Selected Determinants of Stakeholder Influence on Project Management in Non-Profit Organizations

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What is the level of project maturity in the area of managing stakeholder engagement in non-profit organizations in Poland?

- What factors influence the level of project maturity in the area of managing stakeholder engagement in non-profit organizations in Poland?

2. The Concept of Project Stakeholders in Non-Profit Organizations

- Stage 1 (stakeholder identification) consists of identifying all stakeholders who can potentially create the project environment. Most often, tables with a list of stakeholders or stakeholder maps are created, which graphically present the project environment, broken down into appropriate categories.

- Stage 2 (analysis and evaluation) covers the definition of key stakeholder characteristics, such as strengths and weaknesses, expectations towards the project, possibilities of articulating and enforcing one’s interests. Stakeholders are prioritized on this basis. It is advisable to review the analyzes of completed projects so as not to repeat the same mistakes.

- Stage 3 (preparation of engagement plans) is the preparation of an action plan for each stakeholder identified as significant during the analysis and evaluation phase. This plan aims to fully involve them in the project, which will increase the chance of the success of the project. In general, several stakeholder engagement strategies are included. The most important of these are: blocking, informing, inclusion in the project, consulting, ignoring and monitoring.

- Stage 4 (organizing the engagement process) consists primarily of assessing the team’s potential and determining the feasibility of the plan. On this basis, a decision can be made to increase the specific competences of team members and prepare resources for task implementation in relation to stakeholders.

- Stage 5 (stakeholder engagement) covers all commercially viable activities that are necessary to elicit and maintain specific stakeholder attitudes and behaviors towards the project. The main tool for stakeholder engagement is the communication plan. During the project implementation, project experience should be gathered on an ongoing basis.

- Stage 6 (evaluation and continual improvement) takes place after the end of the project. Then, one should gather project experience and evaluate the stakeholder engagement process. The conclusions of the evaluation should be used to improve the process as a whole and its individual elements. The accuracy of the stakeholder analysis, the effectiveness of the strategies used in relation to individual groups and the level of contractors’ competences should be particularly carefully assessed.

