Co-Housing Response to Social Isolation of COVID-19 Outbreak, with a Focus on Gender Implications

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. COVID-19 Outbreak

1.2. Social Distancing

1.3. Co-Housing

1.4. Housing, Open-Air Spaces and the COVID-19 Outbreak: State of the Art and the Research Question

1.4.1. Open-Air Spaces

1.4.2. Housing

1.5. Research Question

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey Design

- Baseline characteristics: referring to baseline characteristics of the participants (age and gender) and of their own community (name, country, region, dimension, and context). These questions had the goal of understanding the distribution of the population taking part in the survey and to draw people to the questionnaire.

- Social interaction: questions to describe the variation in social interaction, comparing pre-COVID-19 and COVID-19 periods, with particular emphasis on the variation of relations within and outside the community.

- Spatial considerations: questions to describe the variation in the role that private, shared, and open-air spaces have in co-housing community life.

2.2. Co-Housing Communities: Definition and Selection

2.3. Survey

- Name of your co-housing CommunityOpen question

- CountrySelection from: Canada, USA, UK, Spain, Australia, and New Zealand

- State/Region where your co-housing community is locatedOpen question

- Number of individuals in your communitySelection from: 21–30; 31–40; 41–50; more than 50

- Which picture best represents the context of your community?Selection from pictures: Rural; Sub-urban; Urban; Historic Center; Outskirt; Forest

- Your ageSelection from: 18–30; 31–40; 41–50; 51–60; 61–70; older than 71

- Your sexSelection from: Female; Male; Prefer not to say; Non-Binary; Gender nonconformingSocial interaction

