1. Introduction

The crisis of representative democracy triggered democratic innovations [

1,

2]. Endeavors for the qualification of democratic systems and democratic reforms are high on the agenda. Political participation plays an important role in democracies [

3]. With the Rio conference in the 1990s, the Local Agenda 21 strategies strengthened a new trend towards more deliberative political participation, focusing on sustainability. It was also a trigger for social innovations and a wave of more civic engagement and communal self-help in the late 1990s. A broader participatory space with the democratic innovations as a “deliberative turn” [

4] can be testified to in several new participatory instruments in the invited and invented space [

5]. In the invented space, new participatory instruments are initiated by civil society (bottom up) often in the form of demonstrations. In the invented space, the state offers new channels to extend the participatory space often to include new interest groups and to put new issues on the agenda. Nevertheless, criticism of participatory democracy and demands for more elite-centered epistocratic governance and a stealth democracy also became louder [

6,

7].

The main focus here is on Germany. Germany will be analyzed as one of the frontrunners in two aspects. Since the 1980s in Germany, new parties (Green) have been highlighting policy issues such as sustainability and climate change, and new social movements have demanded new economic and infrastructural policies at the national, regional, and local levels [

8]. Secondly, the German federal system highlights the role of multifunctional municipalities and attributes numerous decision-making processes to the local level [

9]. Here democratic participatory innovation plays an important role.

In Germany, this is evident through the development of the Green Party, which took up the new cleavage in the 1980s, and its growing importance firstly at the local level and later at the regional and national level. After the nuclear disaster in Fukushima 2011, the German Green Party gained more members of parliament and became part of government coalitions in different Länder. However, with the push by the Fridays for Future movement in the late 2010s, the Green Party has also been able to increase both its membership and its voters. The ecological transformation of society is deeply embedded in the Green Party manifesto. However, ecological issues also became relevant topics for most other parties, with the exception of the right-wing populists.

In the area of democratic innovations, another global trend has appeared. The local level in particular was often seen as a laboratory for new participatory instruments. German cities had implemented some participatory instruments on conflict resolution in the 1970s. With the direct election of mayors at the local level, new referendums, and new forms of participatory budgeting in most European countries, new deliberative participatory instruments were also high on the agenda. In Germany, this can be seen as a reaction towards political scandals (Barschel affair) as well as good experiences with round tables in the process of German unification. German cities in the 1990s were characterized by the implementation of new instruments such as referendums at the local level, new voting systems such as cumulative voting and panache voting, direct elections and recalls of mayors, and new advisory boards for particular interest groups involving elderly or disabled citizens. To mitigate strong protests against some infrastructure projects, such as the railway station “Stuttgart 21,” in the 2010s, a number of deliberative participatory instruments such as participatory budgeting processes were introduced in most large German cities. In the 1990s, Germany introduced and “imported” a number of democratic participatory innovations, reinvigorating the local representative democracy (see, for example, the participatory budgeting in Porto Alegre). In Germany in the 1980s and even more in the 2010s, demonstrations by large social movements such as Fridays for Future pushed most political parties towards a stronger focus on climate change and sustainability [

10].

Political participation and sustainability, which means questions of ecological policies, climate justice, and change, are strongly intertwined. We will analyze where political participation focuses on sustainability topics. In the following, we will analyze the broad range of participatory instruments within the political system using the participatory rhombus model. After a short description of participatory instruments, we will concentrate on the deliberative participatory tools. It will be argued that ecological transformation is strongly related to new participatory instruments. Ecological transformation includes policies that reduce climate change such as the sharing economy, the development of renewable energy production, etc. For this transformation, on the one hand, broad legitimacy and support by the citizen seems to be necessary. On the other hand, the sharing economy, for example, must be based on innovative forms of community development. Both are dependent on participatory instruments and democratic innovations. How do citizens and local councilors evaluate these different forms of participation in democratic innovations? The councilors’ survey focuses on the question of the acceptance of these new participatory instruments in the field of sustainability.

2. Typology and Definitions

Political participation is defined as an individual and organized act to influence political decision-making. Democratic innovations focus on political participatory instruments, electoral reforms, etc. In contrast, civic engagement and all forms of communal self-help (for example, on climate change initiatives in the neighborhood) predominately concentrate on producing certain services (e.g., in a sharing economy) and, in general, do not include any decision-making competencies [

11,

12]. This social innovation is not primarily oriented towards the influence of decision-making, but focuses on civic engagement as co-production. Political participation and civic engagement are interdependent, but have to be differentiated. Nevertheless, political participation can have an essential social function, especially in social capital development (for social innovation see [

9]). Furthermore, in the field of ecological transformation, there seems to be an overlapping of political participation and civic engagement.

