1. Introduction

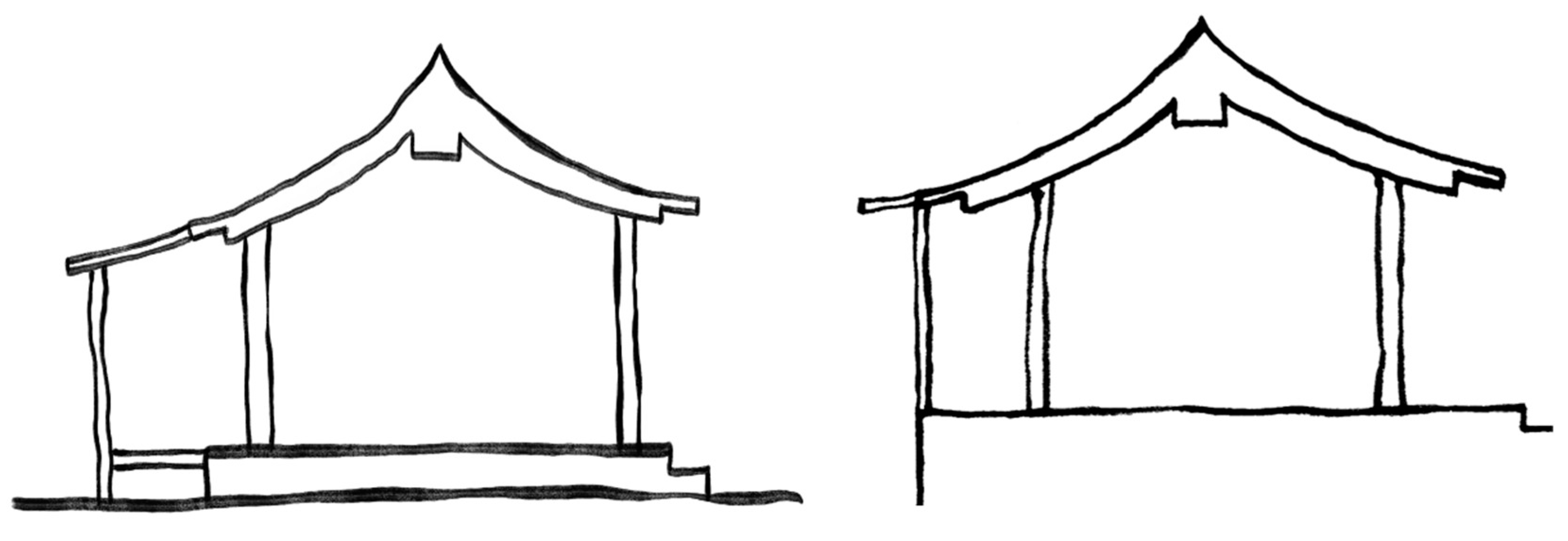

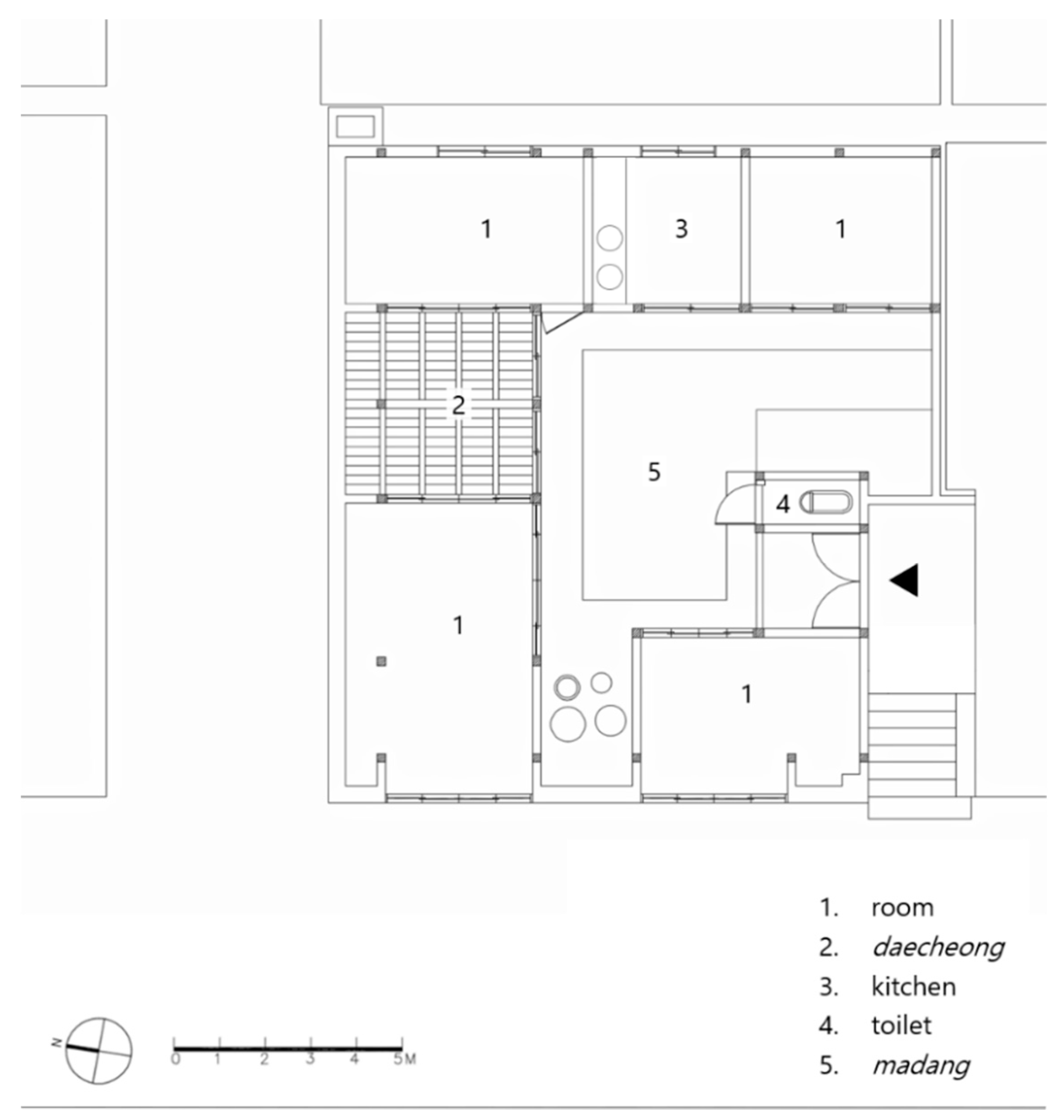

In Bukchon, the most representative

hanok village in Seoul, there is a unique

hanok, or traditional Korean house, which also looks modern (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). Originally built around 1940, the house underwent several stages of extension and repairs, and in 2000, was renovated by architect Wook Choi (born 1963) who called it “Samcheong Hanok” (or Samchung Hanok). Arguably, the evolution of the Samcheong Hanok illustrates a typical history of modern

hanok in the past century. In the history, sudden increases in the number of

hanok buildings were detected around two specific periods: first, approximately in the three decades from the early 1930s; second, in the past two decades from 2000. This phenomenon leads to classification of the

hanok as

urban-type or

contemporary, according to whether they were built in the first or second period, respectively [

1,

2].

Since the mid-1920s, housing demand increased rapidly due to urbanization and modernization in Seoul (housing shortage in Seoul soared from 5.5% in 1925 to 22.1% in 1936 and became most severe between 1935 and 1940; the housing development was most active during the latter period) [

3] (pp. 74–77) [

4] (pp. 25–26), but without an adequate construction system. Given the circumstances, the

hanok was the only type of house that could be swiftly constructed, and a modified version of the traditional

hanok was mass-produced for anonymous clients. This was the

urban-type hanok. However, further urbanization and modernization caused its decline from the 1960s, resulting from the dominance of Western-style houses and apartment buildings. New opportunities for the

hanok emerged around the late 1990s. At that time, the Seoul Metropolitan Government grappled with the preservation of old

hanok buildings in urban areas. A result of these efforts was the enactment of the “Hanok Registration System” stipulated in the “Plan of Bukchon Gardening” in 2001 (

Hanok owners in the Bukchon area, who are willing to preserve their

hanok buildings, can be financially supported in the improvement and repair works) [

5] (p. 9), which successfully drew attention to the

hanok from the public and the architectural profession. This induced a

hanok boom, providing architects with ample opportunities to initiate

hanok projects for specific clients, often with experimental designs breaking away from traditional standards. This newly modified

hanok—individualized and tailor-made, built during the revival—is referred to as the

contemporary hanok.

In this way, the two types of

hanok emerged in response to the demands of their respective times and represent the modern history of the

