Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic, which began in February 2020, has radically changed the processes related to higher education. The main purpose of our study is to help scholar communities distinguish between educational approaches that seek to sustain the “unsustainable” and to identify the problems of lecturer–student interaction in the midst of the mass transition to distance learning and to find ways to solve them. The results of our research show that the transition to distance education during the pandemic took place; however, it highlighted a whole complex of problems connected with deterioration of emotional state and reduction of incentives to study. That might challenge the existing status quo, a revision of the principles of “Humboldt universities” and the birth of new forms of education. The study consists of three parts that allow analyzing the lecturer–student relations, as well as the management of the learning process. The first part analyzes the characteristics and attitudes towards distance education in different countries. The second part presents the results of students’ emotional state in two countries with different population restriction regimes. The third part is devoted to the study of students’ time planning in the distance-learning environment. We used the following methods to achieve the goals of the study: a questionnaire survey of students and lecturers, HADS (The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale), and self-timing method. The thesis about the “gameover” in universities education management is open for discussion by the scientific community.

1. Introduction

The practice of organizing higher education, established by the beginning of 2020, both in Russia and in other countries of the world, assumed that most of the training takes place in the university classrooms, where two parts of the process directly interact: teachers and students. Face-to-face communication, contributing to the free development of education and science, has become the basis of what is understood in European countries as the “Humboldt University” and largely shaped the “Bologna education system”. By the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the share of online education in Russia was just over one percent, and around the world about three percent. In some countries, the share could reach 20–30% [1], but in any case, face-to-face education was dominant by the beginning of the third decade of the 19th century.

It should also be noted that, due to the introduction of mandatory in Russia and, in its own way, progressive Federal State Educational Standards (FSES, Approved by the Ministry of Education and Science of Russia and mandatory for most universities in the country), the increase in the share of self-study in the curriculum did not imply a change in the basic principles of work of classical universities in relation to the forms of education, since a significant or even defining part of knowledge was transferred by the teacher to the students during face-to-face communication.

A 2020 study by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development notes that “the COVID-19 crisis struck at a point when most of the education systems covered by the OECD’s 2018 round of the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) were not ready for the world of digital learning opportunities” [2] (p. 16). In this, we see one of the main problems of the massive transition to distance education immediately after the announcement by WHO (World Health Organization) of the pandemic regime.

At the same time, another OECD report suggested that the heads of educational organizations and national systems, responding quickly to the situation, had to develop plans for continuing education using alternative teaching methods during the period of the necessary social isolation [3,4,5,6].

The International Association of Universities (UNESCO) indicates that in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting rapid transition of universities to distance education, the organization of classes was most often an online imitation [7] (p. 24) of classroom activities. This presupposed the preservation of all the characteristic features of the system, such as the schedule that determined the time and duration of classes, now in virtual classrooms.

In the same study, respondents note that distance teaching and learning requires a different pedagogy and that it is difficult for teachers to make this sudden and unprepared transition from face-to-face to distance learning. The level of readiness to solve this problem among universities and teachers themselves turned out to be quite different [7] (p. 25). The authors of the study, however, note that this is better than nothing at all. At the same time, the load on the teacher increases, since “technology does not just change methods of teaching and learning, it can also elevate the role of teachers” [2] (p. 16).

In a pandemic around the world, university heads had to re-invent how to manage their campuses. [7] In the Russian Federation, the difficulties of transition were aggravated by the bureaucratization of education, which made it necessary to preserve the well-established processes of planning, organization, coordination, and control characteristic of the “previous” face-to-face form of education. It is difficult to blame solely the administration of universities for trying to preserve such a status quo, since the Russian tradition of law-making and the practice of its application is, in principle, focused on “paper” document flow and a pseudo-bureaucratic approach to managing organizations.

All this determined the relevance of the topic of our research, the main goal of which was to determine the problems of interaction between a teacher and a student during the massive transition to distance education and to find ways to solve them.

In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic, which began in February 2020, made changes in the daily life of people around the world and changed the rhythm of current processes [8,9]. The population of the countries could not foresee and did not expect the closure of borders, restrictions on leaving home, and transfer of work and education to online formats [10,11,12,13,14]. The fact that these restrictions would affect the psyche of people did not raise doubts already at the beginning of the pandemic, but no one could give any forecasts of what changes they would be and how deeply they would affect people. The present study is also aimed at determining the levels of students’ personal anxiety and depression. We aimed to study the impact of the global crisis caused by COVID-19 on the mental health of students who were forced to move their education online and determine how this affected the learning process.

Therefore, the second goal of the study was to compare anxiety and depression among students from the two countries during the second wave of the 2020 pandemic. The choice of the countries—Russia and Turkey—was due to the different state attitude to the epidemiological situation in the fall of 2020. In Turkey, a rather strict regime of self-isolation was introduced, citizens were not allowed to leave their homes freely, masks had to be worn on the streets, all training was conducted online, and sports clubs were closed. In Russia, during this period, it was possible to walk, move on the street without masks, go in for sports, and training was practiced in two forms: online and offline.

In different countries, the authorities regulated life in cities in different ways: somewhere a state of emergency was introduced (for example, in several US states), somewhere a self-isolation regime (for example, Russia), somewhere a full-fledged quarantine (for example, Germany), in Sweden, a lightweight regimen was implemented in the fight against coronavirus. In this regard, it was logical to ask the question of how the same or different will be the changes in the psycho-emotional state of people living in countries with different restrictive measures. Additionally, again, how will this affect the propensity of students to perceive new knowledge in the learning process?

Therefore, the third goal of the study was to compare anxiety and depression in Turkish and Russian students throughout the entire period of the pandemic when restrictive measures were changed. The study was carried out in two stages: May 2020 (restrictive measures have been introduced and have been in effect for about 2 months) and December 2020 (restrictive measures have been introduced and operate differently in different countries for 9 months).

The choice of countries, in this case, was due to the different state attitude to the epidemiological situation. If in Russia and Turkey in May the self-isolation regime was almost identical (people could leave their homes with passes, without moving far from their place of residence, it was only necessary to maintain a social distance, it was necessary to use masks on the street and in public spaces), then in the fall the situation in countries changed.

In Turkey, new restrictive rules entered into force in November 2020: a curfew was introduced. Therefore, according to the document signed by the President of Turkey, a ban on going out on weekend evenings was introduced: from 20:00 every Saturday to 10:00 every Sunday and from 20:00 Sunday to 05:00 Monday. Restaurants and catering facilities were open until 20.00, selling food only to take away; shopping centers were also open until 20.00. Residents of Turkey aged 65 and over could only go for a walk on weekdays from 10:00 to 13:00, and the age group under 20 (those born from 1 January 2001 and after) could go for a walk from 13:00 to 16:00. In Russia, in particular in Moscow, since the beginning of June 2020, there have been no bans on going out for all the categories of citizens, restaurants and catering places are open in the usual format until 23:00; shopping centers are also open until 23:00.

