, June 2011)

“This article [ABS-CH] must be implemented in a manner that provides an opportunity for Indigenous peoples to provide the information which most accurately reflects their genetic resources that they hold as well as their associated traditional knowledge”.[73]

4.1.2. Meeting Space 2—Plenary of the First Intergovernmental Meeting (2011)

“The Métis National Council urged developing the process for submitting information with ILCs in an inclusive manner, respecting community protocols, confidentiality and MAT. She also noted that Indigenous focal points do not have authority to grant access to community resources, since this authority rests with the communities”.[74]

4.1.3. Meeting Space 3—Plenary of the Second Intergovernmental Meeting (2012)

“We have issues when they go and negotiate something key to us and we are not invited to participate. Despite all the advances in participation, remember, from our perspective we have to be fully included in the whole negotiation process”.(Interview ILC representative, 2013)

4.1.4. Meeting Space 4—Informal Advisory Committee on the ABS-CH (2013)

“Some points remained contentious… One expert from a developing country raised the question of the role of different stakeholders in the platform, in particular the possibility of Indigenous peoples to designate a competent authority that would publish their records at the clearing-house. The suggestion was not dismissed, but no other expert supported it. The compromise achieved between the experts was that the Secretariat could request submission of views of governments and stakeholders on the possible role for Indigenous Peoples on the platform before ICNP3”.(Field Observation Notes, 3 October 2013)

4.1.5. Meeting Space 5—Plenary of the Third Intergovernmental Meeting (2014)

4.1.6. Meeting Space 6—Virtual Submission of Views (2014)

“A national authority should work with an inter-cultural team that would include representatives from different Indigenous and local communities and have the financial and technical capacity to carry out its functions in a sustained and transparent manner; A competent authority should have ABS expertise and combine both western and indigenous perspectives, and should communicate with indigenous and local communities in a transparent and culturally appropriate manner, including in indigenous languages; A competent authority [for the ABS-CH] should be selected by the indigenous and local community’s authorities and be recognized by the local, regional and national authorities as well as the competent Ministry”.[77]

4.1.7. Meeting Space 7—Plenary of the Conference of the Parties (COP-MOP1) (2014)

“The IIFB draws your attention to Article 14 paragraph 3 (a) regarding the additional information on competent authorities of the IPLCs that will be provided to the Communication Exchange Mechanism. That is why we call on the states parties to consider the full and effective participation of IPLCs in the processes for the publication of their genetic resources and associated traditional knowledge in this Mechanism”.(IIFB Statement Read in Plenary COP-MOP1, 2014)

