A Model for Sustainable Tourism Development of Hot Spring Destinations Following Poverty Alleviation: Understanding the Tourists’ Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Hot Spring Tourism and Sustainable Development

2.2. Theoretical Framework

2.3. Environmental Cognition

2.4. Hot Spring Experience and Food Experience

2.5. Attitude toward Culture Landscape

2.6. Revisit Intention

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Measurement and Pretest

3.3. Formal Data Collection

4. Results

4.1. Sample Profile

4.2. Measurement Model Testing

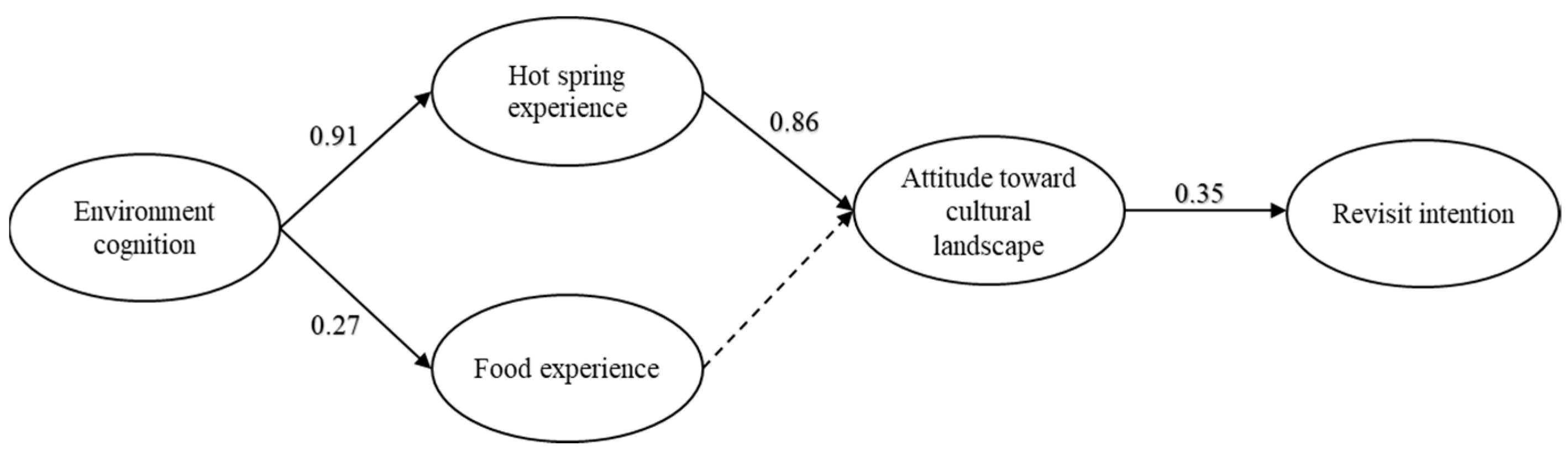

4.3. Structural Model Testing

5. Conclusions and Discussion

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Managerial Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Folgado-Fernández, J.A.; Di-Clemente, E.; Hernández-Mogollón, J.M.; Campón-Cerro, A.M. Water tourism: A new strategy for the sustainable management of water-based ecosystems and landscapes in Extremadura (Spain). Land 2019, 8, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, C. Sustainable tourism as an adaptive paradigm. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 24, 850–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Oyola, M.; Blancas, F.J.; González, M.; Caballero, R. Sustainable tourism indicators as planning tools in cultural destinations. Ecol. Indic. 2012, 18, 659–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richins, H. Environmental, cultural, economic and socio-community sustainability: A framework for sustainable tourism in resort destinations. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2009, 11, 785–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.W. Sustainable tourism: A state-of-the-art review. Tour. Geogr. 1999, 1, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, G. Is ecotourism sustainable? Environ. Manag. 1997, 21, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blancas, F.J.; González, M.; Lozano-Oyola, M.; Pérez, F. The assessment of sustainable tourism: Application to Spanish coastal destinations. Ecol. Indic. 2010, 10, 484–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grilli, G.; Tyllianakis, E.; Luisetti, T.; Ferrini, S.; Turner, R.K. Prospective tourist preferences for sustainable tourism development in Small Island Developing States. Tour. Manag. 2021, 82, 104178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalic, T. Concpetualising overtourism: A sustainability approach. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 84, 103025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP); World Tourism Organization (WTO). Making Tourism More Sustainable: A Guide for Policy Makers; UNEP: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Seki, A.; Brooke, E.H. Japanese Spa: A Guide to Japan’s Finest Ryokan and Onsen; Tuttl: Boston, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Karlovy Vary Official Tourist Website. 2021. Available online: https://www.karlovyvary.cz/en/what-treated-karlovy-vary (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- Clark-Kennedy, J.; Cohen, M. Indulgence or therapy? Exploring the characteristics, motivations and experiences of hot springs bathers in Victoria, Australia. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 22, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.H. Effects of cuisine experience, psychological well-being, and self-health perception on the revisit intention of hot springs tourists. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2014, 38, 243–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Fu, Y.; Li, J. The effect of on-site experience and place attachment on loyalty: Evidence from Chinese tourists in a hot-spring resort. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2019, 20, 75–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pessot, E.; Spoladore, D.; Zangiacomi, A.; Sacco, M. Natural resources in health tourism: A systematic literature review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Chen, J.; Hu, B. Authenticity, quality, and loyalty: Local food and sustainable tourism experience. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heung, V.C.; Kucukusta, D. Wellness tourism in China: Resources, development and marketing. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2013, 15, 346–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sthapit, E.; Coudounaris, D.N.; Björk, P. Extending the memorable tourism experience construct: An investigation of memories of local food experiences. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2019, 19, 333–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, S.; Wang, N. Towards a structural model of the tourist experience: An illustration from food experiences in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hare, D. Interpreting the cultural landscape for tourism development. Urban Des. Int. 1997, 2, 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauer, C.O. The Morphology of Landscape; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1925; Volume 2, pp. 19–54. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, G.; Raymond, C. The relationship between place attachment and landscape values: Toward mapping place attachment. Appl. Geogr. 2007, 27, 89–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, R.; Ollenburg, C.; Zhong, L. Cultural landscape in Mongolian tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2008, 35, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hitchner, S.; Schelhas, J.; Dwivedi, P. Safe havens: The intersection of family, religion, and community in black cultural landscapes of the southeastern United States. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 214, 104136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, A.; Beeton, R.J.; Pearson, L. Sustainable tourism: An overview of the concept and its position in relation to conceptualisations of tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2002, 10, 475–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Sanz, J.M.; Penelas-Leguía, A.; Gutiérrez-Rodríguez, P.; Cuesta-Valiño, P. Sustainable Development and Consumer Behavior in Rural Tourism—The Importance of Image and Loyalty for Host Communities. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). Tourism and Poverty Alleviation; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). 2017. Available online: https://webunwto.s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/imported_images/47283/iy2017_discussion_paper_executive_summary_en.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- Boluk, K.A.; Cavaliere, C.T.; Higgins-Desbiolles, F. A critical framework for interrogating the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals 2030 agenda in tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 847–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Ritchie, J.B. Tourism and poverty alleviation: An integrative research framework. Curr. Issues Tour. 2007, 10, 119–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Gan, C.; Chen, L.; Voda, M. Poor Residents’ perceptions of the impacts of tourism on poverty alleviation: From the perspective of multidimensional poverty. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, D.; Xu, H.; Chung, Y. Perceived impacts of the poverty alleviation tourism policy on the poor in China. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 41, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.P. Research on the basic components of hot spring tourism. Tour. Trib. 2006, 21, 5962. [Google Scholar]

