Abstract

This multi-disciplinary science and Indigenous knowledge assessment paper reviews over 20 years of research materials, oral histories and Indigenous views on climate change affecting Unalakleet, Alaska, USA and Norton Sound. It brings a historical review, statistical analysis, community-based observations and wisdom from Unalakleet Iñupiaq knowledge holders into a critical reading of the current state of climate change impacts in the region. Through this process, two keystone species, Pacific salmon and caribou, are explored as indicators of change to convey the significance of climate impacts. We rely on this historical context to analyse the root causes of the climate crisis as experienced in Alaska, and as a result we position Indigenous resurgence, restoration and wisdom as answers.

1. Introduction

“I was born free. I won’t die free. What happened to us?”—An Elder from Unalakleet, 20th Century.

Alaskan climate change in all of its context has not been thoroughly discussed as a socio-ecological whole. Studies of northern climate change and, consequently, the impacts on Indigenous people in Alaska and beyond have emerged in the past 20 years as a major research topic [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. Studies of Indigenous knowledge and concerns have also included sectoral approaches in the Bering Sea, such as around transport [11].

Our focus area is Norton Sound, within the Bering Sea, and more specifically the village of Unalakleet, Alaska. We, a Finnish human geographer and a non-Indigenous Alaska-based scientist, present a multi-disciplinary assessment of climate change from the focus of this location building on two decades of engagement. We explore questions that go beyond monitoring and observation to include an assessment of the meaning of climate change from various viewpoints and what are argued to be the root causes and implications of the present day and future changes. The article, therefore, includes a strong equity—and Indigenous rights—focus. We recognize all Indigenous communities do not agree on the degree of climate change or the causes and solutions.

The majority of present-day climate change and Indigenous knowledge studies operate from a uniform, geographically-fixed base of contemporary social and cultural locations. A challenging view is to take the Indigenous historical experience into account; this has also been called an “endemic approach” [12,13]. Iñupiaq knowledge holder Herbert O. Anungazuk [14] (p. 189) has called this the “unwritten law of the sea”: “The lifeways of the Iñupiaq people cover an entire spectrum, a spectrum so wide and profound that it continues to astound the Western mind.”

In this article we try to position climate change as observed, experienced and interpreted in the community into an Iñupiaq-tradition informed matrix that included Indigenous Nations self-governing over their lands and seas [12]. These Nations also decided on issues following their specific socio-cultural, political, cosmological and spiritual processes [14,15]. The traditional land uses and social institutions were built on an intimate understanding of nature and its cycles. Burch [16] (p. 40) points to the historical fact that “each of the Iñupiaq nations discussed both claimed and asserted dominion over a distinct territory having clearly defined border… When people crossed the border into another nation’s territory, they were either trespassers or guests, depending on the particular circumstances attending their passage.”

According to Ray [17,18] each of the distinct units had a “chief/’omelik’” who served as the leader of the kazgi, the community house where decisions and actions were taken. These chiefs were mostly male. The village with a kazgi was the central political location for a nation. Other villages would belong to the nearest autonomous kazgi or Nation with distinct borders. A central political-social method of maintaining power, social relations, trade and governance was the messenger feast in the villages [18] (p. 224). It also assisted in adaptations to change and disruptions.

Northwest Alaska was a homeland of several Iñupiaq Nations self-governing their assets and natural resources according to customary governance until the time the process of colonization began, first by Russia (beginning in the 1700s) and then subsequently the United States of America (from 1867 onwards). The loss of self-governance was sped up by the introduction of dependencies on firearms [19], cash economies and large epidemics [15,16,20,21,22,23] and political takeover of lands, resources, language and social spaces.

Pratt [24] (p. 105) has described that the Unalakleet region with the Iñupiaq, Yupiaq and the Athabascans provided an important exception to Burch’s understanding of Indigenous Nations. According to him, this was due to trading and that the groups “had a stable, friendly relationship and had friendly borders” as opposed to conflicts elsewhere in Alaska. Ray [17,20] also identified specific historical reasons for the Norton Sound region as an exception to the rule of the Nations and their territories.

Our work has been informed by and builds on Napoleon’s [15,21] Indigenous evaluation of the events that have transformed the Iñupiaq and Yupiaq self-governing nations into present day modern communities. According to him the colonial process, especially the internal loss of culture and society as a result of the “Great Death”, i.e., the epidemics, has not been understood to this day and manifests in the present day as a transference of post-traumatic stress of social ills and collapse of specific nation-based governance, culture, languages and social realities across Alaska.

We have chosen this approach (founded on [21]) to look at current climate change in greater depth and to view it in context as a historical and as an equity process in Alaska. We do not claim that we know a comprehensive view nor that the space allows for an exhaustive review of the situation in Unalakleet. Instead, our attempt is to position the events underway into the losses and partial resurgence experienced in Unalakleet. We conduct this in order to explore the root causes of current change by combining oral histories, written Indigenous knowledge statements, science and governmental reports.

2. Materials and Methods

We combine Iñupiaq knowledge, in oral histories and written statements, with the latest natural sciences view of climate change in Unalakleet and, subsequently, the Norton Sound and connected Bering Sea. In the studies of Alaska, there is a trend to include “observations” [5] of change from Indigenous co-researchers, but the deeper contexts and frames of knowledge, histories and cultures are often left out. Instead, Iñupiaq knowledge has been seen at best as Indigenous literature [22,25] or cultural production, but the narratives and statements by Indigenous Alaskans linking a historical and endemic approach have not often been included as a study of climate or ecological change. On the other hand, oral histories and communal lore have been of great importance at the community level [12].

Hykes-Steere [26] has called attention to the fact that the internal dimensions of the Iñupiaq are only slowly being discovered: “Our world is so completely different than most of you can imagine. A world without time because our world is timeless…. We are taught that you can live in a moment a whole lifetime and words are sacred.” With this realization, the understanding of Unalakleet, Norton Sound and the whole Bering Sea should be re-assessed from a new viewpoint and methodology.

More specifically, the Indigenous history and peoples of Unalakleet have been described, using an “endemic view” by Ticasuk in detail [27] (Ticasuk’s views have also been under critical review locally). Historic governmental reports on the early modernisation of Unalakleet [28] provide a demographic and analytical view of the post-World War II situation. Community-based oral history work between 2002 and 2019 ([19] and Snowchange Unalakleet Oral History Archives) contains the words and knowledge of our co-researchers, the people of Unalakleet and their voices from the first decades of the 21st century. This is also the period of intensifying climate change impacts in the region resulting in the present-day crisis on land and at sea.

Victoria Hykes-Steere (an Iñupiaq woman originally from Unalakleet, presently in Anchorage) shares her written statements from 2002 to 2020 [29,30] on climate change issues and their links to the history of injustice in Alaska. We also include written statements of the Kawerak Inc. regional tribal consortium [31] as well as Iñupiaq individuals from Alaska who have shared their views on climate change in public [6,32].

We use two species (Pacific salmon (Oncorhynchus sp.) and caribou (Rangifer tarandus)) as key socio-ecological species for the community. One of these indicators, Pacific salmon, transects between the ocean and the river ecosystem, i.e., they are anadromous. This is, in a way, symbolic for the shape and role of Indigenous knowledge as a fluid and connected method of knowing. We also include open-ended sections on weather change and Indigenous wisdom. We treat Indigenous knowledge (sometimes known as traditional knowledge, Iñupiaq knowledge, local-traditional knowledge, Indigenous wisdom and also ‘endemic knowledge’ [13]) and associated streams of information (oral histories, paintings and written statements) being of equal and independent value as a method of knowing.

The methods used include Indigenous evaluation [29], endemic ways of knowledge [13], oral history [33] and narrative analysis [34] to position the observations, views and Indigenous wisdom of climate change into a frame relative to Unalakleet. Secondly, we use community-based monitoring [35] as a vehicle to position and understand the issues from the materials.

These methods have been complemented with field visits during 2002–2019, community-based workshops to document and understand the Unalakleet climate change situation, literature reviews, place name analysis and youth engagement (2002–2019). All oral histories, interviews and workshops have been collected and conducted using the principles of free, prior and informed consent.

For the western scientific understanding of climate and ecological change in Unalakleet, we used a literature review and publicly available data sets from the region to position the speed and scope of change into a useful framework. Cartographic and satellite data interpretations, field visits during 2002–2019 and regional ecological monitoring of key indicators and species are also used. In the conclusion, we position the Indigenous knowledge and science trends on the two keystone species into a dialogue to point to potential divergences, disparities and commonalities followed by a final assessment using the long-term Indigenous knowledge of the situation.