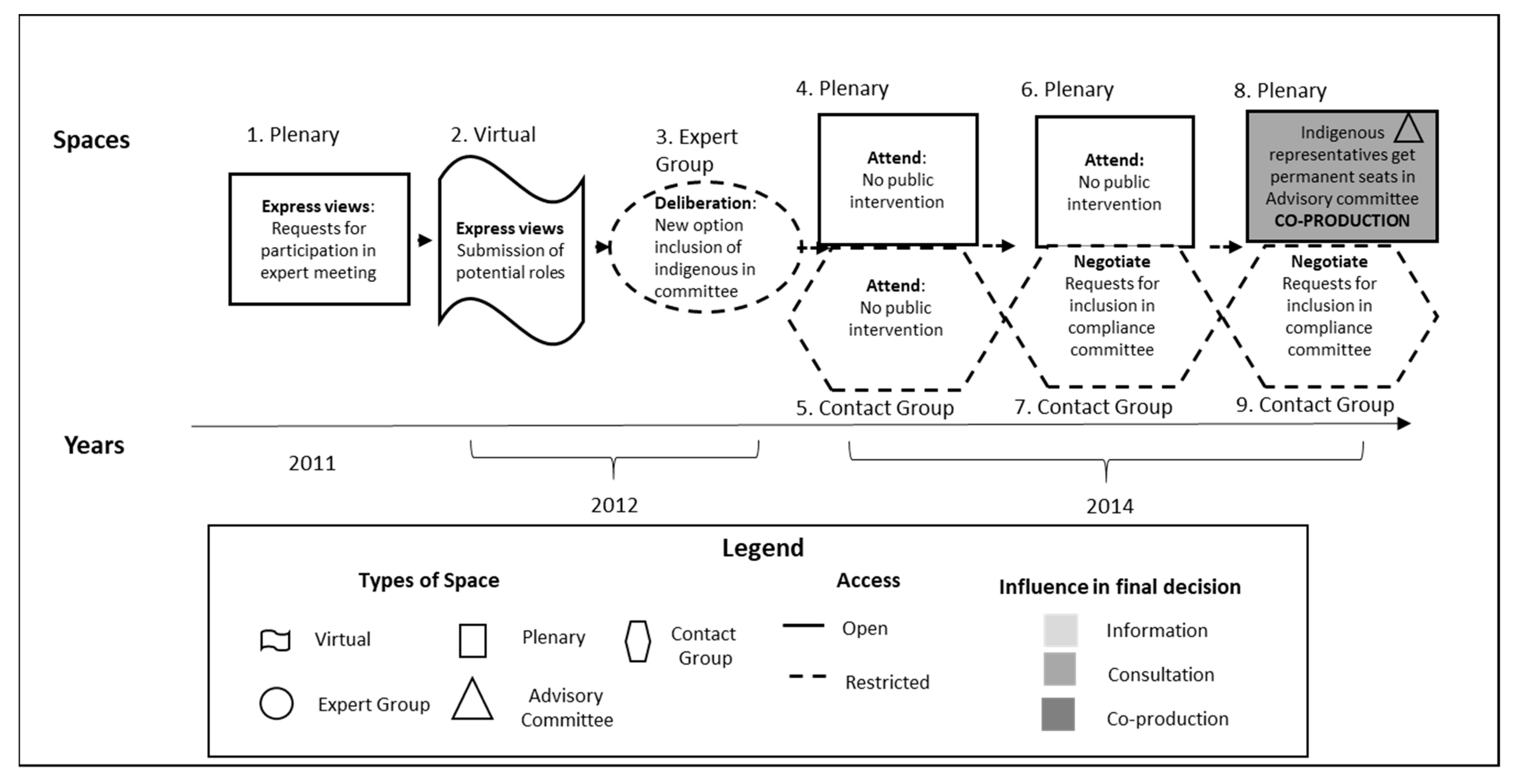

4.2. Decision-Making Process for Creating a Compliance Mechanism (Issue 2)

“Indigenous peoples, as rights-holders, often have more detailed and more specialized information regarding implementation challenges experienced ‘on the ground.’ They may also have innovative solutions to compliance issues based on experiences at the community, sub-national or national levels (…) Successful implementation of the Protocol is dependent upon full and effective participation by indigenous peoples and local community providers… A transparent and representative compliance mechanism will build confidence in the benefit sharing regime. Involving indigenous peoples in the operation of a compliance mechanism would likely address some of the ongoing concerns…The full and effective participation of indigenous peoples, as rights holders, must be respected in the development and implementation of the compliance mechanism”.[73] (pp. 3–7)

“Contact groups are the closest to the decision, and it’s in the contact groups that you’re making your arguments over the actual language and decision itself. And as we saw with the contact group on compliance, there are a lot of ideas that have been fed into that through previous meetings, like the expert meeting and the ICNP”.(Interview 50, Indigenous peoples’ Representative)

4.2.1. Meeting Space 1—Plenary of the First Intergovernmental Meeting (2011)

“The Indigenous Forum wants to insure full and effective participation of Indigenous peoples and local communities in all the discussions that take place on the matter of compliance, therefore we request that in the text of paragraph 3, the following be added after [where it reads] “convening an expert meeting,” ‘with the participation of Indigenous and Local Communities and the representation of distinct regions’”.(IIFB Statement read in ICNP1 plenary, 9 June 2011)

“The only way to ensure compliance to the Nagoya Protocol in the national level is through the respect of the rights of Indigenous peoples, by involving representatives in the negotiation of mutually agreed terms that consider our customary laws regarding traditional knowledge. We know ofcases where the rights of our communities were violated by users of traditional knowledge, and we need to help governments in preventing but also identifying those”.(Interview 10, Indigenous representative)

4.2.2. Meeting Space 2–Virtual Submission of Views (2012)

4.2.3. Meeting Space 3—Expert Group Meeting on Compliance (2012)

“There was a discussion about whether it was appropriate for indigenous and local communities to be able to nominate members to the committee, or serve on the committee and if so, whether as a full member or as an observer. The procedures for nominating representatives of indigenous and local communities were also discussed. A range of views were expressed, with some suggesting that given their prominence in the Protocol, indigenous and local communities should have representation on the committee”.[80]

