(Non)Environmental Alternative Action Organizations under the Impacts of the Global Financial Crisis: A Comparative European Perspective

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review: Solidarity and Environmental Activism during Hard Times

3. Materials and Methods

- basic and urgent needs (related to food, shelter, medical services, clothing, free legal advice and anti-eviction initiatives),

- economy (involving alternative coins, barter clubs, financial support, products and service provision on low prices, fundraising activities, second-hand shops and bazaars),

- energy and environment (protection of the environment or wild life, focus on renewable energy, climate change, anti-carbon, anti-nuclear power, waste management, recycling or animal rights),

- alternative consumption such as producer-consumer actions, community gardens, boycotts and buycotts

- interest group advocacy,

- self-organized spaces,

- culture and education,

- civic media,

- actions for preventing hate crime or

- to stop human trafficking [65].

Defining Environmental AAOs

4. Results and Discussion

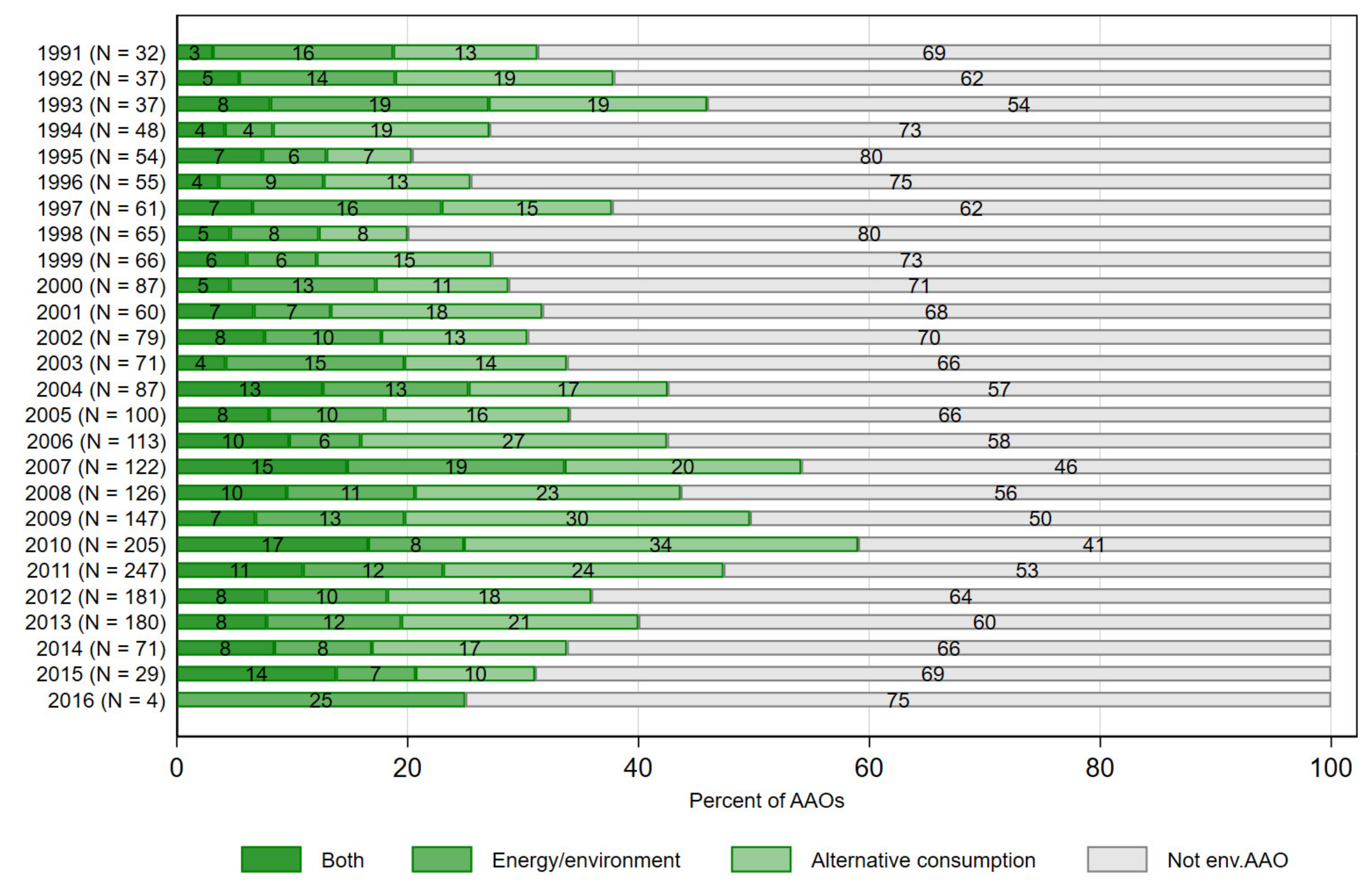

4.1. Who Are the AAOs and to What Extent Are They Environment Oriented?

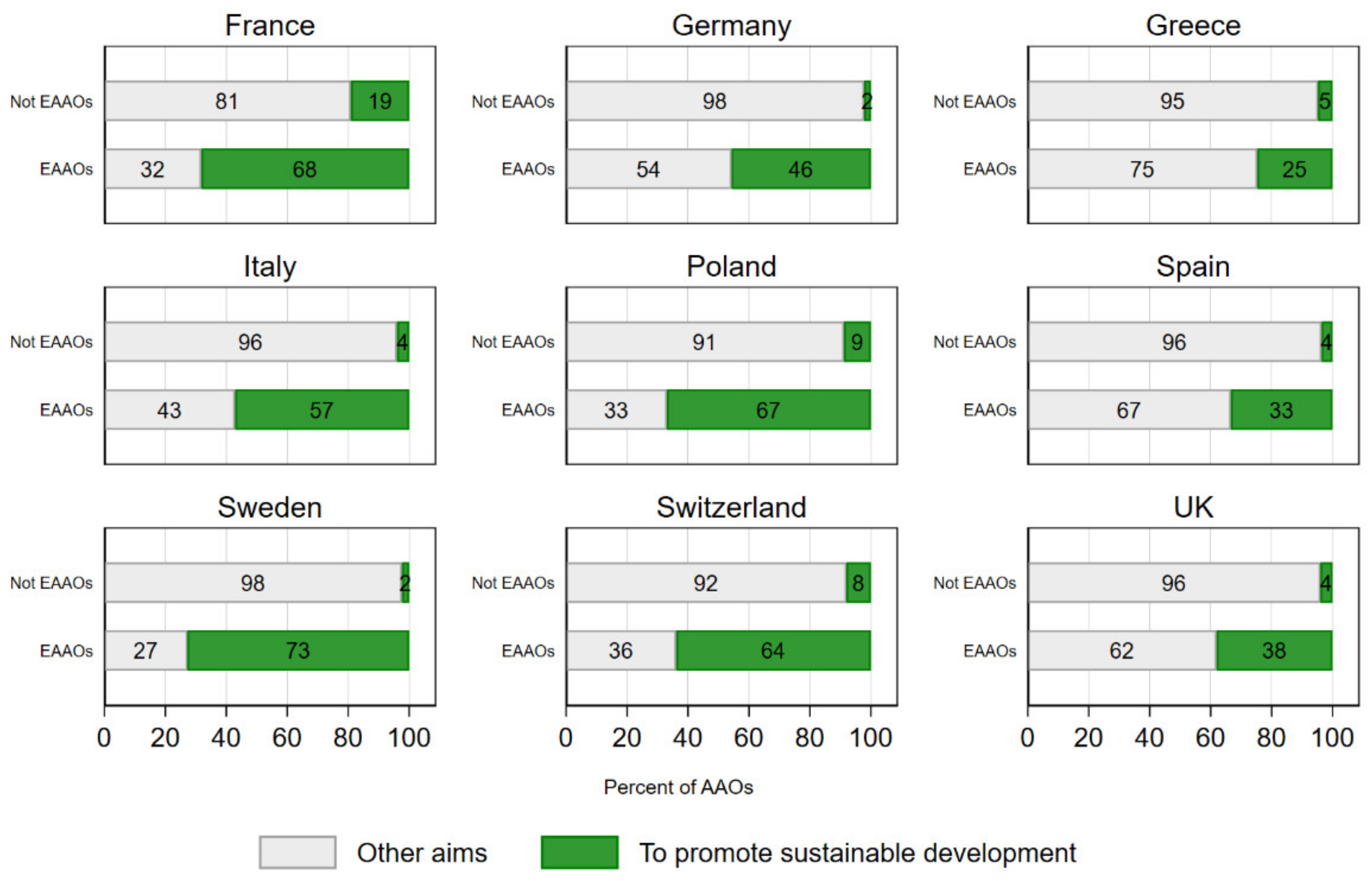

4.2. Which Aims Drive (Non)Environmental AAOs to Mitigate the Risks of the Economic Crisis?

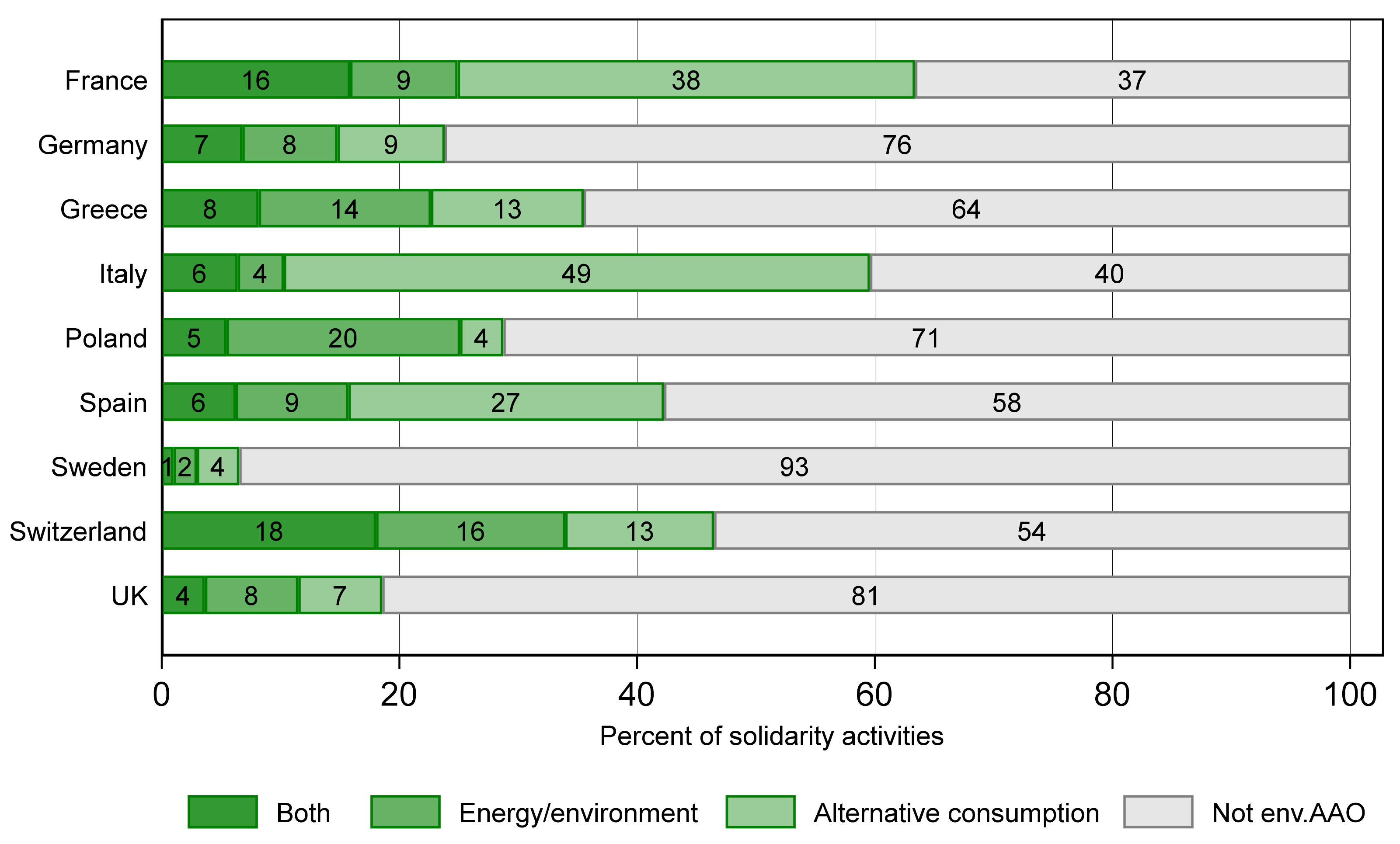

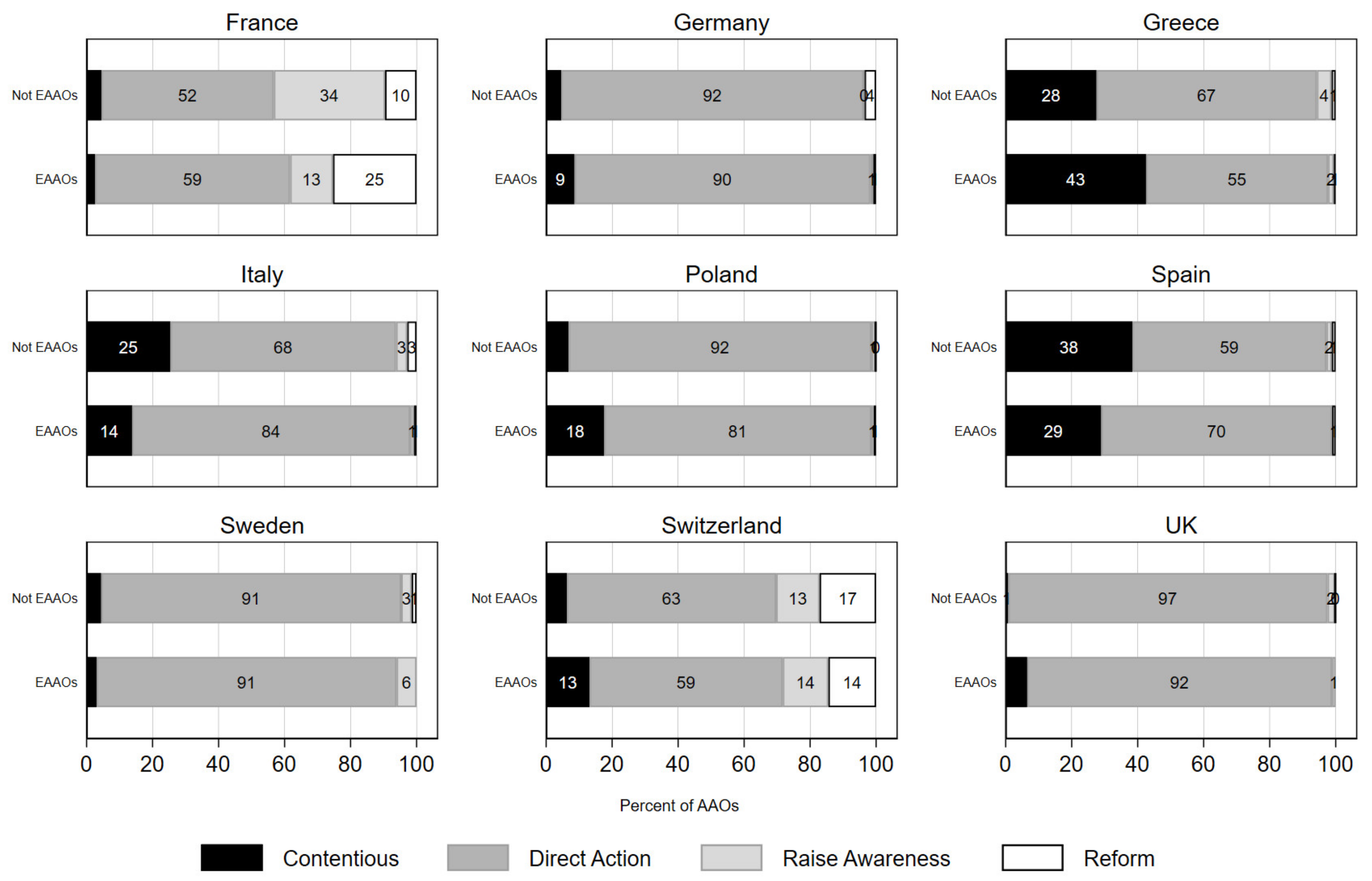

4.3. Through Which Strategies and Actions Do (Non)Environmental AAOs Manage Vulnerabilities during the Economic Crisis?

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Falkner, G. The EU’s current crisis and its policy effects: Research design and comparative findings. J. Eur. Integr. 2016, 38, 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Petropoulos, N.; Tsobanoglou, G.O. The Debt Crisis in the Eurozone: Social Impacts; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Ohlendorf, N.; Görlach, B.; Umpfenbach, K.; Mehling, M. Economic