3. Results

3.1. Historical Context

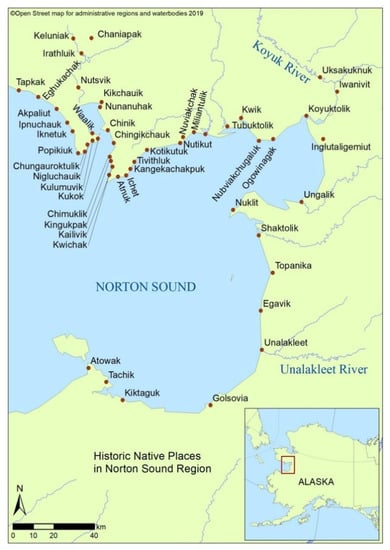

It is impossible to investigate the present-day experience of climate change without first reviewing the historical context of Indigenous peoples of Unalakleet as a tapestry of Alaska. Unalakleet is a village located on the Norton Sound at the mouth of the Unalakleet river in Alaska (Figure 1 provides a map of the Norton Sound region, with place names as described below). It is located approximately 630 km from Anchorage and is a fly-in community (https://kawerak.org/our-region/unalakleet/) (accessed on 1 December 2019). The earliest archaeological evidence from the present-day village site dates back to 200 BC (also see [32]). Emery, Redlin and Young [36] (p. 482) say that the site would have been used for “15,000” years but do not provide a more exact source for their data.

Figure 1.

Map of Norton Sound region.

According to Ray [20], place-name analysis is a method of understanding occupation and presence over long periods of time in Indigenous Alaska. On the Norton Sound, according to her, the Iñupiaq and Yupiaq systematized their travel and camp sites as well as dwelling sites on place names. Ray [20] (p. 256) and [16,24] point out that, today, most of the Indigenous place names have been lost as they ceased to be used for the most part in the end of the 1800s: “(place names) once held a tribal territory together, provided mnemonic guides for travel and utilisation of resources and forged a permanent and identifiable bond with the land.”

Pratt [24] identifies the community to have been a major historical node for pan-Indigenous trading and migrations. According to Pratt [24] (p. 94), the Indigenous peoples in the region at the time of the European contact were the Koyukon Athabascan and Unalit Yupiaq peoples. Some sources recall earlier Iñupiaq presence already in 1830s (Snowchange Unalakleet Oral History Archive 2019). Ray [20] also reports occasional Iñupiaq “travellers” down to the Kuskokwim river in the early 1800s. Until around 1800, Unalakleet was a major border of Iñupiaq and Yupiaq languages. After that, Ray [17,20] says that it became a trilingual community of Malemiut Iñupiaq, Kauwerak Iñupiaq and Yupiaq (see critical view of the Malemiut concept in [16]). This change was triggered by a loss of caribou in the Iñupiaq home areas further north and increasing trade [18,37]. Burch [23] places the overall crash of this Nulato Hills caribou herd (see below) between 1870 and 1900 (see critical assessments of his analysis in [38,39]). Ray [18,37] refers to this as a major economic revolution in the region. The destination of the increased trade was the Russian-established trading market of Anyui on the Kolyma river delta in Siberia in the Chukchi homeland [18].

Burch [16] (p. 319) offers a very important analysis of the arrival of what he calls a “new social system”. He writes that the combination of loss of caribou, small-pox, trade and other drivers all contributed to the establishment of the Iñupiaq presence on Norton Sound. According to him, the social structure of the Iñupiaq allowed strangers to join with a specific Nation. He says Unalakleet received the survivors of famine even from the Kivallinigmiut people [16] (p. 321).

The documented place names of Iñupiaq and Yupiaq origin on the sea coast around the community reflects the seasonal rounds of hunting, fishing and gathering (see [20] for a full list), including those listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Selected older Iñupiaq, Yupiaq, Unalit and Athabascan place names of the Unalakleet catchment area as in Pratt [24] (p. 112).

Challenging, in part, Ray [17,20] and other scholarship, Pratt [24] argues that the Unalakleet river catchment area and the upstream river have historically been Koyukon Athabascan-occupied, as reflected in the place name analysis. Burch [16] (p. 12) also adds to Ray’s analysis that there are names of individuals reflected in the Norton Sound place names. Toponyms such as Haatoghee’a Denh are evidence of the large use and occupancy by the Athabascans [24] (p. 100).

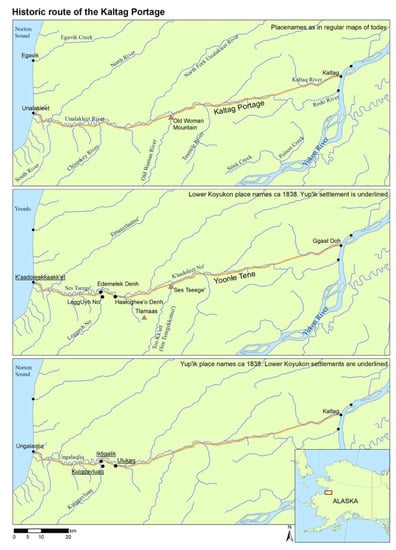

The village has been a significant pre-historical trade area between the Athabascan, Yupiaq, known as Unaligmiut (considered the “original inhabitants” of the community in pre-history), and “northern” Iñupiaq (also speaking Malemiut and other Iñupiaq dialects, such as Kauwerak) peoples in Norton Sound connected by overland route to the Yukon River in the East. This route is known as the Kaltag portage (see map in Figure 2) and positioned local nations into a geopolitically central role as mediators of trade up and down the Yukon River.

Figure 2.

Historic route of the Kaltag portage.

The place name Unalakleet has been defined as “From the South Side” (some sources earlier translated it as “Where the East Wind Blows”, but this is today considered inaccurate ([19,24]). Ray [20] also says “One river to the south, or where the south wind blows”). Ray [20] and Pratt [24] offer the historical evolution of the place name: From “Uliakagmiut/Ungalaklik/Unalaklik” (this referred specifically to the Yupiaq community south of the river mouth. The Iñupiaq had their settlement north of the river) into “Ulukagmiut” (in 1800s) into the present-day Unalakleet (these toponyms have also referred to the ethnic communities in place across time). Pratt [24] (p. 112) says that Ungalaqliq referred to “from where the south wind blows” amongst other meanings.

Ticasuk [27] (p. 29) says that the Kuvunmute Iñupiaq people arrived at Unalakleet from the north from the Kobuk River area. She [27] (p. 49) points also to the Yupiaq influence in the community associated with the proliferation of trade following the contact with the settlers (Russians) in the 1700s. Pratt [24] (p. 95) provides that the first contact happened in 1778 (while Ray [20] (p. 252) points out that King Island, Ukivuk, was reported by Daurkin in 1765). He says [24] (p. 95) that the first European to visit Unalakleet was Andrei Glazunov in 1833. Ray [37] and [16,23] report that the first firearms arrived in the region in 1819. Pratt [38] offers criticism of this theory and links these herds to a larger Western Arctic caribou herd (WAH), pointing that Burch’s assessment of the firearms was vague. According to them, the introduction of firearms may not be a valid argument in losses of caribou populations in the region. Instead, other reasons such as cyclical population dynamics may be at play. Mager [39] has also continued the assessment but comes close to [23] genetic evidence.

The earliest recorded notes from Unalakleet are from the Russian-American company who constructed a post there in 1830s. Ray [18] points to the number of ships associated with the search of the Franklin expedition that caused major social impacts in 1849–1853. In 1892–1898, reindeer herders were brought into the region to introduce this northern trade to Alaska [23] (p. 17). These herds dwindled after 1936 for the most part, with some exceptions such as in Stebbins [40].

Ticasuk [27] offers a view on the pre-contact and early-contact Unalakleet society as observed by the peoples themselves and “handed down” from the past using Iñupiaq knowledge transfer. She provides a view of the royalty, kinship and a description of the endemic [13] decision-making processes in the community. Her account describes the Iñupiaq traditional royalty from the region, including Alluyagnak I and II ([18] she spells them as Alluiyanuk) and Queen Masu. Ray [18] says that majority of the Iñupiaq population in Norton Sound is related to Alluiyanuk. Hykes-Steere [41] describes these royalties in her recent reflection: “Dorothy Jean Ray did field work in Unalakleet in the 1960s and stayed with my great-grandmother, my grandmother’s mom and our last traditional Queen. Her father was Chief Nashalook (see also [27])—the last one Unalakleet had. His two brothers, (the oldest) and Paniptchuk were co-Chiefs, but Nashalook, the youngest brother, was made Chief when he was 20 or 21. Their dad was Chief. There are five Iñupiaq languages in Unalakleet, so unlike most villages we were not all related.”