hanok. To investigate the history and evolution of the

hanok, this paper examines the Samcheong Hanok. There are several crucial reasons for focusing on this specific example. First, the Samcheong Hanok illustrates how both types of

hanok emerged and transformed over the past century. Though this house does not exhibit all the details that are representative of both

hanok types, it undoubtedly characterizes their major features. In particular, this house—as a

contemporary hanok—is the result of re-interpretation of tradition at the discretion of an individual architect. This fact forms a basis for discussion about a possible direction for

hanok in the future. Second, the Samcheong Hanok holds certain clues and records through which we can trace its history. Above all, numbers of previous studies on the

urban-type hanok of Bukchon provide historical data applicable to this house. More directly, various drawings (plans, sections, and elevations) and photographs, which show the pre- and post-renovation states of the house, are available (

Figure 3). (The author was provided with drawings and photographs by the architect. In fact, however, they had already been published—though some photographs differ—immediately following the completion of the renovation work [

6]). This availability is critical because the pre- and post-renovation floor plans and sections drawn by the architect allow us to understand the state of the house before and after the renovation. Third, the timing of renovation, that is, the year 2000, is significant as it was prior to the enactment of various

hanok support guidelines and regulations. For example, the “Seoul Hanok Support Ordinance” (2002) [

7] and the “Bukchon District Unit Plan (Type I)” (2010) [

8] were enacted following the aforementioned “Hanok Registration System” (2001) [

5]. Therefore, the house could ensure relatively free design processes for renovating the pre-existing

hanok, though it was not financially supported by the ordinance. The guidelines and regulations led to the

hanok boom but greatly limited fresh attempts at new

hanok designs. This Samcheong Hanok case would reveal an unintended effect of the

hanok support system.

Based on these reasons, this paper aims to trace and reconstruct a plausible history of the Samcheong Hanok, focusing on its floor plan. The (floor) plan is not only the “generator” of architecture—if following Le Corbusier (

Vers une Architecture, 1923) [

9]—but also the only common ground, on which different stages of the Samcheong Hanok evolution can be compared. This paper is expected to highlight typical aspects of modern

hanok while examining a possible direction for the

hanok in this new century.

