Impact of Perceived Organizational Support on OCB in the Time of COVID-19 Pandemic in Hungary: Employee Engagement and Affective Commitment as Mediators

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Perceived Organizational Support

2.2. Affective Commitment

2.3. Employees Engagement

2.4. Organizational Citizenship Behavior

2.5. POS and Employees Engagement

2.6. POS and Affective Commitment

2.7. POS and OCB

2.8. Employee Engagement and OCB

2.9. Affective Commitment and OCB

2.10. Employee Engagement as a Mediator between POS and OCB

2.11. Affective Commitment as a Mediator between POS and OCB

3. Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedures

3.2. Measures

3.3. Common Method Bias

3.4. Reliability Test

3.5. Validity Test

3.6. Model Fit

4. Results

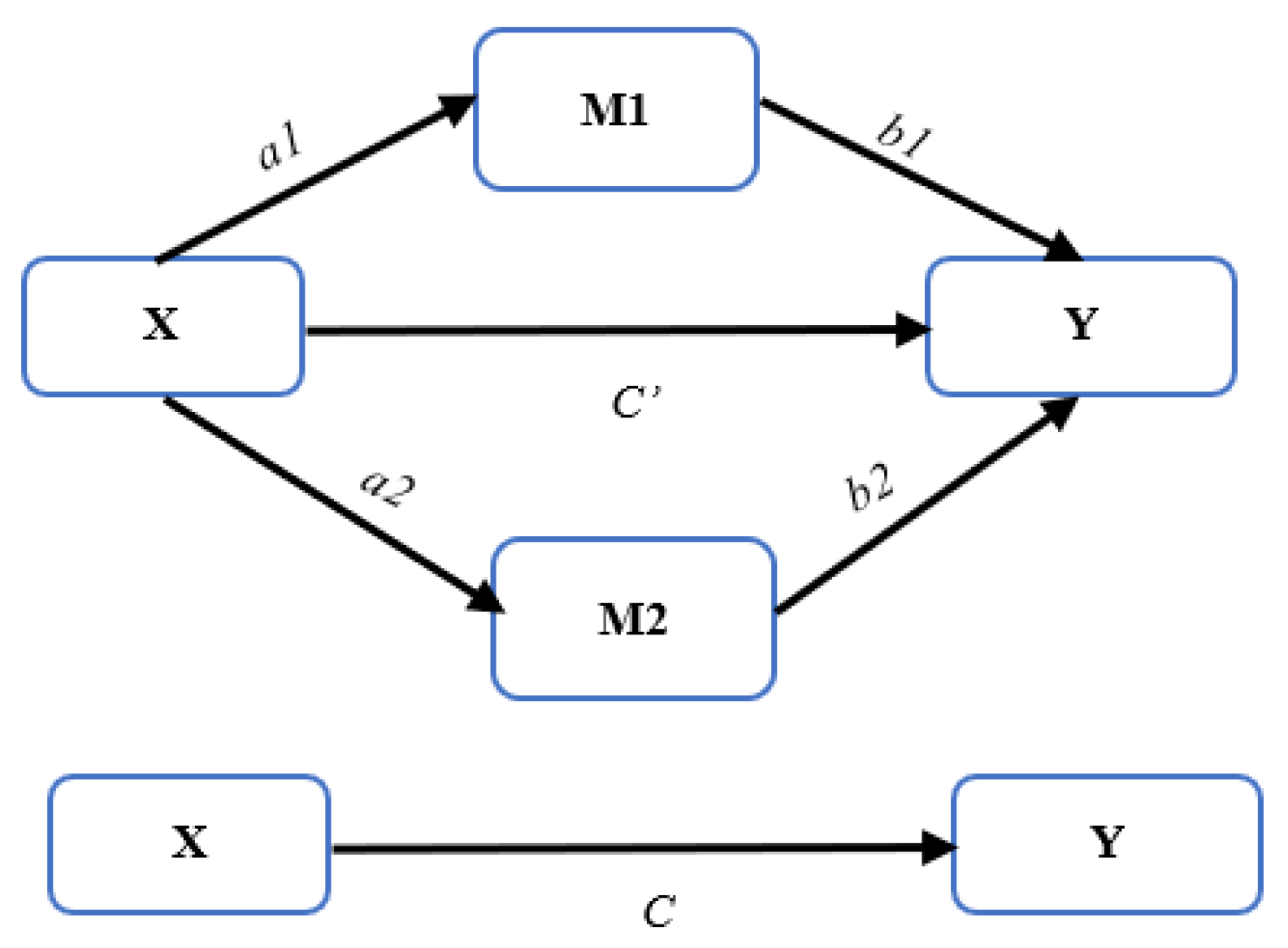

4.1. Data Analysis

- If a, b and c are significant but the direct coefficient value is c < b, then it is partial mediation.

- If a and b are significant, but c is not significant, then it is full mediation.