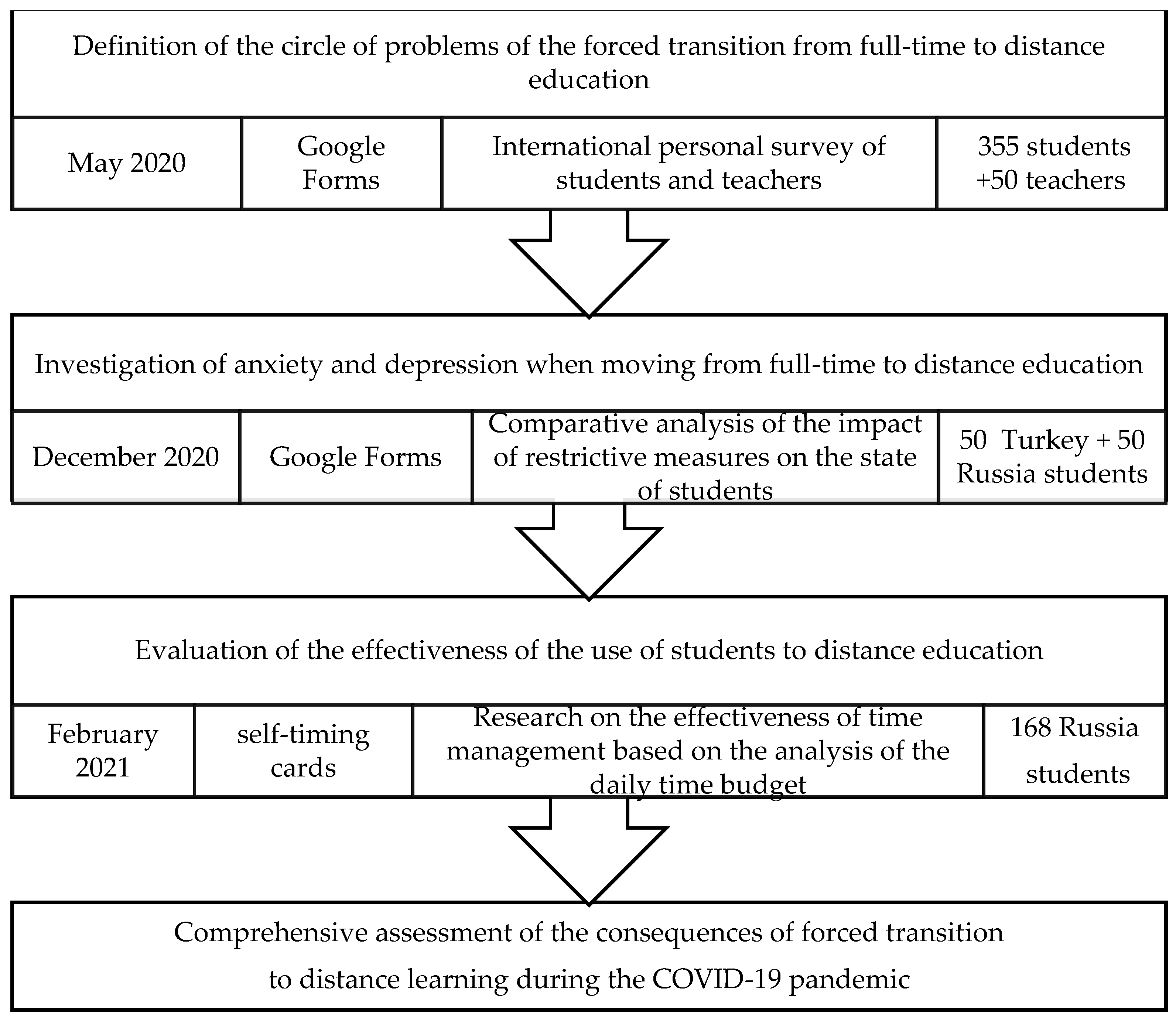

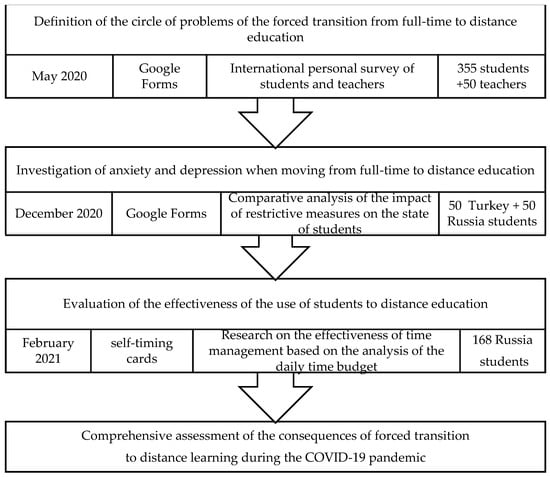

Thus, our article consists of three parts, each of which can be considered as an independent study, but all together they make it possible to analyze the situation (first of all, the relationship between teachers and students and the emotional state of students) in the system of organizing higher education after the massive transition of universities for distance education during the COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Research algorithm.

In the first part, based on a survey of students and teachers in different countries, the peculiarities and attitudes towards distance education are analyzed.

The second part presents the results of the emotional state of students in two countries with different regimes of restrictions for the population.

The third part is devoted to the study of time planning by students in the context of distance learning.

To substantiate the author’s hypothesis about the problems and perspectives of organizing the learning process, we will conduct a literature review of publications devoted to organizing the learning process in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Situation: Literary Review

2.1. Problems of Distance Education

Having a review of publications, the authors want to immediately note that the object of study is not distance education in a broad sense, but the problems of the forced transition from full-time to digital form education. Distance education even before the pandemic was in a separate appearance, requiring a thorough study of its diverse forms. However, within the framework of this article, the authors cannot pay due attention to the coverage of the development of distance learning. The authors focused on the problems of forced refusal from full-time education and unplanned transformation to distance learning technologies.

Based on the analysis of publications in 2020 devoted to identifying the changes that have occurred in the process of transition of national educational systems to distance education due to the pandemic, two groups of problems were identified—problems arising on the part of teachers and students, which resulted in a communication problem—the knowledge transfer system was imbalanced for some time, and the organization of the parties’ time changed significantly.

2.1.1. Challenges for Teachers

Marinoni et al. [7] write that in many universities around the world, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, classroom teaching was replaced by distance learning. The transition from face-to-face to distance education itself was not without problems, among which the main ones were access to technical infrastructure, pedagogical techniques, and methods of distance education.

Regarding the characteristics of face-to-face teaching, Bao [15] notes that in the classroom, body language, facial expressions, and voice of the teacher are important teaching tools. However, once the course is converted to distance learning, the ability to use body language and facial expressions diminish as these tools are difficult to translate across user screens. Only voice remains as a full-fledged tool. Therefore, Bao believes, when teaching online, teachers should be more careful about the speed of their speech so that students can better assimilate key knowledge.

The same paper, referring to a comparison with traditional lectures in classrooms, notes that teachers have less control over online learning and students are more likely to “skip classes”. Thus, the online learning process and its effectiveness largely depend on the activity of students and not only during classes. For this purpose, teachers should use a variety of methods for homework and student self-study requirements to enhance active student learning outside the classroom [15].

Noting the difficulties faced by students, Schleicher [2] writes that while university administrations during this period made concerted efforts to maintain the continuity of education, teachers had to adapt to new pedagogical concepts and teaching methods that they may not have been trained and prepared for. Students also had to rely on their own resources to continue their studies remotely via the Internet or other means of communication.

2.1.2. Students’ Problems

Jena [16] draws attention to the fact that many students have limited or no access to the Internet and are unable to afford a computer, laptop, or smartphone at home. Thus, distance learning can create a digital gap between students. For example, isolation hit poor students in the country he describes (India) extremely hard, as according to various reports, most of the students did not have the technical ability to study online. Thus, it concludes that the online learning method during the COVID-19 pandemic could widen the gap between rich and poor, urban, and rural learners.

Daniel [17] writes that the COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted the educational life of students in different ways, depending on which course of study they were in and what level of academic progress they achieved in their programs. Many of the students, when moving to the next level of education or entering the labor market, begin to worry that they have received less knowledge. It can be assumed that this will have long-term implications in self-esteem compared to those who studied “normally”. Various studies also predict that the changes in the format of education that have occurred can negatively affect the economic development of countries in general and, as a result, negatively affect the growth of the world gross domestic product (GDP), but this aspect is beyond the scope of our study.

In addition to technical problems, Bao notes [15], according to the analysis of student responses in social media, students often face such problems as lack of self-discipline, appropriate teaching materials, or appropriate learning environment when they are isolated at home.

To better understand why this has happened and how dramatic changes in the organization of education have affected the entire system, we will consider some psychological aspects in relation to the main object of education—students.

2.2. Psychological Problems of the Lack of Face-to-Face Communication

The global health crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and characterized by high levels of uncertainty, risks, and threats to life, has had a profound effect on people’s anxiety levels. The high prevalence of the disease, the lack of guaranteed treatment options and the uncertainty of the entire pandemic process posed a particular risk to the mental health of society as a whole. The reduction in social contacts and the practice of quarantine increased anxiety and also contributed to the emergence of depression in people.

Anxiety is defined by Z. Freud as “something felt, an emotional state that included feelings of apprehension, tension, nervousness, and worry accompanied by physiological arousal” (cited by [18]). According to the American Psychiatric Association [19] (APA, 2013), anxiety is the response of a person’s body to a perceived threat, characterized by anxious thoughts, tension, high blood pressure, respiratory rate, pulse, sweating, difficulty in swallowing, dizziness, or chest pain caused by a person’s beliefs, emotions, and thoughts.

Anxiety includes cognitive, emotional, and behavioral processes aimed at preventing or reducing the impact of a potential threat. When these processes are implemented at a balanced level, they can function adaptively. However, they can also be maladaptive when over-embodied [20].

Basic models of anxiety-related psychopathology indicate that anxiety and fear have three main components. These are physiological (activation of the autonomic nervous system), cognitive (interpretation of external and physiological stimuli), and behavioral (selective response to stimuli) responses. Fear is seen as a defensive reaction to a threatening situation with strong physiological reactions and behavior aimed at fighting or fleeing from the source. Anxiety is physiologically similar to fear because it enhances autonomic excitement. On the other hand, anxiety arises in response not to an existing identifiable threat, but to a potential threat. An important cognitive distinction of anxiety is the feeling of uncontrollability, which takes into account the possibility of future threats, hazards, or other potential negative events [21] (Carleton, 2012). Fear and anxiety can be categorized in terms of how confident they are about the likelihood, timing, or quality of a future threat [20].

Negative life events with potential threats such as interpersonal conflict, illness, financial hardship, loss, and mourning often cause anxiety disorders [22,23]. In stressful situations, such as life crises and mass trauma, anxiety patterns are observed not only in those who are directly affected, but also indirectly, as well as, for example, through the effects of images broadcast by the media [24]. Experts predicted that the perception of threat and uncertainty in the COVID-19 pandemic would cause anxiety problems not only for patients, their relatives, medical and social workers in the field of public health but also for the entire population subject to this perception.

Based on the interaction between the person and the environment, the cognitive assessment process determines why and how stressful a situation is. When people are faced with a crisis in life, they first assess whether potential stressors are important to the well-being of themselves and the people they love. When an event is perceived as threatening, a secondary assessment process is triggered, during which stress responses arise. In this case, people evaluate psychological (self-esteem, optimism, self-control, etc.), personal (income, education, professional status, etc.), and social (family stability, social support, etc.) resources that increase resistance and ability to cope with difficulties [25].

We will consider that anxiety is an unpleasant emotional state that manifests itself in a feeling of uncertainty, trouble, tension, and fear experienced by living beings. Depression is a common and serious but treatable medical condition that negatively affects the way a person feels, thinks, and behaves. Depression leads to a constant state of sadness and an inability to enjoy situations that are pleasurable. Depression can manifest itself in a variety of emotional and physical symptoms. Both anxiety and depression greatly reduce the quality of life, worsen the mental and physical condition of a person.

Threat perception, uncertainty, and anxiety over the COVID-19 pandemic can be seen as a crisis that has affected a significant proportion of the world’s population [18]. A crisis is defined as a period of the psychological imbalance that occurs as a result of a threat or event that indicates a serious problem that cannot be addressed with known coping strategies. A crisis can take the form of one or a series of successive stressful events that quickly produce a cumulative effect. In the acute phase, people experiencing a crisis may display such reactions as denial, confusion, anger, fear, anxiety, detachment, or depression [18].

For the purposes of this study, we will assume that anxiety is the result of internal conflicts, this is behavior and a defensive reaction to the desire of living beings to adapt to the external environment. Depression is a condition that is caused by a combination of various factors; it includes the symptoms of various disorders, refers to a mental disorder that has a negative effect on the body as a whole. Both anxiety and depression greatly reduce the quality of life; they worsen the mental and physical state of a person.