2. Urban-Type Hanok and Contemporary Hanok

To discuss the Samcheong Hanok, we must review the

urban-type and

contemporary hanok, but a brief mention of the

hanok itself also seems necessary. The term “hanok”, literally “Korean house”, was coined at the turn of the twentieth century to distinguish traditional Korean buildings from Western-style ones, called “yangok”, that started being built around the time [

10]. Most of all, the

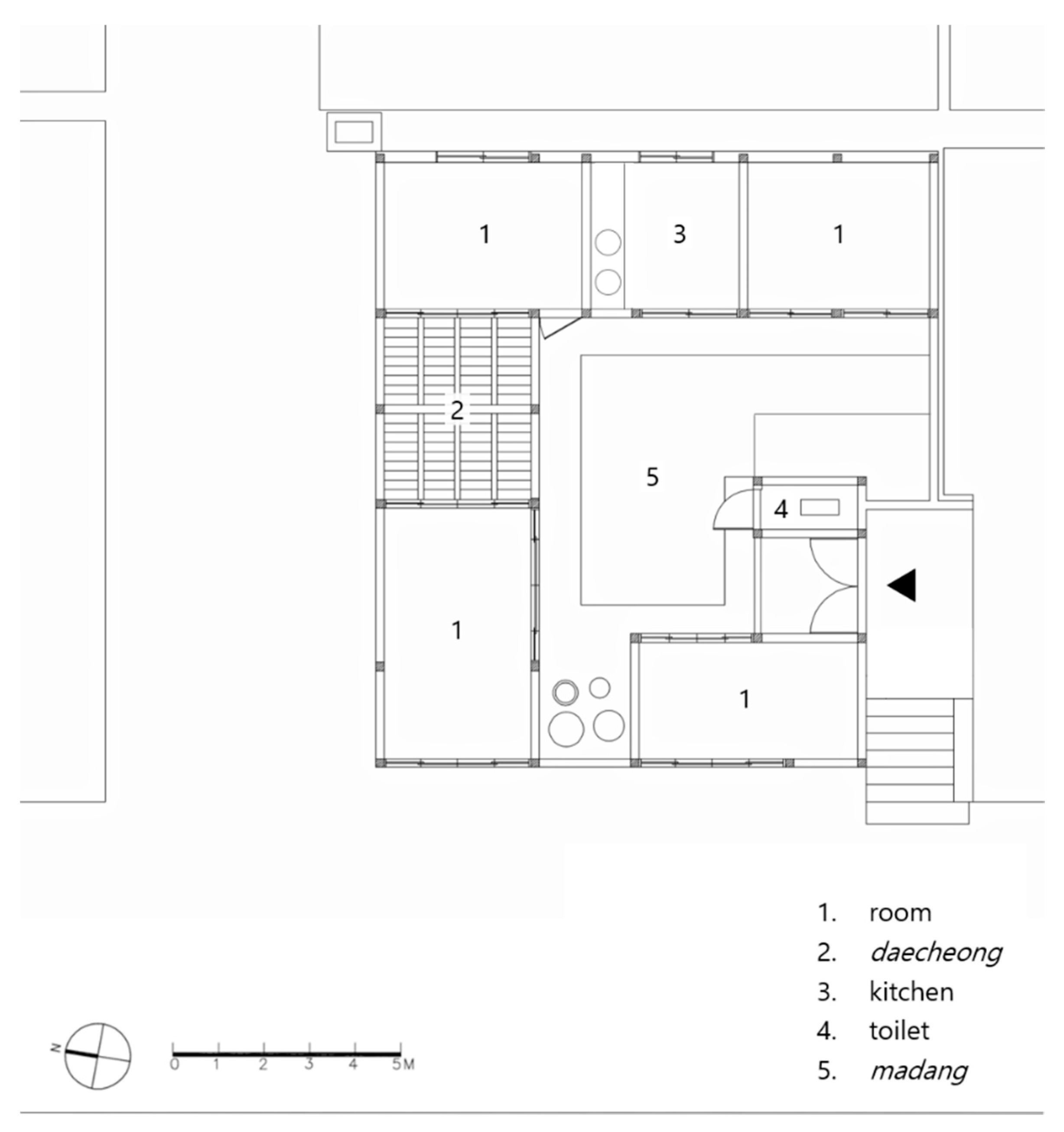

hanok is characterized by its wood-frame structure comprising columns, girders, beams, rafters, and many other smaller components (

Figure 4). This structure stands on a platform and supports its roof, whether tiled or thatched. In terms of space, the

hanok is unique, owing to the coexistence of the

ondol, or floor heated room, and the

maru, or wooden-floor space, within the same building. In general, several buildings together form one

hanok—particularly for upper class families—while outer walls define the boundary of the

hanok, within which the women’s quarter and the men’s quarter were further defined. The

madang, or courtyard, within the outer walls is also considered important because this outdoor space, though empty, can be flexibly used for various purposes. This traditional building type came to experience drastic changes in the twentieth century, with the emergence of the

urban-type hanok.