- If a is significant, b is significant and c is also significant, but the coefficient value is c = b, it is not mediation.

- If a or b or both are insignificant, it is not mediation.

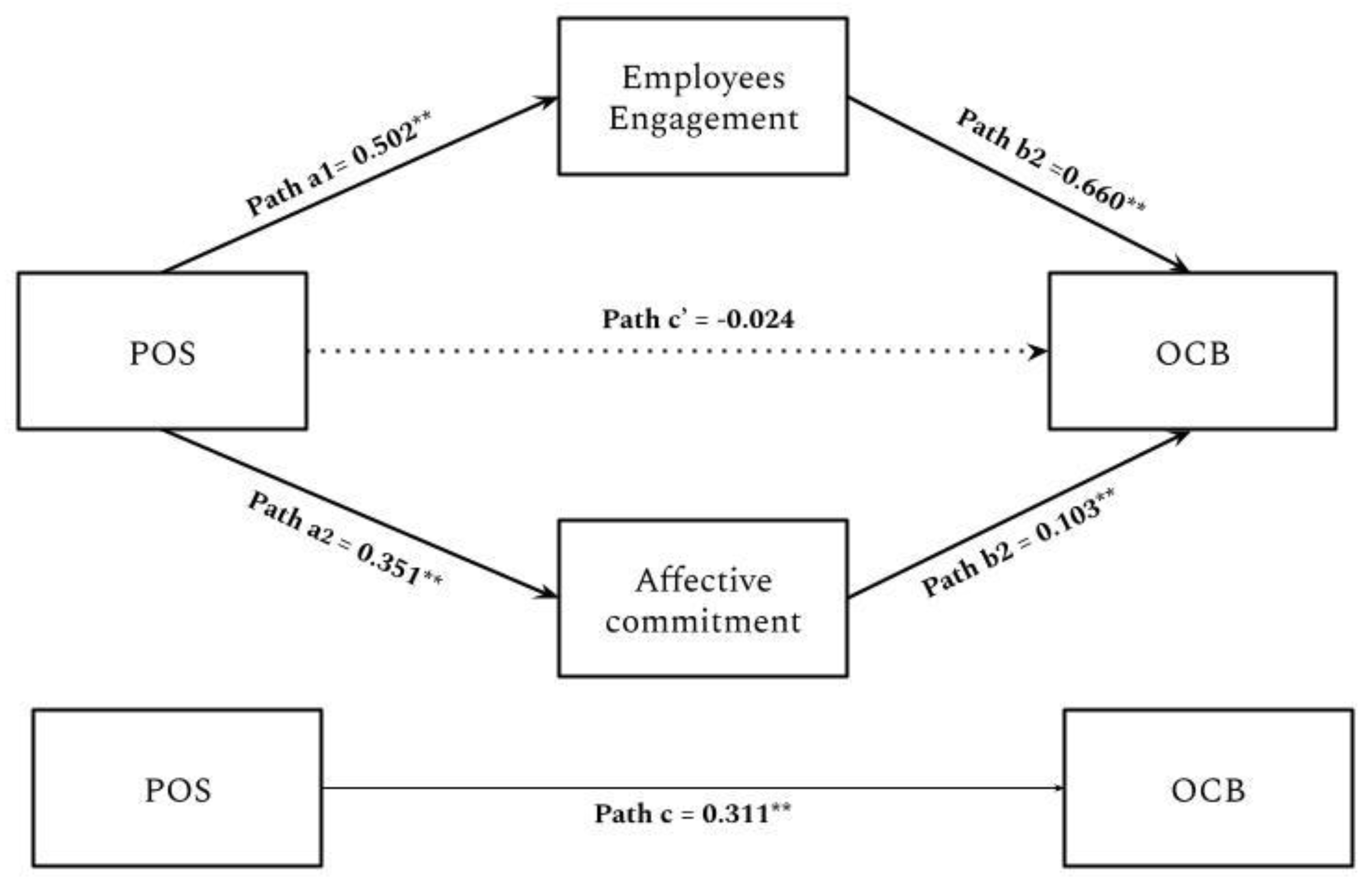

4.2. Hypotheses Test

5. Discussion

6. Theoretical and Practical Implications

7. Conclusions

8. Limitations and Future Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yu, J.; Park, J.; Hyun, S.S. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on employees’ work stress, well-being, mental health, organizational citizenship behavior, and employee-customer identification. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2021, 30, 529–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-Y.; Sun, R.; Tao, W.; Lee, Y. Employee coping with organizational change in the face of a pandemic: The role of transparent internal communication. Public Relat. Rev. 2021, 47, 101984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Main, A.; Zhou, Q.; Ma, Y.; Luecken, L.J.; Liu, X. Relations of SARS-related stressors and coping to Chinese college students’ psychological adjustment during the 2003 Beijing SARS epidemic. J. Couns. Psychol. 2011, 58, 410–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oláh, J.; Hajduová, Z.; Lacko, R.; Andrejovský, P. Quality of Life Regional Differences: Case of Self-Governing Regions of Slovakia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2924. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/12/7/2924 (accessed on 9 June 2021). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaushik, M.; Guleria, N. The Impact of Pandemic COVID -19 in Workplace. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2020, 12, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prem, R.; Ohly, S.; Kubicek, B.; Korunka, C. Thriving on challenge stressors? Exploring time pressure and learning demands as antecedents of thriving at work. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 108–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gunay, S.; Kurtulmuş, B.E. COVID-19 social distancing and the US service sector: What do we learn? Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2021, 56, 101361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, S.; Rasool, S.; Hang, Y.; Javid, K.; Javed, T.; Artene, A.E. The Effect of COVID-19 Pandemic on Service Sector Sustainability and Growth. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 633597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daraba, D.; Wirawan, H.; Salam, R.; Faisal, M. Working from home during the corona pandemic: Investigating the role of authentic leadership, psychological capital, and gender on employee performance. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2021, 8, 1885573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Situation Report-101, Coronovirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200430-sitrep-101-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=2ba4e093_2 (accessed on 5 June 2021).

- Gursoy, D.; Chi, C.G. Effects of COVID-19 pandemic on hospitality industry: Review of the current situations and a research agenda. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2020, 29, 527–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Lee, C.-C.; Xing, W.; Ho, S.-J. The impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on Chinese-listed tourism stocks. Financ. Innov. 2021, 7, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakner, Z.; Kiss, A.; Merlet, I.; Oláh, J.; Máté, D.; Grabara, J.; Popp, J. Building Coalitions for a Diversified and Sustainable Tourism: Two Case Studies from Hungary. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1090. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/10/4/1090 (accessed on 9 June 2021). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hakim, M.P.; Zanetta, L.D.A.; da Cunha, D.T. Should I stay, or should I go? Consumers’ perceived risk and intention to visit restaurants during the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil. Food Res. Int. 2021, 141, 110152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, K.; Nhamo, G.; Chikodzi, D. COVID-19 pandemic and prospects for recovery of the global aviation industry. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2021, 92, 102022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loske, D. The impact of COVID-19 on transport volume and freight capacity dynamics: An empirical analysis in German food retail logistics. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020, 6, 100165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.K.C.; Sriphon, T. Perspective on COVID-19 Pandemic Factors Impacting Organizational Leadership. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3230. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/13/6/3230 (accessed on 25 May 2021). [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.K.F.; Kim, S.; Kim, J.; Han, H. How the COVID-19 pandemic affected hotel Employee stress: Employee perceptions of occupational stressors and their consequences. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 93, 102798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulińska-Stangrecka, H.; Bagieńska, A. The Role of Employee Relations in Shaping Job Satisfaction as an Element Promoting Positive Mental Health at Work in the Era of COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimonau, V.; Derqui, B.; Matute, J. The COVID-19 pandemic and organisational commitment of senior hotel managers. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 91, 102659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narayanamurthy, G.; Tortorella, G. Impact of COVID-19 outbreak on employee performance—Moderating role of industry 4.0 base technologies. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2021, 234, 108075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Fan, X.; Álvarez-Otero, S.; Sial, M.S.; Comite, U.; Cherian, J.; Vasa, L. CSR and Workplace Autonomy as Enablers of Workplace Innovation in SMEs through Employees: Extending the Boundary Conditions of Self-Determination Theory. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6104. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/13/11/6104 (accessed on 9 June 2021). [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T.; Shahid Khan, M.; Thitivesa, D.; Siraphatthada, Y.; Phumdara, T. Impact of employees engagement and knowledge sharing on organizational performance: Study of HR challenges in COVID-19 pandemic. Hum. Syst. Manag. 2020, 39, 589–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.S.; Jung, Y.S.; Yoon, H.H. COVID-19: The effects of job insecurity on the job engagement and turnover intent of deluxe hotel employees and the moderating role of generational characteristics. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 92, 102703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenberger, R.; Malone, G.P.; Presson, W.D. Optimizing perceived organizational support to enhance employee engagement. Soc. Hum. Resour. Manag. Soc. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2016, 2, 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Karkoulian, S.K.; Messarra, L. Organizational commitment recall in times of crisis. J. Int. Bus. Res. 2008, 7, 109–118. [Google Scholar]

