1. Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), dementia is one of the more serious challenges of the future [

1]. Most countries have a variety of policies, institutions and financial aids implemented to ease the burden on families carrying out the bulk of care work for their relatives with dementia. However, due to the COVID-19 outbreak, some of these support systems have become much more difficult (or even impossible) to access or utilize, an effect mediated by the mandatory stringency measures adopted by governments during the first wave of the pandemic to mitigate its impact on the population.

The authors have chosen two countries—Italy and Hungary—to examine the changes in availability and utilization of care-related help since the outbreak for four reasons: (1) they had distinctively different social support systems in place for families caring for people affected by dementia, even before the pandemic; (2) they were different in terms of the severity of the pandemic’s impact (Italy was one of the countries hit hardest by the outbreak in Europe, whereas Hungary was less severely affected); (3) the divergence of the containment measures imposed by the two governments; and (4) being characterized by a different degree of resilience concerning the changes experienced in the supply of both formal and informal care to older adults in need of assistance during the first outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Concerning the latter aspect, a forthcoming study [

2] based on recently released data from the Survey of Health, Aging and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) COVID-19 period, identified different clusters of European countries (not in line with the traditional classification of welfare regimes [

3]) characterized by a mix of changes in the provision of informal care and formal care compared to the pre-pandemic crisis. Both Italy and Hungary belong to clusters of countries showing challenges concerning the degree of resilience. However, Italy is part of a cluster having weak resilience in informal care and moderate resilience in formal care provision, while Hungary belongs to a cluster with weak resilience in both formal and informal care (i.e., with a higher share of older adults reporting difficulties in receiving formal care—i.e., home care—and a quite low share receiving informal care from people outside their home, being the supply of both types of care provision dramatically decreased compared to the pre-pandemic period) [

2]. These findings substantially echo another study [

4] using SHARE data, showing that after the first wave of the pandemic, Hungary was characterized by lower percentages of older adults receiving/providing informal care from/to others outside their own household compared to Italy.

Due to this overall different degree of “care resilience” experienced during the first wave of the pandemic in Hungary and Italy, comparing these two countries could be useful to evaluate the impact on family caregivers of older people with dementia, in order to identify key priorities concerning measures to put in place for supporting this group of caregivers at national level. This would also provide useful insights contributing to the ongoing international debate on how to best develop care policies for supporting both older people with dementia and their caregivers in (post)pandemic times.

To this purpose, an online survey for in-home family carers of older people living with dementia was designed with the aim of finding answers to the following research questions:

- (1)

What care responsibilities did family carers have before the COVID-19 outbreak?

- (2)

What types and sources of care-related help did families utilize before the pandemic, and how did the pandemic and the related government measures change this?

- (3)

What other care-related changes did families experience in relation to the pandemic?

Factors possibly contributing to change, as well as cross-country differences, were also examined.

1.1. Family Carers of Older People Living with Dementia

At present, around 50 million people live with dementia worldwide, and there are nearly 10 million new cases every year. The total number of people with this disorder is projected to reach 82 million in 2030, and 152 million in 2050. The estimated proportion of the population aged 60 and over with dementia at any given time is between 5–8 per cent [

5]. Dementia ranges from mild (early stage) to severe (late stage), with the probability of a more severe stage increasing substantially with age, each stage requiring different types of care and services, according to their mental health needs [

6,

7].

Many studies highlighted that dementia care systems rely on work carried out by family carers [

6,

7], since a significant proportion of older people with dementia live at home, and are informally cared for (mostly by the women in their families) [

8].

Dementia can be a great burden on families tasked with care responsibilities, often causing physical and emotional stress and financial problems [

1]. Caregivers of people with dementia are more burdened than the caregivers of people with other diseases [

9,

10], and often experience high levels of anxiety, depression, stress, morbidity, physical problems and low quality of life [

11,

12]. In Italy, the burden of dementia caregivers appears to be especially heavy, with an average of 4.4 h of direct assistance and 10.8 h of supervision needed per day. This commitment has consequences on the caregivers’ personal and social life, and on their ability to work (the number of unemployed caregivers tripled since 2006, with those still working reporting repeated absences and, especially in the case of women, only being able to work part-time). Balancing care and paid work is also a difficulty family caregivers face [

13,

14]. Negative effects on health include feeling tired, lack of rest, and showing symptoms of depression [

15,

16], resulting in family caregivers being considered as the “hidden secondary patients” [

17].

1.2. Changes Brought on by the COVID-19 Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected the lives of people throughout the world. One of the population groups most affected by the still ongoing pandemic was that of frail older people [

18], particularly those in very old age segments, among whom incidence rates of dementia are high [

19]. Family carers were hit by the sudden removal of social support services, and this increased their burden substantially; they also reported concerns about when services would re-open [

20]. A number of research papers focused on the diminishing sources of support in the first wave of the pandemic, and the challenges faced by carers. In the United Kingdom (UK), Barry and Hughes [

21] appealed for support for family carers and healthcare professionals treating older people with dementia, as they have a critical role in the management of medicine intake. In Austria, due to a reduction in available therapies and support (e.g., rehabilitative) services for older people in need of care, symptoms of people cared for (including those with dementia) worsened, leading to an increased burden for family carers [

22]. Vaitheswaran et al. [

23] carried out a qualitative telephone survey in India with 31 caregivers of people living with dementia. Some respondents reported a need for immediate and others for long-term support during the pandemic, and they suggested methods to meet their needs, such as the use of video consultations, telephone-based support, clinic-based in-person visits and post-pandemic services. Lack of outpatient rehabilitation services and increased stress for family caregivers was found in Argentina [

24]. Tsapanou et al. [

25] reported that due to the limitation of available support sources, caregivers in Greece experienced a great increase in their psychological and physical burden. Simultaneous work commitments and growing care responsibilities were also challenging for Irish family members during the pandemic [

26]. Other studies on COVID-19 seem to confirm a deterioration in well-being as a result of an increased burden as carers step in to fill in care gaps [

27,

28].

Another research focus was the change in the role of the caregiver paid by the family, e.g., in Argentina [

24]. Many families decided to discontinue paid carers entering the home due to the risk of infection, resulting in unpaid carers having to put in the care hours to support the person living with dementia [

29]. According to the Alzheimer Society of Ireland, 77 per cent of family carers of people with dementia experienced an increase in the level of care they provide as they were forced to step in instead of the usually available care support. The fear of spreading the disease while assisting patients with instrumental activities was a major concern [

30].

Even research that did not originally focus on family carers of older people with dementia unearthed some new information on the topic. In Hungary, Tróbert et al. [

31] carried out an online survey among family carers of older people. They found that the burden of those caring for someone with dementia in their home increased significantly during lockdown, compared to those whose care recipient was unaffected by the disease.

Apart from its devastating effects, the pandemic also brought on a few positive changes in the care work carried out by families. In Spain, Goodman-Casanova et al. [

32] found that telehealth could support adults with mild cognitive impairment/dementia living at home. Cuffaro et al. [

33] pointed out that in Italy the pandemic is speeding up the use of telemedicine and digital technology in the care of people with dementia. Home-based care for people with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias was the focus of Sm-Rahman et al. [

34], who overviewed challenges specific to this group and their carers, and proposed solutions to these challenges on the structural and personal level. During the first months of the pandemic, remote interventions were also developed and refined in Italy [

35], which helped identify risk situations, monitor the condition of people with dementia, provide support to caregivers, and ensure communication between patients, caregivers and health and social workers involved in the care network. The pandemic therefore contributed to the adoption of reliable and sustainable remote interventions, which could be an opportunity in the future to improve and simplify the process of taking charge and promoting continuity of care. In Hungary, the implementation of the e-receipt system made it easier to get prescriptions for necessary medication over the phone, which reduced doctor-patient encounters for examinations and medical interventions.