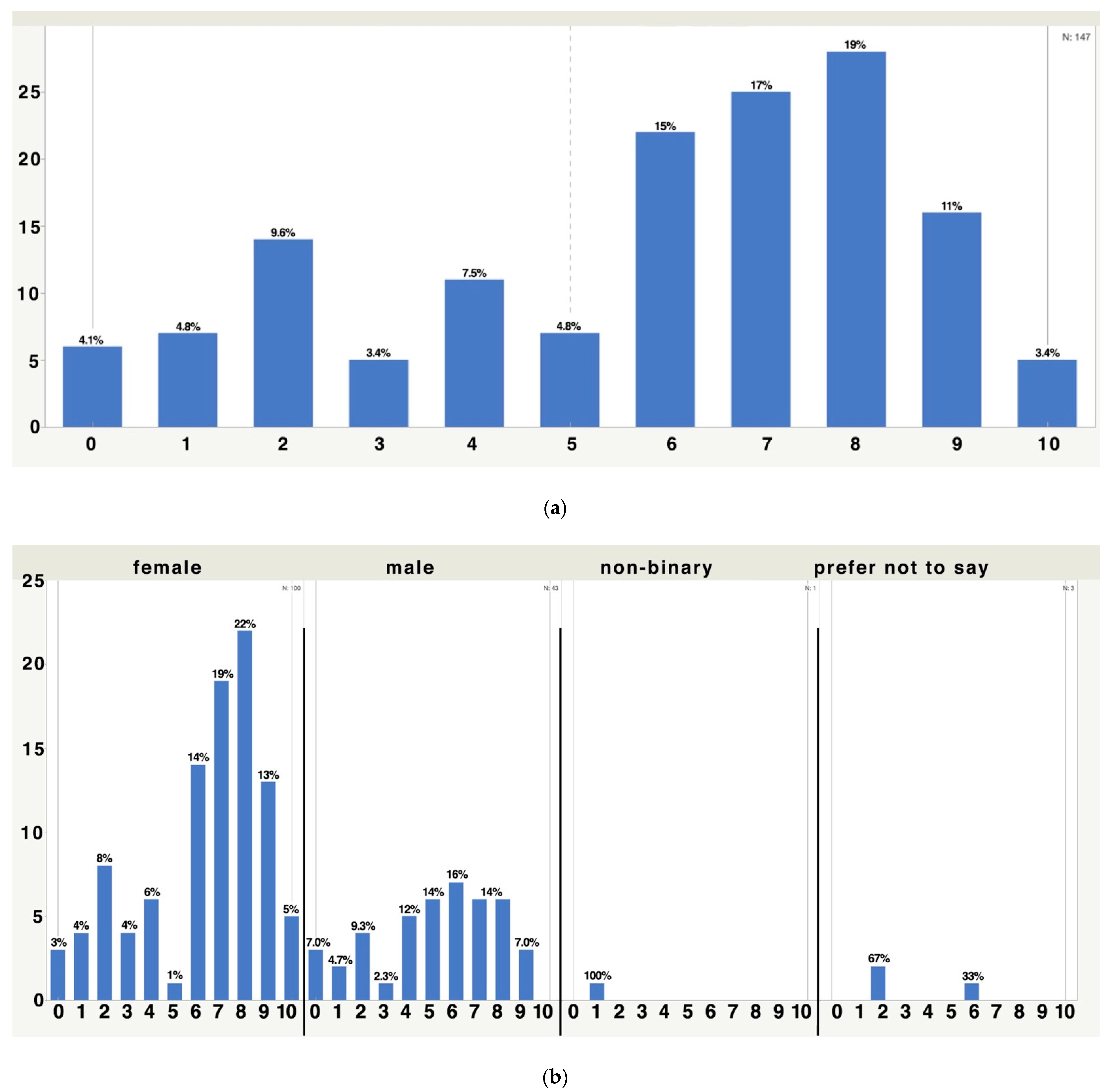

- How much has your way of socializing changed?Linear scale: 0 = it worsened; 5 = it did not change at all; 10 = it improved

- In what ways have the opportunities to meet other community members changed?Linear scale: 0 = really reduced the opportunities to meet; 5 = did not change at all; 10 = really increased the opportunities to meet

- How have open-air activities within the community changed?Linear scale: 0 = really reduced the open-air activities; 5 = did not change at all; 10 = really increased the open-air activities

- Did you suffer because of the (eventual) lack of social relations within the community?Linear scale: 0 = not suffered at all; 10 = I really suffered

- Did you suffer because of the (eventual) lack of social relations outside the community?Linear scale: 0 = not suffered at all; 10 = I really suffered

- In facing the emergency, do you think you have been luckier or not, compared with people living in traditional housing?Linear scale: 0 = less lucky; 5 = there is no difference; 10 = more luckySpatial considerations

- Do you think the way in which the community is using the COMMON spaces has changed?Linear scale: 0 = no; 10 = definitely yes

- Are you still using the shared space?Linear scale: 0 = no, we reduced the use of shared spaces a lot; 5 = there is no difference from before; 10 = yes, and even more than before

- Are you still using the open-air shared space?Linear scale: 0 = no, we reduced the use of open-air shared spaces a lot; 5 = there is no difference from before; 10 = yes, and even more than before

- Do you think living in co-housing has made it easier to face the contingency?Linear scale: 0 = no, living in co-housing made things harder; 5 = there is no difference; 10 = yes, living in co-housing made things easier

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Social Interaction: How Has Socialization Changed?

3.1.1. Ways of Socialization

3.1.2. Within and Outside a Co-Housing Community

3.2. The Use of Common/Shared Space

- -

- The first question was related to the respondent’s perception regarding the differences in the way of using the common spaces;

- -

- The second, third, and fourth questions gave us an idea of which shared spaces (mainly between indoor and outdoor) were the most used during the outbreak;

- -

- The last question explored how much the members of the community adapted any space, considering their new situation.

3.3. Sense of Gratitude for Living in Co-Housing

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Reference | Keywords | Main Topics | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||

| Amerio; Brambilla; Morganti; et al., 2020 | COVID-19; Lockdown; Housing Built Environment; Mental Health; Evidence-Based Design | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Babos; Szabó; Orbán & Benko, 2020 | Co-housing; Cohousing; Urban Housing; Collective Housing; Housing Classification; Housing Categorization; Participation; Field of Sharing; Social Sharing | x | x | ||||||

| Bettaieb; Alsabban, 2020 | Housing; Flexibility; Adaptability; COVID-19; Lifestyle | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Bigonnesse, 2012 | Aging In Place; Co-housing Community; Naturally Occurring Retirement Community; Neighborhood Environment; Constructivist Grounded Theory; Photovoice Interviews | x | x | x | |||||

| Boonstra, 2016 | Behavior; Co-housing; Mapping | x | x | ||||||

| Chakraborty & Maity, 2020 | COVID-19; Pandemics; Global Health; Economic; Prevention | x | |||||||

| D’Alessandro, Gola; Appolloni, Dettori; Fara; Rebecchi; Settimo; Capolongo, 2020 | COVID-19 Living Spaces; COVID-19 Housing; COVID-19 Built Environment; Public Health Recommendations; Healthy Living Spaces; Safe and Sustainable Housing; Sustainable Architecture; Indoor Air Quality; Water Consumption; Wastewater Management; Urban Solid Waste Management; Housing Automation | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Delendi, 2017 | Co-housing; Eco-Villages; Living Models; Sustainability | x | x | ||||||

| Giorgi, 2020 | Technocene; Co-housing; Sharing; Case-Study | x | x | x | |||||

| Glass, 2020 | Neighbors; Senior Co-housing; Living Arrangements; Aging Better Together | x | x | x | |||||