According to Ticasuk [27] (p. 27), the Norton Sound Iñupiaq practiced their seasonal rounds according to ecology and the species and food available. Freeze-up and ice-melt defined the uses of the marine and terrestrial areas for hunting, fishing, gathering, trading and other activities [27]. The authors of [20,28] point to the fact that, historically, the Unaligmiut had been living as far west as in Golovin Bay, influencing the linguistic situation there.

A major social change event was the arrival of the Reverend Axel E. Karlson (originally from Sweden) who became a significant advocate of Christianity in the village and in the region. He arrived into the Norton Sound Region in 1887 and from there on started to expand his missionary work [27] (p. 95). This has been summarized as follows: “On June 25, 1887, Evangelical Covenant missionary A.E. Karlson arrived in St. Michael. In St. Michael, he happened to meet Nashoalook of Unalakleet, who spoke some English and Russian. Nashoalook, a medicine man and the last traditional chief of Unalakleet, was one of five tall, dark brothers who had moved to Unalakleet from Malemiut country, which is east of Kotzebue. Nashoalook invited Karlson to Unalakleet, and travelled there on July 12, 1887. In Unalakleet, not all of the locals were as friendly to Karlson as Nashoalook was, and a plan was hatched by three men to kill Karlson. Upon learning of this murderous plan, Nashoalook hid Karlson in his home for three months until the angry men could be persuaded not to kill Karlson” [42].

Ticasuk [27] (p. 97) describes that there used to be a “kargii” (kazgi is the spelling cited in [17]) surrounded by sodhouses in the area, reflective of the Iñupiaq customary rule and governance. She points to a fact that many earlier residents of Unalakleet had “died” before the re-settlement was underway in the 1880s. Ray [20,28] confirms this and points to a small-pox epidemic of 1838–1839, which left the community with only “13 survivors”.

This indicates the massive role of the epidemics of the region [15,16]. According to Ray [18], subsequent epidemics included measles and pneumonia in 1900 and the 1918 influenza epidemic. She also refers to the 1830 tsunami that affected coastal villages. A major outside driver in the region was also the number of gold rushes between 1898 and 1900.

Ulukagmiut also entered into regional conflicts with the Athabascans, including the Nulato Massacre in 1846–1851 ([24] p. 97). However, at the time of the 1838 epidemic, there was an Iñupiaq settlement on the north side of the river (the one Karlson saw), which amalgamated the 13 survivors from the Unalit (Snowchange Unalakleet Oral History Archive 2019).

Ray [28] (pp. 150–151) says that the Iñupiaq arrival to the Unalakleet region was also driven by the accelerating status of the Russian fur trade, which was prominent between 1836 and 1868 ([24] p. 97). By establishing personal kinships in the region with the Unaligmiut, the Iñupiaq were able to establish their presence in the area (see also in [27] on the personal kinship relations of Norton Sound). Ray [28] (p. 151) says that the key period for co-existence of the Iñupiaq and the Unaligmiut happened around 1865–1867. The amalgamation process sped up with the missionary work by Karlson.

Karlson was involved also in the construction of the “new” village of Unalakleet [27]. The area had been used for a long time as an Indigenous trading and occupancy site, yet the 1887 events saw the fixing of the village site to its present location. At this time Russian was a common trading language in the area due to the history of the Russian-American company trading and settling since 1700s. In later years, English became dominant.

The question of land rights has persisted in Alaska beginning with the 1867 transfer officially to the US from Russia [29]. A range of legislation, including the Dawes Act and the Wheeler–Howard Act, advocated either for recognition of “Native lands” or extinguishment. A central driver of these political-legal actions was the question of how the lands of Alaska could be utilized. The people themselves were equally active early on. Already in 1912, the Alaska Native Brotherhood struggled for recognition of Indigenous rights. Between 1942 and 1946, Unalakleet was included in a group of seven reservations, similar to the mainland United States. Unalakleet was the smallest with a land base of only 870 acres [43] (p. 87).

In modern history, Alaska was established as a state in 1959. The twin drivers of unsettled Indigenous rights and the discovery of oil and gas as well as other resources led the U.S. Congress to pass the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) of 1971 (see critical views in [29,44] and supporting views in [43]). This Act transferred Indigenous lands and governance areas into ownership by regional and village for-profit corporations—a solution that has not been used elsewhere. The city of Unalakleet was incorporated in 1974 (https://kawerak.org/our-region/unalakleet/) (accessed on 15 January 2020).

According to Hykes-Steere [29] the ANSCA transformed the land governance away from the traditional governments into the hands of “western”-defined corporations. Hykes-Steere [29] (p. 384) says that “congress… forced (Indigenous hunters, fishers and gatherers) into the market economy and the 20th century, the largest land grab in U.S. history and a marvel of social engineering designed to destroy the social fabric of our communally-based societies.”

3.2. Climate Change

According to Indigenous observations from Unalakleet, climate change impacts began to emerge primarily during the post-ANSCA era. We call this period “modern Unalakleet”. Climate change impacts, as perceived by the people in the community, started in the early 1990s. Major visible climate change impacts as perceived locally include coastal erosion, sea level rise and storm surges. The community has been chosen as one of the most vulnerable in Alaska because of this by NOAA [45]. Emery, Redlin and Young [36] (p. 481) estimate that 86% of the Alaska Native villages in Alaska will face “destruction” because of these drivers.

Aronson [45] (p. 7) stresses the spirit of survival in the community. This has led the community to take a range of actions overall, including erosion monitoring with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, sales of uphill land lots to residents to have new housing areas, construction of a sea wall and wind power installations to diversify community energy sources.

We have chosen one marine and one terrestrial species of central importance to the Unalakeleet residents as keystone species (Pacific salmon and caribou). This allows for an ecosystem-crossing view and to position and discuss the community-based Indigenous observations from several co-researchers between 2002 and 2019, several of whom have passed on. We wished to allow a rigorous dialogue with scientific indicators of the same species to take place and, hence, chose only two species, a terrestrial and an anadramous example, even though, as is often said, Indigenous knowledge does not separate or uplift certain species over others. Two final categories refer to weather change and an open-ended space for “Indigenous wisdom” where the undefined free expression of Iñupiaq knowledge can be outlined.

Even this method of expressing observations remains limited. The space here does not allow for linguistic scaling, Indigenous evaluation [29] or a full oral history disclosure of the nuances and details of change. Our purpose is, however, to position observations into a twenty-year frame and meaning in order to offer a coherent view of change.

Table 2 lists key observations, an interpretation of meaning in the given context and the source material where the observation can be referenced for each indicator species listed. Brief summaries from the observations listed in the table are in the sections below.

Table 2.

Key observations, meaning and source material references for Pacific salmon and caribou.

3.2.1. Pacific Salmon (Various Oncorhynchus spp.)

Key summary: The authors of [6] (p. 127) describe the fish species important in the community (including Pacific herring, King salmon, Chum salmon, Pink salmon, Silver salmon and trout species), and how they are fished and used. Pacific salmon species are central for food security and culture. Major declines in numbers occurred between 1983 and the 2002–2007 period. After this, Silvers rebounded for a while, whilst King salmon numbers were very low until 2019 when they made a return. Pink salmon mass death events triggered widespread concern in 2019, alongside changing ocean and river conditions. Industrial harvests (by “foreign pirates”, pollock by-catch, major fisheries in the Alaska Peninsula and Aleutian Islands Management area and. to a much smaller extent, the local commercial fishery) affected the subsistence catch. Trout are increasingly affecting salmon smolts.

3.2.2. Caribou (Rangifer tarandus)

Key summary: Early crashes of caribou stocks in Northwest Alaska triggered a migration of some of the Iñupiaq further south [23]. In 1867 there were large numbers of caribou in Unalakleet. During the early 1900s, the caribou were not as plentiful, and reindeer introduced by Sámi herders in 1891 [51] eventually joined the caribou herds. Caribou were abundant and provided for the village during 1980–2000, but since then numbers have dwindled, and animals have moved further away from the village ([28] gives a base number of 200,000 caribou in the Bering Strait region, with 15,000 annually on average).

