1. Introduction

The global garment industry has been changing over the years in response to the needs of society and recently also in response to environmental issues. At the beginning of the rapid development of clothing production, the magnitude of the impact on nature was probably not realized. Over time and with the increase in the benefits of a quick response to the fashion needs of customers, the environment has been abandoned. Meanwhile, today, brands face the challenge of adapting to the expectations of a new type of consumer who has greater social awareness and perceives products not only through the lenses of the quality or price but also of the values that they bring. Consumers’ movements trying to persuade the garment industry to introduce the necessary changes in production methods, materials used, or actual control of the supply chain are gaining in importance worldwide. It may be a form of sustainable citizenship in which individuals try to assume social responsibility and meet ecological challenges [

1]. However, these behaviors depend on the consumer awareness, linked to its demographics, including, inter alia, age, ethnicity, and income [

2,

3]. The fashion and notions of sustainability are socially constructed, therefore, in order to understand reality, we need to uncover people’s behaviors in the given context [

4,

5,

6].

The Polish economy has gone through tremendous socio-economic changes over the last 30 years toward the market system. For a long time, the space for the implementation of socially responsible business behaviors has been quite small. The visible degeneration of the business environment at the beginning of the transition and the heritage of the socialist regime (high corruption, obsolete work conditions, very hierarchical work relations, etc.) left very little room for the penetration of Western ideas aiming at improving the quality of business toward sustainable voluntary practices [

7]. Rapidly after the economic transformation, Polish consumers met the phenomenon of fast fashion and entered the phase of hyper-consumerism, eased by the emergence of the local fast-fashion industry and the arrival of the global fast-fashion players.

The long-standing garment industry in Poland is considered very hermetic. Not all clothing sector entrepreneurs are ready to talk about the environmental challenges related to their business [

8]. The scope of change across the sector is still in its infancy, and the concept of sustainable fashion has yet to be popularized [

9]. At the same time, it should be noted that the number of companies aware of the environmental challenges and wanting to face them in a comprehensive manner is constantly growing. Every year, new organizations appear based on sustainable business models. They set trends and show how to find oneself in complex relationships in the supply chain so that the offered product meets not only the quality criteria but also the practical implementation of the principles of sustainable development.

Simultaneously, most of the specialized Polish fashion portals claim that “CSR is no longer a fashion, but a necessity”—is this the reality of Polish fashion consumption? We claim that Polish consumers need some more exposure to the sustainability message spread by the fashion industry, which besides green production and distribution practices should play the role of an educator in sustainability.

The aim of this research is to investigate how Polish fashion consumers approach the concepts of sustainability, such as organic, fair-trade, and carbon emissions. Exploring the experience of the Polish consumption context will provide a richer understanding of the evolution of fashion sustainability concepts in this and similar countries. The research aim is supported by the following question: Is the Polish fashion consumer aware of current sustainability issues and trends? There is no similar academic study so far, and we hope to fulfil the existing knowledge gap with this research. This paper offers an important first academic input into existing empirical evidence on this topic provided by consulting companies.

This paper comprises six logically structured sections.

Section 2 below contextualizes the research, presenting the main argument and briefly reviewing the related literature.

Section 3 describes the research method, while

Section 4, entirely empirical, sets out the results of the numerical analysis.

Section 5 interprets and discusses the outcomes, contrasting them with the other surveys.

Section 6 concludes.

2. Contextual Background

The general philosophy of sustainable development comes down to the reconciliation and combination of the two contradictory concepts of “growth” and “development” into one cooperating whole. The concept of sustainable development proposes a form of conscious, responsible life of individual and social development together with the environment–social, natural, and economic, taking into account ecological limitations and social expectations. It can be said that this idea is understood as a way of conducting further socio-economic development that will not harm future generations and will consider the requirements and laws of nature. In 2015, the need for a very integrated effort for revitalizing and improving the world has been expressed under the SDG goals of the UN Agenda 2030 [

10].