- Labrague, L.J.; de los Santos, J.A.A. COVID-19 anxiety among front-line nurses: Predictive role of organisational support, personal resilience and social support. J. Nurs. Manag. 2020, 28, 1653–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Eyoun, K. Do mindfulness and perceived organizational support work? Fear of COVID-19 on restaurant frontline employees’ job insecurity and emotional exhaustion. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 94, 102850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musenze Ibrahim, A.; Thomas, S.M.; Kalenzi, A.; Namono, R. Perceived organizational support, self-efficacy and work engagement: Testing for the interaction effects. J. Econ. Adm. Sci. 2021. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuti, A.; Giancaspro, M.L.; Molino, M.; Ingusci, E.; Russo, V.; Signore, F.; Zito, M.; Cortese, C.G. “Everything Will Be Fine”: A Study on the Relationship between Employees’ Perception of Sustainable HRM Practices and Positive Organizational Behavior during COVID19. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10216. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/12/23/10216 (accessed on 23 May 2021). [CrossRef]

- Guadagno, L. Migrants and the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Initial Analysis. International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2020. Available online: https://publications.iom.int/books/mrs-no-60-migrants-and-covid-19-pandemic-initial-analysis (accessed on 5 June 2021).

- Rudolph, C.W.; Allan, B.; Clark, M.; Hertel, G.; Hirschi, A.; Kunze, F.; Shockley, K.; Shoss, M.; Sonnentag, S.; Zacher, H.; et al. Pandemics: Implications for research and practice in industrial and organizational psychology. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2021, 14, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baksa, M.; Marciniak, R.; Nagy, D. Business Services Sector Hungary; Marciniak, R., Ránki, R., Eds.; Hungarian Service and Outsourcing Association (HOA): Budapest, Hungary, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Medve, F. Number of full-time international students at Hungarian universities from 2009 to 2021. Educ. Sci. 2021. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1094687/hungary-international-university-students/ (accessed on 25 June 2021).

- Pongratz, N. More than 33,000 foreign students in Hungary. Bp. Bus. J. 2020. Available online: https://bbj.hu/economy/statistics/analysis/more-than-33-000-foreign-students-in-hungary (accessed on 25 June 2021).

- EUGO. Key facts about Hungary. Hung. Point Single Contact. 2020. Available online: http://eugo.gov.hu/key-facts-about-hungary/economy (accessed on 9 June 2021).

- Eisenberger, R.; Huntington, R.; Hutchison, S.; Sowa, D. Perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.K.; Sinha, A.K. General Health in Organizations: Relative Relevance of Emotional Intelligence, Trust, and Organizational Support. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2005, 12, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoades, L.; Eisenberger, R. Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, P.B.; Lei, H. Determinants of innovation capability: The roles of transformational leadership, knowledge sharing and perceived organizational support. J. Knowl. Manag. 2019, 23, 527–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J. Commitment in the Workplace: Theory, Research, and Application; SAGE Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1997; Available online: https://books.google.hu/books?id=jn4VFpFJ2qQC (accessed on 21 May 2021).

- Meyer, J.P.; Stanley, D.J.; Herscovitch, L.; Topolnytsky, L. Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: A meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. J. Vocat. Behav. 2002, 61, 20–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colakoglu, U.; Culha, O.; Atay, H. The effects of perceived organisational support on employees’ affective outcomes: Evidence from the hotel industry. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 16, 125–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, J.-W.; Price, J.L.; Mueller, C.W. Assessment of Meyer and Allen’s three-component model of organizational commitment in South Korea. J. Appl. Psychol. 1997, 82, 961–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, A.H. Perceived organizational support and organizational citizenship behavior: The case of Kuwait. Int. J. Bus. Adm. 2014, 5, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rameshkumar, M. Employee engagement as an antecedent of organizational commitment—A study on Indian seafaring officers. Asian J. Shipp. Logist. 2020, 36, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, O.; Islam, J.U. Enhancing organizational commitment and employee performance through employee engagement: An empirical check. South Asian J. Bus. Stud. 2017, 6, 98–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Salanova, M.; González-romá, V.; Bakker, A.B. The Measurement of Engagement and Burnout: A Two Sample Confirmatory Factor Analytic Approach. J. Happiness Stud. 2002, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, D.; Perryman, S.; Hayday, S. The Drivers of Employee Engagement; Institute for Employment Studies: Brighton, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Downey, S.N.; van der Werff, L.; Thomas, K.M.; Plaut, V.C. The role of diversity practices and inclusion in promoting trust and employee engagement. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 45, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshaabani, A.; Naz, F.; Rudnák, I. Impact of Green Human Resources Practices on Green Work Engagement in the Renewable Energy Departments. Int. Bus. Res. 2021, 14, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshaabani, A.; Oláh, J.; Popp, J.; Zaien, S. Impact of Distributive Justice on The Trust Climate Among Middle Eastern Employees. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2020, 21, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saks, A.M. Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. J. Manag. Psychol. 2006, 21, 600–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ghosh, P.; Rai, A.; Sinha, A. Organizational justice and employee engagement. Pers. Rev. 2014, 34, 628–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.; Bhatnagar, J. Mediator Analysis of Employee Engagement: Role of Perceived Organizational Support, P-O Fit, Organizational Commitment and Job Satisfaction. Vikalpa 2013, 38, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Macey, W.H.; Schneider, B. The Meaning of Employee Engagement. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2008, 1, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einarsen, S.; Skogstad, A.; Rørvik, E.; Lande, Å.B.; Nielsen, M.B. Climate for conflict management, exposure to workplace bullying and work engagement: A moderated mediation analysis. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 29, 549–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandani, A.; Mehta, M.; Mall, A.; Khokhar, V. Employee Engagement: A Review Paper on Factors Afecting Employee Engagement. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2016, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.Y.; Elahi, N.S.; Abid, G.; Ashfaq, F.; Ilyas, S. Impact of Perceived Organizational Support on Work Engagement: Mediating Mechanism of Thriving and Flourishing. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jehanzeb, K. Does perceived organizational support and employee development influence organizational citizenship behavior? Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2020, 44, 637–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisha Chanana, S. Employee engagement practices during COVID-19 lockdown. J. Public Aff. 2020, e2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bies, R. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Good Soldier Syndrome. J. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 294–297. Available online: www.jstor.org/stable/258426 (accessed on 8 June 2021). [CrossRef]

