1. Introduction

Education, which has always been conducted in physical settings, is gradually shifting to online classes. Online education is becoming more prominent as non-face-to-face culture is emphasized due to the recent COVID-19 crisis. Schools are also gradually increasing the proportion of online education. However, online education alone has its limitations. Thus, blended learning, which bolsters online teaching with physical classes, has attracted new attention. The OSS in Korea, which has been actively operated with a long history, is receiving a lot of attention because students can take Internet courses using various learning media such as PCs, smartphones, and tablets, making the learning environment ubiquitous [

1]. The OSS in Korea has been in existence since 1974 as a public high school. Classes were broadcast twice a month on radio, which was the main means of electronic communication at the time. Currently, the OSS is building and operating a blended learning cyber education system (hereafter “CES”) comprising regular online classes and twice-monthly physical ones.

Through the OSS, more than 240,000 students have received secondary education. The CES, which was conducted for all grades in 2008, has recently emphasized the “realization of social justice” aimed at changing the paradigm to a more “consumer-centered, learner-centered” approach and placing more emphasis on the socially and educationally disadvantaged. The content and academic management systems are provided according to the level and situation of the participants. The class procedures and the accumulation of content, which are based on both online and physically attended classes, will be able to guide much of the innovation of the public education system required for the future. However, to ensure that this preparation is done properly, two key questions must be addressed. These are as follows: (1) “What are the structural, institutional, and actor context factors that facilitate and constrain changes in the OSSP?”; (2) “What is the interaction among the structural, institutional, and actor context factors that facilitate and constrain changes in the OSSP?” The current study examines policymaking since the establishment of the OSS to the present day from a historical institutional perspective. By analyzing the factors and events that specifically facilitated and constrained the policy changes, the study points to measures that will be needed to develop sustainable policies for the future educational environment.

2. The OSSP in Korea

The OSSP started in 1973 with the enactment of the “Plan for the Establishment and Operation of OSS” and the revision of the Education Act to allow OSS education courses in national and public schools. In the following year, open high schools were established in various parts of the country and later expanded. One motive for the establishment of Korea Open High School was to help solve certain socioeconomic challenges that arose in the 1970s in Korea. In that decade, there was an increase in the demand for labor in the burgeoning industrial sector, which was a cornerstone of State policy for economic development. At the same time, various social problems arose, such as inadequate school places for the baby boomers born in the 1960s, an increase in the number of middle-aged and senior citizens who had limited or no formal education, and the problem of repeat students who had failed the high school combined exam.

In response, the government established the OSS to utilize remote education. The institutional structure was a general national and public high school, rather than a more specialized type that would have required more financial investment and time. Among the functions of the OSS, “realization of social justice” was the most prominent aim. In other words, most of the students who enter the OSS are those who have failed in the standard schools or who are unable to attend general high schools for economic or personal reasons. Thus, the core policy of the OSS can be regarded as providing a “fair equality of opportunity” to everyone who wants to acquire a secondary education, as mandated by the “social justice” concept [

2]. This policy has a positive personal and social impact, such as the recovery of self-confidence and social self-esteem achieved by acquiring educational qualifications, the spread of lifelong education, improvement in the national education level, a reduction in the educational gap, and a contribution to national development.

The OSS Project is operated under the leadership of the OSS Project Steering Committee, which includes the Ministry of Education (MOE), the Korea Educational Development Institute (KEDI), the municipal and provincial education offices, and unit schools. The OSS Steering Committee is responsible for discussion and decision making on policy projects, as well as budget and account management. The MOE is in charge of establishing and implementing OSS policies from the legal and institutional bases. The Center for Digital Education Research in the KEDI develops and provides remote classes and related content through a regular middle/high school curriculum via the Internet, overseeing and continually analyzing the entire operation and assistance. The municipal and provincial education offices provide administrative and financial support for the establishment of the OSS under their jurisdiction, whereas the unit schools are in charge of their day-to-day operations.

3. Historical Institutionalism

By examining the historical context of the OSS policies, the current study prescribes the optimum direction for future OSS policies by analyzing factors that facilitated or constrained policy changes and the relevant pathways for such changes. To this end, the theory of historical institutionalism is applied, but with an avoidance of the “institutional determinism” that typically informs historical institutionalism. Instead, this paradigm is utilized for the “integrated approach of structure, institutions, and actor levels” and the “view of gradual change”. Before beginning the analysis, the criteria and framework for gradual change and an integrated approach involving structure, institution, and actor levels are outlined below.

3.1. View of Gradual Change

The “view of gradual change” was based on

Table 1 and the “type of institutional change” in Streck and Thelen [

3], which noted that the process of change was gradual and led to “gradual transformation”.

However, unlike Mahoney and Thelen’s [

9] distinction of evolutionary type as “transition, drift, lumpy, and replacement”, the present study was reconstructed as shown in

Table 2 with a gradual “incomplete break” and “complete break”.

In addition, the “view of gradual change” was a study by Hacker [

10] and Mahoney and Thelen [

9] that explored the type of path evolution [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16] and two pathways commonly derived, as shown in

Table 3. As Lee and Lee [

15] revealed, Hacker [

10] and Mahoney and Thelen [

9] mostly distinguished the types of path evolution on the basis of internal barriers (institutional features) and external ones (political contexts). The two studies generally agree on the criteria for determining the type of pathway, but the interpretation of these criteria is contradictory. However, since the characteristics themselves are similar, this study distinguished the types of evolution on the basis of the characteristics of each type presented in the preceding study.