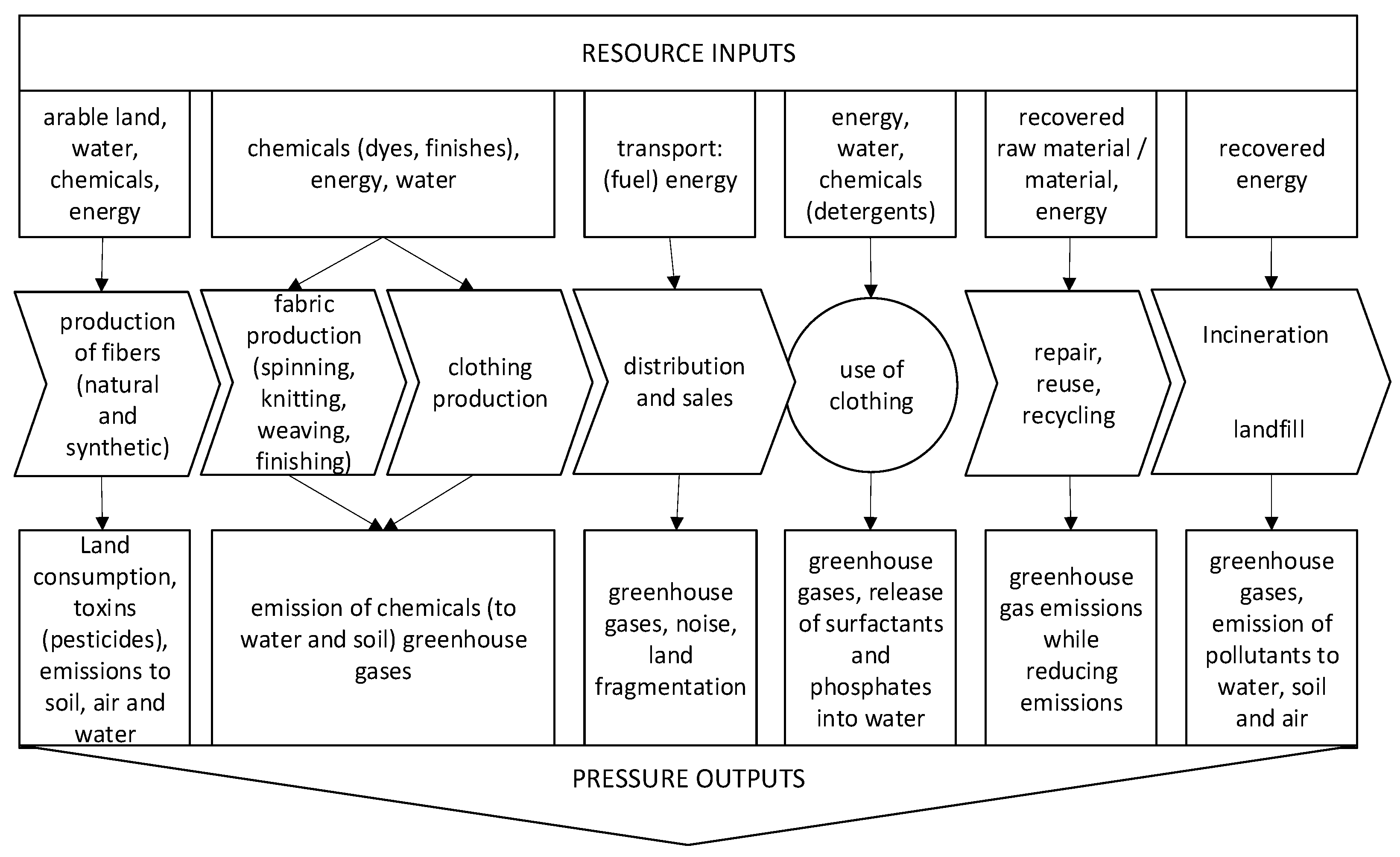

In order to fully understand the challenges of sustainable development in the fashion industry, it is necessary to explain what the fashion industry contains and how much it has changed in recent years. The main branches of the textile and apparel industry are presented below (

Figure 1).