- Organ, D.W. Organizational citizenship behavior: It’s construct clean-up time. Hum. Perform. 1997, 10, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahangir, N.; Akbar, M.M.; Haq, M. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Its Nature and Antecedents. BRAC Univ. J. 2004, 1, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bienstock, C.C.; DeMoranville, C.W.; Smith, R.K. Organizational citizenship behavior and service quality. J. Serv. Mark. 2003, 17, 357–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriyanti, N.P.V.; Supartha, I.W.G. Effect of perceived organizational support on organizational citizenship behavior with work satisfaction as mediating variables. Am. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Res. (AJHSSR) 2021, 1, 46–55. [Google Scholar]

- Foote, D.A.; Tang, T.L. Job satisfaction and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB). Manag. Decis. 2008, 46, 933–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jiao, C.; Richards, D.A.; Zhang, K. Leadership and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: OCB-Specific Meanings as Mediators. J. Bus. Psychol. 2011, 26, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suliman, A.; al Obaidli, H. Leadership and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) in the financial service sector. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2013, 5, 115–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifta Firdausa, N.; Ema, N. The influence of distributive justice, job satisfaction and affective commitment to organizational citizenship behavior. Rev. Produção E Desenvolv. 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartika, E.W.; Pienata, C. The Role of Organizational Commitment on Organizational Citizenship Behavior in Hotel Industry. J. Manaj. 2020, 24, 373–391. [Google Scholar]

- Atrizka, D.; Lubis, H.; Simanjuntak, C.W.; Pratama, I. Ensuring Better Affective Commitment and Organizational Citizenship Behavior through Talent Management and Psychological Contract Fulfillment: An Empirical Study of Indonesia Pharmaceutical Sector. Syst. Rev. Pharm. 2020, 11, 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariani, D.W. The relationship between employee engagement, organizational citizenship behavior, and counterproductive work behavior. Int. J. Bus. Adm. 2013, 4, 46. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, W.A. Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 692–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Byrne, Z.S.; Hochwarter, W.A. Perceived organizational support and performance: Relationships across levels of organizational cynicism. J. Manag. Psychol. 2008, 23, 54–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Huang, H.; Qiu, T.; Tian, F.; Gu, Z.; Gao, X.; Wu, H. Psychological Capital Mediates the Association Between Perceived Organizational Support and Work Engagement Among Chinese Doctors. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Björk, P.; Ravald, A. Exploring the effects of service provider’s organizational support and empowerment on employee engagement and well-being. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2020, 7, 1767329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caesens, G.; Stinglhamber, F. The relationship between perceived organizational support and work engagement: The role of self-efficacy and its outcomes. Eur. Rev. Appl. Psychol. 2014, 64, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Social exchange theory. Int. Encycl. Soc. Sci. 1964, 3, 62. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Peccei, R. Perceived organizational support and affective commitment: The mediating role of organization-based self-esteem in the context of job insecurity. J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 2007, 28, 661–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Mitchell, M.S. Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Cropanzano, R.; Goldman, B.M. How Leader–Member Exchange Influences Effective Work Behaviors: Social Exchange and Internal–External Efficacy Perspectives. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 64, 739–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, P.R.J.M.; Amarnani, R.K.; Bordia, P.; Restubog, S.L.D. When support is unwanted: The role of psychological contract type and perceived organizational support in predicting bridge employment intentions. J. Vocat. Behav. 2021, 125, 103525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoa, N.D.; Ngan, P.T.; Quang, N.M.; Thanh, V.B.; Quyen, H.V. An empirical study of perceived organizational support and affective commitment in the logistics industry. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. Manag. Econ. Eng. 2020, 7, 589–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, I.; Elahi, N.S.; Abid, G.; Butt, M.U. The impact of perceived organizational support and proactive personality on affective commitment: Mediating role of prosocial motivation. Bus. Manag. Econ. Eng. 2020, 18, 183–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayne, S.J.; Shore, L.M.; Bommer, W.H.; Tetrick, L.E. The role of fair treatment and rewards in perceptions of organizational support and leader-member exchange. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 590–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azim, A.M.M.; Dora, M.T. Perceived organizational support and organizational citizenship behavior: The mediating role of psychological capital. J. Hum. Cap. Dev. 2016, 9, 99–118. [Google Scholar]