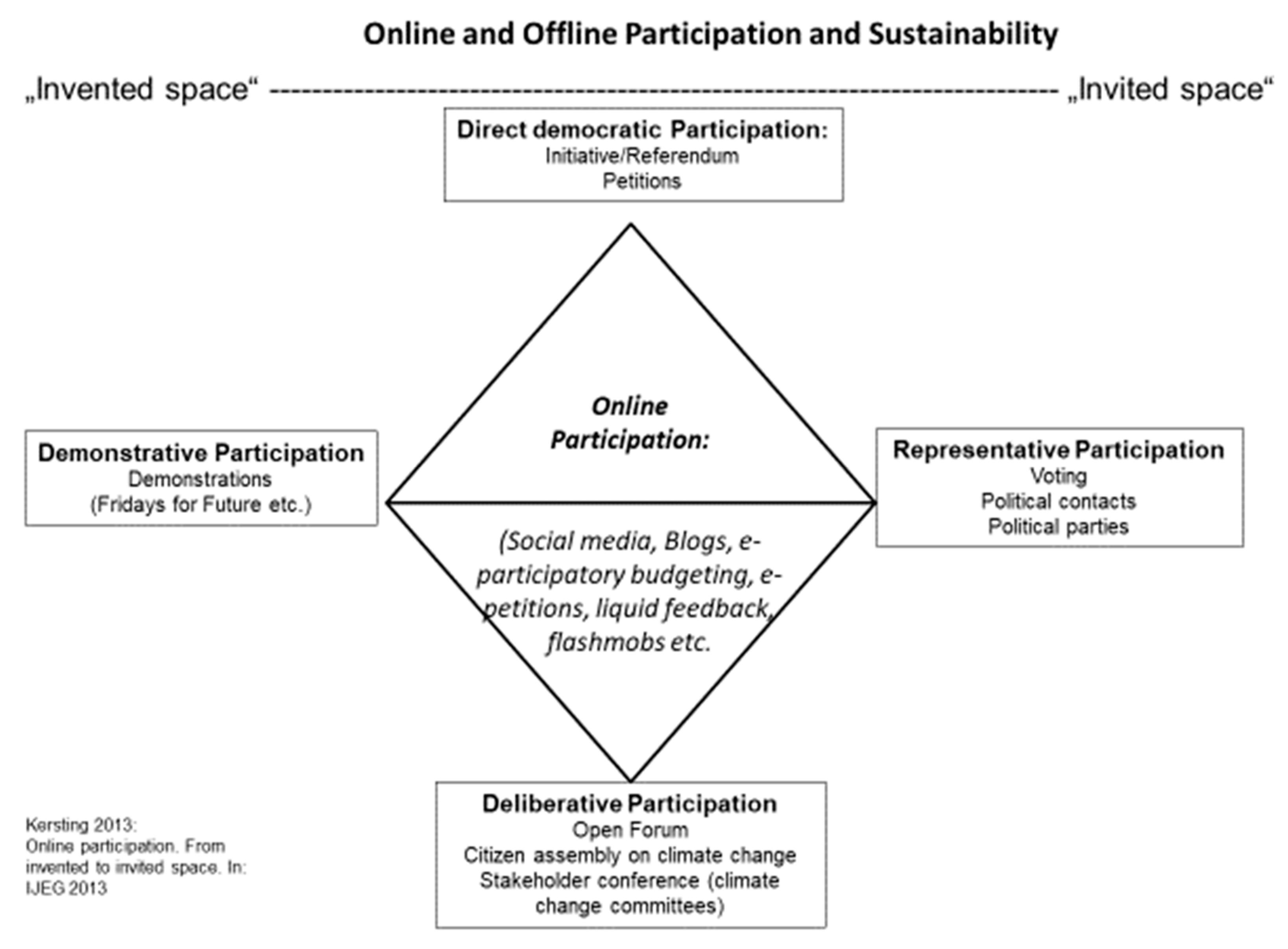

On the one hand, participatory instruments can be developed bottom-up by civil society to create an invented space as the political arena [

5]. Participatory instruments can be implemented top-down by local, regional, or national governments to include citizens and open the invited space. They can have a binding role, such as in elections and referendums in “numeric democracy” (see [

13]), and they can be more consultative and more discursive, for example, in open forums based on self-selection, in stakeholder conferences with organized interest groups, and in randomly selected citizen assemblies, or more expressive, for example, in demonstrations.