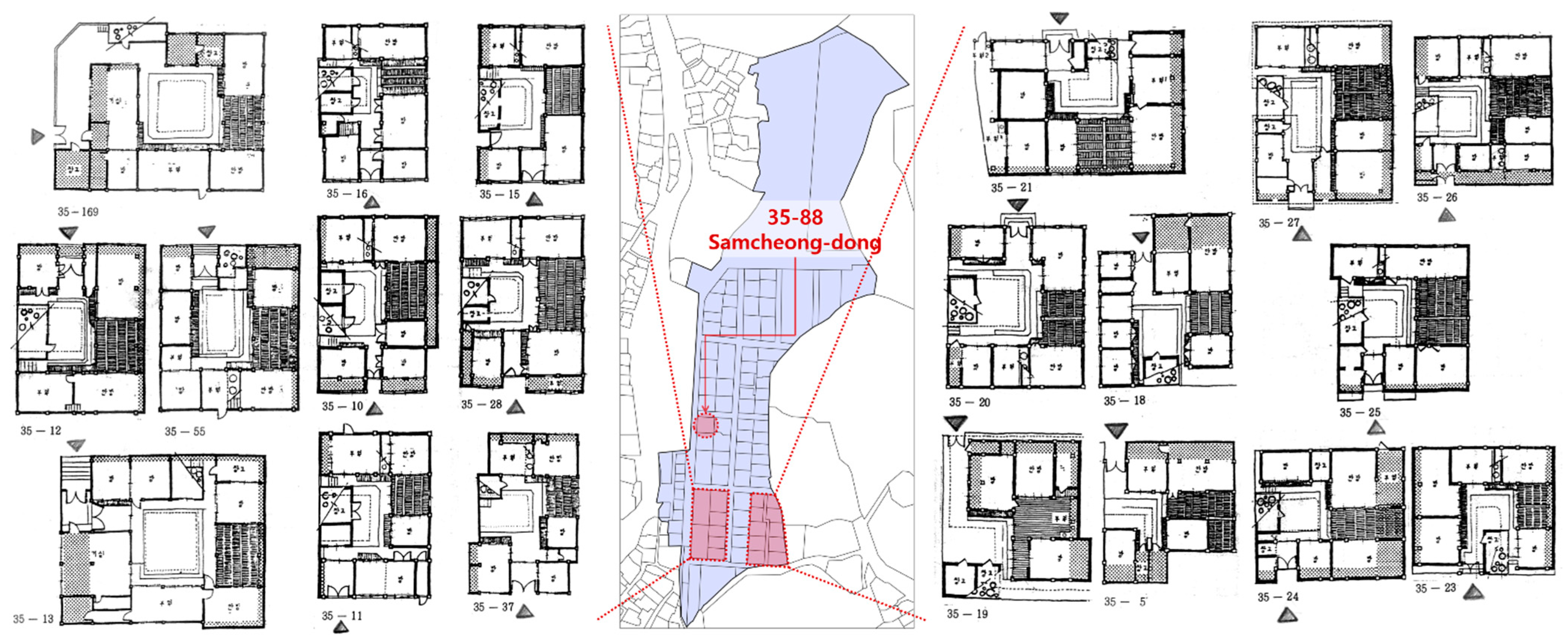

The

urban-type hanok, collectively built between 1930 and 1960, was the most universal housing type of the time that was newly adapted for the urbanization and modernization of Seoul (

Figure 5). Notably, rapid changes in urban planning at that time, including those pertaining to the street system and subdivision of housing lots, subsequently led to the modification of the traditional

hanok to a largely different

urban-type hanok. Based on studies, such as Song (1990), Seong (2003), and Jeon and Kwon (2012) [

1,

4,

10], the characteristics of the

urban-type hanok could be summarized as follows. First, the standardization of plan. This characteristic was definitely impacted by changes in the relationship between

hanok suppliers and clients (or consumers). With the emergence of specialized housing developers (or their organizations), the traditional “one-to-one” relationship between a carpenter and a client shifted to a new “one-to-many” relationship between one supplier and an unspecified number of clients [

1] (pp. 32–34). This mass-produced

hanok was commercialized while its plan was simplified, such as “ㄱ-shape,” “ㄷ-shape,” and “ㅁ-shape.” Second, the compactness of space. In the 1930s, many housing lots at the center of Seoul were subdivided—a larger lot was converted into a good number of smaller lots, thereby reducing the size of the required

hanok and compacting the spatial composition. As a result, for example, the

madang became centralized. Different to the typical

hanok in the past, which comprised several buildings and courtyards within outer walls, the

urban-type hanok basically contains a single courtyard at the center of the house (

Figure 6). At the same time, the building itself serves as the outer wall, which is unlike the traditional

hanok that has walls generally detached from main buildings. Another interesting change related to the compactness of space is the location of the toilet. It was previously detached from the main buildings but is now included in the

munganchae or gate building. Third, the neutralization of space. In the traditional

hanok, the space was divided into the women’s quarter,

anchae—the innermost building—and the men’s quarter,

sarangchae—the outer building, based on gender role. However, as the compact

urban-type hanok could not have such a spatial division, the space was neutralized. This characteristic signifies that the emergence of the

urban-type hanok not only influenced changes in the physical building but also in social consciousness. Fourth, the modernization of building equipment. Owing to the “Housing Improvement Movement” from the late 1920s [

11] (pp. 207–238), the old-fashioned lifestyle in the traditional

hanok was criticized and its modernization was promoted. This often related to building equipment in the toilet and kitchen, where watering, heating, and sanitation systems are integrated. Though not immediately implemented in early examples of the

urban-type hanok, the modernization of building equipment was gradually realized as technology advanced.

With the spread of modern housing (the

yangok single-family house, the apartment house, and the small or medium-scale multi-family house), however, the construction of the

urban-type hanok rapidly decreased from the late 1960s and remained confined to a limited area. In other words, existing

hanok buildings, whether traditional or

urban-type, have been destroyed by the modernization process—typically, the large-scale apartment development in urban and suburban areas; and the “Saemaeul Undong” (New Village Movement in Korea) of the 1970s and 1980s in the countryside. This crisis of

hanok in turn led to

hanok preservation movements: for example, various regulations for

hanok preservation have been introduced to Bukchon since 1970s [

5] (pp. 35–36). Yet, the

hanok faced another crisis from the beginning of the 1990s when residents in Bukchon demanded total easing of previous regulations for

hanok preservation to develop their properties according to their own specifications. Fortunately, various

hanok support guidelines and incentives introduced in the early 2000s, as aforementioned, actively helped the preservation and revival of the

hanok by successfully obtaining the cooperation of residents. In all, 353 out of the 912 houses in Bukchon were registered until November 2005 (registration rate of 38.7%), and 504 cases (313 cases of subsidy and 191 cases of loan) were determined eligible for remodeling support. As a result, 203

hanok buildings were remodeled with a total financial support of KRW 12.6 billion (KRW 9 billion as subsidy and KRW 3.6 billion as loan) [

13] (p. 29). With increased

hanok construction in Bukchon as a foothold, the

hanok has re-emerged in the world of architecture, partly sustained by the present trend of retro-styles. Combined with contemporary architecture, it is now called the

contemporary hanok. More precisely, the

contemporary hanok refers to a contemporary building that integrates modern constructional and/or finishing methods with the basic frame of

hanok, such as traditional wood structure, roof frame, and appearance [

2].

