1. Introduction

Sustainability is challenging because people are often drawn to selfish behaviors with specific short-run benefits (e.g., profits, convenience) rather than pursuing actions with broad outcomes that serve collective, long-term interests [

1,

2]. To respond to these dynamics, we propose integrating nature, communities, and belief systems into the self-concept, which is people’s psychological understanding of themselves (e.g., their traits, relationships, group identities, defining attributes) and the organization of that self-relevant knowledge [

3,

4]. As entities (e.g., close others, belief systems, nature) become integrated in the self-concept, they motivate people’s behaviors [

5,

6]. For example, when people develop romantic relationships, they typically integrate their partner into their self-concepts, becoming more committed to caring for that person and even blurring distinctions between themselves and their partner [

7,

8]. Because associations with one’s self-concept drive human behavior (e.g., people will forego selfish gains to care for others included in their sense of self), many scholars and practitioners have focused on using the self to promote pro-environmental outcomes. In this review paper, we discuss several approaches that have encouraged conservation efforts, and then we describe our Triadic Framework, which integrates and synthesizes several approaches that include combinations of nature, communities, belief systems, and self-knowledge into a comprehensive, interconnected approach to promote sustainability. Rather than providing a comprehensive review of a particular research literature, we draw on several domains of relevant work from biology, psychology, and field conservation to forward a new framework to promote sustainability efforts. We conclude our paper by discussing an effective real-world application of this framework, and then we invite readers to employ the Triadic Framework for addressing sustainability challenges in their own communities.

People are more committed to conservation when they include nature in their self-concepts to a greater degree [

9], when they view the self as relatively smaller than nature [

10], and when they feel strong self-relevant emotions such as guilt [

11] or awe [

12] in response to nature. For example, the inclusion of nature in self scale adapted Aron et al.’s [

7] measure of inclusion of others in self by replacing romantic partner with “nature” and asking people how integrated nature is in their self-concepts by reporting how much overlap there is between two circles, one depicting the self and the other representing nature. As people had greater inclusion of nature in self (i.e., greater overlap between the self and nature circles), they were more committed to protecting the environment [

9]. These programs of research have established that the self-concept and its relations to nature can encourage greater sustainability, yet this past work has viewed associations between the self and nature in a relatively direct fashion. For example, work on identity [

13] and on inclusion of nature in self [

14] has focused on the extent to which people report self-nature connections. Accordingly, people have promoted biophilia or love of nature [

15], greater connectedness to nature [

16,

17], or exposure to nature [

18] to produce pro-environmental behaviors. Thus, protecting nature requires more than having positive attitudes toward the environment—it requires integrating nature into one’s self-concept.

Other fruitful conservation approaches have considered direct connections between the self and communities, places, and belief systems. For instance, conservation efforts are more successful when they include local community members’ perspectives [

19], prioritize personal relationships toward shared conservation outcomes [

20], and promote local community involvement [

21]. Additionally, the well-studied topic of place attachment [

22] is founded in personal experiences [

23] and highlights a range of important self-place connections from utilitarian land use links to deep-rooted familial associations [

24]. Place connections can drive positive conservation actions for natural areas [

25,

26,

27] and predict pro-environmental behaviors [

28]. To be most effective, personal conservation benefits need to both outweigh the sustainability action efforts required and align with local social norms for success [

29]. Research has shown that greater sustainability outcomes can be realized when conservation efforts take into account people’s connections to species, communities, and places [

30]. Finally, people who hold biospheric goals and ideals [

9,

31] and self-transcendent values [

10,

32] are more committed to conservation as well.

To attract support for conservation and to move larger groups of people toward sustainable conservation actions require nested approaches [

21] that enmesh interdisciplinary best practices [

33,

34]. For example, the well-recognized polar bear (

Ursus maritimus) has served as a charismatic icon for species-based conservation efforts, as a beacon to promote broader ecosystem conservation of the Arctic, as a well-loved animal to elicit financial support for environmental causes, and as an ambassador to support climate change solutions throughout the world. Charismatic megafauna can spur pro-environmental engagement from the public, although ironically, these beloved species still face imminent extinction despite the additional attention they receive [

35]. Thus, it is clear that additional approaches are necessary for successful sustainability efforts.

