Attitudes of Polish Entrepreneurs towards 65+ Knowledge Workers in the Context of Their Pro-Social Attitude and Organizational Citizenship Behavior

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Considerations

2.1. Attitudes Towards 65+ Knowledge Workers

2.2. The Specificity of Knowledge Workers Functioning

- The ability to compete depends on the quality of the company intellectual capital organization, whose owners and peculiar carriers are knowledge workers;

- The success of the organization depends on the competence of employees;

- Knowledge workers create key competencies for the company;

- Acquiring knowledge workers is costly for the company;

- Enterprises have a great demand for knowledge workers, professionals with experience, creative minded, with high internal motivation.

- Has valuable knowledge for the organization and is often the only person; is a person who is able to use this knowledge for the organization; their knowledge is hidden and unconscious;

- Sometimes the employee is unaware of its importance and importance. Other employees in the organization have limited access to it and are unable (for various reasons, e.g., financial resources, time resources; knowledge workers more often (than other employees) use their intellect, although this is not the rule. The same author emphasized in numerous of his studies that knowledge workers create values for the future of the enterprise.

- The basic tool of knowledge workers’ work is their “intellect”. Their loss is also a loss of the intellectual capital of the organization;

- Knowledge workers use knowledge in their work, by creating it, sharing knowledge and using it in both explicit and tacit knowledge;

- Maintaining the professional position of knowledge workers requires them to continually improve through learning;

- Knowledge workers create new value for the organization through their actions and accumulating knowledge;

- Knowledge workers change their jobs by following their own path. Their characteristic feature is the constant desire to change the nature of their work;

- The productivity and quality of their work is difficult to measure;

- Knowledge workers organize their workday themselves. Maintaining their professional position requires creative thinking, possessing competencies that allow them to solve problems. For this reason, they do not accept management’s imposing on them ways of performing certain tasks.

2.3. The Essence of Pro-Social Behavior

3. Citizenship Behavior in the Organization

3.1. Dynamics of Concept Formation

- Altruism as help directed at another employee in dealing with a specific professional problem, e.g., support in the implementation of a difficult task, help in completing overdue tasks, etc.;

- OCB-1 as behavior that brings immediate help to a specific person, e.g., as assistance in duties after a prolonged absence, which is also beneficial to the entire organization;

- Assistance directed to co-workers as a voluntary form of assistance, thanks to which support is provided in achieving goals and tasks (e.g., appropriate distribution of resources, support for people most burdened with work, etc.);

- Interpersonal facilitation, which consists of other collaborator-oriented behaviors;

- OCB-Behaviors directed at organizations that contribute to improving the image of the organization, promote efficiency. These behaviors help the organization achieve its goals more easily.

3.2. OCB Focused on Providing Help and Related to the Functioning of the Organization

3.3. Citizenship Behavior and Pro-Social Behavior

4. Research Issues and Methodology

- What are the attitudes of entrepreneurs, and what is their relation to the employment of 65+ knowledge workers in 2014 and 2019, in the context of applicable legal regulations?

- To what extent do certain attitudes towards employing knowledge workers who are older than 65 depend on the pro-social attitude of entrepreneurs?

- To what extent do certain attitudes towards employing 65+ knowledge workers depend on citizenship behavior, and in particular in the aspect of citizenship organizational behavior and/or citizenship assistance (bringing person help) behavior?

