Abstract

Understanding the factors affecting the policy process of quality assurance is important for assessing the development of higher education. Here, we used a qualitative research approach, along with an analysis of policies and a literature review, to investigate the national policy process. The factors of quality assurance relating to improving the quality of higher education and SDGs in Thailand since the introduction and implementation of a national policy on quality assurance between 1999 and 2019 were also analyzed. Content area experts in Thailand were directly interviewed, and the obtained data were analyzed in terms of the Act. Through the analysis, we identified three main processes affecting education quality assurance between 1999 and 2019; namely, policy formulation, policy implementation, and policy evaluation. Our findings reveal that, although the policy was defined as an act during the policy formulation process, its implementation and evaluation have been limited by critical factors, such as the achievement of graduates, university ranking, and the country’s competitiveness. We conclude that prioritizing the quality assurance policy and facilitating relevant factors are essential to improving the development of higher education in Thailand.

1. Introduction

Previous studies have suggested that a strong relationship between education and poverty paves the way for the development of the population, households, communities, and social orders. Additionally, low levels of education and poor aptitude procurement hamper economic growth, thus preventing poverty reduction (McNamara, P. et al., 2019) [1]. Education adds to the development of equity and reduction of destitution. Education provides individuals with knowledge and abilities, which fosters the reduction of income inequalities, allowing individuals to learn and develop aptitudes that improve their efficiency and make them less vulnerable to risks. It has been calculated that one year of education increases wage income by 10% (Montenegro, C.E. and Patrinos, H.A., 2014) [2]. On the other side, impoverished individuals are often powerless against adverse events occurring in adulthood. The quantity of extreme climate events and other natural catastrophes—including storms, floods, droughts, earthquakes, and landslides—is expected to rise in the near future (Lutz et al., 2014) [3]. However, equitable education expansion can decrease income disparities (Abdullah et al., 2015) [4]. Accordingly, “Education for All (EFA)” was proclaimed by the World Education Forum (WEF) in Dakar, Senegal, at the 2000 follow-up to the emerging Sustainable Development Goals (proposed in May 2015). The UN consented to have the full result of the WEF as Goal 4 for the agenda 2030, which had been the broadest and most profound ever, with respect to education policy. At the higher education level, universities have a unique position in society. There are wide variations in the world, and the dissemination of universities has served as a driving force in both global, national, and local innovation, economic development, and social welfare aspects. As such, universities play a critical role in the achievement of and engagement with the SDGs. Universities have a role in educating about, innovating, and solving the problems of SDGs, creating current and future SDGs, developing systems, and demonstrating how to support bringing the SDGs to corporate governance and cross-sectoral cultures; overall, leading the way towards answering the SDGs (UNESCO, 2017) [5]. The ability of a university to recruit participants involved in future revenue and success in the labor market, provide better quality training, and better network access has been well-documented (Douglas, W., 2014) [6]. In addition, the SDG Index and Dashboards Report 2017 introduced the overall Sustainable Development Goals Score Index. The 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were ranked and divided into three key indicators for each target: good, medium, or poor. The report found that, although Thailand is ranked 55th out of 157 countries overall, when considering the sub-metrics from a total of 83 data sets collected, the performance indicators can be classified as consistent with the SDGs: The results were 34 good indicators, 29 moderate indicators, and 18 poor performance indicators, while two indicators were not available. For the SDG Goal 4 “Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all”, the net primary enrollment rate should be 98.1%, the lower secondary completion rate should be 78.4%, and the literacy rate should be 98.1% (Sachs, J. and Schmidt-Traub et al., 2020) [7]. Expanding tertiary education may promote faster technological catch-up and improve a country’s ability to maximize its economic output (Bloom, D.E., Canning, D. and Chan, K., 2006) [8] A one-year increase in education resulted in an 11% increase in income, and the private institutes average global is 9% a year (George, P. and Harry A.P.). The return on investment for social rate is 16% in low-income countries (Pradhan et al., 2018) [9] (2018) [10]. However, the quality of higher education has been shown to be a particularly vicious problem, involving policy-making, and debate over the quality of higher education has led to efforts to determine the effects of such a complex issue; in particular, relating to dealing with the nefarious problems posed by external factors such as economic growth, knowledge, rapidly changing academic work environments, diverse student groups with changing needs and expectations, and governmental action agendas that define institutional funding and reputation (Krause, 2012) [11].

Regarding the importance of higher education, the growing demand for it, and educational quality issues, a revolution in the quality of higher education, called the quality revolution, has expanded over the last three decades (El-Khawas, 2013) [12]. Quality assurance is indispensable for developing higher education, providing a policy tool for bringing insights (Neave, 1998) [13]. The quality of higher education increases student learning outcomes and promotes economic development (El-Khawas, 2013) [12]. Quality assurance policies also encourage students and parents to invest in the quality of education (OECD and UNESCO, 2005) [14]. Quality assurance also promotes responsible practice in the use of public and private funding (Stenstaker and Harvey, 2010) [15]. In addition, the impact of international standards has been increasing in this era of globalization, as well as the need for transparency and public accountability. This is a new challenge for higher education, which requires a strong quality assurance system (Salmi, J. et al., 2002) [16]. For all of these reasons, models of educational quality assurance have been posed, such as European models, the United States model, and the British model. Since the end of the 20th century, every country in the world has made efforts to comply with quality assurance processes and standards, which form part of the field of basic quality assurance (Wells, 2014, p. 21) [17]. Therefore, new public policies regarding quality development have been integrated into the policy of many countries (Dill and Beerkens, 2010) [18]. Many of these countries have formulated national policies to enhance the quality of education. To guarantee the quality of education, the policies and procedures involved must contribute to the development and continuous improvement of quality. Quality assurance in higher education in Thailand started as a policy in 1999, under the National Education Act, and has been updated thereafter through three legislative acts. Before it was launched, internal quality assessment mechanisms were created for the preparation of future quality assurance, using the index of Chiang Mai University as a guideline, in 1996 (Working Group on Educational Quality Indicator Development, 1998) [19], which were addressed in the National Education Act 1999. Recently, after two decades under its enforcement, the results of the Act remained below those expected. In particular, a low score was obtained for the quality assurance system, while access and sustainability scores were very high (British Council, 2016) [20]. Moreover, Thailand’s education system still remains at a junction. As the nation intends to move past the middle-income trap, it must fabricate a highly skilled workforce. The huge venture has broadened access to education, and Thailand has been shown to perform moderately well in global assessments, in contrast to similar countries. Be that as it may, the advantages have not been generally circulated, and Thailand has not gotten the return on its investment in education that it may have anticipated. Furthermore, an excessive number of factors, which are vital to the achievement of the minimum standards needed for full participation in society, have been neglected (OECD/UNESCO, 2016) [21]. While educational quality assurance tools can be used effectively around the world, Thailand, which has used education quality assurance policy for more than twenty years, requires an explanation of which processes need to be improved, what factors are involved, and why only Thailand has experienced this unsatisfactory result. Consequently, the discussion of reforming higher education has led to it being considered as a high priority for the government and universities, with a focus on the quality of instruction and learning (which do not identify with the real situation), and the development of the country.

