Sustainable Construction Investment, Real Estate Development, and COVID-19: A Review of Literature in the Field

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Climate change trends (the new technologies introduced reduce usage of materials, carbon emissions, etc.)

- Technological trends (digitization, smart amenities, increased use of technology by commercial real estate and accelerated adoption of digitally connected construction)

- Security trends (stronger cybersecurity measures)

- Economic trends (low interest rate, businesses faced with inequality, continuing issue of affordable housing, rise of alternative assets, lower demand for commercial office space, intra-regional investment, growing labor needs, rising material costs, and increased infrastructure spending)

- Social trends (remote worksites with mobile access and utility management for remote work)

- Demographic trends (continued population declines in major cities)

- Urban development trends (increased demand for suburban life, household consolidation, and ongoing “smart city” developments)

- Real estate trends (increased importance of rental property amenities, increased single-family rentals, focus on residential projects, changes in home ownership and customer-centric real estate)

- Construction trends (industry adaptability and resilience, increased use of offsite prefabrication, 3-D printing, increased focus on green building, modular and offsite construction, and greater priority for indoor air quality)

- Investment sustainability trends (environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG) criteria to generate long-term, competitive, financial returns and positive societal impact)

2. Methodology

- a search was done;

- a 3D CIRED map was created;

- CIRED-related papers printed in 2019–2020 and found by definite search keywords were compared;

- a 1st Hypothesis on the distribution and correlation of keywords was proposed;

- a colored document-frequency matrix was created;

- two more hypotheses (Hypotheses 2 and 3) were proposed, validated, and linked;

- micro-, meso-, and macro-level CIRED trends were established

3. Construction Investments during COVID-19

- The first important highlight is that the negative effects on investment caused by the COVID-19 shock have been neither as homogeneous nor as permanent as the 2018 financial shock, neither in sectorial data nor in geographical terms. The key reason for this is that machinery investment response has been more differentiated and dispersed and construction was not experiencing a previous boom this time.

- The response of construction investment has been more homogeneous, and it is also recovering faster so far than during the 2018 financial crisis shock. Facing a more negative situation prior to COVID-19 (as the construction industry was experiencing some de-leveraging consequences of the previous financial crisis), the initial response was homogeneous and amplified the already weak situation [62].