Ha [

4], Streck and Thelen [

3], and Mahoney and Thelen [

9] all considered the types of path evolution to be “completely disconnected”. However, the typology of features shows that “drift, layering, and conversion”, for example, is often the result of incomplete disconnection, as this tends to remain within the existing system. Therefore, in the current study, this category is presented separately as incomplete and complete disconnection. The newly created system is also “path-dependent” because the existing system is firmly established, thus restricting choice [

17,

18,

19]. Incomplete disconnection is indicative of this point. Streck and Thelen [

3] defined displacement as a radical disconnection due to external shocks, such as natural disaster or war.

However, Hacker [

10] and Mahoney and Thelen [

9] viewed displacement as a type of path evolution (a gentle transformation as outlined in

Table 1) that was a “gradual disconnect” rather than a radical change. In other words, the path evolution displacement appears to be the outcome of cumulative gradual change, not external, and distinct from the “breakdown and replacement” in

Table 1. In addition, this study holds that one type of evolution cannot explain the process via which a new system is constructed. Instead, evolution was found to be a result of complete disconnection by accumulating incomplete disconnection through a gradual process defined as “path-dependent evolution” [

20].

3.2. Integrated Approach for Structure–Institution–Actor Level

An analysis was performed on the “integrated approach at structure, institution, and actor levels” based on Mahoney and Snyder [

21]. Mahoney and Snyder posited that structure is created at the institutional and actor levels. The structure level is divided into macroscopic and domestic structures and presented as a variable in the world system (power structure), the ethnic and national levels (meaning economic or cultural), and the domestic class structure. The system level presents institutionalized ideology, the legal system, and the political system as variables. The actor level comprises social groups and leadership, with the variables being advocacy groups and political leadership.