Stimulus in Europe–Accelerating Progress towards Sustainable Development? Background Paper; Ecologic Institute: Berlin, Germany, 2009; Available online: https://www.sd-network.eu/pdf/conferences/2009_prague/ESDN_Recovery_Report_020709_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2021).

- Klein, C. The environmental deficit: Applying lessons from the economic recession. Ariz. Law Rev. 2009, 51, 651–684. [Google Scholar]

- Lekakis, J.N.; Kousis, M. Economic crisis, Troika and the environment in Greece. South Eur. Soc. Politics 2013, 18, 305–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tienhaara, K. A tale of two crises: What the global financial crisis means for the global environmental crisis. Environ. Policy Gov. 2010, 20, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratter, B.M.; Philipp, K.H.; von Storch, H. Between hype and decline: Recent trends in public perception of climate change. Environ. Sci. Policy 2012, 18, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van-der Heijden, A. The Dutch 2010 elections and the environment. Environ. Politics 2010, 19, 1000–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotta, B.; Memoli, V. Do environmental preferences in wealthy nations persist in times of crisis? The European environmental attitudes (2008–2017). Riv. Ital. Sci. Politica 2019, 50, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, D.R. The broader importance of #FridaysForFuture. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2019, 9, 430–431. [Google Scholar]

- de Moor, J.; De Vydt, M.; Uba, K.; Wahlström, M. New kids on the block: Taking stock of the recent cycle of climate activism. Soc. Mov. Stud. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhan, S. The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pan-Syndemic—Will We Ever Learn? Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grasso, M.; Giugni, M. Introduction: Environmental Movements Worldwide. In The Routledge Handbook of Environmental Movements; Grasso, M., Giugni, M., Eds.; Routledge; forthcoming.

- Martinez-Alier, J.; Temper, L.; Del Bene, D.; Scheidel, A. Is there a global environmental justice movement? J. Peasant Stud. 2016, 43, 731–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forno, F.; Graziano, P.R. Sustainable community movement organizations. J. Consum. Cult. 2014, 14, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smith, A.; Fressoli, M.; Abrol, D.; Arond, E.; Ely, A. Grassroots Innovation Movements; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kousis, M.; Paschou, M. Alternative Forms of Resilience: A Typology of approaches for the study of Citizen Collective Responses in Hard Economic Times. Partecip. E Confl. 2017, 10, 136–168. [Google Scholar]

- Kousis, M.; Paschou, M.; Loukakis, A. Transnational Solidarity Organizations and their main features, before and since 2008: Adaptive and/or Autonomous? Sociol. Res. Online. forthcoming.

