Abstract

Having experienced the turbulent change in corporate value rankings over the past 20 years, companies are paying attention to their reorganization to quickly recognize changes and proactively adapt to these changes for survival. This study examines the relationships and intervening ambidexterity mechanisms between CEOs’ leadership style and employees’ learning agility. Using multilevel regression, we analyze hypotheses on a sample of 102 participating CEOs and 236 employees. Results reveal that the ambidextrous organization, which pursues the current organizational development while constantly adapting to changing environments, plays a role as a partial mediator between transformational leadership and members’ learning agility. These results explain that to increase the organization’s agility, a systematic organizational structure system that stimulates members’ motives and simultaneously pursues utilization and exploration must be established through clear goals and appropriate stimuli even in an uncertain environment. Our finding contributes to an understanding of how the CEO’s leadership style affects employees’ learning agility in ventures and to what extent the contextual ambidextrous structure influences the relationship.

1. Introduction

What are the competencies that companies need to survive in an era of increasing uncertainty? According to Darwin (1964) [1], “The surviving species are not the strongest or the smartest, but the ones that adapt best to change.” Companies with 100 years of history have experienced turbulent changes in corporate value rankings in the last 20 years [2]; hence, they need to accurately recognize, respond, and adapt to changes for survival [3]. According to the CB insight [4], the pace at which organizations learn and change is also a critical factor. For example, since the establishment of the first unicorn company “Bloom Energy” in 2009, it took 20 months for another unicorn company to be born. However, since 2018, one unicorn company has been born every three days. In other words, we faced a situation where going beyond existing organizational learning capabilities and paying attention to how agile these capabilities could be mounted on the members are necessary. Previous studies have demonstrated that the more dynamic the society is, the more critical is the learning competencies of the members to create results; moreover, these competencies are maximized when the members of the organization sensitively respond to the environment and accommodate change [5,6,7]. Now, organizations must increase their learning agility for survival and pay attention to the needed leadership style and innovation strategies. In particular, CEO leadership is found to be very closely related to improving learning capabilities in the work environment [8]; among others, transformative leadership styles have a powerful influence on organizational learning [9].

This is because transformational leadership itself has an intuitive appeal and is interested in the growth of members and motivates members so that they can achieve higher-than-expected results [10]. Strategic management of organizational resources performed by these leaders also attracts attention as an element that makes organizational agility possible [11]. Therefore, this present study aims to further illustrate how transformative leadership affects the organizational members’ agility. Learning agility is defined as the willingness and ability to learn new competencies for performing tasks in difficult and new environments [12]. Fast learning and acquisition of new skills are essential in a changing environment, and successful people, in contrast to failures, have shown high learning agility [13]. Moreover, how organizational resources are strategically managed in relation to organizational agility is seen as a practical factor [14]. For decades, scholars have proposed theories for improving existing businesses, adopting innovations, or adapting to changing environments for organizational survival [15,16,17]. They concluded that the improvement and adaptation would not be possible without corporate agility [3]. Solutions such as the dynamic capabilities approach or a cross-functional team have been proposed to improve agility [18]. However, obtaining poor results, O’Reilly and Tushman (2008) [3] confirmed that they took an ambidextrous organizational structure, paying attention to the surviving companies. Indeed, ambivalence is considered to positively influence organizational agility and performance [19]. In addition, companies cannot neglect to cope with external changes while strengthening their internal competencies, and vice versa. Therefore, the ambidextrous organization, which uses existing resources and strengthens exploratory capabilities for new resources and methods, is recognized as a function that can support organizational agility [20,21]. For a modern company to grow in the long term, it needs a dynamic ability to meet the requirements for future business development activities while successfully conducting its current activities. Numerous solutions have been suggested in order to motivate companies to improve their agility by using a dynamic capabilities approach or cross-functional units [18]. However, achieving ambidexterity for agility is not easy. Because of its competing goals of efficiency and innovation, exploitation and exploration are often described as paradoxical [22]. Existing research proposes leadership behaviors and intra-firm contexts and structures are vital antecedents to ambidexterity [23,24,25]. Han et al., 2021 [26] indicated a leader’s dialectical thinking facilitates team-level ambidexterity, which in turn affects employee performance. Research into the role of paradoxical cognition [24] and best ambivalence such as behavioral integration [27] is beginning to emerge. The role of leaders in work teams throughout the company is much less understood [28]. Therefore, this study examines the relationship between leadership and ambidexterity in dynamic internal contexts. The type of leadership considered in this study is transformational leadership as a set of behaviors and attributes [29,30]. Transformational leadership is charismatic, inspiring, intellectually stimulating, and individually caring [29,30]. Transformational leaders are more likely to be effective in dynamic environments and to implement learning ability [31]. Thus, this study focuses on the mediating effect of ambidextrous structure between transformational leadership and learning agility in an era of high uncertainty and volatility, such as in modern society.

Many large corporations in South Korea such as Samsung, LG, and Naver support ambidextrous structures like corporate venture unit or corporate venture capital to overcome the organization’s inertia and pursue creative innovations [32]. In particular, we are conducting an empirical survey on the leadership and members’ learning agility of small- and medium-sized enterprises whose organizational responses to environmental changes are not well known compared with large corporations. Resource allocation must be preceded to implement an ambidextrous organizational structure [33]. It is meaningful to verify whether SMEs (vs. large companies) with much smaller resources are pursuing an ambidextrous innovation structure and promoting organizational agility improvement through this. Additionally, from the perspective of leadership and learning organizations that have been studied so far, we can measure the organizational agility and capacity to interact with dynamic environments and respond flexibly. Moreover, we can explore the role of leaders to improve them.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Review

2.1.1. Transformational Leadership

Traditional leadership theories focus on how the leader influences subordinates to achieve a given goal, whereas transformational leadership focuses on how the leader inspires organizational members to achieve success beyond their goals [29]. In other words, rather than maintaining the status quo, transformational leadership leads the organizational change, overcomes the difficulties caused by external changes, and pursues more than the expected performance.