4. Analytical Framework

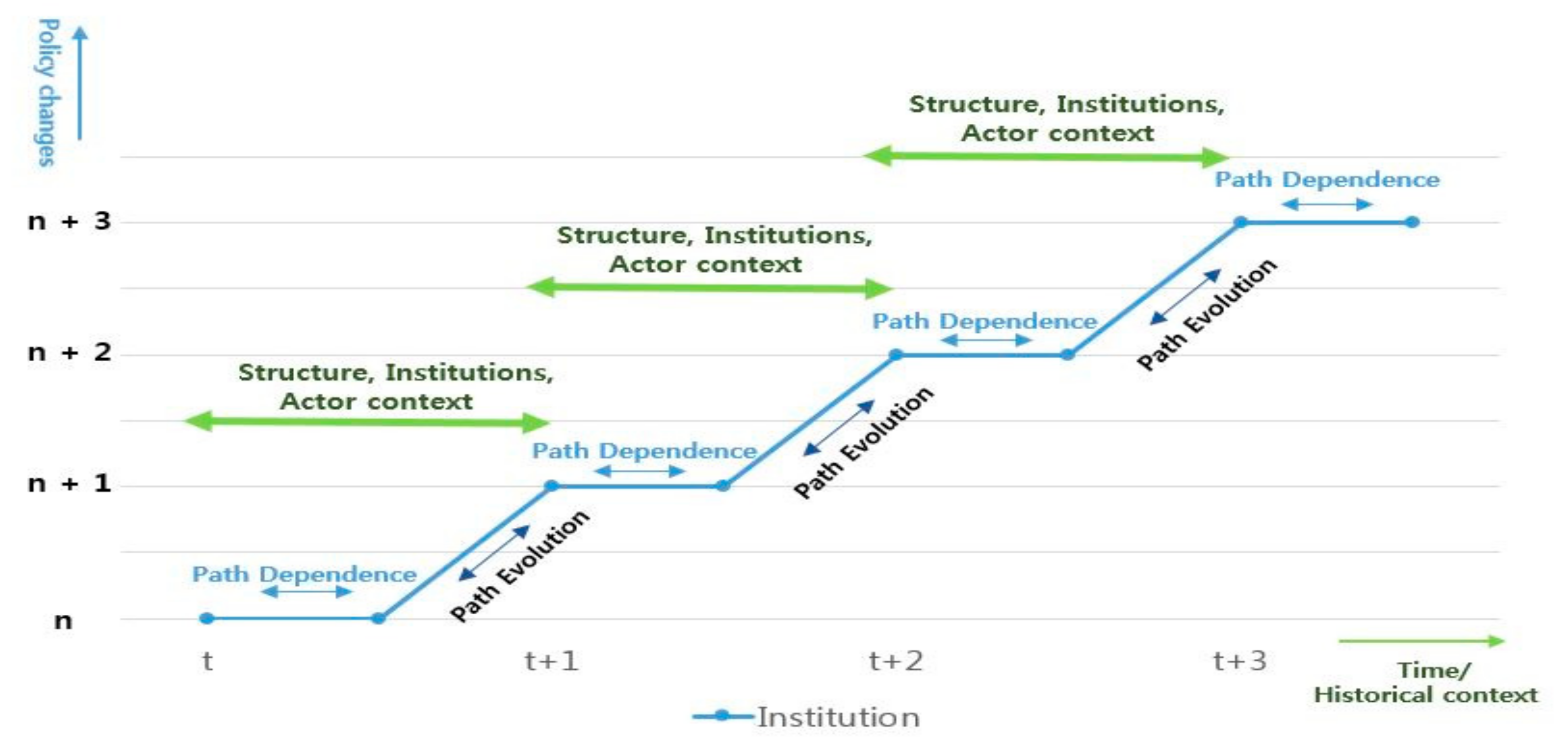

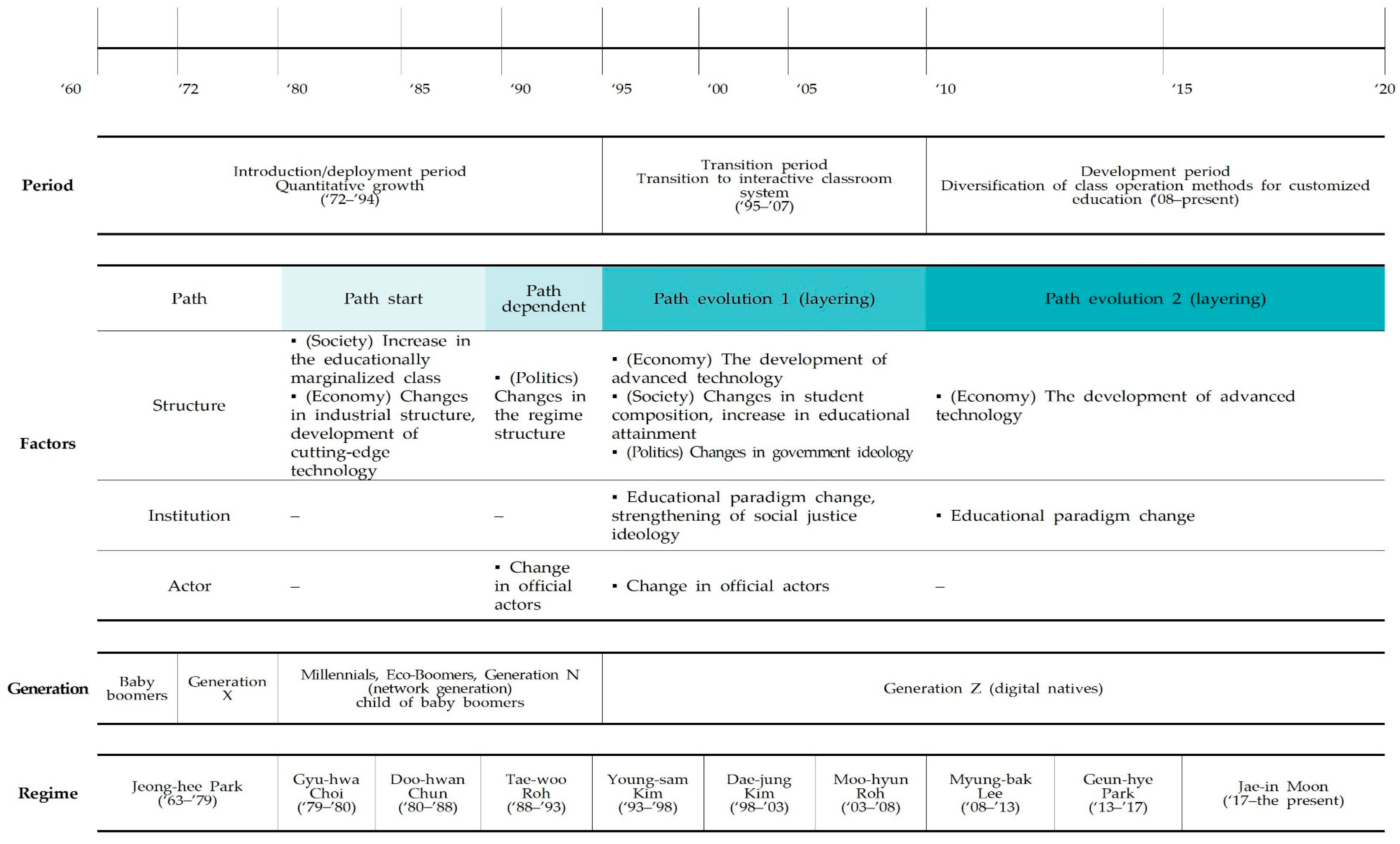

Since both “view of gradual change” and “integrated approach of structure, institution, and actor levels” were considered in the current study, the path evolution type of Mahoney and Thelen [

9], the path evolution process of Ha [

4], and the analytical framework of Shin and Jeon [

22] were altered to apply to the OSS [

20]. Examining the “view of gradual change” through the theory of historical institutionalism, the path of institutions (formal and informal) formed by chance according to “accidental events” or “critical periods” begins. Path evolution is also the type of path “drift”, “layering”, “conversion/redirection”, and “displacement” influenced by subfactors of the internal and external contexts of the system, i.e., structural, institutional, and actor context factors. It can be interpreted as a “path dependence” phenomenon in which subfactors are influenced but unintentionally maintain the characteristics of an already formed system [

23]. Specifically, the content of the analytical framework is constructed in the following manner: the system n is “started” by external requirements or by the influence of internal and external contexts at t. Afterward, the path becomes self-enhancing, macro and microscopic contextual factors (structure, drafting, and actor) accumulate, and the system is drift, layering, and conversion. In other words, at “t + 1” and “t + 2”, it evolves into a system of “n + 1” and “n + 2”. This path-dependent evolution accumulates and eventually evolves into a new system called “displacement” at the time of “t + 3”. The system is considered to have evolved because of the combined effect of all the contextual factors accumulated in the time flow from t to t + 1 as distinct from the effect of the contextual factors at a particular point in time (see

Figure 1).