The textile and clothing industry provides a lot of jobs; it employs over 75 million people in the world. About 85 percent of them are women [

12]. For some areas of the world, it is also often the most important sector for generating income and ensuring economic development. This part of the international economy simultaneously generates many financial benefits and struggles with many social problems, in particular bad labour and compensation conditions.

The garment industry is among the five least environmentally friendly branches of the economy [

13]. A structural change within the clothing industry resulted in a shift in manufacturing from the Western world to developing Asian countries in order to achieve lower production costs [

14,

15]. Zara, H&M, and other high-street brands have revolutionised the fashion industry by clinching fast fashion [

16]. This approach relies on a quick response, which results in shortening their lead times to achieve the latest trends for affordable or cheaper prices in the market. With time, the ability to react instantly to current trends has motivated retailers to continually improve their response times [

17]. Thus, the quick reaction formula has resulted in major financial success [

18]. A focus on increased acceleration in manufacturing processes to cut down on response time ended in comprising the price and quality to imitated and low-quality products, which are trendy [

19]. As lead times are shortened, they made this model to witness an increase in trend turnover and over-consumption [

20,

21]. The retailers who do not implement the fast fashion strategy and adapt to the latest market trends have a lower profit growth [

22]. Additionally, with the increase in the production of clothing, the number of times an item of clothing is worn has decreased [

23]. Another important change in this sector is the ongoing digitization of the fashion industry. Digital platforms and digital marketing become very important tools in the hands of the big players on the market but they also enable the emergence and relatively fast growth of new brands [

24].

The changes in clothing shopping habits along with globalisation have played a massive role in apparel overconsumption responsible for heavy environmental impacts [

25,

26]. To analyse the impact of the fashion industry on the natural environment, all stages of the garment’s life cycle should be considered. The life cycle of a clothing product begins with obtaining the raw material and ends with the disposal of the product. A garment that was produced with environmentally friendly raw materials with a harmful imprint applied in the finishing process cannot be called ecological. Moreover, the consumer’s use is included in the product life cycle. The life cycle of a clothing product can be divided into the production phase, the use phase, and the disposal process. The harmful production cycle processes are present at each stage of the production process (

Figure 2).

More specifically, the problems arise from the use of non-renewable resources in different forms along the entire supply chain, especially for synthetic fibres; the use of significant amounts of pesticides and fertilizers when growing natural fibres; the use of hazardous substances and chemicals in production processes, resulting in a negative impact on the environment, employees, and users of the final product; the use of large amounts of water and energy in production processes; generating a significant amount of waste and problems with their disposal; and emissions of pollutants to air, water, and land at all stages of the life cycle of a garment product [

28,

29]. It is important to measure the impact of the textiles and clothing industry on the natural environment in order to take appropriate actions to reduce this impact [

30].

These large clothing concerns that have existed on the market for many years are associated mostly with the fast fashion model. Newly established small brands, which show their activities, often take care of sustainable development from the very beginning. Companies involved in the production or sale of clothing products that want to prove their sustainable approach are often certified. There are many institutions and organizations that provide such certification, which can be carried out, for example, on products, processes, or entire management systems. The most common are GOTS (Global Organic Textile Standard), Fairtrade Certified, STANDARD 100 by OEKO-TEX

®, and Bluesign

® [

31,

32,

33,

34]. On the other hand, brands are often selectively and strategically implementing sustainable practices at different stages of their supply chains rather than overhauling the practices that make the industry so unsustainable in the first place [

35]. This approach often leads to greenwashing.