4.2.4. Meeting Space 4—Contact Group of the Second Intergovernmental Meeting (2012)

“Although ILCs themselves were not vocal at this meeting due to the small number of representatives present, possibly resulting from a combination of visa issues and funding shortages, certain countries put forward a variety of possible avenues to ensure a community “voice” in the compliance mechanism. Options ranged from a community trigger of the procedure, to enabling community representatives to participate in the compliance committee as members or as observers, to the possibility for communities to submit information directly to the compliance committee, or the possibility for the committee to directly consult with relevant communities”.[75]

4.2.5. Meeting Space 5—Contact Group of the Third Intergovernmental Meeting (2014)

“Indigenous peoples and local communities believe the serious nature of the Compliance Committee requires assurance that any proposed structure of the committee is inclusive of Indigenous peoples and local communities and is determined in collaboration with ILCs”.(IIFB Statement read in Plenary at ICNP3 on Compliance Issue, page 2)

“The IIFB recommended: including in the compliance committee ILC representatives from each UN region; establishing regional ILC committees to advise and support ILC submissions to the compliance committee; and enable ILCs to make submissions to the compliance committee independently from national authorities”.[76]

“Governments gave us time to build narratives around the need for Indigenous expertise at the compliance committee. We received support from the governments of Ecuador and Mexico,longtime allies. However, Canadians were pretty much against our proposal because of concerns they have of the standing of Indigenous peoples in their internal political system”.(Interview 49, Indigenous Peoples representative)

4.2.6. Meeting Space 6—Contact Group in Conference of the Parties (COP-MOP1) (2014)

“Many delegates welcomed the agreement that the committee’s composition will include two permanent spots for ILC observers, who are self-nominated, and that issues brought to thecommittee can be decided by a majority vote. The COP/MOP also agreed that compliance procedures might be triggered by parties against other parties, by parties seeking assistance with compliance, and by the COP/MOP. ILCs may submit information for consideration by the compliance committee through the CBD Secretariat”.[78]

“ILCs had a major win in this meeting, because now they have a different status in comparison to other stakeholders. Because they are elected by COP, they hold a term and have earned continued involvement in compliance issues”.(Interview 51, Secretariat staff)

4.3. Comparing Varieties of Spaces: Integrating Access, Involvement, and Influence Dimensions of Inclusion

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bartley, T. Transnational governance and the re-centered state: Sustainability or legality? Regul. Gov. 2014, 8, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberlein, B.; Abbott, K.W.; Black, J.; Meidinger, E.; Wood, S. Transnational business governance interactions: Conceptualization and framework for analysis. Regul. Gov. 2014, 8, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Overdevest, C.; Zeitlin, J. Assembling an experimentalist regime: Transnational governance interactions in the forest sector. Regul. Gov. 2014, 8, 22–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toffel, M.W.; Short, J.L.; Ouellet, M. Codes in context: How states, markets, and civil society shape adherence to global labor standards. Regul. Gov. 2015, 9, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Witter, R.; Marion Suiseeya, K.R.; Gruby, R.L.; Hitchner, S.; Maclin, E.M.; Bourque, M.; Brosius, J.P. Moments of influence in global environmental governance. Environ. Politics 2015, 24, 894–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynberg, R.; Schroeder, D.; Chennells, R. Indigenous Peoples, Consent and Benefit Sharing: Lessons from the San-Hoodia Case; Spinger: Berlin, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Andonova, L.B.; Mitchell, R.B. The rescaling of global environmental politics. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2010, 35, 255–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Djelic, M.-L.; Sahlin-Andersson, K. Transnational Governance: Institutional Dynamics of Regulation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Steffek, J. Explaining cooperation between IGOs and NGOs–push factors, pull factors, and the policy cycle. Rev. Int. Stud. 2013, 39, 993–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlin, B.; Berlin, E.A. Community autonomy and the Maya ICBG project in Chiapas, Mexico: How a bioprospecting project that should have succeeded failed. Hum. Organ. 2004, 63, 472–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suiseeya, K.R.M. Negotiating the Nagoya Protocol: Indigenous demands for justice. Glob. Environ. Politics 2014, 14, 102–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.F. Transnational delegation in global environmental governance: When do non-state actors govern? Regul. Gov. 2018, 12, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, H. Agency in international climate negotiations: The case of indigenous peoples and avoided deforestation. Int. Environ. Agreem. Politics Law Econ. 2010, 10, 317–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.B. Who sustains whose development? Sustainable development and the reinvention of nature. Organ. Stud. 2003, 24, 143–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.B. A climate for change? Critical reflections on the Durban United Nations climate change conference. Organ. Stud. 2012, 33, 1761–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Escobar, A. Whose knowledge, whose nature? Biodiversity, conservation, and the political ecology of social movements. J. Political Ecol. 1998, 5, 53–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bexell, M.; Tallberg, J.; Uhlin, A. Democracy in global governance: The promises and pitfalls of transnational actors. Glob. Gov. A Rev. Multilater. Int. Organ. 2010, 16, 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.F. Private Authority on the Rise: A century of delegation in multilateral environmental agreements. In Transnational Actors in Global Governance: Patterns, Explanations and Implications; Jönsson, C., Tallberg, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 155–176. [Google Scholar]