In the current paper, we highlight how connections between the self and nature, community, and belief systems have tremendous value for encouraging sustainable practices. Rather than simply strengthening associations between the self and nature or between the self and communities, we propose that forging multiple concurrent and mutually reinforcing interconnections within the self-concept can produce stronger, more sustained pro-environmental engagement. We discuss the conceptual underpinnings of this framework, elaborate on its properties and implications, and discuss a successful real-world application that supports sustainability in the Western Ghats of India. Our approach is grounded in illustrative, field conservation initiatives and in psychology, biology, and interdisciplinary theoretical perspectives, which we hope lends this framework for further use in scholarly, educational, and field-based contexts that can support everyday conservation efforts. Accordingly, our review is not intended to be exhaustive (each of these research streams is very expansive and well beyond the scope of any one paper), but rather, it draws upon several different literatures to develop an integrative, interdisciplinary approach that offers practical solutions and establishes theoretical bridges between and among these distinct scholarly domains.

2. The Triadic Framework to Sustainability

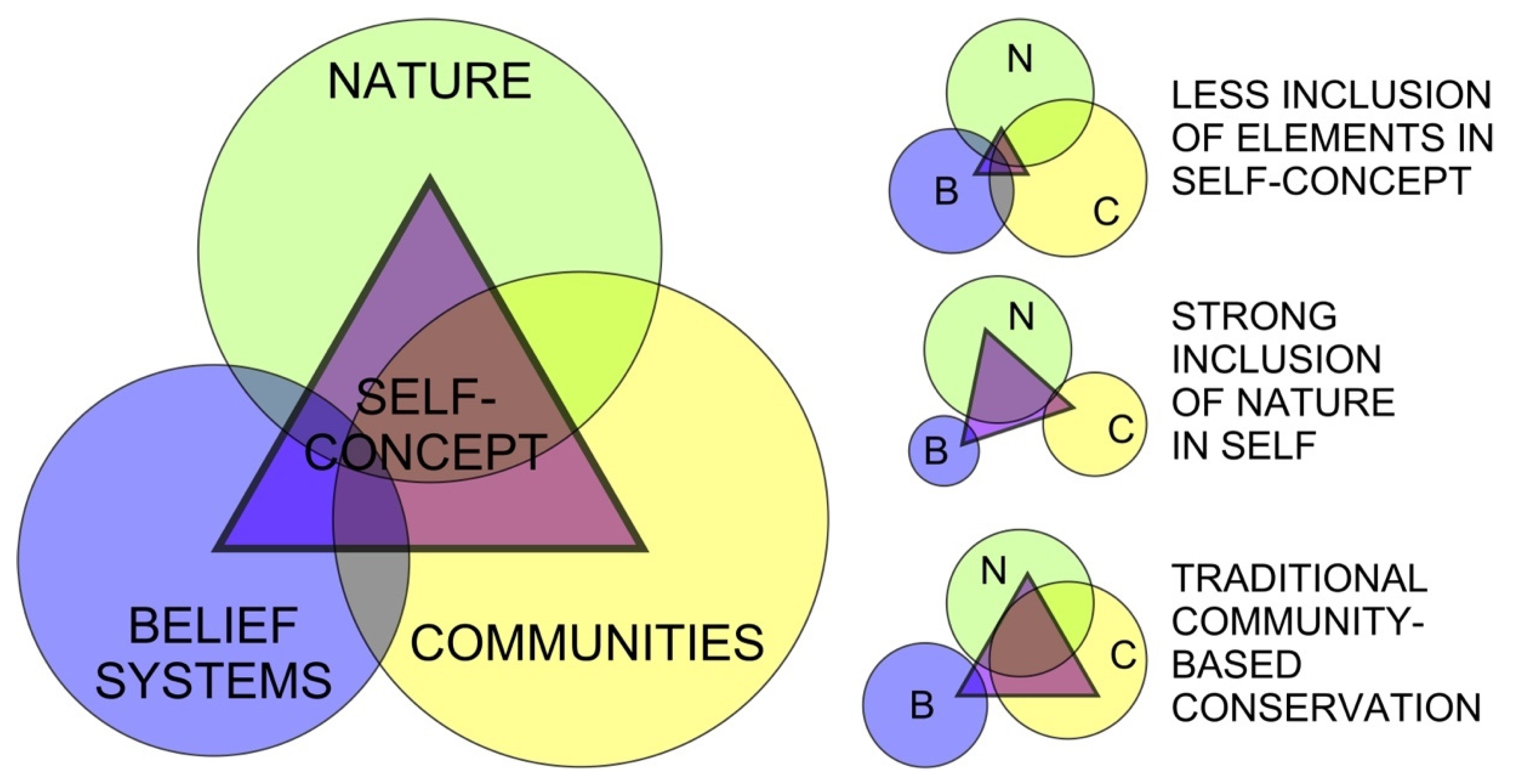

Long-term progress on sustainability requires associating the self with elements that support pro-environmentalism. Rather than focusing on just the elements themselves (e.g., knowledge about a species) or on bivariate connections with the self (e.g., inclusion of nature in the self), we approach integrating the self-concept into a dynamic triad of interconnections with nature, communities, and belief systems (see

Figure 1).