Moreover, transformational leadership is the process of transforming individuals by exerting a long-term impact on the values, ethics, and codes of conduct of the organization’s members, rather than wielding or exercising power; it is emphasized as a concept that includes things [34]. This is a concept that contrasts with transactional leadership. In theory, transformational leadership is assumed to be more effective than transactional leadership in situations of high uncertainty because it provides direction and confidence to the members of the organization [35,36,37].

With the recent rapid technological advancement and environmental changes, the organization has paid attention to the leadership style with diverse experiences and flexibility [38]. The usefulness of transformational leadership in enhancing organizational satisfaction, commitment, and effectiveness has been demonstrated [31]. Moreover, the understanding of the transformational leadership dynamics has also increased. A leader with transformational leadership suggests a vision, arouses the trust of subordinates, sets a clear goal, sets an example, and leads the way to increase the performance and satisfaction of the organization and its members; he/she does this through careful consideration and appropriate stimulation to the needs of subordinates [39]. In particular, transformational leadership is the most appropriate leadership from the perspective of the learning organization [40].

Research on transformational leadership, in particular, on leadership and learning outcomes, has been relatively active, and many studies have demonstrated the positive effect of leadership on organizational learning practices [41,42,43,44]. To create successful outcomes despite a dynamically changing knowledge-based creative society, organizations must learn the innovation capabilities of their members. Moreover, these capabilities are maximized when members respond sensitively to the environment and actively embrace change [5,6,7]. Interventionary studies involving animals or humans, and other studies that require ethical approval, must list the authority that provided approval and the corresponding ethical approval code.

2.1.2. Organization’s Ambidextrous Structure

The concept of an ambidextrous organizational structure was first theorized by Duncan (1976) [45] in the 1970s when it dynamically changed from a static form to the environment faced by an organization. Until recently, research on ambidextrous organization has been mostly conducted theoretically and empirically [15,23]. Scholars have demonstrated the following factors that determine the survival and performance of an organization: manufacturing efficiency and flexibility [15], differentiation and cost-leadership positioning [46], and global integration and regional response [47]. These is an organizational ability to pursue two different concepts at the same time [47,48,49]. As a result, an ambidextrous organization is an organization that can explore new opportunities and environment simultaneously. It can also pursue the development of current organizational processes while constantly adapting to the changing environment [47]. Meanwhile, exploration means exploring and capturing new external technologies to launch new products and advance into new markets, whereas exploitation means an activity that gradually improves existing products by using technical resources owned by a company [17]. The exploration includes searching, taking risk, discovering, and innovating to prepare the field for the work to be used. Meanwhile, exploitation includes the organization’s ability to innovate, produce, optimize, and increase business execution [23]. Thus, the ambidextrous organizational structure improves the innovative ideas for the two competencies of a company, products, services, production processes, and management capabilities. It also has an impact on improving the current operational speed, reliability, and cost aspects.

Maintaining the balance of exploitation and exploration has been successful for SMEs, large corporations [50], and public institutions [51]. However, making an organization “ambidextrous” is not an easy task possibly because of the professionalism of the organization and its members. They obtained the most experience and knowledge; hence, they know how to be effective in the current situation. That is, by organizational inertia, they may find that pursuing “doing things better” (exploitation) is more rational and less resistant than pursuing “doing better things” (exploration) [52]. However, they believe that exploration is necessary for adapting to a changing environment and for survival in the future [53,54]. This “ambidexterity dilemma” has two perspectives: differentiation view and integration view. From the differentiation view, exploratory learning and exploitative learning are incompatible because they compete for the same resource [55]. Meanwhile, from an integration view, the two approaches are complementary [23]. Therefore, from a differentiation viewpoint, we propose a “sequential ambidexterity” in the process of changing from one “state” to another or approaching the structural ambidexterity that can make decisions by separating the search and utilization into different departments. Both literature streams provide insights into the concepts and benefits of exploration and exploitation; however, how ambidexterity can be leveraged in organizations is lacking [54,55].

Therefore, recent studies have discussed ambidexterity in terms of indivisible capacity [15]. Organizational mechanisms require ambidexterity at the individual level. Moreover, ambidexterity is a critical factor in the usage of manipulative mechanisms in ambidextrous individuals [15].

This is called contextual ambidexterity from an integrative perspective. It refers to the behavioral competence that simultaneously demonstrates coordination and adaptation across the entire business unit [23]. In other words, contextual ambidexterity refers to the interaction of exploration and usage in a contextual work environment. By understanding this, the ambidexterity dilemma can be solved. Furthermore, it can be achieved through the participation of employees, and under what circumstances an organizational intervention can be successful is confirmed [23,56,57,58]. In particlular, contextual ambidexterity has been pursued simulatiously as a source of market competitiveness [59]. Therefore, based on contextual ambidextrous theory, the current study examines how the competencies of members are improved by comparing ambidextrous structure.

To achieve a positive effect of the ambidextrous organizational structure on the performance, members of the organization must exhibit an active will to change and adapt the organization’s changes as well. The ambidextrous structure is closely related to the agility of the organization, especially the market capitalization and the organization’s operational agility [60]. This is because the former responds to changes by continuously monitoring and rapidly improving products or services to meet the needs of current consumers, whereas the latter responds successfully and quickly to changes in the overall market or demand. In an ambidextrous organizational structure, exploratory innovation contributes to developing new models of service, sales, and manufacturing. Such disruptive innovation is an essential element of rapid organizational response to market changes and opportunities [61]. Additionally, utilitarian innovation may lead to companies’ reorganization to rapidly respond to emerging crises such as natural disasters and supply chain changes [62]. In other words, to increase the flexibility to cope with the complexity and diversity of the current market, an ambidextrous organizational structure is formed, contributing to the improvement of the entire organization’s agility level.