3.2.3. Weather

Table 3 shares key observations related to weather observations and changes, including references for the source material. The information includes how Elders and earlier generations could predict weather accurately, and some people could even influence the wind and weather, but those skills are being lost as a community. Snow amounts and storms have been observed to change significantly. The timing and process of break up and freeze up have also been affected in recent years. Continuing coastal erosion is a concern, as are algal blooms in the ocean. There is less sea ice, and it is thinner. Major storms and lack of sea ice have occurred more recently in 2010s.

Table 3.

Key observations related to weather and source material references (including summarized observations and direct quotes; direct quotes are indicated with quotation marks).

3.2.4. Indigenous Wisdom

Table 4 provides space for the open-ended sharing of Indigenous wisdom that occurred in interviews and materials. By highlighting these specific statements, we are pinpointing what constitutes as meaningful as perceived by Indigenous evaluation methods. In summary, climate change is observed to be caused by greed and loss of traditional Indigenous values. Survival and well-being in Unalakleet is understood to be deeply connected to the health of animals and fish and the environment. The “ownership” of Alaska was described to have been wrongly transferred to parties that are not managing the environment well. The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act has not delivered the promised rights or solved the crisis in the villages.

Table 4.

Open-ended Indigenous wisdom, including source material references.

3.3. “Children’s Voices”

Listening to the voices of the youth of a community provides an important perspective on the present and future and what it means for them to experience and adapt to the present changes. Mustonen and Mustonen [19] collected a range of oral histories from the youth of the early 2000s. In these materials, the presence of communal distribution of catches and the presence of a number of cultural practices, such as feeding the seal salt water after a hunt, are still prominent. Young boys recounted harvesting beluga whale with nets and the knowledge to cut the whale using Indigenous patterns.

Between 2008 and 2018, the school of Unalakleet and two schools in the Eurasian North, Selkie in Finland and Norya in Udmurtia, Russia, initiated a traditional knowledge education programme and exchanges. This revitalisation of educational and cultural aspects has included activities on the land, weather observation and prediction, painting and dancing, to name some examples.

In 2015, the children in Unalakleet school created animated stories about a “School of Dreams” (Available online: http://www.snowchange.org/2015/02/school-of-dreams-produced-animations-and-a-look-to-the-future-in-urals-bering-straight-and-boreal-finland/) (accessed on 14 February 2015). The topics of the animations were focused around a faith in a technological future, including Antigravity, Flying Books, Jet Pack, Robot Girl, Time Traveller and Village in a School [55].

In 2019, the third grade class in the Unalakleet school shared their visions of the future of Unalakleet through a painting exercise (Available online: http://www.snowchange.org/2020/02/children-of-unalakleet-alaska-paint-their-future-2020/) (accessed on 14 February 2020). Themes in the paintings incorporated aspects of observed climate change and adaptations, as well as village changes and desires. For example, students painted other families moving to the hills above town, a rising ocean, snow, warming temperatures, more trees in town, a water park and airplanes.

3.4. Science Results

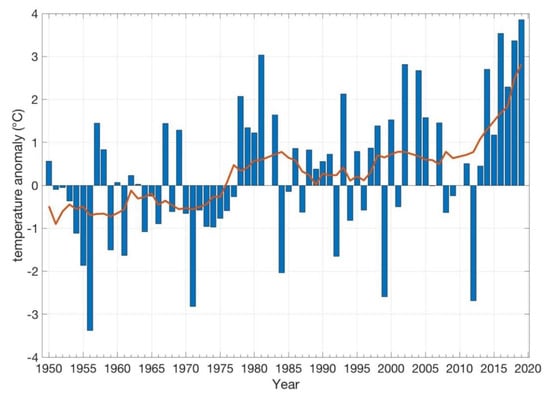

Information from western scientific methods indicate that the Arctic is undergoing a period of unprecedented change [56]. It is well established in the scientific literature that greenhouse gas emissions from the industrialized world and land use changes are causing far-reaching and accelerating change to the climate and ecosystems of the Circumpolar north. Temperature increases across Alaska vary greatly by season and location, with the fall and winter periods in the western and northern regions of the state experiencing the greatest temperature increase [57,58,59]. Figure 3 shows the trend in annual average surface air temperature at Unalakleet for the available record, from 1950 to 2019 ([60]; NOAA NCEI ISD dataset as described in [61]). There has been an approximately 2 °C change in the annual average surface air temperature in Unalakleet since 1950, based on a least-squares linear fit.

Figure 3.

Annual surface temperature trends at Unalakleet, AK, 1950–2019. Grey bars are annual mean atmospheric temperature anomalies at Unalakleet, AK, calculated relative to a base period 1961–1990. Air temperature data are from a meteorological station at Unalakleet, from the NOAA National Center for Environmental Information (NCEI) Integrated Surface Database (ISD), a quality-controlled global repository of surface meteorological observations from governmental and meteorological organizations worldwide [61]. The data were accessed through the IMIQ Data Portal [60]. The red line is a 10 year moving average.

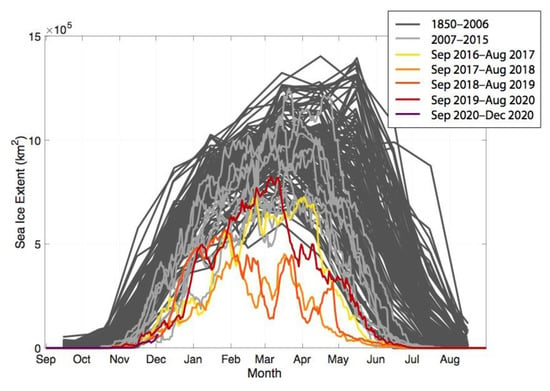

Seasonal sea ice in the Bering Sea is crucial for coastal communities, marine and terrestrial ecosystems and regional climate. The annual variation in sea ice extent between 1850 and 2020 in the Bering Sea is shown in Figure 4. The winters of 2017–2018 and 2018–2019 represent an unprecedented deviation from the over 160 year record of sea ice extent in the Bering Sea. The record low sea ice extent observed in the Bering Sea during these recent winters is an integral part of the massive ecosystem shifts underway in this region due to the importance of sea ice as a control on ocean temperature and by initiating primary production in spring through the provision of algae that forms under the ice in winter [62,63,64]. The conditions that contributed to ice loss during these years include unusually warm southerly winds during the winters that caused substantial ice retreat, delayed ice arrival in the Northern Bering Sea due to late freeze-up of the southern Chukchi Sea in 2017 and 2018 and warm ocean temperatures [65]. Work by Thoman et al. [66] indicates that the 2018 extreme low sea ice extent in the Bering Sea may become the mean level by the 2040s.

Figure 4.

Annual cycle of Bering Sea Ice Extent 1850–2020. Dark grey lines indicate data from the Historical Sea Ice Atlas, 1850–2007 [70]. Light grey (2007–2015), yellow (winter 2016–2017), light orange (winter 2017–2018), dark orange (winter 2018–2019), red (winter 2019–2020) and purple (through Dec 2020) lines indicate NSIDC MASIE-NH sea ice extent data (https://doi.org/10.7265/N5GT5K3K) (accessed on 14 February 2015). The [70] data provide the Bering Sea ice extent value on the 15th of each month, whereas the NSIDC MASIE-NH data provide a daily sea ice extent value.

Typically, shore-fast sea ice in Norton Sound dampens the impact of late fall and winter storms. The lack of sea ice combined with winter storms during the 2017–2018 and 2018–2019 winters resulted in coastline erosion, infrastructure damages and unprecedented winter flooding events in villages along the northern and western coasts of Alaska, including Unalakleet [59,67,68]. In other regions of coastal Northern Alaska, the lengthening sea ice free season is resulting in an extended fall storm season with more destructive waves and damage later in the year, including increased flooding and erosion [69].

Summer sea surface temperatures along Alaska’s west coast were 2.5 to 6 °C warmer than average during the summer of 2019 [58]. Historically, the thermal barrier that existed between the southeastern region of the Bering Sea and the Northern Bering Sea was an important division between the linked but separate ecosystems in these regions [64,71]. The location and extent of the “cold pool” (water temperature less than 2 °C) at the ocean bottom is primarily determined by the southern extent of sea ice during the preceding year and its melt-out date. This cold pool is a critical aspect of the ecosystem of the Northern Bering Sea, as it provides habitat and refuge for cold-tolerant species such as Arctic cod (Boreogadus saida) [72,73] and acts as a barrier for adult subarctic fishes such as walleye pollock (Gadus chalcogrammus) and Pacific cod (Gadus macrocephalus) [74,75].