In the following, we divide online participation from offline participation. We often find a combination of online and offline participation, different types, and another sequencing of these tools (see the directly deliberative democracy (DDD) project). Instruments can be initiated by civil society (invited space) and top-down planning (invited space, which can be binding or not binding, formal or informal, and expressive or decisive [

5].

The political arena is divided into different spheres: the representative participatory sphere, the direct democratic participatory sphere, the demonstrative participatory sphere, and the deliberative participatory sphere (see the participatory rhombus in

Figure 1). These four spheres encompass all forms of participation. In the following part, we will define the instruments and show where sustainability became an important topic in political participatory instruments. In all these spheres, climate change and transformation in sustainability become more important on the agenda.

2.1. Representative Participation

In the representative sphere, participation encompasses elections and direct contacts with political candidates and political administration, predominately. In this area, it can be shown that new Green political parties have played a more and more critical role in many countries [

14]. In Germany, the Green Party entered local, regional, and national parliaments in the early 1980s and became a coalition partner in a number of the local and regional governments in the 1990s and 2000s. In particular, in the late 2010s, it can be shown that sustainability policies were more and more supported not only by the Green Party but also by most relevant political parties except the right-wing populist party.

2.2. Direct Democratic Participation

In the direct democratic sphere, referendums and petitions are important instruments of this numeric participation. Parliamentary petitions are used at the regional and the national level (e.g., Bundestags-Petitionsausschuss) [

15,

16]. Additionally, civil society organizations use online petitions, which focus on topics of sustainability, in the invented space (e.g., Change.org, MoveOn, Campact) [

17].

In the 1990s, after Baden-Wuerttemberg, all other regions implemented local initiatives and referendums with different thresholds and somatic exclusions. Around 4107 referendums took place in Germany between 1956 and 2009 at the local level (another 4000 were stopped beforehand, but altogether there were 8100 processes) [

18]. Most of the overall 8100 direct democratic processes were not implemented by citizens as citizen initiatives but rather by the council or the local administration. Therefore, over 50% took place between 2003 and 2019. Because of different legislation and thresholds, regional effects occurred. It can be shown that 40% of all processes took place in Bavaria.

Town planning was different in different regions because some regions have thematic exclusions and do not allow town planning issues in local referendums. Other ecological policies were often on the agenda, with 16.2% constituting traffic and transport issues, and economic projects such as new hotels, shopping centers, and wind parks (17.8%). In fact, most topics were high on the agenda except the area of social development and education (19.7%) and amalgamations in territorial reforms (9.7%), cultural projects (4.0%), and governance topics (2.4%). Most other local referendums had a strong influence on sustainability.

In some cases, there was an indirect effect, for example, when local tariffs for the duration of garbage collection were on the agenda. The results of these referendums in the area of “re-communalization” showed a positive effect on sustainability policies.

Nevertheless, all the results show a mixed picture. In general, referendums can be regarded as more “structurally conservative.” On the one hand, large new infrastructural projects such as airports, highways, etc., were often blocked. On the other hand, new green energy projects, such as turbines and wind parks, were stopped.

2.3. Demonstrative Participation

In Europe, ecological political parties often developed from strong social movements in the 1970s and early 1980s. This is quite obvious in the German case, where strong fundamentalist positions and even strategies characterized the Green Party, often as extra-parliamentary opposition (“Ausserparlamentarische Opposition,” APO). There was, and in certain regions there still is, a strong link between economically left-wing social groups and ecological parties [

19]. In the early 1980s, the development of the Green Party was strongly connected to the peace movement and large demonstrations such as the one in 1982 against NATO decisions in Bonn. Furthermore, green parties firmly focused on direct and deliberative democracy.

