The Role of Value Appropriation Capability of Chinese Multinationals in Operating Cross-Border Business Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Theoretical Foundation and Hypothesis Development

2.1.1. The Importance of Value Appropriation among MNCs Facing Uncertainties

2.1.2. TIC and MC Contributions to MNC Performance

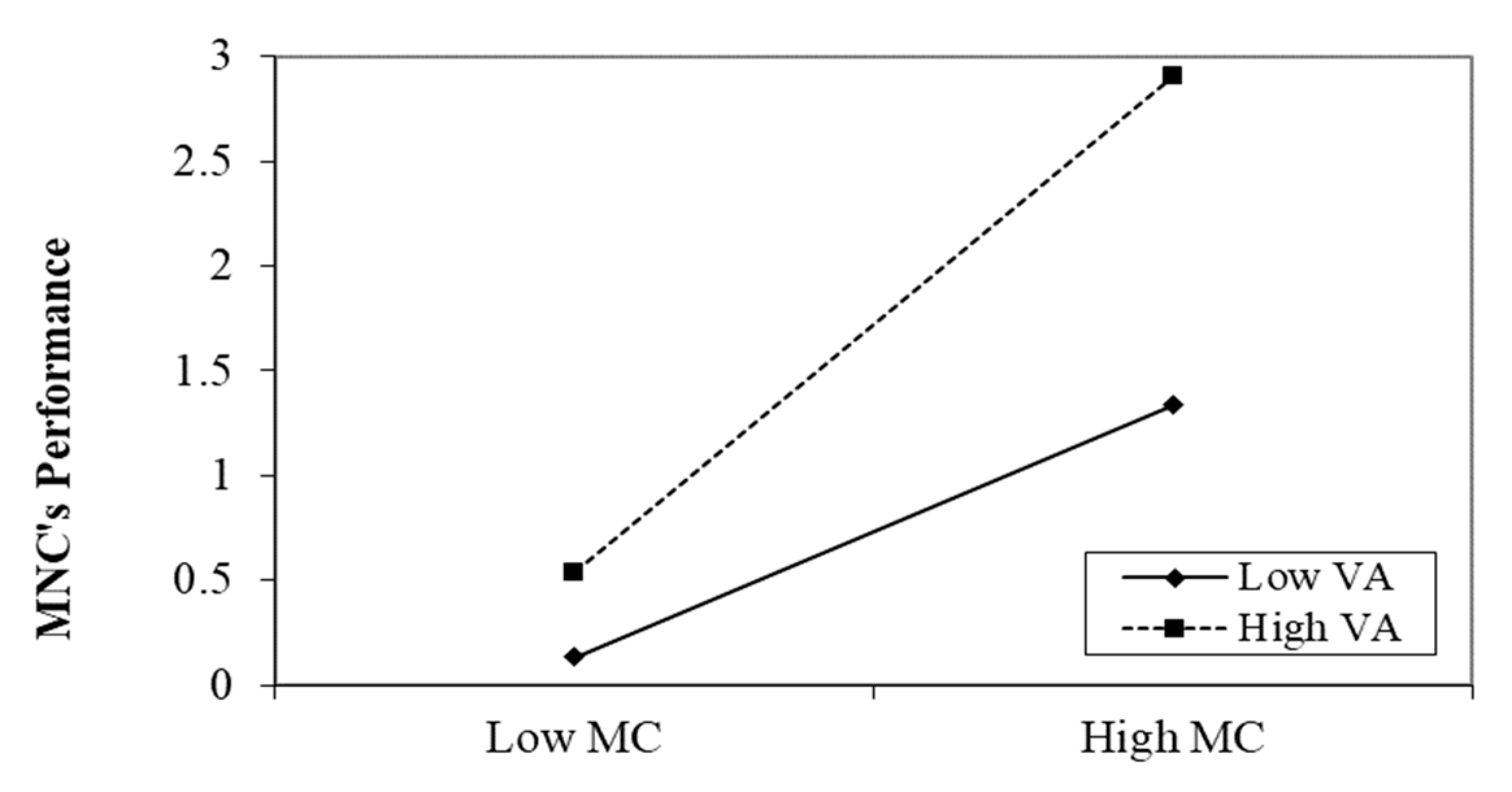

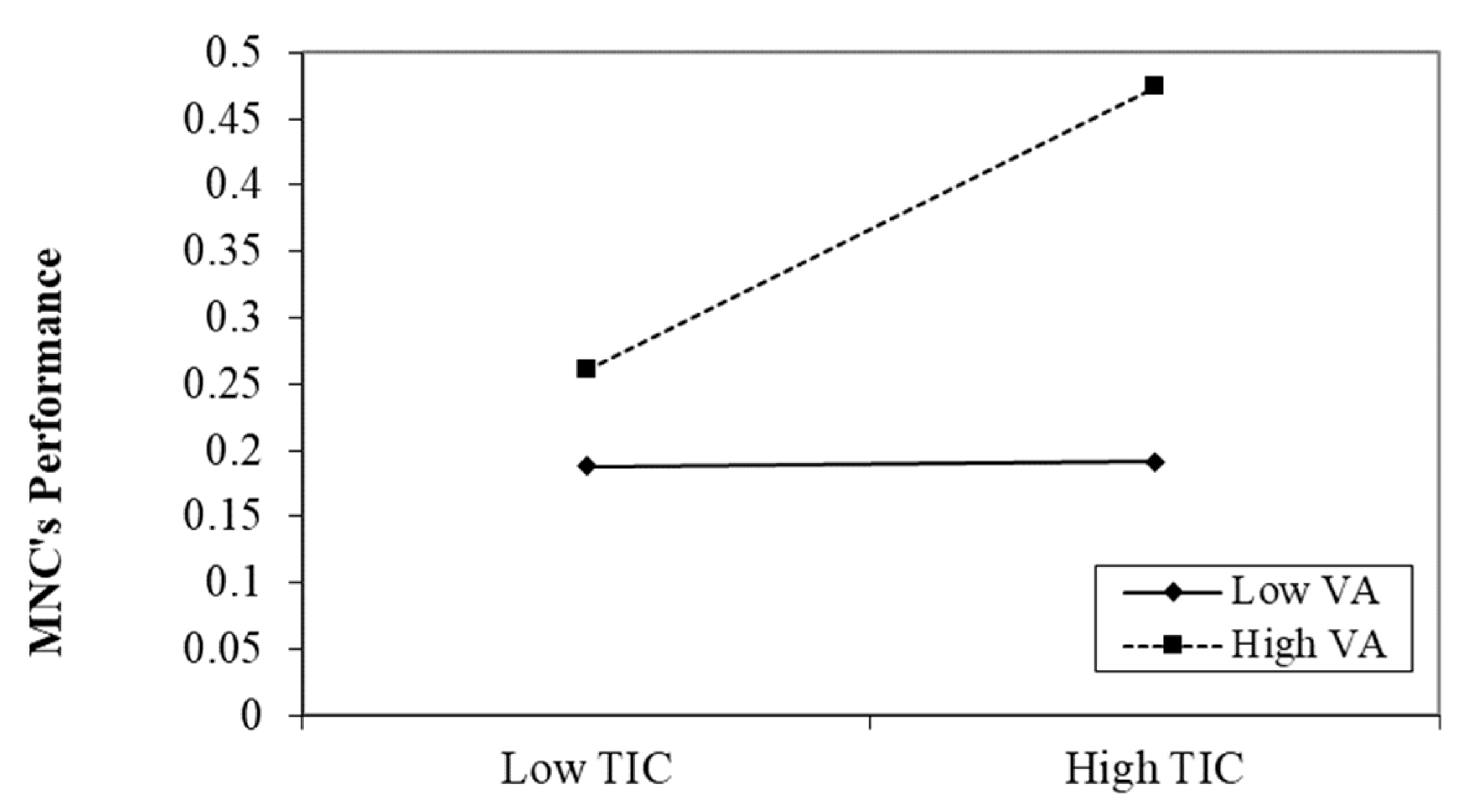

2.1.3. The Interaction Effect of TIC and MC on Firm Performance

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Sample and Data

2.2.2. Measurement

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

3.2. Analysis of Regression Results

3.3. Robustness Test

4. Conclusions and Discussion

5. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Demil, B.; Lecocq, X.; Ricart, J.E. Introduction to the SEJ special issue on business models: Business models within the domain of strategic entrepreneurship. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2015, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bei, X. Trademarks, specialized complementary assets, and the external sourcing of innovation. Res. Policy 2019, 48, 103709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zott, C.; Amit, R.; Massa, L. The business model: Recent developments and future research. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1019–1042. [Google Scholar]