Further discussion is needed on the criteria for determining at what point a particular plan was the result of a path-dependent evolution or a displacement by a new one. In the present study, researchers agree that “drift, layering, conversion, and displacement” based on the characteristics of the “path-evolution type” is a common outcome. Furthermore, detailed variables for each level are selected and analyzed in accordance with the study for “integrated access to structure, institution, and actor levels”. The “social, political, and economic change factors” were extracted as subfactors of the structural level, whereas the “social justice ideology” and “educational paradigm change” were extracted as subfactors of the institutional level, and the “official actors’ influence” was extracted and analyzed as subfactors of the actor’s level. In summary,

Table 4 shows the analysis criteria for this study.

5. Research Method

This study conducted a literature overview. This included the OSSP, budget status from the preparation stage of the establishment of the OSS in 1973–2020, the education policy and information service project of the MOE, IT industry development history, lifelong education policy, and education welfare policy. Specific data collection and research methods for target analysis were performed as described below.

First, the domestic and international literature was collected to examine the history of government’s education policy and the OSSP. The domestic literature included national documents (national policy data, press releases, policy implementation plans), research reports, and research papers. To this end, the MOE and the National Curriculum Information Center website collected policy data and press releases for each period and reviewed research reports from national institutions such as the KEDI and the Korea Institute of Academic Information.

Second, internal data from the Center for Digital Education Research (a department of the KEDI) were collected and referenced to analyze budget trends in the OSSP, distribution of student membership, information related to the establishment of various systems, and business execution. Based on the data collected, the development process of the OSSP was analyzed. The context factors of the structure, institution, and actor levels that emerged during the development process were extracted, and their influence of these factors on the process of change of the OSSP was gauged. The variation path was then tracked by compiling these factors.

6. Findings

6.1. Structural Context Factor

6.1.1. Social Fluctuation

The “educationally disadvantaged group” refers to people who have minimal educational opportunities because of their socioeconomic situation or who do not for a variety of reasons have a good fit with the standard educational system [

24] (p. 3). South Korea achieved rapid economic development through industrialization after the Korean War. Baby boomers (born between 1955 and 1963) went to middle school in 1969 with a standardized middle school pass; however, by the time they entered high school, the number of high school students had increased, with regular schools unable to accommodate all middle school students. In other words, many individuals from the baby boom generation were unable to get into regular high schools, thus failing to obtain “education opportunities” and creating educationally disadvantaged groups. This led the government to establish a new type of school called the OSS to ensure educational opportunities for all citizens. Thus, the social fluctuation factor of “increase in the number of the educationally disadvantaged groups” had a very significant impact on the trajectory of the OSSP.

Since the establishment of the OSS, interest in “the educationally disadvantaged groups” rose again with the IMF financial crisis of 1996 [

24]. At that time, school-age students temporarily increased among members of the open high school [

25]. In particular, the new government, which emerged after the foreign exchange crisis, made social polarization a national focus. This was the reason why the government invested 9.5 billion KRW (795,000 USD according to the exchange rate at the time) in changing the operating system of the open high school.

The changes in student composition affected management of the curriculum of the OSSP. Composed of school-age students in 1974, the OSS ran the same curriculum as ordinary high schools until the sixth curriculum. However, it should be noted that, while the sixth curriculum was applied collectively to all schools across the country, from the seventh curriculum (1997–2009), changes were implemented at their discretion by region and by school. Thus, unlike previous years, the curriculum was more flexible. Under the Regulations for Enforcement of the OSS Establishment [

26], the total number of classes for the OSS was adjusted to 168 units, equivalent to 80% of the current curriculum for general high schools. This change was impelled by a reduction in number of days of the OSS and class attendance, which was done to make classes more convenient for students [

25]. This change was instituted from 1995 when most OSS students were older than their school-age peers. It can be seen that the change in the composition of students affected the OSSP.

6.1.2. Economic Fluctuation

The “change in industrial structure” affected the inception of the policy path. It was during the industrialization shift that the OSS was established. In the 1970s, the government policy focus on heavy and chemical industries increased the demand for both unskilled and skilled workers for industrial sites [

27]. Urbanization and industrialization driven by economic development resulted in the rural population moving to cities where job prospects were better [

28]. As a result, the population became concentrated in Seoul and Busan, but disadvantaged education groups grew in these cities since baby boomers were at school age. In response, Seoul and Busan created a plan in 1972 to set up the open high school, with the government supporting the idea. This led to the establishment of the open high school in 1974; hence, it is possible to evaluate the “change in the industrial structure”, as well as the “increasing number of school-age students” and the “change in the industrial structure”, of the OSSP.