The extent of the cold pool was substantially reduced in the summers of 2017–2019, and temperatures in the Northern Bering Sea near the seafloor have been above 0 °C in general for an increasing amount of time [64]. The loss of sea ice, lack of thermal barrier and warm ocean and atmospheric temperatures have triggered massive ecological shifts 2017–2019. Increases in Pacific cod, walleye pollock, and several flatfish species were observed in the Northern Bering Sea [76]. Work by Thorson et al. [72] demonstrates a northern shift and reduced area of the Arctic community assemblage (which includes Arctic cod and other species) between 2010 and 2018. Genetic analyses indicate that the increase observed in Pacific cod biomass in the Northern Bering Sea in 2017 was a result of northward migration from their historical range in the Southeastern Bering Sea during the anomalously warm summer conditions [77].

In addition to fish community assemblage and species range shifts as described above, ecosystem changes have reverberated elsewhere throughout land, ocean and air. Harmful algal species that are responsible for toxic algal blooms are expanding in the Arctic alongside warming ocean conditions [78,79]. Seabird surveys and monitoring demonstrated low seabird abundances at sea and low reproductive success, partially due to low forage fish abundance [63]. An increase in seabird die-off events in 2018 in the Northern Bering and Chukchi Seas continued through summer of 2019, with preliminary studies indicating starvation as the likely cause of death [80,81]. In 2019, NOAA declared an UME for three of the four Alaskan ice seal species in the Bering and Chukchi Seas (bearded (Erignathus barbatus), ringed (Pusa hispida) and spotted (Phoca largha) seals were affected; ribbon seals (Histriophoca fasciata) were not) [82].

3.4.1. Pacific Salmon

Pacific salmon species are experiencing various changes across Alaska. To the south, climate change and habitat loss threaten their distribution. While in the north, a warming Arctic has provided opportunity for range expansion of some species [83]. In the Norton Sound region, the size of chum salmon has been declining steadily since 2000, potentially impacted by factors such as a warming climate, changing ocean ecosystem and fisheries-induced evolution [84]. Juvenile pink salmon, measured as catch per unit effort during trawl surveys in the Northern Bering Sea, increased markedly in 2017 [64].

A major event was the high atmospheric and water temperatures in July 2019, which is the likely cause of a large death event in pre-spawned pink salmon in multiple river systems in the Norton Sound Region [31,85]. This event is of great concern for salmon species in the region, as the observed high temperatures are likely to become more frequent under future climate change.

3.4.2. Caribou

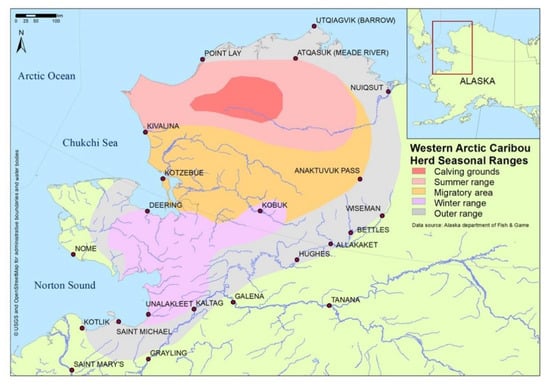

Specific to Northwest Alaska, Burch [16,23] outlines the existence of the now-disappeared Nulato Hills caribou herd (NHCH) that partly overlaps with today’s Western Arctic Herd (WAH; November to March overlap); there might have been seven specific herds before the 1800s in Northwest Alaska. Burch [23] says that after the population crash of the 1800s, only the WAH and Porcupine herds remained, with the NHCH disappearing by 1900. A herd can be identified based on their calving area. Burch [23], by documenting the changes on caribou in 1850–2000, identifies the dynamics of fluctuation and says that the key driver of the territorial dispersal is the size of the herd, with the calving area as the center of dispersal (see the seasonal herd dynamics in [23] and Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Seasonal ranges of the Western Arctic caribou herd (WAH).

The WAH calves in the Utuktok highlands [50,51]. According to scientists, the herd fluctuates on a decadal scale. Burch [23] (p. 67) says that the herd was at around 400,000–500,000 in 1840–1860; in his words, “immense herds” occupied and passed Unalakleet in 1867. There was a recent low of 75,000 animals in 1976 which then rebounded to the present 259,000 (peaking at 463,000 in 1996 and 493,000 in 2003, [50,51]). This also indicates that Unalakleet is at the southern edge of the herd, meaning a loss of caribou near the community if numbers go down ([23,50,51] see also continued and critical assessment of this model in [38,39]). Across their circumpolar range, caribou and reindeer herds have declined in response to factors related to climate warming and anthropogenic landscape changes [86,87].

The mixing of reindeer and caribou in the earlier parts of the 1900s was also a cause of changes [23]. Caribou behaviour has been puzzling both to local Iñupiaq reindeer herders and scientists in trying to determine why the WAH caribou use the Seward peninsula irregularly [51]. The author of [54] points to the knowledge that the loss of caribou cascades in the community, including lack of intergenerational knowledge sharing.

4. Discussion: Positioning Indigenous Knowledge and Wisdom with Science from Unalakleet

Western science demonstrates the main drivers of climate change to be the burning of fossil fuels by industrialized societies and land use changes [88]. Indigenous knowledge from community voices takes this understanding a step further: the messages of the changing ocean, lands and waters of Unalakleet are understood to be caused by greed and the industrial (mis) use of resources, especially oil and gas [19,49]. This link has been established by individuals [29,32,46] as well as numerous community participants [19,49].

The impacts of climate change have accelerated, especially the Bering Sea warming that is reflected in the lack of sea ice, health and numbers of animals and other key indicators of a sub-Arctic ecosystem that is now suffering from the lack of its key components. These processes manifest both in western science and Indigenous knowledge materials (Table 5). We recognize that the understanding of the “why” and “how” of climate change is not the same across all coastal communities in Alaska.

Table 5.

Summarizing Indigenous knowledge and western science related to changes in the two keystone species and observed weather.

Hykes-Steere [29] (on her criticism of the corporation models and see also [44]) says that a central value for the Iñupiaq traditional society was to shy away from greed. One of the remedies for the misuse and overuse of natural resources, therefore, might be to re-establish an Iñupiaq-based value and management system of the traditional kind that would mind the limits and value of these resources (see also [16]). Weaver Ivanoff already identified in the 1980s how the new layers of government were complex in terms of the relationship to the traditional governance of Unalakleet (in [44] p. 149).

Pointing towards this direction, Hykes-Steere [29] (p. 384) recounts her grandmother’s words stressing that each person is born with “gifts”. This points to the presence of an Indigenous sense of the cosmos and the world still relatively in place in the early 1900s. Later the grandmother, reflecting on her life experiences of the tumultuous 20th century, had said: “I was born free. I won’t die free. What happened to us?” ([29] p. 384).

5. Conclusions

By tracing the histories of Unalakleet, we have observed a place that has been continuously inhabited at least for thousands of years. There have been waves of abandonment such as the epidemics of the 1800s [24,28]. The area used for trading and settlement has welcomed many Indigenous Nations in the past, including the “original” Yupiaq Unaligmiut and “northern” Iñupiaq as well as other Yupiaq and Athabascans before the European settlement. The people had Indigenous self-governance and customary justice system of their lands, including royalty [27].

A tumultuous era starting in the 1830s introduced small-pox and other epidemics to the Unaligmiut and other peoples of the region, resulting in what Napoleon [15] has called the “Great Death”. The impact over generations of this massive tragedy has only in recent decades been discovered, as observed from within the cultures [15]. The disruption of endemic, Indigenous governance and sheer loss of populations allowed the United States to settle Alaska in a speedy manner, following the early Russian influence.

A central driver for the settlement of land rights was the desire at the US Federal level to secure Alaska oil and gas for industrial uses. Western science and Indigenous knowledge shared from the Norton Sound region agree that the burning of such fossil fuels is the root cause of climate change and, thus, the present-day collapse of animal, fish and bird populations as well as the major changes on land and out at sea.

This has led many of the Unalakleet knowledge holders to question whether survival is possible [19] at all in the worsening conditions and the present-day economic model, which has brought short term gains to some in the village but has fundamentally altered what has been known as the “community-based culture of Unalakleet” [29].