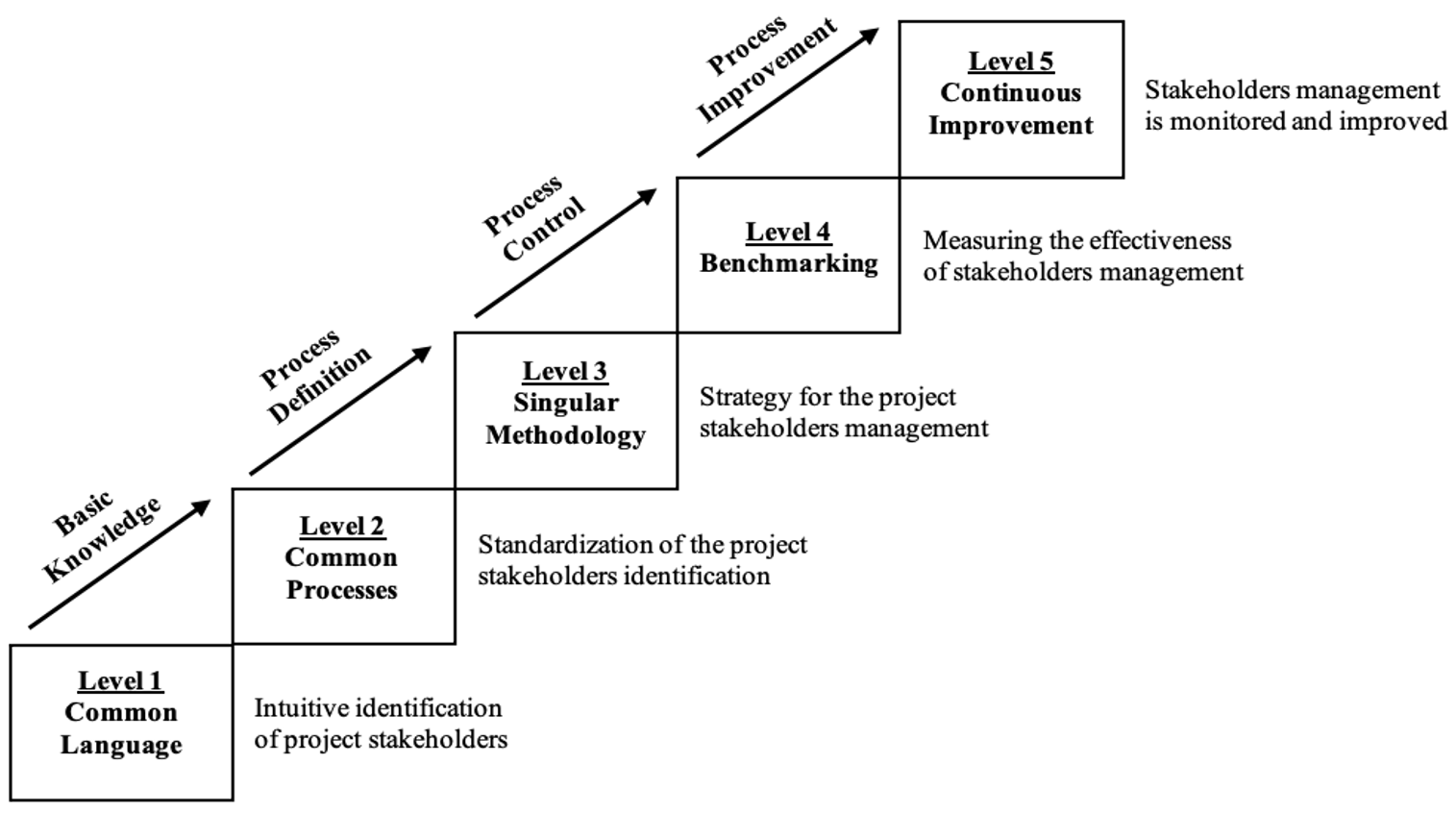

3. Project Management Maturity of Non-Profit Organizations and Stakeholder Management

4. Research Methodology

5. Results

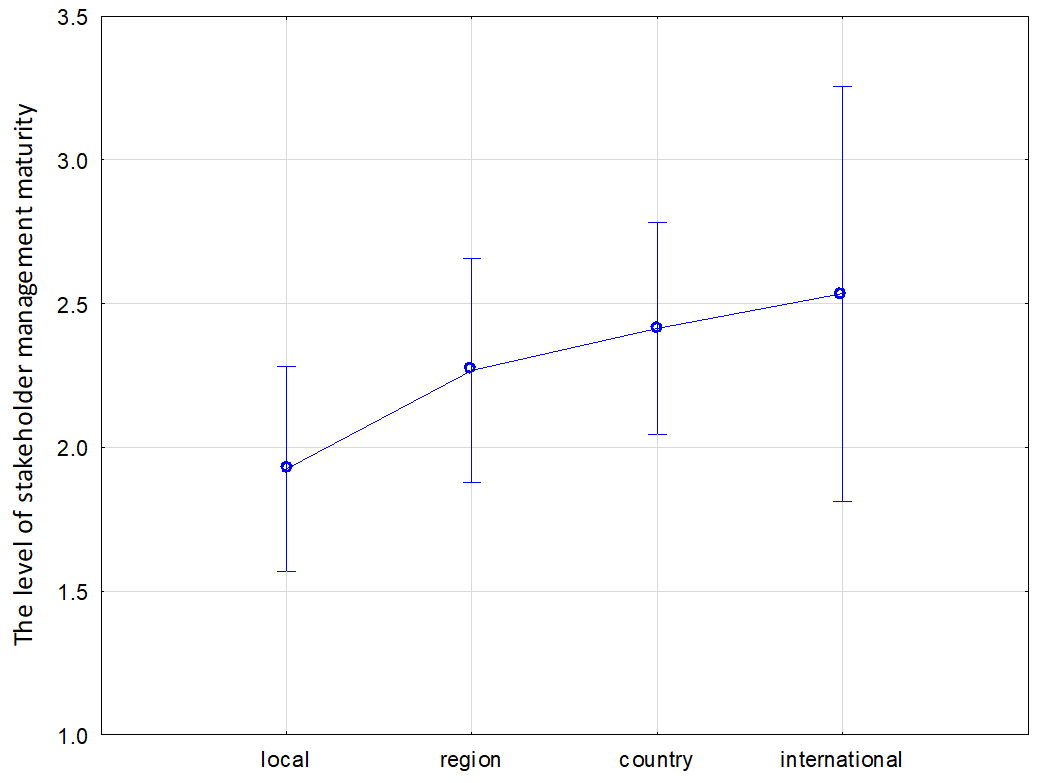

- The geographical scale of the activity;

- Using IT tools to implement projects;

- Assessment of experience in realization projects.

- Whether the organization has developed a formal project management methodology;

- Whether the methodology is used partially or throughout the organization.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

7. Practical Implications and Contribution

8. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gareis, R.; Huemann, M.; Martinuzzi, R.-A. Relating Sustainable Development and Project Management; IRNOP IX: Berlin, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pade, C.; Mallinson, B.; Sewry, D. An Elaboration of Critical Success Factors for Rural ICT Project Sustainability in Developing Countries: Exploring the DWESA Case. J. Inf. Technol. Case Appl. Res. 2008, 10, 32–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrini, F.; Tencati, A. Sustainability and stakeholder management: The need for new corporate performance evaluation and reporting systems. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2006, 15, 296–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, G.S. Information systems project abandonment: A stakeholder analysis. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2005, 25, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standish Group. Chaos Report. 2015. Available online: https://www.infoq.com/articles/standish-chaos-2015 (accessed on 20 April 2021).

- Kramer, R.M. Nonprofit Organizations in the 21st Century: Will Sector Matter? Working Paper Series; Nonprofit Sector Research Fund: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, D. The Management of Non-Governmental Development Organizations; Routledge: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, J. Towards a theory of project management: The nature of the project governance and project management. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2006, 24, 93–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiferaw, A.T.; Klakegg, O.J.; Haavaldsen, T. Governance of Public Investment Projects in Ethiopia. Proj. Manag. J. 2012, 43, 52–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, R.; Lecoeuvre, L. Operationalizing governance categories of projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2014, 32, 1346–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskerod, P.; Huemann, M. Sustainable development and project stakeholder management: What standards say. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2013, 6, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarzecki, D.; Jabłoński, M. Sustainable Value Management–New Concepts and Contemporary Trends Sustainable Value Management–New Concepts and Contemporary Trends; MDPI: Basel, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Carboni, J.; Duncan, W.; Gonzalez, M.; Milsom, P.; Young, M. Sustainable Project Management; The GPM Reference Guide; GPM Global: Novi, MI, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Vaupel, R.; Schmolke, G.; Krüger, A. Customer-Focused Management by Projects; MacMillan Publishers: Basingstoke, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Silvius, G.; Schipper, R. Sustainability in project management. A literature review and impact analysis. Soc. Bus. 2014, 4, 63–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, P.C. Making Nonprofits Work: A Report on the Times of Nonprofit Management Reforms; The Aspen Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sargeant, A.; Shang, J. Fundraising Principles and Practice; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Domański, J. Risk Categories and Risk Management Processes in Nonprofit Organizations. Found. Manag. 2016, 8, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Wang, P.; Bart, C. Board Processes, Board Strategic Involvement, and Organizational Performance in For-profit and Non-profit Organizations. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 136, 311–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gálvez-Rodríguez, M.D.M.; Caba-Pérez, C.; López-Godoy, M. Drivers of Twitter as a strategic communication tool for non-profit organizations. Internet Res. 2016, 26, 1052–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crișan, E.; Dan, M. Revenue Diversification Strategies for Non-Governmental Organizations. Rev. Int. Comp. Manag. 2018, 19, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, N.C.; Neely, D.G.; Slatten, L.A.D. Stakeholder groups and accountability accreditation of non-profit organizations. J. Public Budg. Account. Financ. Manag. 2019, 31, 218–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capability Maturity Model Integration for Development (CMMI-DEV). ver. 1.3; Software Engineering Institute: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Capability Maturity Model Integration CMMI. ver. 1.2, Overview; Software Engineering Institute: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Capability Maturity Model Integration CMMI. ver. 1.1; Software Engineering Institute: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ibbs, C.W.; Kwak, Y.H. Assessing Project Management Maturity. Proj. Manag. J. 2000, 31, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibbs, C.; Reginato, J.M.; Kwak, Y.H. Developing Project Management Capability: Benchmarking, Maturity, Modeling, Gap Analyses, and ROI Studies; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Juchniewicz, M. Achieving excellence in the implementation of projects using project management maturity models. In Project Management-Challenges and Research Results; SGH: Warszawa, Poland, 2016; pp. 35–58. [Google Scholar]