For this need, policy initiatives of educational quality assurance can provide a solution, as the role of government is not only to provide education but also to consider its quality, which has become a major dimension of higher education (Hazelkorn, E., 2016) [22]. Public policy is the governmental mechanism driving the achievement of a country’s goals and its development. Regarding the main process—policy formulation, policy implementation, and policy evaluation—governments can formulate policies through analyzing problems, the related factors, the policy windows, and design. The policy implementation process can facilitate decisions on how to assign the related government bodies, as well as how to distribute and deploy the supported resources through Acts and/or laws. The policy evaluation process can provide the framework to monitor, conduct, and measure how much it has achieved. For this reason, the development of a country depends on the quality of the decision-making policy framework and the involved processes (Corkery and Bossuyt, 1995) [23]. In many cases, it has been found that policies designed to implement educational change for improving quality have often failed, due to a lack of understanding of the complexity of the context and the system. Analysis of the policy process, including policy formulation, implementation, and evaluation, can demonstrate the required administrative approaches, the expansion needed at each level, the factors influencing the policy, and determine the appropriateness of the policy process (OECD, 2015) [24]. While there has been a significant increase in research on the quality of education, at the same time, there have been very few studies considering the educational policy process in Thailand, although there is a high public awareness of the development of educational quality, from which it is recognized that this policy and legal framework can have a profound impact on the quality of education at both national and local levels. Therefore, research inquiring into the system and analyzing it pragmatically can be considered very useful in bringing about the form of public policy process for quality assurance in Thai higher education. The purpose of this article is to examine how the national policy process of higher education quality assurance has driven the quality cycle and what the related factors are. Furthermore, the objective of this article is to guide policy-makers and stakeholders in making choices regarding educational reform. Although this study is based on an in-depth study only at the national policy level in Thailand, the results may raise some interesting variables and policy recommendations, which might be useful for countries with similar conditions. In addition, this could be an interesting case study, which could lead to the development of national higher education quality assurance policies and international cooperation networks.

2. Overview of Higher Education in Thailand

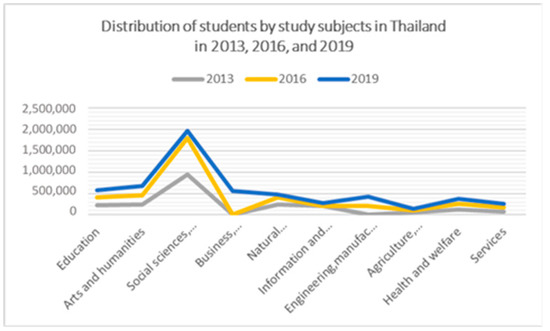

In 2018, there were 155 higher education institutions under the Office of the Higher Education Commission, with 24 autonomous universities; 10 public universities; 38 Rajabhat universities (the institution of higher education that was originally established for the production of teachers. Currently, there are comprehensive universities in the group focusing on producing undergraduate students); 9 Rajamangala universities (the institution of higher education that was originally established for the production of engineers and technicians at the vocational level and higher education. Currently, there are comprehensive universities in the group focusing on producing undergraduate students); Technology institutions, colleges, and universities; 1 community (20 campuses distributed throughout Thailand); and 73 private institutions. There are also higher education and academic institutions that are specialized in higher education under the Ministry and other departments of the Commission on Higher Education (Office of the Education Council, 2018) [25]. The number of students in higher education was 1,790,341 in the academic year 2016. The graph below (see Figure 1) shows the ratio of the largest student population, which has been the same for a decade in the fields of humanities and arts, and social science and business; where law accounts for more than half (57%) of the student population in Thailand and exceeds science and technology (incl. engineering; almost 40%). The country’s goal is to develop in line with the Industry 4.0 paradigm.

Figure 1.

Distribution of students by study subjects in Thailand in 2013, 2016, and 2019. Source: Office of the Education Council (2018) [25].

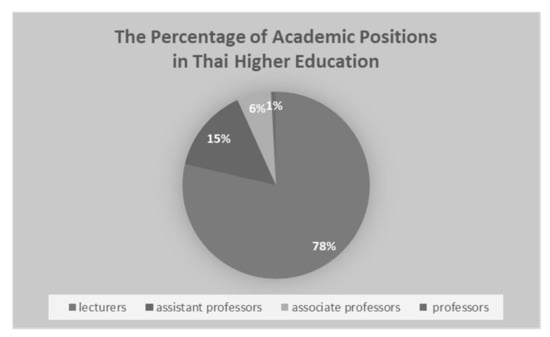

There were 95,527 Thai academic faculties in higher education throughout the country, of which 35,742 were autonomous universities, 17,491 in public universities, 1438 in autonomous universities, 7423 in Rajamangala University of Technology, 578 in community colleges, 12,660 in private universities, and 1011 in private institutions (OHEC, 2017) [26]. Of all these faculty members, only 1% were full professors (see Figure 2). In this regard, this may be an important factor in promoting the quality of education at the higher education level.

Figure 2.

Percentage of academic positions in Thai Higher Education faculties. Source: Office of the Education Council (2018) [25].

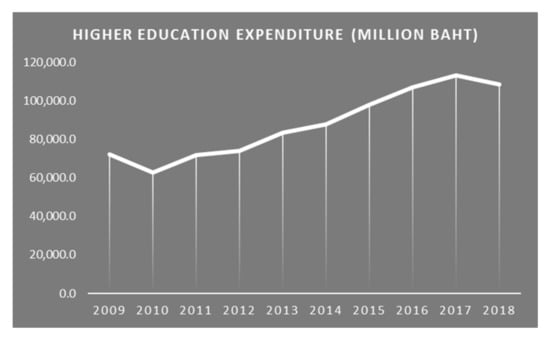

The education budget increased by 50.35% in 2018, compared to 2009 (when it was 72,058.6 THB). The average rate of increase in the education budget was 5% per year over the 8 years. However, an investigation of the composition of the expenditure in the higher education budget revealed the operational budget expenditure was 91%, while 9% was the investment budget. Although it seems that the budget for higher education has continued to increase (see Figure 3), the budget has almost all been allocated to manage the operations, which cannot push the higher education sector to keep up with changes in the global market.

Figure 3.

Higher Education Expenditure from 2009–2018 in Thailand. Source: Office of the Education Council (2018) [25].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. An Analytical Framework for the Policy Process

The study of policy processes is generally divided into policy studies and policy analysis. Policy studies are studies regarding knowledge of the policy process. Descriptive approaches are mainly used when considering the policy process, policy outcome, and policy evaluation, while policy analyses focus on knowledge in the policy process for policy evaluation, data analysis for decision making, policy recommendations, and assessment of policy adoption (Peters, B.G. and Hogwood, B.W., 1984) [27]. The policy process is becoming increasingly complex, as driven by the increasing number and diversity of relevant policy-makers who are linked together in the policy network (Rhodes 1997) [28]. Lasswell (1956, 1971) [29] described that “cycles” and “stages” have been embedded in policy analysis studies. The seven-stage policy process model includes intelligence-gathering, promotion, prescription, invocation, application, termination, and appraisal, which should be a cycle to complete when implementing any public policy. In addition, Brewer (1974) [30] presented a five- or six-stage model (invention/initiation, estimation, selection, implementation, evaluation, and termination). In addition, three scholars with different focus have considered policy processes in depth: First, Howlett, M., Ramesh, M. and Perl, A. (2009) [31] focused on the methodology at each stage of the policy process; while E.S. Quads (1984) [32] focused on comparing, evaluating, and forecasting policy alternatives that will impact the future; and, finally, Simon discussed policy analysis methods. However, in this paper, the concept of Howlett, M.; Ramesh, M.; and Perl, A. was applied, for reasons of consistency with the purposes of the research. Furthermore, the methodology used in this study is based on the concept of Christopher, A.S. [33], who used the method of studying public policy in historical analysis by studying the processes related to solving past policy problems. We used interview methods for each policy section, as well as document analysis, to discuss issues that may be behind the scenes, yet result in the policy being successful or failing.