1.3. Dementia-Related Health and Social Services Supporting Older People with Dementia Living at Home

1.3.1. Italy

Around 1.3 million people were estimated to have dementia in Italy in 2018, representing 2.1% of the population, and 9% of those aged 65 or over [

36]; about 80% are assisted directly by a family member [

15].

With regard to support services, home healthcare in Italy (Assistenza Domiciliare Integrata or ADI) is funded by the National Health Service, and includes health services at home (home nursing, physiotherapy, specialist and doctors’ visits) to limit functional decline and to improve the quality of life of the person with dementia within the family environment, avoiding, as far as possible, hospitalization or care in a residential facility. Only 9.5 per cent of older people with dementia receive assistance via home healthcare [

15]. The number of hours of care per recipient per year is 20 on average, showing the limitations of this public service [

37]. Home care (Servizio di Assistenza Domiciliare, SAD) is provided and funded by the municipality, and consists of personal hygiene care and meals on wheels provided to non-self-sufficient older persons. Users partly pay for the service on an income basis and can receive a voucher from local authorities to be used for covering service costs.

SAD is considered inadequate to cover the daily needs of both people with dementia and their caregivers. Interventions represent a drop in the ocean since, regardless of need, solutions offered are always the same (services carried out during the day), while the overall management of the situation rests with the family or remains precarious [

38]. Moreover, the service is extremely variable across Italian regions. The integration between home healthcare (ADI) and home care (SAD) is envisaged by regulation, but it has never been defined nationally, remaining a regional responsibility according to the division of competences between the national and regional level (i.e., health and social services planning and organisation is regulated on a regional level). Therefore, healthcare and social services (e.g., ADI and SAD), as well as social and health facilities for people with dementia like day care centres, are differently supplied among Italian areas (e.g., mostly in the North), and are only managed on an integrated basis in some regions [

39]. The Italian long-term care (LTC) system also includes a care allowance element (indennità di accompagnamento), which amounted to EUR 520.29 per month in 2020. This cash-for-care benefit is intended to support the choice of keeping non-self-sufficient older persons at home, in their usual social and emotional environment—in line with the Italian “familistic” culture—as an alternative to permanent placement in a protected residence. The benefit mainly aims to co-fund the payment of private home helpers. Approximately 38 per cent of Italian families caring for their relatives with dementia are able to employ non-professional carers, mainly migrant care workers [

15]. Migrant care workers are particularly relevant to older people with higher care needs, e.g., people with dementia, albeit their employers usually come from higher socio-economic backgrounds [

40,

41]. Cash-for-care allowances have resulted in families outsourcing care services to migrant paid carers [

41]. However, only about one-third of those who have the help of a migrant paid carer receive public contributions, most of them in the form of a care allowance. The other two-thirds cover the cost of private assistance from the family budget. Due to this huge expense averaging EUR 800 per month, the majority of family carers (56%) reported having to make changes to make ends meet: 48% reduced consumption in order to keep the employee, 20% had to dip into their savings, and 3% of households even had to go into debt [

15].

The official number of migrant care workers (the so-called “badanti”) stood at 407,000 in 2019 [

42], which is only a fraction of the actual figures as this sector is heavily characterized by informal/undeclared work in Italy. This means that the sheer number of migrant care workers alone makes them an important stakeholder in dementia care in Italy. However, countries utilizing migrant healthcare workers tend not to even recognize the contribution and importance of skilled migrant healthcare workers at policy level [

43], and “badanti” in Italy similarly remain largely absent in policy debates.

The dementia care voucher is another element of integrated health and social care and is provided by local health and social services. The purpose of the voucher is to help families adequately manage needs at the early stage of dementia, allowing for the acquisition of a psycho-educational intervention for the caregiver and family members. This benefit is not dispensed evenly throughout the country. Services supporting the family are the Alzheimer Day centres, consisting in semi-residential care facilities offering respite to the family, and providing cognitive stimulation to older persons living with dementia. Although these centres represent an essential level of assistance that each region must guarantee to older adults with dementia [

44], in reality they are only available to 12.5% of families [

15].

The Italian care model, based on a low supply of services and a high diffusion of the care allowance (used mostly as a contribution to the cost of paid family assistants, mainly “badanti”), places most of the responsibility on families to organize assistance for their relatives with dementia, acting, in most cases, as their own “case manager”. This setup requires direct commitment from families to care for their frail older members, as well as a significant economic effort. Family carers who are employed in Italy can request three days of paid leave per month, and two years unpaid leave. However, working carers find it difficult to combine paid work and caring responsibilities in many cases, since companies (especially small and medium enterprises) do not always provide work-life balance measures, such as flexible working time arrangements.

1.3.2. Hungary

Between 146,000 [

36] and 250,000 [

45] people were estimated to have dementia in Hungary in 2018, representing 1.5% of the population and 7.4% of those aged 65 or over (Alzheimer Europe 2019). The total number of family carers is estimated to be between 400,000–500,000 [

45].

Social care in Hungary is regulated by the Social Welfare Act of 1993 [

46], which divides services into basic and specialist care. All local governments have the mandatory task of providing home help to older people. This includes the following categories: home help/care (maximum four hours a day) such as cleaning, shopping, administration, medicine administration, delivering food, and conversation; alarm system-based home help (a device to be used for emergency calls to social services); meals on wheels (one hot meal a day); and access to services in villages with less than 600 inhabitants, and parts of the country where houses (mostly farms) are isolated from nearby settlements. Local governments covering over 3000 inhabitants are also obliged to provide a specialist service (day care centre for older people) [

47]. Day care centres specifically for dementia patients are not very common, although their numbers are increasing.

Residential settings, nursing homes and respite care services are not part of the basic social care system for older people, and their number is low. These institutions are either private, public, or belong to churches or non-governmental organizations.

Apart from various types of pensions and benefits, the only financial aid available to family carers is the nursing fee. This social benefit amounted to around EUR 81.42 per month in 2020 (11.5% of the average monthly wage) and is insufficient to be of any meaningful help towards increased living expenses. The nursing fee’s main target group is not family carers of older people, but those caring for disabled children.

Some services (especially home nursing) are available through the healthcare system, which is regulated by the Healthcare Act of 1997 [

48]. Generally, the healthcare and social care systems are not harmonized. They work on different principles and communication between professionals working in the two fields is insufficient, even when justified by the interests of the user. Home nursing financed by health insurance is a short-term support (14 days, with an option to be extended to a maximum of 56 days). Getting a family member diagnosed with dementia is a very difficult process, and information is lacking.

According to estimates, less than half the people living with dementia have access to any kind of health or social service [

45]. Due to the care deficit and inadequacy of the nursing fee, family carers who are not already retired are usually forced to remain in the labour market even if they are full-time carers. Employed family carers are entitled to a maximum of two years of unpaid leave from work.

There is no official data on the number of migrant care workers in the Hungarian LTC system, although it is known from qualitative studies that informal caregivers coming from the Hungarian minorities of neighbouring Romania and Ukraine do provide live-in care for frail older people, including those with dementia [

49].