- Mena, S.; Palazzo, G. Input and output legitimacy of multi-stakeholder initiatives. Bus. Ethics Q. 2012, 22, 527–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djelic, M.-L.; Quack, S. Transnational Communities: Shaping Global Economic Governance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, M.S.; Quick, K.S. Generating resources and energizing frameworks through inclusive public management. Int. Public Manag. J. 2009, 12, 137–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Feldman, M.S.; Khademian, A.M.; Quick, K.S. Ways of knowing, inclusive management, and promoting democratic engagement: Introduction to the special issue. Int. Public Manag. J. 2009, 12, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corson, C.; Campbell, L.M.; MacDonald, K.I. Capturing the personal in politics: Ethnographies of global environmental governance. Glob. Environ. Politics 2014, 14, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overdevest, C.; Zeitlin, J. Experimentalism in transnational forest governance: Implementing european union forest law enforcement, governance and trade (FLEGT) voluntary partnership agreements in Indonesia and Ghana. Regul. Gov. 2018, 12, 64–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suiseeya, K.R.M.; Caplow, S. In pursuit of procedural justice: Lessons from an analysis of 56 forest carbon project designs. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 968–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, A.C.A.; Quack, S. Trajectories of transnational mobilization for indigenous rights in Brazil. Rev. Adm. Empresas 2016, 56, 380–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reimerson, E. Between nature and culture: Exploring space for indigenous agency in the Convention on Biological Diversity. Environ. Politics 2013, 22, 992–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, D.F. Biodiversity, Access and Benefit-Sharing: Global Case Studies; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Avilés-Polanco, G.; Jefferson, D.J.; Almendarez-Hernández, M.A.; Beltrán-Morales, L.F. Factors that explain the utilization of the nagoya protocol framework for access and benefit sharing. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schroeder, D.; Chennells, R.; Louw, C.; Snyders, L.; Hodges, T. The Rooibos benefit sharing agreement–Breaking new ground with respect, honesty, fairness, and care. Camb. Q. Healthc. Ethics 2020, 29, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bavikatte, K.; Robinson, D.F. Towards a people’s history of the law: Biocultural jurisprudence and the Nagoya Protocol on access and benefit sharing. Law Env’t Dev. J. 2011, 7, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Orsini, A. The role of non-state actors in the Nagoya Protocol negotiations. In Global Governance of Genetic Resources; Oberthür, S., Rosendal, K., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 60–78. [Google Scholar]