The growing consumer pressure worldwide is manifested by numerous organizations fighting for a fair approach of the clothing industry to the environment and society. Among the most active, one can find Fashion Revolution or Remake Our World. In addition, these and other NGOs and statistical institutions carry out surveys to diagnose consumer awareness of sustainable development in the clothing industry. These kinds of studies are still scarce in Poland; however, in the last two years, some reports have been released.

Poland is the largest country of the former socialist bloc that joined the EU in 2004. This means that it has, in a sense, been bypassed by the environmental movements that started in the United States in the 1960s and gradually extended to the Western world (Type “Give Earth a Chance”, see [

36]).

Today, the attitude of Poles to climate change is strongly determined by the opinion of people who deny the essence of environmental changes and the very limited ambition of the government in environmental awareness building. The level of knowledge about ecology in Poland is still insufficient. Only 10% of the population assess their knowledge in this regard as very good [

9]. Despite the introduction of further regulations on waste segregation, sorting is declared by only 66% of Poles. When choosing everyday products, such as food or cosmetics, Poles first of all pay attention to the price and composition of the product, then to its impact on health, naturalness, brand opinion, and practicality of the packaging. Ecological issues, including the environmental impact of the product or its packaging, are much less important and are indicated by only a few percent of respondents. For every third Pole, the price of a product is a barrier that prevents environmentally sustainable consumption behavior. The initial desire to buy a product with an ecological certificate drops drastically as its price increases [

37]. Most Poles are not aware of the devastating impact of the garment industry on the environment, presented above.

At the same time, Poland’s fashion market grew by approximately 3% annually between 2015 and 2019 (it saw a 12% drop in sales between 2019 and 2020 due to COVID-19). Despite being valued at roughly €8.2 billion in 2020, the fashion market remains challenging territory for retailers and brands, who must cater to customers who are price-sensitive but also harbor high expectations of quality [

38]. Based on the research by Vogue and BCG (2021) [

39], only 40% of consumers in Poland claimed to buy sustainable apparel. A large percentage of those who did not shop sustainably did not see eco-credentials as important factors in their purchasing decisions (69% of this group) or were put off by doubts about the ethical and environmental impact of brands (42% of this group). Confusion about the quality of sustainable apparel when compared to regular products (38% of all consumers) was also a blocker according to this study. Another survey by Smurfit Kappa [

40] states that the sustainability awareness of Polish fashion consumers was reinforced during the first phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Research has shown that before choosing a brand, 25% of consumers checked the level of its commitment to environmental protection activities on the Internet, 35% of consumers said they would not purchase online from a fashion company if found to be using non-organic packaging for their products, and 23% of consumers surveyed purchased the same fashion brand again thanks to a testimonial about its commitment to sustainability. Both studies emphasize the trend of growing environmental awareness of the Polish clothing consumer. These quite comforting statements are questioned by our research.

3. Research Methodology

Choosing the right tool for this study was quite a challenge. After reviewing the existing studies conducted among clothing consumers around the world, the authors selected a study that has not been carried out in Poland. The idea behind it was to provide a wide field for comparison. The selected study, “Sustainable fashion, a survey on global perspectives”, has been commissioned by Fashion Summit, sponsored by HSBC, and supported by KPMG China. On the basis of this study, our own questionnaire, containing 22 questions (including one, multiple, and Likert-scale choice questions), was built.

The main hypothesis for this research was: Polish consumers are not sensitive to sustainable development in the clothing industry. This statement has been enhanced by the preceding sections, demonstrating a certain backwardness or rather relative ‘unawareness’ of the garment consumers on the Polish market. The survey was anonymous and was conducted using the surveymonkey.com (accessed on 27 March 2021) application. The questionnaire was divided into two sections: the first section contained fundamental questions regarding the consumer’s approach to sustainable fashion, and the second part was devoted to the metrics of the respondents.

Before the questionnaire was sent out, a trial verification of its correctness and understanding had been performed. Three testers stated that they did not understand the term sustainable fashion and that the term should be clarified at the beginning. In addition, two testers suggested a change to the number of ticks in the multiple-choice question, as they felt willing to select more answers than possible. The proposals were considered, and appropriate corrections were introduced.