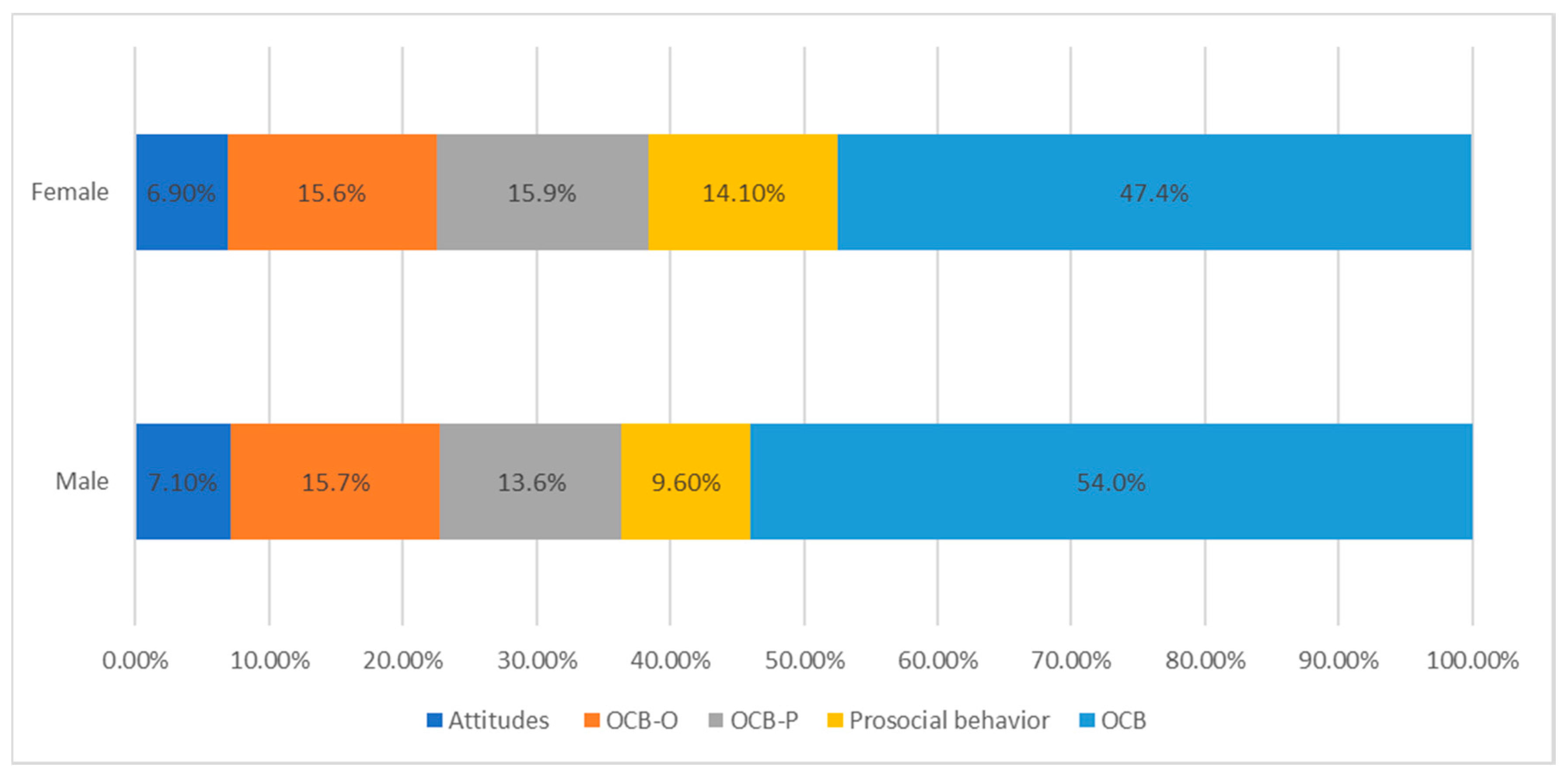

- Is the gender of entrepreneurs a factor determining attitudes towards 65+ knowledge employees, citizenship behavior (including organizational and assistance) and pro-social behavior?

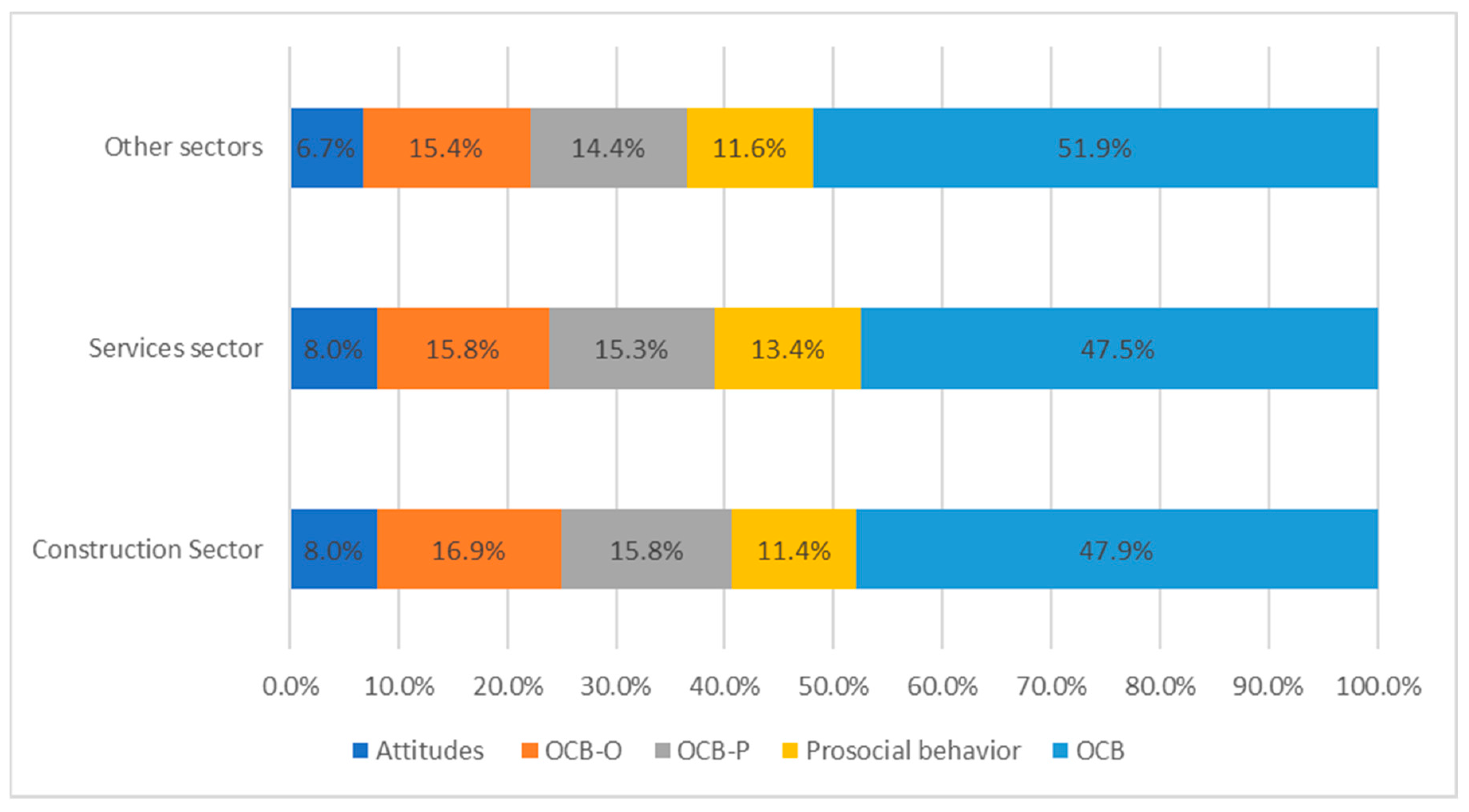

- Is there a difference in the attitudes of entrepreneurs towards 65+ knowledge workers, their citizenship behavior (including organizational and assistance) and pro-social behavior in the service sector (including construction companies) and other business sectors?

