Social Capital as an Inclusion Tool from a Solidarity Finance Angle

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methodology

- The importance of the resources managed by the organization;

- Access to safe water and environmental sanitation is directly linked to life, human rights, and community wellness [77]); and

- The contribution of social capital to the organization’s sustainability.

- The representativeness of the case study as a collective action experience:

3. Results and Discussion

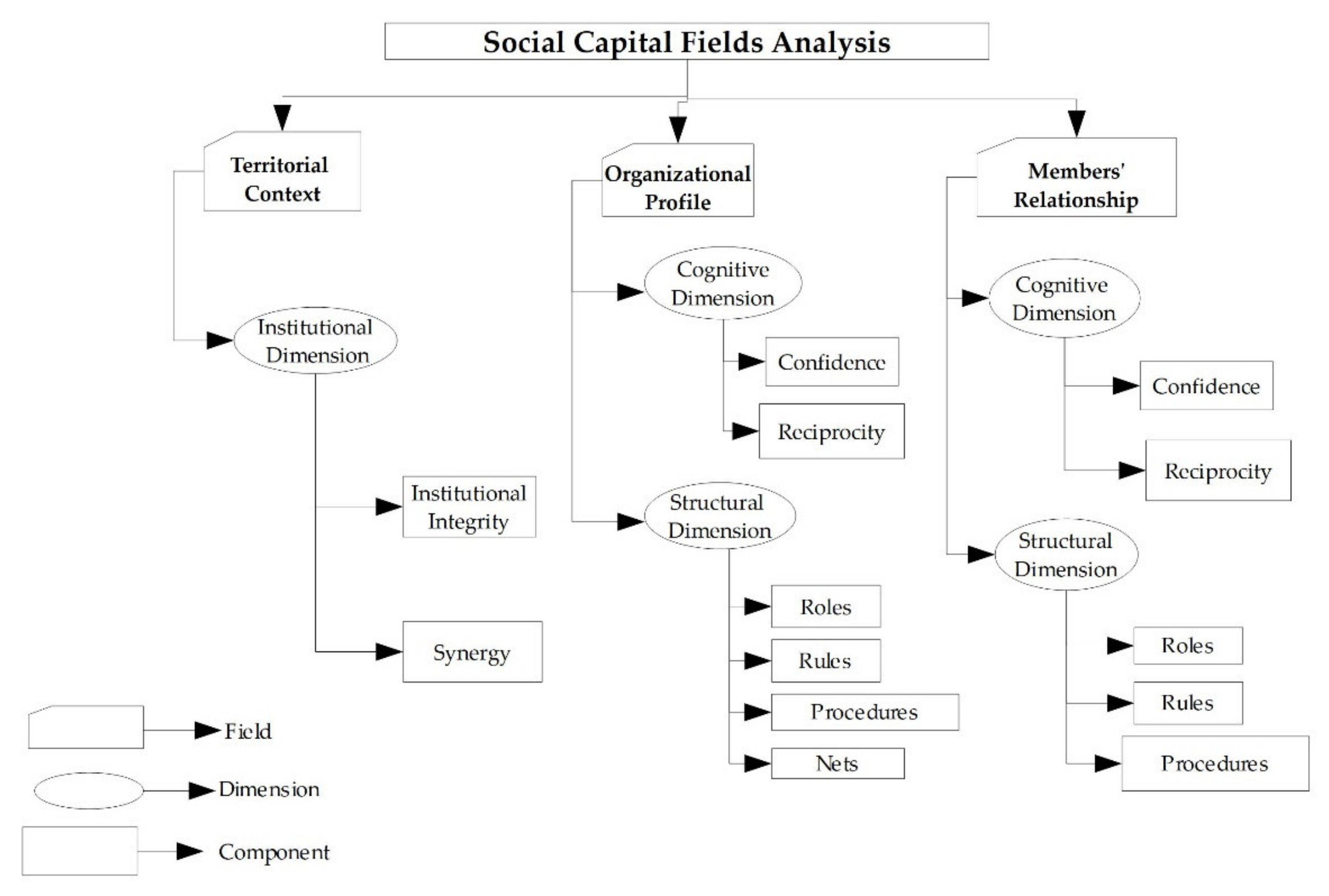