| Jacques-Aviñó, López-Jiménez; Medina-Perucha; et al., 2020 | Gender; Social Impact; Mental Health; COVID-19; Lockdown | x | x | x | |||||

| Jarvis, 2011 | Co-housing; Daily Life; Collective; Shared Space; Ethnography | x | x | x | |||||

| Lang, Carriou & Czischke, 2020 | Collaborative Housing; Literature Review; Conceptualization; Ontological Categorization; Collective Self-organized Housing | x | x | ||||||

| Le & Nguyen, 2020 | COVID-19; Psychological Consequences; Mental Health; Lockdowns; Stay-at-home Orders | x | x | x | |||||

| Pombo; Luz; Rodrigues; Ferreira; Cordovil, 2020 | COVID-19; Physical activity; Confinement routines; Working from Home; Children | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Power, Rogers, Kadi, 2020 | Public Housing; COVID-19; Literature Review | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Puplampu; Matthews; Puplampu; Gross; Pathak; Peters, 2019 | Aging; Aging in place; Co-housing; Mixed Methods; Older Adults; Quality of Life | x | x | x | |||||

| Rodgers, 2020 | Green Space; COVID-19; Planning Policy; Urban Commons | x | x | x | |||||

| Shin, 2004 | Co-housing; Life Satisfaction; Senior Co-housing; Quality of Life | x | x | x | |||||

| Tokazhanov; Tleuken; Guney; Turkyilmaz; Karaca, 2020 | COVID-19 Pandemic; Housing; Residential Buildings; SARS-CoV-2; Sustainability Requirements | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Wang; Pan & Hadjri, 2020 | Co-housing; Motivations; Housing Decisions; Social Sustainability; Environmental Sustainability | x | x | x | |||||

| Wang; Hadjri; Bennet; Morris, 2020 | Co-housing; Social Communication; Sustainable Living environments; low carbon lifestyle; affordable housing | x | x | x | |||||

| Boyraz & Legros, 2020 | Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Perceived Vulnerability to COVID-19; COVID-19-related Worries; Social Isolation Traumatic Stress | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Shim et al., 2020 | Coronavirus; COVID-19; Korea; Reproduction Number | x | x | ||||||

| Saez et al., 2020 | COVID-19 Mitigation; Physical Distancing; Generalized Linear Mixed Models R-INLA | x | x | ||||||

| Holmes et al., 2020 | COVID-19; Mental Health; Physical Health | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2010 | Loneliness; Regulatory Loop; Physiology; Health Behavior; Sleep; Intervention | x | x | ||||||

| Casagrande et al., 2020 | COVID-19; Generalized Anxiety Psychological Well-being; Post-traumatic Stress Disorder; PTSD; Sleep Quality | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Taylor et al., 2020 | Anxiety; Coronavirus; COVID-19; Fear; Pandemic; Stress; Xenophobia | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Park et al., 2020 | Coronavirus; COVID-19; Optimistic Bias; Perceived Risk; Risk Response; Health Information; Seeking Attention; Behavioral Outcomes | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Sanz-Barbero et al., 2018 | Heat Wave; Intimate Partner Violence; Femicides | x | x | ||||||

| Baiano et al., 2020 | Mental Health; Worry; Anxiety; Threat; Mindfulness; COVID-19 | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Iglesias-Sánchez, 2020 | Sentiment Analysis; Health Crisis; Isolation; Confinement; Emergency Response; Contagion of Emotions; COVID-19 | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Brooks et al., 2020 | Sentiment Analysis; Health Crisis; Isolation; Confinement; Emergency Response; Contagion of Emotions; COVID-19 | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Kirwan, 2017 | Insomnia; Anxiety; Emotion Regulation; Non-Acceptance; Strategies | x | x | ||||||

| Torales et al., 2020 | Outbreak; Coronavirus; Mental Health; COVID-19 | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Choi et al., 2020 | COVID-19; Depression; Anxiety; Mental Health; Hong Kong | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Zhang et al., 2020 | Nature; Positive Emotions; Judgment of Nature’s Beauty; Generosity | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Fry-Bowers, 2020 | x | x | x | x | |||||

| García de Avila, 2020 | Anxiety; Children; COVID-19; Pandemic; Social Isolation | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Fegert, 2020 | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Cao et al., 2020 | COVID-19; College Students; Psychological | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Somma et al., 2020 | COVID-19 Pandemic; Emotional Problems; Dysfunctional Personality Domains; COVID-19; Causal Beliefs | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Reynolds et al., 2008 | x | x | |||||||

| Liu, 2020 | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Lyu, 2012 | Public Health Crises; Traditional Media Dependency; Internet Dependency; Perception of Threat; Mainland China | x | x | ||||||

| Amerio et al., 2020 | COVID-19; Lockdown; Housing Built Environment; Mental Health; Evidence-based Design | x | x | x | |||||