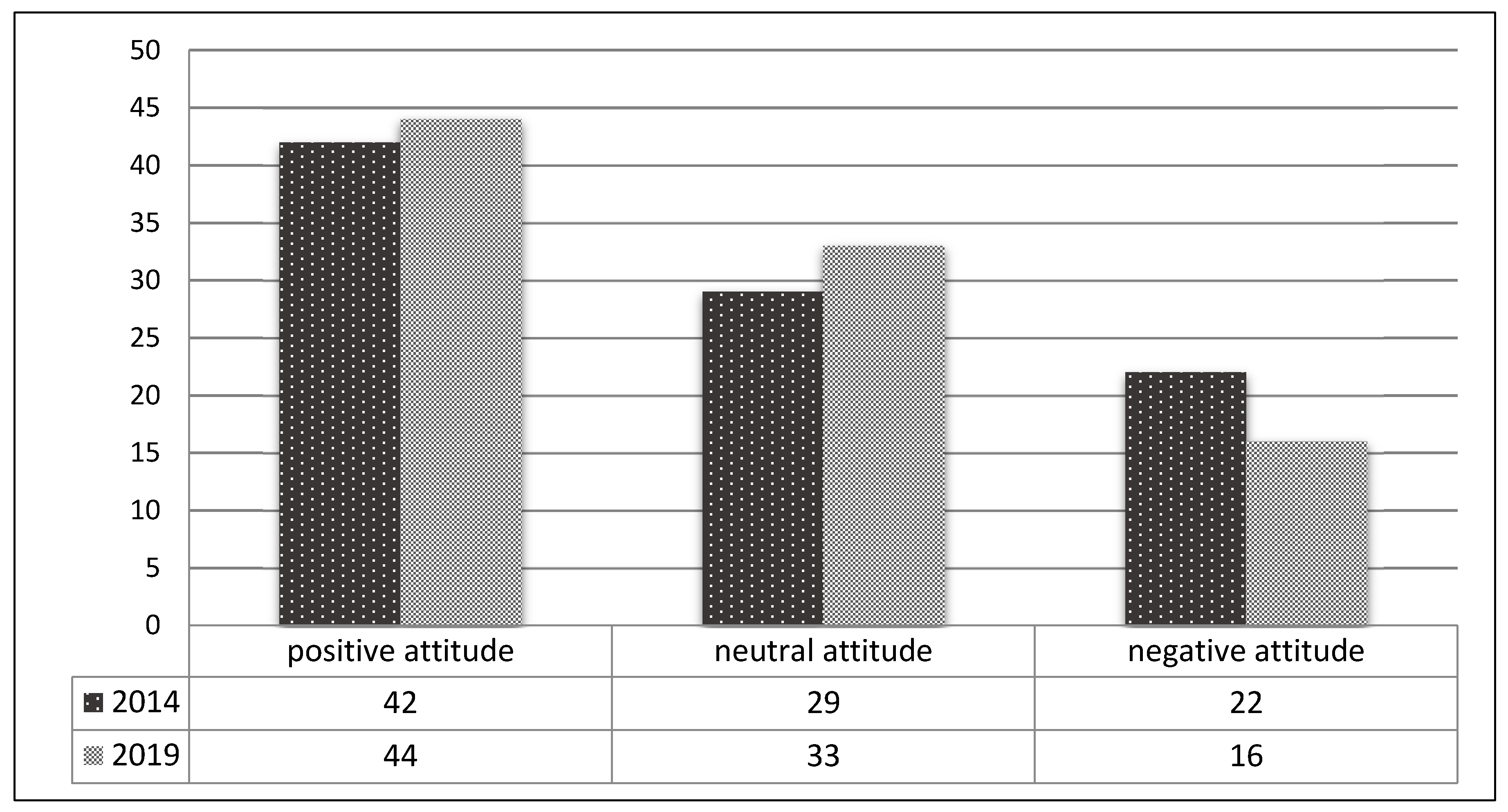

- Hypothesis 1. The attitudes of entrepreneurs towards knowledge workers are varied, in most cases (positive and persistent), both periods studied.

- Hypothesis 2. More positive attitudes towards employing 65+ knowledge workers are found in entrepreneurs with a higher level of pro-social attitude.

- Hypothesis 3. More positive attitudes of entrepreneurs towards knowledge workers are accompanied by a higher level of organizational citizenship behavior, and in particular, behavior related to the organization than assistance behavior.

- Hypothesis 4. The attitudes of entrepreneurs towards 65+ knowledge workers and citizenship and pro-social behavior differ depending on their gender.

- Hypothesis 5. There is a difference between entrepreneurs’ attitudes towards 65+ knowledge workers, citizenship behavior and pro-social attitude of entrepreneurs from the sector of service companies (including construction companies) compared to companies from the other sectors.