- Bosi, L.; Zamponi, L. Direct Social Actions and Economic Crises: The Relationship between Forms of Action and Socio-Economic Context in Italy. Partecip. E Confl. 2015, 8, 367–391. [Google Scholar]

- Bosi, L.; Zamponi, L. Paths toward the same form of collective action: Direct social action in times of crisis in Italy. Soc. Forces 2020, 99, 847–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Moor, J.; Catney, P.; Doherty, B. What hampers ‘political’ action in environmental alternative action organizations? Exploring the scope for strategic agency under post-political conditions. Soc. Mov. Stud. 2021, 20, 312–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chatterton, P.; Pickerill, J. Everyday activism and transitions towards post-capitalist worlds. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2010, 35, 475–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, K. Becoming Citizen Green: Prefigurative politics, autonomous geographies, and hoping against hope. Environ. Politics 2014, 23, 140–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolopoulou, E. Neoliberalism and social-environmental movements in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crash: Linking struggles against social, spatial and environmental Inequality. In The Routledge Handbook of Environmental Movements; Grasso, M., Giugni, M., Eds.; Routledge; forthcoming.

- Alvaredo, F.; Chancel, L.; Piketty, T.; Saez, E.; Zucman, G. World Inequality Report 2018; Belknap Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kousis, M. Theoretical Perspectives on European Environmental Movements. In Social Movement Studies in Europe: The State of the Art; Fillieule, O., Accornero, G., Eds.; Berghahn Books: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Volume 16, p. 133. [Google Scholar]

- Caniglia, B.S.; Brulle, R.J.; Szasz, A. Civil society, social movements, and climate change. Clim. Chang. Soc. Sociol. Perspect. 2015, 1, 235–268. [Google Scholar]

- Pellow, D.N. Environmental justice movements and social movement theory. In The Routledge Handbook of Environmental Justice; Holifield, R., Chakraborty, J., Walker, G., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Curnow, J.; Helferty, A. Contradictions of Solidarity: Whiteness, Settler Coloniality, and the Mainstream Environmental Movement. Environ. Soc. 2018, 9, 145–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kousis, M.; Giugni, M.; Lahusen, C. Action organization analysis: Extending protest event analysis using hubs-retrieved websites. Am. Behav. Sci. 2018, 62, 739–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriesi, H.; Koopmans, R.; Duyvendak, J.W.; Giugni, M. New Social Movements in Western Europe: A Comparative Analysis; Universiy of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1995; Volume 8. [Google Scholar]