1.4. Severity of Health Crisis and Public Measures Implemented to Face the Pandemic

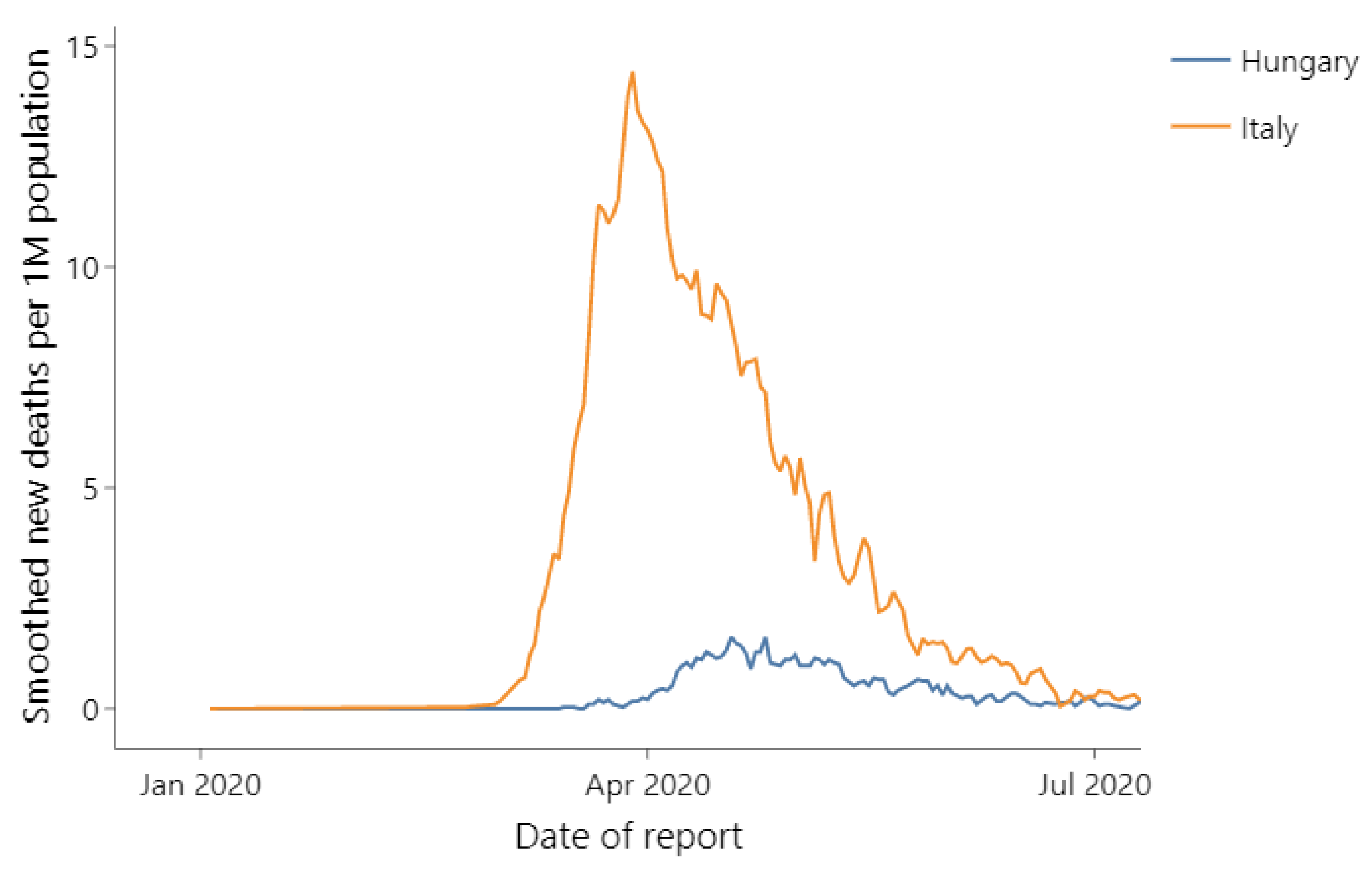

Figure 1 shows new coronavirus-related deaths in Italy and Hungary (three-day smoothing window) between January and July 2020 [

1].

European governments implemented a wide range of responses and measures to tackle the pandemic which served, in part, to shield older adults from the virus. However, these also had adverse side effects, including increased social isolation, economic difficulties, delayed medical treatment and challenges to get basic needs met [

19]. Several countries reported a reduction in community services, either in order to protect care recipients from contracting SARS-CoV-2 virus, or due to general regulations to close down certain services for the pandemic period [

27].

These measures may also have affected the mental health and well-being of family carers, the population group providing the bulk of care to older people. This problem might have been exacerbated due to the fact that migrant care workers in many cases reduced or stopped providing support to family carers [

50,

51].

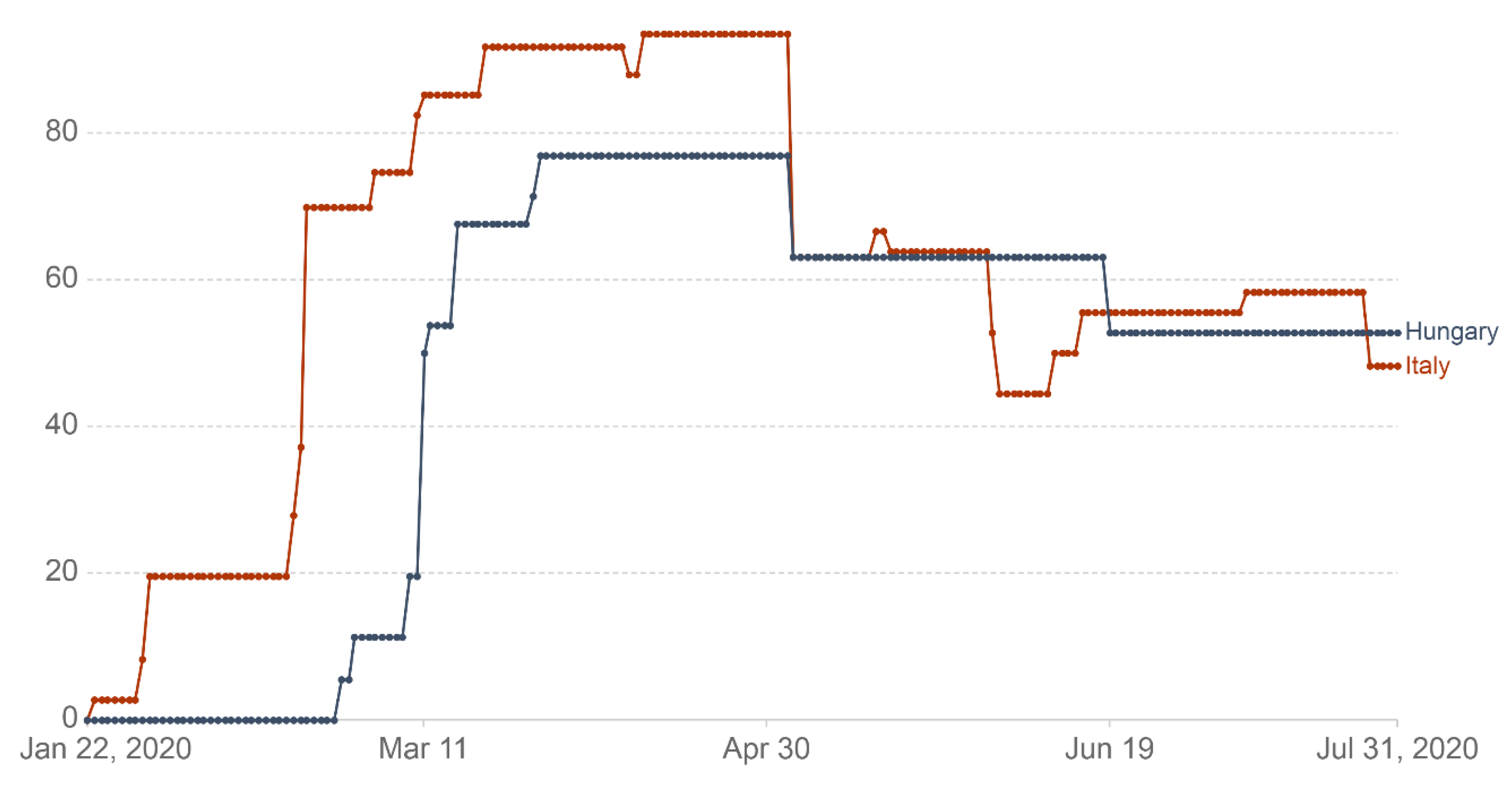

The Government Response Stringency Index [

52] is used here to indicate the strictness of “lockdown-style” policies adopted in Italy and Hungary (

Figure 2). The index provides a systematic, cross-national, cross-temporal measure aimed at understanding how government responses evolved over the period of the disease’s spread. The index, which has a value from 0 to 100 (100 = strictest response), is a composite measure of nine response indicators including school closures, workplace closures and travel bans, recording the strictness of government policies.