- Mi, C.; Chen, Y.; Cheng, C.-S.; Uwanyirigira, J.L.; Lin, C.-T. Exploring the determinants of hot spring tourism customer satisfaction: Causal relationships analysis Using ISM. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-H. Determinants of revisit intention to a hot springs destination: Evidence from Taiwan. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2013, 18, 183–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, A.D.; Brownlee, M.T.; Hallo, J.C. Changes in visitors’ environmental focus during an appreciative recreation experience. J. Leis. Res. 2012, 44, 179–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations (UN). 2015. Available online: https://www.undp.org/sustainable-development-goals (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- Manwa, H.; Manwa, F. Poverty alleviation through pro-poor tourism: The role of Botswana forest reserves. Sustainability 2014, 6, 5697–5713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Dec. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodside, A.G.; Lysonski, S. A general model of traveler destination choice. J. Travel Res. 1989, 27, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.; Acevedo-Duque, A.; Müller, S.; Kalia, P.; Mehmood, K. Predictive sustainability model based on the theory of planned behavior incorporating ecological conscience and moral obligation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Beliefs, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Decrop, A. Tourists’ decision-making and behavior processes. In Consumer Behavior in Travel and Tourism; Pizam, A., Mansfeld, Y., Eds.; The Haworrth Hospitality Press: Binghamton, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 103–133. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, T.M.; Wu, H.C. How do environmental knowledge, environmental sensitivity, and place attachment affect environmentally responsible behavior? An integrated approach for sustainable island tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 557–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gärling, T.; Golledge, R.G. Environmental perception and cognition. In Advance in Environment, Behavior, and Design; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1989; pp. 203–236. [Google Scholar]

- Ittelson, W. Environment Perception and Contemporary Perceptual Theory. In Environment and Cognition; Ittelson, W.H., Ed.; Seminar: New York, NY, USA, 1973; pp. 141–154. [Google Scholar]

- Mannell, R.C.; Iso-Ahola, S.E. Psychological nature of leisure and tourism experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 1987, 14, 314–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albayrak, T.; Caber, M. Destination attribute effects on rock climbing tourist satisfaction: An Asymmetric Impact-Performance Analysis. Tour. Geogr. 2016, 18, 280–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryglas, D.; Salamaga, M. Applying destination attribute segmentation to health tourists: A case study of Polish spa resorts. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 34, 503–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Wang, G.; Marcouiller, D.W. A scientometric review of pro-poor tourism research: Visualization and analysis. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 30, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-J.; Li, W.-C. A study on the hot spring leisure experience and happiness of Generation X and Generation Y in Taiwan. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 25, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, R.C.; Witt, S.F.; Hamer, C. Tourism as experience the case of Heritage parks. Ann. Tour. Res. 1998, 25, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennington-Gray, L.A.; Kersteter, D.L. What do university-educated women want from their pleasure travel experiences? J. Travel Res. 2001, 40, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Um, S.; Chon, K.; Ro, Y. Antecedents of revisit intention. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 1141–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirakaya, E.; Woodside, A.G. Building and testing theories of decision making by travellers. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 815–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewell, B.; McKinnon, S. Movie tourism—a new form of cultural landscape? J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2008, 24, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guangzhou Statistics Bureau. 2020. Available online: http://www.gz.gov.cn/zwgk/sjfb/tjgb/content/post_7177238.html (accessed on 16 July 2021).

- The People’s Government of Guangzhou Municipality. 2010. Available online: http://www.gz.gov.cn/guangzhouinternational/visitors/whattodo/sportsandrecreation/hotspring/content/post_2998905.htm (accessed on 16 July 2021).

- SpaChina. 2018. Available online: https://spachina.com/2018/11/01/history-of-the-conghua-hot-spring/ (accessed on 16 July 2021).