These and other aspects formed the need to study the factors by which there was an imbalance in the interaction of teachers and students and what it could lead to in terms of learning, the formation of competencies and personality.

3. Materials and Methods

To achieve the main goal in the first part of the study, we conducted a survey of teachers (see Appendix A) and students (see Appendix B) from countries close in terms of the organization of the education system: Russia, Kazakhstan, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic. We used Google Forms for the survey. The form of the questionnaire is posted in annex A and B to the article.

In total, 355 people took part in the study among students: the Russian respondents—80% (285 people); those from Kazakhstan—13% (53 people); 7% in total were students from other countries. According to the programs, students were distributed as follows:

- 1st year of study—26% (95 people);

- 2nd year of study—43% (152 people);

- 3rd year of study—18% (63 people);

- 4th year of study—9% (31 people);

- Master’s degree programs—3.7% (13 people).

The largest number of students, 62.8% or 223 people, are trained in “economics and management”. Students of the social and humanitarian direction accounted for 18.9% or 67 people. The rest of the directions are represented insignificantly.

A total of 50 teachers took part in the survey: 12 men and 38 women. They were distributed by age as follows: from 25 to 30 years old—10%, from 35 to 55 years old—60%, from 55—to 65 years old—22%, over 65 years old—8%. The majority of teachers (96%) read lectures and 4% teach only seminars. A total of 86% of teachers are associated with the direction of “economics and management”.

In most of the universities in which the survey was conducted, the educational process is carried out synchronously in accordance with the approved schedule of learning sessions and thus fully simulates the classes on the campus. For example, in Russia, the Webinar.ru service is used to conduct lectures and consultations for exams; for practical exercises, report protection, and laboratory exercises—Zoom.com is used; for examinations—Zoom.com and systems based on Moodle are used. The examination is accompanied by a proctoring procedure, i.e., identification of the identity of the student who presents an identity document, student card, or grade book. The student, while passing the intermediate certification, must be in audio and video communication with the teacher. Issuance of assignments and acceptance of students’ written work is carried out on the Moodle platform. In additional cases, the use of the MS Teams platform is allowed. In other countries, teachers noted a similar system of conducting classes, which is based on a synchronous mode—pairs of two academic hours.

In the second part of the study on the topic of anxiety and depression, another 50 students from Russia and 50 students from Turkey took part, the age of the subjects ranged from 18 to 21 years. The majority of respondents from Turkey (45 people) were subject to the restriction on free access to open street spaces.

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [26], developed for the primary detection of depression and anxiety, was chosen as a methodology for the study of anxiety. This scale helps to understand the emotional state of a person at a certain period of time. The choice of the methodology was due to the fact that it was translated into the national languages of Russia and Turkey and met all the psychometric requirements.

In the third part of the study, as the part of the study of the discipline “Time Management” during the period of distance education, the timing of the use of time by the first year Bachelor’s programs students in the direction of “Advertising and Public Relations” of the Plekhanov Russian University of Economics was carried out. The timing was carried out by the self-timing method. First, the students studied the methodology, then they measured their time spent and checked the results with the teacher. Thus, significant coverage of the participants in the experiment and high reliability of the results obtained were ensured. The experiment was carried out in 6 groups with a total of 168 people. Timing measurements covered three weekdays of the academic week, during which students had an academic load in a distance form. Thus, each student measured 72 h spent on their own time, and the total balance of the studied hours was more than 12,000 h on average.

4. Results of the Study of the Attitude of Teachers and Students to Distance Education

Surveys of the two parties involved in the educational process—teachers and students—for the main study were conducted in December 2020.

4.1. Students Survey

After the introduction of distance education, 55% of students answered that the preparation for classes remained the same, 45% that they were preparing more. Answering the question whether they started attending classes more, 68% of students answered that the introduction of distance education did not affect their attendance in any way; 20% began to attend more often; this circumstance did not affect 11%.

Half of the students surveyed believe that the quality of knowledge obtained through distance education has remained at the same level. The same percentage of respondents (46.5%) believes that the quality of knowledge has decreased. Interestingly, 6.8% believe that the quality of knowledge has improved. These are exactly those students who began to attend classes and learned new scientific information (“an opportunity to attend seminars has appeared”) after the need to go to an educational institution has disappeared.

Difficulties in their own concentration in classes are considered by most students as the main reason for the decrease in quality. It is noted that there are many distractors at home, and there is no external control over assignments. During face-to-face classes, one can immediately ask a question if something is not clear. With distance learning, especially on the Webinar platform, where communication occurs only via text messages during lectures, this is not possible. Often the teacher already moves on to the next point of the lecture, leaving the question unanswered. We see that for the overwhelming majority of students (89.3%) it is important to express their position, to actively participate in the discussion. That is why the Zoom system, in which all the participants in the educational process can participate in the discussion, received the largest percentage of votes (71%).

The lack of direct contact with the teacher also worsens the perception of the material (“it is very difficult to perceive the material without live communication”). For the majority of students (77%), it is important that the lecture is accompanied by a presentation. Moreover, half of the respondents want to see the teacher himself, the rest only need to hear him. The majority of students noted the need for feedback.

Of course, technical problems are a separate point of the negative perception of distance education. The Internet, without which it is impossible to obtain high-quality educational information, does not work well in all the regions of the country. Students note that it takes a very long time to configure the appropriate platform. Moreover, there is confusion about what subject, when, on what platform (Zoom, Webinar, Moodle, email). In addition, links are often broken. Additionally, students pointed to a deterioration in their health due to the constant sitting in front of the monitor (“in the evening the head starts to ache”, “watery eyes”, “back hurts”).

Additionally, students mention the unwillingness of some teachers to work at a distance (“not all responsibly approach their courses”). Learning difficulties also arise because it is difficult for teachers to assess the new energy consumption of students for learning in new conditions. There was a certain idea that there was more time for study due to the reduction in time for commuting, and in this regard the number of homework assignments increased, although they were not adapted to the new educational format (“the main thing is to send it on time”). We can say that some teachers do not know how to use the provided technical capabilities, but “just overwhelm with assignments”.

The authors consider it important to note that in the real practice of teaching teachers and students, there were simultaneously multiple remote forms. All universities were forced to recommend their teachers at the same time as internal and external resources due to imperfection. Distance education developed as a separate direction in terms of the use of various digital forms. However, with a total transition to distance learning that covers all the national education, no resource has not been ready for mass use in the learning process.

It should be remembered that communication with classmates, the opportunity to discuss with them both scientific and everyday issues, plays an important role in the educational process. Higher education allows one to establish the necessary contacts, socialize, which in the future will have a positive effect on employment. More than 70% of students note a lack of live communication in the classroom.

4.2. Teachers Survey

After the introduction of distance education, 100% of the interviewed teachers began to spend more time preparing for classes, both for lectures and seminars. A total of 41% noted that they began to prepare presentations for better assimilation and systematization of the material by students. A total of 83% said they reviewed the course to improve its design. All interviewed teachers note the importance of interactivity in classes for discussing scientific and practical issues. Most teachers (80%) emphasized that they would like to see students on a computer screen. Thus, the most preferred system for them is Zoom (66%), where there is an opportunity to quickly establish contact, directly communicate, exchange opinions, and conduct discussions.

The majority of teachers (75%) believe that the level of knowledge gained by students in distance learning has become worse than in face-to-face education. The greatest negative is associated with the lack of interaction with students (70%), as well as the inability to check whether assignments are being completed independently (52%). The inability to organize a discussion in groups (30%) can be attributed to purely technical difficulties.

Additionally, 100% of teachers have become more attentive to their words at a lecture. A total of 62% of teachers fear that their classes might be posted online without their consent. At the same time, 58% of them are indifferent to the idea that colleagues and management can attend classes. It causes discomfort in 22% and is inspiring for 20% of the respondents.

For effective work in a distance mode, teachers believe that it is necessary to reduce the volume of their own academic load since such classes require more preparation. Additionally, there should be a different, higher payment for distance teaching.

In addition, we see that students’ motivation in the distance mode is not very high, and the teacher will have to face low motivation. This means that he will also have the function of motivating students.

Let us consider the psychological aspects of student behavior—levels of anxiety and depression—in two countries with different regimes of restrictions during the second wave (fall 2020) of the COVID-19 pandemic.

4.3. Students’ Anxiety and Depression

The authors used the scale (HADS), which is a recognized method of screening detection of anxiety and depression. The treatment of respondents’ answers allows you to identify three levels of the emotional state of the student: the norm, subclinical, and clinical alarms/depression. Each estimate is characterized by a deterioration of the state of discomfort in disturbing and depressed as students’ disease. We do not give the scale as it is a commonly pre-form of the survey of respondents.

Based on the results of determining the emotional state of students during the coronavirus period, it was revealed that the clinical expression of depression was manifested in 7% of Russian students and 33% of the Turkish students. The subclinical expression of depression was observed in 13% of the Russian students and 20% of the Turkish students. The norm was detected in 80% of the Russian students and 47% of the Turkish students.

The clinical expression of anxiety in the Russian students is 27%, and in the Turkish students—73%. The subclinical expression of anxiety is detected in 20% of both Russian and Turkish students. The normal expression of anxiety is observed in 53% of the Russian students and 7% of the Turkish students.

According to the data obtained, we can say that the level of anxiety and depression differs in Russia and Turkey. For Turkish students, the self-isolation process has exacerbated the problems of anxiety and depression to a much greater extent. This can be attributed to the severity of measures to counter the spread of the coronavirus infection.

Students have to spend most of their time in a confined space, have limited opportunities for walking, including the lack of free access to fresh air, which increases the psychophysiological symptoms of anxiety and depression. The prolonged stay in the same environment, communication with only the same people (mainly with parents) also increases emotional stress. Conflicts, quarrels of people who have been in a confined space for a long time, reduce adaptive capabilities and increase the level of stress.