The introduction of advanced technology in the Korean economy has been a key factor in policy changes since the start of the OSSP to the present day. Specifically, the popularity of radio broadcasts allowed the creation of the OSSP, and the computers and IT technology development provided the means to fundamentally change and develop interactive classes. In addition, the development and distribution of smartphones that became widespread around 2010 facilitated the shift of the OSSP to a customized operating system. However, technology has not been the only factor driving change in the OSSP, given that efforts to switch to an OSS operating system through TV media in 1987 were soon frustrated by various contextual factors; thus, training continued through radio broadcasting for the next decade.

6.1.3. Political Fluctuations

The “local autonomy system”, which was implemented in the early 1990s, both facilitated and constrained the OSSP. The local education self-governing system was started in 1952 when the Education Act was enacted and promulgated. This was partially implemented in June of the same year, but abolished in the wake of the May 16 military regime in 1961, after which the local education autonomy system was adopted at the municipal and provincial levels from 1964 to the 1980s. Despite operating nominally for more than 40 years, this system was only officially established in March 1991 when the Act on Local Autonomy was passed. This was also the first time that a practical system conforming to the original ideology of autonomous education authorities was implemented. An education committee to lead education autonomy was elected in August, and an education committee was formed in each city and province. Each committee was a deliberative and voting body separate from the general local council of the 1990s, and the education superintendent was required to review and approve the ordinance, budget, and settlement proposals in advance and implement the office.

In addition to the local education grants allocated by the central government, expenses were to be covered by special fees for education and use, as well as other property income related to education, local finance grants, and transfer payments from the local governments’ general accounts, along with education scholarships. Securing local education funds can be a requirement for local education autonomy to be realized properly; however, with the responsibility limits of central and local governments being unclear, local governments’ transfer of education funds remains minuscule to this day [

25]. However, this change led to more interest and participation in the city’s efforts by making the OSS Project implemented by city and province rather than national policy. For example, in Daegu, the nation’s first branch-type OSS was opened in 2016 [

29], and the youth class of the open middle school was expanded, enabling the establishment of a public alternative school [

30] for the first time.

Changes in government structure and political ideology had a significant influence on changes in the OSSP. First, the OSSP was path-dependent regardless of changes in the structure of the regime. After examining the influence of “change in regime structure”, divided into “military regime” and “civilian regime”, it was found that, although the OSSP began under the military regime, it remained unalterable despite the demand for change in the operating system (the development of TV media). Since 1993, when the military regime came to an end and the civilian government took power, the OSSP has only attempted to transform the operating system and has continued to develop.

Second, “changing political ideas” can be measured as a national agenda focusing on each administration. The Roh Moo-hyun regime adheres to a “resolve social polarization” as a core of previous administrations [

31,

32]. This was a national agenda consistent with the purpose of the OSS. In particular, active investment is usually made to attain national goals, but the fact that operation costs of the center for the OSS were doubled in 2004 from the 2002 budget implies that this investment is part of the national agenda. The main reason for the rise in operating costs is the development of a CES. The government decided to invest 9.5 billion KRW for the OSS Cyber Education System construction project from 2004 to 2008 [

33,

34].

This was performed immediately after the inauguration of President Roh Moo-hyun (25 February 2003), and the media held that this support would greatly contribute to “resolving the knowledge and information gap for the underprivileged” [

33] (pp. 22–25). It is noteworthy that the policy direction of “advancement of the educational environment through the conversion of interactive multimedia learning methods” was presented as part of the revitalization of the open high schools in the Comprehensive Plan for Lifelong Learning Promotion announced by the Kim Dae-jung administration in 2002.

6.2. Institutional Context Factor

6.2.1. Social Justice Ideology

Social justice ideology served as a policy facilitator that attracted significant investment into the OSS during the transition period. In general, “social justice” means “distributive justice”. This is the inevitable result of bringing “social structural problems” or problems arising from the gap between the rich and the poor to the core of “justice theory”. The definition of distribution boils down to the question of whether distribution will be performed according to market principles, equity criteria, or by random factors such as birth into a particular class, socioeconomic benefits, innate abilities or talents, or whether distribution will focus on the deficient through differential principles.

Rawls [

2] insisted that the distribution of goods was unequal from a moral point of view, with the share of resources determined by arbitrary factors such as birth, social or economic advantage, innate ability or talent, or the free market that either distributes birthright using a caste system or recognizes opportunity equality and equality, whereby only the “principle of differentials” is equal to income and wealth distribution. That is, one’s own interests from a given natural or social environment should serve the common good. This is seen as the most persuasive argument for advocating a more equal society under the ideology of liberal equality that holds that human dignity should be respected equally by everyone. In general, “social justice” tends to be based on two Rawlsian principles (principle of greatest liberty, principle of difference) and determines social justice on the basis of the value of “equality as fair opportunity equality” [

2] (p. 266). It is also emphasized that the role of the state, i.e., the realization of social justice through national policy, is the best possible agent of distribution [

23].

Therefore, using social justice as the guiding principle for carrying out state affairs—providing and distributing fair opportunities that make the start equal—means that the state will actively step in and play a role. The Roh Moo-hyun government made “resolve social polarization” one of the catchphrases of its national policy, and the social polarization phenomenon, which was exacerbated by the IMF financial crisis, had to be highlighted as an important task for the government at that time [

35].