- Jugdev, K.; Thomas, J. Student Paper Award Winner: Project Management Maturity Models: The Silver Bullets of Competitive Advantage? Proj. Manag. J. 2002, 33, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spalek, S. Establishing a Conceptual Model for Assessing Project Management Maturity in Industrial Companies. Int. J. Ind. Eng. Theory Appl. Pract. 2015, 22, 301–313. [Google Scholar]

- Garland, R. Project Governance: A Practical Guide to Effective Project Decision Making; Kogan Page Publishers: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, J.R. The Handbook of Project-Based Management: Leading Strategic Change in Organizations; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Biesenthal, C.; Wilden, R. Multi-level project governance: Trends and opportunities. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2014, 32, 1291–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitsis, T.; Sankaran, S.; Gudergan, S.; Clegg, S.R. Governing projects under complexity: Theory and practice in project management. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2014, 32, 1285–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.F.; Chambers, W.B. The Politics of Participation in Sustainable Development Governance; United Nations Universities Press: Tokyo, Japan, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bingham, L.B.; Nabatchi, T.; O’Leary, R. The New Governance: Practices and Processes for Stakeholder and Citizen Participation in the Work of Government. Public Adm. Rev. 2005, 65, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osti, R. Forms of community participation and agencies’ role for the implementation of water-induced disaster management: Protecting and enhancing the poor. Disaster Prev. Manag. Int. J. 2004, 13, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourne, L.; Walker, D.H. Project relationship management and the Stakeholder Circle™. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2008, 1, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofori, D.F. Project Management Practices and Critical Success Factors–A Developing Country Perspective. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2013, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Eskerod, P.; Huemann, M.; Savage, G. Project Stakeholder Management—Past and Present. Proj. Manag. J. 2015, 46, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, A.; Naaranoja, M.; Savolainen, J. Project change stakeholder communication. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2016, 34, 1579–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerzner, H. Strategic Planning for Project Management Using a Project Management Maturity Model; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Jalocha, B.; Bogacz-Wojtanowska, E. The bright side of social economy sector’s projectification: A study of successful social enterprises. Proj. Manag. Res. and Pract. 2016, 3, 5043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goedknegt, D.; Silvius, A.J.G. The Implementation of Sustainability Principles in Project Management. In Proceedings of the 26th IPMA World Congress, Crete, Greece, 29–31 October 2012; pp. 875–882. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E.; McVea, J. A stakeholder approach to strategic management. In Handbook of Strategic Management; Hitt, M., Harrison, J., Freeman, R.E., Eds.; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsch, L.S. Portfolios of Control Modes and IS Project Management. Inf. Syst. Res. 1997, 8, 215–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relich, M.; Bzdyra, K. Estimating New Product Success with the Use of Intelligent Systems. Found. Manag. 2014, 6, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beringer, C.; Jonas, D.; Gemünden, H.G. Establishing Project Portfolio Management: An Exploratory Analysis of the Influence of Internal Stakeholders’ Interactions. Proj. Manag. J. 2012, 43, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daigneault, P.-M.; Jacob, S.; Tremblay, J. Measuring Stakeholder Participation in Evaluation: An Empirical Validation of the Participatory Evaluation Measurement Instrument (PEMI). Eval. Rev. 2012, 36, 243–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PMI. A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge, 5th ed.; PMBOK: Newtown Square, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- PMBOK® Guide. A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge; PMBOK: Newtown Square, PA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Akhter, S.; Akingbola, K.; Domaradzka-Widla, A.; Kristmundsson, O.K.; Malunga, C.; Sasson, U. Leadership and management of associations. In The Palgrave Handbook of Volunteering, Civic Participation, and Nonprofit Associations; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 915–949. [Google Scholar]