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.; Gerbing, D. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, J.M. What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joreskog, K.G.; Sorbom, D. LISREL 8: User’s Reference Guide; Scientific Software International: Chicago, IL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

| Scale Item | Mean | Factor Loadings | t-Value a | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environment cognition | 0.67 | |||

| Convenient transportation and infrastructure. | 4.11 | 0.69 | -- | |

| Comfortable and clean destination. | 3.98 | 0.62 | 7.52 *** | |

| Reasonable price and value for money in the category of food and souvenirs. | 3.79 | 0.59 | 7.32 *** | |

| Hot springs experience | 0.62 | |||

| Bathing in a hot spring can be physically and mentally refreshing. | 4.06 | 0.68 | -- | |

| It is interesting to experience the diversity of recreation facilities at the hot spring destination. | 3.86 | 0.50 | 5.40 *** | |

| It helps to understand the concept of hot spring integrated with Chinese medicine to maintain health. | 3.75 | 0.54 | 4.93 *** | |

| It creates awareness of various bathing themes (such as herbal baths). | 3.32 | 0.43 | 4.11 *** | |

| Food experience | 0.80 | |||

| I experienced a type of local food-related activity. | 3.87 | 0.88 | -- | |

| I enjoyed the local cuisine. | 3.85 | 0.75 | 5.11 *** | |

| Attitude toward Cultural Landscape | 0.72 | |||

| I identify strongly with the landscape of hot spring villas and hotels. | 3.78 | 0.60 | -- | |

| The landscape of hot spring steam means a lot to me. | 3.82 | 0.71 | 8.03 *** | |

| Early hot spring retreat buildings cannot be substituted for other hot spring area buildings. | 4.12 | 0.69 | 7.93 *** | |

| The landscape of hot spring fountain facilities was very special to me. | 3.61 | 0.50 | 6.38 *** | |

| Revisit intention | 0.69 | |||

| I intend to recommend. | 3.54 | 0.76 | -- | |

| I intend to revisit. | 3.74 | 0.69 | 5.85 *** |

| Environmental Cognition | Hot Spring Experience | Food Experience | Attitude toward Cultural Landscape | Revisit Intention | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental cognition | 0.632 | ||||

| Hot spring experience | 0.237 | 0.510 | |||

| Food experience | 0.172 | 0.209 | 0.819 | ||

| Attitude toward cultural landscape | 0.479 | 0.236 | 0.198 | 0.632 | |

| Revisit intention | 0.185 | 0.314 | 0.231 | 0.259 | 0.530 |

| Antecedent Variable | Affected Variables | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hot Spring Experience | Food Experience | Attitude toward Cultural Landscape | Tourists’ Revisit Intentions | |

| Environment cognition | ||||

| Direct effect | 0.91 | 0.27 | -- | -- |

| Indirect effect | -- | -- | 0.78 | 0.27 |

| Total effect | 0.91 | 0.27 | 0.78 | 0.27 |

| Hot springs experience | ||||

| Direct effect | -- | -- | 0.86 | -- |

| Indirect effect | -- | -- | -- | 0.30 |

| Total effect | -- | -- | 0.86 | 0.30 |

| Food experience | ||||

| Direct effect | -- | -- | n.s. | -- |

| Indirect effect | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Total effect | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Attitude toward Cultural Landscape | ||||

| Direct effect | -- | -- | -- | 0.35 |

| Indirect effect | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Total effect | -- | -- | -- | 0.35 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, W.-C.; Lin, C.-H. A Model for Sustainable Tourism Development of Hot Spring Destinations Following Poverty Alleviation: Understanding the Tourists’ Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9856. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179856

Wang W-C, Lin C-H. A Model for Sustainable Tourism Development of Hot Spring Destinations Following Poverty Alleviation: Understanding the Tourists’ Perspective. Sustainability. 2021; 13(17):9856. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179856

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Wei-Ching, and Chung-Hsien Lin. 2021. "A Model for Sustainable Tourism Development of Hot Spring Destinations Following Poverty Alleviation: Understanding the Tourists’ Perspective" Sustainability 13, no. 17: 9856. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179856

APA StyleWang, W.-C., & Lin, C.-H. (2021). A Model for Sustainable Tourism Development of Hot Spring Destinations Following Poverty Alleviation: Understanding the Tourists’ Perspective. Sustainability, 13(17), 9856. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179856