4.1. Description of the Research Sample

4.2. Description of the Research Tool

5. Findings

5.1. Attitudes of Entrepreneurs Towards 65+ Knowledge Workers

5.2. Attitudes Entrepreneurs Towards 65+ Employees Knowledge, Citizenship Behavior, and Pro-Social Behavior

5.3. Attitudes Towards 65+ Knowledge Workers, Citizenship Behavior and Pro-Social Behavior Depending on the Gender of Entrepreneurs and on the Business Sector

6. Discussion of Results and Conclusions of the Research

- From the point of view of a 65+ knowledge worker, positive entrepreneurial attitudes build their confidence in the organization, increase the sense of security of employment after retirement, even if they experience some health problems and create opportunities to negotiate the scope and content of their work. This situation certainly contributes to improving their well-being and improves the subjectively assessed quality of life.

- From the organization’s point of view, positive attitudes towards mature knowledge workers and the associated perception of the advantage of benefits over the risks arising from the employment of this group of people means that they will be willing to use their intellectual and social capital. In this way, entrepreneurs optimize human capital management in the organization, and do not allow it to be wasted. At the same time, the observed modification of good practices used, enabling the modification of work in late adulthood, can cause that depending on the needs, they will modify, create and implement subsequent practices.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gladwin, T.N.; Kennelly, J.J.; Krause, T.S. Shifting paradigms for sustainable development. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 874–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starik, M.; Marcus, A.A. Introduction to the special research forum on the management of organizations in the natural environment. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 539–546. [Google Scholar]

- Etzion, D. Research on organizations and the natural environment, 1992-present: A review. J. Manag. 2007, 33, 637–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffa, F.; Frach, M.; Rizo, D. Environmental management practices for sustainable business models in small and medium hotel enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 194, 656–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birau, F.R.; Dănăcică, D.E.; Spulbar, C.M. Social Exclusion and Labor Market Integration of People with Disabilities. A Case Study for Romania. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marnewick, C.; Silvius, G.; Schipper, R. Exploring Patterns of Sustainability Stimuli of Project Managers. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stypinska, J.; Turek, K. Hard and soft age discrimination: The dual nature of workplace discrimination. Eur. J. Ageing 2017, 14, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, P.; Wolff, J.K.; Rothermund, K. Relations between views on ageing and perceived age discrimination: A domain-specific perspective. Eur. J. Ageing 2016, 14, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, R.; Giles, H. Ageism in workplace: A communication perspective. In Ageism: Stereotyping Against Older Person; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004; pp. 163–199. [Google Scholar]

- Rupp, D.E.; Vodanovich, S.J.; Crede, M. Age bias in the work place: The impact of ageism and casual attributions. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 36, 1337–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Report on Poland’s Intellectual Capital. Available online: https://kramarz.pl/Raport_2008_Kapital_Intelektualny_Polski.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2020).

- GUS. Population Forecast until 2030. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/ludnosc/prognoza-ludnosci/prognoza-ludnosci-na-lata-2003-2030,1,2.html (accessed on 27 May 2020).

- WHO. World Report on Ageing and Health 2015. Available online: https://www.who.int/ageing/events/world-report-2015-launch/en/ (accessed on 27 May 2020).

- Journal of Laws of 13 May 2012. Available online: https://static1.money.pl/d/akty_prawne/pdf/DU/2012/0/DU20120000637.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2020).

- Journal of Laws of November 16, 2016. Available online: https://static1.money.pl/d/akty_prawne/pdf/DU/2017/0/DU20170000038.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2020).

- Report on the State of the SME Sector in Poland, Warsaw. 2019. Available online: https://www.parp.gov.pl/storage/publications/pdf/2019_07_ROSS.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2020).

- Reinhardt, W.; Schmidt, B.; Sloep, P.; Drachsler, H. Knowledge Worker Roles and Actions–Results of Two Empirical Studies. Knowl. Process Manag. 2011, 18, 150–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartkowiak, G. Employing knowledge workers 65 plus. In Perspective of Employees and Organizations; Vistula-Warsaw University Group: Warsaw, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bartkowiak, G. Best practices in the employment of knowledge workers 65 and over and the benefits of employing (an empirical approach). In Financial Environment and Business Development; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 463–471. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, B.R.; Slade, M.D.; Murphy, T.E.; Gill, T.M. Association between positive age stereotypes and recovery from disability in older persons. JAMA 2012, 308, 1972–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McHugh, K.E. Three faces of ageism: Society, image and place. Aging Soc. 2003, 23, 165–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozer, Z.C.; Terkes, N. Evaluation of nursing students’ towards ageism in Tourkey. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 11, 2512–2515. [Google Scholar]

- Vitman, A.; Iecovich, E.; Alfasi, N. Ageism and social integration of older adults in their neighborhoods in Israel. Gerontologist 2013, 54, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arani, M.M.; Azzami, S.; Azami, M.; Borji, M. Assessing attitudes toward alderly among nurses working in the city of IIam. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2017, 4, 311–313. [Google Scholar]

- Wethington, E.; Pillemer, K.; Principi, A. Research in Social Gerontology: Social Exclusion of Aging Adults. In Social Exclusion: Psychological Approaches to Understanding and Reducing Its Impact; Riva, P., Eck, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 177–195. [Google Scholar]

- King, B.J.; Roberts, T.J.; Bowers, B.J. Nursing student attitudes toward and preferences for working with older adults. Gerontol. Geriatr. Educ. 2013, 34, 272–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cybulski, M.; Krajewska-Kułak, E.; Jamiołkowski, J. Perception of the elderly by junior high school students and university students in Poland. Iran. J. Public Health 2015, 44, 580–582. [Google Scholar]