- Domański, J. The Analysis and Synthesis of Strategic Management Research in the Third Sector from Early 2000 Through to Mid-2009. Found. Manag. 2011, 3, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Domanński, J. Competitiveness of nongovernmental organizations in developing countries: Evidence from Poland. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2012, 41, 100–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grucza, B. Project stakeholder analysis models. In Project Management-Challenges and Research Results; SGH: Warszawa, Poland, 2016; pp. 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Rowlinson, S.; Cheung, Y.K.F. Stakeholder management through empowerment: Modelling project success. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2008, 26, 611–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khang, D.B.; Moe, T.L. Success criteria and factors for international development projects: A life-cycle-based framework. Proj. Manag. J. 2008, 39, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ika, L.A.; Diallo, A.; Thuiller, D. Critical success factors for World Bank projects: An empirical imvestigation. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2012, 30, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermano, V.; Lopez-Paredes, A.; Cruz, N.M.; Pajares, J. How to manage international development (ID) projects successfully. Is the PMD Pro1 Guide going to the right direction? Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2013, 31, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golini, R.; Kalchschmidt, M.G.M.; Landoni, P. Adoption of project management practices: The impact on international development projects of non-governmental organizations. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2015, 33, 650–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PMI. A Project Management Body of Knowledge; Project Management Institute: Newtown Square, PA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Schlichter, J. Surveying project management capabilities. PM Netw. 1999, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Kerzner, H. Applied Project Management; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kerzner, H. Using the Project Management Maturity Model: Strategic Planning for Project Management, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Skumolski, G. Project Maturity and Competence Interface. Cost Eng. 2001, 43, 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, E.S.; Jessen, S.A. Project maturity in organisations. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2003, 21, 457–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillson, D. Assessing Organizational Project Management Capability. J. Facil. Manag. 2003, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Capability Maturity Model Integration (CMMI)-Continuous Representation; Software Engineering Institute: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2003.

- Litke, H.D. Projektmanagement Methoden, Handbuch fur die Praxis; Hanser Verlag: Munchen/Wien, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke-Davies, T.J.; Arzymanow, A. The Maturity of Project Management in Different Industries: An Investigation into Variations between Project Management Models. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2003, 21, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, A.; Moultrie, J.; Clarkson, P. Assessing Organizational Capabilities: Reviewing and Guiding the Development of Maturity Grids. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2011, 59, 138–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poppelbub, J.; Roglinger, M. What Makes a Useful Maturity Model? A Framework of General Design Principles for Maturity Models and Its Demonstration in BPM, ECIS 2011 Proceedings. Paper 28. 2004. Available online: http://aisel.aisnet.org/ecis2011 (accessed on 12 April 2021).

- Crawford, L. Global body of project management knowleddge and standards. In The Wiley Guide to Managing Projects; Morris, P., Pinto, J.K., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; pp. 1150–1196. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, J.K. Project Management Maturity Model, 3rd ed.; Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, R.C.; Chin, C.M. Project Management Guide and Project Management Maturity Models as Generic Tools Capable for Diverse Applications. In Diverse Applications and Transferability of Maturity Models; Katuu, S., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 269–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge, 4th ed.; Project Management Institute: Newtown Square, PA, USA, 2008.