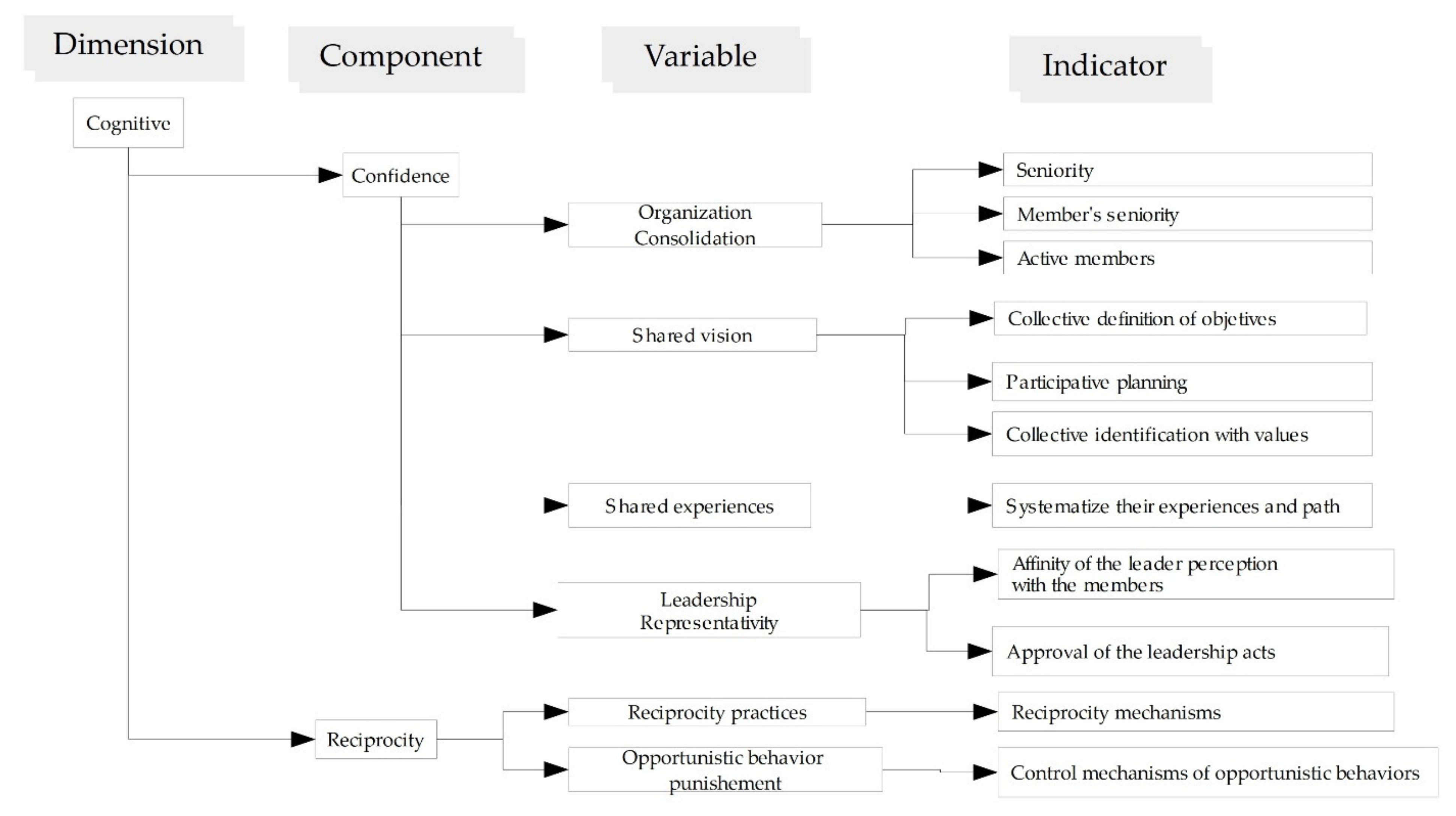

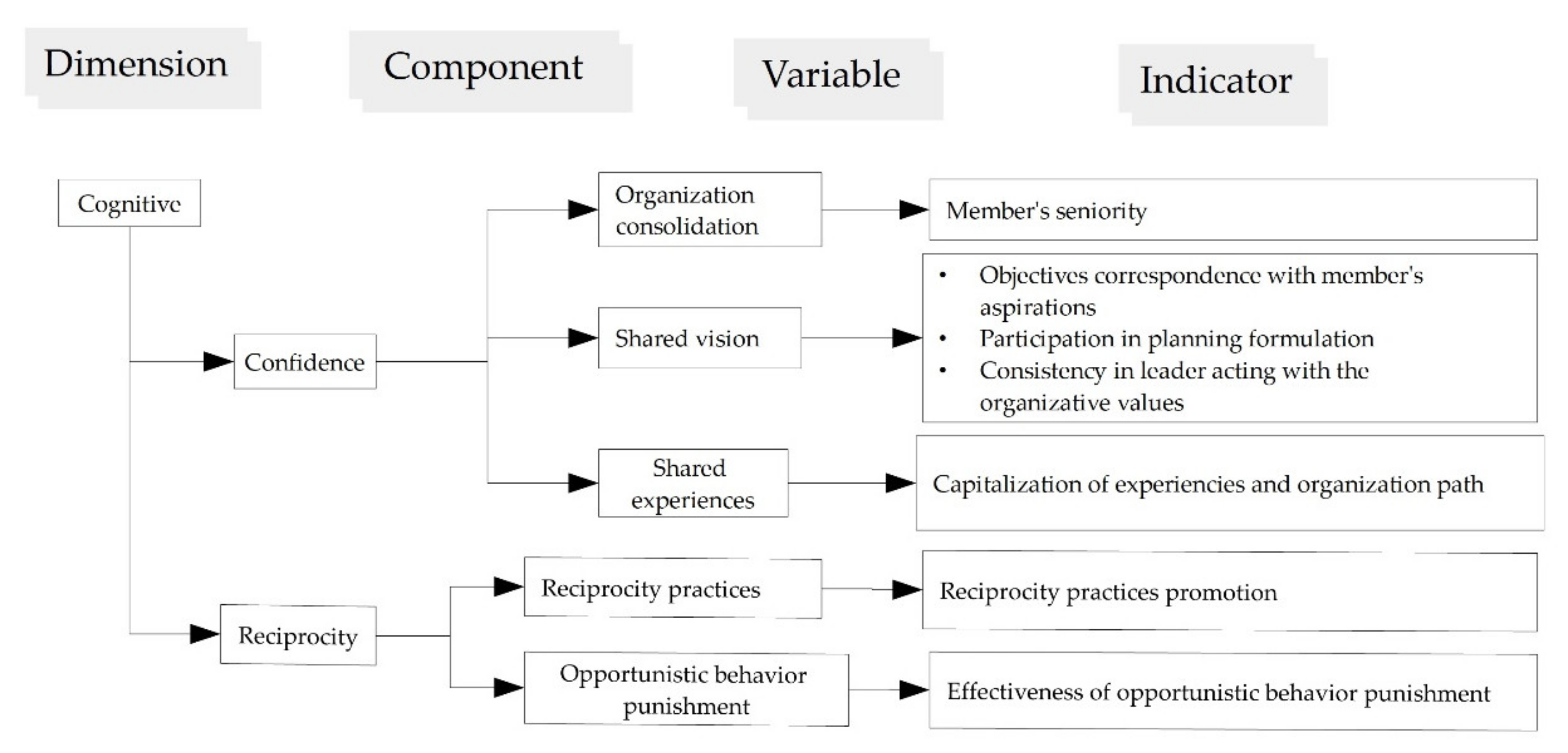

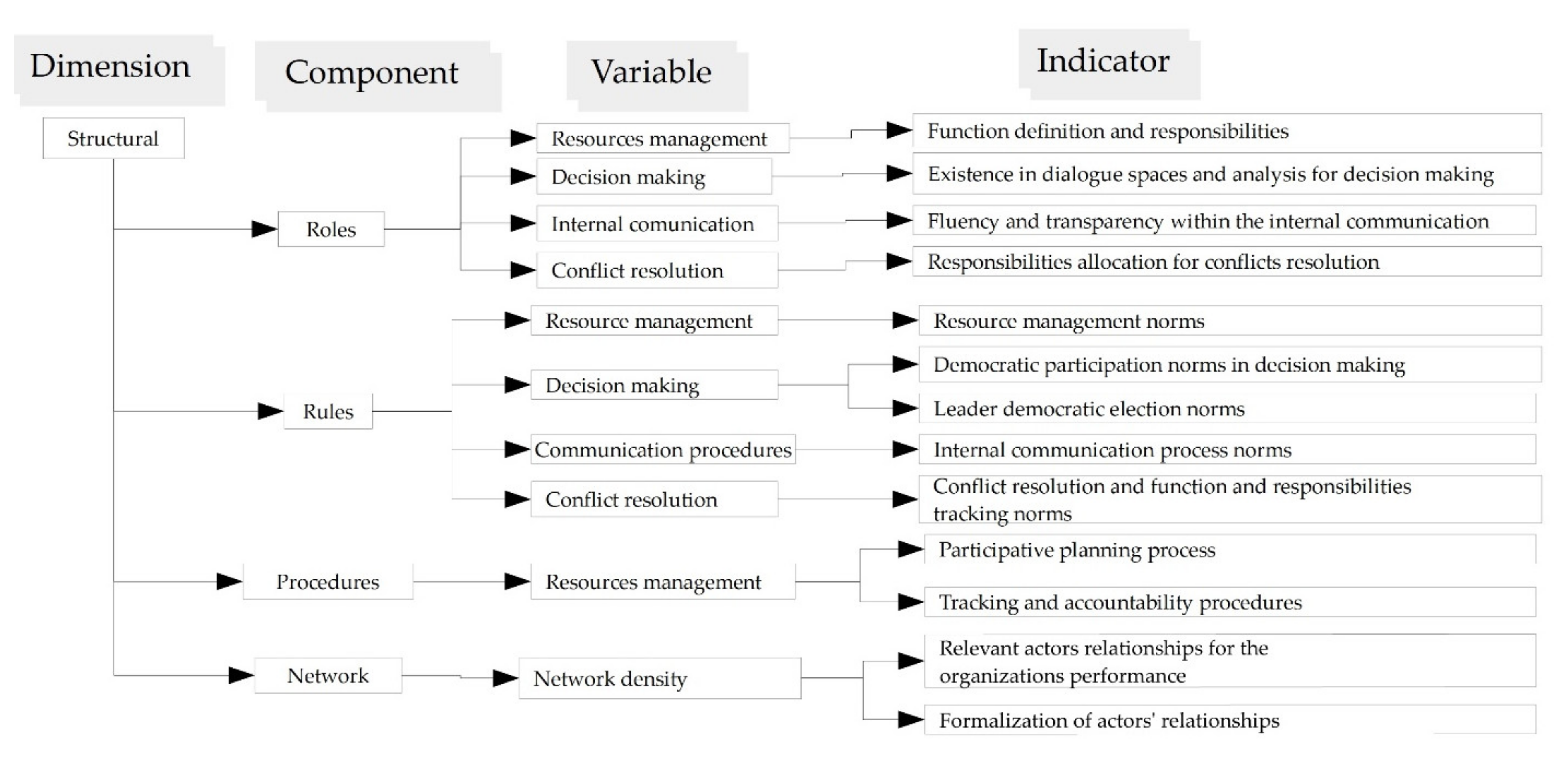

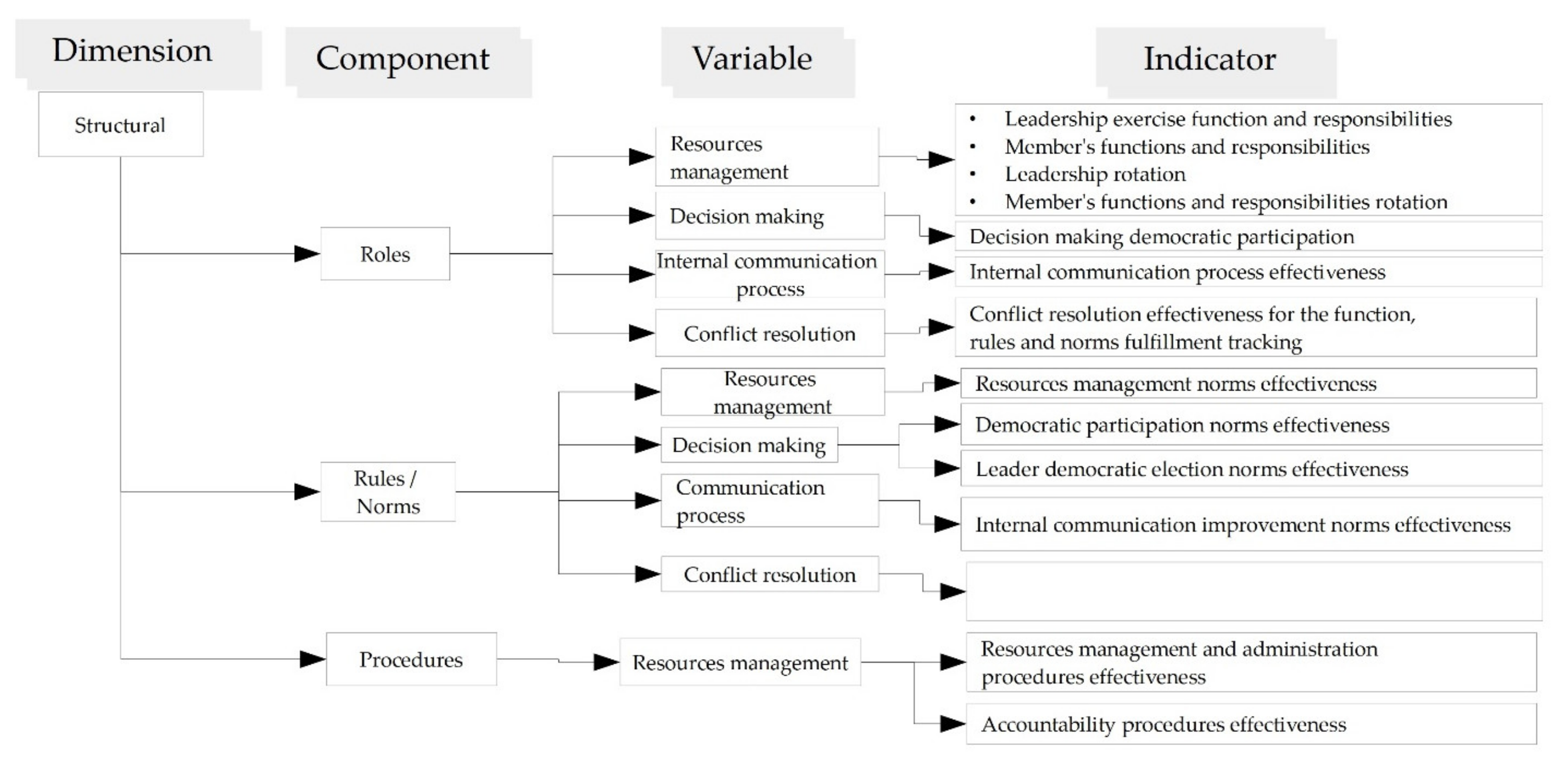

3.1. Analytical Approximation for Evaluating the Social Capital Endowment of Rural Production Organizations

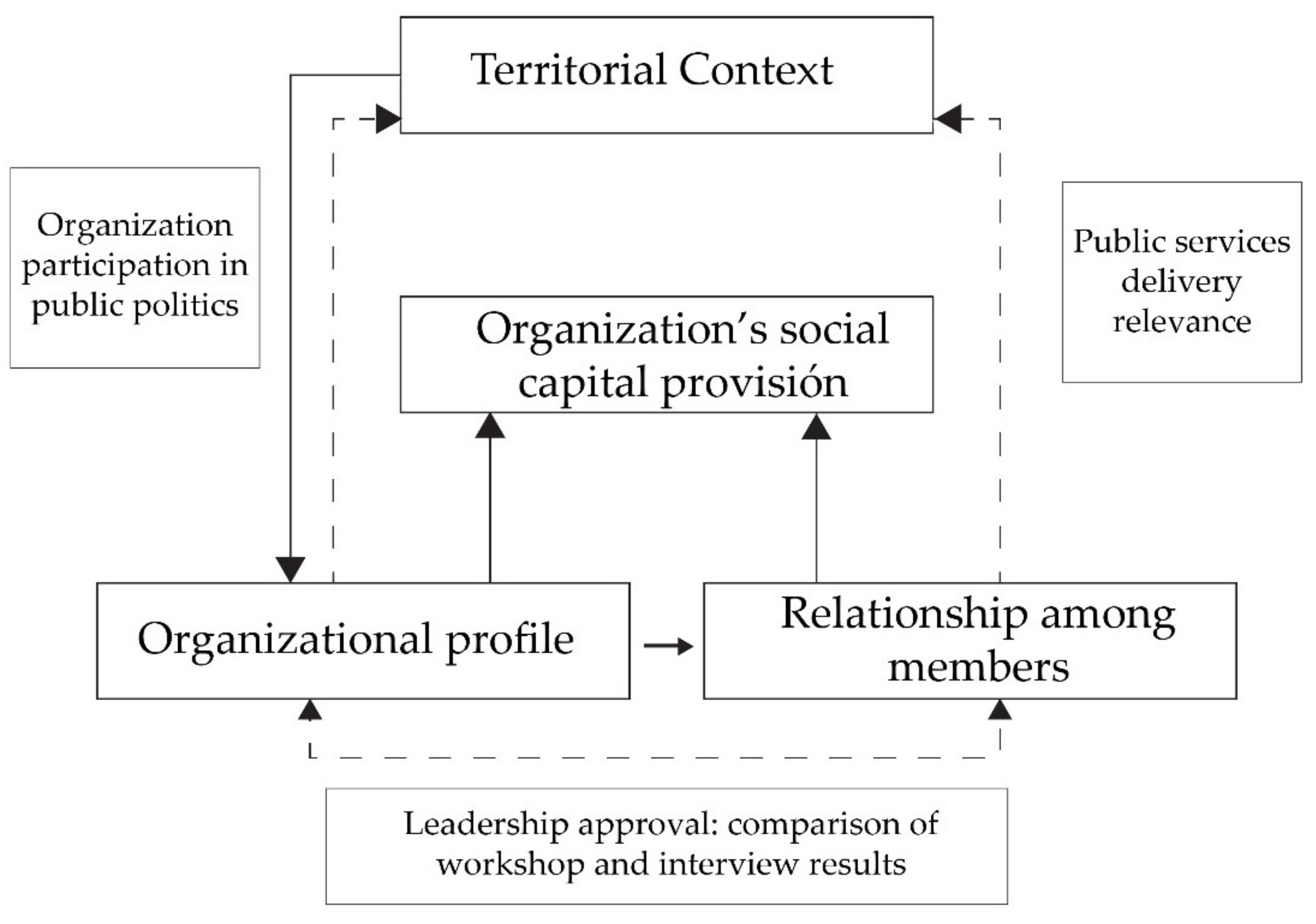

3.2. Results of Integration and the Identification of Social Capital Level in Rural Production Organizations

3.3. Proposed Method for Incorporating the Social Capital of a Rural Production Organization into the Financial Service Delivery Methodology and Risk Qualification