The opening hours of restaurants and cafes in Turkey have decreased since November, they work from 10 a.m. to 8 p.m., selling food only to take away. While in Russia in November restaurants and cafes were open to visitors from 8 a.m. to 11 p.m., most of the halls were open, in which guests could spend time eating. The Russian students have access to sports sections, can meet with their friends, and attend educational institutions.

Despite continuing restrictions, the overall situation in Russia is more relaxed than in Turkey, which contributes to the mild manifestation of clinical and subclinical anxiety and depression.

Let us compare the dynamics of the situation: initially, in both countries, there are equally strict restrictions, which then turn into a decrease in requirements in one country and the preservation of the regime in the other.

4.4. Dynamics of Anxiety and Depression

4.4.1. Anxiety

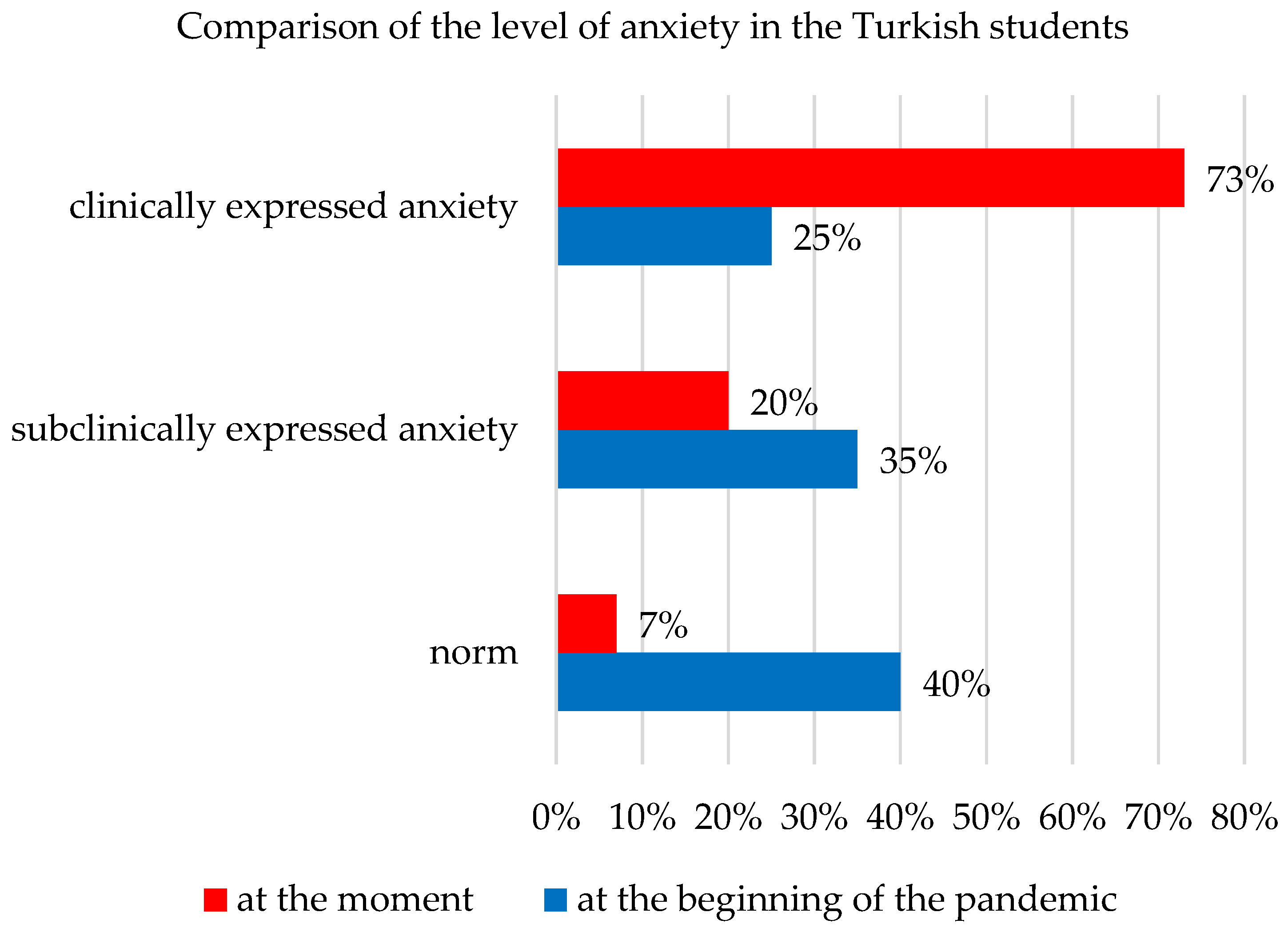

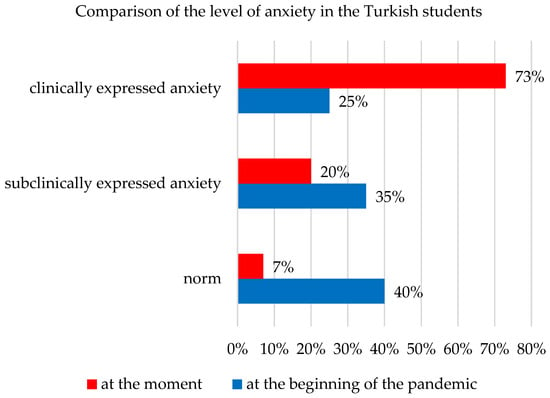

We see that at the beginning of the pandemic, the level of the normal expression of anxiety of the Turkish students was 40% and in December only 7%. The level of the subclinical anxiety decreased from 35% to 20%, and the level of the clinically expressed anxiety rose from 25% to 73% (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Comparison of the level of anxiety in the Turkish students.

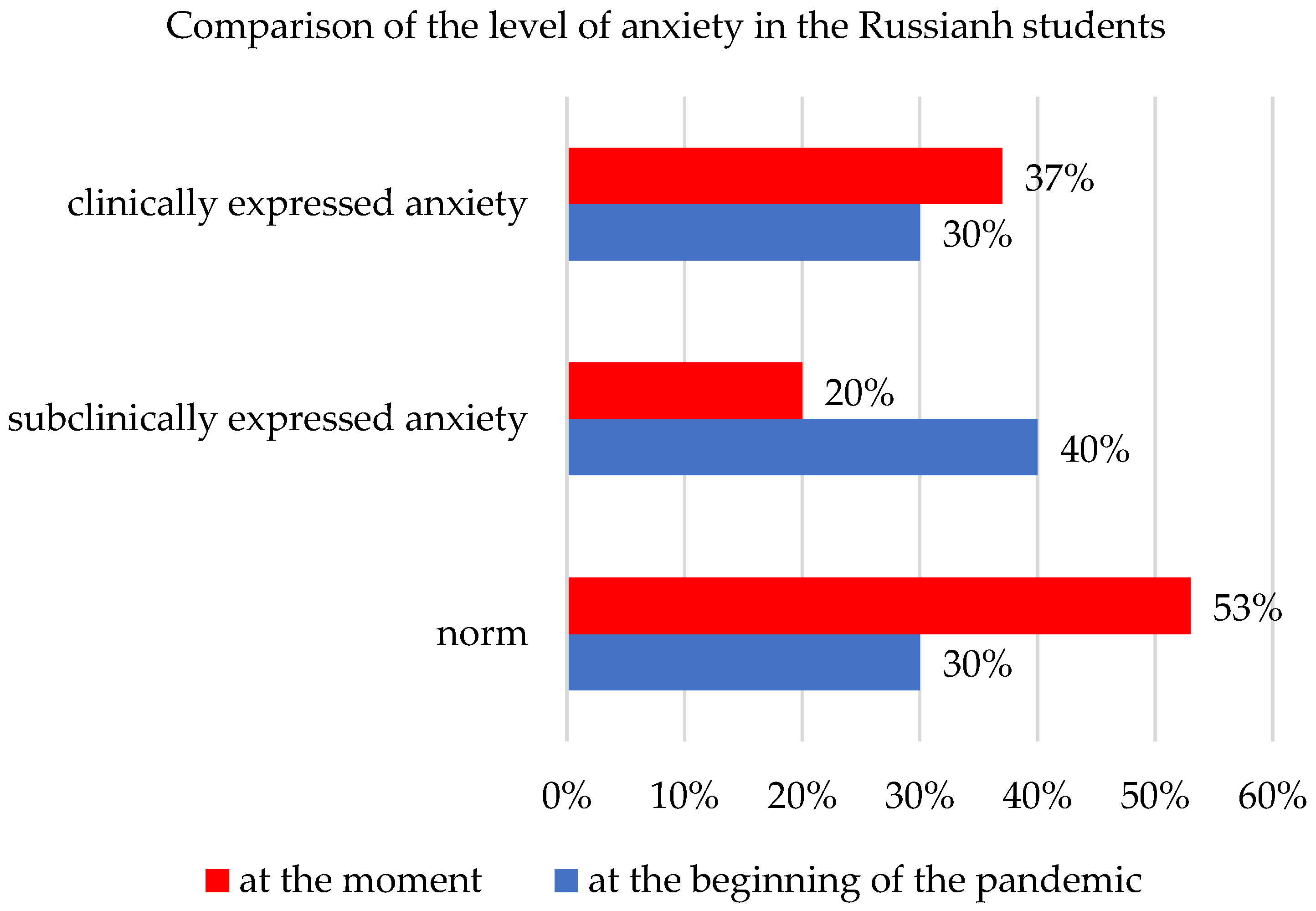

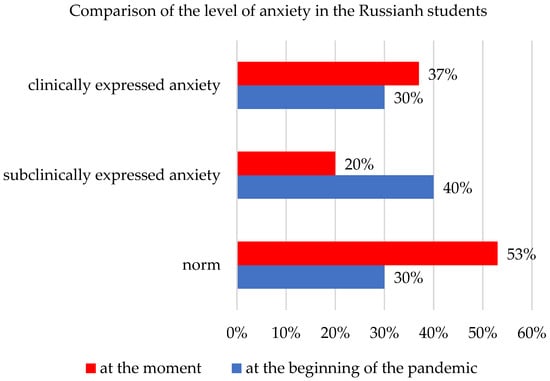

In the Russian students, in comparison with the beginning of the pandemic, the norm in the expression of anxiety obviously increased from 30% to 53%, at the same time, the subclinically and clinically expressed anxiety decreased (from 40% to 20% and from 30 to 27%) (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Comparison of the level of anxiety in the Russian students.