Recently, most large corporations have pursued the establishment of exploratory organizations to discover new businesses and cultivate talents, moving away from the current form of use-oriented organization that only pursues efficiency [63]. Representative examples include corporate venturing and corporate venture capital establishment. SMEs, like large companies, are under competitive pressure to pursue utilization and exploration jointly. However, compared to large corporations, SMEs indeed lack not only slack resources, but also hierarchical systems that manage contradictory knowledge systems. For example, large corporations can create separate business units structurally and manage them by focusing on the usage for each department. However, in SMEs and ventures, the willingness and ability of a leader or TMT (top management team) are critical to achieve the organizational structure because mechanisms to promote this are lacking. This is because the hierarchical level is small, so top managers will likely perform strategic and operational roles [27]. Therefore, as O’Reilly & Tushman (2013) [18] suggested, an ambidextrous organizational structure will be promoted by senior management or a leader to promote organizational change.

2.1.3. Learning Agility

The organization’s sustainable growth and the discovery and development of future key talents are recognized as the most essential priority for most companies [64,65]. Until now, the perspective of looking at these core talents has been developed in the form of selecting and fostering high performance based on work experience and achievements. However, as it turns out, in today’s uncertain environment, high performers in the past do not guarantee success and growth as expected in the future [12,66,67]. Due to its potential, “learning agility” is attracting attention as an essential core competency [68,69,70,71].

According to previous studies, learning aptitude is the will and ability to learn from experience; it refers to the ability to learn quickly and flexibly change thoughts and actions even in new environments [52,64]. Lombardo and Eichinger (2000) [12] established the concept of learning agility. Moreover, people with excellent learning agility learn new tasks quickly, prefer change rather than a stagnant state, and tend to challenge limitations [49]. People with high learning agility are more likely to grow into future leaders or experts. That is, if more members of the organization have high learning agility, the organization will more likely achieve sustainable growth and survival [72].

However, studies to date have not provided insights into why certain individuals or organizations have a high learning rate. Likewise, explanation about which people have a high understanding of a specific situation, flexibly switch ideas and perspectives, and connect resources according to the situation is lacking [73]. In previous studies, personal and situational factors that influence individual learning from experience were investigated; hence, how they affect learning agility, intelligence, goal orientation, and personality corresponding to personal factors was also explored [68,74]. Meanwhile, access to role models and complexity, opportunities for reflection, and new experiences such as change are also examined. Situational elements of exposure to novel experiences have promoted learning agility [75]. This suggests the importance to present a role model or leader that can stimulate learning agility in the organization. Moreover, an organizational structure that can enhance individual competencies must be provided by creating challenging experiences for the organization’s members.

Putting together the studies on learning agility, we can see three things in common: First, learning agility plays an important role when meeting new jobs, etc. through “new and new situations or tasks” [76]. Second, some competencies acquired through previous experiences have been discarded, updated, and added to acquire new competencies to make “the ability to connect experiences” possible [77]. Third, in terms of “flexibility and speed,” the higher the learning agility, the more flexible the learning contents between situations can be applied and the faster is the learning from experience [78].

2.2. Hypothesis Setting and Research Model

2.2.1. Relationship between Transformational Leadership and Learning Agility

Research on transformational leadership has focused on the effects on members’ motivation and performance [79]. Results of the interviews with successful leaders reveal that their constant success factor is learning through challenging experiences [80]. In contrast, in the case of leaders who fail in the middle, they have tremendous enthusiasm and commitment to the organization, but they lack the flexibility to respond to new environmental changes [80]. In other words, in a more complex and globalized environment, leaders must have the ability to respond quickly even in highly paradoxical situations, and the talents chosen by the organization should also consider the ability to learn and adapt to new roles, not just achievements [12]. These studies draw attention to transformational leadership, which improves organizational performance by understanding the organization’s current situation and target value and by allowing members to be motivated by high-level desires rather than mere rewards [81]. The transformational leadership that shares a vision with members and motivates them through appropriate challenging stimuli brings changes in their own beliefs and values, thereby arousing a desire to learn and grow independently. In other words, in a situation where the leader is uncertain, sharing the vision and clear goals, meticulous consideration and encouragement, and appropriate stimulus motivate members to grow, think flexibly, and urge behavioral change by reflecting on their work.

In particular, venture companies need members who can acquire information and knowledge about the rapidly changing new technologies through learning activities and use them in uncertain work situations [82]. Therefore, the leaders of venture companies will try increasing the learning agility of the organization through the sharing of vision and motivation for change.

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

CEO’s transformational leadership positively affects learning agility.

2.2.2. The Relationship between Transformational Leadership, Ambidextrous Organization, and Learning Agility

Scholars in the field of organization have recognized the importance of balancing contradictory strains and have begun to focus the paradoxical thinking in dynamic environments [22,83,84]. In addition, there is a growing awareness of the role of system and processes present in a given context to achieve the desired balance between different demands. In this study, we propose the concept of contextual ambidexterity, which means behavioral capacity to simultaneously demonstrate alignment and adaptability across an entire firm [23]. Ghosha and Bartelett’s (1994) [85] study suggests contextual ambidexterity emerges when leaders develop a supportive organization context. In accordance with these perspectives, a company’s performance is not achieved chiefly through charismatic leadership, nor through a typical organizational structure. It can be achieved by a well-organized system and process [23]. Transformational leadership can positively influence the system and process in addition to the results of organizational learning [86]. From a resources perspective, transformational leadership produces a supportive environment for employees, which fosters resource accumulation while reducing work conflict and stress [87,88]. Intellectual stimulation and individual consideration, which are sub-factors of transformational leadership, can promote exploration capabilities of members, and ideal influence and inspirational motivation can promote exploration [89].