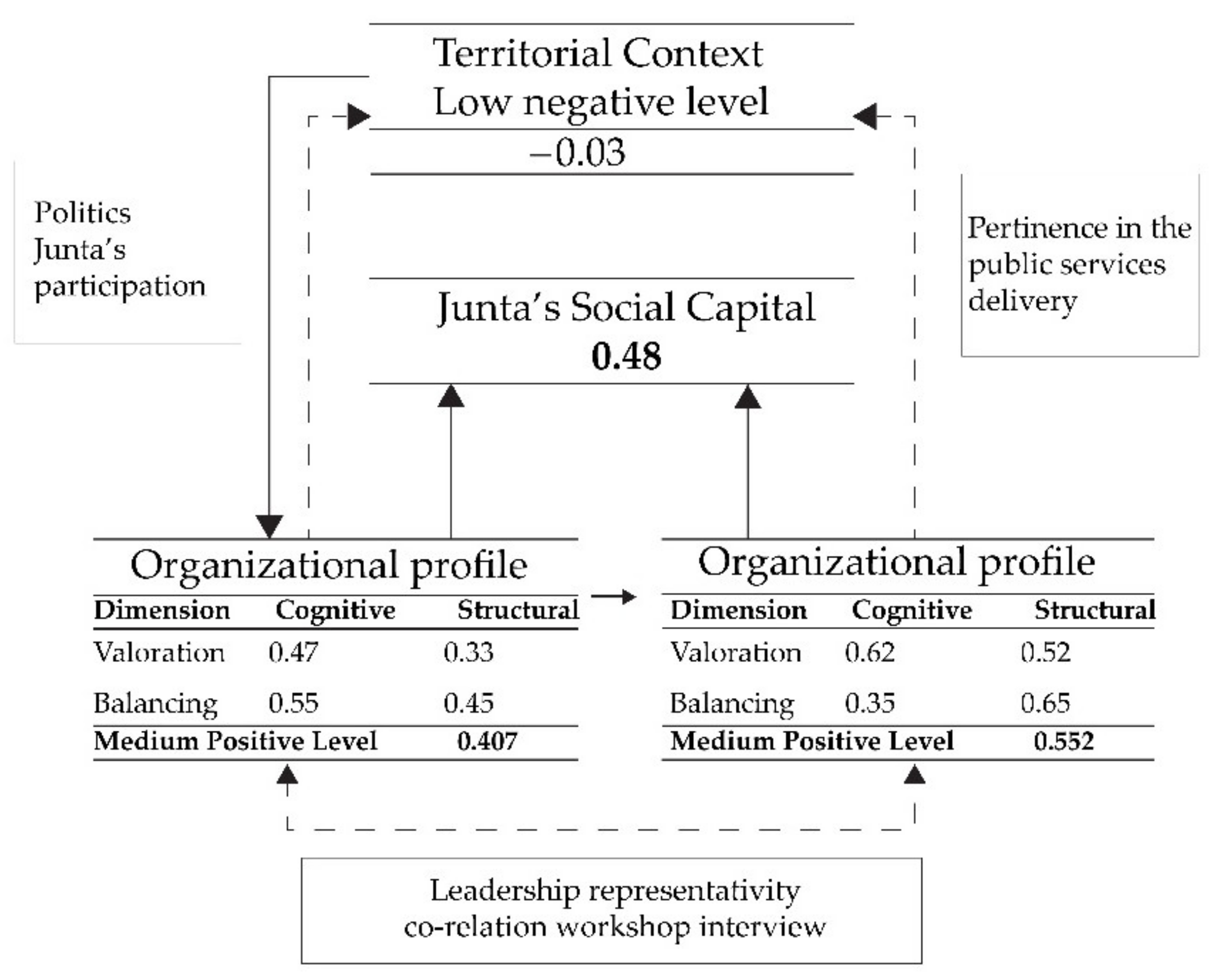

3.4. Case Study Application: The Junta Administradora de Agua Potable y Saneamiento Ambiental Proyecto Nero of Ecuador

4. Final Considerations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arnsperger, C.; Van Parijs, P. Ética Económica y Social: Teorías de la Sociedad Justa; Paidos: Barcelona, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, U. La Sociedad del Riesgo Global; Siglo XXI: Madrid, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Boisier, S. Una (re)visión heterodoxa del desarrollo (territorial): Un imperativo categórico. Estud. Soc. Rev. Aliment. Contemp. Desarro. Reg. 2004, 12, 9–36. [Google Scholar]

- Lebret, L.-J. Dinámica Concreta del Desarrollo; Herder: Barcelona, Spain, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Meier, G.; Seers, D. Pioneros del Desarrollo; Tecnos: Madrid, Spain, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Echeverría, B. Modernidad y Blanquitud; Ediciones Era: México D.F., Mexico, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Maturana, H.R.; Varela, F.J. Autopoiesis and Cognition, Texto Original: The Realization of the Living; Boston Studies in the Philosophy and History of Science; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Searle, J. Actos_de_Habla; Planeta: Barcelona, Spain, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Buciega, A.; Esparcia, J. Desarrollo, Territorio y Capital Social. Un análisis a partir de dinámicas relacionales en el desarrollo rural. REDES Rev. Hisp. Para Análisis Redes Soc. 2013, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Camagni, R. Incertidumbre, Capital Social y Desarrollo Local: Enseñanzas para una gobernabilidad sostenible del territorio. Investig. Reg. 2004, 2, 31–57. [Google Scholar]

- Cornwall, A. The Participation Reader; Zed Books Ltda: London, UK, 2011; Available online: https://www.amazon.es/Participation-Reader-Andrea-Cornwall/dp/1842774026 (accessed on 21 March 2020).

- Jordán, J.; Antuñano, I.; Fuentes, V. Dialnet Métricas–Documento Desarrollo endógeno y política anti-crisis. Rev. de Econ. pública Soc. y Coop. 2013, 78, 245–264. [Google Scholar]

- Shragge, E.; Hanley, J.; Choudry, A. Organize!: Building from the Local for Global Justice; PM Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cámara, N.; Tuesta, D. Measuring Financial Inclusion: A Muldimensional Index. BBVA Res. Work. Pap. 2014, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khandker, S.; Samad, H. Microfinance Growth and Poverty Reduction in Bangladesh: What Does the Longitudinal Data Say? Bangladesh Dev. Stud. 2014, 37, 127–157. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26538550 (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- Roa, M. Inclusión financiera en América Latina y el Caribe: Acceso, uso y calidad. Boletín CEMLA 2013, 59, 121–148. [Google Scholar]

- Bateman, M.; Duvendack, M.; Loubere, N. Is fin-tech the new panacea for poverty alleviation and local development? Contesting Suri and Jack’s M-Pesa findings published in Science. Rev. Afr. Political Econ. 2019, 46, 480–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, D. Life and debt: A view from the south. Econ. Soc. 2021, 50, 36–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavinas, L. The Collateralization of Social Policy under Financialized Capitalism. Dev. Chang. 2018, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mader, P. Rise and Fall of Microfinance in India: The Andhra Pradesh Crisis in Perspective. Strateg. Chang. 2013, 22, 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Soederberg, S. The US Debtfare State and the Credit Card Industry: Forging Spaces of Dispossession. Antipode 2013, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guízar, I.; González-Vega, C.; Miranda, M. Un análisis numérico de inclusión financiera y pobreza. EconoQuantum 2015, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, M.; Aparicio, C.; Cevallos, B. ¿Qué Factores Explican las Diferencias en el Acceso al Sistema Financiero?: Evidencia a Nivel de Hogares en el Perú. Portal FinDev. 2013. Available online: https://www.sbs.gob.pe/Portals/4/jer/pub-estudios-investigaciones/DT_03_2013.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2020).

- Rosado, J.; Villarreal, F.; Stezano, F. Fortalecimiento de la Inclusión y Capacidades Financieras en el Ámbito Rural: Pautas Para un Plan de Acción. CEPAL Documentos de Proyectos, Mayo. 2020. Available online: https://repositorio.cepal.org//handle/11362/45115 (accessed on 8 April 2020).