President Roh Moo-hyun in his inaugural address said, “The days when fouls and privileges are acceptable should be over. The climate of justice being defeated and opportunists gaining power must be stopped. Let’s set the principles straight and build a trust society. Let’s move on to a successful society where people strive justly. Most people should feel proud of what they do to promote honesty and integrity.” [

36]. The government’s task of resolving social polarization was based on the ideology of social justice, and it was able to provide unprecedented support in the management history of the OSS by allocating 9.5 billion KRW over 5 years to improve the operation system of the OSS.

6.2.2. Educational Paradigm Change

The civilian government’s 5.31 Educational Reform of 1995 ushered in a change in the education paradigm that was described as “consumer-oriented, learner-oriented”. This was part of an effort to break away from the ideological education instituted during the military regime. This paradigm change persists to this day and has greatly influenced the OSSP. Specifically, the Open High School Computer Communication Learning System was developed in 1997, the “CES” was studied in 2004, and the system was built in 2008 while actively applying and researching educational methods using IT technology to create a “consumer-oriented” and “learner-oriented” pedagogy. In 2020, the CES was upgraded, and specialized subjects were developed, including “customer-tailored” projects such as “e-school for students”, “school for you”, “online joint curriculum”, and “learning support project for preschoolers/discontinued students” operating system diversification. Thus, the 5.31 education reform had a significant impact on the open schools policy.

6.3. Actor Context Factor

6.3.1. Fluctuations in the Official Actors at the Decision Level

The political variable “implementation of local autonomy system” impacted changes in the system of administrative and financial support for the operation of the OSS. This can be seen as a change in the official actors who made policy decisions. Specifically, the authority previously held by the MOE to determine the budget and allocate budgets to each city/province was transferred to each metropolitan/provincial office of education. In addition, all the subsidies (50% of the textbook bill), which were subsidized as part of the nation’s lifelong education support policy, were given to students on the basis of the principle of paying the beneficiary.

In line with this trend, the current operating expenses of the Center for OSS of the KEDI, which were previously decided by the MOE, were set up in consultation with the respective municipal and provincial education offices [

27]. Accordingly, all administrative and financial matters regarding the operation of open high schools were changed to a structure determined by the Committee for Operation of OSS, which includes the MOE, the KEDI, and the city and the province. Thus, changes in the official actors on the determinative level had to be adapted to changes in the administrative and financial consultative structure, serving to limit policy changes such as constraining investments.

6.3.2. Fluctuations in the Official Actors at the Executive Level

There have been two changes in the “official actor’s variation in the enforcement level” over the past 45 years. As the Educational Broadcasting System (EBS) affiliated with the KEDI became more or less independent in 1991, the rights to produce and transmit programs were transferred to the EBS from the Center for OSS of the KEDI. This created many difficulties in the interaction between the KEDI and the educational broadcasting service, since the broadcasting transmission and content operation were done separately. This change limited the policy shift to the TV media OSS class, which was the key reason the OSS educational media was forced to go straight from radio to computer with no television phase. It is also worth paying attention to the separation and independence of the affiliated EBS education broadcasting and multimedia education research center, also known as the Korea Education Broadcasting Institute. Since the Multimedia Education Research Center was in charge of the computer communication learning system of the OSS, this had a significant influence on the operation of the OSS.

The rationale was that, 7 years after the establishment of the Korea Education Broadcasting Institute, the OSS independently created and transitioned to a CES (a Web-Based Interactive Education System). Specifically, the shift to a “two-way multimedia teaching and learning method” based online was promoted in 2002 under the “Comprehensive Plan for Lifelong Learning Promotion”, as high-speed Internet networks were distributed to households in the late 1990 and the number of Korean Internet users increased from 138,000 in 1994 to 19 million in 2000. In 2004, the Korea Education and Research Information Service (KERIS) began pilot research by launching the Cyber Home Learning System for students. At the same time, the KEDI launched a study on the operation of the OSS CES to promote the transition to a new operating system independently of KERIS and to expand the CES to the previous school year in 2008. In summary, the separation and independence of EBS acted as a constraining factor in policy changes, whereas the separation and independence of the Multimedia Education Research Center facilitated policy changes.