- Gereffi, G.; Lee, J. Why the world suddenly cares about global supply chains. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2012, 48, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gereffi, G.; Lee, J. Economic and social upgrading in global value chains and industrial clusters: Why governance matters. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 133, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osiyevskyy, O.; Dewald, J. Explorative versus exploitative business model change: The cognitive antecedents of firm-level responses to disruptive innovation. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2015, 9, 58–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerulli, G. The impact of technological capabilities on invention: An investigation based on country responsiveness scores. World Dev. 2014, 59, 147–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H.; Rosenbloom, R.S. The role of the business model in capturing value from innovation: Evidence from Xerox corporation’s technology spin- off companies. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2002, 11, 529–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Huang, L.; Cheng, H.; Yang, L.; Ren, T. The moderating effect of cultural distance on the cross-border knowledge management and innovation quality of multinational corporations. J. Knowl. Manag. 2021, 25, 85–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, T.; Hu, Q.; Rowley, C.; Wang, S. Business models in the Asia-Pacific: Dynamic balancing of multiple cultures, innovation and value creation. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2021, 27, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, T.; Shi, Y.; Rowley, C.; Meng, J. Csonfucian business model canvas in the Asia Pacific: A Yin-Yang harmony cognition to value creation and innovation. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2021, 27, 342–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzola-Román, P.; Bayona-Sáez, C.; García-Marco, T. Profiting from collaborative innovation practices: Identifying organizational success factors along the process. J. Manag. Organ. 2019, 25, 239–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Zhu, T.; Lin, C.-L.; Chen, T.; Chin, T. Corporate social responsibility and firm performance in China’s manufacturing: A global perspective of business models. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, E.; Zou, S.M. Antecedents and consequences of marketing dynamic capabilities in international joint ventures. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2009, 40, 742–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.; Mittal, V.; Zhang, Y. Relative Strategic Emphasis and Firm Idiosyncratic Risk: The Moderating Role of Relative Performance and Demand Instability. J. Mark. 2017, 81, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelkafi, N.; Täuscher, K. Business models for sustainability from a system dynamics perspective. Organ. Environ. 2016, 29, 74–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, P.N. Innovation capability building and learning mechanisms in latecomer firms: Recent empirical contributions and implications for research. Can. J. Dev. Stud. 2012, 33, 14–40. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D.J. Business models, business strategy and innovation. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 172–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albino, P.; Dussauge, P.; Shaver, J. Firm non-market capabilities and the effect of supranational institutional safeguards on the location choice of international investments. Strateg. Manag. J. 2018, 39, 2770–2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccagnoli, M. Appropriability, preemption and firm performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2009, 30, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tower, A.P.; Hewett, K.; Saboo, A. Reexamining the tradeoff between value creation and value appropriation: The role of internal organizational resources vs. External strategic international alliances. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 123, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, R.M.; Clark, K.B. Architectural innovation: The reconfiguration of existing product technologies and the failure of established firms. Adm. Sci. Q. 1990, 35, 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, P. Catching up through developing innovation capability: Evidence from China’s telecom-equipment industry. Technovation 2006, 26, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H.W. Business model innovation: Opportunities and barriers. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcgahan, A.M.; Silverman, B.S. Profiting from technological innovation by others: The effect of competitor patenting on firm value. Res. Policy 2006, 35, 1222–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henkel, J.; Baldwin, C.Y.; Shih, W. IP modularity: Profiting from innovation by aligning product architecture with intellectual property. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2013, 55, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Malerba, F. Catch-up cycles and changes in industrial leadership: Windows of opportunity and responses of firms and countries in the evolution of sectoral systems. Res. Policy 2017, 46, 338–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaraswamy, A.; Mudambi, R.; Saranga, H.; Tripathy, A. Catch-up strategies in the Indian auto components industry: Domestic firms’ responses to market liberalization. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2012, 43, 368–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, E.; Martinelli, A.; Rabellotti, R. Is co-invention expediting technological catch up? A study of collaboration between emerging country firms and EU inventors. World Dev. 2016, 77, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, L. Stages of development of industrial technology in a developing country: A model. Res. Policy 1980, 9, 254–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camisón, C.; Villar-López, A. Organizational innovation as an enabler of technological innovation capabilities and firm performance. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 2891–2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, U.E.; Lema, R. The co-evolution of learning mechanisms and technological capabilities: Lessons from energy technologies in emerging economies. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 140, 241–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippetti, A.; Peyrache, A. The patterns of technological capabilities of countries: A dual approach using composite indicators and data envelopment analysis. World Dev. 2011, 39, 1108–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petralia, S.; Balland, P.A.; Morrison, A. Climbing the ladder of technological development. Res. Policy 2017, 46, 956–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Profiting from technological innovation: Implications for integration, collaboration, licensing and public policy. Res. Policy 1986, 15, 285–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuramoto, G.R.; Kindl, D.C.S. Internationalization process and technological capability trajectory of Iguaçu. J. Technol. Manag. Innov. 2012, 7, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fu, X.; Pietrobelli, C.; Soete, L. The role of foreign technology and indigenous innovation in the emerging economies: Technological change and catching-up. World Dev. 2011, 39, 1204–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenzi, P.; Troilo, G. Developing marketing capabilities for customer value creation through marketing-sales integration. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2006, 35, 974–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, G.S. The capabilities of market-driven organizations. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, N.A.; Vorhies, D.W.; Mason, C.H. Marketing orientation, marketing capabilities, and firm performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2009, 20, 909–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodlaj, M.; Coenders, G.; Zabkar, V. Responsive and proactive market orientation and innovation success under market and technological turbulence. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2012, 13, 666–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Li, H.; Wang, Z.; Duan, Y. Technology imports and self-innovation in the context of innovation quality. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2019, 214, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Bao, Y.; Olson, B.J. CEOs’ ambivalent interpretations, organizational market capabilities, and corporate entrepreneurship as responses to strategic issues. J. World Bus. 2017, 52, 312–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Variable Name | Variable Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | MNC performance (MP) | Growth rate of profit |