According to previous studies, transformational leadership affects the duality of the organization [68], and the ambidextrous organization is an organization capable of responding to the contradictory nature of exploration and usage of progressive and disruptive innovation [25]. Muhammad et al. (2021) [90] also examined the significant positive relationship between shared vision and radical innovation with mediation of contextual ambidexterity.

Ambidextrous people who seek external opportunity and internal organizational efficiency and naturally include the concept of agility [59]. Zain et al. (2005) [91] identified how organizations aim for agility, that is, “how to quickly assemble technology, staff and management into a telecommunications infrastructure to respond to changing consumer demands in a continuous and unexpected market environment”(p. 831). Looking at an empirical study on an ambidextrous organization’s agility, we found that an ambidextrous organization can quickly respond to market changes while maintaining the satisfaction of existing consumers [54] and knowing how satisfied are they with the products, which can be evaluated [33]. An ambidextrous organization’s technical and organizational flexibility or adaptation to change is emerging as a competitive advantage of organizational agility [18,19].

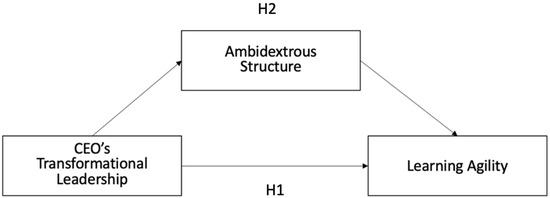

Therefore, the leader makes efforts at the organizational level to increase its members’ agility and thus achieve a competitive advantage in a rapidly changing environment. In particular, a transformative leader who practices challenging experiences and motivation for change stimulates members to secure organizational agility. Following to Figure 1, ambidextrous organizational structure will play a mediating effect in realizing the leader’s vision.

Figure 1.

Research Model.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

The organization’s ambidextrous structure plays a mediating role in the relationship between the CEO’s transformational leadership and the members’ learning agility.

2.3. Sample and Method

2.3.1. Sample

In this study, we investigated IT venture companies located in the Seoul and Gyeonggi. The study period was from 6 March to 23 March 2019, for CEOs and employees of venture companies. This study’s sample was considered a multilevel model because the relationship between the CEO and employee has hierarchical characteristics. The survey was conducted offline, and 105 of the 110 people distributed to representatives and executives responded. Among them, the empirical analysis was conducted with the results of 102 people excluding 3 people with uncertain answers. In addition, the employees analyzed a questionnaire targeting a total of 236 employees of the same company of the CEO. To analyze the relationship, this study uses the R 3.5.0 program.

The general characteristic of this study’s sample was as follows to Table 1; in the case of CEO, 85.29% were males and 14.71% were females. Moreover, the distribution in terms of founding was 53.92% were founders and co-founders, whereas 46.08% were executives who were not the founders. For the positions, 58.82% of the respondents were the representative director; 35.3%, executive/executive director; and 5.88%, vice president. Additionally, for the number of years of service, 33.34% of the respondents worked for the company for 6–10 years; 27.45%, more than 15 years; 16.67%, less than 3 years; 11.76%, 11–15 years; and 10.78%, 3–5 years. In the case of employees, 75% were men and 25% were women. The distribution of the managerial position was as follows: managers (32.20%), deputy managers (16.53%), and managers (15.25%), surrogate (13.14%), and others (22.88%). The years of service are less than 3 years (30.08%), 3–5 years (22.03%), 6–10 years (20.34%), 11–15 years (11.86%), and over 15 years (15.69%).

Table 1.

Characterization of the study.

2.3.2. Methodology

In organizational studies, the variables at the organizational level are affected by the individual members because of the structural characteristics [92]. Research on venture companies also needs to be considered from a multi-layered perspective so that the interaction effect of the variables at the organizational and individual levels can be confirmed. Ecological fallacy is a phenomenon in which organizational members are ignored when researching venture companies through multi-level analysis. Meanwhile, atomic fallacy generalizes and theorizes phenomena and relationships at the individual and organizational levels [93].

However, most studies on the relationship between variables at the individual level have been conducted in entrepreneurial research so far [94]. Therefore, the hypothesis of this study is tested according to the premise that the organization contains individuals and groups and the attribute itself is multilevel [95], that is, an individual member of the organization inherent in the group called venture business. A multilevel model was used.

2.3.3. Measures

We tested both the direct and indirect effects between CEOs’ transformational leadership and employees’ learning agility. This study aimed to verify the multilevel antecedents affecting employee’s learning agility, key variables, and methodology described below.

Transformational leadership. We evaluated the CEOs’ transformational leadership using a 20-item scale from Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire(MLQ) developed by Bass and Avolio (1997) [96]. Transformational leaders motivate followers to achieve performance beyond expectations by transforming followers’ attitudes, beliefs, and values instead of simply gaining compliance [29,97,98]. Bass (1985) [29] identified many subdimensions of transformational leadership, including charisma (which was later re-named idealized influence), inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration. Moreover, the MLQ was widely used and regarded as a well-validated measure of transformational leadership [99]. Its construct validity has recently been demonstrated using confirmatory factor analysis (cf. Avolio et al., 1999 [100]). The sample items consistent with our conceptualization of transformational leadership include charisma (e.g., “My CEO goes beyond self-interest for the good of the group), inspirational motivation (e.g., “My CEO is very optimistic about the future”), intellectual stimulation (e.g., “My CEO is very optimistic about the future”), and individual consideration (e.g., “My CEO regards individual employees as personalities with different needs, abilities, and passions than others”).

Ambidextrous structure. In terms of corporate innovation, exploration means discovering new capabilities rather than existing capabilities and exploring and developing new technologies different from existing ones. Meanwhile, exploitation refers to innovation and improvements based on existing technology [101]. In this study, four items of exploration activities, such as the discovery of next-generation products/new customers, were adopted from He and Wong (2004) [101]. These items have been used by many subsequent researchers and are recognized for their conceptual validity and utilization of quality, delivery, and cost improvement of current products. Moreover, four activities were used.