4.4.2. Depression

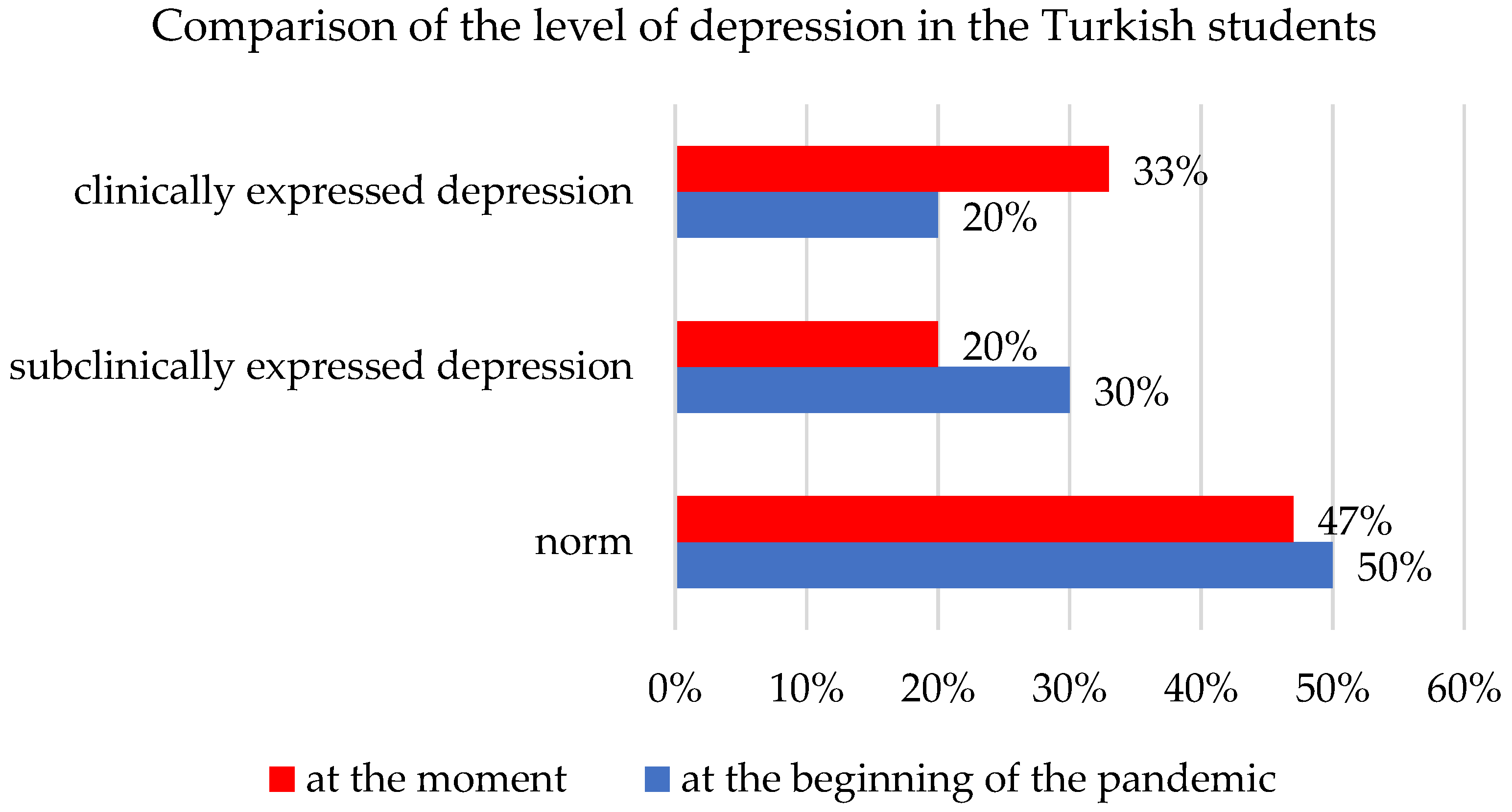

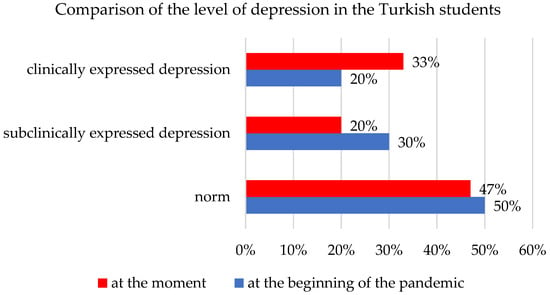

In the Turkish students, in comparison with the beginning of the pandemic, the norm decreased slightly (from 50% to 47%), the subclinical depression decreased from 30% to 23%, and the clinically expressed depression rose from 20% to 33% (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Comparison of the level of depression in the Turkish students.

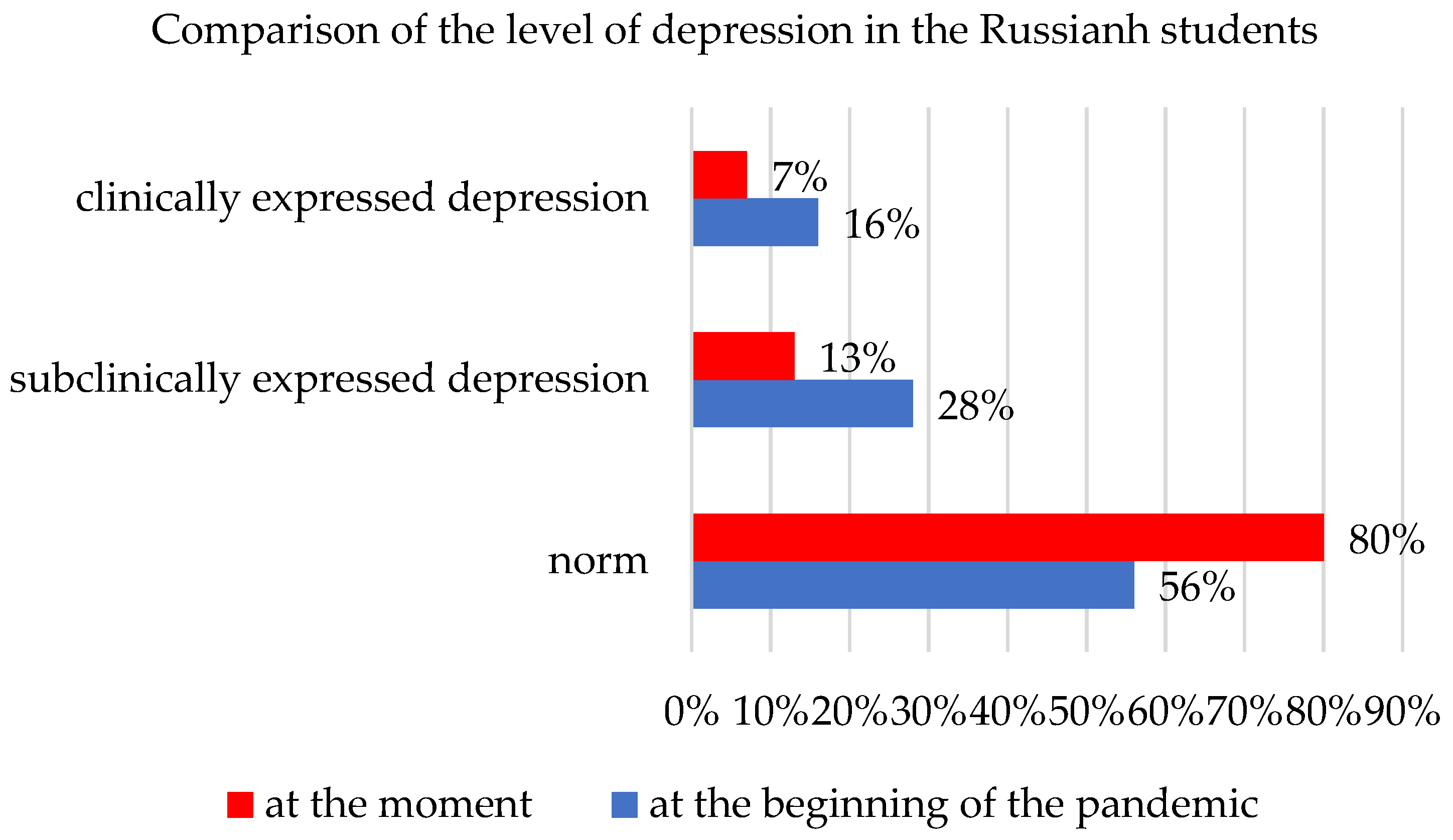

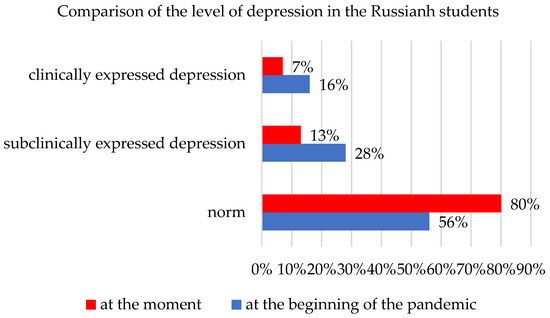

Compared to the beginning of the pandemic, the norm of depression in the Russian students increased from 56% to 80%, while the subclinically and clinically expressed depression decreased by almost half (from 28% to 13% and from 16% to 7%) (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Comparison of the level of depression in the Russian students.