| Heintzman, 2009 | Nature; Outdoor Recreation; Spirituality; Research; Theory | x | x | x | |||||

| Zhang et al., 2014 | Coronavirus; Mental Health; Sleep Quality; Physical Activity; Mitigation Strategies | x | x | x | |||||

| Chawla, 2015 | Health; Recreation and Open Space; Urban Design; Neighborhood Planning; Children; Adolescents | x | x | x | |||||

| Clayton et al., 2016 | Conservation; Biodiversity; Attitudes; Values; Social Context; Experience of Nature | x | x | x | |||||

| Ebrahimpour, 2020 | Biophilic Design; Hot and Dry Climate Biophilic Indicators; Meta-Synthesis Research; Nvivo Software | x | x | x | |||||

| Brambilla et al., 2019 | Built Environment; Evidence Based Design; Fall Reduction; Hospital; Job Satisfaction; Patient Satisfaction; Quality | x | x | x | |||||

| Amerio et al., 2020 | COVID-19; Lockdown; Housing Built Environment; Mental Health; Evidence-Based Design | x | x | x | x | x | |||

Appendix B

| Female | Male | NB * | PNTS | TOTAL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 43 | 1 (%) | 3 | 147 | |

| 8-How much has your way of socializing changed? | 3.24 (2.04) | 4.09 (2.31) | 3.00 | 5.67 (2.31) | 3.54 (2.16) |

| 9-How much has the way to meet other community members changed? | 3.18 (1.98) | 3.69 (2.27) | 3.00 | 2.33 (0.58) | 3.31 (2.05) |

| 10-How much have the open-air activities within the community changed? | 5.92 (2.86) | 5.63 (2.20) | 4.00 | 5.67 (1.15) | 5.82 (2.64) |

| 11-Have you suffered because of the (eventual) lack of social relations within the community? | 4.93 (2.79) | 3.83 (2.76) | 1.00 | 2.33 (1.15) | 4.53 (2.81) |

| 12-Have you suffered because of the (eventual) lack of social relations outside the community? | 6.27 (2.66) | 5.16 (2.60) | 1.00 | 3.33 (2.31) | 5.85 (2.71) |

| 13-Facing the emergency, do you think you have been luckier or not, compared with people living in traditional housing? | 9.01 (1.80) | 7.72 (2.23) | 8.00 | 9.33 (0.58) | 8.63 (2.00) |

| 14-Do you think the way in which the community is using the COMMON spaces has changed? | 9.24 (2.10) | 8.58 (2.30) | 9.00 | 10.00 (0.00) | 9.06 (2.15) |

| 15-Are you still using the shared space? | 2.13 (2.47) | 3.00 (2.92) | 1.00 | 0.67 (1.15) | 2.35 (2.61) |

| 16-Are you still using the open-air shared space? | 6.98 (3.03) | 6.81 (2.75) | 4.00 | 8.00 (1.73) | 6.93 (2.92) |

| 17-Do you think living in co-housing has made it easier to face the contingency? | 8.57 (2.19) | 7.77 (2.11) | 6.00 | 9.33 (0.58) | 8.33 (2.17) |

| 18–30 | 31–40 | 41–50 | 51–60 | 61–70 | 70+ | PNTS | TOTAL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 6 | 14 | 27 | 56 | 41 (%) | 1 | 147 | |

| 8-How much has your way of socializing changed? | 3.00 (1.41) | 4.33 (2.58) | 3.00 (2.42) | 3.85 (2.14) | 3.61 (2.28) | 3.34 (1.96) | 5.00 | 3.54 (2.16) |

| 9-How much has the way to meet other community members changed? | 2.00 (1.41) | 5.50 (3.62) | 2.43 (1.09) | 3.33 (1.86) | 3.55 (2.27) | 3.02 (1.65) | 3.00 | 3.31 (2.05) |

| 10-How much has the open-air activities within the community changed? | 2.00 (1.41) | 7.17 (1.83) | 5.50 (3.32) | 6.52 (2.19) | 5.73 (2.75) | 5.54 (2.53) | 7.00 | 5.82 (2.64) |

| 11-Did you suffer because of the (eventual) lack of social relations within the community? | 6.00 (1.41) | 4.00 (3.03) | 5.36 (2.84) | 4.15 (3.00) | 4.18 (2.94) | 5.07 (2.45) | 1.00 | 4.53 (2.81) |

| 12-Did you suffer because of the (eventual) lack of social relations outside the community? | 7.00 (2.83) | 6.67 (2.73) | 6.57 (2.17) | 5.26 (3.17) | 5.27 (2.70) | 6.63 (2.45) | 6.00 | 5.85 (2.71) |