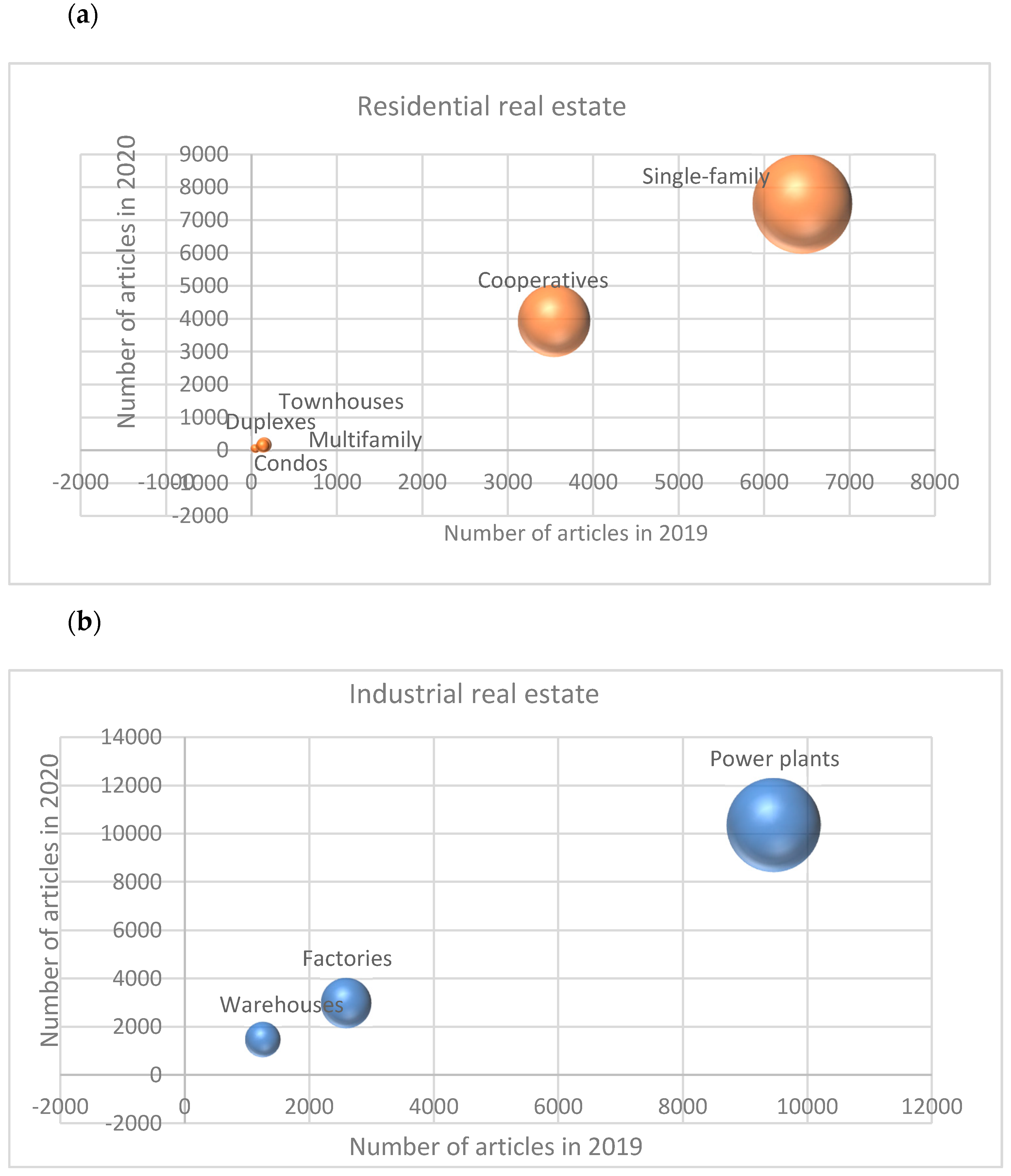

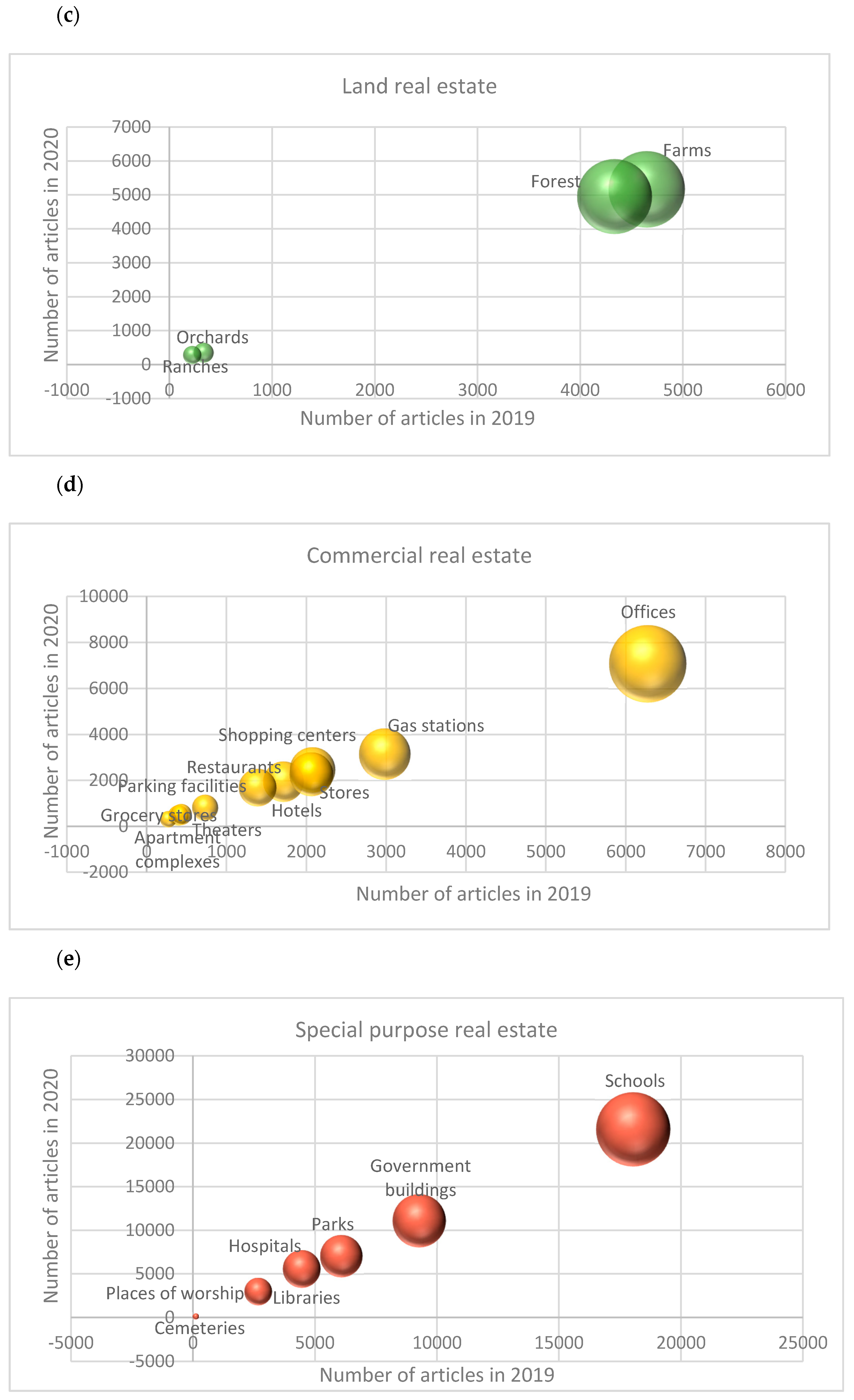

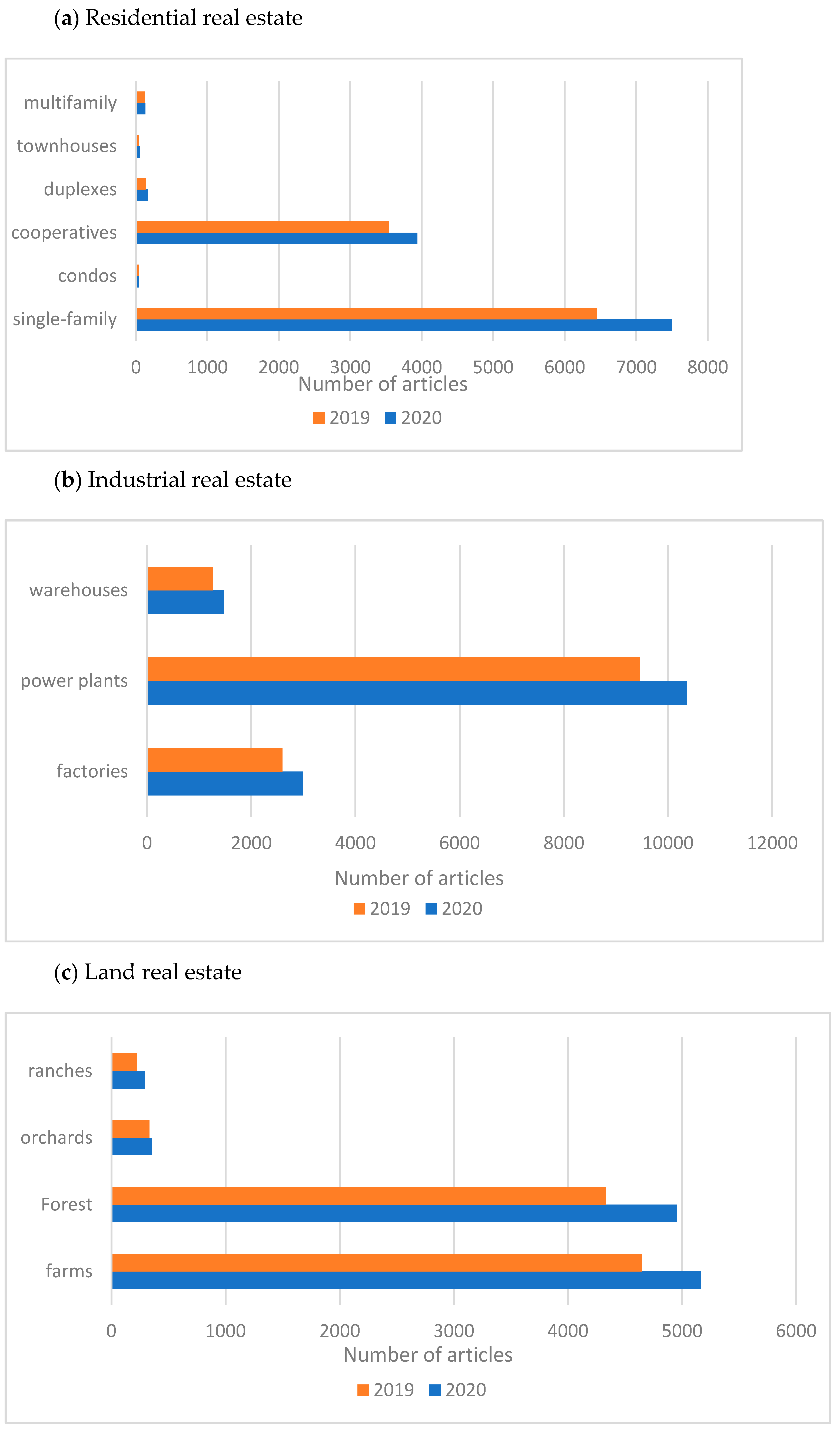

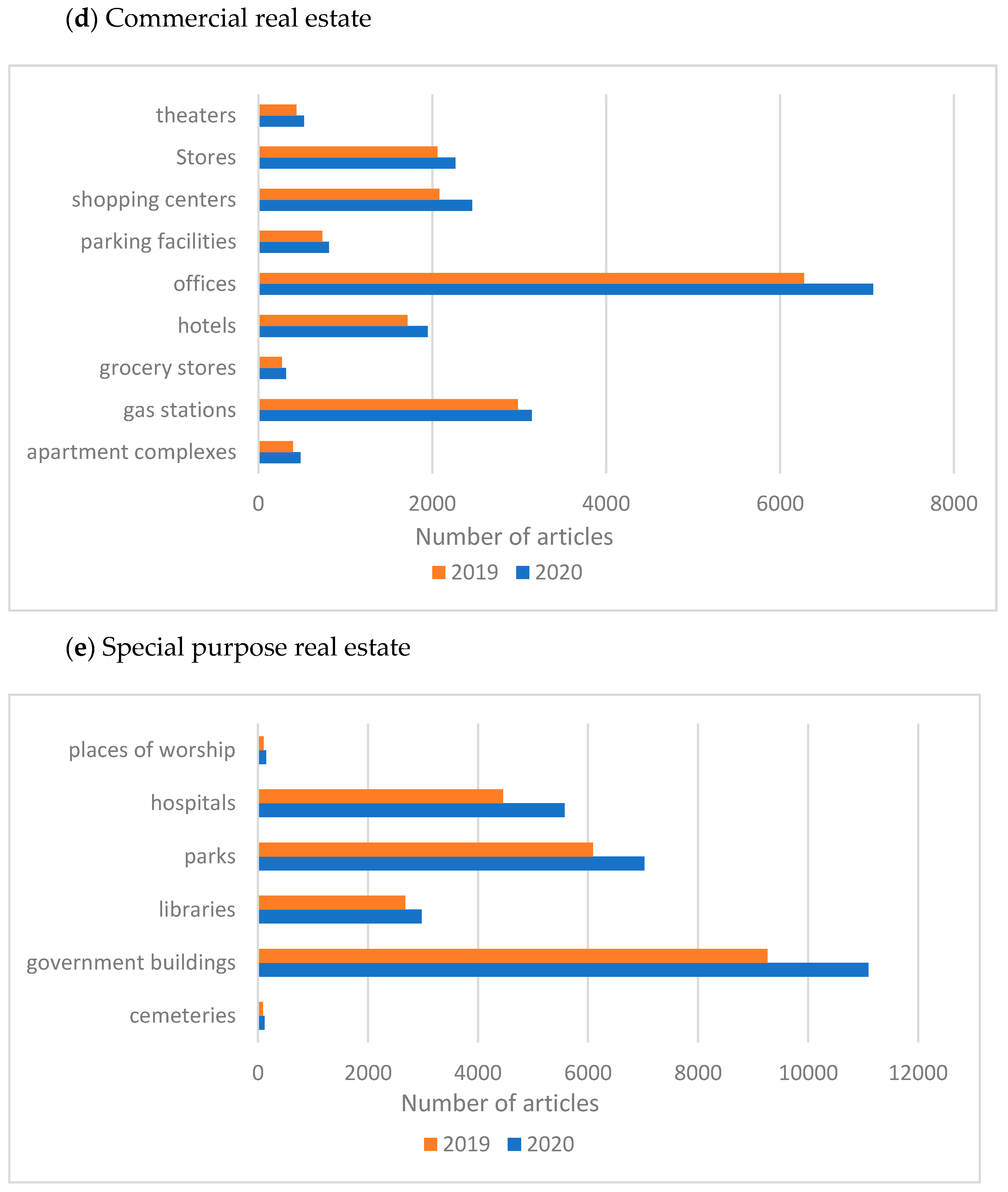

3.1. Property Types within Real Estate

3.2. Property Types within Real Estate

4. Real Estate Investment during COVID-19

4.1. Real Estate Operation

4.2. Accommodation Prices

4.3. Accommodation

4.4. Health Care

4.5. Offices

5. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Real Estate Industry

5.1. Guidelines for Real Estate Following the COVID-19 Pandemic

5.2. Real Estate Prices Change Guidelines

- The central bank policy is a quantitative stimulus causing people to protect their capital for fear of inflation thus preventing from a drop in real estate prices even in the case of recession.

- A decrease in mortgage interest rates, lack of alternative investments to capital gains, and a failure in pension reforms.

- Builders seek to sell their products to foundations and corporations thus leaving 20–30% of the supply of apartments in the sales market. Therefore, the supply of apartments to the general public will be reduced. The missing or urgently required products are expensive.

- A shortage of foreign labor in the construction industry is observed, and the situation will hardly change. On the condition that foreign staff are replaced with local employees, the work done will become more expensive, and the price for the results of this work will increase.

- The aftereffects of the pandemic have hindered ongoing construction and delayed the process of issuing building permits. Hence, the output of new construction will rise more slowly.

6. Global Construction and Real Estate Markets by Countries and New Shapes Focusing on Technology, Smart and Green Infrastructure Initiatives

6.1. Global Construction and Real Estate Markets by Countries

- The CRE sector suffered a heavy blow from the novel coronavirus crisis and possible structural shifts in demand add more uncertainty to the outlook for some of its segments. Enhanced supervisory attention is, therefore, warranted.

- Misaligned commercial real estate prices, especially with other vulnerabilities present, make the risk of lower future growth higher due to the likelihood of marked price corrections. Such corrections could hurt corporate investment and threaten financial stability. In this scenario, economic recovery would be hindered.

- Near-term policy support to stimulate aggregate demand and ensure the nonfinancial corporate sector access to loans will contribute positively to the recovery in the CRE sector.

- In the case of persisting large price misalignments, policymakers should move quickly to contain vulnerabilities in the sector with targeted macroprudential measures when required. Specific circumstances may also justify capital flow management measures to limit excessive cross-border inflows and the related potential risks.

6.2. Buildings Requiring New Shapes Focusing on Technology and Smart and Green Infrastructure Initiatives

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bansal, D.; Singh, R.; Sawhney, R.L. Effect of construction materials on embodied energy and cost of buildings—A case study of residential houses in India up to 60 m2 of plinth area. Energy Build. 2014, 69, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAuley, B.; Behan, A. Improving the Sustainability of the Built Environment by Training Its Workforce in More Efficient and Greener Ways of Designing and Constructing Through the Horizon 2020 BIMcert Project. 2019. Available online: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/schmuldistcon/28/ (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- Petri, I.; Kubicki, S.; Rezgui, Y.; Guerriero, A.; Li, H. Optimizing energy efficiency in operating built environment assets through building information modeling: A case study. Energies 2017, 10, 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garshasbi, S.; Santamouris, M. Using advanced thermochromic technologies in the built environment: Recent development and potential to decrease the energy consumption and fight urban overheating. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2019, 191, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The German Construction Industry must Act now to Gear Up for an Uncertain Future and be in a Position to Shape It Actively. Available online: https://www.rolandberger.com/en/Insights/Publications/What-the-new-normal-could-look-like-in-construction.html (accessed on 14 April 2021).