- Faronbi, J.O.; Adbowale, O.; Farnobi, G.O.; Musa, O.O.; Ayamolowo, S.J. Perception knowledge and attitude of Nursing students towards the care of older patients. Int. J. Afr. Nurs. Sci. 2017, 7, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, A.G.; Kulakçı Altınta, Ş.H.; Özen, Ç.İ.; Veren, F. Attitudes to aging and their relationship with quality of life in older adults in Turkey. Psychogeriatrics 2019, 19, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummert, M.L. A social cognitive perspective on age stereotypes. In Social Cognition and Aging; Hess, M., Blanschard-Fields, F., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999; pp. 175–196. [Google Scholar]

- Hummert, M.L.; Garstka, T.A.; Obrien, L.T.; Greenwald, A.G.; Mellot, D.S. Using the implicit association test to measure age differences in implicit social cognitions. Psychol. Aging 2002, 17, 482–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, M.B.; Dull, V.; Lui, L. Perceptions of the elderly: Stereotypes as prototypes. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1981, 41, 656–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, M.B.; Lui, L. Categorization of the elderly by the elderly: Effects of perceiver’s category membership. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1984, 10, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L. Attitudes towards aging and older people’s intentions to continue working: A Taiwanese study. Career Dev. Int. 2012, 17, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, S.T.; Cuddy, A.J.C.; Glick, P.; Xu, J. A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warm respectively from perceived status and competition. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 82, 878–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erber, J.T. Young and older adults appraisal of memory failures in young and older adult target persons. J. Gerontol. Psychol. Sci. 1989, 44, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwong See, S.T.; Heller, R.B. Judging older targets discourse: How do age stereotypes influence evaluation? Exp. Aging Res. 2004, 30, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biernat, M. Toward a broader view of social stereotyping. Am. Psychol. 2003, 58, 1019–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capowski, G. Ageism: The New diversity issue. Manag. Rev. 1994, 83, 48–65. [Google Scholar]

- See, S.T.K.; Hoffman, H.G.; Wood, T.L. Perception of old female eyewitness: Is it older eyewitness believable? Psychol. Aging 2001, 16, 346–350. [Google Scholar]

- Heckhausen, J.; Dixon, R.A.; Bales, P.B. Gains and losses in development Thrpoghout adulthood as perceived by different adult age groups. Dev. Psychol. 1989, 25, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slotterback, C.S.; Saarino, D.A. Attitudes toward older adults: Variation based on attitudinal task and attribute categories. Psychol. Aging 1996, 11, 563–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiske, S.T.; Taylor, S.E. Social Cognition, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Breckler, S. Empirical validation of affect, behavior, and cognition as distinct components of attitude. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1985, 47, 1191–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcıa-Santillan, A.; Moreno-Garcıa, E.; Carlos-Castro, J.; Zamudio-Abdal, J.H.; Õ-Trejo, J.G. Cognitive, Affective and Behavioral Components That Explain Attitude toward Statistic. J. Math. Res. 2012, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, B.R.; Banaji, M.R. Implicit ageism. In Ageism: Stereotyping and Prejudice Against Older Person; Nelson, T.D., Ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 49–75. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. Attitudes, Personality, and Behavior; Open University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Crano, W.D.; Gardikiotis, A. Attitude Formation and Change. In International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Wright, J.D., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; Volume 2, pp. 169–174. [Google Scholar]

- Kadefors, R.; Hanse, J.J. Employers Attitudes Toward Older Workers and Obstacles and Opportunities for the Older Unemployed to Reenter Working Life. Nord. J. Work. Life Stud. 2012, 2, 29–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dalen, H.P.; Henkens, K. Do stereotypes about older workers change? A panel study on changing attitudes of managers. Int. J. Manpow. 2019, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, P.H.; Tavernier, W.J.L.D.; Nielsen, P. To what extent are ageist attitudes among employers translated into discriminatory practices-the case of Denmark. Int. J. Manpow. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartkowiak, G.; Krugiełka, A. Possibilities of Improving Creative Thinking in Particularly Talented Employees, Outstanding Employee Teams and Management in the Organization, Scientific Paper No. 52: Organization and Management; Publishing House of Lodz University of Technology: Łódź, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Barabasz, A.; Wąsowicz, M. The image of knowledge workers 65 plus universities in the opinion of students. In Knowledge Workers 65 Plus-New Opportunities (or Controversies) in the Face of Contemporary Challenges; Vistula University: Warsaw, Poland, 2016; Volume 46. [Google Scholar]

- Bentley, T.A.; Teo, S.T.; Catley, B.; Blackwood, K.; Roche, M.M.; O’Driscol, M.P. Factors influencing leave intentions among older workers: A moderated-mediation model. Pers. Rev. 2019, 48, 898–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, K.; Sugisawa, H.; Sugihara, Y.; Shimmei, M. Perceived Age Discrimination and Job Satisfaction Among Older Employed Men in Japan. Int. J. Aging Hum. 2019, 89, 294–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egdell, V.; Maclean, G.; Raeside, R.; Chen, T. Age management in the workplace: Manager and older worker accounts of policy and practice. Ageing Soc. 2018, 40, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prislin, R. Attitude stability and attitude strength: One is enough to make it stable. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 26, 447–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazlagić, J. Creative in Business; Poltext: Warsaw, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hvide, H.K.; Kristiansen, E.G. Management of Knowledge Workers. Economics 2012, 55, 515–838. [Google Scholar]