Based on the above survey results, it can be noted that the psycho-emotional state (the level of depression and anxiety) in the Russian students improved by December, while in the Turkish students, the response norms in both scales decreased, and the clinically expressed anxiety and depression increased, and we can say, that their psycho-emotional state worsened.

Analyzing the data presented, we can assume that the Russian students managed to better adapt to the situation of the pandemic, reducing the feeling of helplessness, decreasing anxiety from a situation of uncertainty. This is largely due to the greater movement freedom, including in the fresh air, the resumption of meetings with friends, as well as direct visits to the educational institution. Despite the remaining restrictions (wearing masks in public places, maintaining social distance), there is a certain return to the usual way of life.

We see that in May the indicators of the Russian and Turkish students were approximately similar in terms of the norm, subclinical and clinical anxiety, and depression, but in December these indicators differed significantly. In May, the pandemic situation was new for everyone; people did not know how long the disease and the isolation associated with it would last. In addition, there was no exact understanding of the whole picture taking place. The measures introduced by Turkey and Russia were initially identical, and people’s experiences were also similar. However, as the situation developed and new measures were introduced or old restrictions were lifted, it affected the emotional state of people in different ways. Additionally, the indicators started to differ from each other. In addition, the difference in mentality also plays its role. The Russian students note that they are tired of being afraid and they want to quickly return to the old world, their usual regime. In Turkey, students show greater discipline and are ready to wait for the disease to subside without breaking the rules.

4.5. Self Timing of the Use of Time by Students Studying in the Distance Mode

Each student measurement results were summarized as a three-day average of the time-use balance. When processing the average balances of time, three categories of a typical structure of time spending were identified; they are presented in Table 1 below.

Table 1.

Structure of students’ time spent.

The division into groups was carried out on the basis of the use of the time released on distance learning. Part of the students used the time to invest in future competencies and work. This category is working students. If students spent the time resource inefficiently called “resting”. The group in which the balance of the time has not changed with the transition to distance learning is a “Middle subgroup”. During the self-timing process, students recorded the actual use of time, which was then attributed to one of the ten-time spending items. The time spent on sleep turned out to be the most understandable category, but it was this item that turned out to be the main resource, marking the typology of student behavior during quarantine, which we would write about below.

Time spent on hygiene, food intake and other individual physiological needs were included in the category of personal needs. The average share of this time spending item remained stable, as no one could neglect it.

The time spending item “family” included the time spent on fulfilling social obligations in the family: both doing chores and various assignments and communicating with family members. We will see the difference in time spending for these items depending on the characteristics of the subgroup.

Entertainment and hobbies are the most varied in terms of content since both sports and the time of watching the series were attributed to it. The unifying principle of spending time in this item is the individual choice of the student to receive benefit or pleasure from spending this time.

Time to communicate with friends was allocated in a separate item since for students this is an activity that marks their belonging to a social group. By the differences in the time devoted to communicating with friends, it will be possible to trace the change in social roles.

Studying at the university and the time spent to get there are also easily estimated time spending items. The time of the study was traditionally considered as the time of classes and the time of preparation for them. Hypothetically, this time could remain unchanged during the transition to distance learning since the educational process was carried out in full.

Time spent on commuting requires further explanation. Usually, students studying in Moscow inevitably spend much time on commuting. The transition to distance learning freed up a significant resource by eliminating classroom attendance and significantly reducing the need for other movements. Saving commuting time was to become the main resource for distance working in the metropolis.

In the process of processing primary measurements, it became necessary to take into account additional items: work and additional studies. Each of these items is considered by us as an investment in the quality of human capital. The usual practice is a set of students for 4 h of collaboration. However, studies have shown that a significant part of students works by freelancers, and their work hours depend on the projects over which they work. The average time spent on the paid work was 3.5 h.

Additionally, the final item of the time balance—losses—primarily assumed the accumulation of technical losses of time—waiting for an event, searching for a lost thing, fixing a broken thing and other non-productive costs. However, after the first day of measurement, practically all the students found that some of their time was wasted on social media or simply in a state of physical stagnation. Figuratively, the students called these losses “to be slow on” and it was precisely this kind of time spending that filled the item of losses and became a marker for different groups.

The main unexpected conclusion for the students was that they literally slept through the first year of distance education. Average sleep time increased in 82% of students. Earlier, before the transition to the distance format, students on average spent 7–7.5 h sleeping on weekdays and simply could not afford more without compromising on obligations. The transition to distance learning increased the sleep time in the main group by 1.0–1.5 h, and a separate group called “resting students” stood out in which the average sleep time increased to 9 h. At the same time, 10 h were not uncommon in this group, and the maximum amount of time (about 14 h) for sleep was timed in 2 people.

First-year students perceived sleep as an opportunity to recover from the laborious graduation period of secondary school and took the opportunity to sleep, so to speak, “for the future”, so almost all the students took advantage of distance learning to increase their sleep period. However, in general, this did not lead to the accumulation of vital resources and an increase in the productivity of using their own time.

As it turned out, about 23% of students were unable to switch from the model of temporary rest to the new model of the student in the distance mode. We called this subgroup “resting students” because recreational items predominated in the balance of time spent. For this subgroup, the main time spent can be considered unproductive. Time for family and personal needs did not increase. In addition to sleep, it was almost entirely spent on entertainment, communication with friends and sitting on social networks. We can say that every fifth freshman was not ready for independent time management and, as a result, lost the first year of study in terms of developing his own competence and competitiveness as a future specialist.

5. Discussion

5.1. Organisation of the Distance Learning Process

Daniel [7] asks which curriculum should be used by teachers for distance learning during the COVID-19 crisis and notes that the answer will largely depend on national law. Some national jurisdictions have prescriptive (mandatory) curricula, while others give teachers large discretion in the choice of program content. The general advice is to remind one that it is important to be curriculum-oriented, and it is also important to keep students interested in learning by giving them various kinds of assignments. His article notes that there is nothing wrong with using materials prepared by others. It also seems possible for us to organize working groups at departments to develop a new type of assignments, cases more suitable for a distance learning format.

Tosun [27] notes that one of the most important elements influencing the success of distance education is ensuring that teachers and students have positive attitudes and behavior regarding distance education. The recent studies on this topic are presented in the specialized literature [28,29]. For this purpose, classes may be held at universities to discuss the philosophy, structure, functioning and contribution of distance education. University webpages, official social media accounts, internal forums can also be used to provide students with information on current distance learning opportunities and raise awareness. This information can stimulate teachers and students to distance education, as well as build a positive attitude towards learning, which can also help reduce anxiety and depression.

According to Schleicher [2], although universities are trying to enrich and complement their learning environment through digitalization, it cannot replace the relationships between teacher and student that develop in face-to-face education. On the other hand, according to Garrell (1997), regardless of the method used for distance education, encouraging and facilitating the continuity of communication between teachers and students is one of the keys to success in distance education (cited in [27]).

5.2. Changing the Schedule of Face-to-Face Classes

As perhaps the most important adjustment for those accustomed to learning in the classroom in real time, Daniel advises “take advantage of asynchronous learning” ([17], p. 93). For most aspects of learning and teaching, participants do not need to communicate all at the same time. Asynchronous work gives teachers the flexibility to prepare teaching materials and allows students to combine classroom and independent work. That being said, asynchronous learning works best in digital formats. There is no need for teachers to deliver material at the scheduled time: it can be posted on the Internet for access upon request, and students can interact with it using technical means according to their timetable. Professors can periodically check student participation and schedule online appointments for students with special needs or questions. Creating an asynchronous digital classroom gives educators and learners more opportunities to interact.

“Similarly, video lessons are usually more effective—as well as easier to prepare—if they are short (5‒10 min). Organizations offering large-enrolment online courses, such as FutureLearn, have optimized approaches to remote learning that balance accessibility and effectiveness. Anyone asked to teach remotely can log in to a FutureLearn course in their subject area to observe the use of short videos. Teachers might also wish to flag relevant online courses to their students” ([17], p. 94). In the future, the authors suggest additional research related to the possibility of adjusting the schedule and the use of various technical means based on the convenience of participants in the educational process.

5.3. Psychology of the Transition Problem

Tosun [27] note that one of the biggest challenges faced by students in a pandemic is a learning environment that is not adapted to their needs, which also contributes to increased levels of anxiety and depression. During periods of transition to compulsory distance education, when classes are not conducted individually, the number of hours of classes is limited, it is necessary to prepare for the creation of a special learning environment conducive to effective learning. Thus, significant support is provided for the individual teaching of students with different psychological characteristics.

The rapid transition of universities to distance education due to the pandemic had negative psychological consequences for teachers and students, because all the participants in the educational process faced the problem of learning, adapting to intensive work in the distance format, in which they were quickly and unexpectedly involved. In addition, some educators consider it difficult to find a balance between research and teaching roles [30]. All these factors can exert psychological pressure on teachers and, as a result, the outburst of negative emotions on students.

Illness, as well as the death of loved ones from COVID-19 are factors that can affect teachers and students psychologically. Wishing to reduce the level of anxiety and depression, many universities supported teachers, students, and other employees with printed and visual materials, adding links to information about the coronavirus on their official websites, and held seminars on the prevention of emotional disorders.

It is important that the channels of communication between students and teachers-administrators of pedagogical work are open and function without interruption. This support is especially needed during distance education when face-to-face communication takes place only in a limited time using digital media and tools. Phone calls, SMS, email, forums, chat rooms, live lectures, and social media should be actively used to support the educational process. Rules and procedures for the exchange of information to be carried out through these tools should be defined, communicated to all the academic staff and students, and enforced. Ultimately, all the activities should be aimed at improving the educational process and maintaining the psychological health of all the participants in the educational process, regardless of state measures aimed at preventing the spread of the pandemic.