On the date the WHO declared COVID-19 a pandemic (11 March 2020), Italy was the only country in Europe with a high stringency index score (85.9), with the next four countries (including Hungary) having scores between 40 and 50, while other European states had even lower scores.

Figure 2 shows that the Italian government adopted a more restrictive set of measures between January and July 2020, being the first European country to put a comprehensive lockdown in place. The stringency of measures enacted by governments increased sharply in both countries, reaching a peak in April 2020 and then dropping significantly in early May, to substantially stabilize in the following months, albeit with some fluctuations.

Table 1 details the measures taken by the Italian and Hungarian governments [

53,

54,

55].

As shown in

Table 1, several measures were similar in Italy and Hungary, and correspond to different components of the stringency index (e.g., schools closing, public events cancelled, restrictions on gatherings and staying at home). However, there was no limitation on the use of transportation between municipalities in Hungary. In Italy, sports activities were not allowed outside the vicinity of one’s home, while in Hungary, individuals and persons living in the same household were allowed to exercise outside. Shopping from 9 a.m. until 12 a.m. was only permitted for those over 65 years of age in Hungary. In both countries, due to the spread of the virus and the related dramatic consequences especially affecting frail and older people, specific restrictions and limitations to the access of relatives and visitors to residential/nursing homes were established.

The declared state of emergency was much longer in Italy, initially spanning six months from 31 January until 31 July, then extended to 15 October and subsequently, to 31 January 2021 (and then, due to the “second wave” of the pandemic, to 31 July 2021). A state of emergency was declared in Hungary on 11 March 2020 and lasted until 18 June of the same year. The Italian responses might have been considered by the Hungarian government as it introduced a comprehensive stringency package, the instructions of which came into force simultaneously on 16 March 2020 instead of being gradually phased in.

In short, stringency measures during the first wave of the pandemic covered a shorter period in Hungary, concentrated mostly on the capital and the surrounding counties and, in general, citizens enjoyed more freedom than in Italy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

Due to the difficulty of reaching the target group, as well as restrictions related to the pandemic, the online questionnaire designed for this study was distributed in both countries via social media channels (self-help Facebook groups of family carers of people with dementia). Keywords used for finding the appropriate Facebook groups were: Alzheimer’s, dementia, Parkinson, carers’ self-help groups and day care centres. The link to the questionnaire was shared in 33 Italian Facebook groups and pages with a total of 43,566 members, and in six Hungarian Facebook groups with a total of 11,344 members. Data was collected between May and July 2020.

2.2. Questionnaire

The survey consisted of questions related to the socio-demographic background of both the family caregiver and the person being cared for; aspects of the caregiver-care recipient relationship (and pandemic-related changes in this relationship); caregiver’s responsibilities; caregiver’s self-reported physical, general and mental health status, including the level of stress experienced due to the pandemic; the type and source of help the caregiver received with care-related activities, both before and after the declared state of emergency; the types of physical and mental resources caregivers were able to utilize in order to cope with the difficulties posed by the pandemic; and, helping factors and problems in carrying out care tasks. The questionnaire was presented in its original form (in Hungarian) to Hungarian respondents, and was translated into English and then, after cross-checking, from English into Italian for the Italian audience.

2.3. Sample

Selection criteria in both countries included being the primary family carer, present and active on social media channels described in the Data collection section above, of a person with dementia living at home before the COVID-19 lockdown. Caregivers of dementia patients who were already living in nursing homes, as well as caregivers who were not family members, were excluded from the sample.

The sample consisted of 188 Italian and 182 Hungarian respondents (88% female and 12% male) with an average age of 54 years, which is in line with the literature in terms of long-term home care of older persons [

56,

57,

58], and results concerning informal carers of people living with dementia [

47,

50]. Nearly all respondents (90% of the Italian and 99% of the Hungarian respondents, respectively) were educated at least up to secondary level, and most of them (64%) lived in cities—although this number was notably smaller in the Italian sample where 49 per cent reported living in rural areas or villages. Most respondents (69%) reported being married or in a relationship, whereas 31% reported being single, widowed, or divorced. Most respondents were either the child (73%) or the partner (17%) of the person being cared for, and more than half of them (58%) lived together with the older person with dementia before the pandemic (although this number was significantly higher among Hungarian respondents than among Italian ones, 65% and 52%, respectively). Among the family carers participating in the study 66% reported being currently employed. Over half (54%) the respondents reported that the person they cared for was 80 years of age or more, with another one-third (32%) reporting an age of between 70 and 79 years. Around 15% of family carers were caring for someone younger than 70 years of age.

2.4. Statistical Data Analysis

Chi-squared tests with standardized adjusted residuals and Mann–Whitney U tests were used to compare results in the Italian and Hungarian samples. McNemar’s tests were run to see changes in the types and sources of care-related help family carers received before and after the declared state of emergency. The software used for running statistical analyses was SPSS Statistics (version 24.0.0.0, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Occupational Status of Family Carers

Professional occupations were the most commonly mentioned occupational category (25%), however, the rest of the categories were more divided by country: 24% of the Italian and only 4% of the Hungarian respondents indicated working as clerical support workers, whereas 4% of the Italian and 15% of the Hungarian sample mentioned working as technicians and in associated professional roles. The difference was also substantial within the inactive categories: in the Hungarian sample, 24% reported being retired and 1% being a homemaker, while these numbers were 15% and 12% in the Italian sample. The higher share of retirees in the Hungarian sample (despite the same average age) might be explained by an “early exit culture”, characteristic of post-socialist countries [

59], which started during the recession following the transition from socialism to democracy.

The higher number of homemakers in the Italian sample is most likely related to the fact that women make up most of the sample. The inactivity rate of Italian women aged 20 to 64 is higher than that of Hungarian women (53% compared to 67%, 2018 data) [

60].

3.2. Severity of Dementia of the Person Cared for

In the Hungarian sample, 14% reported not knowing or not having a diagnosis for the severity of the patient’s dementia, which is significantly higher than the 5% in the Italian sample. The rest of the respondents declared either medium (44%) or high (42%) self-reported severity of dementia. However, high severity was significantly more common in the Italian sample (52% versus the 32% in the Hungarian sample) and 86% of respondents had been caring for their relative for over one year (with Italians reporting significantly longer times). The median weekly care time is 24 h, although this number is significantly higher in the Italian (50 h) than in the Hungarian sample (14 h).