- Cull, R.; Ehrbeck, T.; Holle, N. La Inclusión Financiera y el Desarrollo: Pruebas Recientes de su Impacto; CGAP: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchis, J.R. La revolución de las finanzas éticas y solidarias. Oikonomics Rev. Econ. Empresa Soc. 2016, 6, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guérin, I. La Microfinance et ses Dérives. Emanciper, Discipliner ou Exploiter? Demopolis: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Armendáriz, B.; Morduch, J. Economía de las Microfinanzas; Fondo de Cultura Económica: México D.F., Mexico, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, U.; Beck-Gernsheim, E. La Individualización. El Individualismo Institucionalizado y Sus Consecuencias Sociales y Políticas; Paidos Iberica: Barcelona, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Issues in the Measurement of Poverty. In Measurement in Public Choice; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Alba, L. Perfil de riesgo en estudiantes de Medicina de la Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. Univ. Médica 2009, 50, 143–155. [Google Scholar]

- Echemendía, B. Definiciones acerca del riesgo y sus implicaciones. Rev. Cuba. de Hig. y Epidemiol. 2010, 49, 470–481. [Google Scholar]

- Saavedra, M.L.; Saavedra, M.J. Modelos para medir el riesgo de crédito de la banca. Cuad. Adm. 2010, 23, 295–319. [Google Scholar]

- Guiso, L.; Sapienza, P.; Zingales, L. The Role of Social Capital in Financial Development. Am. Econ. Rev. 2004, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bebbington, A. (Ed.) Social Conflict, Economic Development and Extractive Industry. Evidence from South America; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, S. Capital social, cultura organizacional, cultura innovadora y su incidencia en las Organizaciones Productivas Rurales Colaborativas. Econ. Soc. 2016, 20, 119–136. [Google Scholar]

- Atiencie, G.Á. Sostenibilidad de organizaciones agroecológicas que apoyan al fomento de la economía popular y solidaria en la provincia del Azuay. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2019. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/tesis?codigo=248659 (accessed on 9 May 2021).

- Block, D. Revisando el constructo de ‘identidad’ en Lingüística Aplicada: Antecedentes, bases, aclaraciones conceptuales e interseccionalidad. In Lenguaje y Construcción de la Identidad: Una Mirada Desde Diferentes Ámbitos; Pfleger, S., Ed.; Universidad Autónoma de México: México D.F., Mexico, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Esman, M.; Uphoff, N. Local Organisations: Intermediaries in Rural Development; Cornell University Press: Cornell, WI, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, M.; Rello, F. Capital Social Rural: Experiencias de México y Centroamérica; UNAM: México D.F., Mexico, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Zepeda, E.; Leos, J.; Carvallo, F. Capital social y mercados financieros crediticios: Demanda de crédito en México, 2010. Probl. del Desarro. 2016, 47, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rodriguez, P.; De la Torre Garcia, R.; Closing the Gap: The Link between Social Capital and Microfinance Services. MPRA Paper. University Library of Munich. 2009. Available online: https://econpapers.repec.org/paper/pramprapa/22974.htm (accessed on 25 February 2020).

- Wilkis, A. Sociología del crédito y economía de las clases populares. Rev. Mex. de Sociol. 2014, 76, 225–252. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E.; Ahn, T.K. Una perspectiva del capital social desde las ciencias sociales: Capital social y acción colectiva. Rev. Mex. de Sociol. 2003, 65, 155–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portes, A. Social capital: Its origins and applications in modern sociology. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1998, 24, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burt, R. The Network Structure of Social Capital. Res. Organ. Behav. 2000, 22, 345–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyx, J.; Bullen, P. Measuring Social Capital in Five Communities. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2000, 36, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N.; Fu, Y.C.; Hsung, R.M. The Position Generator: Measurement Techniques for Investigations of Social Capital. In Social Capital Theory and Research; Routledge: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Gaag, M.; Snijders, T. The Resource Generator: Social Capital Quantification with Concrete Items. Soc. Netw. 2005, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Putnam, R.D. Tuning in, Tuning out: The Strange Disappearance of Social Capital in America. PS Political Sci. Politics 1995, 28, 664–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuyama, F. El Capital Social y La Economía Mundial. Política Exter. 1995, 9. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20643850?seq=1 (accessed on 2 May 2019).

- Zamalvide, J.M. El concepto de capital social y sus estrategias de medición. In Capital Social: Enfoques Alternativos; Anthropos: Barcelona, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cloter, P. La Inclusión Financiera en América Latina. In Inclusión Financiera de Pequeños Productores Rurales; Libros de la CEPAL: Santiago, Chile, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Uphoff, N. Understanding Social Capital: Learnign from the Analysis and Experiencie of Participation. In Social Capital: A Multifaceted Perspective; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- IFAD. Organizaciones de Productores. Available online: https://www.ifad.org/es/farmer-organizations (accessed on 2 May 2019).

- Ayala, J. Instituciones y Economía. Una Introducción al neoinstitucionalismo Económico; Fondo de Cultura Económica: México D.F., Mexico, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Uphoff, N.; Wijayaratna, C.M. Demonstrated Benefits from Social Capital: The Productivity of Farmer Organizations in Gal Oya, Sri Lanka. World Dev. 2000, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, S.; Field, J.; Schuller, T. Social Capital: Critical Perspectives; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Durston, J. El Capital Social Campesino en la Gestión del Desarrollo Rural: Díadas, Equipos, Puentes y Escaleras; CEPAL: Santiago, Chile, 2002; Available online: https://repositorio.cepal.org//handle/11362/2346 (accessed on 21 April 2020).

- Harriss, J. Depoliticizing Development; Anthem Press: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Shortall, S. Point De Vue:Time to Re-Think Rural Development? EuroChoices 2004, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portes, A.; Landolt, P. The Downside of Social Capital. 1996. Available online: https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/handle/10919/67453 (accessed on 6 April 2020).

- Bollier, D. El Ascenso del Paradigma de Los Bienes Comunes; Instituto de Altos Estudios Nacionales del Ecuador: Quito, Ecuador, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Woolcock, M.; Narayan, D. Capital social: Implicaciones para la teoría, la investigación y las políticas sobre desarrollo. World Bank Res. Obs. 2000, 15, 225–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ostrom, E. Trabajar juntos: Acción colectiva, bienes comunes y múltiples métodos en la práctica. UNAM-Centro de Investigaciones Interdisciplinarias en Ciencias y Humanidades/UNAM-Centro Regional de Investigaciones Multidisciplinarias/UNAM-Facultad de Ciencias Políticas y Sociales/UNAM-Facultad de Economía/UNAM-Instituto de Investigaciones Económicas/UNAM-Instituto de Investigaciones Sociales/UNAM-Programa Universitario del Medio Ambiente/Asociación Internacional para el Estudio de los Recursos Comunes/Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas/Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y el Uso de la Biodiversidad/Nacional Financiera/Consejo Civil Mexicano para la Silvicultura Sostenible, A. C./El Colegio de San Luis, A. C./Fondo de Cultura Económica/Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana. 2012. Available online: http://ru.iis.sociales.unam.mx/handle/IIS/4415 (accessed on 18 February 2020).