The responses were collected mainly via social media such as Facebook, Instagram, and LinkedIn. The link to the survey was made available in the form of posts but also sent in a private message. The target research group was randomly selected Poles. The answers were collected between 1 and 30 April 2021. As described below, more women than men decided to participate in our survey, which probably results from the fact that more women are interested in fashion than men.

Altogether, 178 Poles (

n = 178) participated in the survey, including 133 women (75%) and 45 men (25%). The most represented age group are young respondents (18–24). The other demographic characteristics are presented in

Table 1. The results were compiled using the SPSS software.

4. Results

When asked “How often do you buy clothes?”, the respondents most often answered that less often than once in two months (31.7%). The second most frequent response was “once in two months” (29.2%). A total of 17.4% of respondents buy clothes more than once a month, while 16.3% declare buying clothes once a month. Women more often indicated that they buy clothes once or more times a month, compared to men, where most of the surveyed men buy clothes once every two months (41%) (

Table 2).

The next question was about caring for the environment. The vast majority indicated that they do not always care but they try (73%). Almost every fourth respondent (23%) answered that he/she cares about the environment at every possible opportunity. Taking gender into account, women more often than men indicated that they care for the environment at every possible opportunity (

Table 3).

In the next step, our respondents were asked whether they think about the impact on the environment when buying clothes; the majority of the respondents said no (58%). Comparing the responses of men and women, the vast majority of men (82%) and half of the women do not think about the environment when buying clothes. Moreover, it is noticeable that the vast majority of respondents living in the countryside (72.7%) do not think about the environmental impact of the clothes they buy. By comparison, less than half (47.1%) of people living in the largest cities (over 500 thousand inhabitants) do not think about the environment when shopping for clothes.

Table 4 shows the percentage of individual choices made by the respondents.

When asked if they support sustainable fashion, the main groups of respondents replied that they have no opinion (47.8%) or that they support it (47.7%) (

Table 5). More than half of the women replied that they supported sustainability in the clothing industry (53%). In comparison, only 34% of men support sustainable fashion, and not a single man replied that he definitely supports it. Only 2.3% of women and 11.4% of men do not support sustainable fashion.

When asked whether they think that Polish society supports sustainable development in the clothing industry, almost 70% of the respondents said no. A total of 25.8% of the respondents did not have an opinion on this topic, while only 5.7% believed that Poles support sustainable fashion (

Table 6). The gender factors seemed to not have a significant influence on this perception.

The survey also asked consumers which of the following features best define sustainable fashion. The respondents stated that the most suitable feature is production without harmful substances that have a negative impact on the environment. Subsequently, the most frequently marked features were “use of recycled materials” and “second-hand clothing”. Slightly fewer people indicated the feature “packing in biodegradable packaging”. In our respondents’ opinion, the least suitable features for sustainable fashion were “repair services” and “involvement of the local community” (

Table 7).

In the survey, consumers were asked what their willingness to buy clothes from a sustainable source would be, taking into account the price of the clothes. Most of the respondents (67.4%) indicated that they would buy clothes from a sustainable source if the prices of these clothes were similar to normal clothes (standard clothes on the market). A total of 26.4% of respondents would pay more for sustainable clothing. A total of 5.6% of consumers are in favour that the prices of clothes from a sustainable source are lower than the prices of standard clothes on the market. Only 0.6% of the respondents would not buy clothes from a sustainable source (

Table 8). In terms of gender, it can be seen that women are more likely to pay more for clothing from a sustainable source; 31.1% of women chose this option compared to 13.6% of men. Moreover, no woman indicated that she would not buy clothes from a sustainable source, whereas 2.27% of men chose this option.