| Independent variables | Technological innovation capability (TIC) | The number of granted invention patents |

| Marketing capability (MC) | The natural logarithm of sales revenue | |

| Moderating variable | Value appropriation capability (VAC) | Added value/total output |

| Control variables | Corporation size (CS) | Logarithm of total assets |

| Corporation age (CA) | Difference between measure year and established year | |

| Subsidiary investment model (IM) | 1 means cross-border mergers and acquisitions, and 0 means others. | |

| Intensity of R&D expenditure investment (RDE) | R&D expenditure/main business income | |

| Intensity of R&D human capital investment (RDH) | Logarithm of R&D personnel | |

| Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) | The first five major stockholders to own stocks in the proportion of the sum of squares. |

| Variable | Mean | P50 | S.D | Min. | Max. | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MP | 19.09 | 0.038 | 1.610 | 10.34 | 24.51 | 4670 |

| TIC | 10.27 | 5.000 | 14.22 | 0.000 | 83.00 | 3116 |

| MC | 21.89 | 21.69 | 1.525 | 11.60 | 27.47 | 4669 |

| VAC | 0.230 | 0.112 | 1.482 | −1.000 | 58.84 | 4145 |

| CS | 22.45 | 22.25 | 1.364 | 17.02 | 27.75 | 4670 |

| CA | 16.38 | 16.17 | 6.042 | 2.000 | 52.67 | 4670 |

| IM | 0.210 | 0.000 | 0.408 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 4707 |

| RDE | 0.025 | 0.021 | 0.027 | 0.000 | 1.040 | 4297 |

| RDH | 15.87 | 12.96 | 12.11 | 0.030 | 87.75 | 2485 |

| HHI | 0.088 | 0.044 | 0.106 | 0.000 | 0.794 | 4666 |

| Variables | MP | VAC | TIC | MC | CS | CA | IM | RDE | RDH | HHI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MP | 1.000 | |||||||||

| VAC | 0.053 *** | 1.000 | ||||||||

| TIC | 0.349 *** | 0.011 | 1.000 | |||||||

| MC | 0.720 *** | 0.055 *** | 0.366 *** | 1.000 | ||||||

| CS | 0.740 *** | 0.058 *** | 0.393 *** | 0.927 *** | 1.000 | |||||

| CA | 0.116 *** | −0.005 | 0.109 *** | 0.209 *** | 0.196 *** | 1.000 | ||||

| IM | 0.032 ** | 0.039 ** | 0.018 | 0.039 *** | 0.065 *** | 0.024 * | 1.000 | |||

| RDE | 0.007 | −0.001 | 0.119 *** | −0.055 *** | −0.096 *** | −0.035 ** | −0.034 ** | 1.000 | ||

| RDH | −0.039 * | −0.007 | 0.122 *** | −0.204 *** | −0.121 *** | −0.079 *** | −0.014 | 0.360 *** | 1.000 | |

| HHI | 0.242 *** | −0.046 *** | 0.122 *** | 0.358 *** | 0.323 *** | 0.060 *** | 0.005 | −0.053 *** | −0.166 *** | 1.000 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | |

| VAC | 0.002 ** | 0.008 *** | 0.375 *** | |

| (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.060) | ||

| VAC × TIC | 0.011 ** | |||

| (0.000) | ||||

| TIC | 0.001 | |||

| (0.000) | ||||

| VAC × MC | 1.822 *** | |||

| (0.292) | ||||

| MC | 0.021 *** | |||

| (0.006) | ||||

| CS | 0.678 *** | 0.017 *** | −0.009 * | −0.000 |

| (0.069) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.007) | |

| CA | 0.088 *** | −0.007 *** | 0.003 ** | −0.008 *** |

| (0.015) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| IM | −0.091 * | −0.001 | −0.003 | −0.001 |

| (0.051) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |

| RDE | 0.301 | −0.070 | 0.009 | −0.079 |

| (0.915) | (0.060) | (0.041) | (0.060) | |

| RDH | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| HHI | −2.097 *** | −0.046 | −0.028 | −0.051 |

| (0.541) | (0.036) | (0.037) | (0.035) | |

| _cons | 2.529 * | −0.223 ** | 0.188 * | −0.278 *** |

| (1.428) | (0.100) | (0.107) | (0.104) | |

| N | 2478 | 2474 | 2401 | 2474 |

| R2 | 0.146 | 0.037 | 0.040 | 0.061 |

| F | 55.879 | 10.676 | 4.156 | 14.101 |

| p | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | M6 | |

| VAC | 0.011 *** | 0.015 *** | 0.003 * | 0.220 *** | ||

| (0.000) | (0.045) | (0.001) | (0.057) | |||

| VAC × TIC | 0.171 *** | 0.161 * | ||||

| (0.000) | (0.011) | |||||

| TIC | 0.002 ** | 0.006 ** | ||||

| (0.001) | (0.004) | |||||

| VAC × MC | 0.314 *** | 2.010 *** | ||||

| (0.002) | (0.302) | |||||

| MC | 0.072 *** | 0.908 *** | ||||

| (0.351) | (0.444) | |||||

| CS | 0.030 * | 1.157 *** | 0.991 ** | 0.682 *** | 1.429 *** | 0.934 * |

| (0.016) | (0.264) | (0.386) | (0.194) | (1.141) | (0.485) | |

| CA | 0.009 *** | 0.179 *** | 0.362 *** | −0.088 ** | 2.846 *** | 0.478 *** |

| (0.003) | (0.066) | (0.053) | (0.042) | (0.283) | (0.067) | |

| IM | 0.012 * | −0.063 | −0.033 | 0.310 | 0.338 * | 0.130 |

| (0.031) | (0.227) | (0.242) | (0.408) | (0.968) | (0.303) | |

| RDE | 0.481 | 1.001 * | 0.044 ** | 9.781 | 0.815 | 0.655 * |

| (0.503) | (0.606) | (0.038) | (6.579) | (0.973) | (0.304) | |

| RDH | 0.023 * | 0.028 ** | 0.309 | 0.001 | 0.005 * | 0.043 * |

| (0.015) | (0.020) | (0.984) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.031) | |

| HHI | 0.224 | −5.207 *** | −4.368 *** | 3.780 * | 0.559 * | −1.486 |

| (0.182) | (1.446) | (1.607) | (2.288) | (6.175) | (2.016) | |

| _cons | −0.191 | −18.307 *** | −6.261 | −11.865 *** | 5.468 *** | 3.661 *** |

| (0.347) | (5.260) | (4.949) | (4.332) | (2.724) | (0.291) | |

| N | 2474 | 2854 | 3146 | 2474 | 2849 | 3139 |

| R2 | 0.185 | 0.338 | 0.341 | 0.142 | 0.103 | 0.353 |

| F | 16.00 | 13.28 | 22.21 | 22.95 | 38.325 | 16.200 |

| p | 0.014 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Quan, H.; Agbanyo, G.K.; Caputo, F.; Chin, T. The Role of Value Appropriation Capability of Chinese Multinationals in Operating Cross-Border Business Models. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9812. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179812

Quan H, Agbanyo GK, Caputo F, Chin T. The Role of Value Appropriation Capability of Chinese Multinationals in Operating Cross-Border Business Models. Sustainability. 2021; 13(17):9812. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179812

Chicago/Turabian StyleQuan, Hanxu, George Kwame Agbanyo, Francesco Caputo, and Tachia Chin. 2021. "The Role of Value Appropriation Capability of Chinese Multinationals in Operating Cross-Border Business Models" Sustainability 13, no. 17: 9812. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179812

APA StyleQuan, H., Agbanyo, G. K., Caputo, F., & Chin, T. (2021). The Role of Value Appropriation Capability of Chinese Multinationals in Operating Cross-Border Business Models. Sustainability, 13(17), 9812. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179812