There are also scholars in Thailand who have studied the public policy process. S. Yawapraphat and P. Wangmahaporn (2009) [34] have divided the public policy process into three sub-processes: policy formulation, policy implementation, and policy evaluation. This is in line with the findings of international scholars, and in accordance with the context for the analysis. However, it is clear that no frameworks exist. In theory, the policy process is self-explanatory. Indeed, a multi-framed approach is better, where different perspectives can be layered to form a broader explanation (Cairney and Heikkila, 2018) [35]. In the concept of Kingdon’s Three-Stream Model (1984) [36], policy change occurs when three streams—problems, political issues, and policy issues—are connected. Kingdon’s model suggests that, while the three streams may operate independently, all three need to come together to formulate a policy. The “Formation of Problems” and “Policy Flows” can be defined in terms of the following: (1) Problem streams refer to policy issues in society that may be a problem; (2) Policy flows involve many potential policy solutions emerging from the community of policymakers, experts, and lobby groups, referring to factors such as changes in government. Laws and the volatility of public opinion lead to a mixture of “Problems” and “Politics”, creating open opportunities for policy operators to seek appropriate policy changes. Public policy-making is part of the pre-decision-making process in the policy setting, including targeting, priority, and assessment of the cost and benefit options for each of the external options. This involves identifying a set of policy options and public policy tools to address the problem at hand. This model seems to fit well with the issue of coverage of educational policy, as included in the streams. In line with this area of focus, three theorists have jointly contributed to our key framework for analyzing the three stages of the public policy process: the concepts of Anderson (2011) [37] and Kingdon (1995), regarding the public policy process and policy windows, are applied for reasons of consistency with the aim of this paper, while the methodology of Simon (2017), using historical and literature analyses, as well as an interviewing approach, is utilized to determine any underlying issues that have led to policy success or failure.

3.2. Interviews of the Content Area Experts

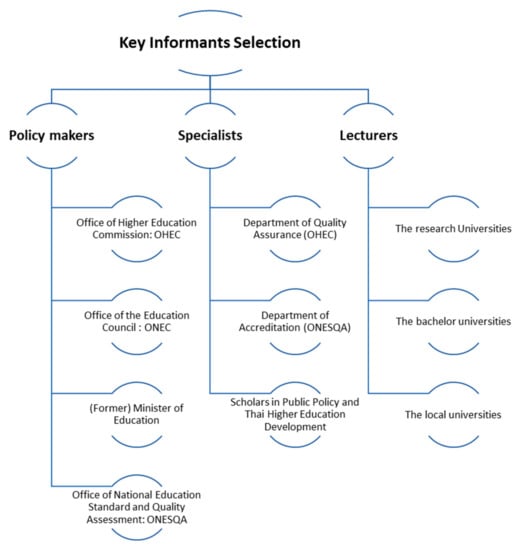

The first of the two approaches considered herein is a review of the existing literature and policies. We draw on previous and current studies, formal and informal policy documents, and texts published in the written press. The second approach follows a qualitative data collection method, through the use of oral interviews with the content area experts (CAEs) who possess inside knowledge and, so, could analyze and interpret issues in the related field (Gøtzsche, P.C. and Ioannidis, J.P.A., 2012) [38]. The researchers designed the study while respecting the standard procedures and approval processes of the committee of the Department of Development and Sustainability, Asian Institute of Technology. The interviewees included three groups involved in the policy process cycle, whose expertise was considered outstanding and who had lengthy experience in the field, including policy-makers, agencies, specialists, and lecturers. Overall, 25 CAEs were consulted and interviewed for this study. Their selection was made according to four characteristics: (1) having a national position; (2) involved in a wide national policy on quality assurance; (3) belonging to an organization related to the effects resulting from the policy; and (4) having knowledge of the existence of actions resulting from the policy. Qualitative structured interviews were conducted with the 25 CAEs. The interviewees involved in three stages of the policy process included government officials, experts in the field, and lecturers, (see Figure 4) as detailed in the following.

Figure 4.

Key informants at various levels selected for the interviews.

- Group I: Policy-makers

This research is a national policy study. Policy-makers involved in Thai national quality assurance policy-making were considered to possess key knowledge for answering our research objectives relating to the three public policy processes (i.e., policy formulation, policy implementation, and policy evaluation). Besides, the factors that lead to the success or failure of the higher education quality assurance policy are related to those policy steps and, finally, the recommendations for the development of educational quality assurance policy for Thailand.

- Group II: Agencies/Specialists

Agencies are directly responsible for quality assurance policies in higher education. For this group of contributors, a very important group of agreements has been studied by UNESCO. This unit will be able to address the issue of quality assurance in higher education. In this research, three important issues are identified: accreditation, external quality assurance, and internal quality assurance. This group of experts was considered to be one of the most important groups in the research, who can answer the objectives of the research in its entirety. As experienced performers in all three parts, being policy-makers or politicians, policy leaders, and practitioners (e.g., as representatives or personnel in higher education institutions), they may also be involved in assessing and implementing quality assurance policies at the national or international level. This can be used to analyze the processes that drive the quality assurance policy, further leading to an analysis of the link to the factors that affect the success or failure of the development of higher education in both countries.

- Group III: Lecturers

Lecturers form the group who are directly involved in the quality assurance of higher education. This group becomes involved by being part of the agency boards, which are responsible for formulating the quality assurance policy and the associated criteria, where the implemented criteria should be consistent with the guidelines and the developed framework. Therefore, this group is directly involved, and was considered to be able to answer the research question very well.

A structured interview, following a set of prescribed questions relating to the study objectives, was conducted for this study. The information obtained from the structured interview questions can be compared between each interview. Therefore, the themes and patterns may be generalizable to others (Johnston, D.D. and Vanderstoep, S.W., 2009) [39].

For the policy-makers, the research questions were as follows:

- (1)

- Public Policy Process of Higher Education Quality Assurance

- 1.1

- What is the main objective of quality assurance in higher education?

- 1.2

- How is the decision-making process for the policy formulation of quality assurance in higher education?

- 1.3

- Which organizations are responsible for the policy process for higher education quality assurance both in the policy-making process? Implementation of the Policy and policy evaluation

- 1.4

- What is the process for implementing the educational quality assurance policy?

- 1.5

- How is the higher education quality assurance policy evaluation process?

- 1.6

- What is the process for developing policies/systems for quality assurance in higher education?

- 1.7

- What level was the achievement of the quality of higher education in the past?

- (2)

- Public policy procedural factors affecting the success of educational quality assurance in higher education

- 2.1

- Policy formulation process of higher education quality assurance: How does it affect the success or hinder the development of the quality of higher education in Thailand?

- 2.2

- Policy implementation process of higher education quality assurance: How does it affect the success or hinder the development of the quality of higher education in Thailand?

- 2.3

- Policy Evaluation Process of Higher Education Quality Assurance: Does it affect success, or is it an obstacle to the development of the quality of higher education in Thailand?

- (3)

- Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Obstacles of Higher Education Quality Assurance Policy in Thailand: What are the main points of each process?

- (4)

- Policy Recommendations on Higher Education Quality Assurance for Thailand

For the Agencies/Specialists:

Public Policy Process of Higher Education Quality Assurance

- What are the main objectives of the Higher Education Quality Assurance Policy in Thailand, and what should they be?

- Systems and mechanisms for driving educational quality assurance policies in higher education

- 2.1

- How important is the government’s role in the policy of improving the quality of higher education?

- 2.2

- What laws and regulations are important mechanisms for driving quality assurance in higher education?

- 2.3

- What role does NESDB play in the higher education quality assurance system and the development of the higher education quality assurance system in each policy process?

- 2.4

- What role does the university play in the policy process for higher education quality assurance and the development of higher education quality assurance policies in each policy process?

- 2.5

- In addition to the above, what other stakeholder groups are important to the higher education quality assurance policy process?

- 2.6

- How effective is the policy implementation process of the Thai educational quality assurance system? Are there any obstacles?