- Hausner, J. Social economy and development in Poland. In The Social Economy: International Perspectives on Economic Solidarity; Zed Books: London, UK, 2009; pp. 208–232. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/ncbr-en (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Available online: https://www.funduszeeuropejskie.gov.pl/en/ (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Prokopy, L.S. The relationship between participation and project outcomes: Evidence from rural water supply projects in India. World Dev. 2005, 33, 1801–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njogu, E.M. Influence of Stakeholders Involvement on Project Performance: A Case of Nema Automobile Emmission Control Project in Nairobi County, Kenya; Unpublished MBA Project; University of Nairobi: Nairobi, Kenya, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mkutano, S.M.; Sang, P. Project management practices and performance of non-governmental organizations projects in Nairobi City County, Kenya. Int. Acad. J. Inf. Sci. Proj. Manag. 2018, 3, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Musyula, P. Factors Affecting the Performance of Nongovernmental Organizations in Kenya: A case of Action Aid International. 2014. Available online: http://erepo.usiu.ac.ke. (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Nombo, N.M.; Nyangarika, A. Challenges Facing Non-Governmental Organization Stakeholders’ Participation in Educational Project, International Journal of Advance Research and Innovative Ideas. Education 2020, 6, 104–114. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin, A.L. Stakeholder Engagement; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Späth, L.; Scolobig, A. Stakeholder empowerment through participatory planning practices: The case of electricity transmission lines in France and Norway. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2017, 23, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Neshkova, M. Citizen Input in the Budget Process: When Does It Matter Most? Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2013, 43, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbsleb, J.; Zubrow, D.; Goldenson, D.; Hayes, W.; Paulk, M. Software quality and the Capability Maturity Model. Commun. ACM 1997, 40, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Project Management Maturity Level | Stakeholder Management Maturity Level |

|---|---|

| Level 1 Use of common terminology Use of common terminology by members of project teams. At this level, there are organizations that recognize the importance of projects, but are only starting to be aware of the need for a common understanding of principles and concepts related to project management. The management supports the implementation of projects in a chaotic manner. There is no training in the area of project management. Moreover, the benefits of project management are not identified. | Individual project stakeholders are identified, it is not a formal process. Project promoters see the need to identify stakeholders, but do not yet see the benefits of this process. Singular attempts are made to use tools in single projects. These are solutions implemented and combined with the manager. |

| Level 2 Unified processes Common processes in project management. There is an improvement in processes that lead to an increase in the chances of the success of a given project. Importantly, these processes are common to all projects carried out in the organization. At this level, the benefits of implementing projects in the organization are also noticed. This translates into supporting projects at every management level. | There is a stakeholder identification process. There are attempts to standardize this process. The influence of this group on the success of the project is being notices, but only from the point of view of individual projects. Instructions and procedures are created to a limited extent. IT tools supporting stakeholder management are used to a limited extent. |

| Level 3 Developed methodology of the procedure It uses the synergy effect that results from combining all methodologies into one common methodology. This enables easier control of the entire project management process. The organizational culture is also shaped in the direction of project management and bureaucracy is reduced to the necessary minimum. At this level, comprehensive and periodic training in the area of project management takes place. Moreover, project management is officially supported by the management at every management level. | There are processes aimed at identifying stakeholders. They are analyzed and assessed, prioritization is carried out, and errors that have appeared in already completed projects are analyzed. Stakeholder engagement plans are prepared, along with an indication of a strategy to deal with them. The engagement process is carried out primarily with the stakeholders with the greatest impact on the project. Trainings are conducted and procedures are followed. The benefits of using stakeholder management tools are recognized. |