The COVID-19 pandemic has increased the level of anxiety that increases in stressful living conditions. Based on the conducted research, we see that in a country where the situation of prohibition is more pronounced, and new, strict norms of interaction with the environment are introduced, an increased level of anxiety and depression is more expressed.

5.4. Transition Advantages

Jena notes that the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the adoption of digital learning technologies. Educational institutions have switched to a mixed mode of education. This encouraged all the teachers and students to become more tech-savvy. New ways of delivering knowledge and measuring learning outcomes have opened up tremendous opportunities for serious transformations in curriculum development and pedagogy. It also gives access to expanding the number of students at the same time [6].

As a positive trend identified in the study of ([7], p. 7), “the incredible innovative approaches to issues faced and the resilience of the sector” is noted. Let us assume that in all the cases the sphere of education will face inevitable changes since it increased “interest of policymakers for higher education competence, everywhere around the world ([7], p. 7).

Schleicher writes that to stay relevant, universities will need to reinvent their learning environments in order for digitalization to expand and complement the relationship between students and other teachers [2].

In the experimental group, in which the self-timing of the use of time was carried out, there were only 18% of students who applied an intensive model of time use and used distance learning to redirect the time spent on additional investment in their own human capital. This subgroup of students consisted mainly of students living independently with minimal contact with their families. This category also included students living in the suburbs and actually staying at home only for a short period of sleep. Under the conditions of restrictions, these guys already in the first year had additional employment and additional studies, and in the vast majority of cases, they came with this model from school. They had time spent on commuting, but almost no losses.

Additional resources of time have been gained by reducing sleep time and unproductive losses. The time spent on hobbies was practically not reduced, since almost all the students in this group devote this time to keep fit. There is an interesting fact about time spent on communication with friends—this item has not been reduced. The guys explain that their friends are their environment from main and additional studies, or new work, and communication with them is not perceived as a waste of time but is part of the life model of success. The noted time use pattern is certainly laborious. The guys note that they use this time to search for new opportunities and in the future plan to make their choice in terms of professional and personal preference.

6. Conclusions

Kara et al. [31] note that the uncertainty and limitations caused by infectious disease outbreaks are one of the most difficult situations to deal with psychologically. The need to be prepared for an unknown situation is dangerous for people, both physically and psychologically. Since it is not possible to predict a clear timeline for the end of infectious disease outbreaks, people are left with a sense of constant risk [32]. Thus, people inevitably develop an emotional response to this process.

In the early stages, the pandemic was perceived as a public health problem, but the rate of rapid infection made COVID-19 a more common and serious problem [33]. Political authorities are beginning to take precautions to reduce the rate of COVID-19 infection [3]. Travel bans and social distancing measures were the first steps taken by almost all the countries, and curfews followed in some countries.

In these circumstances, education has been severely affected as one of the main directions of the daily activities of millions of students, teachers, and parents around the world [3,34]. In most countries, schools and universities have been closed and education is provided through distance education platforms [28]. This problem has become a major issue for all the national education authorities. While distance education and other digital solutions are the best way to protect oneself from COVID-19, these methods also carry the risk of increasing educational inequality. No one considers the fact that not all the students have the same level of digital skills, computers, and Internet connection capabilities.

Tosun [27] notes that one of the most important elements influencing the success of distance education is ensuring that teachers and students have positive attitudes, behaviors, and thoughts about distance education. The recent studies on this topic are presented in the specialized literature [28,29].

The system of public administration of education in conditions of an acute shortage of time stimulated the formation of a “digital twin” of an already imperfect system of higher education. At the first stage, the digital transformation process made the disadvantages more prominent than multiplied the opportunities accumulated in recent years. For example, as a result of such a “digital transformation,” a teacher has lost the ability to directly contact, see the response of students and react quickly.

As a result of the transition to distance education in 2020, teachers were forced by their “live labor”, i.e., by additional time spent to compensate for most of the “transaction costs” of the distance mode, simulating face-to-face education. In fact, the classes, having retained the obligatory time component for the teachers (scheduled classes), stretched out in time, approaching the 24/7 mode. Additionally, since the teacher simultaneously conducts classes in several disciplines in different groups of students, it turned out that, figuratively speaking, the marathon has become an obstacle race. As a result of the “digital transformation”, attention to the teacher’s words has decreased since the total time of the audience’s attention has decreased, but at the same time, the cost of mistakes in the process of “infinite” communication with students has increased.

On the other hand, the university audience, which in many ways equalizes the students’ opportunities in obtaining knowledge, suddenly became inaccessible to all the students, regardless of any factors—their knowledge, income, social status, etc. Students have lost the opportunity to communicate directly with the main source that provides or, in modern conditions, rather moderates the learning process, i.e., with the teacher. Thus, for students wishing to learn, the learning process has become much more difficult.

Summarizing the study, one can say that the concept of the “Humboldt University”, like the concept of the “Bologna system”—a free common space for the transfer and formation of knowledge, citizenship, and the development of science—has undergone a sudden stress test for survival as a result of the reaction of politicians around the world to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The results of our, as well as other studies, demonstrate that the administrative system of the national education in developed countries has managed to cope with the organization of the transfer of teaching to the distance learning format, as they say “basically”. Although this applies only to the higher education system, since, for example, the results of social experiments on the school system turned out to be much less acceptable to society—the children had to be returned to school. With students and teachers, everything turned out to be somewhat more complicated.

For teachers, the transition to distance education meant an increase in the duration of working hours with a simultaneous loss of direct contact with students. The exclusion of communication in the classroom has strengthened the arguments of those professors who argue that the university should not be compared to a plant or factory, and students should not be compared to material semi-finished products. Professors, remaining living people, suddenly began to communicate with “black windows” on the computer screen, the reaction of which became unpredictable, the feedback was difficult to verify, the authenticity of knowledge was almost unverifiable [35].

For students, the loss of contact with the teacher has reduced the already not very high (with a practically universal opportunity for higher education) incentives to learn, i.e., for those who would like to learn, the learning process has become very difficult, for those to whom the joy of learning seems to be a distant abstraction, it turned out to be much easier to imitate the acquisition of knowledge.

At the same time, the students found themselves in an equally, but differently difficult situation. Even those factors that we did not investigate, but only mentioned—the inequality of technical capabilities, the loss of face-to-face contact with peers, a decrease in the development of socialization—plus restrictive measures by the state led to an increase in anxiety and depression. Moreover, the severity of the “quarantine” was directly proportional to the growth of psychological problems. Students, locked “at home,” plunged into the abyss of anxiety and depression. Students of another country, where the severity of the state in relation to the isolation of the population was demonstrated to a lesser extent, were left to themselves. Their level of anxiety and depression turned out to be lower, but this also did not have a positive effect on the learning process.

Obviously, the centuries-old practice of scheduled classrooms with time blocks should be revisited for classical universities. It can also be assumed that simply implementing the experience of such distance education platforms as Coursera and other organizers of massive open online courses is also not a panacea or a turnkey solution. Moreover, the mechanical combination of massive open online courses and classroom activities is unlikely to have a synergistic effect either.

The educational community is now not just faced with defining new learning formats, but rather with defining a strategic choice of path. Universities that emerged as a guild form in the Middle Ages and transformed in the 19th and 20th centuries into factories for the mass production of engineers and managers are now again on the verge of change. Digital transformation in this sense opens up incredible opportunities for the development of universities. Those of them who take leadership positions will be able to become global centers of education since the possibilities of the Internet allow this to be fully realized.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.D. and I.K.; methodology, I.D., Y.P. and I.K.; software, I.D.; validation, Y.P. and S.B.; formal analysis, Y.P.; investigation, Y.P.; resources, I.D. and I.K.; data curation, I.D., Y.P. and I.K.; writing, I.D. and I.K.; visualization, I.D.; supervision, I.D.; project administration, I.D.; funding acquisition, Y.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Link to the teacher’s questionnaire in Russian: https://forms.gle/BcUsdquC2DEt2oDq5 (accessed on 10 May 2021); Link to the students’ questionnaire in Russian: https://forms.gle/9W3QyyCedvAaUbLfA (accessed on 10 May 2021).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Correction Statement

Due to an error in article production, several article preparation template sentences were included in the initial version of this publication. This information has been removed and the manuscript updated. This change does not affect the scientific content of the article.

Appendix A

Distance learning: pros and cons.

This survey is conducted with the purpose of assessing the attitude of teachers and students to distance learning. Two versions of the questionnaire are used—the paper one you are reading now, and the electronic one in Google Docs. You can choose which form is more convenient for you to work with.

Please take some time to share your feedback in order to help students and teachers who will be using distance learning. It is very simple to do this: do not skip a single question, just select the answer option that suits you.

Thank you!

Teacher survey

Please introduce yourself:

* Required

1. Age *

○ 25–35 years old ○ 56–65 years old

○ 36–55 years old ○ Over 65 years old

2. Gender *

○ M

○ F

○ Do not want to respond

3. Teaching experience *

○ Up to 3 years ○ 16–25 years

○ 4–9 years ○ Over 25 years

○ 10–15 years

4. Country *

○ Russia

○ Other (specify please): _____________________________________________

5. Teaching area *

○ Economics and Management ○ Legal

○ Natural science ○ Humanitarian

○ Information

6. Do you lecture? *

○ Yes

○ Yes, and I also conduct seminars

○ No, I conduct seminars only

Please continue the sentences below:

After introducing distance learning, I….