| 13-Facing the emergency, do you think you have been luckier or not, compared with people living in traditional housing? | 6.00 (4.24) | 8.83 (1.17) | 7.86 (2.54) | 9.19 (1.39) | 8.68 (2.00) | 8.54 (2.06) | 10.00 | 8.63 (2.00) |

| 14-Do you think the way in which the community is using the COMMON spaces has changed? | 10.00 (0.00) | 10.00 (0.00) | 9.50 (1.34) | 8.81 (2.56) | 9.27 (1.65) | 8.61 (2.75) | 10.00 | 9.06 (2.15) |

| 15-Are you still using the shared space? | 0.50 (0.71) | 2.40 (1.14) | (1.43) 2.62 | 3.30 (3.18) | 2.41 (2.59) | 2.05 (2.32) | 2.00 | 2.35 (2.61) |

| 16-Are you still using the open-air shared space? | 3.50 (4.95) | 7.40 (2.88) | 6.14 (4.00) | 7.26 (2.64) | 7.00 (2.87) | 6.93 (2.71) | 10.00 | 6.93 (2.92) |

| 17-Do you think living in co-housing has made it easier to face the contingency? | 5.50 (4.95) | 7.67 (2.07) | 6.64 (3.67) | 8.56 (1.55) | 8.54 (2.15) | 8.68 (1.44) | 10.00 | 8.33 (2.17) |

References

- Abebaw Mengistu, Y. COPD patients in a COVID-19 society: Depression and anxiety. Expert Rev. Respir. Med. 2020, 15, 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Franch-Pardo, I.; Napoletano, V.; Rosete-Verges, F.; Billa, L. Spatial analysis and GIS in the study of COVID-19. A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 739, 140033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrot, J.; Grassi, B.; Sauvagnat, J. Costs and Benefits of Closing Businesses in a Pandemic. SSRN 2020, 1–50. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3599482, (accessed on 24 February 2021).

- Gumel, A.B.; Iboi, E.A.; Ngonghala, C.N.; Elbasha, E.H. A primer on using mathematics to understand COVID-19 dynamics: Modeling, analysis and simulations. Infect. Dis. Model. 2021, 6, 148–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Jaspreet and Singh, Jagandeep, COVID-19 and Its Impact on Society. Electron. Res. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2020, 2. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3567837 (accessed on 3 April 2020).

- Holmes, E.A.; O’Connor, R.C.; Perry, V.H.; Tracey, I.; Wessely, S.; Arseneault, L.; Ballard, C.; Christensen, H.; Silver, R.C.; Everall, I.; et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiano, C.; Zappullo, I.; Conson, M. Tendency to Worry and Fear of Mental Health during Italy’s COVID-19 Lockdown. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serafini, G.; Parmigiani, B.; Amerio, A.; Aguglia, A.; Sher, L.; Amore, M. The psychological impact of COVID-19 on the mental health in the general population. QJM 2020, 113, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torales, J.; O’Higgins, M.; Castaldelli-Maia, J.M.; Ventriglio, A. The outbreak of COVID-19 coronavirus and its impact on global mental health. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2020, 66, 317–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Allam, Z.; Jones, D.S. On the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Outbreak and the Smart City Network: Universal Data Sharing Standards Coupled with Artificial Intelligence (AI) to Benefit Urban Health Monitoring and Management. Healthcare 2020, 8, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- EQUIDE. La Ibero Presenta la Encuesta de Seguimiento de los Efectos del Covid en el Bienestar de los Hogares Mexicanos #Encovid. Available online: https://ibero.mx/sites/default/files/comunicado_encovid-19_completo.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2021).