In the following years, strong inclusion into the parliamentary system became apparent. In the 2010s, new social movements and protest were developing in larger European cities, such as “Anonymous” in Madrid [

20]. In Germany, strong protest against infrastructure projects such as the railway station and shopping mall project “Stuttgart 21” took place. In the late 2010s, with the movement Fridays for Future, the younger generation, including striking pupils, became highly involved in politics. Their focus is on the World Climate Conference (COP-21) results in Paris in 2015), on the end of coal power stations, and on new regenerative energy. Here it can be shown that this movement strongly influences all political parties. Fridays for Future has highly decentralized but digitally connected branches, and it uses decentralized weekly demonstrations and online networks to influence local, regional, and national politics. The social movement is related to the protest against large infrastructure projects to develop coal mining (in the late 2010 Hambacher Forst) and new highways (Highway 21: A47). Besides demonstrations, consumer boycotts, strikes, and digitally organized flash mobs, etc., are characterizing these social movements’ activities. From a global perspective, these movements are robust in other European countries such as Sweden, France, the UK, and Italy, as well as in Australia, Brazil, etc.

2.4. Deliberative Participation

In the 1990s, new deliberative instruments were implemented. Here, already existing formal local council commissions and informal advisory boards were added, especially at the local level. This deliberative turn [

4] brought three different types of deliberative instruments [

21]. Already existing advisory boards were redeveloped. In neo-corporatist contexts, these informal instruments incorporated existing organized interest groups. They were predominantly administered by the local administration and chaired by the mayor or the town clerk. New modern advisory boards try to incorporate broader new social movements from civil society. These advisory boards predominantly focused on particular interest groups and topics. Furthermore, some of them were directly elected. They are chaired by a civil society representative, which is very important for agenda-setting and influence.

Therefore, child and youth parliaments, advisory boards for disabled citizens, and advisory boards for seniors or migrants have been implemented. In the area of sustainability, advisory boards for ecological topics were implemented in the new millennium. Some of them incorporated representatives from the already existing Local Agenda 21 groups, developed in the years after the Rio conference in the 1990s [

22]. But in the 1990s, additional experts on climate change were directly included on these new stakeholder boards (local climate change committees).

In the 1990s, the new strategy incorporating civil society also opened to members of the public. In these open forums, ordinary citizens were invited to participate. It can be shown that citizen participation often mirrors the already existing inequality and the political participatory divide. Although anyone could take part in numerous offline participatory instruments, marginalized social groups with low levels of resources such as time, knowledge, and finances did not participate. These open forums often focus on important local ecological topics such as new transport systems within cities, town planning, traffic, and prominent infrastructural instruments such as wind turbines. In some of these participatory instruments, “Not in my backyard” attitudes became obvious. Affected citizens protested against these infrastructure projects. This conservative bias is similar to direct democratic initiatives. In fact, referendums can often be seen as a result of social movements and deliberative processes.

At the local level, after the reforms of the 1990s, more deliberative instruments as well as more digital instruments were implemented, particularly in the early 2000s. Starting in Puerto Rico, the participatory budgeting processes focused on the distribution of financial resources in sub-municipal contexts. This instrument became very popular in Brazil, in Latin America, and further on in Southern Europe, in particular in Spain and Italy [

23]. It was also used in all larger German cities but with different characteristics. In Germany and in a couple of other countries, participatory budgeting was implemented slightly differently. In Germany in the 2010s, it was more a management tool and was predominantly a digital electronic suggestion box. Citizens were allowed to make suggestions for smaller projects, which were handed over to the administration. After an administrative evaluation and scrutinization, these instruments were transferred to the city council, which had the final say. Participatory budgeting processes in Germany did not have their own budget, but it was incorporated in the municipal budget decision-making process. Secondly in Germany, after some quite disappointing tests of face-to-face town hall meetings to discuss the budget, most administrations and mayors decided to run participatory budgeting predominantly as an online participatory instrument. Thus, individuals could make their suggestions online and then in the second phase they were evaluated online by members of the public before they went to the administration of the city council. This hindered and stopped intensive deliberations but also led to number of smaller and less cost-intensive projects, because broader forms of planning were made impossible. In the following years, because of the local financial crisis, it was not even allowed to make suggestions for new projects anymore, only suggestions for saving financial resources. Because of this, participatory rates and turnaround in participatory budgeting processes became very low. In the following years, a couple of cities stopped participatory budgeting altogether. In some other cities it was revitalized by a slight change in its implementation. In some German cities, so-called “citizen budgets” were implemented. This instrument is more comparable to the original Porto Alegre participatory budgeting processes, because here a small but substantial budget is reserved for neighborhood projects.