- General Economic Overview. Available online: https://fiec-statistical-report.eu/european-union (accessed on 5 February 2021).

- Short-Term Indicators Construction Industry. Deutsches Statistisches Bundesamt, 2021. Available online: https://www.destatis.de/EN/Themes/Economy/Short-Term-Indicators/Construction-Industry/pgw211.html (accessed on 5 February 2021).

- De Vet, J.M.; Nigohosyan, D.; Nunez Ferrer, J.; Gross, A.K.; Kuehl, S.; Flickenschild, M. Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on EU Industries. 2021. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2021/662903/IPOL_STU(2021)662903_EN.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2021).

- Impacto of COVID-19 Crisis on Construction. European Commission, 2021. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statisticsexplained/index.php?title=Impact_of_Covid-19_crisis_on_construction (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- Euroconstruct Issues Forecasts for 2021–2023. KHL, 2020. Available online: https://www.khl.com/1147226.article (accessed on 23 April 2021).

- Euroconstruct. Briefing on European Construction. August 2020. Available online: https://euroconstruct.org/ec/blog/2020_08 (accessed on 23 April 2021).

- Benson, A. Types of Real Estate Investments. 2021. Available online: https://www.nerdwallet.com/article/investing/types-of-real-estate-investments (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- Tian, L.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, B. Measuring residential and industrial land use mix in the peri-urban areas of China. Land Use Policy 2017, 69, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, G.B. How to Invest in Real Estate: 12 Types of Real Estate Investments. 2021. Available online: https://sparkrental.com/types-of-real-estate-investments/ (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- Lai, Y.; Chen, K.; Zhang, J.; Liu, F. Transformation of Industrial Land in Urban Renewal in Shenzhen, China. Land 2020, 9, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pina, R. How Do I Start Investing in Real Estate: A Step by Step Guide. 2021. Available online: https://www.themodestwallet.com/investing-in-real-estate/ (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- Ustaoglu, E.; e Silva, F.B.; Lavalle, C. Quantifying and modelling industrial and commercial land-use demand in France. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 22, 519–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Félix, J.; Castañón-Puga, M.; Gaxiola-Pacheco, C.G. Analyzing Urban Public Policies of the City of Ensenada in Mexico Using an Attractive Land Footprint Agent-Based Model. Sustainability 2021, 13, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojewnik-Filipkowska, A.; Rymarzak, M.; Lausberg, C. Current managerial topics in public real estate asset management. World Real Estate 2015, 4, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiei-Dastjerdi, H.; McArdle, G.; Matthews, S.A.; Keenan, P. Gap analysis in decision support systems for real-estate in the era of the digital earth. Int. J. Digital Earth 2020, 14, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kołodziejczyk, B.; Mielcar, P.; Osiichuk, D. The concept of the real estate portfolio matrix and its application for structural analysis of the Polish commercial real estate market. Econ. Res. Ekon. Istraživanja 2019, 32, 301–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C.; White, M. Challenging traditional real estate market classifications for investment diversification. J. Real Estate Portf. Manag. 2005, 11, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, M.; Bible, D. Classifications for commercial real estate. Apprais. J. 1992, 60, 237–246. [Google Scholar]