The

contemporary hanok has not yet been sufficiently studied; however, this paper defines its characteristics as follows. First, the modernization of building equipment and interior design. While maintaining the basic structure and form of the traditional

hanok, the

contemporary hanok adopts continually changing technologies to compensate for the shortcomings of an outdated

hanok as the

urban-type hanok did similarly. The poor cooling/heating system and hygienic equipment are most notable. In addition, it seeks contemporary stylistic preferences with sophisticated interior designs. Second, the use of updated building materials and construction methods. Attempts were made to graft contemporary structural components onto the traditional wood structure. Take the C Hanok (2013), renovated by Seung-mo Seo, for example, where parts of old wooden beams were replaced by steel beams, and wooden columns by a steel pipe and an H-shaped steel column. Moreover, the weight of the

hanok’s roof structure could be reduced by adopting a dry construction method, which uses dry roof tiles and eliminates the traditional layer of mud beneath the tiles—the wet-roof system of

hanok has been one of the most required parts to be modernized to improve the traditional

hanok. Further, architects sometimes break common-sense rules of the conventional

hanok structure, either to reduce construction costs or produce an aesthetic effect. Perhaps the most representative example is the Namsandong Hanok (2014) in Gyeongju, designed by the Japanese architect Masanori Tomii, in which the

daedeulbo, or crossbeam, was removed from the roof structure. This can be considered radical because the

daedeulbo is among the most critical and symbolic elements in traditional Korean architecture. Third, the vertical extension of space. One chief reason that the

hanok is not competitive in the present housing market is the low floor area ratio owing to its single-story structure. Recently, architects often insert basement and attic spaces—uncommon in the traditional

hanok—in their design to secure a maximum usable area of the building. Such a vertical extension of space, which suggests a possibility of a multiple-story

hanok, may be the most representative characteristic of the

contemporary hanok. Doo-jin Hwang, in particular, emphasizes the vertical extension of space as in Mumuheon (2004), Donginjae (2006), L Residence (2009), and Mokgyeongheon (2015) [

14]. Fourth, the combination with modern architecture. This refers to a unique situation wherein the composition of a single building is part

hanok and part modern; however, as a whole, the building could be regarded as a (

contemporary)

hanok. Although this characteristic is found only in a small number of cases, it is noteworthy. For instance, some

hanok buildings have a modern building part (or a Western-style wood structure); whereas some modern buildings have a

hanok part attached to their main structure. The Institute of Korean Royal Cuisine Building (2003) and Hamyangjae (2012), designed by Jung-goo Cho, and the DBEW Design Center (2003), designed by Seok-chul Kim, are the examples. Arguably, many

contemporary hanok buildings result from experimental attempts by creative architects who do not hesitate to combine the old with the new under current conditions.