- Drucker, P. Landmarks of Tomorrow; A Report of the New “Post–Modern Word; Transaction Publisher: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Toffler, A. Future Shock; Kurpisz Press: Poznan, Poland, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Mladkova, L. Management of Knowledge Workers. Econ. Manag. 2011, 16, 826–831. [Google Scholar]

- Davenport, T.H. Thinking for a Living: How to Get Better Performance and Results from Knowledge Workers; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kelemen, R.D. Globalizing European Union environmental policy. J. Eur. Public Policy 2010, 17, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mladkova, L.; Zauharova, J.; Novy, J. Motivation and Knowledge Workers. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 207, 768–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reboul, C.; Horel, G.; Krtousova, Z.; Lanthier, T.; Mutschlechner, E.; Pastia, D.; Royer, L.; Slota, J. Managing Knowledge Workers: The KWP Matrix. In Proceedings of the MOMAN 06, Prague, Czech Republic, 2 February 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bartkowiak, G. Corporate Social Responsibility in Theoretical and Empirical Aspects; Difin: Warsaw, Poland, 2011; p. 238. [Google Scholar]

- Kępiński, A. Rhythm of Life; PZWL: Warsaw, Poland, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Lewicka, M. Actor and observer. Psychological mechanisms of deviations from rationality in everyday thinking. In Polish Psychological Association; Publishing House: Olsztyn, Poland, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Goleman, D. Emotional Intelligence; Rebis: Poznań, Poland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zjawiona, K. Psychological Conditions of the Efficiency of Managing Employee Teams in Non-Profit Organizations. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Economics, Poznań, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zimbardo, P.G.; Gerrig, R.J. Psychology and Life; PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Victorino, C.A.; Nylund-Gibson, K.; Conley, S. Campus racial climate: A litmus test for faculty satisfaction at four-year colleges and universities. J. High. Educ. 2013, 84, 769–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matherne, C.F.; Ring, J.K.; Farmer, S. Organizational Moral Identity Centrality: Relationship with Citizenship Behaviors and Unethical Prosocial Behaviors. J. Bus. Psychol. 2018, 33, 711–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, C.I. The Function of the Executive; Harvard Univetsity Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, J.; Bolino, M.C.; Kelmen, T.K. Organizational Citizenship Behavior in the 21st Century: How Might Going. The Extra Mile Look Different at the Start of the New Millennium? Res. Pers. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 36, 51–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roethlisberger, F.J.; Dickson, W.J. Management and the Worker; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, D. The motivational basis of organizational behavior. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 1964, 9, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, D.W. A reappraisal and reinterpretation of the satisfaction-causes-performance hypothesis. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1977, 2, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, D.W. Organizational citizenship behavior: It’s construct clean-up time. Hum. Perform. 1997, 10, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, D.W. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Good Soldier Syndrome; Lexington Books: Lanham, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Paine, J.B.; Bachrach, B.G. Organizational behaviors: A critical review of the theoretical and empirical literature and suggestions for future research. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 513–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glińska–Neweś, A. Positive Interpersonal Relations in Management; Toruń University Press: Toruń, Poland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Grego-Planer, D. Organizational civic behavior and cooperation in a team-theoretical approach. In Scientific Notebooks of the Silesian University of Technology, Organization and Management; Silesian University of Technology Press: Gliwice, Poland, 2018; pp. 194–204. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, N.P.; Podsakoff, P.M.; Mackenzie, S.B.; Maynes, S.D.; Spoelma, T.M. Consequences of unit-level organizational citizenship behaviors: A review and recommendations for future research. J. Organ. Behav. 2014, 35, 87–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, D.W.; Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Its Nature, Antecedents, and Consequences; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bolino, M.C.; Hsiung, H.H.; Harvey, J.; Lepine, J.A. Well, i’m tired of tryin’! Organizational citizenship behavior and citizenship fatigue. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 56–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zalewska, A.M.; Krzywosz-Rynkiewicz, B. Psychological portraits of young poles. In Developmental and Subjective Conditions of Youth Civic Activity; SWPS Academica Publishing House: Warsaw, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chwalibóg, E. Triggering employee civic behavior as a step in the pursuit of organizational perfection. In Management Forum; Bełc, G., Kacała, J., Eds.; Scientific Work of the University of Economics: Wroclaw, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, L.J.; Anderson, S.E. Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.A.; Organ, D.W.; Near, J.P. Organizational citizenship behavior: Its nature and antecedents. J. Appl. Psychol. 1983, 68, 653–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homans, G.C. Basic social processes. In Contemporary Theories of Social Exchange; Kempny, M., Szmatka, J., Eds.; Polish Scientific Publishers PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Homans, G.C. Basic social processes. In Contemporary Sociological Theories; Jasińska-Kania, A., Nijakowski, L.M., Szacki, J., Ziółkowski, M., Eds.; Scholar Publishing House: Warsaw, Poland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Organ, D.W. The motivational basis of organizational citizenship behavior. Res. Organ. Behav. 1990, 12, 43–72. [Google Scholar]