- Sehgal, S.; Upreti, M.; Pandey, P.; Bhatia, A. Real estate investment selection and empirical analysis of property prices: Study of select residential projects in Gurgaon, India. Int. Real Estate Rev. 2015, 18, 523–566. [Google Scholar]

- Hua, L. A comprehensive index model for real estate convenience based on multi-source data. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1865, 042142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, A.; Maan, V. A.; Maan, V. A Deep Learning-Based Segregation of Housing Image Data for Real Estate Application. In Congress on Intelligent Systems; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renigier-Biłozor, M.; Chmielewska, A. A rating system for the real estate market. Argum. Oeconomica 2019, 2, 427–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulsiri, N.; Vatananan-Thesenvitz, R. Improving systematic literature review with automation and bibliometrics. In Proceedings of the 2018 Portland International Conference on Management of Engineering and Technology (PICMET), Honolulu, HI, USA, 19–23 August 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daim, T.U.; Rueda, G.; Martin, H.; Gerdsri, P. Forecasting emerging technologies: Use of bibliometrics and patent analysis. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2006, 73, 981–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, A.; Watts, R. Using the PICMET Abstracts, 1997–2005. In VantagePoint Reader on your Conference CD: Tutorial. Portland International Conference on Management Engineering and Technology (PICMET’05). 2005. Available online: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.836.2789&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 25 February 2021).

- Porter, A.L. Mining PICMET: 1997–2003 Papers Help Track You Management of Technology Developments. 2003. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/1222794?denied= (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Pilkington, A. Technology commercialisation: Patent portfolio alignment and the fuel cell. In Proceedings of the PICMET’03: Portland International Conference on Management of Engineering and Technology Technology Management for Reshaping the World, Portland, OR, USA, 24–24 July 2003; pp. 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilkington, A.; Teichert, T. Conceptualizing the Field of Technology Management. In In Proceedings of the Portland International Conference on Management of Engineering and Technology; Available online: https://www.pomsmeetings.org/ConfProceedings/004/PAPERS/004-0186.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2021).

- Hood, W.W.; Wilson, C.S. The literature of bibliometrics, scientometrics, and informetrics. Scientometrics 2001, 52, 291–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thelwall, M.; Vaughan, L.; Björneborn, L. Webometrics. Ann. Rev. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2005, 39, 81–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björneborn, L.; Ingwersen, P. Toward a basic framework for webometrics. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2004, 55, 1216–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thelwall, M. Webometrics: Emergent or Doomed? Inf. Res. Int. Electron. J. 2010, 15, n4. [Google Scholar]

- Fenner, M. What can article-level metrics do for you? PLoS Biol 2013, 11, e1001687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tóth, I.; Lázár, Z.I.; Varga, L.; Járai-Szabó, F.; Papp, I.; Florian, R.V.; Ercsey-Ravasz, M. Mitigating ageing bias in article level metrics using citation network analysis. J. Informetr. 2021, 15, 101105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haustein, S. Grand challenges in altmetrics: Heterogeneity, data quality and dependencies. Scientometrics 2016, 108, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Priem, J. Altmetrics. Beyond Bibliometrics: Harnessing Multidimensional Indicators of Performance; Cronin, B., Sugimoto, C.R., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; pp. 263–287. [Google Scholar]

- Priem, J.; Taraborelli, D.; Groth, P.; Neylon, C. Altmetrics: A Manifesto. 2010. Available online: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1187&context=scholcom (accessed on 18 February 2021).

- Weller, K. Social Media and Altmetrics: An Overview of Current Alternative Approaches to Measuring Scholarly Impact. Incent. Perform. 2015, 261–276. Available online: https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2F978-3-319-09785-5_16.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2021).

- Qiu, J.; Zhao, R.; Yang, S.; Dong, K. Informetrics: Theory, Methods and Applications; Springer: Singapore, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Egghe, L. Expansion of the Field of Informetrics: Origins and Consequences. Inf. Process. Manag. 2005, 41, 1311–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guo, W.; Wu, S.; Wang, L.; Tan, T. Social-relational Topic Model for Social Networks. In Proceedings of the 24th ACM International on Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, 2015; pp. 1731–1734. Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.1145/2806416.2806611 (accessed on 14 March 2021).

- Rao, Y.; Li, Q.; Wenyin, L.; Wu, Q.; Quan, X. Affective topic model for social emotion detection. Neural Netw. 2014, 58, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vollset, S.E.; Goren, E.; Yuan, C.W.; Cao, J.; Smith, A.E.; Hsiao, T.; Bisignano, C.; Azhar, G.S.; Castro, E.; Chalek, J.; et al. Fertility, mortality, migration, and population scenarios for 195 countries and territories from 2017 to 2100: A forecasting analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 2020, 396, 1285–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeh, A.; Kissling, F.; Singer, P. Why sub-Saharan Africa might exceed its projected population size by 2100. Lancet 2020, 396, 1131–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.; Hu, S.; Xu, X.; Zhao, X.; Qiao, Y.; Broutet, N.; Canfell, K.; Hutubessy, R.; Zhao, F. Projections up to 2100 and a budget optimisation strategy towards cervical cancer elimination in China: A modelling study. Lancet Public Health 2019, 4, e462–e472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aletras, N.; Stevenson, M. Evaluating Topic Coherence Using Distributional Semantics. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Computational Semantics (IWCS), Potsdam, Germany, 19–22 March 2013; pp. 13–22. Available online: https://www.aclweb.org/anthology/W13-0102.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2021).

- Newman, D.; Lau, J.; Grieser, K.; Baldwin, T. Automatic evaluation of topic coherence. In Proceedings of the Human Language Technologies: The 2010 Annual Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2–4 June 2010; pp. 100–108. Available online: https://www.aclweb.org/anthology/N10-1012.pdf (accessed on 11 April 2021).

- Harris, Z.S. Distributional Structure. Word 1954, 10, 146–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Gerrish, S.; Wang, C.; Blei, D.M. Reading Tea Leaves: How Humans Interpret Topic Models. In Proceedings of the 23rd Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 7–10 December 2009; pp. 288–296. Available online: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.436.5683&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 21 February 2021).

- White, M.D.; Marsh, E.E. Content analysis: A flexible methodology. Libr. Trends 2006, 55, 22–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sonn, J.W.; Lee, J.K. The smart city as time-space cartographer in COVID-19 control: The South Korean strategy and democratic control of surveillance technology. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2020, 61, 482–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonn, J.W.; Kang, M.; Choi, Y. Smart city technologies for pandemic control without lockdown. Int. J. Urban Sci. 2020, 24, 149–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra-Vega, D. Lockdown, one, two, none, or smart. Modeling containing covid-19 infection. Concept. Model. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 730, 138917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Chong, Z. Smart City Projects Against COVID-19: Quantitative Evidence from China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 70, 102897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garel, A.; Petit-Romec, A. Investor rewards to environmental responsibility: Evidence from the COVID-19 crisis. J. Corp. Financ. 2021, 68, 101948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebekozien, A.; Aigbavboa, C. COVID-19 recovery for the Nigerian construction sites: The role of the fourth industrial revolution technologies. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 69, 102803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlas, A.B.; Castañeda, M.P.; Güler, S.; Orkun Isa, B.; Ortiz, A.; Salazar, S.A.; Rodrigo, T.; Vazquez, S. Big Data Analysis. Investment in Real Time and High Definition. Repositorio Comillas, 2020. Available online: https://repositorio.comillas.edu/xmlui/handle/11531/51161 (accessed on 22 January 2021).

- Understanding Real Estate Asset Classes and Property Types. Yieldstreet. 2021. Available online: https://www.yieldstreet.com/resources/article/understanding-real-estate-asset-classes-and-property-types (accessed on 17 March 2021).