- Ziccardi, A. Las grandes regiones urbanas y el distanciamiento social impuesto por el COVID-19. Astrolabio 2020, 25, 46–64. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, C.; Chen, J.; Zhou, Y.; Hua, L.; Yuan, J.; He, S.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, S.; Jia, Q.; Zhao, C.; et al. The effectiveness of the quarantine of Wuhan city against the Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Well-mixed SEIR model analysis. J. Med. Virol. 2019, 92, 841–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ferguson, N.M.; Laydon, D.; Nedjati-Gilani, G.; Imai, N.; Ainslie, K.; Baguelin, M.; Bhatia, S.; Boonyasiri, A.; Cucunubá, Z.; Cuomo-Dannenburg, G.; et al. Impact of Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions (NPIs) to Reduce COVID-19 Mortality and Healthcare Demand; Imperial College London: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyraz, G.; Legros, D.N. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and traumatic stress: Probable risk factors and correlates of posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Loss Trauma 2020, 25, 503–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, E.; Tariq, A.; Choi, W.; Lee, Y.; Chowell, G. Transmission potential and severity of COVID-19 in South Korea. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 93, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saez, M.; Tobias, A.; Varga, D.; Barcelo, M.A. Effectiveness of the measures to flatten the epidemic curve of COVID-19. The case of Spain. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 727, 138761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Supporting the Continuation of Teaching and Learning during the COVID-19 Pandemic Annotated Resources for Online Learning; OECD: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Greenstone, M.; Nigam, V. Does Social Distancing Matter? Working Paper No. 2020-26; University of Chicago, Becker Friedman Institute for Economics: Chicago, IL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Ou, J.; Luo, S.; Wang, Z.; Chang, E.; Novak, C.; Shen, J.; Zheng, S.; Wang, Y. Perceived Social Support Protects Lonely People Against COVID-19 Anxiety: A Three-Wave Longitudinal Study in China. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 566965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkley, L.C.; Cacioppo, J.T. Loneliness matters: A theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Ann. Behav. Med. A Publ. Soc. Behav. Med. 2010, 40, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Casagrande, M.; Favieri, F.; Tambelli, R.; Forte, G. The enemy who sealed the world: Effects quarantine due to the COVID-19 on sleep quality, anxiety, and psychological distress in the Italian population. Sleep Med. 2020, 75, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Landry, C.A.; Paluszek, M.M.; Fergus, T.A.; McKay, D.; Asmundson, G.J.G. Development and initial validation of the COVID stress scales. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 72, 102232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Landry, C.A.; Paluszek, M.M.; Fergus, T.A.; McKay, D.; Asmundson, G.J.G. COVID stress syndrome: Concept, structure, and correlates. Depress. Anxiety 2020, 37, 706–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Sun, Z.; Wu, L.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, F.; Shang, Z.; Jia, Y.; Gu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Prevalence and risk factors of acute posttraumatic stress symptoms during the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, China. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 283, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, T.; Ju, I.; Ohs, J.E.; Hinsley, A. Optimistic bias and preventive behavioral engagement in the context of COVID-19. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2020, 17, 1859–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, S.L.; Maner, J.K. Overperceiving disease cues: The basic cognition of the behavioral immune system. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 102, 1198–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ozer, E.J.; Best, S.R.; Lipsey, T.L.; Weiss, D.S. Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and symptoms in adults: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 52–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolin, D.F.; Foa, E.B. Sex differences in trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder: A quantitative review of 25 years of research. Psychol. Bull. 2006, 132, 959–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewin, C.R.; Andrews, B.; Valentine, J.D. Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2000, 68, 748–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagers, S. Domestic Violence Growing in the Wake of Coronavirus Outbreak. The Conversation. Available online: https://theconversation.com/domestic-violence-growing-in-wake-of-coronavirus-outbreak-135598 (accessed on 11 April 2020).

- Taub, A. A New COVID-19 Crisis: Domestic Abuse Rises Worldwide. New York Times. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/06/world/coronavirus-domestic-violence.html (accessed on 13 April 2020).

- Sanz-Barbero, B.; Linares, C.; Vives-Cases, C.; González, J.L.; López-Ossorio, J.J.; Díaz, J. Heat wave and the risk of intimate partner violence. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 644, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Na, K.; Garrett, R.K.; Slater, M.D. Rumor Acceptance during Public Health Crises: Testing the Emotional Congruence Hypothesis. J. Health Commun. 2018, 23, 791–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Sánchez, P.P.; Vaccaro Witt, G.F.; Cabrera, F.E.; Jambrino-Maldonado, C. The Contagion of Sentiments during the COVID-19 Pandemic Crisis: The Case of Isolation in Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirwan, M.; Pickett, S.M.; Jarrett, N.L. Emotion regulation as a moderator between anxiety symptoms and insomnia symptom severity. Psychiatry Res. 2017, 254, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, E.P.H.; Hui, B.P.H.; Wan, E.Y.F. Depression and anxiety in Hong Kong during COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ma, X.; Di, Q. Mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemics and the mitigation e_ects of exercise: A longitudinal study of college students in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashidi Fakari, F.; Simbar, M. Coronavirus Pandemic and Worries during Pregnancy; a Letter to Editor. Arch. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2020, 8, e21. [Google Scholar]