- 2.7

- How effective is the policy evaluation process of the Thai educational quality assurance system? Are there any obstacles?

- Factors Affecting Success of Quality Assurance in Higher Education

- 3.1

- How does the policy formulation process of higher education quality assurance affect the success or hinder the development of higher education quality in Thailand?

- 3.2

- How does the policy implementation process of higher education quality assurance affect the success or hinder the development of higher education quality in Thailand?

- 3.3

- How does the policy evaluation process of higher education quality assurance affect the success or hinder the development of higher education quality in Thailand?

- How does quality assurance affect success? Is it an obstacle to the development of the quality of higher education in Thailand?

- What is your view on the achievement of the quality of higher education in the last ten years?

- How has the process of developing educational quality assurance policies in higher education changed from the past to the present?

- What are the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and obstacles of the Thai higher education quality assurance system in each process?

- Policy Recommendations on Higher Education Quality Assurance for Thailand

For Lecturers

Public Policy Process of Higher Education Quality Assurance

- What is your opinion on the quality of higher education in Thailand, compared to other ASEAN countries?

- Have you seen the effect of the higher education quality assurance process in Thailand since the promulgation of the National Education Act B.E? What are the advantages or limitations?

- What suggestions do you have for developing an educational quality assurance system at the higher education level as a tool to support the development of higher education quality in Thailand?

Participants were contacted by email and telephone, after which a face-to-face semi-structured interview was conducted. During the interview, participants were asked to reflect on the questions and participate in the assessment of their responses to the questions and related topics. The interviews were later transcribed verbatim for analysis, and a codebook was developed. The authors created a preliminary code set, then encoded the data through a process similar to open cryptography (Strauss, 1987) [40]. Grounded theory was used in the data analysis (Strauss and Corbin, 1998) [41]. Initial analysis identified three categories, consistent with Kingdon’s theory. Through further workshopping, several sub-themes were identified within each category. Linkages and connections between sub-themes were developed, and a matrix was created, which combined Kingdon’s initial streams with more nuanced sub-themes. The analysis of data focused on finding consistent themes throughout most of the interviews related to the research questions (see Table 1). The study provides substantial descriptions of individual cases, analyzing the relevant documents while also seeking to demonstrate general themes among them (Merriam, 1998) [42].

Table 1.

Matrix of the research framework (author).

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. The Policy Formulation Process: The Rationale behind the Policy Process and the Establishment of Quality Assurance Policy

The policy process concepts of Anderson (2011) and Kingdon (1995) were applied to analyze each sub-process; that is, formulation, implementation, and evaluation. Beginning with the formulation process, public policy is a policymaker’s decision, resulting from the interaction of many powerful factors (Peters, 2007) [43], and which has a political context that has a profound effect on the public. Furthermore, social contexts and cultural factors lead policy-makers to have different views, thus affecting the overall decision-making process. In this paper, influencing factors are divided into external and internal factors.

4.1.1. Factors Affecting the Policy Processes of Educational Quality Assurance

External Factors

In the two decades prior to the 1999 Education Act, of which quality assurance was a part, globalization was an important driving force in the creation of an increasingly borderless world. This factor has led to an increase in the awareness of country-level development, especially with respect to education. In accordance with Kingdon (1995), the concept of policy windows states that policy formulation begins with the problem stream considered by the public. This sentiment has been reflected in the country’s report, as follows:

“The country’s geographic, economic, and political conditions were suitable for being developed as an educational center in Southeast Asia. It was the duty and responsibility of higher education sector to be a center for human resource development”.(NESDB, 2002) [44]

“The World Bank and UNESCO have played important roles in determining Thai education policies. However, the policy making process in Thailand did not completely follow the theory of global convergence by globalization and can be called partial convergence of policies”.(Pholphirul, P., 2005) [45]

Internal Factors

The political events in May 1992, calling for democratic reform and renouncement of the country’s leader by the people, resulted in the appointment of a Constitution Drafting Committee.

Section 81 of the 1997 Constitution states that

with respect to the basic right to education.“The state must provide education, training, and support for the private sector to provide education for the knowledge and morality, provide the law on national education. Improve education in line with economic and social change, enhance knowledge and raise awareness about politics and democratic governance with the King as Head of State, support research in various arts and sciences, develop science and technology for national development, professional development of teachers, and promote local wisdom, arts and culture of the nation”,

Further, Section 43 states that

“The right to public education by providing equal rights and opportunities to receive basic education for not less than 12 years. The state must provide thorough and quality without incurring expenses.”

The policy guidelines for the expansion of basic to lower secondary education were established in the 7th National Education Development Plan (1992–1996) and later extended to the upper secondary level, as specified in the Educational Development Plan, Issue 8 (1997–2001). This included the implementation of the project to expand opportunities for education at the lower secondary education level by the Department of General Education, The Ministry of Education, which started its operation in 1987. The project aimed to raise the basic knowledge of the people to the secondary level, by aiding disadvantaged people—especially those in rural areas—to attend school. This resulted in an increased demand among lower secondary school students to seek higher education (NESDB 2002) [44]. In the 7th National Educational Development Plan (1992–1996) and the 8th National Educational Development Plan (1997 and 1998), the number of high school graduates in the school system (both general and vocational) increased from 237,679 in 1992 to 468,847 in 1998, which increased the demand for higher education (NESDB 2002) [44]. However, considering the data of students who had the opportunity to study in higher education institutions, it was found that, among the upper secondary school students, only 11% from farming families had the chance to attend higher education. High school students also had to compete in various systems to enter higher education institutions. There was a wider call for opportunities and equality, in terms of access to higher education (Ministry of University Affairs, 1996) [46].

The massive economic crisis in late 1997 affected Thai society, causing high levels of unemployment and unrest, and affected the education budget of Thailand for the first time (NESDB, 2002) [43]. Several problems with the Thai education system have been debated, both before and after the passing of the 1999 Act, which focused on four themes (each aspect is addressed in this study). It seems that the major problem in the Thai higher education system is the quality of graduates. This, in part, is a consequence of the huge expansion of the system that occurred during the 6th Economic and National Development Plan. An absence of modern curriculum development is another concern. The curriculum and the teaching processes in higher education institutions are outdated, with a focus on one-way teaching, memorizing, and modular manner teaching, rather than encouraging students to learn systematically. Teaching skills such as the English language, computer usage, and management are low, compared to other countries in Southeast Asia (Ministry of University Affairs, 1996) [46].

Addressing the manpower shortage in science and technology, mathematics, computational chemistry, dentistry, and pharmacology, due to an increase in student numbers, is a problem. The quality of graduates was affected, as the existing number of lecturers and their qualifications were insufficient. There was also a brain drain to the private sector, due to the higher remuneration offered. Some lecturers, not wishing to teach large learning groups, chose early retirement (Ministry of University Affairs, 1996) [46].

Thai people had a lower education rate at all levels in 1997, compared to South Korea, consistent with the Bureau of Statistics survey in 1999. According to the survey, among the Thai population aged 13 years and over, 48 million were educated at primary and lower elementary education (i.e., 68%), while only 14% had attended upper secondary education and 6% had attended tertiary education (National Statistical Office, 2017) [47]. People have demanded equal opportunities in higher education (Ministry of University Affairs, 1996; Office of the Permanent Secretary, 2016). More than 50% of higher education institutions affiliated with the Ministry of University Affairs were in Bangkok and its periphery. A total of 31 out of 52 universities in the country were located within this area, although higher education institutions affiliated with the Ministry of Education were distributed in the regions as follows: Bangkok, 13%; Central region, 28.33%; North, 20%; northeast, 28.3%; and southern region, 17.09%. Between 1987 to 2006, many higher education institutions were established, due to the government increasing funding in different regions of Thailand.