Let us consider some important definitions and features of our model in the context of sustainability. First, “nature” captures both the idea of specific plant and animal species and broader aspects of the environment. Thus, examples of nature may include a forested city park, a conservation project reintroducing a native species of birds into a habitat, or a flower box that attracts pollinators. “Communities” reflects collective social groups with a perceived shared sense of place or vision (thus, they are psychological in nature). For example, local residents living in proximity, collections of scientists with similar professional interests, or hobbyists who share an affinity for a particular species could each be considered a community. The third element, “belief systems,” captures people’s broader ideologies such as spiritual, religious, cultural, scientific, place-based, or philosophical general knowledge. Belief systems often incorporate personal values, social norms, and moral frameworks that inform and direct behavior. These elements can vary in size (reflecting their availability to one’s self-concept), and they can overlap with each other considerably (e.g., conservationists working to preserve a watershed based on a common scientific framework; see left panel of

Figure 1) or they may have no overlap at all (e.g., a coastal community indifferent to the plight of an endangered fish species off its shores; illustrated by the lack of circle overlap in the middle right panel of

Figure 1). The degree of overlap resides along a continuum, and as these three elements share greater overlap with each other, the potential for interrelated and mutually reinforcing pro-environmental action grows. In this framework, we assume positive relations among the elements (e.g., a community interested in saving a species rather than hunting it to extinction) because of our interest in sustainable conservation outcomes.

In addition to considering how these three elements have varying degrees of overlap, the other key aspect of this framework involves the self-concept (the triangle). The triangle reflects the portion of one’s self-concept that is associated with these three elements but not the entirety of one’s sense of self. That is, one’s self-concept can have many facets completely unrelated to nature, communities, and belief systems, but in the current work, we focus on areas where one’s sense of self relates to these three elements. Indeed, self-concepts are composed of multiple, context-dependent selves [

36] and herein we focus on the aspects of the self that implicate nature, communities, and belief systems related to sustainability. To the extent that one’s self-concept shares overlap with each of the three elements (i.e., a triangle that has more overlap with the three circles), it reflects greater integration of each element in one’s sense of self. In the left panel of

Figure 1, we see that this person has a lot of self-concept overlap with nature (e.g., nature connectedness) and with communities (e.g., importance of ingroup membership), and relatively less overlap with beliefs (e.g., lower importance on belief systems such as science or spirituality related to sustainability for defining the self). On the other hand, the top right panel of

Figure 1 illustrates a person whose self-concept has very little integration with the three elements even though the elements have the same proportions of overlap with each other compared to the left panel of

Figure 1.

In sum, the Triadic Framework incorporates two important and distinct components. First, it considers the interrelations among nature, communities, and belief systems (i.e., the overlapping circles in

Figure 1), anticipating that greater interconnectedness among these three elements establishes the foundation for greater sustainability. Second, it contends that stronger connections between these elements and the self-concept (the triangle) enhances pro-conservation motivations by increasing the self-relevance of these elements. We now focus on exploring the individual elements of our Triadic Framework, identifying examples and documenting connections with several existent literatures. Afterwards, we discuss the importance of interconnections among these elements that help support conservation efforts and expand on how the overlap among them coupled with their integration in one’s sense of self is critical for promoting sustainability.

2.1. Nature

Nature has always been at the center of ecological conservation, although how conservationists have approached saving ecosystems and their species has changed across time. Global flora and fauna populations, threatened primarily by human-induced habitat degradation, result in environments with less biodiversity and compromised resilience [

37] Typically, once negative environmental impacts are identified, people work to mitigate them by addressing the threat and restoring habitats that include the endangered species. Charismatic, keystone species within conservation areas bring attention to the plight of these species and can attract further support [

38] including funding for broader ecosystem-based conservation efforts [

39]. Despite defining only part of the overall conservation story, nature remains a key driver in any conservation biology effort.