4. Meaning of the Samcheong Hanok History

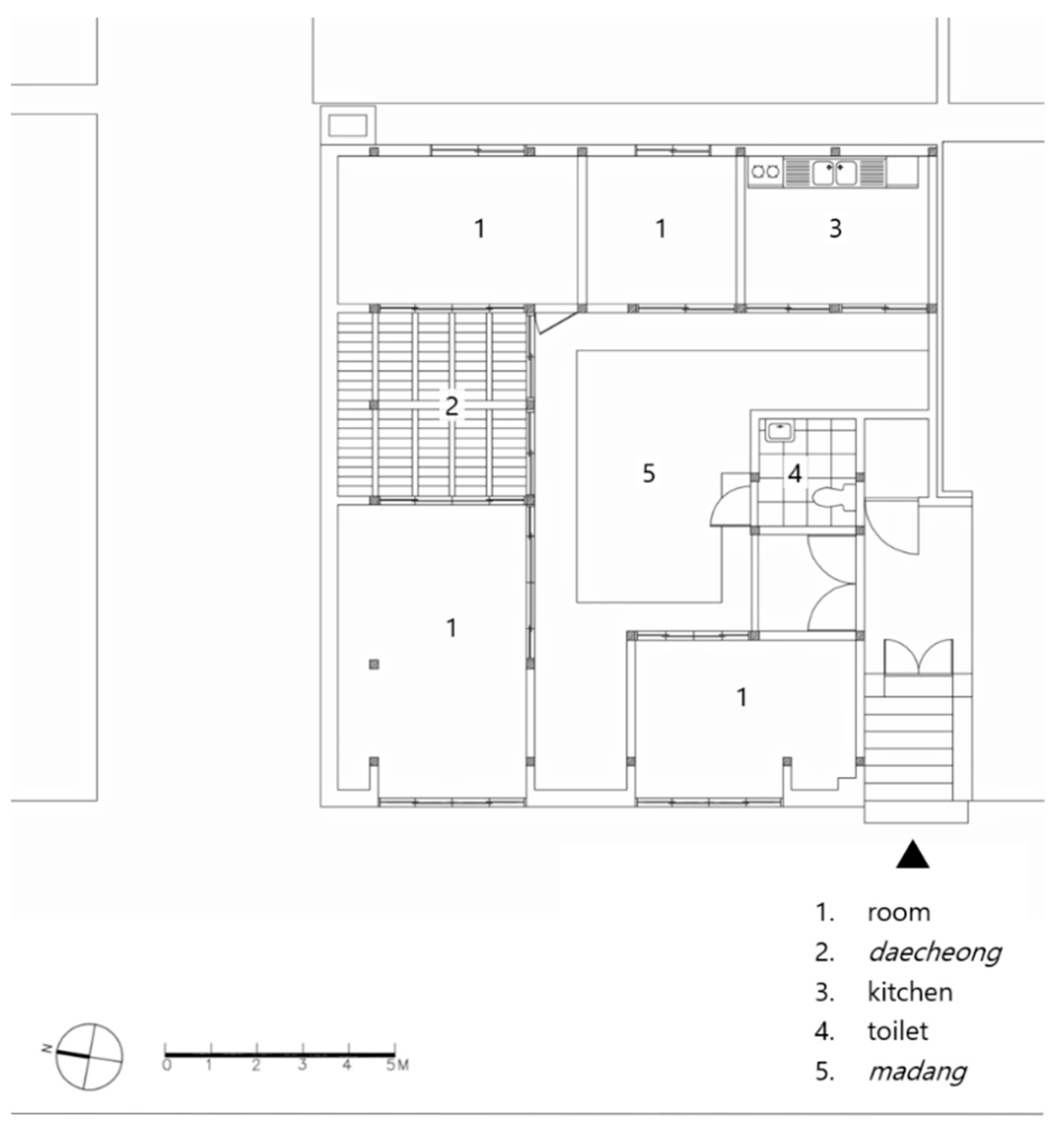

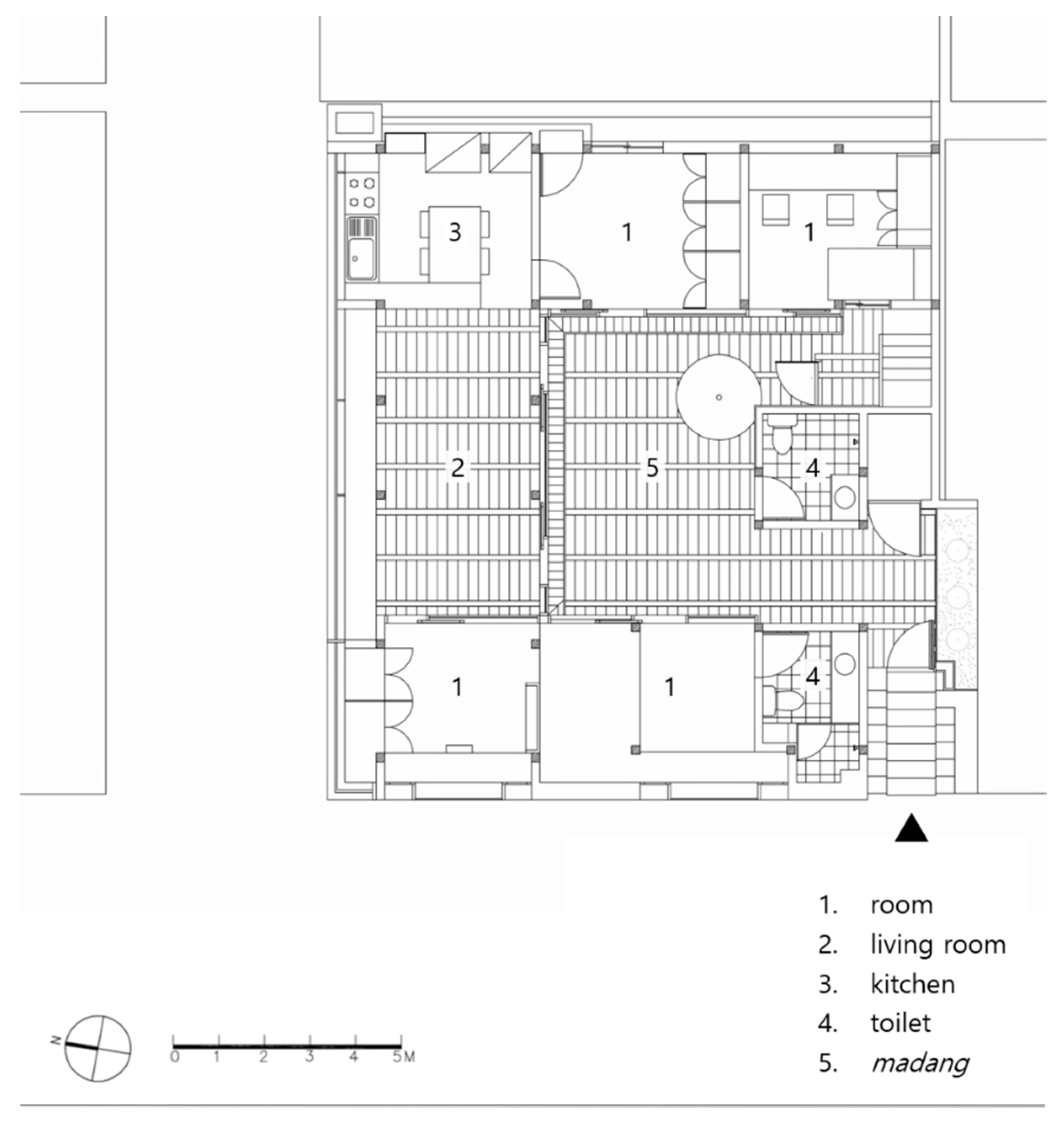

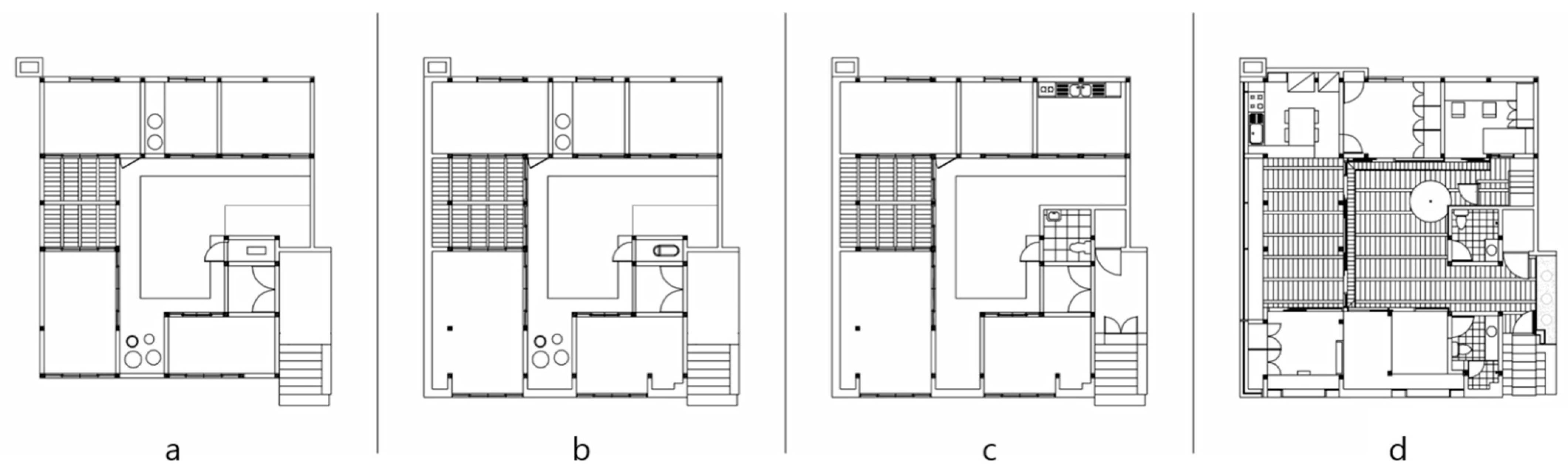

As discussed, there have been a series of changes in the Samcheong Hanok history, whether major or minor, ranging from the stage of new construction around 1940 to the stage of renovation in 2000, via the in-between stages of extension and repairs. Tracing the history, this study reconstructed the floor plans of the house in the first two stages, with relation to the architect’s floor plans in the last two stages. If we juxtapose and compare them (

Figure 18), we could more easily understand how the house has transformed through the stages over time. The extension of space is conspicuous in the second stage (early 1960s), and the modernization of kitchen and toilet in the third stage (1960s–1990s), although the most dramatic change is recognizable in the plan of the renovation stage (2000). If so, what does the history of the Samcheong Hanok tell us explicitly or implicitly?

4.1. Representing the History of Modern Hanok

What is explicit is the fact that the history of the Samcheong Hanok represents the history of modern

hanok. Summing up, the Samcheong Hanok was built on a sub-divided housing lot in Bukchon, Seoul around 1940 as one of the

urban-type hanok buildings, which were mass-produced approximately between 1930 and 1960. Accordingly, this house had all the characteristics of the

urban-type hanok as described in

Section 2. In particular, the standardization of plan and compactness of space were most obvious as typified in the “open ㅁ-shaped” plan with the courtyard

madang. Moving on to the early 1960s, the Samcheong Hanok extended to enlarge space just as the neighboring

urban-type hanok buildings were remodeled for extension. In the meanwhile, its building equipment and interior design must have been updated several times as seen in the pre-renovation plan. In this plan, the kitchen and the toilet were enlarged and refurbished, and this refurbishment matches the general trends in the