- Langley, A.; Smallman, C.; Tsoukas, H.; Van de Ven, A.H. Process studies of change in organization and management: Unveiling temporality, activity, and flow. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hardy, C.; Maguire, S. Discourse, field-configuring events, and change in organizations and institutional fields: Narratives of DDT and the Stock-holm Convention. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 1365–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schüssler, E.; Rüling, C.C.; Wittneben, B.B. On melting summits: The limitations of field-configuring events as catalysts of change in transnational climate policy. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 140–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schroeder, H.; Lovell, H. The role of non-nation-state actors and side events in the international climate negotiations. Clim. Policy 2012, 12, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffek, J. Public accountability and the public sphere of international governance. Ethics Int. Aff. 2010, 24, 45–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallberg, J.; Sommerer, T.; Squatrito, T.; Jönsson, C. The Opening Up of International Organizations; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tallberg, J.; Sommerer, T.; Squatrito, T.; Jönsson, C. Explaining the transnational design of international organizations. Int. Organ. 2014, 741–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Djelic, M.-L. From the rule of law to the law of rules: The dynamics of transnational governance and their local impact. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 2011, 41, 35–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jessop, B. Globalization and the national state. In Paradigm Lost: State Theory Reconsidered, 1st ed.; Aronowitz, S., Bratsis, P., Eds.; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2002; pp. 185–220. [Google Scholar]

- Djelic, M.-L.; Quack, S. Globalization and business regulation. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2018, 44, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betsill, M.M.; Corell, E. NGO Diplomacy: The Influence of Nongovernmental Organizations in International Environmental Negotiations; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, D.R. COP-15 in Copenhagen: How the merging of movements left civil society out in the cold. Glob. Environ. Politics 2010, 10, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, D.R.; Green, J.F. Understanding disenfranchisement: Civil society and developing countries’ influence and participation in global governance for sustainable development. Glob. Environ. Politics 2004, 4, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, M. Information disclosure and environmental rights: The Aarhus Convention. Glob. Environ. Politics 2010, 10, 10–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hengevoss, A. Assessing the Impact of Nonprofit Organizations on Multi-Actor Global Governance Initiatives: The Case of the UN Global Compact. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffek, J. Deliberation and global governance. In The Oxford Handbook of International Political Theory; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 440–452. [Google Scholar]

- Young, M. Inclusion and Democracy; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Jessop, B. Revisiting the regulation approach: Critical reflections on the contradictions, dilemmas, fixes and crisis dynamics of growth regimes. Cap. Class 2013, 37, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, A. Varieties of participation in complex governance. Public Adm. Rev. 2006, 66, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanz, P.; Steffek, J. Global governance, participation and the public sphere. Gov. Oppos. 2004, 39, 314–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, D.L.; Newell, P.J. The Business of Global Environmental Governance; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl, J. The Indigenous Space and Marginalized Peoples in the United Nations; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hanegraaff, M.; Vergauwen, J.; Beyers, J. Should I stay or should I go? Explaining variation in nonstate actor advocacy over time in global governance. Governance 2020, 33, 287–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabel, C.F.; Zeitlin, J. Experimentalism in the EU: Common ground and persistent differences. Regul. Gov. 2012, 6, 410–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, A.G.; Palazzo, G. Toward a political conception of corporate responsibility: Business and society seen from a Habermasian perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 1096–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Quick, K.S.; Feldman, M.S. Distinguishing participation and inclusion. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2011, 31, 272–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). Traditional Knowledge and the Convention On Biological Diversity; CBD: Montreal, QC, Canada. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/abs/infokit/revised/web/factsheet-tk-en.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Dawson, N.M.; Mason, M.; Fisher, J.A.; Mwayafu, D.M.; Dhungana, H.; Schroeder, H.; Zeitoun, M. Norm entrepreneurs sidestep REDD+ in pursuit of just and sustainable forest governance. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schouten, G.; Leroy, P.; Glasbergen, P. On the deliberative capacity of private multi-stakeholder governance: The roundtables on responsible soy and sustainable palm oil. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 83, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depledge, J. The Organization of Global Negotiations: Constructing the Climate Change Regime; Routledge: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Falkner, R. A minilateral solution for global climate change? On bargaining efficiency, club benefits, and international legitimacy. Perspect. Politics 2016, 14, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mair, J.; Hehenberger, L. Front-stage and backstage convening: The transition from opposition to mutualistic coexistence in organizational philanthropy. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 1174–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zietsma, C.; Lawrence, T.B. Institutional work in the transformation of an organizational field: The interplay of boundary work and practice work. Adm. Sci. Q. 2010, 55, 189–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yin, R.K. Case study Research: Design and Methods; Sage publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar, G. Access to genetic resources and protection of traditional knowledge in the territories of indigenous peoples. Environ. Sci. Policy 2001, 4, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suiseeya, K.R.M.; Zanotti, L.; Haapala, K. Navigating the spaces between human rights and justice: Cultivating Indigenous representation in global environmental governance. J. Peasant. Stud. 2021, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallbott, L. Indigenous Peoples in UN REDD+ Negotiations: “Importing Power” and Lobbying for Rights through Discursive Interplay Management. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- International Indigenous Forum on Biodiversity. Available online: https://iifb-fiib.org/ (accessed on 28 November 2017).