3.3. Care-related Tasks of Family Carers, and the Effect of Country and Severity of Dementia

Family carers were asked to select their care-related tasks from a list. The following six types of activities had a very high share (exceeding 80%) in the Hungarian sample: shopping, medicine administration, dealing with official matters, cooking, conversation with the person living with dementia and cleaning/washing. Only three of the tasks (shopping, administration of drugs and sorting out official matters) had a similarly high incidence rate in the Italian sample.

Associations of dementia by country and severity were examined in relation to each care activity (

Table 2). Some care activities were not associated with either: shopping, administering medicine, managing official matters and tasks in the “other” category were mentioned in similar numbers in both samples and for both categories of dementia (severe vs. mild/moderate). Some care activities were only associated with the country and not with the severity of dementia: more Hungarian than Italian family carers reported conversing with the person they cared for, cleaning and washing, cooking, and taking care of jobs around the house. On the other hand, bathing the patient and changing diapers were only associated with severity (more severe cases had a higher incidence rate) and not with the country.

In two types of care responsibilities, country and severity of dementia were both associated with the incidence rate. Feeding the patient was one of these: it was reported in higher proportions in the Hungarian sample, and family carers with more severe cases reported this activity in larger numbers in both countries. Patient movement was the other responsibility, however, severity of dementia had a different effect here depending on the country. This task was generally mentioned more frequently by Italian carers and in this sample, categories of severity made no significant difference. However, in the Hungarian sample, over five times as many family carers with severe cases reported doing this task, compared to those with mild/moderate cases.

3.4. Changes in Employment and Financial Status

Some kind of change in the employment status due to the pandemic was experienced by 52% of the Italian sample and by 31% of the Hungarian one, the most common of which was “having to work from home” (reported by 23%, no significant difference between the two samples). In terms of financial status, nearly one-third (29%) of respondents were affected negatively as a result of caring for family members with dementia during the COVID-19 outbreak, with Italian respondents experiencing more severe difficulties (21% experiencing severe and 3% mild financial difficulties, compared to 4% and 23% in the Hungarian sample, respectively). The higher rate of change in employment status and the higher severity of financial difficulties in the Italian sample seem to be caused by two aspects: first, Italian respondents being more affected by employment-related changes such as job loss, having to go on paid or unpaid leave and having to switch to part-time work (each instance under 10%); second, a higher rate of retirees in the Hungarian sample, whose income remained unaffected by changes in the labour market. The financial difficulties of Italian family carers were also exacerbated by the fact that they could not use the cash-for-care benefit on caregiving activities due to the unavailability of migrant care workers and having to pay for all care-related expenses out of their own pockets.

3.5. Changes in Caregiver-Care Recipient Relationship, and the State of the Person Cared for

Most respondents (88%) reported no change in cohabitation with the person they cared for, and a little less than one out of 10 mentioned having moved in with them. Since the emergency measures came into place, 60% experienced an increase in weekly care-time, and 35% reported no change. The Italian group reported a deterioration in the state of health of the person they care for in significantly higher numbers (61%) compared to Hungarian respondents (37%). Emotional disturbances (mood changes, aggression and apathy) and difficulties related to COVID-19 (fear of being infected, excessive proximity, confinement and narrowing of the range of activities) were more prevalent among Italian respondents, whereas cognitive impairment (not recognizing family members, confusion and mental state) and physical deterioration were more commonly reported by the Hungarian group.

3.6. Changes in the State of Health of Family Carers

Half of all respondents reported good, and one out of 10 of them poor pre-pandemic general health (with the rest of the sample falling in between). During the first wave of the COVID-19 outbreak, both general and mental health deterioration were more prevalent in the Italian (41% and 55%) than in the Hungarian sample (26% and 39%).

3.7. Care-related Help Received before and during the First Wave of the Pandemic

The majority of Italian and Hungarian respondents received some kind of help before the pandemic (82% and 80%, respectively;

Table 3). This decreased in both countries after the COVID-19 outbreak. Slightly more than half of the Italian sample indicated having received help (57%) during the first wave, while the rate in the Hungarian sample remained higher (70% among those with valid responses to both questions). The change between the two periods was significant in both countries, but Italy saw a much larger decrease (by 25 percentage points (pp) compared to 10 pp in Hungary).

3.8. Changes in the Types of Help since the COVID-19 Outbreak

Before the declaration of the state of emergency, family carers in the Italian sample compared with the Hungarian one indicated the following categories with high rate: maintaining the personal hygiene of the person cared for (42%, Hungarian sample 24%); housework (washing, cleaning, cooking) (42%, Hungarian sample 17%).

Family carers in the Hungarian sample indicated with somewhat higher rate: daycare (35%, Italian 27%); emotional support (33%, Italian 27%); communication and conversation with the person cared for (32%, Italian 18%).

The following categories were indicated below 20% in both samples: 24-hour supervision (Italian sample 19% and Hungarian 10%); nursing activities (9% and 17%); all-night supervision (13% and 10%) and financial support (4% and 6%).

As can be seen, the most widespread types of help in the Italian sample were maintenance of personal hygiene and housework, while daycare, emotional support and conversation were leading the list of the Hungarian sample.

In both samples, 13% reported not receiving any help despite needing it, while 6% in the Italian and 12% in the Hungarian sample stated that they didn’t need any sort of care-related help.

However, due to low cell-counts and in order to be able to run statistics to see changes, types of care-related help were collapsed into larger categories such as help with everyday tasks (housework, personal hygiene of the person cared for, daycare), specialized care (night duty, 24 h duty, nursing activities) and mental health support (conversation, communication, emotional support). The categories of “did not need help” and “did not get help despite needing it” were also merged and called I didn’t get help (see

Table 4).

One type of care-related help (financial support) did not meaningfully fit into any of the larger categories, and was therefore left out from

Table 4.

In the Italian sample, all categories of help received saw a significant decrease: everyday tasks (−31 pp), mental health support (−23 pp), and specialized care (−9 pp). In the Hungarian sample, only one of the categories of help saw a significant decrease (everyday tasks, −11 pp). As a logical consequence of family carers receiving less help after the outbreak, those with no care-related help grew in number, but the increase was much more severe among Italian carers (+30 pp) than among Hungarians (+9 pp).

3.9. Changes in the Sources of Help during the First Wave of the COVID-19 Outbreak

There was a long list of categories in the questionnaire from whom family carers could receive help. In both countries help from family had the highest rate (46% in the Italian and 56% in the Hungarian sample). Family doctors in both countries played an important role as well (25% and 20%). However, a great difference can be seen in the category of social service provider, in that case Hungary preceded Italy (20%, Italian 8%). In the Italian sample specialist doctors were important source of help as well (17% and 11%). We should underline that in the Italian sample compared with the Hungarian one non-cohabiting private care workers (12% and 4%) and cohabiting private care workers (12% and 1%) had much higher ratio. Day-care centres were indicated only in the Italian sample (17%). Other categories were mentioned below 10% in both countries.

It was inevitable to collapse categories into larger ones such as: family; healthcare providers (family doctor, medical assistant, specialist, ambulance); social services (service providers, council, daycare centre); voluntary help (friends, neighbours, colleagues, charities, volunteers, telephone helpline), paid help (cohabiting or non-cohabiting care workers) (

Table 5).

As we can see, the utilized help-sources show a very similar pattern in the two samples: family was the most prevalent category, followed by healthcare providers, social services, and voluntary help. The category where the two samples differ greatly is that of paid help, utilized by 25% of Italian, and by only 5% of Hungarian family carers. This difference of pattern is worth keeping in mind when interpreting changes brought on by the pandemic. In terms of the collapsed categories, the Italian sample saw a significant decrease in the utilization of social services (−18 pp), healthcare providers (−15 pp), paid help (−10 pp), and family members (−9 pp). In the Hungarian sample, significantly less caregivers received help from healthcare providers (−9 pp), social services (−6 pp), and paid help (−5 pp) (

Table 5).