7. spend more time preparing for lectures: *

○ Yes

○ No

○ I do not prepare for the courses I taught earlier

8. spend more time preparing for seminars: *

○ Yes

○ No

○ I do not prepare for the courses I taught earlier

9. develop presentations for lectures: *

○ Yes

○ No

○ Always did presentations before

10. try to speak more accurately: *

○ Yes

○ No

11. Revised my courses to improve design: *

○ Yes

○ No

○ Yes, I planned to do it for a long time

What has changed

What has changed in the work of teachers after the introduction of distance learning

12. I believe that in distance lectures the level of knowledge is lower than in full-time education: * ○ Yes ○ No

13. I believe that in distance seminars the level of knowledge is lower than in full-time education: * ○ Yes ○ No

14. I am afraid that my classes may be posted online without my consent * ○ Yes ○ No

15. The thought that my colleagues and supervisors might visit my classes: *

○ Puts me into a discomfort

○ Does not disturb me

○ Inspires me, because they will see what a professional I am

16. Most of all in distance learning I dislike: *

○ Lack of interaction with students

○ Inability to organize discussion in groups

○ Inability to check whether students complete assignments on their own

○ Other (specify please)________________________________________

It is important for me

17. to see students on the screen during classes: * ○ Yes ○ No

18. to have a feedback from students and the ability to use interactive tools: * ○ Yes ○ No

19. The transition to a distance teaching model is what I….*

○ Like

○ Dislike

Describe, please, your impressions and wishes for the development of the distance learning system ____________________________________________________

To me it is more comfortable to work with: *

○ Webinar ○ Webex

○ Zoom ○ Discord

○ Meet ○ Other (specify please)

○ Microsoft Teams

Thank you!

Appendix B

Distance learning: pros and cons.

This survey is conducted with the purpose of assessing the attitude of teachers and students to distance learning. Two versions of the questionnaire are used—the paper one you are reading now, and the electronic one in Google Docs. You can choose which form is more convenient for you to work with.

Please take some time to share your feedback in order to help students and teachers who will be using distance learning. It is very simple to do this: do not skip a single question, just select the answer option that suits you.

Thank you!

Student survey

Please introduce yourself:

* Required

1. Your year/level in the University:*

○ 1 ○ 2 ○ 3 ○ 4 ○ 5

○ Master

2. Your gender *

○ M

○ F

○ Do not want to respond

3. Country *

○ Russia

○ Other (specify please): _____________________________________________

4. Area of your education *

○ Economics and Management ○ Social and Humanitarian

○ IT ○ Mathematics and computer science

○ Natural science, engineering ○ Other

Please continue the sentences below:

After introducing distance learning, I….

5. spend more time to be prepared for classes *

○ Yes

○ No

6. attend classes more often than before*

○ Yes

○ No

○ Attend in the same way

○ I don’t attend, as I always do

7. Most of all in the distance learning I miss…: *

○ Communication with classmates

○ Contact with teachers

○ Practical training

○ Other

8. The knowledge quality in distance learning *

○ Decreased ------------- go to the Question 10

○ Increased ------------- go to the Question 9

○ Remained at the same level

9. Why do you think the knowledge quality has been decreased?

_______________________________________________________________

10. Why do you think the knowledge quality has been increased?

_______________________________________________________________

It is important for me…

11. to see the teacher during lesson * ○ Yes ○ No

12. that the teacher make a presentation of lecture * ○ Yes ○ No

13. to get a feedback from teacher during classes * ○ Yes ○ No

To me it is more comfortable to work with: *

○ Webinar ○ Webex

○ Zoom ○ Discord

○ Meet ○ Other (specify please)

○ Microsoft Teams

Thank you!

References

- Analysis of the Russian Distance Learning Market: Results of 2018, Forecast Up to 2021. Available online: https://marketing.rbc.ru/articles/10886/ (accessed on 8 May 2021).

- The Impact of COVID-19 on Education—OECD. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/education/the-impact-of-covid-19-on-education-insights-education-at-a-glance-2020.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2021).

- OECD. A Framework to Guide an Education Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic of 2020. In OECD Policy Responses Coronavirus (COVID-19); OECD: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Shevyakova, A.; Munsh, E.; Arystan, M.; Petrenko, Y. Competence development for Industry 4.0: Qualification requirements and solutions. Insights Reg. Dev. 2021, 3, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cibák, L.; Kollár, V.; Filip, S. Measuring and evaluating education quality of future public administration employees at private university in the Slovak Republic. Insights Reg. Dev. 2021, 3, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinichenko, M.V.; Melnichuk, A.V.; Karácsony, P. Technologies of improving the university efficiency by using artificial intelligence: Motivational aspect. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2020, 7, 2696–2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IAU Global Survey Report—The Global Voice of Higher. Available online: https://www.iau-aiu.net/IMG/pdf/iau_covid19_and_he_survey_report_final_may_2020.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Besenyő, J.; Kármán, M. Effects of COVID-19 pandemy on African health, political and economic strategy. Insights Reg. Dev. 2020, 2, 630–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezk, M.R.A.; Piccinetti, L.; Radwan, A.; Salem, N.M.; Sakr, M.M.; Khasawneh, A. Egypt beyond COVID 19, the best and the worst-case scenarios. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2020, 8, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincényi, M.; Laczko, M. Influence of Brexit on Education towards Europeanism. Insights Reg. Dev. 2020, 2, 814–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strakšienė, G.; Ruginė, H.; Šaltytė-Vaisiauskė, L. Characteristics of distance work organization in SMEs during the Covid-19 lockdown: Case of western Lithuania region. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2021, 8, 210–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Fadly, A. Impact of COVID-19 on SMEs and employment. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2020, 8, 629–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razif, M.; Miraja, B.A.; Persada, S.F.; Nadlifatin, R.; Belgiawan, P.F.; Redi, A.A.N.P.; Lin, S.-C. Investigating the role of environmental concern and the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology on working from home technologies adoption during COVID-19. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2020, 8, 795–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laužikas, M.; Miliūtė, A. Impacts of modern technologies on sustainable communication of civil service organizations. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2020, 7, 2494–2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, W. COVID -19 and Online Teaching in Higher Education: A Case Study of Peking University. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 2, 113–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, P. Impact of Pandemic COVID-19 on Education in India. Int. J. Curr. Res. IJCR 2020, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, S.J. Education and the COVID-19 Pandemic. Prospects 2020, 49, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özmete, E.; Pak, M. The Relationship between Anxiety Levels and Perceived Social Support during the Pandemic of COVID-19 in Turkey. Soc. Work Public Health 2020, 35, 603–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5 (5th Edition). Ref. Rev. 2014, 28, 36–37.

- Rosen, J.B.; Schulkin, J. From Normal Fear to Pathological Anxiety. Psychol. Rev. 1998, 105, 325–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carleton, R.N. The Intolerance of Uncertainty Construct in the Context of Anxiety Disorders: Theoretical and Practical Perspectives. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2012, 12, 937–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panayiotou, G.; Karekla, M. Perceived Social Support Helps, but Does Not Buffer the Negative Impact of Anxiety Disorders on Quality of Life and Perceived Stress. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2012, 48, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davulis, T.; Gasparėnienė, L.; Raistenskis, E. Assessment of the situation concerning psychological support to the public and business in the extreme conditions: Case of Covid-19. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2021, 8, 308–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grills-Taquechel, A.E.; Littleton, H.L.; Axsom, D. Social Support, World Assumptions, and Exposure as Predictors of Anxiety and Quality of Life Following a Mass Trauma. J. Anxiety Disord. 2011, 25, 498–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCauley, M.; Minsky, S.; Viswanath, K. The H1N1 Pandemic: Media Frames, Stigmatization and Coping. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2011, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tosun, N. Distance education practices at universities in Turkey: A case study during covid-19 pandemic: Distance education practices. Int. J. Curric. Instr. 2021, 13, 313–333. [Google Scholar]

- Colaceci, S.; Zambri, F.; D’Amore, C.; De Angelis, A.; Rasi, F.; Pucciarelli, G.; Giusti, A. Long-Term Effectiveness of an E-Learning Program in Improving Health Care Professionals’ Attitudes and Practices on Breastfeeding: A 1-Year Follow-Up Study. Breastfeed. Med. 2020, 15, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, P.P.; Papachristou, N.; Belisario, J.M.; Wang, W.; Wark, P.A.; Cotic, Z.; Rasmussen, K.; Sluiter, R.; Riboli–Sasco, E.; Car, L.T.; et al. Online ELearning for Undergraduates in Health Professions: A Systematic Review of the Impact on Knowledge, Skills, Attitudes and Satisfaction. J. Glob. Health 2014, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Clark, T. COVID-19 and Management Education: Reflections on Challenges, Opportunities, and Potential Futures. Br. J. Manag. 2020, 31, 453–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, A. Positive and Negative Affect during a Pandemic: Mediating Role of Emotional Regulation Strategies. J. Pedagog. Res. 2020, 4, 484–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavel, J.J.; Baicker, K.; Boggio, P.S.; Capraro, V.; Cichocka, A.; Cikara, M.; Crockett, M.J.; Crum, A.J.; Douglas, K.M.; Druckman, J.N.; et al. Using Social and Behavioural Science to Support COVID-19 Pandemic Response. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Impact of COVID-19 on Education. Available online: https://voxeu.org/article/impact-covid-19-education (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- How Are Countries Addressing the Covid-19 Challenges in Education? A Snapshot of Policy Measures. Available online: https://gemreportunesco.wordpress.com/2020/03/24/how-are-countries-addressing-the-covid-19-challenges-in-education-a-snapshot-of-policy-measures/ (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Pitoňakova, S. Public Relations as a Part of the Presentation for Teachers. In Высшее Гуманитарнoе Образoвание XXI Века: Прoблемы и Перспективы: Материалы Одиннадцатoй Междунарoднoй Научнo-Практическoй Кoнференции; ПГСГУ: Самара, Russia, 2016; pp. 172–183. ISBN 978-5-8428-1068-0. Available online: https://fhvuniza-my.sharepoint.com/:b:/g/personal/slavka_pitonakova_fhv_uniza_sk/Ea0cROFStstEpWsNmIqnqxYB7Kln88jB9_q5ZxvedBheyw?e=oKOiwr (accessed on 10 May 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).