- Dodge Momentum Index Increases in September. 2020. Available online: https://www.construction.com/news/dodge-momentum-index-increases-september-2020 (accessed on 16 March 2021).

- Sinai, T. Commercial Real Estate: What to Invest in Today. Wharton’s Real Estate Department, 28 September 2020. Available online: https://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article/commercial-real-estate-invest-today/ (accessed on 23 May 2021).

- WPS Insights: Demand for Office Space. How Will Covid-19 Change Demand for Office Space? 2021. Available online: https://www.wsp.com/en-GL/insights/how-will-covid-19-change-demand-for-office-space (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Karadima, S. Rethinking Office Space in a Post-Covid Environment. Investment Monitor. 2021. Available online: https://investmentmonitor.ai/it-outsourcing/rethinking-office-space-in-a-post-covid-environment (accessed on 17 March 2021).

- Roy, S.; Dutta, R.; Ghosh, P. Recreational and philanthropic sectors are the worst-hit US industries in the COVID-19 aftermath. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2021, 3, 100098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pancho Vallespin, B.E.; Lopez De Guzman, D.; Nayat Young, M. Analysis of US REIT Portfolio Performance on Pre and During COVID-19 Pandemic. In Proceedings of the 2021 The 2nd International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Industrial Management, 2021; pp. 25–31. Available online: https://covid19.elsevierpure.com/en/publications/analysis-of-us-reit-portfolio-performance-on-pre-and-during-covid (accessed on 23 March 2021).

- Nanda, A.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, F. How would the COVID-19 pandemic reshape retail real estate and high streets through acceleration of E-commerce and digitalization? J. Urban Manag. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagano, M.S.; Sedunov, J.; Velthuis, R. How did retail investors respond to the COVID-19 pandemic? The effect of Robinhood brokerage customers on market quality. Financ. Res. Lett. 2021, 101946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanrıvermiş, H. Possible impacts of COVID-19 outbreak on real estate sector and possible changes to adopt: A situation analysis and general assessment on Turkish perspective. J. Urban Manag. 2020, 9, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Giudice, V.; De Paola, P.; Del Giudice, F.P. COVID-19 infects real estate markets: Short and mid-run effects on housing prices in Campania region (Italy). Soc. Sci. 2020, 9, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, Q.; Sheng, X. Does Corporate Financialization Have a Non-Linear Impact on Sustainable Total Factor Productivity? Perspectives of Cash Holdings and Technical Innovation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushir, N.; Suryavanshi, R. Impact of COVID-19 on portfolio allocation decisions of individual investors. J. Pub. Aff. 2021, 13, e2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, H.V.; Mehdipanah, R.; Gullón, P.; Triguero-Mas, M. Breaking Down and Building Up: Gentrification, Its drivers, and Urban Health Inequality. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2021, 8, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoesli, M.; Malle, R. Commercial Real Estate Prices and Covid-19. Swiss Financ. Inst. Res. Pap. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.N.; Nguyen, T.L.; Dang, T.T. Analyzing operational efficiency in real estate companies: An application of GM (1, 1) And DEA malmquist model. Mathematics 2021, 9, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, K.S.; Yiu, C.Y.; Xiong, C. Housing Market in the Time of Pandemic: A Price Gradient Analysis from the COVID-19 Epicentre in China. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2021, 14, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Qiu, S.; Zhang, G. The impact of COVID-19 on housing price: Evidence from China. Financ. Res. Lett. 2021, 101944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Toro, P.; Nocca, F.; Buglione, F. Real Estate Market Responses to the COVID-19 Crisis: Which Prospects for the Metropolitan Area of Naples (Italy)? Urban Sci. 2021, 5, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakeley, G. Financialization, real estate and COVID-19 in the UK. Community Dev. J. 2021, 56, 79–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silow-Carroll, S.H.A.R.O.N.; Peartree, D.; Tucker, S.; Pham, A. Evidence on Single-Resident Rooms to Improve Personal Experience and Public Health. Health Management Associates, 2021. Available online: https://www.healthmanagement.com/wp-content/uploads/HMA.Single-Resident-Rooms-3.22.2021_final.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Tan, Z.; Zheng, S.; Palacios, J.; Hooks, C. Market Adoption of Healthy Buildings in the Office Sector: A Global Study from the Owner’s Perspective. MIT Center for Real Estate Research Paper, (21/07). 2021. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3784793 (accessed on 17 April 2021).

- Diming, C.; Harris, R.; Kane, C.; Luff, M.; Muir, G.; Rischbieth, A.; Semple, E.; Todorova, A.; Waters, C.; Anastassiou, E. Fresh perspectives on the future of the office: A way forward. Corp. Real Estate J. 2021, 10, 271–284. [Google Scholar]

- Billio, M.; Varotto, S. A New World Post COVID-19: Lessons for Business, the Finance Industry and Policy Makers; Venezia Edizioni Ca’Foscari-Digital Publishing: Venezia, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójcik, D.; Ioannou, S. COVID-19 and Finance: Market Developments So Far and Potential Impacts on the Financial Sector and Centres. Tijdschr. Voor Econ. En Soc. Geogr. 2020, 111, 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francke, M.; Korevaar, M. Housing markets in a pandemic: Evidence from historical outbreaks. J. Urban Econ. 2021, 123, 103333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Wang, Y.; Xu, A.; Xia, N.; Yao, T. The COVID-19 Effect on Chinese Real Estate Market. Front. Econ. Manag. 2021, 2, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanović-Milenković, M.; Đurković, A.; Vučetić, D.; Drašković, B. The impact of covid-19 pandemic on the real estate market development projects. Eur. Proj. Manag. J. 2020, 10, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicola, M.; Alsafi, Z.; Sohrabi, C.; Kerwan, A.; Al-Jabir, A.; Iosifidis, C.; Agha, M.; Agha, R. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): A review. Int. J. Surg. 2020, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marona, B.; Tomal, M. The COVID-19 pandemic impact upon housing brokers’ workflow and their clients’ attitude: Real estate market in Krakow. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2020, 8, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Peeters, J.; Mittal, V.; Van Nieuwerburgh, S. Flattening the Curve: Pandemic-Induced Revaluation of Urban Real Estate. SSRN Electron. J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, S.; Nanda, A.; Thanos, S.; Valtonen, E.; Xu, Y. Imagining a post-COVID-19 world of real estate. Town Plan. Rev. 2021, 92, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R.W. Post-pandemic consumption: Portal to a new world? Cad. EBAPE BR 2020, 18, 639–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’alessandro, D.; Gola, M.; Appolloni, L.; Dettori, M.; Fara, G.M.; Rebecchi, A.; Settimo, G.; Capolongo, S. COVID-19 and living space challenge. Well-being and public health recommendations for a healthy, safe, and sustainable housing. Acta Biomedica 2020, 91, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, N. Economic Effects of Coronavirus Outbreak (COVID-19) on the World Economy. IESE Business School Working Paper No. WP-1240-E 2020. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3557504 (accessed on 19 March 2021).

- Dolnicar, S.; Zare, S. COVID19 and Airbnb—Disrupting the Disruptor. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 83, 102961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barua, S. Understanding Coronanomics: The Economic Implications of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic. SSRN Electron. J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balemi, N.; Füss, R.; Weigand, A. COVID-19’s impact on real estate markets: Review and outlook. Financ. Mark. Portf. Manag. 2021, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujral, V.; Palter, R.; Sanghvi, A.; Vickery, B. Commercial Real Estate must Do More than Merely Adapt to Coronavirus. McKinsey & Company. Private Equity & Principal Investors Practice. 2020. Available online: https://magnify.partners/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Commercial-real-estate-must-do-more-than-merely-adapt-to-coronavirus.pdf (accessed on 13 March 2021).