4. Discussion

The ongoing pandemic is having a profound impact on people with dementia and their caregivers. During the first wave of the COVID-19 outbreak, Italian caregivers experienced a decrease in more types and sources of care-related help than Hungarian ones, as well as a higher drop in the utilization of help in general. The increase in those not getting needed assistance was more than threefold in the Italian sample. One of the factors possibly explaining the discrepancies in changes is the different cluster of care regimes the two countries belong to (taking in consideration the situation during the first wave of the pandemic): Italy’s weak resilience in informal care and moderate resilience in formal care provision versus Hungary’s weak resilience in both formal and informal care. Our results reflect some of these features. For example, higher pre-pandemic utilization of paid care (mainly home-based migrant care workers) in Italy is likely due to the strong cash-for-care focus characterizing the Italian LTC system. This type of cash-for-care setup (which uses vouchers and care allowances as the main source of support to community dwelling dependent people) is not available in the Hungarian model.

Another factor to take into account is the nature of pandemic-related restrictions and regulations in the two countries. The fast and overwhelming manifestation and spread of the virus in Italy caused an early interruption of care activities due to the fear of contagion by family members. As the pandemic grew more serious, the usually available support systems (paid care workers, social services and healthcare provisions) got more difficult to access and eventually became partly unavailable. Before the pandemic, health and social services provided help; after the outbreak, the governments of both countries limited the availability of both health care services (e.g., ban of doctor-patient appointments, postponement of examinations and non-life-saving surgeries) and social services (e.g., closing down of daycare centers, lockdown of residential and nursing homes). This naturally had an effect on the utilization of help resources, but not in the same way in the two countries. For example, some restrictions were stricter and effectively longer in Italy (e.g., ban on moving between municipalities), which resulted in the drop-out of paid care workers, especially migrant care workers (“badanti”) as helping hands. Unavailability of migrant care workers may also partly explain the more serious financial difficulties reported by Italian respondents, since not being able to spend the allowance on “badanti” forced family carers to pay for services bought in the more expensive private care market out of their own pocket.

More severe austerity measures might also explain why more Italian family carers reported a drop in help received from family members; it is important to note, however, that family has remained by far the most important source of support in both samples, even after the outbreak. Concerning austerity measures, the most rigid and comprehensive lockdown put in place in Italy certainly negatively affected the provision of health and social care services to the Italian sample of family carers and their care recipients.

As stated, caregivers experienced an increase in their psychological and physical burden during the pandemic, especially due to the limited availability of resources to support their care-related tasks. Similarly, the reduction in the supply of health and social care services (including the closure/shorter opening hours of day centres for cognitive disorders and Alzheimer’s/dementia) probably contributed to the deterioration of the health of family carers as demonstrated by the study’s results. The fact that both the utilization of non-family helpers and the strictness of austerity levels were higher in Italy than in Hungary might explain why both general and mental health deterioration were more prevalent in the Italian sample.

According to a survey of the Italian National Institute of Health [

61], the organization and provision of services dedicated to people with dementia and to their family carers were not evenly distributed throughout Italy, with a greater offer in the Northern regions and a lesser provision or no access in the Southern areas of the country. For instance, 78% of day care centres are located in the North, 14% in the Centre and 8% in the South and islands [

61]. This highlighted an inadequate coverage of available support services, calling for policy action and initiatives aimed at filling this gap, as well as the improvement in the supply of support services to even out the availability of services within the country. Country-wide implementation of the National Dementia Plan [

62]—a strategic document for governing the phenomenon of dementia in the Italian territories approved in 2014 but not currently implemented in all Regions—might be one way to achieve this goal. Initiatives and publications have recently been put in place to provide healthcare professionals and caregivers with practical information on preventing COVID-19 infection, and to provide support to people living with dementia in times of a pandemic [

63].

5. Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the weaknesses of support structures for family carers of people living with dementia, in Italy as well as in Hungary. Before the COVID-19 lockdown, Italian family carers relied mostly on help from (migrant) paid care workers, daycare centers and services available through municipalities in order to support their older relatives living with dementia. The interruption or strong reduction in healthcare and social support services, as well as the closure of daycare centers, adopted to contain the pandemic, made many family carers feel extremely overwhelmed. Families relying heavily on the migrant workforce saw a further decrease in support, since migrant care workers were limited in their free movement, as in many cases they were unable to justify their need to move freely due to working on an undeclared basis. Therefore, migrant care workers reduced or temporarily stopped providing their services. Families were also fearful of care workers possibly infecting their frail family members, leaving families alone in their struggle to provide appropriate care to their members affected by dementia.

The Hungarian system was generally not well-prepared from the outset to ease the burden that typically concerns families caring for people affected by dementia: to have a family member diagnosed is difficult, health and social care systems are not harmonized, the cash-benefit (nursing fee) is inadequate, and there is a lack of services specifically aimed at people living with dementia. However, as the structure is mainly made up of local actors and the families themselves, it is less vulnerable to border closures. Still, there is limited information available on people with dementia and the families taking care of them, especially if the illness is not diagnosed, in which case they are invisible to social and health care systems. The lack of systematic data collection and statistical analysis on people living with dementia and their caregivers in both countries (especially in Hungary) is a substantial obstacle to developing targeted policies that fit to the needs of this population group. In this regard, there is a clear need for representative studies investigating family (and informal) carers, including comprehensive information on possible sources of help. A good example of this is the UK database for family carers managed by the Alzheimer’s Society, where carers can make their needs visible to councils, social and healthcare service providers, and can be asked to participate in research. The easily accessible information on the website, as well as the telephone helpline, helps carers find local support services.

In order to face the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic and learn out of them to make care systems (in Hungary and Italy, as well as at international level) more sustainable for the future, it is essential to strengthen families caring for dementia patients. Support structures need to be re-evaluated and developed, alternative forms of support mapped out or created to supplement the services already available, and methods and tools customized specifically to the needs of this group. When designing new support structures, policymakers need to take into account that pandemics, such as COVID-19, are predicted to become more common, and support systems will need to be working under the resulting circumstances. Similarly, when adopting restrictive measures, governments cannot overlook the specific vulnerabilities characterizing their social and health care systems and have to make sure that citizens can still access the services they need. In this regard, the clustering of country-specific strengths and weaknesses, as indicated above, may well represent a useful strategy to identify solutions to tackle crucial care challenges like the one of dementia related care in a sustainable, country-sensitive way.