urban-type hanok of the time. Finally, the renovation in 2000 transformed the Samcheong Hanok from a modest

urban-type hanok into a unique

contemporary hanok. This stage can also be integrated into the history of the

urban-type hanok, although not all

urban-type hanok buildings experience such a radical transformation. Thus, the overall history of modern

hanok in the past century was manifested through the series of changes in this single building.

In addition, it is also explicit that the Samcheong Hanok, renovated in 2000, can be positioned at the starting point in the history of the

contemporary hanok. Of course, there have been many

hanok projects undertaken by reputed architects before the Samcheong Hanok was reborn at that time. For example, Neungsohun (1991) and Chungsongjae (1997), originally built in 1930s as typical

urban-type hanok buildings in Bukchon (Gye-dong), were renovated by Young-Sub Kim in 1990s [

20] (pp. 22–33). Though their renewal was notable, however, it is arguable that there was no fundamental infringement of tradition in these works. Likewise, most

hanok projects prior to 2000 rarely attempted to challenge or break (not just to mildly modify) the basic norm of the traditional

hanok in terms of the essential structure and form, even though they necessarily updated building equipment and interior design to accommodate modern life. Conversely, in the Samcheong Hanok, we can note diverse attempts to intentionally deviate from the traditional norm, whether they are the addition of modern cladding to the outer wall or the installation of the

maru-like wooden deck on the

madang. Therefore, discussions about the

contemporary hanok should begin with the Samcheong Hanok. Moreover, we need to notice the phenomenon of

hanok revival since 2000, along with the emergence of architects who reinterpret the traditional building type from a new perspective. If the “

hanok returned,” as one declared [

21], the Samcheong Hanok was undoubtedly in the lead.