- Awada, M.; Becerik-Gerber, B.; Hoque, S.; O’Neill, Z.; Pedrielli, G.; Wen, J.; Wu, T. Ten questions concerning occupant health in buildings during normal operations and extreme events including the COVID-19 pandemic. Build. Environ. 2021, 188, 107480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyedeji, J.O. The Impact of COVID-19 on Real Estate Transaction in Lagos, Nigeria. Int. J. Real Estate Stud. INTREST 2020, 14, 107–112. [Google Scholar]

- Apergis, N. The role of housing market in the effectiveness of monetary policy over the Covid-19 era. Econ. Lett. 2021, 200, 109749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hromada, E. Impacts of COVID-19 on the Real Estate Market in the Czech Republic; Impacts of COVID-19 on the Real Estate Market in the Czech Republic. SHS Web Conf. 2021, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Real Capital Analytics. Global Commercial Real Estate Sales Fall Back in Q1. 2021. Available online: https://www.rcanalytics.com/gct-overview-q1-2021/ (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Fendoglu, S.; Gan, Z.K.; Khadarina, O.; Mok, J.; Qureshi, M.; Vandenbussche, J. Commercial Real Estate. Financial Stability Risks during the Covid-19 Crisis and Beyond. International Monetary Fund, 2021. Available online: https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/books/082/29631-9781513569673-en/ch03.xml (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Mundra, N.; Mishra, R.P. Business Sustainability in Post COVID-19 Era by Integrated LSS-AM Model in Manufacturing: A Structural Equation Modeling. Procedia CIRP 2021, 98, 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gornig, M.; Michelsen, C.; Pagenhardt, L. German construction industry remains on its path of growth during the coronavirus recession. DIW Wkly. Rep. 2021, 11, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gittelsohn, J. Warehouses Lure More Cash Than Offices in Pandemic-Fueled Flip. 2020. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-12-10/warehouses-lure-more-cash-than-offices-in-pandemic-fueled-flip (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Ling, D.C.; Wang, C.; Zhou, T. A first look at the impact of COVID-19 on commercial real estate prices: Asset-level evidence. Rev. Asset Pricing Stud. 2020, 10, 669–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodeur, A.; Gray, D.; Islam, A.; Bhuiyan, S. A literature review of the economics of COVID-19. J. Econ. Surv. 2021, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UBS. Real Estate Outlook—Edition 1. 2021. Available online: https://www.ubs.com/global/en/asset-management/insights/asset-class-research/real-assets/2021/real-estate-outlook-edition-1.html (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Ding, W.; Levine, R.; Lin, C.; Xie, W. Corporate immunity to the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Financ. Econ. 2021, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, S. Hotel, Retail Sectors Hit ‘Hard’ by Distress in Q2—RCA. 2020. Available online: https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/news-insights/latest-news-headlines/hotel-retail-sectors-hit-hard-by-distress-in-q2-8211-rca-59543058 (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Ademmer, M.; Boysen-Hogrefe, J.; Fiedler, S.; Groll, D.; Jannsen, N.; Kooths, S.; Meuchelböck, S. German Economy Winter 2020-Second Covid Wave Interrupts Recovery. Kiel Institute Economic Outlook No. 74. 2020. Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/229943 (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Real Estate. China Property Investment Falls 16.3%, Sales Plunge by 40%. The Business Times, March 2020. Available online: https://www.businesstimes.com.sg/real-estate/china-propertyinvestment-%falls-163-sales-plunge-by-40(accessed on 3 May 2021).

- GlobalData. GlobalData Sharply Revises Down Forecast for Construction Output Growth Globally to Just 0.5% in 2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.globaldata.com/globaldata-sharply-revisesdown-forecast-for%-construction-output-growth-globally-to-just-0-5-in2020/ (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Lanjing Finance. Fosun and China Lodging’s Hotels Accelerate Their Opening, the Hotel Industry Welcomes the Spring. 2020. Available online: https://www.lanjinger.com/d/134550 (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Qu, X. Qiu You: After the Oandemic, Investors will Prefer’ Small and Refined’ Mid-Range Hotels. 2020. Available online: http://www.bjnews.com.cn/feature/2020/04/22/719693.html (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Gallen, S. The Response of Tourism Businesses vis-à-vis the Economic Ramifications of SARS-CoV-2. 2020. Available online: https://www.aiest.org/news/ (accessed on 27 April 2021).

- Hao, F.; Xiao, Q.; Chon, K. COVID-19 and China’s hotel industry: Impacts, a disaster management framework, and post-pandemic agenda. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 90, 102636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KPMG. COVID-19: Assessment of Economic Impact on Construction Sector in India. 2020. Available online: https://home.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/in/pdf/2020/05/covid-19-assessment-economic-impact-construction-sector.pdf? (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Majumder, S.; Biswas, D. COVID-19 Impacts Construction Industry: Now, then and Future. In COVID-19: Prediction, Decision-Making, and Its Impacts; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geary, R.S.; Wheeler, B.; Lovell, R.; Jepson, R.; Hunter, R.; Rodgers, S. A call to action: Improving urban green spaces to reduce health inequalities exacerbated by COVID-19. Prev. Med. 2021, 145, 106425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Energy Agency. Global Energy Review 2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-energy-review-2020 (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Helm, D. The environmental impacts of the coronavirus. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2020, 76, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vis, P. Planting the Seeds of a Green Economic Recovery after COVID-19. 2020. Available online: https://www.euractiv.com/section/energy-environment/opinion/planting-the-seeds-of-a-green-economic-recovery-after-covid-19/ (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Lahcen, B.; Brusselaers, J.; Vrancken, K.; Dams, Y.; Paes, C.D.S.; Eyckmans, J.; Rousseau, S. Green recovery policies for the COVID-19 crisis: Modelling the Impact on the economy and greenhouse gas emissions. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2020, 76, 731–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ASCE. Civil Engineers Outline Most Pressing Infrastructure Priorities for Covid-19 Relief. 2020. Available online: https://www.asce.org/templates/official-statement-detail.aspx?id=36882 (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- America’s Infrastructure Report Card. New Study: U.S. Mayors Prioritize Infrastructure Investment to Drive Post-COVID-19 Economic Recovery. 2020. Available online: https://infrastructurereportcard.org/new-study-u-s-mayors-prioritize-infrastructure-investment-to-drive-post-covid-19-economic-recovery/ (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Mance, H. The Rise and Fall of the Office. The Financial Times, 2020. Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/f43b8212-950a-11ea-af4b-499244625ac4(accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Tranel, B. How should Office Buildings Change in a Post-Pandemic World? Gensler, 2020. Available online: https://www.gensler.com/research-insight/blog/how-should-office-buildings-change-in-a-post-pandemic-world (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Diemar, E.L. No One will Mourn the End of Hot Desking. The Australian Human Resources Institute, 2020. Available online: https://www.hrmonline.com.au/research/the-end-of-hot-desking/ (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Coleman, C.; Ricker, D.; Stull, J. 10 Considerations for Transitioning back to Work in a postCOVID-19 World. Gensler, 2020. Available online: https://www.gensler.com/research-insight/blog/10-considerations-for-transitioning-back-to-work-in-a-post (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Taylor, A. Hot Desking Is Dead: Why Workers can Refuse to Return to the Office. The Age, 2020. Available online: https://www.theage.com.au/business/workplace/hot-desking-is-dead-why-workerscan-refuse-to-return-to-the-office-20200515-p54thr.html(accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Cummions, C.; Johanson, S. Return to the Office a Whole New Ball Game: Bring in the COVID Captain. The Age, 2020. Available online: http://www.theage.com.au/business/property/return-tothe-office-a-whole-new-ball-game-bring-in-the-covid-captain-20200504-p54pn6.html?btis(accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Morrison, R. Goodbye to the Crowded Office: How Coronavirus will Change the Way We Work Together. The Conversation, 2020. Available online: https://theconversation.com/goodbye-to-the-crowdedoffice-how-coronavirus-will-change-the-way-we-work-together-137382 (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Bleby, M. New Digs: PwC Copies Airline Lounges, Hotels for New Melbourne Office Digs. 2020. Available online: https://www.afr.com/real-estate/commercial/development/new-digs-pwc-copies-airline-loungeshotels-for-new-melbourne-office-digs-20161215-gtc149 (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Margolies, J. What will Tomorrow’s Workplace Bring? More Elbow Room for Starters. The Age, 2020. Available online: http://www.theage.com.au/business/workplace-relations/what-will-tomorrow-s-wo(accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Carmichael, S.G. Open Plan Offices will Survive this Pandemic. Here’s Why. The Sydney Morning Herald. 2020. Available online: https://www.smh.com.au/business/workplace/openplan-offices-will-survive-this-pandemic-here-s-why-20200514-p54st6.html (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Wainwright, O. Smart Lifts, Lonely Workers, no Towers or Tourists: Architecture after Coronavirus. The Guardian, 2020. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2020/apr/13/smart-lifts-lonely-workers-no-towers-architecture-after-covid-19-coronavirus (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Kretchmer, H. 10 Ways COVID-19 could Change Office Design. World Economic Forum, 2020. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/04/covid19-coronavirus-change-office-work-homeworking-remote-design/ (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Milota, C. A Common Sense Guide for Returning to the Post COVID-19 Workplace. Workdesign Magazine. 2020. Available online: https://www.workdesign.com/2020/04/a-common-senseguide-for-the-return-to-the-office/ (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Short, S. How COVID-19 is Changing the Office. 2020. Available online: https://go.ey.com/3avJ1hf (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Parker, L.D. The COVID-19 Office in Transition: Cost, Efficiency and the Social Responsibility Business Case. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2020, 33, 1943–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batty, M. The coronavirus crisis: What will the post-pandemic city look like? Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2020, 47, 547–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlfeldt, G.M.; Wendland, N. Fifty years of urban accessibility: The impact of the urban railway network on the land gradient in Berlin 1890–1936. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2011, 41, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lertpalangsunti, N.; Chan, C.W. An architectural framework for the construction of hybrid intelligent forecasting systems: Application for electricity demand prediction. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 1998, 11, 549–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaklauskas, A.; Zavadskas, E.K.; Trinkunas, V. A multiple criteria decision support on-line system for construction. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2007, 20, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MoneyContro. Coronavirus-Construction Sector Facing Daily Loss of Rs. 30,000 Crore Investments in Projects to Fall 13–30%: KPMG. Available online: https://www.moneycontrol.com/news/real-estate-2/coronavirus-construction-sector-facing-daily-loss-of-rs-30000-crore-investments-in-projects-to-fall-13-30-kpmg-5243761.html (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Banaitiene, N.; Banaitis, A. Risk management in construction projects. Risk Management–Current Issues and Challenges. In Risk Management–Current Issues and Challenges; Banaitiene, N., Ed.; VDOC.PUB: London, UK, 2012; pp. 429–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lamper, M.; Inglehart, R.; Metaal, S.; Schoemaker, H.; Papadongonas, P. Covid (2021) Pandemic Ignites Fear, but Boosts Progressive Ideals and Calls for Inclusive Economic Growth, Measuring the Pandemic’s Impact on Social Values, Emotions and Priorities in 24 Countries. Glocalities, 2021. Available online: https://glocalities.com/latest/reports/valuestrends (accessed on 14 March 2021).