In the past, the education system of Thailand was controlled by a bureaucratic system. Although a human resource management system was introduced in 1980, the problem remained. At that time, two main departments were responsible for higher education: The Ministry of University Affairs and the Ministry of Education. The incorporation of ministries without adjusting their management system influenced the administration. Therefore, the universities were independent, and the role of the Ministry was focused on supervising higher education institutions.

There were also problems with the performance evaluation system. The educational management was ineffective in monitoring and evaluating policies, linking with auditing and evaluation systems, and lacked in information exchange and the sharing of audit results. Moreover, the organization responsible for the audit also lacked the operational capability of both personnel and academic budget. It is necessary to have a structuring budget and effective assessment systems, including internal and external quality assurance, training of personnel to meet standards, and establishing a process for implementing assessment results to improve the quality of education in each academic year. This resulted in an inability to evaluate the results of policy formulation or solve administrative problems. This education issue resulted in many problems, such as poverty, unemployment, drugs, crime, or national security, among others. A need arose for the development of a quality assurance plan and better education management system, in order to develop the education system and to enhance the nation’s economy. The National Education Act 1999 was an important development, which changed the existing system. The Act sought to ensure that everyone received quality education. To facilitate this, the education system had to be transformed to enable students to learn by themselves, and every part of society was to be equipped with educational institutions. This factor was a crucial aspect, which is mentioned in the analysis session.

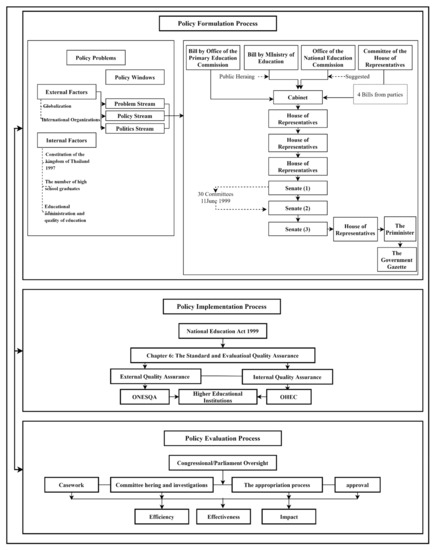

4.1.2. Agenda Setting and Policy Analysis

Regarding all of the above aspects, the need for educational reform was so intense in Thai society that many bills were drafted by different organizations. Thereafter, the bill was passed in accordance with the procedures of the constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand in 1997. The bureaucratic system affected the improvement of the quality of education by focusing on reform, which falls into the sector of educational quality assurance. There was an organizational structure, and a new organization (ONESQA) responsible for external quality assurance was established, with duties relating to creating assessment criteria to determine the direction of the principles of quality assurance. Stakeholder groups were identified by studying the public policy formulating process for educational quality assurance in higher education in Thailand (see Figure 5). Their roles and importance are discussed below.

Figure 5.

Summary of Thailand’s public policy processes of quality assurance in higher education. Adjusted from Kingdon (1995) [36] and Anderson (2011) [37].

Civil servants were important actors in the drafting of the National Education Act 1999. The Act was drafted by the bureaucrats of the three organizations who brought three bills to the parliament, with the approval of the Cabinet (Secretary-General of the House of Representatives 1999) [48].

According to the Ministry’s revised Act of 1991, the Ministry of Education had authority in education, religion, and culture. The Ministry of Education was responsible for managing and providing educational services to the public, in accordance with the National Education Plan, including pre-primary education, primary education, secondary education, vocational education, teacher training, education, special education, and adult education. In the making of this educational bill, the Ministry of Education implemented the Bill with 14 other government departments.

The Education Commission had a mission to contemplate and propose the National Education Plan, the National Education Development Plan, and the Educational Policy Guidelines to the Cabinet. It also had to coordinate the operations of educational arrangements and the development of the ministry and related agencies. The National Education Bill of the Office of the National Education Commission had the Deputy Prime Minister as the chairman, along with experts and scholars from various fields. It also heeded to public opinion. As a result, this draft was considered by the House of Representatives.

Politicians were important players in the national education policy formulation process through the National Education Act 1999. The legislation was drafted by four political parties (Secretary-General the House of Representatives, 1999) [48]. The process for considering the bills was undertaken thereafter.

The Education Council used research as a basis for drafting the law. In this draft, the organizer invited experts to conduct research on 42 topics. The consultative meeting process for researchers presented findings on research issues—considering both existing operations and international guidelines—including the results of various research projects of the Education Council itself, with a panel of legal experts. However, the process was carried out primarily by government agencies, either the National Education Commission or the Ministry of Education.

Civil society organizations, such as the disabled association and the Islamic Committee of Thailand, also participated in drafting the 1999 Act. In early January 1998, a brainstorming session involving 60 people took place in Bangkok, with similar events taking place in four regions in the third and fourth weeks of January 1998. A series of surveys were conducted. The first two surveys were held between 10 May and 2 June 1998 and consisted of 12,978 people. The second took place between 18 June and 9 July 1998 and involved 10,486 people. The groups participating in the survey included the Primary Teachers Association of Thailand, the Council of Parents and Teachers of Thailand, The Council of Disabled Persons of Thailand, Private Education Organizations, and the Central Islamic Committee of Thailand. (Secretary-General of the House of Representatives, 1999) [48]. The private sector was also involved in the Bill, through the appointment of private organization representatives to the drafting committee by the Ministry of Education. The mass media also participated in the drafting of the National Education Act.

4.1.3. Policy Design

The design process for tertiary education quality assurance began with a consideration of the teaching objectives. Thereafter, there was a need to decide the type of quality assurance system to use and the appointment of the organization that would be responsible for it. In the successive events, it was decided that ONESQA and OHEC would be responsible. The decision-making process for policy formulation used a conceptual framework and the process for the quality assurance policy was divided into two steps. The first step involved the House of Representatives, whereas the second involved the Senate. The consideration of the Act by the House of Representatives consisted of three steps and, at the end of those steps, the law was agreed upon. A similar process of policy evaluation, after the implementation process determined by agencies and related organizations, was then used in the Senate, which is shown in the chart below (Figure 5).

4.2. The Policy Implementation Process: Deployment within Regulations and Agencies

4.2.1. Legal Mandate

After the National Education Act 1999 was announced, in the Royal Gazette (on 19 August 1999), it officially became law. Chapter 6 comprised the first establishment of “Standards and Educational Quality Assurance”. The “top-down” approach (Hill and Hupe, 2003) [49] could clearly analyze this phenomenon. The law enforcement had employed all the responsible bodies. The table below summarizes this relevant law (see Table 2).

Table 2.

The National Education Act 1999, as well as other relevant laws and updates of quality assurance policy [50].

4.2.2. Actors in Policy Implementation

The Office of the Higher Education Commission (OHEC) is the primary agency responsible for higher education institutions in Thailand, through supervising and monitoring internal quality assurance. Internal quality assurance is the creation of systems and mechanisms for the development, monitoring, and evaluation of higher education institution operations following the policy. Goals and quality levels are set under standards set by the institution or the agency. The jurisdiction of the department and the educational institution have set up the internal quality assurance system of the school, and consider that the internal quality assurance is part of the educational management process to be carried out on a continuous process. The annual internal quality assessment report is submitted to the Council, institutions, affiliated agencies, and related agencies for consideration, and disclosure to the public for improving the quality and standards of education and to provide support for external quality assurance.

The major duty of this committee is to establish a quality assurance system, including determining the indicators and criteria for quality evaluation that are appropriate for the faculty and university. A quality assurance system must link the quality of work from the individual, curriculum, and faculty levels to the institutional level. Creating a quality manual at each level may be necessary, in order to supervise the operation. This committee or department must coordinate and push for an efficient database and information system, which can be used simultaneously at all levels.