Martha Itta from Nuiqsut, further north in Alaska, expresses a similar view and is currently involved in a divestment process for her community in order to get away from the oil production and dependency [89]. Jerry Ivanoff [46] produced the following overall assessment: “When I was a little boy, we were the power that was. My community, as a tribe, we controlled what we did in our village, in our tribal area…. What happened to us, you know? We owned everything from zero to 200 miles and all the land that we can run around in our tribal area, our tribal jurisdiction. And if you cross my land, and you’re a […] Indian then we killed them. Or if we crossed their land and we were Eskimo on their land they killed us, you know. It was just territorial, tribal and Nation, not for money. But for resources, hunting on my land….They didn’t even know what we were doing you know, in terms of land ownership. We owned it all. In terms of the river and the rights to all the resources around it. If we took care of it, it was all ours, you know. Everything in our river valley was ours. If you go into our river system today, it’s all clean, clear and cold. It’s pristine.”

At the same time, the community members are determined to thrive and adapt, as Donna Erickson [40] summarized: “Despite all the climate changes, we move and change with the climate changes, try to adapt.” At the community level, a number of actions have been taken in Unalakleet to address climate change impacts, including those described in this article and in Aronson [45].

Hykes-Steere [29] provides a number of drastic measures as answers. She outlines a pathway to Indigenous re-territorialisation and a vehicle for survival under climate change [15]. According to her [29] (p. 392), Alaska should be formally listed as a territory under the United Nations. This would open the door to a future decolonisation process. According to her analysis, the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971 is a unilateral Act and does not extinguish the prior existing claims of the Indigenous Alaskans.

Berger [44] is in alignment and calls for self-determination and the advancement of the Tribal governments of Alaska as a vehicle to correct the perceived mistakes of ANCSA. Napoleon [15] outlines the pathway for the social transformation of the Alaska Indigenous societies. According to him, a positive path for the future can be secured if the past “Great Death” is finally acknowledged. Then, the pathologies and the enduring cross-generational impacts and social ills should be reflected on as the reason for them is finally clear. Then, Napoleon [15] concludes that the Indigenous Alaskans can go on having undergone a decolonial self-reflection and acknowledgement for the past to build a new future; this time on their own terms.

Combined with a decolonisation process at the legal-political level, Hykes-Steere [29] points to allowing the climate change drivers to be addressed according to Iñupiaq values and knowledge, resulting in a new pathway of survival. This view is also reflected in a statement by Ivanoff [32]: “Though the Earth changes, it is still giving. Providing. Nurturing. Inuqtaq [a small boy in 2018] will still learn respect for what gives life. I hope the rest of the world quickly adapts and also respects the Earth–as we have for millenniums and will continue to do so” [32].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.M.; methodology, T.M. and B.V.D.; validation, T.M. and B.V.D.; formal analysis, T.M. and B.V.D.; investigation, T.M. and B.V.D.; resources, T.M. and B.V.D.; data curation, T.M. and B.V.D.; writing—original draft preparation, T.M. and B.V.D.; writing—review and editing, T.M. and B.V.D.; visualization, T.M. and B.V.D.; supervision, T.M.; project administration, T.M. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was internally funded by the Snowchange Cooperative.

Informed Consent Statement

This project adheres to the principles of Free, Prior and Informed Consent of Indigenous peoples.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available climate data sets were used in this study. These sources include the IMIQ hydroclimate Database and Portal at http://imiq-map.gina.alaska.edu/ (accessed on 1 December 2020) (Unalakleet surface temperature data); the Historical Sea Ice Atlas at https://nsidc.org/data/g10010/ (accessed on 1 December 2020) (1850–2007 Bering Sea ice extent; doi:10.7265/jj4s-tq79); and the National Snow and Ice Data Center MASIE-NH sea ice extent data at https://doi.org/10.7265/N5GT5K3K/ (accessed on 1 December 2020) (2007–2020 Bering Sea ice extent). Oral histories are available through sources referenced in the test, and through the Snowchange Oral History Archives by request only. Snowchange Cooperative follows a number of guidelines regarding Oral Histories and Indigenous Knowledge materials, including: Free, Prior, Informed Consent; GIDA CARE principles (https://www.gida-global.org/care/ (accessed on 1 December 2020)); and the Ottawa Indigenous Knowledge Principles (https://www.arcticpeoples.com/knowledge#indigenous-knowledge/ (accessed on 1 December 2020)). Not all of the materials in the Snowchange Oral History Archives are available publicly, though they can be made available upon request in most cases.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Kaisu Mustonen, Victoria Hykes-Steere, Nancy Persons, Bethany Fernstrom, teachers at the Unalakleet schools (Bering Strait School District), and the residents of Unalakleet for their contributions and help over the two decades of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- CAFF. Arctic Biodiversity Assessment; CAFF: Akureyri, Islanda, 2013; Available online: https://www.caff.is/assessment-series/233-arctic-biodiversity-assessment-2013 (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- ACIA. Arctic Climate Impact Assessment Overview Report; Arctic Council. ACIA Overview Report; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020; p. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, G.L.; Coyle, K.O.; Eisner, L.B.; Farley, E.V.; Heintz, R.A.; Mueter, F.; Napp, J.M.; Overland, J.E.; Ressler, P.H.; Salo, S.; et al. Climate impacts on eastern Bering Sea foodwebs: A synthesis of new data and an assessment of the Oscillating Control Hypothesis. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2011, 68, 1230–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Whiting, A.; Griffith, D.; Jewett, S.; Clough, L.; Ambrose, W.; Johnson, J. Combining Iñupiaq and Scientific Knowledge: Ecology in Northern Kotzebue Sound, Alaska; Alaska Sea Grant College Program, University of Alaska Fairbanks: Fairbanks, AK, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Huntington, H.P.; Braem, N.M.; Brown, C.L.; Hunn, E.; Krieg, T.M.; Lestenkof, P.; Noongwook, G.; Sepez, J.; Sigler, M.F.; Wiese, F.K.; et al. Local and traditional knowledge regarding the Bering Sea ecosystem: Selected results from five indigenous communities. Deep Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 2013, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond-Yakoubian, B.; Raymond-Yakoubian, J. “Always Taught Not to Waste”: Traditional Knowledge and Norton Sound/Bering Strait Salmon Populations; Kawerak, Inc.: Nome, AK, USA, 2015; Available online: https://kawerak.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/TK-of-Salmon-Final-Report.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Raymond-Yakoubian, J.; Raymond-Yakoubian, B.; Moncrieff, C. The incorporation of traditional knowledge into Alaska federal fisheries management. Mar. Policy 2017, 78, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meredith, M.; Sommerkorn, M.; Cassotta, S.; Derksen, C.; Ekaykin, A.; Hollowed, A.; Kovinas, G.; Mackintosh, A.; Melbourne-Thomas, J.; Muelbert, M.M.C.; et al. Polar Regions. In IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate; Portner, H., Roberts, D.C., Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E., Mintenbeck, K., Nicolai, M., Eds.; University of Alaska Fairbanks: Fairbanks, AK, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Crate, S.; Cheung, W.; Glavovic, B.; Harper, S.; Jacot Des Combes, H.; Ell Kanayuk, M.; Orlove, B.; Petrasek MacDonald, J.; Prakash, A.; Rice, J.; et al. Cross-Chapter Box 4: Indigenous Knowledge and Local Knowledge in Ocean and Cryosphere Change. In IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate; Portner, H.O., Roberts, D.C., Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E., Mintenbeck, K., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jeff Birchall, S.; Bonnett, N. Thinning sea ice and thawing permafrost: Climate change adaptation planning in Nome, Alaska. Environ. Hazards 2020, 19, 152–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntington, H.P.; Daniel, R.; Hartsig, A.; Harun, K.; Heiman, M.; Meehan, R.; Noongwook, G.; Pearson, L.; Prior-Parks, M.; Robards, M.; et al. Vessels, risks, and rules: Planning for safe shipping in Bering Strait. Mar. Policy 2015, 51, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apassingok, A. Lore of St. Lawrence Island: Echoes of Our Eskimo Elders; Bering Strait School District: Unalakleet, AK, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Mustonen, T. Endemic time-spaces of Finland: Aquatic regimes. Fennia 2014, 192, 120–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anungazuk, H. An Unwritten Law of the Sea. In Words of the Real People: Alaska Native Literature in Transition; Fienup-Riordan, A., Kaplan, L., Eds.; UAF Press: Fairbanks, AK, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-1-60223-004-0. [Google Scholar]