- Arzaluz, S. La utilización del estudio de caso en el análisis local. Región Soc. 2005, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labayru, C.M.; Gibert, G.J. Examen epistémico de la socio-economía como disciplina intersectada. Polis. Rev. Latinoam. 2017, 47. Available online: http://journals.openedition.org/polis/12538 (accessed on 9 May 2020).

- Burt, R.S.; The Social Capital of Opinion Leaders. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 566. 1999. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1048841 (accessed on 9 May 2021).

- Etzioni, A. A Communitarian Note on Stakeholder Theory 1. Bus. Ethics Q. 1998, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münchhausen, S.; Knickel, K. Rural Development Dynamics: A Comparison of Changes in Rural Web Configurationes in Six European Countries. In Networking the Rural: The Future of Green Regions in Europe; Uitgeverij Van Gorcum: Assen, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Narayan, D. Bonds and Bridges: Social Capital and Poverty. In Social Capital and Economic Development; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rivera, R.; Santos, D.; Fernández, M.; Requero, B.; Cancela, A. Predicción de las actitudes y las intenciones conductuales hacia el emprendimiento social: El papel del liderazgo de servicio en los jóvenes. Int. J. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 33, 664–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Understanding Institutional Diversity; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Przeworski, A.; Teune, H. The Logic of Comparative Inquiry; Wiley_Interscience: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Matas, A. Diseño del formato de escalas tipo Likert: Un estado de la cuestión. Rev. Electrónica de Investig. Educ. 2018, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foladori, H. Dispositivos de intervención institucional. In Métodos Socioanalíticos Para la Gestión y el Cambio en Organizaciones; Editorial Universitaria de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobo-Marín, D. El Acceso al Agua potable Como Derecho Humano y su Regulación en el Régimen Jurídico Mexicano; UNAM: México D.F., Mexico, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dupuits, E. Desde las organizaciones comunitarias del agua hacia el territorio latinoamericano: Espacios transnacionales de convergencia y resistencia. In A Contra Corriente, Agua y Conflictos en América Latina; Abya Yala: Quito, Ecuador, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal, A.; Rivas, L.; Peña, P. Propuesta de un modelo de co-gestión para los Pequeños Abastos Comunitarios de Agua en Colombia. Perf. Latinoam. 2014, 22, 159–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zambrana, T. Clocsas, Antecedentes, Evolución y Potencialidades. Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores y de Cooperación, AECID, Cooperación Española. 2017. Available online: https://www.aecid.es/Centro-Documentacion/Documentos/FCAS/Generales/Clocsas,%20antecedentes,%20evolucion%20y%20potencialidades.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2020).

- Campo-Arias, A.; Oviedo, H. Propiedades Psicométricas de Una Escala: La Consistencia Interna. Rev. de Salud Pública 2008, 10, 831–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bourdieu, P. Las Estructuras Sociales de la Economía; Manantial: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Dirven, M.; Echeverri, R.; Sabalain, C.; Candia Baeza, D.; Faiguenbaum, S.; Rodríguez, A.; Peña, C. Hacia una Nueva Definición de “Rural” con Fines Estadísticos en América Latina. Documentos de Proyectos 397. Naciones Unidas Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL). 2011. Available online: https://econpapers.repec.org/paper/ecrcol022/3858.htm (accessed on 21 March 2020).

- FAO, A. SAGARPA. Marco Conceptual del PESA. Metodología de Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutricional para Agentes de Desarrollo Rural; FAO-UTN: Santiago, Chile, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Denzau, A.; North, D. Shared mental models: Ideologies and institutions. In Elements of Reason; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000; Available online: https://books.google.com/books/about/Elements_of_Reason.html?hl=es&id=oXC40W4HmaIC (accessed on 21 March 2020).

- Evans, P. Government Action, Social Capital and Development: Reviewing the Evidence on Synergy. World Dev. 1996, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Granovetter, M. La fuerza de los lazos débiles. Revisión de la teoría reticular. In Análisis de Redes Sociales: Orígenes, Teorías y Aplicaciones; Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas: Madrid, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Grootaert, C.; Oh, G.T.; Swamy, A. Social Capital, Household Welfare and Poverty in Burkina Faso. J. Afr. Econ. 2002, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R. Capital social: Medición y consecuencias. Rev. Can. de Investig. de Políticas 2001, 2, 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Burt, R. Structural Holes versus Network Closure as Social Capital. In Social Capital: Theory and Research; Routedge: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, J. Social Capital, Human Capital, and Investment in Youth. In Youth Unemployment and Society; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, N. Building a Network Theory of Social Capital’. Connections 1999, 22. Available online: http://faculty.washington.edu/matsueda/courses/590/Readings/Lin%20Network%20Theory%201999.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- Woolcock, M. Social Capital and Economic Development: Toward a Theoretical Synthesis and Policy Framework. Theory Soc. 1998, 27, 151–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucker, L.G. Institutional Theories of Organization. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1987, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uphoff. El capital social y su capacidad de reducción de la pobreza. In Capital Social y Reducción de la Pobreza en América Latina y el Caribe: En Busca de un Nuevo Paradigma; Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe, Universidad del Estado de Michigan: Santiago, Chile, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann, A. Redes y Sistemas de Cooperación; Abya Yala: Quito, Ecuador, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Krugman, P. Vendiendo Prosperidad: Sensatez e Insensatez Económica en una Era de Expectativas Limitadas; Traducido por Esther Rabasco; Ariel: Barcelona, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- SEPS. Actualidad y Cifras de la EPS. Marzo 2021. Superintendencia de Economía Popular y Solidaria. 2021. Available online: https://www.seps.gob.ec/documents/20181/995696/Actualidad+y+Cifras+EPS+%28reducido-ene2021%29.pdf/5087ce15-488f-475a-a5f2-c8bd51d37579 (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- INEC. Proyecciones Poblacionales. 2020. Available online: https://www.ecuadorencifras.gob.ec/institucional/home/ (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Dupuits, E. ¿Una integración latinoamericana a contracorriente?: Redes comunitarias de agua y reproducción de exclusiones culturales y territoriales. In Territorialidades Otras Visiones alternativas de la Tierra y del Territorio Desde el Ecuador; La Tierra: Quito, Ecuador, 2018; Available online: https://repositorio.uasb.edu.ec/bitstream/10644/7211/1/Waldmuller-Altmann-Territorialidades%20otras.pdf#page=110 (accessed on 21 April 2020).