In recent years an even older instrument experienced a renaissance. The first smaller test, with participatory instruments based on sorting and randomly selected participants, was implemented sporadically in the 1980s and 1990s [

24]. Deliberative polls could be regarded as citizens’ assemblies [

25]. With its best practices at the national level in Ireland and the local level in Belgium and other countries, citizens’ assemblies (mini publics, citizen juries, deliberative polls, Planungszelle) were implemented not only at the national level but also locally. Therefore, with the wave of citizens’ assemblies and with their new components (from mini public to citizen assembly) and changes, citizens’ assemblies could be regarded as real democratic innovation. At various weekend workshops, between 50 and 160 randomly selected members of the public were briefed by a neutral set of experts. The group discussed important topics before they voted on actions and suggestions for the legislative or executive body.

In France, following the Yellow Vest movement, a citizen assembly on climate change was implemented in 2019 at the national level. Similar processes followed this in Scotland, the UK, and other countries. In Germany, the federal parliament supported the first national citizen’s assemblies that focused on the future of democracy and governance role in the global context. Civil society groups demanded a focus on sustainability, but because of upcoming elections for the 2021 German Parliament it was denied. In May 2021 a citizen assembly (Bürgerrat) on sustainability was initiated by different civil society groups. At the local level, citizens’ assemblies mostly focused on areas of town planning and developed often detailed reports for the city council.

3. Citizen Perceptions of Participatory Instruments

It could be argued that the use of participatory instruments is related to its acceptance [

11,

26]. Low voter turnout is regarded as a dissatisfaction with representative democracy. Participatory instruments in the four participatory spheres are characterized by different rates of participation.

The “numeric democracy” instruments, such as elections and referendums, have by far the highest turnout (for numeric democracy, see [

9]. Although the voter turnout in local elections is decreasing in most countries, it can be shown for Germany that there is still a relatively high voter turnout with around 50% of eligible voters. In local direct elections of mayors, the voter turnout can fall to one third of the eligible voters in cases where parallel elections are not taking place. In contrast, this turnout is even 10% higher in regional and 20% higher in national elections [

27]).

In addition to the direct election of mayors, local referendums have been taking place in all German Länder since the 1990s. There is a widespread voter turnout depending on the size of the city as well as the importance of the topic. However, it can be shown that even where participation rates are low, more than one third of citizens still take part in referendums. Regional referendums are parallel to regional elections and have a voter turnout of around two thirds of the eligible voters.

In local demonstrations, only a small part of the whole population is involved (see Stuttgart 21). The biggest demonstration in Germany in the early 1980s had around 200,000 participants (for the peace movement, see [

28]). Nevertheless, Fridays for Future demonstrations in 2019 were held in different cities simultaneously and could motivate some thousands of participants in each city. Here the number of participants increased with online instruments. Nevertheless, demonstrative participation cannot enlist as many citizens as elections and referendums. This discrepancy and participatory divide are even higher when it comes to deliberative democracy. Open forums in some cities and suburbs only attracted a small number of people or a few hundred. When it came to stakeholder conferences, new advisory boards included in general between 10 and 50 people. Citizens’ assemblies (mini publics) with randomly selected participants had between 50 and 150 participants [

29].