- Bolino, M.C.; Turnley, W.H. Going to extra mile: Cultivating and managing employee citizenship behavior. Acad. Manag. Exec. 2003, 17, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diefendorff, J.M.; Brown, D.J.; Kamin, A.M.; Lord, R.G. Examining the roles of job involvement and work centrality in predicting organizational citizenship behaviors and job performance. J. Organ. Behav. 2002, 23, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LePine, J.A.; Erez, A.; Johnson, D.E. The nature and dimensionality of organizational citizenship behavior: A critical review and meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J.A.; Scott, B.A.; Rodell, J.B.; Long, D.M.; Zapata, C.P.; Conlon, D.E.; Wesson, M.J. Justice at the millennium, a decade later: A meta-analytic test of social exchange and affect-based perspectives. J. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 98, 199–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.N. Collective Dynamics of Citizenship Behaviour: What Group Characteristics Promote Group-Level Helping? J. Manag. Stud. 2009, 46, 1396–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, S.; Shi, J. Linking ethical leadership to employees’ organizational citizenship behavior: Testing the multilevel mediation role of organizational concern. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 141, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Moorman, R.H.; Fetter, R. Transformational leader behaviors and their effects on followers’ trust in leader, satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Leadersh. Q. 1990, 1, 107–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Law, K.S.; Hackett, R.D.; Wang, D.; Chen, Z.X. Leader-member exchange as a mediator of the relationship between transformational leadership and followers’ performance and organizational citizenship behavior. Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 420–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, N.P.; Whiting, S.W.; Podsakoff, P.M.; Blume, B.D. Individual-and organizational-level consequences of organizational citizenship behaviors: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 122–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeely, B.L.; Meglino, B.M. The role of dispositional and situational antecedents in prosocial organizational behavior: An examination of the intended beneficiaries of prosocial behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 1994, 79, 836–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penner, L.A.; Midili, A.R.; Kegelmeyer, J. Beyond job attitudes: A personality and social psychology perspective on the causes of organizational citizenship behavior. Hum. Perform. 1997, 10, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilies, R.; Fulmer, I.S.; Spitzmuller, M.; Johnson, M.D. Personality and citizenship behavior: The mediating role of job satisfaction. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 945–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorman, R.H.; Blakely, G.L. Individualism–collectivism as an individual difference predictor of organizational citizenship behavior. J. Organ. Behav. 1995, 16, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Allen, N.J. Organizational citizenship behavior and workplace deviance: The role of affect and cognitions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M.; Mayer, D.M. Good soldiers and good actors: Prosocial and impression management motives as interactive predictors of affiliative citizenship behaviors. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 900–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeuchi, R.; Bolino, M.C.; Lin, C.C. Too many motives? The interactive effects of multiple motives on organizational citizenship behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 1239–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewicka, M. Buy a book Mechanisms of civic activity of Poles. Psychol. Stud. 2004, 42, 65–82. [Google Scholar]

- Zając–Lamparska, L. Latent attitudes towards the elderly, manifested in three age groups: Early, middle and late adulthood. Dev. Psychol. 2008, 13, 91–102. [Google Scholar]

- Nolan, M.E.; Brown, J.; Davies, S.; Nolan, J.; Keady, J. The Senses Framework: Improving Care for Older People through A Relationship-Centred Approach; Getting Research into Practice (GRiP) Report No 2. Project Report; Sheffield Hallam University: Sheffield, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Whitney, R. Business Systems and Organization Capabilities: The Institutional Structuring of Competitive Competences; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Staudinger, U.M.; Bowen, C.E. A Syntetic approacg to aging in the work context. Res. Pap. 2011, 44, 295–306. [Google Scholar]

- Dul, J.; Ceylan, C.; Jaspers, F. Knowledge workers’ creativity and the role of the physical work environment. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2011, 50, 715–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, T.M. Factors Influencing Individual Creativity in the Workplace: An Examination of Quantitative Empirical Research. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2005, 7, 160–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, S.; Spector, P.E.; Goh, A.; Bruursema, K.; Kessler, S.R. The Deviant Citizen: Clarifying the Measurement of Organizational Citizenship Behavior and Its Relations to Counterproductive Work Behavior; Loyola University: Chicago, IL, USA, 2009; p. 85. [Google Scholar]

- Chwalibóg, E.M. Organizational Civic Behavior in the Context of Employee Engagement and Loyalty. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Economics in Wroclaw, Wrocław, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Moroń, M. Construction and empirical verification of the Prosocial Behavior Questionnaire (PBQ) and Paraproject Prosocial Trends Questionnaire (PKTP) for youth. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 7, 379–397. [Google Scholar]

- Rushton, J.; Chrishjohn, R.; Fekken, G. The altruistic personality and The Self-Report Altruism Scale. Personal. Individ. Differ. 1981, 2, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posthuma, R.A.; Wagstaff, M.F.; Campion, M.A. Age stereotypes and workplace age discrimination: A framework for future research. In Oxford Library of Psychology. The Oxford Handbook of Work and Aging; Hedge, J.W., Borman, W.C., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 298–312. [Google Scholar]

- Fazlagic, J. Creativity in the Education System; Bogucki Scientific Publishing House: Poznań, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Marin, B. Welfare in an Idle Society? Reinventing Retirement, Work, Wealth, Health, and Welfare; Ashgate: Vienna, Austria, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Krugiełka, A. CSR Modeling in the Internal Client Area; Poznan University of Technology: Poznań, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| Author(s) | Year of Publication | Type of Behavior within the OCB |

|---|---|---|

| Smith et al. | 1983 | Altruism (helping others) following procedures |

| Organ | 1988 | Altruism (helping others), diligence (being punctual and responsible). |

| Williams and Anderson | 1991 | Organizational behavior directed at the person—OCB-P; organizational behavior directed at the organization—OCB-O. |

| Van Dyne et al. | 1994 | Loyalty to the organization, organizational compliance (organizational compliance, acceptance and subordination to existing procedures and customs, social involvement, promoting the organization. |