Conservation is heavily dependent on local context and people. Through participation in conservation efforts, focal species and natural areas become more important to people, leading to greater inclusion of nature in self [

9], greater connectedness to nature [

16], increased empathy for species [

40], stronger biophilia [

15], more commitment to nature [

41] greater biospheric value orientations [

31] or more nature relatedness [

42]. For example, in areas of Thailand with significant human–elephant conflict, after deterrent methods were employed (beehive fences to prevent incursions from crop-raiding elephants on farmlands), local residents developed more positive views of elephants [

43]. In fact, merely watching videos of nature increases people’s willingness to participate in sustainability efforts because they experience greater inclusion of nature in self [

18]. Thus, focusing on nature can increase people’s self-nature connections, which in turn, promote conservation actions.

2.2. Communities

Communities are composed of networks of intergenerational, personal, and familial connections, and they are at the heart of sustainability efforts. Community focuses the conservation lens on people as part of the ecosystem [

33], offering an opportunity to redistribute power and reduce conflicts that stall sustainability [

44] and keep people working on common causes. There are exceptional examples of communities co-leading and participating in conservation efforts globally [

45,

46] encouraging equity and successful conservation [

20]. If single community representatives take part in an international conservation effort rather than relying on many community members, the work can suffer because the activities can quickly focus on only one individual’s ideals rather than considering collective perspectives [

47]. Inclusion of communities and valuing group relationships are critical for sustainable conservation.

In well-developed efforts, community members serve as guardians in local conservation activities [

46,

48], tying directly to their self-concepts. For example, local residents in Belize were asked about personal connections to nature with some describing utilitarian, practical uses for the land. Interestingly, nearly all Belizeans interviewed also described personal emotional experiences such as gaining peace, experiencing happiness, and finding inspiration from these important natural areas [

30]. These guardian roles can also foster stewardship in conservation efforts. For instance, the Three Mountain Alliance [

49] on Hawai’i island enlists students to be “forest guardians” by participating in service-learning conservation projects (e.g., planting endangered native tree species to combat invasive species), which serves to increase each student’s commitment to maintaining threatened ecosystems on the island.

Communities are powerful in motivating people because collective identities serve one of the most powerful fundamental human needs, belongingness [

50]. Moreover, communities are often a meaningful source of ingroup identification [

51,

52] and people seek out social connections to restore interpersonal interrelatedness [

53,

54,

55]. Thus, people’s connections to others influence behavior, and when communities support sustainable practices, individuals will be especially motivated to contribute to those efforts to maintain and enhance their social connectedness with the collective.

2.3. Belief Systems

Belief systems can include a broad range of interrelated individual values, moral principles, scientific knowledge, cultural ties, social norms, religious influences, and spiritual connections, and thus they offer insights into different world views, cultural connections, and social traditions. For example, when belief systems include community taboos to not enter or take from a natural area, these protected environments display high levels of species biodiversity [

56].

Regardless of whether one’s belief systems incorporate religious, philosophical, or scientific principles, this knowledge is critical for directing people’s behaviors [

57,

58,

59]. People typically pursue behaviors based on broad belief systems (e.g., valuing social justice over individual gain, core religious tenets, valuing science over other anecdotal knowledge) rather than extensively weighing the pros and cons of any particular course of action. For example, Buddhist teachings feature many stories based in natural settings that encourage pro-environmental action and care [

60]. Thus, people’s general belief systems and implicit knowledge are important for determining behavior in ambiguous situations or in contexts where motivation to deliberate on actions is low [

61,

62] and they play an important role in directing conservation action in particular [

31,

32,

63].

One of the strengths of the Triadic Framework is that it views belief systems, nature, and communities as interrelated elements and as integrated into one’s sense of self. It is these interrelationships that promote sustainability in qualitatively powerful ways. Past conservation approaches have typically only considered simple relations (e.g., self and nature, nature in communities), but the power of the Triadic Framework is revealed when these elements are strongly interrelated and mutually support sustainability, which in turn becomes more motivating when they are integrated into one’s self-concept. Now, we examine the intersections among the three elements that can support sustainability.

2.4. Nature–Communities Intersection

The nature–communities intersection is well represented by the field of community-based conservation (bottom right panel of

Figure 1) whereby sustainability is created in consultation by, for, and with community members [

64]. Ideally, community-based conservation engages local residents in all aspects of conservation efforts rather than having a top-down plan imposed from outsiders (e.g., governmental agencies, foreign scholars). By encouraging community engagement, residents bring local experiences to bear on improving conservation plans and they become active stewards with a stake in sustainability success, which deepens their commitment to nature.