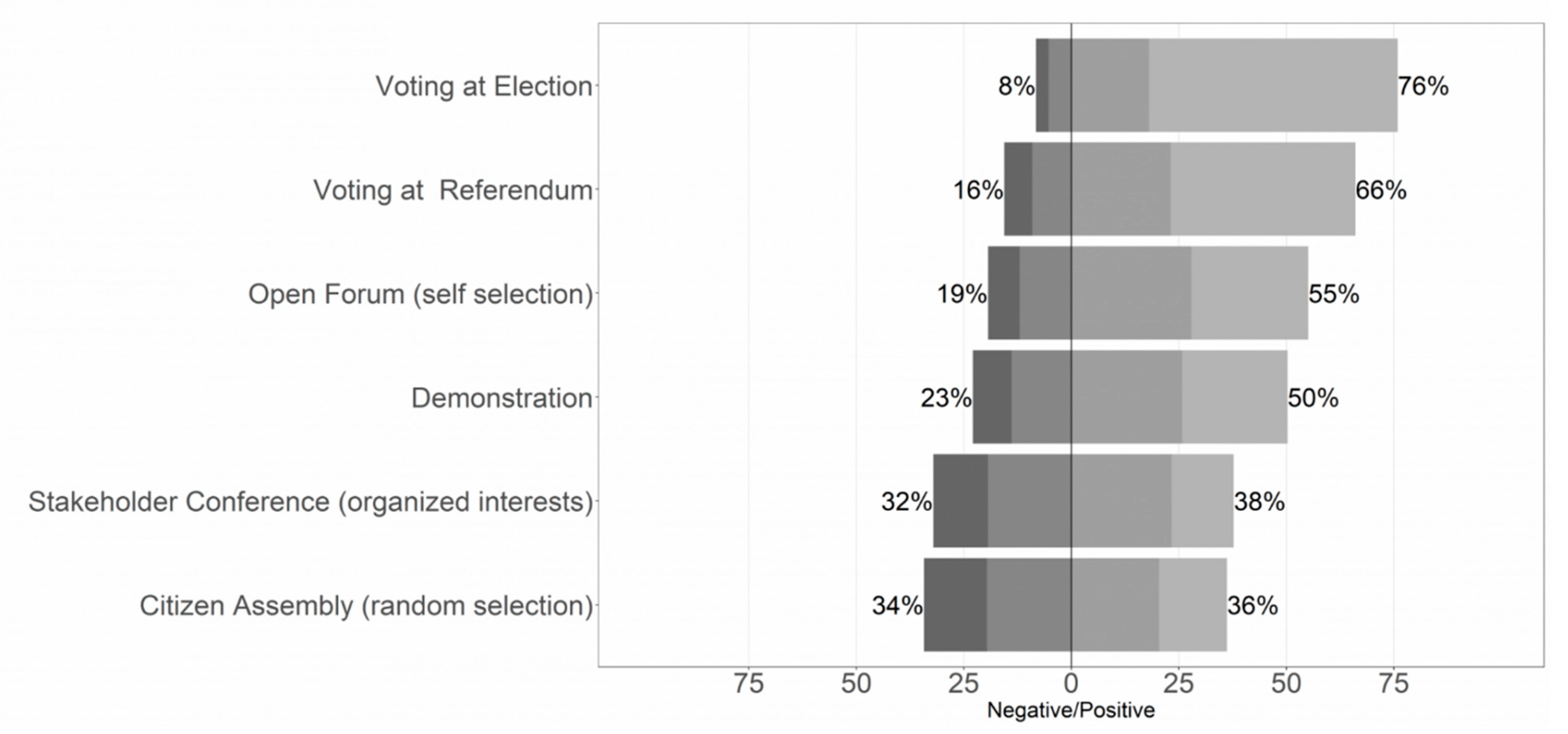

Before the councilors’ acceptance of participatory instruments is discussed, the attitudes of the citizens will be presented briefly (see

Figure 2).

In a survey in 2019, 2000 citizens were asked about their opinion on participatory instruments in an online survey. The analysis showed that the data were representative in the important aspects of gender, education, and age groups’ political party affiliations. The survey was a replication of the earlier telephone survey in 2014 in 27 cities in Germany with 2700 citizens [

21,

30].

The evaluation focused on the process, its efficacy, and its legitimacy. At first glance it does not seem remarkable that more than 76% of citizens regarded local elections as most important for the decision-making process. Only 8% saw local elections negatively and a middle range of around 14% were indifferent. This is important regarding a lower voter turnout and a decrease at the local level.

Referendums were also seen as important, with two thirds of citizens supporting them, despite the low turnout and some controversial referendums (see referendum on schools in Hamburg, on Olympic Games in München, on Brexit in UK, etc.).

Demonstrations were lower on the list of preferences. Here half of the citizens regarded this as an important and influential positive instrument. Nearly a quarter of the citizens were critical of demonstrations, which were regarded as an unconventional participatory instrument in Germany for a long time [

32].

When it came to the deliberative instruments, the three types of participation were evaluated differently. Open citizen forums such as town hall meetings based on self-selection were regarded as the most positive deliberative instrument. Here, more than half of citizens regarded these open conferences positively. A fifth of citizens viewed them critically.

Advisory boards for stakeholders were regarded positively by more than a third of the citizens. Meanwhile, nearly one third criticized these stakeholder conferences.

Citizens’ assemblies are not well known among the general public as a whole. Nevertheless, it seems that these are seen more critically. More than a third of the population supports these new instruments, one third is indifferent, and one third is (very) critical.