Learning Agility. It is the will and ability to learn from experience and refers to the ability to learn quickly and flexibly change thoughts and actions even in the new or first-time environments [12,76]. In this study, we adopted Im et al.’s (2017) [102] measurement tools, which were developed by restructuring the preceding ones. Im et al. (2017) [102] analyzed the measurement tools of Lombardo and Eicher (2000) [12] (i.e., CHOICE model), Bedford (2011) [66], and Spritzer et al. (1997) [103] to define the concept of sub-dimension, develop items, and confirm the validity and reliability. Thus, in this study, learning agility was analyzed using 22 items related to the following five areas: self-awareness, growth-orientation, flexible thinking, reflexive behavior seeking, and behavioral change.

3. Results

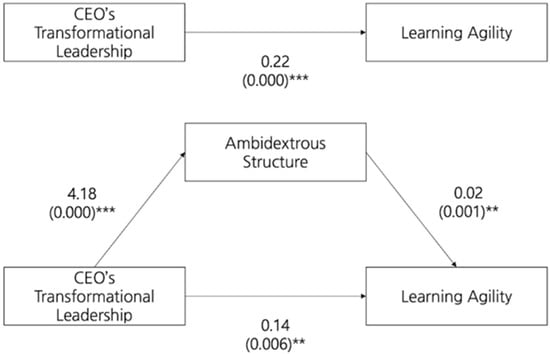

To confirm whether the ambidextrous organization has a mediating effect on the relationship between the leader’s transformational leadership and the employees’ learning agility, we must verify first whether the independent variable has a significant influence on the dependent variable (See Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Path model result. ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001.

According to Table 2, H1 is confirmed: the direct effect of the CEO’s transformational leadership on learning agility is statistically significant (β = 0.22, p = 0.000, t = 5.35). Therefore, in testing H2 (i.e., the ambidextrous structure has a mediating effect on the relationship between the CEO’s transformational leadership and the learning agility), this study confirms the direct and statistically significant effect of transformational leadership on the ambidextrous structure in step 2 (β = 4.18, p = 0.0.000, t = 11.29). In step 3, we analyzed the influence of the CEOs’ transformational leadership as an independent variable and ambidextrous structure as a parameter on learning agility. Results revealed that the direct effect of ambidextrous structure on learning agility is significant (β = 0.02, p = 0.001). Similarly, the direct effect of ambidextrous structure on transformational leadership and on learning agility is also significant (β = 0.14) at the 0.05 level. The results indicated that the ambidextrous structure does not fully mediate the relationship between the CEOs’ transformational leadership and the learning agility variables. It also implies the partial mediating effect of ambidextrous structure. Subsequently, we analyzed the effect of the independent and dependent variables in step 1 and the magnitude of the effect in step 3. Results reveal that the direct effect of the CEO’s transformational leadership on agility in step 1 (β = 0.22) is more pronounced than that on learning agility in step 3 (β = 0.14). Therefore, the ambidextrous structure variable partially mediates the relationship between transformational leadership and learning agility.

Table 2.

Complete results of the mediation model.

A causal mediation analysis was performed to separate and confirm the total effect of mediation analysis into direct and indirect effect. Indirect effects are passed through the mediator. The mediation process is designed to perform CMA under the assumption of sequential override possibility. It reports the average causal mediation effect (ACME), average direct effect (ADE), and total effect. The average mediating, direct, and total effects are 0.08 (p = 0.008), 0.14 (p = 0.004), and 0.22 (p = 0.000), respectively, confirming the presence of a mediating effect (See Table 3).

Table 3.

Mediation Analysis.

4. Discussion

We examined multilevel antecedents to employees’ learning agility in a venture context. The results showed that CEOs’ transformational leadership style is positively related to employees’ learning agility. We also found that ambidextrous structure mediates the relationship between CEOs’ transformational leadership and employees’ learning agility.

As expected, the CEOs’ leadership capacity influences employees’ learning behavior, such as learning agility. According to Vroom’s (1964) [104] expectancy theory, transformational CEOs intrinsically motivate their employees to exhibit learning agility by using expectancy as a motivational force. Furthermore, transformational leadership ultimately shifts the employees’ existing values to the new vision suggested by their leaders. In other words, employees tend to internalize the value of their transformational CEO’s direction into their personal value system, which can be transformed through the value congruence process between leaders and followers [105]. Following Avolio and Bass (1988) [106], we believe that the transformational leadership style is the most appropriate leadership for organizational learning aspect rather than other leadership styles. Thus, this study supports and extends the literature on leadership and organizational learning [41,107] by suggesting that a transformational CEO influences the learning agility of employees.

This research also sheds light on the role of a firm’s ambidextrous structure. Our results reveal that a CEO’s transformational leadership is related to a firm-level ambidextrous structure. Moreover, our finding suggests that an ambidextrous structure affects employees’ learning agility under transformational leaders. Namely, the ambidextrous structure established by a CEO’s transformational leadership promotes employee’s learning agility, which might have a theoretical reason. Raisch et al. (2009) [15] posited that organization mechanisms on ambidexterity lead to a change in individual behaviors. Based on contextual ambidexterity, which is defined as “the behavioral capacity to simultaneously demonstrate alignment and adaptability across an entire business unit” [47], the contextual ambidextrous structure enables employees to make their own judgments about how to divide their time and activity between conflicting demands. Brix (2020) [108] examined which ambidextrous organizational mechanism can enhance the sustainable innovation capacity of its members in the corporate learning view. As such, ambidextrous structures affect employee behavior, but to succeed, resource allocation, leadership style, incentive structure, etc., must be considered [58,109,110].