For example, the Community Baboon Sanctuary (CBS) in Belize exemplifies strong nature–community integration. At the CBS, local tourism practices were set in place to highlight and maintain a healthy regional Yucatan black howler monkey (

Alouatta pigra) population [

65]. Initially, local residents were involved with conservation efforts by agreeing to set aside private property as part of a collective land management plan to maintain contiguous sections of forested riverbanks as habitat for these primates. Over the years, the CBS has further promoted community involvement by establishing host family lodging opportunities and touring opportunities guided by residents, attracting more visitors and providing more opportunities for local residents. As a result, the CBS has involved local residents in conservation efforts, provided new material benefits for community members and made nature preservation a key element of community identity. Thus, the community is concerned about protecting nature, and nature benefits the community, reflecting considerable nature–community overlap.

2.5. Nature–Belief Systems Intersection

Most scholars argue that nature has inherent value and that connections to personal belief systems enhance it. Spiritual animal connections from primates to wolves and from birds to ants exist in different professions, cultures, and places. This species–spiritual connection is illustrated by many writers who inspire biophilia [

15], encouraging people to learn more about animals and to make personal connections with them. For example, Goodall [

66] provided an insider’s look at chimpanzee life, Leopold [

67] and Lopez [

68] brought readers closer to wolves, Matola [

69] offered an intimate view of why the last few scarlet macaws matter, and countless traditional stories passed orally shed light on these intimate nature obsessions and serve to build stronger personal connections with them.

Nature–belief system relations can foster novel sustainability approaches. In an example on Hawai’i island, the ‘Alalā (

Corvus hawaiiensis) holds cultural importance to some families as a family spiritual guardian [

70]. Successful captive breeding programs have brought this species back from extinction along with a resurgence of belief systems (e.g., cultural traditions) such as revived cultural storytelling and creating art about the ‘Alalā to enhance community support for these conservation efforts. Indeed, highlighting belief systems through natural connections elevates community conservation actions and supports species preservation.

2.6. Communities–Belief Systems Intersection

Communities benefit from sustainability in many ways, and the Triadic Framework can expand community interactions (e.g., for individuals, among stakeholder groups) as deeper knowledge about nature and local cultural practices develop [

38,

46,

71]. Conservation practitioners can gain a more elaborated understanding of local spiritual connections to a place, and community members can further their knowledge of how species diversity improves ecosystems. Moreover, outside scholars with extensive collective knowledge of sustainability can develop trust with and respect for local community members [

72], promoting additional conservation work together (e.g., local communities will want to partner with experts to create and support additional sustainability efforts when mutual trust and respect exist).

Community–belief system connections are well represented in culturally important sites such as numerous western U.S. national parks created to promote tourism and further cultural understanding. Belief systems not only include spiritual or cultural practices, but they can include scientific knowledge too. One successful example involves saving the California Condor (

Gymnogyps californianus) from extinction [

73]. In the 1980s, fewer than 30 California Condors remained alive in the wild. In response, zookeepers undertook a breeding program and leveraged their scientific knowledge of what was killing condors (e.g., exposure to pesticides, lead bullets lodged in the carcasses that condors feed upon) to help the birds recover. Today, there are more than 500 California Condors in the wild [

74]. In this example, a community of zookeepers used their scientific beliefs to save this species from extinction.

3. The Triadic Framework in Action

So far, we have discussed the value of the individual elements of the triad (i.e., nature, communities, belief systems), how these elements can be integrated with one’s self-concept (e.g., inclusion of nature in self), and how two different triad elements can overlap with each other (e.g., community-based conservation, spiritual connections with nature). However, the value of the Triadic Framework is most revealed when 1) all three elements are interrelated and 2) these overlapping elements share strong associations with one’s sense of self. In such cases, sustainability is greatly enhanced because the elements mutually reinforce each other and their connections to one’s self-concept strengthens conservation motivation. We now turn to an example that illustrates these principles well.

The Western Ghats, India, is a coastal, mountainous region recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site for its unique ecological features such as the richness of endemic species known only to live there, ancient land forms (its mountains are older than the Himalayas), and its distinctive monsoon weather patterns [

75]. The Western Ghats houses 2% of the Earth’s global biodiversity, with an abundance of ecologically and culturally important species including over 600 bird and 5000 plant species—some of which are threatened or endangered. Despite this notoriety, few conservation initiatives are focused on the Western Ghats. One exception is the exemplary work of the Applied Environmental Research Foundation (AERF) India, which began conservation work in the Western Ghats in 1994.