Participatory instruments broaden the chance for participation, but it is often mentioned that citizens’ demands are critical and too high. It is apparent that this is not just a wish list where citizens demand as many instruments and as much as possible. The list shows a clear differentiation.

Citizens seem to regard the binding decision in elections and in referendums much higher than the more consultative ones. Elections and referendums do not require a high investment of time and other resources (knowledge), but offer an influential vote. Traditional participatory instruments from the neo-corporatist system such as stakeholder conferences with influential representatives of organized interest groups are criticized because citizens are excluded. The same aspect applies to citizens’ assemblies with a selection by a lottery. The chances of being selected are not very high, although these instruments are regarded as a stimulator and incubator for broader discussions.

4. Acceptance of Participatory Instruments by the Councilors

Turnout and the rate of representation ca be regarded as one indicator of the acceptance of participatory instruments. Acceptance includes the evaluation of the process (input legitimacy) as well as satisfaction with the results (outcome, impact, output legitimacy). In the following, the acceptance of the different participatory instruments within the local politicians is analyzed. In a survey in June/July 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic and three months before the local elections, local councilors in the biggest German “Land,” North Rhine-Westphalia, were asked to evaluate local participatory instruments (see

Figure 3). In this survey all cities over 100,000 inhabitants were included, as well as the same number of medium-sized cities (20,000–10,000) and small-sized cities (−20,000). The response rate was 25% and altogether 1800 people responded. The evaluation concentrated on the participatory process itself as well as its effects. The survey was a replication of the earlier survey in 2014 [

30]. In the following, participatory instruments from the different participatory spheres are analyzed. The research question concentrates on the general acceptance by the councilors as well as different opinions in small and large cities, in different age and gender groups, as well as in different partisan groups.

When it came to elections, it is obvious that more than 84% of the councilors strongly highlighted the importance of local elections for the decision-making process. Only 4% saw local elections negatively. The middle range of 12% was indifferent. Analyzing the different political parties, it is obvious that especially the more established parties had a slightly stronger focus on local elections. Nevertheless, all councilors regarded local elections as highly important.

Local referendums were also supported by more than two thirds of the councilors. A total of 69% regarded local referendums as (very) positive, whereas only 9% had more negative attitudes towards local referendums. There were significant differences between the different political parties. In the conservative party (CDU), only 61% regarded local referendums as positive and around 11% as negative, whereas in the Green Party more than three-quarters (79%) supported local referendums. At the local level there was strong support for direct democracy within the Green Party.

Demonstrations were seen positively and as a positive and effective instrument by only 46% of all councilors. There was a big discrepancy between the political parties. In the conservative party (CDU), only a minority (23%) saw demonstrations as positive and a majority (32%) as negative. The supporting group was much bigger in the Social Democratic Party (SPD), where 51% saw demonstrations positively and only 13% critically. In the Green Party, as many as 70% evaluated demonstration as (very) positive and only 7% evaluated them negatively.

In the deliberative sphere, the acceptance of the three different types of deliberative participation, i.e., open forums, stakeholder conferences (advisory boards), and citizens’ assemblies, varied among the parties (see

Figure 4). Deliberative instruments with open access and self-selection such as open forums, future search conferences, town hall meetings, and sample conferences were highly accepted. Two thirds (63%) of the councilors in general supported these instruments and only 12% rejected them. However, within the Green Party, as many as 76% strongly supported these open dialogical participatory instruments. This support was much lower (55%) in the conservative party (CDU).

Participatory instruments for stakeholders such as roundtables or advisory boards and commissions for particular interest groups were supported by 47%. Meanwhile, 18% saw them as not very effective or positive. Here political parties were more similar in their evaluation. A total of 54% of councilors in the Green Party and 45% in the conservative party (CDU) saw them very positively.

Finally, the citizens’ assemblies (mini publics, citizen juries, Planungszelle) using random selection and sortition was supported by the majority. A total of 39% saw this relatively new instrument positively, and 26% criticized it. However, there were strong party discrepancies. Within the Green Party, 56% supported citizens’ assemblies and only 16% evaluated them negatively. In the conservative party (CDU), only 29% supported citizens’ assemblies and 33% rejected them.