- Mongeon, P.; Paul-Hus, A. The journal coverage of bibliometric databases: A comparison of Scopus and Web of Science. Scientometrics 2016, 106, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, D.; Wang, J. Coverage and overlap of the new social sciences and humanities journal lists. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2011, 62, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Gómez, A. Bibliometrics as a tool to map uncharted territory: A study on non-professional interpreting. Perspectives 2015, 23, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pech, G.; Delgado, C. Screening the most highly cited papers in longitudinal bibliometric studies and systematic literature reviews of a research field or journal: Widespread used metrics vs. a percentile citation-based approach. J. Informetr. 2021, 15, 101161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardi, A.; Kodonas, K.; Lillis, T.; Veis, A. Top-Cited Articles in Implant Dentistry. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2017, 32, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Baldiotti, A.L.P.; Amaral-Freitas, G.; Barcelos, J.F.; Freire-Maia, J.; de França Perazzo, M.; Freire-Maia, F.B.; Paiva, S.M.; Ferreira, F.M.; Martins-Júnior, P.A. The Top 100 Most-Cited Papers in Cariology: A Bibliometric Analysis. Caries Res. 2020, 18, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakkalbasi, N.; Bauer, K.; Glover, J.; Wang, L. Three options for citation tracking: Google Scholar, Scopus and Web of Science. Biomed. Digit. Libr. 2006, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Falagas, M.E.; Pitsouni, E.I.; Malietzis, G.A.; Pappas, G. Comparison of PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar: Strengths and weaknesses. FASEB J. 2007, 22, 338–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harzing, A.-W.K.; Van der Wal, R. Google Scholar as a new source for citation analysis. Ethics Sci. Environ. Politics 2008, 8, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, P.; Asif, J.A.; Alam, M.K.; Slots, J. A bibliometric analysis of Periodontology 2000. Periodontology 2020, 82, 286–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaklauskas, A.; Herrera-Viedma, E.; Echenique, V.; Zavadskas, E.K.; Ubarte, I.; Mostert, A.; Podvezko, V.; Binkyte, A.; Podviezko, A. Multiple criteria analysis of environmental sustainability and quality of life in post-Soviet states. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 89, 781–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaklauskas, A.; Dias, W.P.; Binkyte-Veliene, A.; Abraham, A.; Ubarte, I.; Randil, O.P.; Siriwardana, C.S.; Lill, I.; Milevicius, V.; Podviezko, A.; et al. Are environmental sustainability and happiness the keys to prosperity in Asian nations? Ecol. Indic. 2020, 119, 106562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaklauskas, A.; Abraham, A.; Milevicius, V. Diurnal emotions, valence and the coronavirus lockdown analysis in public spaces. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2021, 98, 104122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaklauskas, A.; Bardauskiene, D.; Cerkauskiene, R.; Ubarte, I.; Raslanas, S.; Radvile, E.; Kaklauskaite, U.; Kaklauskiene, L. Emotions analysis in public spaces for urban planning. Land Use Policy 2021, 107, 105458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Residential Real Estate | Commercial Real Estate | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Family | Cooperatives | Apartment Complexes | Gas Stations | Grocery Stores | Hotels | Offices | Parking Facilities | Restaurants | Shopping Centers | Stores | Theatres | |

| single-family | 1 | 0.998857609 | 0.99388799 | 0.954403551 | 0.954403551 | 0.993192574 | 0.993628616 | 0.97575933 | 0.983551995 | 0.993653389 | 0.994720214 | 0.913005767 |

| cooperatives | 1 | 0.993160446 | 0.984543879 | 0.960366376 | 0.993459236 | 0.991286491 | 0.978740358 | 0.985521474 | 0.995148577 | 0.996037263 | 0.909229002 | |

| apartment complexes | 1 | 0.98971233 | 0.957624301 | 0.984941956 | 0.982602524 | 0.984506485 | 0.978254443 | 0.992578623 | 0.988343034 | 0.881230379 | ||

| gas stations | 1 | 0.940822182 | 0.967460598 | 0.977432403 | 0.978857917 | 0.964507344 | 0.981760469 | 0.980088551 | 0.840560341 | |||

| grocery stores | 1 | 0.963407374 | 0.923667713 | 0.977025896 | 0.981813038 | 0.972979144 | 0.972010935 | 0.854483561 | ||||

| hotels | 1 | 0.985424609 | 0.973953815 | 0.987543981 | 0.991298056 | 0.993004255 | 0.928051521 | |||||

| offices | 1 | 0.954977303 | 0.963859502 | 0.980842839 | 0.982675265 | 0.916196969 | ||||||

| parking facilities | 1 | 0.982824235 | 0.986497721 | 0.979963454 | 0.852731323 | |||||||