| Moorman Blakely | 1995 | Helping others, taking individual initiatives, keeping employees’ commitments, punctuality; promoting organization outside. |

| Farth et al. | 1997 | Perseverance (good nature, dealing with inconveniences) courtesy, positive interpersonal relations, concern for the organization’s resources, identification with the organization (civic virtue) willingness to help others (altruism). |

| Podsakoff et al. | 2000 | Helping others, giving them support, sports behavior, interpersonal facilitation, involvement in work in the organization (civic virtue), expressing a positive opinion about the organization. |

| Coleman and Borman | 2000 | Helping colleagues, supporting the organization and caring for its good functioning, compliance with procedures and applicable rules. |

| Lewicka | 2004, 2005 | Activity resulting from a conscious and intentional analysis of the situation, which, apart from activities aimed at helping individuals, takes into account the group interest. |

| Grzelak | 2005 | Actions taken for people in need or supporting grassroots initiatives. |

| Skarżyńska | 2005 | Personality variable and voluntary activities and national attitude. |

| Radkiewicz, Skarżyńska | 2006, 2007 | Social activity focused on the interest of the group/society. |

| Zalewska, Krzywosz-Rynkiewicz | 2011 | The development perspective of increased activity is combined with the distinction of diverse civic activities in a passive, semiactive and active form. |

| Chwalibóg | 2013 | Social facilitation, supportive behavior, supporting others, OCB-1 behavior, motivated by altruism. |

| Dekas et al. | 2013 | Helping others, promoting organization, civic virtue, manifesting in commitment, social activity perceived as the ability to cooperate with people, promoting healthy behavior. |

| Klamut | 2013, 2015 | It includes four types of activity: Social activism (individual assistance to others, volunteering), supporting those in need, offering their own work. and time) social participation—cooperation with others (assistance groups, associations, NGOs), individual political activity (activities that increase the level of conscious understanding of reality socio-political political participation (impact on law and procedures of the state’s functioning |

| Harvey et al. | 2018 | Social trends that trigger civic behavior in the 21st century: Lower labor supply, globalization, migration and emigration, knowledge-based work of freelancers (freelancers), the need to manage employee diversity, diversity of values at work, technology development, and gaps in employee competence, employer’s brand. |

| Variable X and Y Variable | Correlations The Determined Correlation Coefficients Are Significant with p < 0.05000 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant: Y | Tilt: Y | Constant: X | Tilt: X | |

| Attitudes OCB-O 1 | 21.99151 | 0.934518 | −9.40214 | 0.697904 |

| Attitudes OCB-P 2 | 23.67901 | 0.696806 | −0.44616 | 0.492868 |

| Attitudes Pro-social behavior | 19.93809 | 0.501766 | 7.24226 | 0.345539 |

| Attitudes OCB | 94.79501 | 1.040357 | −2.42210 | 0.173367 |

| Variable X and Y Variable | Correlations The Determined Correlation Coefficients Are Significant with p < 0.05000 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | Standard Deviation | r(X,Y) | r2 | T | p | Important | |

| Attitudes OCB-O 1 | 37.9677 | 6.65689 | 0.807591 | 0.652204 | 13.06321 | 0.000000 | 93 |

| Attitudes OCB-P 2 | 35.5914 | 6.84016 | 0.586032 | 0.343433 | 6.89926 | 0.000000 | 93 |

| Attitudes Pro-social behavior | 28.5161 | 6.93230 | 0.416389 | 0.173380 | 4.36885 | 0.000033 | 93 |

| Attitudes OCB | 112.5806 | 14.09234 | 0.424693 | 0.180364 | 4.47492 | 0.000022 | 93 |

| Gender | Attitudes | OCB-O 1 | OCB-P 2 | Pro-Social Behavior | OCB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 755 | 1703 | 1726 | 1538 | 5170 |

| Male | 835 | 1828 | 1584 | 1114 | 6300 |

| Employment Sector | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitudes | OCB-O 1 | OCB-P 2 | Pro-Social Behavior | OCB | |

| Construction Sector | 215 | 455 | 423 | 305 | 1288 |

| Services sector | 221 | 438 | 426 | 371 | 1316 |

| Other sectors | 1154 | 2638 | 2461 | 1976 | 8866 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bartkowiak, G.; Krugiełka, A.; Dachowski, R.; Gałek, K.; Kostrzewa-Demczuk, P. Attitudes of Polish Entrepreneurs towards 65+ Knowledge Workers in the Context of Their Pro-Social Attitude and Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5294. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135294

Bartkowiak G, Krugiełka A, Dachowski R, Gałek K, Kostrzewa-Demczuk P. Attitudes of Polish Entrepreneurs towards 65+ Knowledge Workers in the Context of Their Pro-Social Attitude and Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Sustainability. 2020; 12(13):5294. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135294

Chicago/Turabian StyleBartkowiak, Grażyna, Agnieszka Krugiełka, Ryszard Dachowski, Katarzyna Gałek, and Paulina Kostrzewa-Demczuk. 2020. "Attitudes of Polish Entrepreneurs towards 65+ Knowledge Workers in the Context of Their Pro-Social Attitude and Organizational Citizenship Behavior" Sustainability 12, no. 13: 5294. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135294

APA StyleBartkowiak, G., Krugiełka, A., Dachowski, R., Gałek, K., & Kostrzewa-Demczuk, P. (2020). Attitudes of Polish Entrepreneurs towards 65+ Knowledge Workers in the Context of Their Pro-Social Attitude and Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Sustainability, 12(13), 5294. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135294