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Graebner, M.E. Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amazon Network. Statement Submitted to the ICNP1. 2011. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/abs/doc/protocol/icnp-1/redcam-en.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Assembly of First Nations. Statement Submitted to the ICNP1. 2011. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/abs/doc/protocol/icnp-1/assembly-first-nations-en.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Earth Negotiations Bulletin (ENB). ICNP1 Summary Report. 5–10 June 2011, p. 5. Available online: https://enb.iisd.org/biodiv/icnp1/ (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Earth Negotiations Bulletin (ENB). ICNP2 Summary Report. 2–6 July 2012, pp. 7–15. Available online: https://enb.iisd.org/biodiv/icnp2/ (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Earth Negotiations Bulletin (ENB). ICNP3 Summary Report. 24–28 February 2014, pp. 7–15. Available online: https://enb.iisd.org/biodiv/icnp3/ (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). Report on Progress Made and Feedback Received in the Implementation of the Pilot Phase of the Access and Benefit-Sharing Clearing-House; CBD: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2014; pp. 9–10. [Google Scholar]

- Earth Negotiations Bulletin (ENB). Summary Report Pyeongchang Meetings of the CBD and Its Protocols. 6–17 October 2014, pp. 14–31. Available online: https://enb.iisd.org/events/cbd-cop-12/summary-report-6-17-october-2014 (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). Submissions to the Expert Meeting on Cooperative Procedures and Institutional Mechanisms to Promote Compliance with the Nagoya Protocol. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/abs/submissions-compliance/ (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). Final Report Expert Meeting on Compliance; CBD: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2012; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Ansell, C.; Miura, S. Can the power of platforms be harnessed for governance? Public Adm. Rev. 2020, 98, 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Diprose, R.; Kurniawan, N.I.; Macdonald, K. Transnational policy influence and the politics of legitimation. Governance 2019, 32, 223–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Aleman, P.; Sandilands, M. Building value at the top and the bottom of the global supply chain: MNC-NGO partnerships. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2008, 51, 24–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roome, N.; Wijen, F. Stakeholder power and organizational learning in corporate environmental management. Organ. Stud. 2006, 27, 235–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fa, J.E.; Watson, J.E.; Leiper, I.; Potapov, P.; Evans, T.D.; Burgess, N.D.; Molnár, Z.; Fernández-Llamazares, Á.; Duncan, T.; Wang, S. Importance of Indigenous Peoples’ lands for the conservation of Intact Forest Landscapes. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2020, 18, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, M.; Taylor, L.; Crease, R. Indigenous Environmental Justice within Marine Ecosystems: A Systematic Review of the Literature on Indigenous Peoples’ Involvement in Marine Governance and Management. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, R.; Whiteman, G.; Banerjee, B. Conflict and astroturfing in Niyamgiri: The importance of national advocacy networks in anti-corporate social movements. Organ. Stud. 2013, 34, 823–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Space | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Plenary |

|

| Contact groups |

|

| Virtual |

|

| Expert groups |

|

| Advisory committee |

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aguilar Delgado, N.; Perez-Aleman, P. Inclusion in Global Environmental Governance: Sustained Access, Engagement and Influence in Decisive Spaces. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10052. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810052

Aguilar Delgado N, Perez-Aleman P. Inclusion in Global Environmental Governance: Sustained Access, Engagement and Influence in Decisive Spaces. Sustainability. 2021; 13(18):10052. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810052

Chicago/Turabian StyleAguilar Delgado, Natalia, and Paola Perez-Aleman. 2021. "Inclusion in Global Environmental Governance: Sustained Access, Engagement and Influence in Decisive Spaces" Sustainability 13, no. 18: 10052. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810052

APA StyleAguilar Delgado, N., & Perez-Aleman, P. (2021). Inclusion in Global Environmental Governance: Sustained Access, Engagement and Influence in Decisive Spaces. Sustainability, 13(18), 10052. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810052