Our Triadic Framework is well illustrated in the Western Ghats by AERF, where species, deities, and communities are the focus of its efforts. AERF supports conservation science approaches focused on important plant and animal species while acknowledging the natural areas that house these species belong to local communities with their own belief systems. The sites where these conservation activities take place are around rural villages with Hindu temple sites (an example being the Keshavraj Temple, see

Figure 2). The areas around these sites, known as sacred groves, are patches of land surrounding these temples where long-standing cultural and religious prohibitions against disturbing the area have resulted in mature forests that have remained relatively untouched [

76,

77].

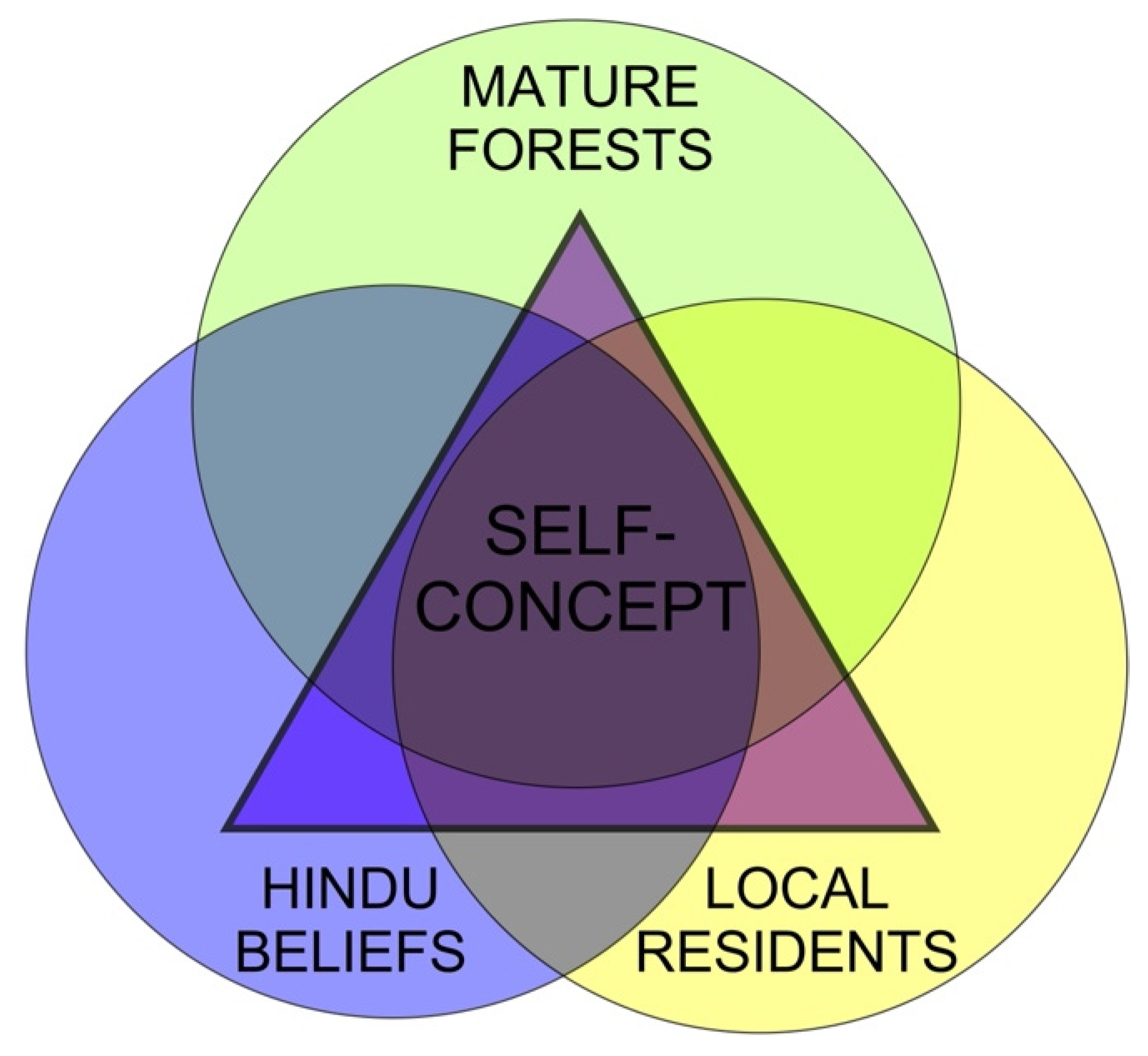

As shown in

Figure 3, these sacred groves show highly interrelated natural areas (mature forests), communities (residents of local villages), and belief systems (Hindu deities and values). In these sacred groves, religious reverence and spiritual taboos against hunting and harvesting from the sites have protected these mature forests from poaching, habitat degradation, and commercialization. Additionally, because these temples are frequented by community members to perform Hindu rituals, local residents help protect the sacred groves from abuse (e.g., logging, hunting, and trash). Protected mature forests within sacred groves support biodiversity lacking in non-grove areas such as the iconic threatened great hornbill (

Buceros bicornis) and the plants hornbills feed on. Across India, there are more than ten thousand sacred groves, which have resulted in a serendipitous patchwork of safeguarded ecosystems [

78].