The present study examines the changes in the sustainable innovation capacity of members through ambidextrous structure, in particular, the effect on learning agility. Learning agility is the willingness and ability to learn from experience [111] and is a key competency for future sustainable growth potential [68,69,70,71]. This study shows that the ambidextrous organizational structure increases both the innovation capacity and the learning agility of an individual who wants to learn and apply it quickly and flexibly. In other words, the company’s efforts to pursue the interaction between exploration and exploitation indeed affect the behavior of organizational members to follow it. Additionally, the resource allocation problem and reward system were pointed out in the ambidextrous structure’s success; however, small venture companies can be sufficiently changed according to appropriate leadership such as transformational leadership. This finding may imply that transactional leadership in a venture might help improve organization speed, and ambidexterity structure would be an effective method.

Our findings also suggest that entrepreneurs could recognize the important outcome of a CEO’s leadership such as establishing a firm-level ambidextrous structure. According to motivation theory [112], firm-level culture may lead to a situational constraint, which will be supportive in improving advantageous performance. Once an ambidextrous structure is installed in a company, CEOs might be able to facilitate the employees’ desirable behaviors to accomplish organizational goals. This effort of creating a flexible ambidextrous structure would potentially lead to a strong organizational learning culture.

Limitations and Future Research

Additionally, this study is a survey of small- and medium-sized venture companies in Korea. It reveals that the specificity of domestic companies can affect the research results. Finally, in this study, the causal relationship was revealed only in transformational leadership among the leadership styles. Therefore, a more rigorous relationship verification in connection with various leadership styles is needed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.J.L.; Project administration, G.K. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Darwin, C. On the Origin of Species: A Facsimile of the First Edition; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Jongang Ilbo. Available online: https://news.joins.com/article/21994422 (accessed on 9 October 2017).

- O’Reilly, C.A., III; Tushman, M.L. Ambidexterity as a dynamic capability: Resolving the innovator’s dilemma. Res. Organ. Behav. 2008, 28, 185–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CB Insight. The Complete List of Unicorn Companies; CB Insight: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Shea, G.P.; Solomon, C.A. Leading Successful Change, Revised and Updated Edition: 8 Keys to Making Change Work; Wharton Digital Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, S.W.; Whisler, T.L. The innovative organization: A selective view of current theory and research. J. Bus. 1967, 40, 462–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, M.S.; Van den Ven, A.H.; Dooley, K.; Holmes, M.E. Organizational Change and Innovation Processes: Theory and Methods for Research; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, L. Leadership and organizational learning culture: A systematic literature review. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2019, 43, 76–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L. The impact of servant leadership and transformational leadership on learning organization: A comparative analysis. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilley, J.; Eggland, S.; Gilley, A.M.; Maycunich, A. Principles of Human Resource Development; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hellriegel, D.; Slocum, J.W. Management, 6th ed.; Addison Wesley: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Lombardo, M.; Eichinger, R. High potentials as high leaders. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2000, 39, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, M.; Eichinger, R. Preventing Derailment: What to Do before It’s too Late; Center for Creative Leadership: Greensboro, NC, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bharadwaj, A.S. A Resource-Based Perspective on Information Technology Capability and Firm Performance: An Empirical Investigation. MIS Q. 2000, 26, 169–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raisch, S.; Birkinshaw, J.; Probst, G.; Tushman, M.L. Organizational ambidexterity: Balancing exploitation and exploration for sustained performance. Organ. Sci. 2009, 20, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Del Giudice, M.; Peruta, M.R.D. The impact of IT-based knowledge management systems on internal venturing and innovation: A structural equation modeling approach to corporate performance. J. Knowl. Manag. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzi, G.; Zollo, L.; Boccardi, A.; Ciappei, C. Additive manufacturing in SMEs: Empirical evidences from Italy. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Manag. 2018, 15, 1850007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, C.A., III; Tushman, M.L. Organizational ambidexterity: Past, present, and future. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 27, 324–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vrontis, D.; Thrassou, A.; Santoro, G.; Papa, A. Ambidexterity, external knowledge and performance in knowledge-intensive firms. J. Technol. Transf. 2017, 42, 374–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, O.K.; Lim, K.H.; Sambamurthy, V.; Wei, K.K. IT-enabled organizational agility and firms’ sustainable competitive advantage. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Eighth International Conference Information Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 9–12 December 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Subramani, M. How do suppliers benefit from information technology use in supply chain relationships? MIS Q. 2004, 28, 45–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lewis, M.W. Exploring paradox: Toward a more comprehensive guide. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 760–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, C.B.; Birkinshaw, J. The antecedents, consequences, and mediating role of organizational ambidexterity. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 209–226. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, W.K.; Tushman, M.L. Managing strategic contradictions: A top management model for managing innovation streams. Organ. Sci. 2005, 16, 522–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tushman, M.L.; O’Reilly, C.A., III. Ambidextrous organizations: Managing evolutionary and revolutionary change. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1996, 38, 8–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Han, G.H.; Bai, Y.; Peng, G. Creating team ambidexterity: The effects of leader dialectical thinking and collective team identification. Eur. Manag. J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubatkin, M.H.; Simsek, Z.; Ling, Y.; Veiga, J.F. Ambidexterity and performance in small-to medium-sized firms: The pivotal role of top management team behavioral integration. J. Manag. 2006, 32, 646–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nemanich, L.A.; Vera, D. Transformational leadership and ambidexterity in the context of an acquisition. Leadersh. Q. 2009, 20, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M. Leadership & Performance Beyond Expectations; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B.M. Transformational Leadership: Industrial, Military, and Educational Impact; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Vera, D.; Crossan, M. Strategic leadership and organizational learning. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2004, 29, 222–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.H. Korea Allows Large Firms to Hold Venture Capital Units. 2020. Available online: http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20200730000706 (accessed on 19 July 2021).