- Evenson, K.R.; Savitz, D.A.; Huston, S.L. Leisure-time physical activity among pregnant women in the US. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2004, 18, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fry-Bowers, E.K. Children are at risk from COVID-19. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2020, 53, A10–A12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Garcia Avila, M.A.; Hamamoto Filho, P.T.; Jacob, F.L.; Alcantara, L.R.; Berghammer, M.; Jenholt Nolbris, M.; Olaya-Contreras, P.; Nilsson, S. Children’s Anxiety and Factors Related to the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Exploratory Study Using the Children’s Anxiety Questionnaire and the Numerical Rating Scale. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fegert, J.M.; Vitiello, B.; Plener, P.L.; Clemens, V. Challenges and burden of the coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for child and adolescent mental health: A narrative review to highlight clinical and research needs in the acute phase and the long return to normality. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2020, 14, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Fang, Z.; Hou, G.; Han, M.; Xu, X.; Dong, J.; Zheng, J. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 287, 112934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somma, A.; Gialdi, G.; Krueger, R.F.; Markon, K.E.; Frau, C.; Lovallo, S.; Fossati, A. Dysfunctional personality features, non-scientifically supported causal beliefs, and emotional problems during the first month of the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2020, 165, 110139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, D.; Garay, J.; Deamond, S.; Moran, M.; Gold, W.; Styra, R. Understanding, compliance and psychological impact of the SARS quarantine experience. Epidemiol. Infect. 2008, 136, 997–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.J.; Bao, Y.; Huang, X.; Shi, J.; Lu, L. Mental health considerations for children quarantined because of COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 347–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gruzd, A.; Doiron, S.; Mai, P. Is Happiness Contagious Online? A Case of Twitter and the 2010 Winter Olympics. In Proceedings of the 2011 44th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Kauai, HI, USA, 4–7 January 2011; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, J.C. How young Chinese depend on the media during public health crises? A comparative perspective. Public Relat. Rev. 2012, 38, 799–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, W. The Last Global Crisis Didn’t Change the World. But This One Could. The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com (accessed on 24 March 2020).

- Rogers, D.; Power, E. Housing policy and the COVID-19 pandemic: The importance of housing research during this health emergency. Int. J. Hous. Policy 2020, 20, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetta, G.; Moroni, S. La Città Intraprendente, Comunità Contrattuali e Sussidiarietà Orizzontale; Carocci Editore: Rome, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Guidotti, F. Ecovillaggi e Cohousing. Dove Sono, Chi li Anima, Come Farne Parte o Realizzarne di Nuovi; Terra Nuova Edizioni: Cesena, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi, E. The Co-Housing Phenomenon. Environmental Alliance in Times of Changes; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sfriso, S. Dire, fare … coabitare. In L’abitare Condiviso: Le Residenze Collettive Dalle Origini al Cohousing; Narne, E., Sfriso, S., Eds.; Marsilio: Venezia, Italy, 2013; pp. 43–59. [Google Scholar]

- McCamant, K.; Durrett, C. Cohousing: A Contemporary Approach to Housing Ourselves; Ten Speed Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lietaert, M. Il cohousing: Origini, storia ed evoluzione in Europa e nel mondo. In Famiglie, Reti Famigliari e Cohousing; Sapio, A., Ed.; Franco Angeli Editore: Milano, Italy, 2010; pp. 140–148. [Google Scholar]

- Vestbro, D.U.; Horelli, L. Design for gender equality—The history of cohousing ideas and realities. Built Environ. 2012, 38, 315–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Muxí, Z. Mujeres, Casas y Ciudades: Más Allá del Umbral; DPR: Barcelona, Spain, 2018; p. 61. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Simons, R.F.; Losito, B.D.; Fiorito, E.; Miles, M.A.; Zelson, M. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1991, 11, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amerio, A.; Brambilla, A.; Morganti, A.; Aguglia, A.; Bianchi, D.; Santi, F.; Costantini, L.; Odone, A.; Costanza, A.; Signorelli, C.; et al. COVID-19 Lockdown: Housing Built Environment’s Effects on Mental Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, M.P.; Alcock, I.; Grellier, J.; Wheeler, B.W.; Hartig, T.; Warber, S.L.; Bone, A.; Depledge, M.H.; Fleming, L.E. Spending at least 120 minutes a week in nature is associated with good health and wellbeing. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Corraliza, J.A.; Berenguer, J.; Martín, R. Medio Ambiente, Bienestar Humano y Responsabilidad Ecológica; Editorial Resma: Madrid, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Heintzman, P. Nature-Based Recreation and Spirituality: A Complex Relationship. Leis. Sci. 2009, 32, 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.W.; Piff, P.K.; Iyer, R.; Koleva, S.; Keltner, D. An occasion for unselfing: Beautiful nature leads to prosociality. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 37, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, L. Benefits of Nature Contact for Children. J. Plan. Lit. 2015, 30, 433–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S.; Colleony, A.; Conversy, P.; Maclouf, E.; Martin, L.; Torres, A.C.; Truong, M.X.; Prevot, A.C. Transformation of experience: Toward a new relationship with nature. Conserv. Lett. 2016, 10, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johnson, N. Why Biophilic Architecture Works: Five Reasons and Case Studies. Available online: https://www.architectureanddesign.com.au/features/features-articles/why-biophilic-architecture-works-five-reasons-and (accessed on 30 September 2014).