However, modernity has begun to encroach on these sacred groves, demanding new approaches to conservation. Cultural beliefs and community connections to these temples have been changing over time, and traditional conservation value linkages are disintegrating (e.g., temples fall into disrepair as younger community members move to cities, less commitment to cultural beliefs makes harvesting natural materials in these forests more appealing). The work of AERF brings intrinsic values back into the cultural ethos to see nature as central to self identity through understanding the roles these critical plant and animal species play in ecosystems and local communities. Further, viewing these temples as important fixtures of community life strengthens community–belief system ties. When local residents maintain their commitment to these temples, the mature forests remain protected because of cultural traditions about protecting the sacred groves. Finally, as the importance of local community, Hindu belief systems, and the sacred groves grows, connections between the three elements and people’s self-concepts are strengthened, resulting in greater sustainability. As a result, there is a great deal of overlap among the Triadic Framework elements in the Western Ghats, resulting in mutually reinforcing sustainability outcomes (e.g., local residents value their Hindu heritage, and those spiritual practices help to maintain the integrity of the ecosystem, which in turn supports the quality of life for community residents). Moreover, because community members’ self-concepts are strongly connected to these triad elements, the local residents are especially motivated to protect the sacred groves.

AERF embodies the Triadic Framework by further addressing other community issues (e.g., lack of electricity) and includes culturally-relevant community solutions that fit the local environment (e.g., providing fuel-efficient bio-stoves that reduce the appeal of harvesting firewood from sacred groves for cooking needs). Additionally, recognizing that conservation livelihoods also support healthy ecosystems, AERF underwent rigorous certifications to partner with local communities interested in marketing non-forest timber products such as nuts, fruits, and highly valued medicinal plants. The ability for local community members to benefit both financially (e.g., selling items from the area that do not harm the ecosystem) and spiritually (e.g., renewing their sense of connection to the sacred groves by maintaining local temples) helps connect their self-concepts to nature (the sacred groves), communities (sharing responsibility for the sacred groves with neighbors), and belief systems (affirming Hindu practices). The work of AERF in these villages also integrates new knowledge from science (e.g., the value of the sacred groves for broader ecological services such as providing clean drinking water to villages) with Hindu–nature belief systems, all while maintaining the importance of the community in protecting the long-term vitality of sacred groves.

AERF’s work with sacred groves in India nicely illustrates the value of the Triadic Framework because it shows how the integration of nature, communities, and belief systems with self-concepts results in a robust approach for sustainability. Each element of the triad is tightly integrated with the others, and thus protecting mature forests simultaneously supports one’s community and reaffirms one’s spiritual beliefs. Further, because each element of the triad is also highly self-relevant (e.g., importance of Hindu beliefs, personal benefits from protecting the forests, feeling greater belongingness from being a part of a community committed to protecting sacred groves), the motivation to maintain sustainable practices is heightened. AERF brings new knowledge and opportunities to these communities (e.g., a deeper appreciation of how the sacred groves support a range of species who rely on these forests for their survival, ways to bring medicinal products to markets that generate income in sustainable ways) while ensuring that local community members’ values and benefits are at the forefront of consideration.

4. Leveraging the Triadic Framework for Everyday Sustainability

The AERF example in the Western Ghats of India illustrates many features of the Triadic Framework well. However, we wish to extend an invitation to readers to apply this approach to everyday sustainability efforts. We believe there are many conservation opportunities where nature, communities, and belief systems can be integrated with each other and into self-concepts to produce sustainable pro-environmental outcomes. For example, people can face challenges with invasive species overrunning neighborhoods, forests, and parks. Additionally, many communities wrestle with keeping streams clear of pollution and chemical runoffs. In addition, supporting local farmers’ sustainable agriculture improves local communities and the quality of the foods we eat. Sometimes, indigenous groups work together to reclaim native homelands to retain cultural identities and practices. Further, local youth can develop plans for community gardens to establish spaces for neighbors to grow their own food. These are all common situations where we believe the Triadic Framework can help develop more sustainable solutions. By explicitly adopting this framework, multiple mutually reinforcing elements can be identified and integrated into a system of interrelations that are enmeshed with people’s self-concepts.