Quality was a factor that the vast majority of the respondents chose as the answer to the question “What do you consider when you buy clothes/shoes”. The second most frequently chosen answer was price. The size/fit of clothes is also very important for the respondents. Other factors also considered by consumers are fabrics, previous shopping experiences, and style. The least important for consumers are aesthetic packaging, the possibility of personalization, and finally celebrity endorsement (

Table 9).

The question about how much the given factors would encourage consumers to buy clothes from a sustainable source was asked. Each factor was assessed on a scale from 1 to 5. The highest-rated factor was price, and the average rating for this factor was 4.57. Quality came second, with an average rating of 4.5. The fabrics were in third place (rating 4.14). The lowest-rated factor was style (3.78) (

Table 10).

When asked what they would pay more attention to when buying clothes from a sustainable source, more than half (60.1%) chose the product. A total of 32% of respondents would pay attention to both the product and the company/brand from which they buy. A total of 5.1% do not know what they would pay attention to. The smallest number of people would focus their attention only on the company/brand (2.8%) (

Table 11).

The survey asked also whether they think that a sustainability certificate would encourage customers to buy from their store. The results are presented below in

Table 12.

We also asked respondents what they do with clothes they do not want to wear anymore (

Table 13). The vast majority of people (81.5%) donate clothes to charity, 29.8% of the respondents resell them, and 18% of consumers repair or remake them. The lowest number of people (14.6%) throw the clothes away. According to the collected data, women (9.1%) are less likely to throw clothes into the trash than men (31.8%). Moreover, women are more willing to donate clothes to charity (85.65%) than men (70.5%).

When it comes to the question of where the surveyed consumers shop most often, the opinions are divided equally; half of their things they buy online, the other half in-store.

Consumers were asked also how often they considered sustainability in the garment industry when purchasing garments in the past. Most people (57.9%) answered rarely, while 12.4% of respondents always considered sustainability when purchasing. The answer “never” was selected by 29.8% of the respondents. Among women, 16.7% always considered sustainable fashion when shopping, while men rarely thought about it. As many as 47.7% of men and 23.5% of women did not consider sustainability challenges in the clothing industry at all (

Table 14).

Next, the respondents were asked about their opinion on difficulties in purchasing clothing from a sustainable source. A total of 46.1% of respondents believed that it is neither difficult nor easy. A total of 42.2% of consumers believe that they find it difficult to find clothes from a sustainable source. Many fewer (11.8%) respondents believed that it is easy to buy such clothes.

Table 15 below shows the described data.

The last question in the study was open-ended. It concerned the knowledge of the Polish fashion brand that consumers associate with sustainable development. A total of 73% of the respondents replied that they did not know such a brand. Among those who responded, there were foreign brands such as Patagonia, Jack Wolfskin—a German clothing producer, and the French chain of Decathlon stores. Among the Polish brands, the following brands were mentioned most often: Elements, Nago, The Other Side, Eppram, and Balagan. In addition, the respondents mentioned companies such as Ecoalf, Yes to Dress, Medicine, Łyko, Naoko, Koko World, Pulpa, King of Indigo, Mud Jeans, Gau, Wearso, Lemiss, Patrizia Aryton, RISK made in Wrasaw, Hibou, Talja, Wasala, Asin, and the brands of the Polish group LPP.

Comparing the above-presented results with the findings from KPMG study, there are some significant differences to highlight. First of all, Poles are not as declared supporters of sustainable fashion as the representatives of other surveyed markets; only 47.7% of Poles support the sustainable approach in the clothing industry, compared to 90% of those in Shanghai, 71% in Hong Kong, 54% in New York, 54% in London, and 49% in Tokyo. Poland is also the worst, in comparison to other markets, when asked about the respondents’ opinion on their society’s approach to sustainable fashion. Only 5.7% of interviewed Poles claimed that their society supports sustainable development in the clothing industry, while as many as 77% of surveyed consumers in Shanghai consider themselves to be part of a society supporting sustainable fashion; the same opinion is shared by 43% of Hong Kong residents, 36% of Tokyo residents, 34% of New Yorkers, and 25% of Londoners.