Limitations of the Present Study

This paper has some limitations that need to be considered. One of these is that family carers of older people with dementia are a hidden target group, and tracing family carers in a crisis as serious as the COVID-19 pandemic is particularly difficult. Dementia is a taboo topic in many societies including Hungary and Italy, and carers are mostly isolated. Therefore, an online questionnaire was used, with respondents recruited from Facebook groups. As a result, family carers who do not use the Internet or Facebook, or are unaware of self-help groups, and who could have had different experiences and attitudes, could not be reached. Thus, the sample of our study does not intend to be representative of all family caregivers of people with dementia. The second limitation is directly related to the first: results cannot be considered representative of family carers of people with dementia in terms of socio-demographic characteristics. A third limitation is a relatively small sample size, forcing the research team to use collapsed categories in some of the statistical analyses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: L.Á.K., Z.S. and C.G.; methodology: L.Á.K., Z.S., V.E.A. and S.Q.; formal analysis: V.E.A. and P.F.; investigation: L.Á.K. and S.Q.; data curation: V.E.A., P.F. and S.Q.; writing—original draft preparation: L.Á.K., Z.S., V.E.A. and C.G.; writing—review and editing: L.Á.K., Z.S., V.E.A., M.S., C.G., S.Q., P.F. and G.L.; visualization: L.Á.K., Z.S. and M.S.; supervision: Z.S. and C.G.; project administration: L.Á.K., Z.S. and C.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partially supported by Ricerca Corrente funding from Italian Ministry of Health to IRCCS INRCA. This funding body did not play any role in designing the study nor in data collection, analysis and interpretation, nor in writing this paper.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Scientific and Research Committee of the Medical Research Council of Hungary (IV/11068-1/2020/EKU) on the 30 December 2020.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is not yet publicly available, but is planned to be made available at the end of 2021.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank all family carers who kindly accepted to contribute to this survey and thus to enhancing our understanding of their needs and challenges experienced during the first wave of the pandemic and possible solutions to meet them. Moreover, they are grateful to all the Facebook groups and pages who accepted to share and host the link to the online questionnaire.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. WHO COVID-19 Explorer; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://worldhealthorg.shinyapps.io/covid/ (accessed on 23 January 2021).

- Tur-Sinai, A.; Bentur, N.; Lamura, G. Impact of the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic on the formal and informal care of community dwelling older adults: A cross-national clustering of empirical evidence from 23 countries. Unpublished manuscript.

- Esping-Andersen, G. Social Foundations of Postindustrial Economies; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999; p. 218. [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann, M.; Wagner, M. Caregiving and Care Receiving Across Europe in Times of COVID-19. SHARE Working Paper Series 59-2021; Munich Center for the Economics of Aging (MEA): Munich, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Dementia: A Public Health Priority; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012; Available online: http://www.who.int/mental_health/publications/dementia_report_2012/en/ (accessed on 18 January 2021).

- Zarit, S.; Orr, N.K.; Zarit, J.M. The Hidden Victims of Alzheimer’s Disease: Families Under Stress; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995; p. 238. [Google Scholar]

- United Kingdom Department of Health. Living Well With Dementia: A National Dementia Strategy; Department of Health: London, UK, 2009; p. 102. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, D.; Vass, C.; Aubeeluck, A. Quality of Life on the Views of Older Family Carers of People with Dementia. Dementia 2017, 18, 990–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ory, M.G.; Hoffman, R.R.; Yee, J.L.; Tennstedt, S.; Schulz, R. Prevalence and impact of caregiving: A detailed comparison between dementia and nondementia caregivers. Gerontologist 1999, 39, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brodaty, H.; Donkin, M. Family caregivers of people with dementia. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2009, 11, 217–228. [Google Scholar]

- Hooker, K.; Bowman, S.; Coehlo, D.P.; Lim, S.R.; Kaye, J.; Guariglia, R.; Li, F. Behavioral Change in Persons With Dementia: Relationships With Mental and Physical Health of Caregivers. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2002, 57, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vitaliano, P.P.; Zhang, J.; Scanlan, J.M. Is Caregiving Hazardous to One’s Physical Health? A Meta-Analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 946–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kröger, T.; Yeandle, S. Combining Paid Work and Family Care: Policies and Experiences in International Perspective; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2013; p. 264. [Google Scholar]

- Socci, M.; Principi, A.; Di Rosa, M.; Carney, P.; Chiatti, C.; Lattanzio, F. Impact of working situation on mental and physical health for informal caregivers of older people with Alzheimer’s disease in Italy. Results from the UP-TECH longitudinal study. Aging Ment. Health 2021, 25, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Italian Alzheimer’s Disease Association and CENSIS Foundation (Associazione Italiana Malattia di Alzheimer and Fondanzione CENSIS). L’impatto Economico E Sociale Della Malattia Di Alzheimer: Rifare Il Punto Dopo 16 Anni; Fondazione CENSIS: Rome, Italy, 2016; p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda, S. Family Care Leave and Job Quitting Due to Caregiving: Focus on the Need for Long-Term Leave. Japan Labor. Rev. 2017, 14, 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, G.C.; Tobin, S.S.; Robertson-Tchabo, E.A.; Power, P.W. (Eds.) Strengthening Aging Families: Diversity in Practice and Policy, 1st ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995; p. 304. [Google Scholar]

- Cacciapaglia, G.; Cot, C.; Sannino, F. Second wave COVID-19 pandemics in Europe: A temporal playbook. Sci. Rep. UK 2020, 10, 15514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, E.A. Protecting and Improving the Lives of Older Adults in the COVID-19 Era. J. Aging Soc. Policy 2020, 32, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giebel, C.; Cannon, J.; Hanna, K.; Butchard, S.; Eley, R.; Gaughan, A.; Komuravelli, A.; Shenton, J.; Callaghan, S.; Tetlow, H.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 related social support service closures on people with dementia and unpaid carers: A qualitative study. Aging Ment. Health 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barry, H.E.; Hughes, C.M. Managing medicines in the time of COVID-19: Implications for community-dwelling people with dementia. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. Net. 2020, 43, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, R.; Simmons, C.; Schmidt, A.E.; Steiber, N. Care in times of COVID-19: The impact of the pandemic on informal caregiving in Austria. Eur. J. Ageing 2020, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaitheswaran, S.; Lakshminarayanan, M.; Ramanujam, V.; Sargunan, S.; Venkatesan, S. Experiences and Needs of Caregivers of Persons with Dementia in India During the COVID-19 Pandemic—A Qualitative Study. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 1185–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, G.; Russo, M.J.; Campos, J.A.; Allegri, R.F. COVID-19 Epidemic in Argentina: Worsening of Behavioral Symptoms in Elderly Subjects with Dementia Living in the Community. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsapanou, A.; Papatriantafyllou, J.D.; Yiannopoulou, K.; Sali, D.; Kalligerou, F.; Ntanasi, E.; Zoi, P.; Margioti, E.; Kamtsadeli, V.; Hatzopoulou, M.; et al. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on people with mild cognitive impairment/dementia and on their caregivers. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 36, 583–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Family Carers Ireland. Caring Through Covid: Life in Lockdown; Family Carers Ireland: Dublin, Ireland, 2020; p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Carers UK. Caring behind Closed Doors: Forgotten Families in The Coronavirus Outbreak; Carers UK: London, UK, 2020; p. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Rothgang, H.; Wolf-Ostermann, K.; Domhoff, D.; Franziska, H.; Heß, M.; Kalwitzki, T.; Ratz, K.; Schmidt, A.; Seibert, K.; Stolle, C.; et al. How Covid-19 Has Affected Informal Caregivers and Their Lives in Germany. 2020. Available online: https://ltccovid.org/2020/09/20/how-covid-19-has-affected-informal-caregivers-and-their-lives-in-germany/ (accessed on 27 January 2021).