- Jamison, A. The Making of Green Knowledge: Environmental Politics and Cultural Transformation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Schlosberg, D.; Coles, R. The new environmentalism of everyday life: Sustainability, material flows and movements. Contemp. Political Theory 2016, 15, 160–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tilly, C. Social Movements as Historically Specific Clusters of Political Performances. Berkeley J. Sociol. 1994, 38, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Rootes, C.; Brulle, R. Environmental movements. In The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social and Political Movements; Snow, D., della Porta, D., Klandermans, B., McAdam, D., Eds.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Eder, K. A theory of collective identity making sense of the debate on a ‘European identity’. Eur. J. Soc. Theory 2009, 12, 427–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rootes, C. Environmental Movements: Local, National and Global; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Freudenberg, N.; Steinsapir, C. Not in our backyards: The grassroots environmental movement. Soc. Nat. Resour. 1991, 4, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kousis, M. Sustaining Local Environmental Mobilisations: Groups, Actions and Frames in Southern Europe. Environ. Politics 1999, 8, 172–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giugni, M.; Grasso, M.T. Environmental movements in advanced industrial democracies: Heterogeneity, transformation, and institutionalization. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2015, 40, 337–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Avenell, S. From fearsome pollution to Fukushima: Environmental activism and the nuclear blind spot in contemporary Japan. Environ. Hist. 2012, 17, 244–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreiling, M.C.; Lougee, N.; Nakamura, T. After the meltdown: Explaining the silence of Japanese environmental organizations on the Fukushima nuclear crisis. Soc. Probl. 2017, 64, 86–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulaert, F. The International Handbook on Social Innovation: Collective Action, Social Learning and Transdisciplinary Research; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Moulaert, F.; Ailenei, O. Social Economy, Third Sector and Solidarity Relations: A Conceptual Synthesis from History to Present. Urban. Stud. 2005, 42, 2037–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekakis, E.J.; Forno, F. Political Consumerism in Southern Europe. In The Oxford Handbook of Political Consumerism; Boström, M., Micheletti, M., Oosterveer, P., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Castells, M.; Caraca, J.; Cardoso., G. Aftermath: The Cultures of Economic Crisis; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- D’Alisa, G.; Demaria, F.; Kallis, G. Degrowth: A Vocabulary for A New Era; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cloke, P.; May, J.; Williams, A. The geographies of food banks in the meantime. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2017, 41, 703–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shantz, J. Anarchy in Action: Especifismo and Working-Class Organizing. In Beyond Capitalism: Building Democratic Alternatives for Today and The Future; Shantz, J., Macdonald, J.B., Eds.; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Blühdorn, I. Post-capitalism, post-growth, post-consumerism? Eco-political hopes beyond sustainability. Glob. Discourse 2017, 7, 42–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Asara, V.; Profumi, E.; Kallis, G. The Indignados as a socioenvironmental movement. Framing the crisis and democracy. Environ. Policy Gov. 2016, 26, 527–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kalogeraki, S.; Papadaki, M.; Pera Ros, M. Exploring the social and solidarity economy sector in Greece, Spain, and Switzerland in Times of Crisis. Am. Behav. Sci. 2018, 62, 856–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristancho, C.; Loukakis, A. A comparative regional perspective on alternative action organization responses to the economic crisis across Europe. Am. Behav. Sci. 2018, 62, 758–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahn, D. New internal politics in western democracies: The impact of the environmental movement in highly industrialized democracies. In Parties, Governments and Elites; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2017; pp. 125–150. [Google Scholar]

- Szulecka, J.; Szulecki, K. Polish Environmental Movement 1980–2017: (De) Legitimization, Politics & Ecological Crises. ESPRi Working Paper No. 6; 19 November 2017. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3075126 (accessed on 10 August 2021).

- Kousis, M.; Eder, K. EU policy-making, local action, and the emergence of institutions of collective action. In Environmental Politics in Southern Europe; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2001; pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Uba, K.; Kousis, M. Constituency groups of alternative action organizations during hard times: A comparison at the solidarity orientation and country levels. Am. Behav. Sci. 2018, 62, 816–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzini, J. Political Consumerism and Food Activism. In The Routledge Handbook of Environmental Movements; Grasso, M., Giugni, M., Eds.; Routledge; forthcoming.

- Wickes, R.; Zahnow, R.; Mazerolle, L. Community Resilience Research: Current approaches, challenges and opportunities, conference paper. In Proceedings of the Recent advances in national security technology and research: Proceedings of the 2010 National Security Science and Innovation Conference, Canberra, Australia, 23 September 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, K.; Zautra, A. Community resilience: Fostering recovery, sustainability, and growth. In The Social Ecology of Resilience: A Handbook of Theory and Practice; Ungar, M., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Berkes, F.; Ross, H. Community Resilience: Toward an Integrated Approach. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2013, 26, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loukakis, A.; Kiess, J.; Kousis, M.; Lahusen, C. Born to Die Online? A Cross-National Analysis of the Rise and Decline of Alternative Action Organizations in Europe. Am. Behav. Sci. 2018, 62, 837–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kousis, M.; Loukakis, A.; Paschou, M.; Lahusen, C. Waves of transnational solidarity organizations in times of crises: Actions, obstacles and opportunities in Europe. In Citizens’ Solidarity in Europe; Lahusen, C., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, G.G.E.; Kousis, M.; Lahusen, C. Measuring organisational practices of solidarity across sectors and countries. SAGE Res. Methods Doing Res. Online. forthcoming.