| Level 4 Benchmarking Application of benchmarking in project management. At this level, benchmarking is used as a tool that supports development decisions. This is an ongoing process. The organization has a permanent staff that carries out continuous improvement processes. Benchmarking refers to the processes carried out, methods and techniques used as well as soft aspects of management, such as organizational culture, personal skills. The organization at this level has a project office or center of excellence as the focal point of project knowledge in the organization. | Processes aimed at measuring the effectiveness of the applied stakeholder management methods and the benefits of this are implemented. The level of maturity also relates to the soft aspects of project management, which means that the communication plans adopted in the project also become a stakeholder management tool. The processes are analyzed on an ongoing basis, improved and adjusted to the specifics of implemented projects. |

| Level 5 Continuous improvement Continuous improvement. At this level, as a result of benchmarking, organizations make decisions regarding the usefulness of the information obtained in improving their own project management methodology. They constantly follow trends in project management, technological innovations or look for improvements in implemented processes. The knowledge gained during the implementation of projects is transferred to subsequent projects and made available to project teams in the future. In addition, the organization has a mentoring program for project managers, usually implemented by a project office. Strategic planning through project management is an ongoing process. This is the stage in which there is a continuous process of improving project implementation. | All processes related to stakeholder involvement in project ventures are in place. They are standardized and monitored. This is the level at which project management is an ongoing process. This means that the entire stakeholder management process is subject to detailed analysis and evaluation. The conclusions regarding the improvement of this process as a whole in future projects (good practices) become important here. The organization uses an integrated approach to CSR. |

| Independent Variable | Impact on the Dependent Variable, Stakeholders p-Value | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Number of implemented EU projects | 0.18 | Variables have no effect |

| Number of all completed projects | 0.97 | |

| Period of activity in the field of project implementation (in years) | 0.77 | |

| Model fit R2 = 0.02 p-value = 0.53, dependencies do not exist | ||

| Stakeholders | ||

|---|---|---|

| Independent Variable | Coefficient of Correlation of the Dependence of the Independent Variable and the Stakeholders Variable | Statistical Significance |

| Number of implemented EU projects | −0.05 | p-value = 0.54 |

| Number of all completed projects | −0.14 | p-value = 0.14 |

| Period of activity in the field of project implementation (in years) | −0.02 | p-value = 0.79 |

| Influence of the Variable | p-Value | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| The scale of the organization’s activities | 0.25 | None of the analyzed factors has an impact on the level of stakeholder management maturity. |

| Experience in project implementation (low-high) | 0.30 | |

| The use of IT methods in the implementation of projects | 0.35 | |

| Training in project implementation for employees | 0.15 |

| Factor | Average Value Stakeholders Assessments | p-Value | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| There is no common project management methodology in the organization | 1.9 | 0.002 | The introduction of project management methodology in an organization has a major impact on the way stakeholders are managed |

| The organization has a standardized project management methodology | 2.5 | ||

| Project management methodology introduced in part of the organization | 2.2 | 0.01 | The partially (fragmentarily) applied methodology is ineffective The methodology applicable throughout the organization allows one to significantly increase the level of maturity of stakeholder management |

| Project management methodology implemented throughout the organization | 2.6 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brajer-Marczak, R.; Marciszewska, A.; Nadolny, M. Selected Determinants of Stakeholder Influence on Project Management in Non-Profit Organizations. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8899. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168899

Brajer-Marczak R, Marciszewska A, Nadolny M. Selected Determinants of Stakeholder Influence on Project Management in Non-Profit Organizations. Sustainability. 2021; 13(16):8899. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168899

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrajer-Marczak, Renata, Anna Marciszewska, and Michał Nadolny. 2021. "Selected Determinants of Stakeholder Influence on Project Management in Non-Profit Organizations" Sustainability 13, no. 16: 8899. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168899

APA StyleBrajer-Marczak, R., Marciszewska, A., & Nadolny, M. (2021). Selected Determinants of Stakeholder Influence on Project Management in Non-Profit Organizations. Sustainability, 13(16), 8899. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168899