When ranking the features defining sustainable fashion, Poles prioritized production without harmful substances having a negative impact on the environment. The second most frequently chosen feature was the use of recycled fabrics, and the third was the use of second-hand clothes. In the markets surveyed by KPMG, high-quality and long-life clothes were most often chosen on average, followed by the non-use of environmentally harmful chemicals and ethical and fair trade/employment. As far as the prices of clothes from sustainable development are considered, 26.4% of Poles would pay more for clothes from a sustainable source, which is the highest result compared to the surveyed markets. A total of 22% of Shanghai consumers indicated that they would pay more as well as 15% of New York respondents, 13% in London, 8% in Hong Kong, and 6% in Tokyo.

In the surveys, consumers were asked what features they take into account when buying clothes. In all locations, respondents ranked price, size/fit, and quality in the first three places. For comparison, we asked which features would encourage people to buy clothes from a sustainable source. Here, Polish consumers chose the price, quality, and fabrics in the top three places. Consumers from Hong Kong and Tokyo had the same opinion. Londoners and New Yorkers put price, quality, and style in the top places.

The research asked what they would pay attention to when buying from a sustainable source: product or brand. The responses in all surveyed markets are very similar. The majority of consumers would pay attention to the product. On a question about the encouraging effect of the sustainable certification of fashion brands, Polish consumers place themselves in between other societies (65.2%), with 81% for Shanghai, 73% for Hong Kong, 58% for London, 56% for Tokyo, and 53% for New York. Among the countries surveyed, Poles throw their clothes in the garbage the least (14.6%) and donate the most (82%) to charity. In the other surveyed markets, an average of 39% of consumers throw their clothes into the trash and 37% donate to charity. As many as 29% of Polish consumers declare reselling clothes, which is a relatively high score compared to the other surveyed markets (10% on average).

Polish consumers of clothes do their shopping just as often online as in stationary stores. Only in Shanghai do consumers do shopping online (56%) more often than in-store. Among people who think that purchasing from a sustainable source is difficult, the percentage of Poles is the highest (46%). On the opposite side of the scale are the consumers in Shanghai who believe that it is rather easy.

5. Discussion

The fast-changing consumer dynamics towards sustainable fashion are visible in most of the countries. Poland is not an exception; however, due to its relatively young free-market experience and also very short, and poorly supported by decision-makers and national media, exposure to the challenges of climate change, it may be considered an interesting market for this kind of analysis. After this research was achieved, a few other reports appeared focusing on sustainability in the fashion industry in Poland. Therefore, our aim in this section would be to discuss our findings in the light of the empirical outcomes of the recently published reports, mostly by Vogue and BCG (2021) [

33], by Accenture and FashionBiznes.pl, together with the content partner of the Responsible Business Forum (2020) [

9] and the above-mentioned source report by KPMG (2019) [

39].

The study commissioned by Accenture and FashionBiznes.pl showed the characteristics of consumer behaviour in the field of ecological fashion and readiness for sustainable consumption models. According to the findings of this study, 42% of respondents stated that it is difficult to indicate what is most lacking in the pro-ecological activities of clothing manufacturers, footwear, and accessories related to fashion. In our study, we asked them to rank characteristics of sustainable fashion, and the production process appeared at the top of the list along with the use of recycled fabrics. According to our findings, only 5.7% of interviewed Poles claim that their society supports sustainable development in the clothing industry. This very critical appraisal of their compatriots is supported by findings of the other above-cited reports.