- Organ, D.W.; Paine, J.B. A new kind of performance for industrial and organizational psychology: Recent contributions to the study of organizational citizenship behavior. Int. Rev. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 1999, 14, 337–368. [Google Scholar]

- Spector, P.E.; Che, X.X. Re-examining citizenship: How the control of measurement artifacts affects observed relationships of organizational citizenship behavior and organizational variables. Hum. Perform. 2014, 27, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konovsky, M.A.; Pugh, S.D. Citizenship behavior and social exchange. Acad. Manag. J. 1994, 37, 656–669. [Google Scholar]

- Settoon, R.P.; Bennett, N.; Liden, R.C. Social exchange in organizations: Perceived organizational support, leader–member exchange, and employee reciprocity. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 81, 219. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, F.H.; Rizavi, S.S.; Ahmed, I.; Rasheed, M. Effects of perceived organizational support on organizational citizenship behavior–Sequential mediation by well-being and work engagement. J. Punjab Univ. Hist. Soc. 2018, 31, 111–131. [Google Scholar]

- Wayne, S.J.; Shore, L.M.; Liden, R.C. Perceived organizational support and leader-member exchange: A social exchange perspective. Acad. Manag. J. 1997, 40, 82–111. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, N. Effects of Perceived Organizational Support and Leader-Member Exchange on Organizational Citizenship Behavior. J. Manag. Sci. 2009, 3, 53–56. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, T.; Khan, S.u.R.; Ahmad, U.N.U.; Ahmed, I. Exploring the Relationship Between POS, OLC, Job Satisfaction and OCB. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 114, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bartkowiak, G.; Krugiełka, A.; Dachowski, R.; Gałek, K.; Kostrzewa-Demczuk, P. Attitudes of Polish Entrepreneurs towards 65+ Knowledge Workers in the Context of Their Pro-Social Attitude and Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5294. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/12/13/5294 (accessed on 26 June 2021). [CrossRef]

- Thakre, N.; Mathew, P. Psychological empowerment, work engagement, and organizational citizenship behavior among Indian service-sector employees. GBOE 2020, 39, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulea, C.; Virga, D.; Maricutoiu, L.P.; Schaufeli, W.; Dumitru, C.Z.; Sava, F.A. Work engagement as mediator between job characteristics and positive and negative extra-role behaviors. Career Dev. Int. 2012, 17, 188–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jin, M.H.; McDonald, B. Understanding Employee Engagement in the Public Sector: The Role of Immediate Supervisor, Perceived Organizational Support, and Learning Opportunities. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2016, 47, 881–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saradha, H.; Patrick, H.A. Employee engagement in relation to organizational citizenship behavior in information technology organizations. J. Mark. Manag. 2011, 2, 74–90. [Google Scholar]

- Obedgiu, V.; Bagire, V.; Mafabi, S. Examination of organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behaviour among local government civil servants in Uganda. J. Manag. Dev. 2017, 36, 1304–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, D.C. The Dilbert Syndrome: How Employee Cynicism about Ineffective Management is Changing the Nature of Careers in Organizations. Am. Behav. Sci. 2000, 43, 1286–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ma, L.; Zhang, M. Transformational leadership and agency workers’ organizational commitment: The mediating effect of organizational justice and job characteristics. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2014, 42, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-Y.; Hight, S.K.; Bufquin, D.; de Souza Meira, J.V.; Back, R.M. An examination of restaurant employees’ work-life outlook: The influence of support systems during COVID-19. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 97, 102992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masterson, S.S.; Lewis, K.; Goldman, B.M.; Taylor, M.S. Integrating justice and social exchange: The differing effects of fair procedures and treatment on work relationships. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 738–748. [Google Scholar]

- Shams, M.S.; Niazi, M.M.; Asim, F. The Relationship Between Perceived Organizational Support, Employee Engagement, and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Application of PLS-SEM Approach. Kardan J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2020, 3, 35–55. [Google Scholar]