- Napoleon, H. Yuuyaraq: The Way of the Human Being; Madsen, E., Ed.; Alaska Native Knowledge Network: Fairbanks, AK, USA, 1996; ISBN 978-1877962219. [Google Scholar]

- Burch, E. The Iñupiaq Eskimo Nations of Northwest; University of Alaska Press: Fairbanks, AK, USA, 1998; ISBN 0-912006-95-1. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, D.J. Land Tenure and Polity of the Bering Strait Eskimos. J. West. 1967, 3, 371–395. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, D.J. Ethnohistory in the Arctic: The Bering Strait Eskimo; Limestone Press: Kingston, ON, Canada, 1983; ISBN 9780919642980. [Google Scholar]

- Mustonen, T.; Mustonen, K. It Has Been in Our Blood for Years and Years That We Are Salmon Fishermen: A Book of Oral History from Unalakleet, AK, USA; Snowchange Cooperative: Kontiolahti, Finland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, D.J. Eskimo place-names in bering strait and vicinity. Names 1971, 19, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napoleon, H. Yuuraraaq: The Way of the Human Being. In The Alaska Native Reader: History, Culture, Politics; Williams, M., Ed.; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, M. The Alaska Native Reader: History, Culture, Politics; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0822344803. [Google Scholar]

- Burch, E. Caribou Herds of Northwest. Alaska, 1850–2000; University of Alaska Press: Fairbanks, AK, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, K.L. Reconstructing 19th-century Eskimo-Athabascan boundaries in the Unalakleet River drainage. Arctic Anthropol. 2012, 49, 94–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fienup-Riordan, A.; Kaplan, L. Words of the Real People: Alaska Native Literature in Transition; University of Alaska Press: Fairbanks, AK, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-1602230057. [Google Scholar]

- Hykes-Steere, V. We Used to Sing: An Arctic Elegy; Animation film, 2011. Available online: https://vimeo.com/19500715 (accessed on 10 January 2020).

- Ticasuk (Emily Ivanoff Brown). The Roots of Ticasuk: An Eskimo Woman’s Family Story; Alaska Northwest Books: Portland, OR, USA, 1981; ISBN 978-0882401171. [Google Scholar]

- Alaska Natives and the Land.; Federal Field Committee for Development Planning in Alaska; Federal Field Committee: Washington, DC, USA, 1968.

- Hykes-Steere, V. Interpreting the Journey: Where Words, Stories Formed. In Indigenous Pathways into Social Research: Voices of a New Generation; Mertens, D., Cram, F., Bagele, C., Eds.; Left Coast Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1598746969. [Google Scholar]

- Hykes-Steere, V. Narratives on Climate Change 2002–2019. In Snowchange Unalakleet Archives; Snowchange Cooperative: Kontiolahti, Finland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kawerak Inc. Climate Change Letter to Senate Indian Affairs Committee. Available online: https://kawerak.org/climate-change-letter-to-senate-indian-affairs-committee/ (accessed on 2 October 2019).

- Ivanoff, L. The Bearded Seal My Son May Never Hunt; New York Times: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald, J. The Arctic Sky: Inuit Astronomy, Star Lore, and Legend; Nunavut Research Institute: Iqaluit, NU, Canada, 2000; ISBN 978-0888544278. [Google Scholar]

- Cortazzi, M. Narrative Analysis in Ethnography. In Handbook of Ethnography; Atkinson, P., Coffey, A., Delamont, S., Lofland, L., Lofland, J., Eds.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2001; pp. 384–394. ISBN 9780761958246. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, N.; Alessa, L.; Behe, C.; Danielsen, F.; Gearheard, S.; Gofman-Wallingford, V.; Kliskey, A.; Krümmel, E.M.; Lynch, A.; Mustonen, T.; et al. The contributions of Community-Based monitoring and traditional knowledge to Arctic observing networks: Reflections on the state of the field. Arctic 2015, 68, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Emery, M.; Redlin, M.; Young, W. Native Leadership and Adaptation to Climate Change. In Environmental Leadership: A Reference Handbook; Gallagher, D., Ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, D.J. Early Maritime Trade with the Eskimo of Bering Strait and the Introduction of Firearms. Arctic Anthropol. 1975, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, K.L.; Ganley, M.; Slaughter, D.C. New Perspectives on the Late Nineteenth-Century Caribou Crash in Western Alaska. In Arctic Crashes: People and Animals in the Changing North; Krupnik, I., Crowell, A., Eds.; Smithsonian Scholarly Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mager, K.H. Ghosts of the Caribou Herds Past: Evaluating Historical Caribou Crashes in Alaska Using Genetics. In Arctic Crashes: People and Animals in the Changing North; Krupnik, I., Crowell, A., Eds.; Smithsonian Scholarly Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson, D. Oral History Interview, 17th October 2019. In Snowchange Unalakleet Archives; Snowchange Cooperative: Kontiolahti, Finland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hykes-Steere, V. Snowchange Unalakleet Archives; Unpublished manuscript; Snowchange Cooperative: Kontiolahti, Finland, 15 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bering Straits Native Corporation. Historical Spotlight: Nashoalook and Karlson. The Agluktuk: Winter/Spring 2016. 2016, p. 2. Available online: https://beringstraits.com/historical-spotlight-covenant-high-school/ (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- Arnold, R. Alaska Native Land Claims; Alaska Native Foundation: Anchorage, AK, USA, 1976; ISBN B0006CVEIE. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, T. Village Journey: The Report of the Alaska Native Review Commission; Inuit Circumpolar Council: Utqiaġvik, AK, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Aronson, R. Adapting to Climate Change in Unalakleet, Alaska. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Washington, Washington, DC, USA, February 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanoff, J. Oral History Interview, 18th October 2019. In Snowchange Unalakleet Archives; Snowchange Cooperative: Kontiolahti, Finland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- ICC Alaska. Bering Strait Regional Food Security Workshop: How to Assess Food Security from an Inuuit Perspective: Building a Conceptual Framework on How to Assess Food Security in the Alaskan Arctic; Inuit Circumpolar Council: Anchorage, AK, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hovey, D. Warmer waters investigated as cause of pink salmon die-off in Norton Sound Region. Available online: https://www.adn.com/alaska-news/rural-alaska/2019/07/12/warmer-waters-investigated-as-cause-of-pink-salmon-die-off-in-norton-sound-region/ (accessed on 13 July 2019).

- Van Dam, B. Oral History Notes from Community Documentation, October 2019. In Snowchange Unalakleet Archives; Snowchange Cooperative: Kontiolahti, Finland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Joly, K. History, Purpose and Status of Caribou Movements in Northwest Alaska. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Christopher-Sergeant/publication/325768480_Future_Challenges_for_Salmon_and_the_Freshwater_Ecosystems_of_Southeast_Alaska/links/5b22e5de0f7e9b0e374800fc/Future-Challenges-for-Salmon-and-the-Freshwater-Ecosystems-of-Southeast-Alaska.pdf#page=51 (accessed on 13 July 2019).

- Rattenbury, K. Reindeer herding, Weather and Environmental Change on the Seward Peninsula, Alaska. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, AK, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, J. Jewell’s Hunt; Provider Films. 2019. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_pz88CumPp4 (accessed on 1 October 2019).

- Hykes-Steere, V. Snowchange Unalakleet Archives; Unpublished Manuscript; Snowchange Cooperative: Kontiolahti, Finland, 20 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Alaska Inuit Food Security Conceptual Framework: How to Assess the Arctic from an Inuit Perspective Report; Inuit Circumpolar Council—Alaska, 2015. Available online: http://iccalaska.org (accessed on 10 December 2019).

- Mustonen, T. Selkien Perinteestä 7; Snowchange Cooperative: Kontiolahti, Finland, 2015; Available online: http://www.snowchange.org (accessed on 1 December 2019).