- Ebrahimpour, M. Proposing a framework of biophilic design principles in hot and arid climate of Iran by using grounded theory. CEE 2020, 16, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega Andeane, P.; Estrada, C.; Toledano, F.; Campos, J. Calidad ambiental, carga y estrés en cuidadores primarios informales de un hospital pediátrico. In Ambientes Hospitalarios y Estrés; Ortega, P., Estrada, C., Eds.; Facultad de Psicología UNAM: Mexico City, Mexico, 2018; pp. 65–96. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Zimring, C.; Zhu, X.; DuBose, J.; Seo, H.B.; Choi, Y.S.; Quan, X.; Joseph, A.A. Review of the research literature on evidence-based healthcare design. Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2008, 1, 61–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brambilla, A.; Rebecchi, A.; Capolongo, S. Evidence based hospital design. A literature review of the recent publications about the EBD impact of built environment on hospital occupants’ and organizational outcomes. Ann. Ig. 2019, 31, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Garber, M. Homes Actually Need to Be Practical Now: One of the Ironies of Social Distancing Is That It Can Put Privacy in Short Supply. The Atlantic. Available online: https://www.theatlantic.com/culture/archive/2020/03/finding-privacy-during-pandemic/608944/ (accessed on 11 April 2020).

- Rubin, G.J.; Wessely, S. The psychological effects of quarantining a city. BMJ 2020, 368, m313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stokols, D. The changing morphology of indoor ecosystems in the twenty-first century driven by technological, climatic, and sociodemographic forces. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 2018, 24, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisanti, A.S.; Duran, D.; Greene, R.N.; Reno, J.; Luna-Anderson, C.; Altschul, D.B. A longitudinal analysis of peer-delivered permanent supportive housing: Impact of housing on mental and overall health in an ethnically diverse population. Psychol. Serv. 2017, 14, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, K.; Erqou, S.; Shah, N.; Nazir, U.; Morrison, A.; Choudhary, G.; Wu, W. Association of poor housing conditions with COVID-19 incidence and mortality across US counties. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0241327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNSD. Informe Sobre los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible 2019. División de Estadística de las Naciones Unidas. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2019/ (accessed on 13 April 2020).

- Azzopardi-Muscat, N.; Brambilla, A.; Caracci, F.; Capolongo, S. Synergies in design and health. The role of architects and urban health planners in tackling key contemporary public health challenges. Acta Biomed. 2020, 91, 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Signorelli, C.; Capolongo, S.; D’Alessandro, D.; Fara, G.M. The homes in the COVID-19 era. How their use and values are changing. Acta Biomed 2020, 91 (Suppl. 9), 92–94. [Google Scholar]

- Groat, L.N.; Wang, D. Architectural Research Methods, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 280–292. [Google Scholar]

- Mertens, D. Research Methods in Education and Psychology; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998; pp. 115–117. [Google Scholar]

- Cohousing. Available online: https://www.cohousing.org/directory/ (accessed on 15 April 2020).

- Smith, W.G. Does Gender Influence Online Survey Participation? A Rec-ord-Linkage Analysis of University Faculty Online Survey Response Behavior. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED501717 (accessed on 9 March 2021).

- Underwood, D.; Kim, H.; Matier, M. To mail or to Web: Comparisons of survey response rates and respondent characteristics. In Proceedings of the 40th Annual Forum of the Association for Institutional Research, Cincinnati, OH, USA, 21–24 May 2000. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Giorgi, E.; Martín López, L.; Garnica-Monroy, R.; Krstikj, A.; Cobreros, C.; Montoya, M.A. Co-Housing Response to Social Isolation of COVID-19 Outbreak, with a Focus on Gender Implications. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7203. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137203

Giorgi E, Martín López L, Garnica-Monroy R, Krstikj A, Cobreros C, Montoya MA. Co-Housing Response to Social Isolation of COVID-19 Outbreak, with a Focus on Gender Implications. Sustainability. 2021; 13(13):7203. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137203

Chicago/Turabian StyleGiorgi, Emanuele, Lucía Martín López, Ruben Garnica-Monroy, Aleksandra Krstikj, Carlos Cobreros, and Miguel A. Montoya. 2021. "Co-Housing Response to Social Isolation of COVID-19 Outbreak, with a Focus on Gender Implications" Sustainability 13, no. 13: 7203. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137203

APA StyleGiorgi, E., Martín López, L., Garnica-Monroy, R., Krstikj, A., Cobreros, C., & Montoya, M. A. (2021). Co-Housing Response to Social Isolation of COVID-19 Outbreak, with a Focus on Gender Implications. Sustainability, 13(13), 7203. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137203