- Karatepe, O.M. High-performance work practices and hotel employee performance: The mediation of work engagement. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 32, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piercy, N.F.; Cravens, D.W.; Lane, N.; Vorhies, D.W. Driving organizational citizenship behaviors and salesperson in-role behavior performance: The role of management control and perceived organizational support. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2006, 34, 244–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valeau, P.J.; Paillé, P. The management of professional employees: Linking progressive HRM practices, cognitive orientations and organizational citizenship behavior. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2019, 30, 2705–2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Perceived organizational support and expatriate organizational citizenship behavior. Pers. Rev. 2009, 38, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruch, Y.; Holtom, B.C. Survey response rate levels and trends in organizational research. Hum. Relat. 2008, 61, 1139–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Allen, N.J.; Meyer, J.P. The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. J. Occup. Psychol. 1990, 63, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.C.; Organ, D.W.; Near, J.P. Organizational citizenship behavior: Its nature and antecedents. J. Appl. Psychol. 1983, 68, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, T.E.; Randall, D.M. Validation of a Measure of Organizational Citizenship Behavior Against an Objective Behavioral Criterion. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1994, 54, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton-Jones, A. Minimizing Method Bias through Programmatic Research. MIS Q. 2009, 33, 445–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of Method Bias in Social Science Research and Recommendations on How to Control It. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sekaran, U.; Bougie, R. Research Methods For Business: A Skill Building Approach; Wiley: West Sussex, UK, 2016; Available online: https://books.google.hu/books?id=Ko6bCgAAQBAJ (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- Kaiser, H.F. An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika 1974, 39, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, P. An Easy Guide to Factor Analysis; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, USA, 2017; Available online: https://books.google.hu/books?id=5wmXDgAAQBAJ (accessed on 8 May 2021).

- Chin, W.W. Commentary: Issues and Opinion on Structural Equation Modeling. MIS Q. 1998, 22, vii–xvi. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/249674 (accessed on 4 May 2021).

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y.; Phillips, L.W. Assessing Construct Validity in Organizational Research. Adm. Sci. Q. 1991, 36, 421–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA; London, UK, 2010; Available online: https://books.google.hu/books?id=SLRPLgAACAAJ (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- Hu, L.t.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, D.; Coughlan, J.; Mullen, M. Structural Equation Modelling: Guidelines for Determining Model Fit. Electron. J. Bus. Res. Methods 2008, 6, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, D. Structural Equation Modeling. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Science; Smelser, N.J., Baltes, P.B., Eds.; Oxford: Pergamon, Turkey, 2001; pp. 15215–15222. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Anderson, R.; Black, B.; Babin, B. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson Education: Harlow, UK, 2016; Available online: https://books.google.hu/books?id=LKOSAgAAQBAJ (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- Dai, K.; Qin, X. Perceived Organizational Support and Employee Engagement: Based on the Research of Organizational Identification and Organizational Justice. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2016, 4, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aubé, C.; Rousseau, V.; Morin, E.M. Perceived organizational support and organizational commitment. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 479–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugianingrat, I.A.; Widyawati, S.R.; da Costa, C.A.; Ximenes, M.; Piedade, S.D.; Sarmawa, W.G. The employee engagement and OCB as mediating on employee performance. Int. J. Product. Manag. 2019, 68, 319–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zou, P.; Lin, S.; Mu, S.; Deng, Q.; Du, C.; Zhou, G.; Wu, J.; Gan, L. Explaining Organizational Citizenship Behavior Among Chinese Nurses Combating COVID-19. Risk Manag. Healthc Policy 2021, 14, 979–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; He, W.; Zhou, K. The mind, the heart, and the leader in times of crisis: How and when COVID-19-triggered mortality salience relates to state anxiety, job engagement, and prosocial behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 105, 1218–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.-C.; Yao-Ping Peng, M.; Wang, L.; Hung, H.K.; Jong, D. Factors Influencing Employees’ Subjective Wellbeing and Job Performance During the COVID-19 Global Pandemic: The Perspective of Social Cognitive Career Theory. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenberghe, C.; Bentein, K.; Stinglhamber, F. Affective commitment to the organization, supervisor, and work group: Antecedents and outcomes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2004, 64, 47–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, I.E.; Elbaz, A.M.; Elkhwesky, Z.; Ghazi, K.M. The COVID-19 pandemic: The mitigating role of government and hotel support of hotel employees in Egypt. Tour. Manag. 2021, 85, 104305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Traits | Item | Count | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 182 | 47.9 |

| Female | 191 | 50.3 | |

| Prefer not to say | 7 | 1.8 | |

| Work tenure | less than one year | 118 | 31.1 |

| More than one year to five years | 183 | 48.1 | |

| More than five years to ten years | 65 | 17.1 | |

| Above ten years | 14 | 3.7 | |

| Age | 18–24 | 61 | 16.1 |

| 25–34 | 262 | 68.9 | |

| 35–44 | 42 | 11.1 | |

| 45–54 | 15 | 3.9 | |

| Above 55 | 0 | 0 | |

| Company’s sector | Hospitality | 25 | 6.6 |

| Tourism | 68 | 17.9 | |

| Financial and trade | 142 | 37.5 | |

| Health care | 10 | 2.5 | |

| Entertainment | 8 | 2.1 | |

| Transportation | 15 | 3.9 | |

| Other | 112 | 29.5 |

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Employees Engagement | 3.775 | 0.973 | - | |||