5. Conclusions

Since the last millennium, it can be shown that two important political megatrends have been visible. On the one hand there is a strong tendency towards democratic innovations and new forms of participatory instruments. On the other hand, climate change, sustainability, and ecology policies have been pushed tremendously since the 1980s. In all spheres of participatory instruments in Germany (representative, direct democratic, demonstrative, and deliberative), sustainability is high on the agenda and the climate change movement, political parties, and individual actors play an important role in demanding more democratic innovations and more direct and deliberative forms of participation. Germany was one of the frontrunners in the development of green political parties. However, it was late in the implementation of new instruments (participatory budgeting), but is learning participatory innovations from the Global South and from other European countries.

In the representative sphere, green political parties are playing an important role. Direct democratic instruments are used by civil society groups as well as ecological parties. Referendums are related to critical infrastructure such as power stations, wind turbines, and highways. Demonstrations such as Fridays for Future are important channels to express protest, and in the deliberative sphere all three types of participatory instruments can be seen: open forums with self-selection, citizen assemblies based on sortition, and stakeholder conferences that focus more on sustainability and include organized ecological interest groups. Deliberative participatory instruments (round tables) focus on big, highly criticized infrastructural projects such as railway stations (Stuttgart 21).

Our empirical research shows that citizens want more of a say in the decision-making process. They highlight the representative democracy and elections. However, there is a high demand for direct democratic referendums as well as for deliberative participatory instruments. Here open forums are preferred by a clear majority. Only a smaller majority supports stakeholder conferences as well as randomly selected citizen assemblies. Further research in more countries is needed to analyze whether this is related to different chances to participate in these instruments.

In the late 2010s, only a few local councilors were resistant to and critical of new participatory instruments that give broader power to the direct participation of the general public. The surveys show that in general, the majority of the councilors regarded most of these instruments much more positively and saw them as a kind of add-on for local representative democracy. However, local elections and referendums were regarded as the dominant, most important instrument by the majority of all councilors. Most councilors supported more deliberative forms of participation as well as even more unconventional involvement such as participation in demonstrations, etc.

However, a significant correlation between party membership and the evaluation and acceptance of participatory instruments is obvious. Younger local councilors, particularly female councilors, seem to be more open to new forms of local participation and the new deliberative participatory space. This includes not only the invited space implemented by local administrations in order to channel local protests. It also encompasses the bottom-up, more informal participatory instruments within the invented participatory space. The new instruments also have a strong political party bias. Our survey data show that more councilors from the Green Party strongly supported more deliberative and direct democratic instruments. In the conservative parties (CDU/CSU) there was also a majority in favor of the new participatory instruments, but there was still a group of often older councilors who rejected this kind of participatory democracy at the local level.

All councilors in all political parties saw the dominant and important role of voting in elections and referendums. When it comes to the other participatory instruments it becomes clear that the acceptance of the instruments differs from party to party. Political demonstrations were strongly supported by the Green Party and rejected by a majority within the conservative parties, whereas the Social Democratic councilors were split. Within the deliberative participatory instruments open forums found the greatest acceptance. Roundtables for stakeholders were also high on the agenda, and in third place—and often not well known—were the new instruments of randomly selected citizens’ assemblies.

It can be argued that political parties have, over the years, learned how to engage in new forms of participatory instruments. Although political parties still play the most important role in the elections, they often play a relevant role in referendums. Sometimes they use these instruments as a kind of second channel or a last resort in the decision-making process. Some referendums are implemented by political opposition parties in cooperation with civil society groups. The same strategic engagement can exist in deliberative participatory instruments. It can be shown that political parties play an important role in local open forums and townhall meetings, where they often dominate the discussion. The relatively new instrument of randomly selected members of civil society in citizens’ assemblies can significantly reduce the influence of political parties, because neither every citizen nor every politician may be selected. Because of sortition, members of the political parties are not directly included in this process. Members of political parties may be invited as experts to show their political positions, but they are not part of the group developing a final report. It could be argued that this is a general reason for the high skepticism of councilors towards citizens’ assemblies.

Finally, it can be concluded that different forms of participation are closely related to sustainability. Germany has learned from other countries and in particular from the Global South (e.g., Brazil). However, in Germany, these participatory processes are strongly related to the local level. Cities have become a laboratory for an innovative participatory space. In other countries, such as Ireland, France, the UK, Belgium, Italy, and Portugal, new participatory instruments play a more important role at the regional and the national level.

New participatory instruments get support from citizen and politicians. All these instruments may be important for legitimate ecological transformations and mobilizing civic engagement in the field of sustainability.