- Rialti, R.; Marzi, G.; Silic, M.; Ciappei, C. Ambidextrous organization and agility in big data era. Bus. Process. Manag. J. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burns, J.M. Leadership; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B.M.; Avolio, B.J. Transformational Leadership Development: Manual for the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire; Consulting Psychologist Press: Palo Atto, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, J.J.P.; Vera, D.; Crossan, M. Strategic leadership for exploration and exploitation: The moderating role of environmental dynamism. Leadersh. Q. 2009, 20, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamir, B.; House, R.J.; Arthur, M.B. The motivational effects of charismatic leadership: A self-concept based theory. Organ. Sci. 1993, 4, 577–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.H.; Solomon, G.T.; Choi, D.Y. CEOs’ leadership styles and managers’ innovative behaviour: Investigation of intervening effects in an entrepreneurial context. J. Manag. Stud. 2015, 52, 531–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.D.; Weigert, A. Trust as a social reality. Soc. Forces 1985, 63, 967–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M. The future of leadership in learning organizations. J. Leadersh. Stud. 2000, 7, 18–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dirani, K.M. Measuring the learning organization culture, organizational commitment and job satisfaction in the Lebanese banking sector. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2009, 12, 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvin, D.A.; Edmondson, A.C.; Gino, F. Is yours a learning organization? Harv. Bus. Rev. 2008, 86, 109. [Google Scholar]

- Senge, P. The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization; Doubleday Currency: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, K.E.; Marsick, V.J. Sculpting the Learning Organization: Lessons in the Art and Science of Systemic Change; Jossey-Bass Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, R.B. The ambidextrous organization: Designing dual structures for innovation. Manag. Organ. 1976, 1, 167–188. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Strategy; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Junni, P.; Sarala, R.M.; Taras, V.; Tarba, S.Y. Organizational ambidexterity and performance: A meta-analysis. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 27, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zollo, L.; Marzi, G.; Boccardi, A.; Surchi, M. How to match technological and social innovation: Insights from the biomedical 3D printing industry. Int. J. Transit. Innov. Syst. 2015, 4, 80–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zollo, L.; Marzi, G.; Boccardi, A.; Ciappei, C. Gli effetti della Stampa 3D sulla competitivitaà aziendale: Il caso delle imprese orafe del distretto di Arezzo. Piccola Impresa Small Bus. 2016, 2, 80–100. [Google Scholar]

- Benner, M.J.; Tushman, M.L. Exploitation, exploration, and process management: The productivity dilemma revisited. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2003, 28, 238–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brix, J. Exploring knowledge creation processes as a source of organizational learning: A longitudinal case study of a public innovation project. Scand. J. Manag. 2017, 33, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brix, J. Ambidexterity and organizational learning: Revisiting and reconnecting the literatures. Learn. Organ. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huber, G.P. The Necessary Nature of Future Firms: Attributes of Survivors in a Changing World; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Z.; Yi, Y.; Guo, H. Organizational learning ambidexterity, strategic flexibility, and new product development. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2014, 31, 832–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, T.; Chandler, S.M. Exploration, exploitation, and public sector innovation: An organizational learning perspective for the public sector. Hum. Serv. Organ. Manag. Leadersh. Gov. 2015, 39, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simsek, Z. Organizational ambidexterity: Towards a multilevel understanding. J. Manag. Stud. 2009, 46, 597–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güttel, W.H.; Konlechner, S.W. Continuously hanging by a thread: Managing contextually ambidextrous organizations. Schmalenbach Bus. Rev. 2009, 61, 150–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L.; Rafiq, M. Ambidextrous organizational culture, Contextual ambidexterity and new product innovation: A comparative study of UK and Chinese high-tech Firms. Br. J. Manag. 2014, 25, 58–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luo, C.; Kumar, S.; Mallick, D.N.; Luo, B. Impacts of exploration and exploitation on firm’s performance and the moderating effects of slack: A panel data analysis. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2018, 66, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Ramamurthy, K. Understanding the link between information technology capability and organizational agility: An empirical examination. MIS Q. 2011, 35, 931–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Charitou, C.D.; Markides, C.C. Responses to disruptive strategic innovation. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2003, 44, 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Sheffi, Y.; Rice, J.B., Jr. A supply chain view of the resilient enterprise. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2005, 47, 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Covin, J.G.; Miles, M.P. Strategic use of corporate venturing. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2007, 31, 183–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dychtwald, K.; Erikson, T.J.; Morison, R. Workforce Crisis; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Swisher, V.V.; Hallenbeck, G.S.; Orr, J.E.; Eichinger, R.W.; Lombardo, M.M.; Capretta, C.C. FYI for Learning Agility: A Must-Have Resource for High Potential Development, 2nd ed.; Korn/Ferry International: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bedford, C.L. The Role of Learning Agility in Workplace Performance and Career Advancement. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Corporate Leadership Council. Realizing the Full Potential of Rising Talent; Corporate Executive Board: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Connolly, J.A.; Viswesvaran, C. Assessing the construct validity of a measure of learning agility. In Proceedings of the 17th Annual Conference of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Toronto, ON, Canada, 12–14 April 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, G.; De Meuse, K.; Tang, K.Y. The role of learning agility in executive career success: The results of two field studies. J. Manag. Issues 2013, 25, 108–131. [Google Scholar]