| 2. Affective commitment | 3.301 | 0.685 | 0.258 ** | - | ||

| 3. POS | 3.258 | 0.627 | 0.502 ** | 0.351 ** | - | |

| 4. OCB | 3.242 | 0.560 | 0.671 ** | 0.263 ** | 0.342 ** | - |

| Variables | Items | Items Loadings | CR | AVE | Alphas Cronbach |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employee’s engagement | Eng1 | 0.610 | 0.90 | 0.51 | 0.876 |

| Eng2 | 0.780 | ||||

| Eng3 | 0.761 | ||||

| Eng4 | 0.803 | ||||

| Eng5 | 0.699 | ||||

| Eng6 | 0.664 | ||||

| Eng7 | 0.695 | ||||

| Eng8 | 0.744 | ||||

| Eng9 | 0.662 | ||||

| OCB | OCBs1 | 0.763 | 0.92 | 0.55 | 0.819 |

| OCBs2 | 0.785 | ||||

| OCBs3 | 0.766 | ||||

| OCBs4 | 0.735 | ||||

| OCBs5 | 0.694 | ||||

| OCBs6 | 0.666 | ||||

| OCBs7 | 0.799 | ||||

| OCBs8 | 0.770 | ||||

| OCBs9 | 0.699 | ||||

| OCBs10 | 0.689 | ||||

| POS | POSs1 | 0.786 | 0.83 | 0.608 | 0.734 |

| POSs2 | 0.811 | ||||

| POSs3 | 0.776 | ||||

| POSs4 | 0.681 | ||||

| POSs5 | 0.856 | ||||

| POSs6 | Item deleted.a | ||||

| POSs7 | Item deleted.b | ||||

| POSs8 | 0.710 | ||||

| Affective commitment | AC1 | 0.754 | 0.88 | 0.60 | 0.743 |

| AC2 | 0.763 | ||||

| AC3 | 0.674 | ||||

| AC4 | 0.798 | ||||

| AC5 | 0.790 | ||||

| AC6 | 0.833 |

| Fit Index | χ2 | df | χ2/df | TLI | CFI | RMSEA | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | 3.869 | 1 | 3.869 * | 0.96 | 0.99 | 0.08 | 0.03 |

| Path Code | Structural Paths | Estimate | β | SE | CR | Sig | Information |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path a1 | POS → Employee engagement | 0.779 | 0.502 | 0.069 | 11.301 | *** | Paths a1, b1 are significant, while c’ is not significant: (full mediation), (H1, H4, H6) supported |

| Path b1 | Employee engagement → OCB | 0.378 | 0.660 | 0.033 | 2.512 | 0.012 | |

| Path c’ | POS → OCB | −0.021 | −0.024 | 0.040 | −0.524 | 0.600 | |

| Path a2 | POS → Affective commitment | 0.384 | 0.351 | 0.053 | 7.308 | *** | Paths a2, b2 are significant, while c’ is not significant: (full mediation) (H2, H5, H7) supported) |

| Path b2 | Affective commitment → OCB | 0.083 | 0.103 | 0.025 | 14.964 | *** | |

| Path c | POS → OCB | 0.311 | 0.342 | 0.043 | 7.080 | *** | H3 supported |

| Indirect effects | |||||||

| POS → Employee engagement → OCB | 0.331 | *** | |||||

| POS → Affective commitment → OCB | 0.036 | ** | |||||

| R2 | Affective commitment | 0.124 | |||||

| Employee engagement | 0.252 | ||||||

| Organizational citizenship behavior | 0.453 | ||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alshaabani, A.; Naz, F.; Magda, R.; Rudnák, I. Impact of Perceived Organizational Support on OCB in the Time of COVID-19 Pandemic in Hungary: Employee Engagement and Affective Commitment as Mediators. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7800. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147800

Alshaabani A, Naz F, Magda R, Rudnák I. Impact of Perceived Organizational Support on OCB in the Time of COVID-19 Pandemic in Hungary: Employee Engagement and Affective Commitment as Mediators. Sustainability. 2021; 13(14):7800. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147800

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlshaabani, Ayman, Farheen Naz, Róbert Magda, and Ildikó Rudnák. 2021. "Impact of Perceived Organizational Support on OCB in the Time of COVID-19 Pandemic in Hungary: Employee Engagement and Affective Commitment as Mediators" Sustainability 13, no. 14: 7800. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147800

APA StyleAlshaabani, A., Naz, F., Magda, R., & Rudnák, I. (2021). Impact of Perceived Organizational Support on OCB in the Time of COVID-19 Pandemic in Hungary: Employee Engagement and Affective Commitment as Mediators. Sustainability, 13(14), 7800. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147800