Higher education institutions must self-assess, according to internal indicators and quality assurance criteria for every academic year, at the program, faculty, and institution level. The Institute for Higher Education appoints the evaluation committee and sends the evaluation results to the Office of Higher Education Commission, through the database of quality assurance (CHE QA Online; http://www.cheqa.mua.go.th/ (accessed on 23 December 2017)). In the process of assessment, one quality assessment committee may evaluate more than one course, if it is a program in the same subject; such as the same program at the undergraduate and graduate levels.

The Office for National Education Standards and Quality Assessment (a Public Organization) is the main unit responsible for external quality assurance, by assessing the quality of education and monitoring and examining the quality and educational standards of the universities. Regarding the objectives, principles, and guidelines for education at each level, the National Education Act 1999 Amendments (Version 2) 2002 stipulates that every institution must undergo an external quality assessment at least once every five years and should present the assessment results to relevant agencies and public.

4.3. The Policy Evaluation Process: The Parliament Review and the Outcome of 20 Years

4.3.1. The Evaluation Process

To assess “the effectiveness of a public policy in terms of its perceived intentions and results” is the aim of policy evaluation, as defined by Gerston (1997, p. 120) [51]. In the evaluation of any public policy, in addition to assessing the outputs, outcomes, and impacts of a policy, a very important stage is the assessment of the policy process. In a parliamentary democracy, the process for evaluating policies takes place in parliament. Since the enactment of the National Education Act “Educational Quality Assurance”, “Quality of Education” has been mentioned 17 times in parliamentary meetings: Once in 2003, once in 2005, once in 2007, once in 2013, once in 2014, twice in 2015, eight times in 2016, and twice in 2017. The process of reviewing the educational quality assurance policy consists of assessing the philosophy and objective of the quality assurance, system/format/tools/indicators, structure/resources, and guidelines/proposals for the improvement, regulations, the system, the reorganization of the responsible agency, as well as the amendment of the new National Education Act, which also changed the essence of educational quality assurance. A Chairman of the Commission was Recorded in the Report of the study review of the educational quality assurance system, according to the National Education Act, Agenda 4.2 B.E. 2542, 20 February 2003. They discussed the quality assurance policy as follows:

“Since the promulgation of the National Education Act in Chapter 6… When it began to come into effect, there has been a lot of awareness, but amidst that awareness, there has been some confusion in the spirit of providing quality assurance. Still do not understand the system and methods.”

After the higher education quality assurance policy was enforced, the policy faculty reviewed and encountered obstacles to implementing the policy, particularly regarding systems, assessment processes, and criteria used in educational quality assurance. A member of the National Reform Steering Assembly Committee said, in the Minutes of the National Reform Steering Council Meeting No. 13/2015, 22 December 2015:

“Problems arise from inconsistent and inflexible indicators, excessive documentation workload, poor quality of assessors, and poor quality of assessments. Document-based assessment methods, including improperly developed systems for reporting information on the assessment report. The desired image comes after the assessment system reform. That is, the school quality assessment system uses the internal quality assessment of the school as the main unit of assessment for quality improvement. The central external educational institution quality assessment system is only an optional unit.”

Furthermore, there are inadequate and unequal resource and financial barriers among educational institutions, in terms of the management of learning and facilities, which are essential elements of educational enhancement. One of the members of the National Reform Council, in the Minutes of the Meeting of the National Reform Council No. 56/2015 28 July 2015, said:

“Rajabhat University must sympathize with the university called close to the people. Besides, it was able to develop a lot of provinces, but the cost, whether it was the acceptance of students, and the budget was less, how would the quality of education compete with the universities near Bangkok. This is the inequality in allocating the fiscal budget”

The committee, at the policy evaluation stage, studied guidelines for the development of the educational quality assurance system, such that education can be managed following the quality assurance philosophy. Regardless, it is a systematic aspect that should facilitate a quality culture through a wide range of participation. Competent assessors should have an understanding of the resources that should be sufficient for development. A Committee for National Reform Steering Assembly said, in Agenda 3 of the Report of the National Reform Steering Committee on Education on the Reform Plan of the Educational Quality Assurance System, 21 June 2016:

“The method for assessing educational quality should be a kind of visitation and should be so that educational institutions can develop themselves to the highest ideology they want to be. Most importantly, it must be the characteristics of helping create a quality culture in the education system and enabling all parties involved. Especially those who assessed that the quality assurance of education is not a burden but is necessary to improve the quality of education. The supervisions do not have to conduct quality assessments within the educational institutions, but rather serve to support, aid, and budget to provide educational institutions with strong internal quality assurance and readiness to request external quality assessments.”

4.3.2. The Outcome of Higher Education Development System in Thailand

In 2019, eight Thai universities were ranked by QS University Rankings and 14 universities were ranked by the Times Higher Education Ranking (see Table 3). The same number of universities were ranked as in the previous year in the former, but the Times Higher Education Ranking increased the number of universities in the ranking. However, in the QS University Rankings, the overall rank of Thai universities had gone down. When comparing rankings in Asia between 2018 and 2019, Thai universities received better rankings by QS University Rankings, while the rank of Thai universities had gone down in the Time Higher Education Ranking. It has been found that this was due to the internal processes of these universities, in their efforts to establish performance indicators for lecturer evaluation and annual compensation, in relation to the index of world-class and international universities and high-quality education. The assessed criterion is that the professors must have published research papers or international publications.

Table 3.

Higher Education Ranking in Thailand. Source: QS University Ranking Asia (2019) [52], Times Higher Education Ranking Asia (2019) [53].

From the analysis of the quality of higher education in Thailand, the ranking of the institutions of higher education, and the competitiveness of the country itself, it was found that higher education in Thailand is not at the worst level, but it also reflected that there had been no improvement in quality, even though the educational quality assurance system was adopted in 1999.

Higher education in Thailand has contributed to driving sustainable development, through the implementation of various missions and through related networks, such as Engagement Thailand (EnT), Sustainable University Network (Thailand), and The Global University Network for Innovation (GUNI), which has been supported by UNESCO. Many Thai universities have made efforts towards achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In this regard, the five universities that performed well are ranked in the table above (see Table 4). Only two of the universities are globally ranked, while three are ranked in the ASEAN region, although many have made efforts to start pushing forward within the SDG framework. Moreover, only Khon Kaen University was ranked in SDG4.

Table 4.

Thai higher education and sustainable development. Source: Time Higher Education Ranking [53].

The level of competitiveness for each country around the world is published regularly. Reports rank countries by the International Institute for Management Development (IMD) and the Asia–Pacific region Competitiveness rankings (IMD) 2011–2018 indicated that Thailand is ranked 27–30. It has ranked 28th, on average, since 2011, with alternating rankings each year. Rankings for other countries in the ASEAN region include Singapore, with the average ranking 3rd; Malaysia, ranked 17th; Indonesia, 41st; and the Philippines 42nd, as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Competitiveness rankings (IMD) [54] by countries of the Asia Pacific region, 2011–2018.

In addition, the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report (2008–2009 to 2017–2018) found that Thailand, on average, ranked 35th, and was also ranked, according to the following factors: Basic requirements (44th), Efficiency enhancers (39th), Technological readiness (69th), Innovation and sophistication factors (49th), and Innovation (57th) as shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

World Economic Forum [55] Global Competitiveness Report: 2008–2009 to 2017–2018.