- LIVEWHAT WP6 Codebook. 2016. Available online: https://www.unige.ch/livewhat/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Deliverable-6.1.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2021).

| Type | Env. AAOs (%) | Non-EAAOs (%) |

|---|---|---|

| NGOs | 41 | 31 |

| Informal and/or protest gr. | 28 | 14 |

| Informal platform | 2 | 3 |

| Social economy | 21 | 16 |

| Charities, church | 5 | 20 |

| Trade unions | 0.4 | 0.45 |

| Other | 11 | 5 |

| All | 100% (1461) | 100% (2696) |

| Type of Solidarity | Env. AAOs (%) | Non-EAAOs (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Mobilizing for mutual help | 69 | 39 |

| Support between groups | 29 | 17 |

| Offer support to others | 26 | 49 |

| Distribution goods/services | 33 | 55 |

| Total N (percentages go over 100%, as multiple selection was allowed in the pre-defined list) | 1461 | 2696 |

| Constituency Groups (Not Mutually Exclusive) | Env. AAOs (%) | Non-EAAOs (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Animals | 3 | 0.01 |

| Children/teens/young/students | 19 | 25 |

| Consumers | 23 | 3 |

| Disabled/elderly | 2 | 9 |

| General population | 13 | 13 |

| Local community | 9 | 4 |

| Poor | 6 | 9 |

| Small enterprise | 16 | 4 |

| Refugees/migrants | 3 | 6 |

| Total number of AAOs (does not add to 100% given dichotomous variables, multiple answers allowed) | 1461 | 2696 |

| Aims (Not Mutually Exclusive) | Env. AAOs (%) | Non-EAAOs (%) |

|---|---|---|

| To reduce the negative impacts of the economic crisis/austerity | 9 | 12 |

| To reduce poverty and exclusion | 16 | 35 |

| To combat discrimination/promote equality of participation | 12 | 29 |

| To increase tolerance & mutual understanding | 7 | 18 |

| To promote alternative economic practices, lifestyles | 63 | 15 |

| To promote and achieve social change | 31 | 31 |

| To promote and achieve individual change | 17 | 37 |

| To promote sustainable development | 53 | 5 |

| To promote health, education, welfare | 15 | 34 |

| To promote alternative noneconomic practices, lifestyles and values | 22 | 12 |

| To promote democratic practices | 18 | 21 |

| To promote social movement actions and collective identities | 10 | 9 |

| Total N (percentages go over 100%, as multiple selection was allowed in the pre-defined list of aims) | 1461 | 2696 |

| Type of Strategies | Env. AAOs (%) | Non-EAAOs (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Contentious (protests) | 16 | 12 |

| Direct Action | 72 | 80 |

| Raise awareness | 5 | 5 |

| Reform | 7 | 3 |

| Total | 100% (1461) | 100% (2696) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kousis, M.; Uba, K. (Non)Environmental Alternative Action Organizations under the Impacts of the Global Financial Crisis: A Comparative European Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8989. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168989

Kousis M, Uba K. (Non)Environmental Alternative Action Organizations under the Impacts of the Global Financial Crisis: A Comparative European Perspective. Sustainability. 2021; 13(16):8989. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168989

Chicago/Turabian StyleKousis, Maria, and Katrin Uba. 2021. "(Non)Environmental Alternative Action Organizations under the Impacts of the Global Financial Crisis: A Comparative European Perspective" Sustainability 13, no. 16: 8989. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168989

APA StyleKousis, M., & Uba, K. (2021). (Non)Environmental Alternative Action Organizations under the Impacts of the Global Financial Crisis: A Comparative European Perspective. Sustainability, 13(16), 8989. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168989