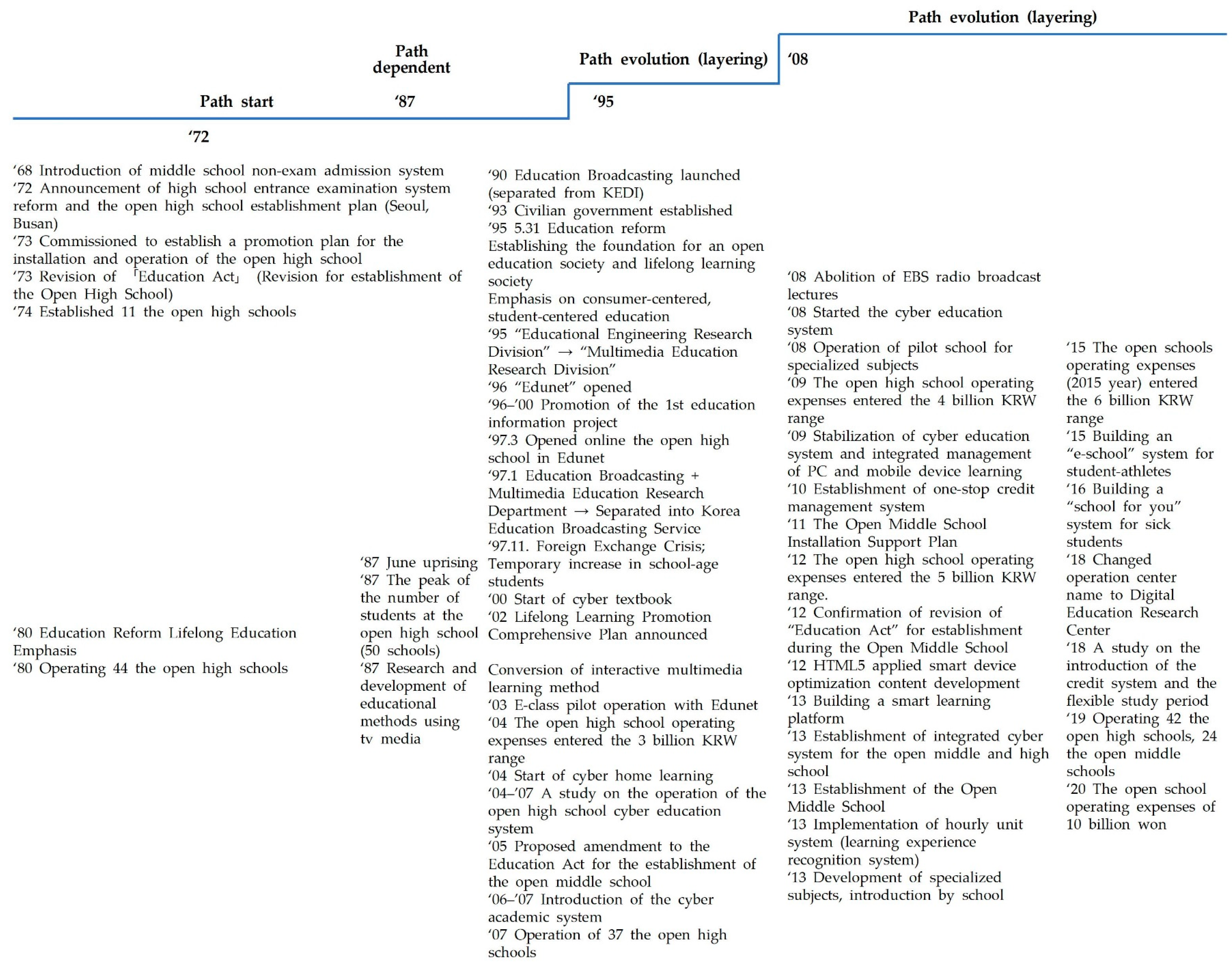

6.4. Policy Shift Path Factor

6.4.1. Path Start

“Path start” means that the system is inadvertently initiated and created during critical periods when several alternatives to the development of the plan are available [

20,

37,

38]. In this regard, the OSSP was initiated by the establishment of the OSS in 1974 to solve social problems that had become more prevalent among educationally disadvantaged groups. However, the change in industrial structure at the beginning of this path led to an increased need for manpower, with remote education enabled by the popularity of radio also contributing to the shift in policy.

6.4.2. Path Dependence

Elements affecting the dependence of the path were “change in the structure of the regime”, “implementation of the local autonomy system”, and “change in official actors”. The first factor can be generally divided into military and civilian regimes. The OSSP continued without much change for approximately 20 years from the beginning during the military regime until the arrival of the civilian government that, despite the rapid economic growth, did not actively invest in high school classes using TV media. In addition, “the implementation of the local autonomy system” restricted a change in policy by bringing about a drastic change in the financial and operating systems of the OSS. “The change in official actors” led to confusion in the operation of the OSS since the main body of the government, the government, and the state-run education office were changed to the municipal and provincial education offices. Similarly, the EBS, which was in charge of broadcasting and transmission from the executive level, was separated from the KEDI, resulting in the failure of the switch to TV.

6.4.3. Path Evolution

Elements that have affected path evolution are “change in student composition”, “advance of the most advanced technology”, “change in regime ideology”, “increase in the number of educationally disadvantaged groups”, “change in education paradigm”, “change in official actors (executive levels)”, “implementation of local autonomy”, and “social justice ideology”. All of these elements served to facilitate policy changes to a CES (a Web-Based Interactive Education System). In addition, the Roh Moo-hyun administration, which used the resolution of social polarization as its national agenda, centered on the realization of “social justice”. Following this, the policy once again influenced the path evolution, and, on this basis, the OSS could welcome the progress period. These historically unprecedented changes created the key elements in the evolution of the education system, such as “changes in student composition”, “change in industrial structure”, “advancement of state-of-the-art technology”, and “change in education paradigm”. These affected the policy once again by enabling “customer-tailored education” to bring about diversification of the operating system. The “policy shift to two-way teaching and learning system” and the “policy shift to consumer-centered education” in the transition period correspond to “changes in the way the existing system operates”, where components of the existing system remain the same and some new components are added to it, which is “layering”. In the end, the OSSP was transformed under the influence of various historical developments, so that the policy was changed to the stage of “path start–path dependence–path evolution (layering)–path evolution (layering).” The results of the comprehensive analysis of the path movement of the OSSP are shown in

Figure 2.