- Giebel, C.; Hanna, K.; Cannon, J.; Eley, R.; Tetlow, H.; Gaughan, A.; Komuravelli, A.; Shenton, J.; Rogers, C.; Butchard, S.; et al. Decision-making for receiving paid home care for dementia in the time of COVID-19: A qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, G.; Russo, M.J.; Campos, J.A.; Allegri, R.F. Living with dementia: Increased level of caregiver stress in times of COVID-19. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2020, 32, 1377–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tróbert, A.; Bagyura, M.; Széman, Z. Családi gondozók és idősellátás a COVID-19 idején (Family Carers and the care for older people in the time of COVID 19), 2020. In Proceedings of the XXIV conference of Apáczai Csere Days, Győr, Hungary, 19 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman-Casanova, J.M.; Dura-Perez, E.; Guzman-Parra, J.; Cuesta-Vargas, A.; Mayoral-Cleries, F. Telehealth Home Support During COVID-19 Confinement for Community-Dwelling Older Adults With Mild Cognitive Impairment or Mild Dementia: Survey Study. J. Med. Internet. Res. 2020, 22, e19434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuffaro, L.; Di Lorenzo, F.; Bonavita, S.; Tedeschi, G.; Leocani, L.; Lavorgna, L. Dementia care and COVID-19 pandemic: A necessary digital revolution. Neurol. Sci. 2020, 41, 1977–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- sm-Rahman, A.; Lo, C.H.; Ramic, A.; Jahan, Y. Home-Based Care for People with Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias (ADRD) during COVID-19 Pandemic: From Challenges to Solutions. Int. J. Env. Res. Pub. Health 2020, 17, 9303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbrielli, F.; Bertinato, L.; De Filippis, G.; Bonomini, M.; Cipolla, M. Interim Provisions on Telemedicine Healthcare Services During COVID-19 Health Emergency. Version of April 13, 2020; Istituto Superiore di Sanità (Italian National Institute of Health): Rome, Italy, 2020; p. 38. [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer Europe. Dementia in Europe Yearbook 2019: Estimating the Prevalence of Dementia in Europe; Alzheimer Europe: Luxembourg, 2019; p. 108. [Google Scholar]

- Vetrano, D.L.; Vaccaro, K. Home Care in Italy: Who Does It, How to Do it and Good Practices; Italia Longeva: Rome, Italy, 2018; p. 72. [Google Scholar]

- Tidoli, R. Domicialirity. In Care of Non Self-Sufficient Older People in Italy. 6th Report, 2017–2018; NNA Network Non Autosufficienza, Ed.; Maggioli, S.p.A.: Sant’Arcangelo di Romagna, Italy, 2017; pp. 77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Barbabella, F.; Poli, A.; Chiatti, C.; Pelliccia, L.; Pesaresi, F. The compass of NNA: The state of the art based on data. In Care of Non Self-Sufficient Older People in Italy, 6th Report, 2017–2018; NNA Network Non Autosufficienza, Ed.; Maggioli, S.p.A.: Sant’Arcangelo di Romagna, Italy, 2017; pp. 33–54. [Google Scholar]

- Barbabella, F.; Chiatti, C.; Rimland, J.M.; Melchiorre, M.G.; Lamura, G.; Lattanzio, F. Up-Tech Research Group. Socioeconomic Predictors of the Employment of Migrant Care Workers by Italian Families Assisting Older Alzheimer’s Disease Patients: Evidence from the Up-Tech Study. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2016, 71, 514–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schmidt, A.E. Analysing the importance of older people’s resources for the use of home care in a cash-for-care scheme: Evidence from Vienna. Health Soc. Care Community 2017, 25, 514–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Luca, M.; Tronchin, C.; Di Pasquale, E. 2nd Annual Report on Domestic Work. Analysis, Statistics, National and Local Trends; Osservatorio Nazionale DOMINA sul Lavoro Domestico: Rome, Italy, 2020; p. 294. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlmann, E.; Greer, S.L.; Burau, V.; Falkenbach, M.; Jarman, H.; Pavolini, E. The migrant health workforce in European countries: Does anybody care? Eur. J. Public Health 2019, 29, ckz185-565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Italian Presidency of the Council of Ministers. Definizione dei Livelli Essenziali di Assistenza (Definition of Essential Levels of Assistance). Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana, Suppl. Ordinario alla Gazzetta Ufficiale n.33 del 08-02-2002—Serie Generale (Italian Official Gazette). 2002. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/gu/2002/02/08/33/so/26/sg/pdf (accessed on 25 January 2021).

- Gyarmati, A. Ageing and Care for the Elderly in Hungary; Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, Budapest Office: Buadapest, Hungary, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hungarian Parliament. 1993 III. Act on Social Administration and Social Benefits; Cabinet of Prime Minister: Budapest, Hungary, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Disability Affairs and Social Policy. Unified Disability Information Portal. 2021. Available online: https://www.efiportal.hu/szocialis-szolgaltatasok/alapszolgaltatasok/ (accessed on 26 January 2021).

- Hungarian Parliament. 1997 CLIV. Act on Healthcare; Cabinet of Prime Minister: Budapest, Hungary, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Széman, Z. Family Strategies in Hungary: The Role of Undocumented Migrants in Eldercare. J. Popul. Ageing 2012, 5, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz-Dant, K. Germany and the COVID-19 long-Term Care Situation; International Long Term Care Policy Network; CPEC-LSE: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, A.E.; Leichsenring, K.; Staflinger, H.; Litwin, C.; Bauer, A. The Impact of COVID-19 on Users and Providers of Long-Term Care Services in Austria; International Long Term Care Policy Network. CPEC-LSE, London, UK. 2020. Available online: https://ltccovid.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Austria-report-15-April-formatted.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2021).

- Hale, T.; Angrist, N.; Cameron-Blake, E.; Hallas, L.; Kira, B.; Majumdar, S.; Petherick, A.; Phillips, T.; Tatlow, H.; Webster, S. Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker, Blavatnik School of Government. 2020. Available online: https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/research/research-projects/coronavirus-government-response-tracker (accessed on 23 January 2021).

- Hungarian Government. Information Page on the Coronavirus. 2020. Available online: Koronavirus.gov.hu (accessed on 8 August 2020).

- Hungarian Ministry of Justice. Hungarian Official Gazette. 2020. Available online: https://magyarkozlony.hu/ (accessed on 8 August 2020).

- Italian Presidency of the Council of Ministers. Information Page on the Coronavirus. 2021. Available online: http://www.governo.it/it/coronavirus-misure-del-governo (accessed on 26 January 2021).

- Pinquart, M.; Sörensen, S. Spouses, Adult Children, and Children-in-Law as Caregivers of Older Adults: A Meta-Analytic Comparison. Psychol. Aging 2011, 26, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Genet, N.; Boerma, W.; Kroneman, M.; Hutchinson, A.; Saltman, R.B. (Eds.) Home Care across Europe: Current Structure and Future Challenges; World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2012; p. 156. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, N.; Chakrabarti, S.; Grover, S. Gender differences in caregiving among family—caregivers of people with mental illnesses. World J. Psychiatry 2016, 6, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorn, D.; Sousa-Poza, A. ‘Voluntary’ and ‘Involuntary’ Early Retirement: An International Analysis. Appl. Econ. 2010, 42, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Women’s Employment in the EU. 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/EDN-20200306-1 (accessed on 23 January 2021).

- Vanacore, N.; Salvi, E.; Palazzesi, I.; Pucchio, A.; Mayer, F.; Massari, M.; Marzolini, F.; Penna, L.; Mazzola, M.; Lacorte, E.; et al. Survey on the network of services in Italy. In XII Convegno. Il contributo dei Centri per i Disturbi Cognitivi e le Demenze nella Gestione Integrata de Pazienti; Italian National Institute of Health: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fiandra, T.; Canevelli, M.; Pucchio, A.; Vanacore, N. The Italian Dementia National Plan. Annali. Dell. Istituto. Super. Sanità. 2015, 51, 261–264. [Google Scholar]

- Italian National Institute of Health (Istituto Superiore di Sanità). Table for the monitoring and implementation of the National Dementia Plan. In Interim Indications for Appropriate Support for People with Dementia in the Current Scenario of the COVID-19 Pandemic; Italian National Institute of Health: Rome, Italy, 2020; p. 68. [Google Scholar]

| Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).