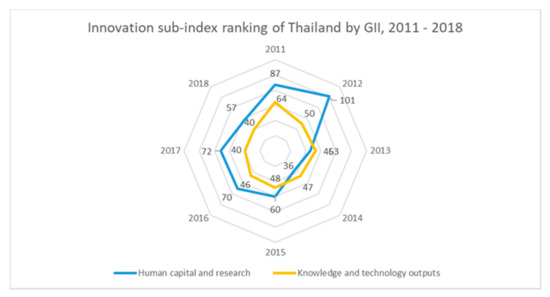

Moreover, the data from the report of the innovation sub-index rankings of Thailand in GII (2011–2018) (see Figure 6), especially concerning higher education in Thailand (i.e., Human capital and research, and Knowledge and technology outputs), has continuously developed with a better result in both factors, where the Human capital and research ranking increased from 87th in 2011 to 57th in 2018; while Knowledge and technology outputs increased from ranking 64th in 2011 to 40th in 2018, as shown in the chart above.

Figure 6.

Innovation sub-index ranking of Thailand (GII, 2018) [56].

The decision-making process for the establishment of tertiary education quality assurance policies was part of the educational reform in 1999. At that time, there was a clear indication that the educational reform would have to guarantee that teaching and learning must have quality standards. Therefore, there exists a framework for the idea that quality education must be provided throughout the whole system. Reform of the educational quality assurance system is the fastest and least costly method, compared to other practices. It also provides the basis for formulating educational policies. The educational quality assurance system has been used for over 20 years in Thailand, leading to several questions and concerns. Since the beginning of the 21st century, countries worldwide have made efforts to comply with quality assurance processes and standards. Although Thailand has had a quality assurance policy for more than 20 years, the quality of education is not as expected. Therefore, an analysis of factors related to the effectiveness of the policy was deemed necessary.

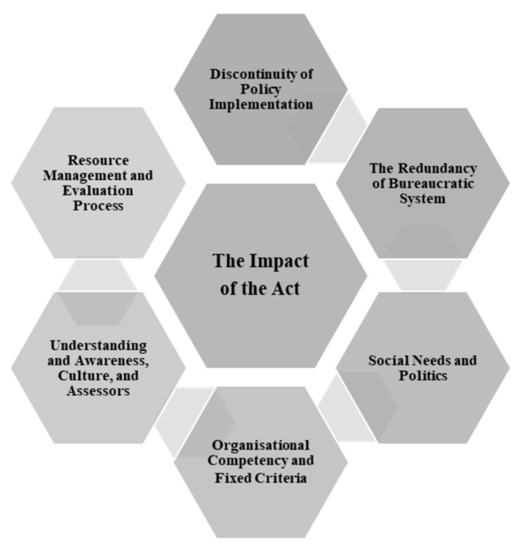

4.4. Analysis of Critical Factors Involved in the Quality Assurance Policy

4.4.1. The Impact of the Act: The Change in Educational Structure

The policy-making process of educational quality assurance and the associated policy formulation—especially at the statutory level in the National Education Act 1999—affects all driving factors of the related organizations and the educational environment. ) (see Figure 7) Creating an organization such as ONESQA and its departments in OHEC has directed responsibility for external and internal quality assurance through a law that provides the power to support operations as an important condition of successful policy implementation, in line with many other countries, such as Japan (NIAD-UE), New Zealand (NZQA), Ireland (QQI), and so on (MoE, 2009) [57]. The role of universities in this legal framework was to attempt to organize a mechanism for educational quality assurance, through the development of a formal structure for a specific internal department and the appointment of a committee for the operation. Furthermore, it also created a perception of change, by raising awareness of the importance and benefits of educational quality assurance for academic and support personnel. The structural changes at all universities, in terms of the organization of their responsibilities for educational quality assurance, are reflected in the following statement by the Director of the Office of Higher Education Commission:

“After the National Education Act of 1999, the Ministerial Regulations were issued, under the principle that the university or educational institution has an internal quality assurance system, with the juristic person being the administrator. Those universities or educational institutions must have a self-assessment report every year, sent to the jurisdiction for the agency to perform the analysis and consider which part of the agency is responsible for promoting. At the same time, this self-assessment report will also be sent to ONESQA as well.”

Figure 7.

Factors influencing the policy process relating to higher education quality assurance.

4.4.2. Discontinuity of Policy Implementation: An Incompleteness of Quality Cycle

A change in educational policy has a big impact on the direction and continuity of the entire process. Once a policy has been established, a period must be taken to investigate the consequence of that policy. Over the past two decades, the educational quality assurance policy of Thailand has often changed at the highest level, and the term “reform” has been used to indicate changes. Therefore, the directions, goals, and indicators had a profound adjust on the policy implementation process, resulting in interruption of the policy. The policy-making process is a key factor in the success or failure of policies (Do, H., 2012) [58], and factors that lead to effective implementation are the motivation and participation of various actors. In Thailand, it has been shown that a small number of people were involved in the policy formulation process. It is based on a culture of political participation. Although Thailand changed to a democratic regime in 1932, the process of transferring power to the people is still not going well. Political contributions and policymaking are often only carried out through elections. Much of the public hearing process was a process that was established only to “follow” the form of the constitution; voices and public opinion were not truly included in the existing draft. Likewise, the majority of instructors were not involved, while groups such as OBEC, the Council of Education, the Ministry of Education, or the Office of the Education Commission were the main groups consulted for policy-making and top-down services. Therefore, these policies may not reflect the opinions and needs of these people, as an interview with a Development Study scholar has highlighted:

“Having educational policies that frequently changed from the upper level when it was set to put into practice was often new ideas, new frameworks, and new indicators. Besides, while the operations were within the framework of the plan and were expected to perform well, it had been found that there had been further changes to the policy at the top level, affecting the policy implementation process. On the other hand, it can be said that we may not be able to infer previous policy failures, but because of incomplete policy processes.”

4.4.3. Redundancy of the Bureaucratic System: Inefficiency of the Administration Process

The first supervisory organization of higher education in Thailand was established as a ministry named “university affairs” with bureaucratic administration, in 1972. Until 2002, country-wide universities were encouraged to be independent and function with full academic freedom. Higher education was managed by a system that was believed to reduce bureaucracy. A new unit, called the Office of the Higher Education Commission (OHEC), was then established. Over the period spent under the new system, the administration and the government remained the same. Recently, universities all over the country have been made to function under the new ministry, called the Ministry of Higher Education, Science, Research, and Innovation. This is highlighted in the following interview from the Executive of Educational Council of Thailand:

“Over the past 7 years, 155 for higher education in Thailand, there are 20 of them in the big universities that do not choose the criteria of the OHEC, but the rest of them use the criteria according to OHEC, most of them are public universities. There’s a bureaucratic, gradual change, not requiring sudden changes that put the burden and exhaustion on themselves in the same environment in the comfort zone.”

Due to frequent coups in Thailand, many government agencies have been established with centralized power. This large structure of the bureaucratic system has affected the efficiency of public administration in Thailand. Therefore, more government agencies have expanded, resulting in redundancy in operations, operational goals and indicators overlapping, continuation of the policy implementation process, and lacking productivity, among other factors. Consequently, it has affected the efficiency and effectiveness of the policy. A senior lecturer in Public Policy supported this, stating:

“When there is a coup, the people who take power have their frameworks for the administration of the country, especially those in the state security that the needs of the people may be in the latter, especially when: The needs of the people go against the peace of the country. And the bureaucracy is larger than the elected democratic government.”