- Box, J.E.; Colgan, W.T.; Christensen, T.R.; Schmidt, N.M.; Lund, M.; Parmentier, F.J.W.; Brown, R.; Bhatt, U.S.; Euskirchen, E.S.; Romanovsky, V.E.; et al. Key indicators of Arctic climate change: 1971–2017. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 045010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markon, C.; Gray, S.; Berman, M.; Eerkes-Medrano, L.; Hennessy, T.; Huntington, H.; Littell, J.; McCammon, M.; Thoman, R.; Trainor, S. Alaska. In Impacts, Risks, and Adaptation in the United States: Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume II; Reidmiller, D.R., Avery, C.W., Easterling, D.R., Kunkel, K.E., Lewis, K.L., Maycock, T.K., Stewart, B.C., Eds.; U.S. Global Change Research Program: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; pp. 1185–1241. [Google Scholar]

- Thoman, R.; Walsh, J.E. Alaska’s Changing Environment: Documenting Alaska’s Physical and Biological Changes Through Observations; International Arctic Research Center: Fairbanks, AK, USA; University of Alaska: Fairbanks, AK, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, J.E.; Brettschneider, B. Attribution of recent warming in Alaska. Polar Sci. 2019, 21, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherry, J.; Jacobs, A.; Heinrichs, T.; Fisher, W.; Delamere, J.; Haase, C.; Martin, P.; Bradley, J.; Jenkins, J.; Grunblatt, J.; et al. Imiq Hydroclimate Database at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. Available online: http://arcticlcc.org/projects/imiq/ (accessed on 21 January 2021).

- Lott, J.N.; Vose, R.S.; Del Greco, S.A.; Ross, T.R.; Worley, S.; Comeaux, J.L. The integrated surface database: Partnerships and progress. In Proceedings of the 24th Conference on Interactive Information Processing Systems for Meteorology, Oceanography, and Hydrology, New Orleans, LA, USA, 20–24 January 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Stabeno, P.J.; Kachel, N.B.; Moore, S.E.; Napp, J.M.; Sigler, M.; Yamaguchi, A.; Zerbini, A.N. Comparison of warm and cold years on the southeastern Bering Sea shelf and some implications for the ecosystem. Deep Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 2012, 65, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy-Anderson, J.T.; Stabeno, P.; Andrews, A.G.; Cieciel, K.; Deary, A.; Farley, E.; Fugate, C.; Harpold, C.; Heintz, R.; Kimmel, D.; et al. Responses of the Northern Bering Sea and Southeastern Bering Sea Pelagic Ecosystems Following Record-Breaking Low Winter Sea Ice. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2019, 46, 9833–9842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huntington, H.P.; Danielson, S.L.; Wiese, F.K.; Baker, M.; Boveng, P.; Citta, J.J.; De Robertis, A.; Dickson, D.M.S.; Farley, E.; George, J.C.; et al. Evidence suggests potential transformation of the Pacific Arctic ecosystem is underway. Nat. Clim. Chang 2020, 10, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stabeno, P.J.; Thoman, R.L.; Wood, K. Recent warming in the Bering Sea and its impact on the ecosystem. In Arctic Report Card 2019; Richter-Menge, J., Druckenmiller, M.L., Jeffries, M., Eds.; NOAA: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Thoman, R.L.; Bhatt, U.S.; Bieniek, P.A.; Brettschneider, B.R.; Brubaker, M.; Danielson, S.L.; Labe, Z.; Lader, R.; Meier, W.N.; Sheffield, G.; et al. The record low Bering sea ice extent in 2018: Context, impacts, and an assessment of the role of anthropogenic climate change. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2020, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hovey, D. Sea ice almost gone in Norton Sound; Conditions “uncannily similar” to last March. Available online: https://www.knom.org/wp/blog/2019/03/01/sea-ice-almost-gone-in-norton-sound-conditions-similar-to-last-march/ (accessed on 2 March 2019).

- Shallenberger, K. Winter Storms Flood Houses in Nunapitchuk and Kotlik; Alaska Public Media: Anchorage, AK, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Z.; Freeman, P.T.; Field, C.B.; Mach, K.J. Reduced sea ice protection period increases storm exposure in Kivalina, Alaska. Arct. Sci. 2018, 4, 525–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walsh, J.E.; Chapman, W.L.; Fetterer, F.; Stewart, S. Gridded Monthly Sea Ice Extent and Concentration, 1850 Onward, Version 2. Available online: https://nsidc.org/data/g10010 (accessed on 3 December 2019).

- Sheffield, G.; Hauser, D.; Thoman, R. Rapid Change: 2019 in Northwest Alaska’s Oceans and Impacts to Ecosystems and People. Available online: https://uaf-accap.org/event/rapid-change-2019-in-northwest-alaskas-oceans-and-impacts-to-ecosystems-and-people/ (accessed on 3 December 2019).

- Thorson, J.T.; Fossheim, M.; Mueter, F.J.; Olson, E.; Lauth, R.R.; Primicerio, R.; Husson, B.; Marsh, J.; Dolgov, A.; Zador, S.G. Comparison of near-bottom fish densities show rapid community and population shifts in Bering and Barents Seas. In Arctic Report Card 2019; Richter-Menge, J., Druckenmiller, M.L., Jeffries, M., Eds.; NOAA: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, J.M.; Mueter, F.J. Influences of temperature, predators, and competitors on polar cod (Boreogadus saida) at the southern margin of their distribution. Polar Biol. 2020, 43, 995–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldt, J.L.; Buckley, T.W.; Rooper, C.N.; Aydin, K. Factors influencing cannibalism and abundance of walleye pollock (Theragra chalcogramma) on the eastern Bering Sea shelf, 1982–2006. Fish. Bull. 2012, 110, 293–306. [Google Scholar]

- Ciannelli, L.; Bailey, K.M. Landscape dynamics and resulting species interactions: The cod-capelin system in the southeastern Bering Sea. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2005, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, D.E.; Lauth, R.R. Bottom trawl surveys in the northern Bering Sea indicate recent shifts in the distribution of marine species. Polar Biol. 2019, 42, 407–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spies, I.; Gruenthal, K.M.; Drinan, D.P.; Hollowed, A.B.; Stevenson, D.E.; Tarpey, C.M.; Hauser, L. Genetic evidence of a northward range expansion in the eastern Bering Sea stock of Pacific cod. Evol. Appl. 2020, 13, 362–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alaska Sea Grant. 2018/2019 Bering Strait/Chukchi Sea: Alexandrium Algae, Saxitoxin, and Clams. 2019. Available online: https://seagrant.uaf.edu/bookstore/pubs/MAB-75.html (accessed on 15 January 2020).

- Anderson, D.M.; Richlen, M.L.; Lefebvre, K.A. Harmful Algal Blooms in the Arctic. In Arctic Report Card; NOAA: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Siddon, E.; Zador, S. Ecosystem Status Report 2018: Eastern Bering Sea; NOAA Fisheries, 2018. Available online: https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/resource/data/2018-status-eastern-bering-sea-ecosystem (accessed on 9 May 2019).

- US Fish and Wildlife Service 2019 Alaska Seabird Die-off Fact Sheet 508C. Available online: https://www.nps.gov/subjects/aknatureandscience/upload/9Sep2019-Die-Off-USFWS-Factsheet-508C-revised-29Aug.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2020).

- NOAA. Fisheries Diseased Ice Seals: Unusual Mortality Events for Ice Seals in the Bering and Chukchi Seas. Available online: https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/alaska/marine-life-distress/2018-2021-ice-seal-unusual-mortality-event-alaska (accessed on 10 January 2020).

- Nielsen, J.L.; Ruggerone, G.T.; Zimmerman, C.E. Adaptive strategies and life history characteristics in a warming climate: Salmon in the Arctic? Environ. Biol. Fishes 2013, 96, 1187–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State of Alaska Salmon and People (SASAP). The Declining Size and Age of Salmon, Norton Sound Region. Available online: https://alaskasalmonandpeople.org/topics/the-declining-size-and-age-of-salmon/ (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Norton Sound Economic Development Corporation (NSEDC). 2019 Norton Sound Pink Salmon Die Off Event Likely Linked to Temperature. Available online: https://www.nsedc.com/norton-sound-pink-salmon-die-off-event-likely-linked-to-temperature/ (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Vors, L.S.; Boyce, M.S. Global declines of caribou and reindeer. Glob. Change Biol. 2009, 15, 2626–2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CARMA Western Arctic Caribou Herd. Available online: https://carma.caff.is/herds/538-carma/herds/626-western-arctic. (accessed on 3 February 2020).

- NASA. Global Climate Change: Vital Signsof the Planet. In Facts: The Causes of Climate Change. Available online: https://climate.nasa.gov/causes/ (accessed on 5 January 2020).

- Eilperin, J. Alaska Climate Change: Facing Catastrophe, This Town Can’t Quit Big Oil; Washington Post: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).