Polish fashion consumers buy clothes most often for practical reasons, and Generation Z and the people who spend the most on clothing buy clothes more often because of new trends and style. Our research places quality, price, and size/fit at the top of the features of clothes considered when shopping, which confirms to some extent the practical motives of the Polish consumers. Additionally, only slightly more than half of the clothes are worn regularly. Consumers do not read labels; they cannot indicate what their clothes are made of (24%), and they are confusing the country of origin of the brand with the country of manufacture. Simultaneously, they declare readiness to buy products with ecological ingredients that are even more expensive if the higher price will go hand in hand with the high quality of the product. Meanwhile, the survey by the Vogue-BCG found that a majority of the consumers (51%) asked for lower prices of sustainable apparel. All the studies confirm that Polish consumers sometimes throw away or destroy their clothes (our findings confirm this fact at 14.6%), but they often pass them on to others, which is part of the concept of sharing economy (81.5% according to our findings). This may be the result of a fairly important network of used clothing customers in Poland, including a dense distribution of collection containers. Consumers like to buy in second-hand shops (38%); they are also curious about new shopping models, especially rental companies. Moreover, they do their shopping just as often in online as in stationary stores.

Our research asked what they would pay attention to when buying from a sustainable source, product, or brand. The responses in all surveyed markets were very similar- the majority of consumers would pay attention to the product first. Consumers have quite a limited knowledge of the existing new, often entirely sustainable, Polish brands; 75% of the respondents were unable to give one single name. This and some other above-presented findings confirm that the knowledge about sustainable fashion is still negligible, and the discussion on this topic has not yet been conducted on a large scale and become firmly established in public opinion.

6. Conclusions and Limitations

The aim of the study was to identify the approach of Polish clothing consumers to sustainable development in fashion. The outcome showed the attitude of Polish consumers and the differences in opinions and attitudes between Poles and their counterparts from compared markets. According to our findings, Polish consumers declare caring more about the general environment but do not pay attention to sustainable development in the clothing industry. It is also observable that Poles have an unfavourable opinion of their own nation regarding its approach to sustainable development in the clothing industry. At the same time, Poles seem ready to pay more for a garment from a sustainable source. Moreover, Poles eagerly donate their clothes to charity, throw them into the trash less frequently, and repair clothes more often than the other markets. In addition, respondents declare not considering sustainable development when purchasing in the past. Unfortunately, a large proportion of Poles also find it difficult to buy clothes from a sustainable source. Surprisingly, they are not aware of the existence of the sustainable clothing brands in their market. Considering all that, the hypothesis put forward in the study was confirmed in the responses and opinions of our respondents.

It is important to emphasise that the scope of change across the clothing sector in Poland is still in its infancy, and the concept of sustainable fashion has yet to be popularized. According to numerous reports, Poles do not feel responsible for the products used; they believe that the greatest responsibility for recycling lies with whoever produced a given product or packaging. Meanwhile, responsibility for the environment and society is a joint task of companies/producers and consumers. It will not be possible to effectively implement the necessary changes without the appropriate knowledge and leadership of companies, which themselves face a number of challenges, including introducing circular economy standards, measuring and reducing the negative impact on the environment, ensuring appropriate working conditions, and implementing transparent rules for communicating changes to the environment and consumers. This change is ongoing; based on the review of companies’ performance towards sustainability in recent years, it can be inferred that this awareness of both companies and customers will increase in the near future. As part of their marketing and corporate social responsibility practices, clothing companies can start educating Polish society. The COVID-19 crisis, which definitely enhanced the management of large fashion companies worldwide to start following a greener path [

23], might also have an impact on customers’ behaviours by making them aware of the importance of limiting the consumption of goods, including clothing. This trend will certainly apply to Polish brands and consumers as well.

In conclusion, it is important to declare that authors are aware of the shortcomings of this study, which in turn offer avenues for future research. First, the sample has been randomly composed and is relatively small. In consequence, the number of male and female respondents was not equal, and there is a visible predominance of relatively young people. Furthermore, considering these weaknesses, we could only test the sustainable fashion attitudes in general and from the gender perspective. Therefore, it requires further deeper verification and appraisal, preferably using an entirely self-constructed questionnaire and a greater sample, enabling more accurate findings, taking into account other socio-demographic factors.