4.4.4. Social Needs and Politics: Mismatching of the Policymakers and the National Plan

From the presented graph (Figure 1), it can be observed that the number of graduates produced in various disciplines across the country is not consistent with the needs of society, stakeholders, and guidelines of national development plans, which intend to direct the nation to be an industrial society. While the students in Social Sciences, Business, and Law subjects comprised 66%, Humanities and Art subjects comprised 13%, Education and Teaching subjects comprised 9%, Science subjects comprised 9%, and engineering were 11%—of which the targets of national development (i.e., into a new industrial age) included a total of 20%. Furthermore, Agriculture, which is considered to impart structural strength to society, had a total of 3%. Only 6% of students were in the area of Health, while Welfare had only 6%; finally, Service Studies—one of the country’s main sources of income—had only 5% of students.

Instead of leading all mechanisms to reach the vision of the national plan, the frequent changes of the ministry not only led to policy discontinuity, but an effort towards centralization by establishing the ministry to supervise the universities was the wrong direction to create varied and effective academia. A scholar in a university stated:

“Shifting the external quality assurance unit “ONESQA” to be under the Ministry of Education reducing the independence in educational management. The teaching and learning management of local educational institutions should tend to provide education by giving the locals more power in the provision of education, for example, to give the curriculum 70% central consideration, 30% local. Moreover, in the period of the coup, more centralize powers were reflected in the form of amendments to textbooks or courses responding to the needs of the security policies.”

4.4.5. Organizational Competency and Fixed Criteria: Inequality of Thai Higher Education Institutions

There are obstacles to using the same standard evaluation criteria for all universities, as each university has different access to resources and disproportionate support from the state. This inevitably affects the success of the implementation of this policy. Our observations suggest that many institutions need governmental support in finance, technology, personnel, and so on, in order to secure the provision of education in line with the quality assessment criteria. However, without sufficient support, these allocations have resulted in low quality assessment scores. When assessments reflect poor performance, but the problem is not addressed, it becomes a cycle that cannot lead to the development of quality education; as a broad member of ONESQA said:

“The key issue discussed is quality assurance models that use the same standards for all universities, but Thai universities have different forms and objectives including a high limited level of freedom to the university.”

4.4.6. Understanding and Awareness, Culture, and Assessors: The Lack of Quality Intention

The top-down educational quality assurance policy has changed frequently in the last 20 years, affecting the understanding of the purposes of quality assessment and educational quality assurance processes. At first, the understanding of educational personnel was that it was an assessment of quality certification, which is only one of six primary objectives. The evaluation process also focuses on documentation, reports, and evaluations to achieve high scores, which are not part of building quality education. When some higher education institutions want to achieve a high score, they try to select assessors in the same group and do not choose a variety of assessors, which is against the principle, as An Executive of the Educational Council of Thailand mentioned:

“The examination of the standard criteria is the authority of the OHEC, but the approval of the course and the examination is the authority of the University Council. The problem is that many teachers still do not understand the standard criteria and course specifications. Therefore, enforcement is a matter of officials.”

One of the key issues at the center of the educational quality assurance process is “quality culture”. While the higher-education atmosphere wants to create such a culture, in order to facilitate the sustainable quality of the system, the atmosphere of Thai higher education is surrounded by a culture of reconciliation and the ally system, which does not benefit the process of reaching the expected standards. A lecturer from a university in Thailand reflected this point, as follows:

“The educational quality assessment system in Thailand seems to be dominated by Thai culture, whether it is a patronage system or a compromised culture. A culture of empathic assessment and the emphasis on passing scores of assessments rather than development approaches. In such a culture, the personnel of the higher education institutions themselves cannot see the direction of development.”

Moreover, the relationship between the assessors and the universities established in each assessment cycle, in addition to establishing a support system, is also based on a document-based assessment. Both of which could complement each other, but not at all favorable to the quality system. A lecturer from a university in Thailand also raised this issue, as follows:

“One limitation of the education quality assurance system is that the system which is focusing on document reviewing. The system that emphasizes document examination is, in principle, unable to reflect 100% of the actual situation, and another important limitation is to allow higher education institutions to elect directors for auditing as well. This can create too much of a relationship in the host system and a judicial process, making the quality of the audit so flexible that it may be less realistically reflective than it should be.”

4.4.7. Resource Management and Evaluation Process: Wrong Direction and Inappropriate Administration

There is a tendency for continued investment in higher education, as can be seen from the data presented in the previous section; however, the majority of the budget ended up being allocated to operational expenditures (90%). These expenditures are not linked to the educational quality assurance system, leading to the goal of improving the quality of graduates. The process of developing the components of educational quality assurance linked to the development of the quality of teaching and learning has been defined in the indicators of educational quality assurance, which imply that a course teacher must have academic credentials, environment, and educational equipment that support teaching and the learner’s skill development. These important factors are supposed to be evaluated in the educational quality assurance system, but the results of the assessment do not lead to the allocation of funds to procure the equipment and facilities required for the development of quality education.

In the evaluation of any public policy, in addition to assessing the outputs, outcomes, and impacts of a policy, a very important stage is the assessment of the policy process. In a parliamentary democracy, the process for evaluating policies takes place in parliament. Since the enactment of the National Education Act “Educational Quality Assurance”, it has been discussed 17 times at the Parliamentary meetings: once in 2003, once in 2005, once in 2007, once in 2013, once in 2014, twice in 2015, eight times in 2016, and twice in 2017. These dates and the frequency of the discussions are important to note because, in the 20 years of the use of the term “educational reform”, there has been very limited discussion about quality assurance in education. This shows the very low importance given to educational quality assurance by policy-makers. If this continues, it is unlikely that education quality will undergo the expected development. Public policy, including the development of education quality, has not been evaluated as it should have been.

4.5. Interpreting the Findings

Having summarized the policies on higher education quality assurance in Thailand in brief, and placing them in their social and political contexts, we are also able to participate in a more systematic comparison and reflection of our findings within the context of the related literature. This study is one of the very few that examines all three parts of the policy process, including the factors affecting it and its effects. However, after reviewing many studies, we found that there has been a strong emphasis on the policy formulation process. Policy formulation is an important step in the policy process, which is a clear issue in policy design, a critical process. Many scholars have argued that the main cause of policy success or failure is due to policy design influencing policy outcomes (Do., H., 2012) [58]. Through the use of policy tools, the government also gains an important factor for enhancing policy formulation (Howlett and Ramesh, 2003) [59]. In addition, the policy formulation process requires the motivation and involvement of different actors, with the entrance of new performers and new ideas playing a real role in the process. The starting point is the analysis of fundamentals of good policy-making, including clarity of goals, an open and evidence-based concept, rigorous policy design, external involvement, thorough assessment, and clarity of the role of the central government in establishing effective mechanisms (Hallsworth, M. and Rutter, J., 2018) [60] In line with a study on the failures in education policy, our findings indicate the failure of educational standards and low quality in the implementation of ineffective education policies, largely due to failures in the policy-making process. These failures include a lack of indigenous education policies, lack of an adequate action strategy, lack of participation of stakeholders (especially teachers) in the policy-making process, lack of continuity of policy implementation, and a lack of political will. Similar disparities have also had a serious impact on the implementation of education policy, thus affecting the standard of education in Nigeria. (Oyedeji, S.O., 2015) [61].

In accordance with prior studies, which relied exclusively on the system and measurement of the policy process and quality assurance, the quality assurance mechanism plays a crucial role in developing the quality of education: not only is the structure of the framework improved in terms of each function of the system but also awareness is raised, and the surrounding ecosystem is enhanced, thus becoming more relevant and effective. As such, Russian higher education has been integrated into The European Standards and Guidelines (ESG), having a powerful impact on the enhancement of the Russian state accreditation system, which was initially provided to set up quality assurance systems (Gevorkyan and Motova, 2004) [62]. Thereafter, ENQA has had a significant effect on the formation of the Russian quality assurance system, making it more obligatory, more transparent, and raising great public awareness (at all levels) regarding the national education system (Motova and Pyykkö, 2012) [63].