7. Discussion and Conclusions

The present study examined policies from the establishment of the OSS to the present through Historical Institutionalism and proposed measures to develop policies more suitable for future educational environments through analyzing the factors and policy pathways that specifically facilitated and constrained policy changes. Two research issues were identified: “What are the structural, institutional, and actor context factors that facilitate and constrain changes in the OSSP?” “What is the interaction among the structural, institutional, and actor context factors that facilitate and constrain changes in the OSSP?” The conclusions of this research question are described below.

First, the contextual factors facilitated or constrained changes in the OSSP. Specifically, the structural context factors (e.g., “change in the industrial structure” and “advancement of the most advanced technologies”) and the institutional context factors (e.g., “socialist ideology”) facilitated changes in policy. Meanwhile, the structural context factors (e.g., “implementation of the local autonomy system” and “changes in the structure of government”) constrained changes in policy. An actor context factor (e.g., “formal actor variation”) served as a factor that restricted or facilitated policy changes.

In other words, the Open Secondary School (OSS) has developed by actively responding to political, economic, social, and technological changes. The OSS was established as the industrial structure changed and cutting-edge technology developed, requiring a large number of talents. Additionally, at the time of establishment, the OSS intended to foster national talents, but it is currently operating for educational welfare. As a result, the OSS students changed from young people to middle-aged or educationally disadvantaged groups. It is worth noting that the OSS system provides educational opportunities to the underprivileged, enhances social justice, and strengthens financial support to those in need. These changes resulted in the OSS actively adapting to the influence of local self-government and changes in government further improving the level of educational welfare. This means that the OSS has changed its identity in the past and present, but it is continuously developing in response to changes in demand.

Second, the structure, institution, and actor context factors interacted with each other to facilitate or constrain policy changes. The implementation of the local autonomy system, which is a factor of “path dependence” and the related level of the structure, affected the “official actor variation” that was a factor of the actor’s level and restricted policy changes. In addition, “advance of the most advanced technology” and “change in the structure” factors affected each other and restricted policy changes. In other words, the military regime, i.e., the “change in the structure of the regime”, functioned as a limiting factor in which the conversion of the medium was not realized by lack of investing in the OSS operation despite the effect of the “advancement of the most advanced technologies”.

With regard to the evolution of the path, the structural context factors “change in student composition”, “the occurrence of the class outside of education”, “advanced technology development”, and “change in government ideology” were facilitated context factors in the “change in education paradigm”. In other words, the structural context has influenced the institutional context, leading to policy changes. In particular, the structural context factor “change in government ideology” factor was decisive in expanding investment in the transition to the CES in connection with the “social justice ideology”, which is an institutional contextual factor. Eventually, the structure, system, and actor context factors interacted with each other and constrained and facilitated changes in the OSSP.

Specifically, the OSS has faced crises due to several contextual limitations, but it has overcome them. For example, it was difficult to provide financial support for students at the time when national financial support was delegated to cities and provinces. However, the OSS naturally overcame this crisis according to the change in government. In other words, the OSS was able to provide more educational opportunities to the educationally disadvantaged class by capitalizing on the people’s desire for social justice after the end of the military regime. Financial support was also accompanied by a shift from radio media to cyber education systems, and the OSS was transformed into the most actively responding school in the era of the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

Several policy efforts will be needed for Korea’s OSS to function in the future. First, it is necessary to build sustainable a human and physical infrastructure that can respond sensitively to cutting-edge technology changes. “Changes in the most advanced technologies” was seen to be a key factor that facilitated policy changes from the beginning of the OSSP to the present. This will continue to have an impact in the future, and a virtuous cycle should be established to generate student demand on the basis of the human and physical infrastructure that can respond sensitively to such technological changes. In particular, the OSS should establish a big data analysis platform to inform policy decisions. The world is now in a time of digital change that transforms the working environment of companies and users’ daily lives on a digital basis. The education sector is no exception.

The content of all educational activities is being digitized. Smart textbooks, online class operations for middle and high school students, and the introduction of tutor-robots to elementary schools in 2019 are digitizing everyday education, and the OSS is also in the midst of such changes. The data should be considered an important resource to be collected and analyzed. This is because data come from digital media, and digital media has substance through data. The reason why the OSS is closer to the educational environment of the future than ordinary middle and high schools may be due to CES availability online. Therefore, instead of letting the data accumulate, the CES should be able to provide analysis systems for teachers to make full use of big data collected through online learning for analysis, including the learning trends of the entire student body to inform policy directions.

Second, it is necessary to develop customized educational content and to improve sustainable the educational environment for the educationally disadvantaged group. “Changes in student composition” served to facilitate policy changes. Multiculturalism will become more widespread in the future, whereas low birth rates and an aging population will engender a “change in the composition of students”. Therefore, it is necessary to respond to the “change in the composition of students” through efforts to develop customized educational content for the special and minor classes and improve continuous the educational environment.

We are still in the era of COVID-19. No one can guarantee when they will be safe from the threat of COVID-19. Therefore, instead of waiting for the end of this era, we must learn to survive in it. In this environment, Korea’s OSS can be presented as a model that guarantees educational opportunities. This is because the OSS use of EduTech methods allows for substantive instruction and learning even in catastrophic situations. We believe that the Korea’s OSS case provides important implications to contribute to the realization of educational welfare and social justice by minimizing the educational gap between schools and students and improving the quality of classroom (or virtual classroom) engagement.

An early version of this paper was presented at the Eighth Teaching and Education Conference, Vienna.