When considering everyday opportunities like those described in the previous paragraph, identifying the nature element is usually easy (e.g., preserving native plants being overrun by invasive species). However, sometimes identifying and integrating the full triad of elements (i.e., communities and belief systems) in these efforts may be less obvious. For example, consider a situation where conservationists wish to eliminate invasive honeysuckle (Lonicera spp.) choking out native redbud trees (Cercis siliquastrum) in local parks. A common conservation approach might be to produce pamphlets describing the importance of native species for the local ecosystem and distributing them to households for educational purposes—this approach tries to increase people’s concern about nature. However, the Triadic Framework would encourage conservationists to identify additional elements that can be leveraged in this effort. For example, local high school science students could be enlisted (community) to adopt redbud conservation as a focus of their science education (belief systems) curriculum thereby building community–belief system connections. These students might volunteer to rehabilitate local parks (e.g., remove invasive honeysuckle and plant redbud saplings) on spring weekends, becoming “redbud guardians” for the town (deepening integration between nature and their self-concepts). These students could encourage the town (another community) to adopt the redbud as its official tree (deepening nature–community overlap), which could lead to establishing a “We love our redbuds” festival for the town each spring to coincide with the emergence of the trees’ magnificent purple flowers, building a sense of shared community values (community–belief system overlap) and serving people’s belongingness needs by having local residents attend the festival (further integrating community with residents’ self-concepts). In sum, the Triadic Framework encourages conservationists to identify more ways to build interconnecting relations among elements that support nature, mutually reinforce each other, and integrate with people’s self-concepts.

5. Conclusions

We presented the Triadic Framework to explore how nature, communities, and belief systems can be interconnected and enmeshed with the self-concept to foster sustainability. This approach builds on established field conservation work and leverages literatures from psychology and biology, which include vetted pro-environmental methods and approaches such as nature connectedness and community-based conservation. Identifying nature, communities, and belief systems as important elements of our model underscores their interconnections, and incorporating these elements with self-concepts amplifies people’s personal motivations and commitment to conservation. We believe the Triadic Framework offers several important contributions to improving sustainability efforts, which in turn, further highlights its contribution value.

First, communities and belief systems often receive less attention than nature in pro-environmental efforts because people are understandably focused on preserving nature, and the Triadic Framework encourages an active consideration of these sometimes neglected elements. Although communities are important for efforts such as community-based conservation, our framework anticipates greater pro-environmental success when those communities are not only concerned with nature but also endorse belief systems that support sustainability (e.g., shared cultural values, affirming science). Further, to the extent that self-concepts become more central in conservation efforts (e.g., participating in conservation activities enhances people’s feelings of belongingness), people should be highly motivated to sustain conservation because of greater enmeshment between communities and sense of self. Similarly, fostering greater overlap between the self-concept and belief systems that value nature should enhance conservation motivations. Thus, our framework identifies new roles for the self-concept involving integration with communities and with belief systems (and not just nature connectedness).

In addition, we welcome future work to fully evaluate the framework, test its features, and to consider novel questions it generates. The framework certainly has limits that future research should examine, such as whether “place” should be another element included in the model or whether all forms of overlap between self-concepts and elements are equally weighted in importance. The framework also identifies new questions for conservation scholars to consider. For example, are communities critical to sustainability because of their social capital or the belongingness they provide? Additionally, might personality differences qualify the relations described herein (e.g., perhaps extraverts value overlap between communities and self-concepts to a greater degree than do introverts)? Thus, although the importance of self-concept integration is likely important for all people, the elements that matter most may differ in scale and across people in systematic and meaningful ways. By emphasizing the importance of self-concept integration as a primary motivator of behavior, the Triadic Framework allows conservationists to identify new questions and to develop new approaches to improve sustainability.

Finally, because of the importance of cooperation in solving many sustainability challenges (e.g., global warming, food web collapses), appreciating the interrelations between communities and belief systems seems especially important. Local people are not only important for enacting conservation behaviors, but they often have valuable local knowledge that offers unique insights for sustainability. Thus, explicitly acknowledging and leveraging belief systems is not only important for engineering better pro-environmental solutions, but honoring belief systems is important for combatting group stereotypes that harms intergroup cooperation. In sum, sustained conservation action is dependent on integrating nature, communities, and belief systems with people’s self-concepts, and we believe the Triadic Framework not only can offer valuable approaches for improving the natural environment but for building authentic, healthy personal relationships among those needed for positive conservation action.