4.2. Irony in the Hanok Support System

On the other hand, this study claims that the Samcheong Hanok history, specifically the timing of its rebirth as the contemporary hanok, signifies something implicitly. That is a certain irony in the hanok support system or the set of all the guidelines and regulations for promoting hanok buildings. In other words, the Samcheong Hanok reveals the paradox that various guidelines and regulations introduced to promote hanok buildings failed to serve as the system for the evolution of the hanok. We may regard that the hanok support system was initiated from the “Hanok Registration System” and “Plan of Bukchon Gardening” in 2001, a year after the renovation project of the Samcheong Hanok. (Though there had already been various regulations for hanok preservation in Bukchon, the hanok regulations from the early 2000 became more supportive to residents or owners of hanok in terms of administration and finance while they became as much restrictive as supportive.) Subsequently, it has led to the “Seoul Hanok Support Ordinance” and the “Jeonju Hanok Support Ordinance” in 2002, the “Bukchon District Unit Plan (Type I)” in 2010, and the “Act on Value Enhancement of Hanok and Other Architectural Assets” in 2015. (Besides these, many local governments have their own hanok ordinances, which are now supported by the “Act on Value Enhancement of Hanok and Other Architectural Assets”). We can understand here that the initial set of guidelines to preserve the hanok buildings in a local area had gradually developed and was finally legislated as a national law to support their preservation and new construction in terms of finance and administration. However, various conditions in the guidelines and legal clauses sometimes act as excessive restrictions. In particular, the “Bukchon District Unit Plan (Type I): Enforcement Guidelines” includes excessive and detailed regulations concerning the formal aspects of the hanok—for example, the finishing materials of exterior, the patterns of windows/doors, and various types of decorations, as well as the length of the eaves and the allowable examples of roof-tiles (Sections 1 and 4, Article 26; Sections 1, 2 and 4, Article 28). Due to these restrictions, architects’ discretion over hanok design in Bukchon became extremely limited, and similar restrictions were observed in the local governments’ hanok ordinances and the national law “Act on Value Enhancement of Hanok and Other Architectural Assets”.

From this perspective, it was fortunate that renovation of the Samcheong Hanok was conducted prior to the restrictive guidelines, especially those in the “Bukchon District Unit Plan (Type I)”. For this reason, Wook Choi was able to make radical and challenging attempts in the project, paving the way for evolution of the hanok. Perhaps the renovated Samcheong Hanok has many design elements that would have still been possible even if those hanok guidelines and regulations had been introduced before 2000. However, most experimental attempts described in the previous section seemed to be hardly feasible under the currently established hanok support system. For example, it might have been impossible for the outer wall of the house to be clad in the unique timber-screen because the elevations of hanok that face streets shall adequately express the composition of the wooden structure according to the guidelines in “Bukchon District Unit Plan (Type I)” (Section 1, Article 28). It is likely that more drastic actions, such as the removal of the tiles (if considered “glossy”) that were attached to the outer wall before the renovation, may have been taken to emphasize its traditional appearance if the guidelines had been provided (Sections 3 and 6, Article 28)—not to mention the apparent disapproval of the installation of the unfamiliar cladding in the wall. Moreover, it might have been impossible to install non-traditional style windows in the western wall and the northern wall because the guidelines only allow traditional window patterns—for example, the ddichangsal, yongjachang, wanjachang, jeongjachang, and sutdaesal (Section 4, Article 28). Last but not least, the wooden deck in the madang must have been controversial because the guidelines regulate the attachment of structures to the madang: “any structure to be built in the madang is recommended to keep a certain distance from the hanok in an appropriate manner” (Section 1, Article 34). Though not an enforced, but recommended, regulation, different from the other regulations mentioned so far, this would have suppressed the novel idea and prevented the architect from further experimenting with the design.

Bukchon is a very special area where numerous

hanok buildings exist, and therefore, a sort of traditional scenery must be retained. Nevertheless, this paper maintains that the Bukchon guidelines, and eventually, all the

hanok-related regulations in Korea, are too rigid and thus prevent the evolution of

hanok. From this perspective, Doo-jin Hwang’s assertion—at “The 1st AURI (Architecture & Urban Research Institute) Discussion about the ‘Hanok Architectural Style,’” held in Seoul on 22 November 2019—that Bukchon is “a graveyard of

hanok creativity” is understandable. Though various experimental

hanok projects have been undertaken for the last two decades—in legal interstices where the regulations fail to cover—as discussed in

Section 2, it can be argued that a creative evolution of

hanok is being considerably prevented by the present regulations. The

hanok is not only a heritage from the past, but it should also represent current and future architecture. Therefore, we must have a more flexible concept of the present and future

hanok design. In this way, the timing of the Samcheong Hanok renovation awakens the irony implied in the

hanok support system.

5. Conclusion: Towards a Creative Evolution of Hanok

This study demonstrated that the Samcheong Hanok is a meaningful case in the history of modern

hanok from the early 20th century onwards. In conclusion, we can note several points for a creative evolution of

hanok from this study. First, active responses to the demands of time are always significant. The

urban-type hanok and the

contemporary hanok are the results of the responses observed in the Samcheong Hanok history. Likewise, to actively respond to the demands of time, it is necessary for continual evolution of the

hanok towards the future. Second, the renovation of pre-existing

hanok buildings plays an effective role in leveraging the evolution of

hanok. In contrast to the new construction of the traditional-type buildings, of which revival is often controversial [

14], the renovation of old

hanok buildings is required to adapt them to contemporary lifestyle and reuse the existing resources. Thus, the renovation implies the natural encounter between the old and the new, and their heterogeneous conjunction, often with experimental designs, stimulates the evolution of

hanok. Arguably, one possible way of its creative evolution was hinted at in the renovation work of the Samcheong Hanok. Third, it is creative architects that generate the most important momentum for the evolution of

hanok. If renovation of the Samcheong Hanok hinted at one way of

hanok evolution, its main promoter was undoubtedly the architect as a creative designer. We must highly regard the challenging attitudes of architects who do not hesitate to trigger changes in convention even though the role of anonymous players, such as builders and clients, should also not be ignored. Fourth, a creative evolution of the

hanok support system is required for the creative evolution of

hanok itself. As argued in the previous section, the current

hanok support system often limits creative designs of the

hanok. A more flexible system for the future of the

hanok is needed. While the

hanok support system has focused on the preservation of traditional aspects of the

hanok from a conservative perspective, it is time to evaluate the diversity and modernity of the

hanok for its creative evolution.