| restaurants | 1 | 0.988855726 | 0.98932029 | 0.89865398 | ||||||||

| shopping centers | 1 | 0.994105605 | 0.894033416 | |||||||||

| stores | 1 | 0.905889551 | ||||||||||

| theaters | 1 | |||||||||||

| Residential Real Estate | Commercial Real Estate | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Single-family | Cooperatives | Duplexes | Apartment complexes | Gas stations | Grocery stores | Hotels | Offices | Parking facilities | Restaurants | Shopping centers | Stores | Theaters |

| Web of Science results: | |||||||||||||

| Total Publications | 66 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 23 | 175 | 3 | 6 | 23 | 19 | - |

| h-index | 18 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 23 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 5 | - |

| Average citations per item | 17.32 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 8.39 | 11.8 | 0.67 | 13.5 | 5.13 | 5.05 | - |

| Sum of Times Cited | 1143 | 72 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 193 | 2065 | 2 | 81 | 118 | 96 | - |

| Scholar results | 70,100 | 48,100 | 13,600 | 43,600 | 146,00 | 61,100 | 156,00 | 419,00 | 82,500 | 152,000 | 163,000 | 264,000 | 54,200 |

| Wikipedia, mln. | 37.5 | 3.2 | 0.684 | 204 | 33 | 272 | 22.9 | 38.9 | 59.4 | 21.6 | 54.8 | 864 | 42.2 |

| Facebook, mln. | 94.4 | 43.7 | 39.9 | 909 | 183 | 254 | 70.7 | 180 | 159 | 123 | 279 | 1560 | 11.8 |

| Twitter, mln. | 123 | 17.3 | 17.9 | 615 | 99.5 | 140 | 68.6 | 163 | 256 | 129 | 151 | 1330 | 12.2 |

| Scienceblogs | 41,000 | 8 | 24,700 | 8 | 8 | 145,000 | 8 | 22,000 | 23,400 | 67,600 | 27,900 | 108,00 | 52,200 |

| Positive Google search results, mln. | 169 | 15.3 | 4.22 | 350 | 84.8 | 55.6 | 20.5 | 337 | 151 | 69.6 | 405 | 348 | 64.9 |

| Negative Google search results, mln. | 45.5 | 10.2 | 2.11 | 206 | 71.4 | 34.3 | 16.3 | 324 | 76.7 | 45.3 | 173 | 155 | 52.1 |

| Positive Yandex search results, mln. | 7 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 8 | 6 |

| Negative Yandex search results, mln. | 6 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 9 | 8 | 6 |

| Positive Yahoo search results, mln. | 80.5 | 86.7 | 81.1 | 1.6 | 8.95 | 18.9 | 187 | 317 | 121 | 179 | 20.1 | 223 | 112 |

| Negative Yahoo search results, mln. | 64.7 | 68.2 | 64 | 1.6 | 7.64 | 17.1 | 175 | 296 | 106 | 168 | 16.2 | 210 | 93.7 |

| Positive Bing search results, mln. | 0.109 | 47.2 | 11.2 | 16.6 | 7.11 | 8.81 | 30.9 | 48.6 | 15.3 | 55.2 | 66.2 | 74.6 | 17.6 |

| Negative Bing search results, mln. | 0.862 | 20.3 | 16.9 | 15.5 | 50.9 | 55.5 | 48.4 | 60.1 | 20.2 | 58.8 | 16.4 | 137 | 26.8 |

| 2020 | 7499 | 3936 | 170 | 483 | 3146 | 317 | 1945 | 7072 | 809 | 1686 | 2458 | 2266 | 522 |

| 2019 | 6449 | 3541 | 141 | 395 | 2983 | 270 | 1715 | 6276 | 733 | 1387 | 2082 | 2060 | 435 |

| 2018 | 6040 | 3282 | 152 | 380 | 2838 | 226 | 1480 | 6061 | 584 | 1239 | 1920 | 1812 | 391 |

| 2017 | 5836 | 3076 | 159 | 371 | 2923 | 176 | 1475 | 6275 | 572 | 1095 | 1848 | 1712 | 371 |

| 2016 | 5289 | 2909 | 134 | 321 | 2291 | 182 | 1420 | 5730 | 572 | 1141 | 1671 | 1507 | 412 |

| 2015 | 5045 | 2779 | 113 | 273 | 2006 | 186 | 1376 | 5518 | 395 | 1045 | 1572 | 1533 | 405 |

| 2014 | 4456 | 2521 | 123 | 232 | 1993 | 151 | 1203 | 5037 | 385 | 948 | 1444 | 1402 | 327 |

| 2013 | 4091 | 2324 | 99 | 227 | 1763 | 125 | 1055 | 4538 | 344 | 863 | 1285 | 1251 | 314 |

| 2012 | 3553 | 2080 | 105 | 216 | 1415 | 108 | 1024 | 3889 | 282 | 703 | 1170 | 1073 | 307 |

| 2011 | 3267 | 1782 | 89 | 159 | 1258 | 90 | 922 | 3625 | 240 | 721 | 992 | 942 | 320 |

| 2010 | 2849 | 1716 | 92 | 129 | 1049 | 100 | 771 | 3257 | 210 | 611 | 951 | 902 | 358 |

| 2009 | 2662 | 1610 | 65 | 128 | 906 | 90 | 811 | 3115 | 173 | 551 | 870 | 879 | 299 |

| 2008 | 2670 | 1661 | 103 | 117 | 858 | 105 | 897 | 3183 | 211 | 693 | 990 | 895 | 308 |

| 2007 | 2442 | 1486 | 104 | 114 | 793 | 108 | 816 | 2937 | 204 | 562 | 873 | 831 | 310 |

| 2006 | 2159 | 1426 | 65 | 87 | 673 | 79 | 765 | 2746 | 160 | 518 | 887 | 682 | 296 |

| 2005 | 1848 | 1198 | 72 | 79 | 608 | 66 | 624 | 2456 | 119 | 378 | 684 | 591 | 198 |

| 2004 | 1773 | 1207 | 82 | 89 | 696 | 78 | 616 | 2426 | 159 | 382 | 737 | 631 | 207 |

| 2003 | 1740 | 1172 | 87 | 64 | 684 | 60 | 553 | 2233 | 120 | 396 | 696 | 632 | 175 |

| 2002 | 1440 | 1028 | 82 | 55 | 571 | 63 | 488 | 2075 | 108 | 335 | 684 | 511 | 156 |

| 2001 | 1593 | 1123 | 63 | 55 | 505 | 62 | 525 | 2033 | 102 | 390 | 696 | 526 | 158 |

| 2000 | 1315 | 981 | 60 | 54 | 597 | 49 | 442 | 1848 | 96 | 312 | 586 | 415 | 129 |

| 1999 | 1131 | 889 | 61 | 40 | 545 | 39 | 380 | 1619 | 106 | 269 | 514 | 368 | 125 |

| 1998 | 1105 | 897 | 51 | 44 | 545 | 56 | 415 | 1669 | 82 | 280 | 505 | 364 | 113 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kaklauskas, A.; Zavadskas, E.K.; Lepkova, N.; Raslanas, S.; Dauksys, K.; Vetloviene, I.; Ubarte, I. Sustainable Construction Investment, Real Estate Development, and COVID-19: A Review of Literature in the Field. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7420. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137420

Kaklauskas A, Zavadskas EK, Lepkova N, Raslanas S, Dauksys K, Vetloviene I, Ubarte I. Sustainable Construction Investment, Real Estate Development, and COVID-19: A Review of Literature in the Field. Sustainability. 2021; 13(13):7420. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137420

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaklauskas, Arturas, Edmundas Kazimieras Zavadskas, Natalija Lepkova, Saulius Raslanas, Kestutis Dauksys, Ingrida Vetloviene, and Ieva Ubarte. 2021. "Sustainable Construction Investment, Real Estate Development, and COVID-19: A Review of Literature in the Field" Sustainability 13, no. 13: 7420. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137420