- Dries, N.; Pepermans, R. How to identify leadership potential: Development and testing of a consensus model. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 51, 361–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, P. Agility Shift: Creating Agile and Effective Leaders, Teams, and Organizations; Bibliomotion, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gravett, L.S.; Caldwell, S.A. Learning Agility: The Impact on Recruitment and Retention; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- DeRue, D.S.; Ashford, S.J.; Myers, C.G. Learning agility: In search of conceptual clarity and theoretical grounding. Ind. Organ. Psychol. Perspect. Sci. Pract. 2012, 5, 258–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eichinger, R.W.; Lombardo, M.M. Learning agility as a prime indicator of potential. Hum. Resour. Plan. 2004, 27, 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- McKenna, R.M.; Boyd, T.N.; Yost, P.R. Learning agility in clergy: Understanding the personal strategies and situational factors that enable pastors to learn from experience. J. Psychol. Theol. 2007, 35, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Meuse, K.P.; Dai, G.; Swisher, V.V.; Eichinger, R.W.; Lombardo, M.M. Leadership development: Exploring, clarifying, and expanding our understanding of learning agility. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2012, 5, 280–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, A.M. Pathways and crossroads to institutional leadership. Consult. Psychol. J. Pract. Res. 1998, 50, 131–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Beier, M.E. Learning agility: Not much is new. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2012, 5, 293–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Morales, V.J.; Lloréns-Montes, F.J.; Verdú-Jover, A.J. The effects of transformational leadership on organizational performance through knowledge and innovation. Br. J. Manag. 2008, 19, 299–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCall, M.W., Jr.; Lombardo, M.M.; Morrison, A.M. The Lessons of Experience: How Successful Executives Develop on the Job; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.H. The impact of individual personality on adaptive performance in organizations. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. Res. 2016, 23, 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, E.K.; Park, S.O. Moderating effects of learning agility on relationship the between informal learning activity and adaptive performance of employees at small and medium-sized it companies. Korea Soc. Learn. Perform. 2018, 20, 35–57. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchikhi, H. Living with and building on complexity: A constructivist perspective on organizations. Organization 1998, 5, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earley, P.C.; Gibson, C.B. Multinational Work Teams: A New Perspective; Lawrence Eribaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ghoshal, S.; Bartlett, C.A. Linking organizational context and managerial action: The dimensions of quality of management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1994, 15, 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, Y.J. Defining the effects of transformational leadership on organisational learning: A cross-cultural comparison. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2002, 22, 439–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, K.A. Transformational leadership and employee psychological well-being: A review and directions for future research. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, K.A.; Turner, N.; Barling, J.; Kelloway, E.K.; McKee, M.C. Transformational leadership and psychological well-being: The mediating role of meaningful work. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2007, 12, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bledow, R.; Frese, M.; Anderson, N.; Erez, M.; Farr, J. A dialectic perspective on innovation: Conflicting demands, multiple pathways, and ambidexterity. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2009, 2, 305–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, F.; Ikram, A.; Jafri, S.K.; Naveed, K. Product Innovations through Ambidextrous Organizational Culture with Mediating Effect of Contextual Ambidexterity: An Empirical Study of IT and Telecom Firms. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zain, M.; Rose, R.C.; Abdullah, I.; Masrom, M. The relationship between information technology acceptance and organizational agility in Malaysia. Inf. Manag. 2005, 42, 829–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, M.; Jung, B.G.; Joo, J.H. A study on multi-level model in organization research: Based on hierarchical linear model. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. Res. 2013, 20, 75–97. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, H.M. Multi-Level Analysis of the Factors Affecting Scale-Up Aspiration in Startups. Ph.D. Thesis, Jungang University, Seoul, Korea, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zang, Z.; Waldman, D.A.; Wang, Z. A multilevel investigation of leader-member exchange, informal leader emergence, and individual and team performance. Pers. Psychol. 2012, 65, 49–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, W.W.; Go, S.K. Multilevel analysis procedures and methods-focused on WABA. Inst. Manag. Res. 2005, 39, 59–90. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B.M.; Avolio, B.J. Full Range Leadership Development: Manual for the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire; Mind Garden: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Yukl, G. An evaluation of conceptual weaknesses in transformational and charismatic leadership theories. Leadersh. Q. 1999, 10, 285–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukl, G. An evaluative essay on current conceptions of effective leadership. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 1999, 8, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awamleh, R.; Gardner, W.L. Perceptions of leader charisma and effectiveness: The effects of vision content, delivery, and organizational performance. Leadersh. Q. 1999, 10, 345–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.J.; Bass, B.M.; Jung, D.I. Re-examining the components of transformational and transactional leadership using the Multifactor Leadership. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 1999, 72, 441–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.L.; Wong, P.K. Exploration vs. exploitation: An empirical test of the ambidexterity hypothesis. Organ. Sci. 2004, 15, 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, C.H.; Wee, Y.E.; Lee, H.S. A study on the development of the learning agility scale. Korean J. Hum. Resour. Dev. 2017, 19, 81–108. [Google Scholar]

- Spreitzer, G.M.; McCall, M.W.; Mahoney, J.D. Early identification of international executive potential. J. Appl. Psychol. 1997, 82, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vroom, V.H. Work and Motivation; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1964; p. 45. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, D.I.; Avolio, B.J. Opening the black box: An experimental investigation of the mediating effects of trust and value congruence on transformational and transactional leadership. J. Organ. Behav. 2000, 21, 949–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.J.; Bass, B.M. Transformational Leadership, Charisma, and Beyond; Lexington Books: Lanham, MD, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Beyerlein, M.; Collins, R.; Jeong, S.; Phillips, C.; Sunalai, S.; Xie, L. Knowledge sharing and human resource development in innovative organizations. In Knowledge Management Strategies and Applications, 1st ed.; Mohiuddin, M., Halilem, N., Kobir, A., Yuliang, C., Eds.; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Brix, J. Building capacity for sustainable innovation: A field study of the transition from exploitation to exploration and back again. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 268, 122381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, D.; Thongpapanl, N.T.; Dimov, D. Shedding new light on the relationship between contextual ambidexterity and firm performance: An investigation of internal contingencies. Technovation 2013, 33, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- O’Cass, A.; Heirati, N.; Ngo, L.V. Achieving new product success via the synchronization of exploration and exploitation across multiple levels and functional areas. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2014, 43, 862–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Meuse, K.P.; Dai, G.; Hallenbeck, G.S. Learning agility: A construct whose time has come. Consult. Psychol. J. Pract. Res. 2010, 62, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Muchinsky, P.M.; Monahan, C.J. What is person-environment congruence? Supplementary versus complementary models of fit. J. Vocat. Behav. 1987, 31, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).