| Field | Measurement Tool | Information Source | Research Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Territorial and operating context | Record of the organization’s territorial and operating context |

|

|

| Organization profile | Organization profile record |

|

|

| Relations among members | Organization members’ relation record |

|

|

| d = [n − (1 − n)] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative Range | Absence of Relation | Positive Range | ||||

| High | Medium | Low | Low | Medium | High | |

| (−1 ≤ d < −0.667) | (−0.667 ≤ d < −0.333) | (−0.333 ≤ d < 0) | 0 | (0 < d ≤ 0.333) | (0.333 < d ≤ 0.667) | (0.667 < d ≤ 1) |

| Social capital territorial context | Level of Social Capital Provision | Dimension Balancing for the Organization Profile | Level of Social Capital Provision | Dimension Balancing for the Relationships Among Members | ||

| Territorial context | Cognitive | Structural | Organization profile | Cognitive | Structural | |

| High positive ( 0.667 < d ≤ 1 ) | 25% | 75% | High positive (0.667 < d ≤ 1) | 25% | 75% | |

| Medium positive (0.333 < d ≤ 0.667) | 35% | 65% | Medium positive (0.333 < d ≤ 0.667) | 35% | 65% | |

| Low positive (0 < d ≤ 0.333) | 45% | 55% | Low positive (0 < d ≤ 0.333) | 45% | 55% | |

| Absence 0 | There is no interaction | Absence 0 | There is no interaction | |||

| Low negative (−0.333 ≤ d < 0) | 55% | 45% | Low negative (−0.333 ≤ d < 0) | 55% | 45% | |

| Medium negative (−0.667 ≤ d < −0.333) | 65% | 35% | Medium negative (−0.667 ≤ d < −0.333) | 65% | 35% | |

| High negative (−1 ≤ d < −0.667) | 75% | 25% | High negative (−1 ≤ d < −0.667) | 75% | 25% | |

| Organization profile’s social capital | Relationship among members’ social capital | |||||

| Social capital average provision of the organization profile and the relationship among members | ||||||

| Social capital provision for the organization | ||||||

| d = [n− (1 − n)] | Social Capital Provision Level | Risk Qualification | Risk Profile | ||

| Positive range | High | (0.667 < d ≤ 1) | High | Low | |

| Medium | Low | ||||

| Low | Low | ||||

| Medium | (0.333 < d ≤ 0.667) | High | Medium | ||

| Medium | Low | ||||

| Low | Low | ||||

| Low | (0 < d ≤ 0.333) | High | High | ||

| Medium | Medium | ||||

| Low | Low | ||||

| Absence of relation | 0 | ||||

| Negative range | High | (−1 ≤ d < −0.667) | Low | Low | |

| Medium | Medium | ||||

| High | High | ||||

| Medium | (−0.667 ≤ d < −0.333) | Low | Low | ||

| Medium | High | ||||

| High | High | ||||

| Low | (−0.333 ≤ d < 0) | Low | High | ||

| Medium | High | ||||

| High | High | ||||

| Analysis Categories | Variable Score | Positive Social Capital (n) | Negative Social Capital (1 − n) | Social Capital Provision | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Field | Dimension | Component | Variable | Variable [n − (1 − n)] | Component | Dimension | Field | |||

| Territorial | −0.03 | |||||||||

| Institutional | −0.03 | |||||||||

| Integrity | −0.39 | |||||||||

| Provision, coverage and quality of public service infrastructures. | 16/30 | 0.53 | 0.47 | 0.06 | ||||||

| Cultural belonging in education and health public services provision. | 1/12 | 0.08 | 0.92 | −0.84 | ||||||

| Synergy | 0.34 | |||||||||

| Junta’s participation in the public politics of local development promotion. | 6/9 | 0.67 | 0.33 | 0.34 | ||||||

| Analysis Categories | Variable Score | Positive Social Capital (n) | Negative Social Capital (1 − n) | Social Capital Provision | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Field | Dimension | Component | Variable | Variable [n − (1 − n)] | Component | Dimension | |||

| Organization profile | Cognitive | 0.467 | |||||||

| Confidence | 0.600 | ||||||||

| Junta’s consolidation | 4/6 | 0.667 | 0.333 | 0.333 | |||||

| Shared experiences | 2/3 | 0.667 | 0.333 | 0.333 | |||||

| Leadership representativity | 13/15 | 0.867 | 0.133 | 0.733 | |||||

| Shared vision | 9/9 | 1.000 | - | 1.000 | |||||

| Reciprocity | 0.333 | ||||||||

| Reciprocity practices | 2/3 | 0.667 | 0.333 | 0.333 | |||||

| Opportunistic behavior punishment | 2/3 | 0.667 | 0.333 | 0.333 | |||||

| Structural | 0.333 | ||||||||

| Roles | 0.667 | ||||||||

| Resources management | 2/3 | 0.667 | 0.333 | 0.333 | |||||

| Internal communication process | 3/3 | 1.000 | - | 1.000 | |||||

| Conflict resolution | 2/3 | 0.667 | 0.333 | 0.333 | |||||

| Decision making | 3/3 | 1.000 | - | 1.000 | |||||

| Rules/norms | 0.667 | ||||||||

| Resources management | 3/3 | 1.000 | - | 1.000 | |||||

| Internal communication process | 2/3 | 0.667 | 0.333 | 0.333 | |||||

| Conflict resolution | 2/3 | 0.667 | 0.333 | 0.333 | |||||

| Decision making | 6/6 | 1.000 | - | 1.000 | |||||

| Procedures | 1.000 | ||||||||

| Resources management | 6/6 | 1.000 | - | 1.000 | |||||

| Nets | −1.000 | ||||||||

| Net density | 0/6 | - | 1.000 | −1.000 | |||||

| Analysis Categories | Variable Score | Positive Social Capital (n) | Negative Social Capital (1 − n) | Social Capital Provision | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Field | Dimension | Component | Variable | Variable [n − (1 − n)] | Component | Dimension | |||

| Relationships among members | Cognitive | 0.620 | |||||||

| Confidence | 0.301 | ||||||||

| Junta’s consolidation | 8/33 | 0.242 | 0.757 | −0.515 | |||||

| Shared experiences | 26/33 | 0.787 | 0.212 | 0.575 | |||||

| Shared vision | 152/165 | 0.921 | 0.078 | 0.842 | |||||

| Reciprocity | 0.939 | ||||||||

| Reciprocity practices | 31/33 | 0.939 | 0.060 | 0.878 | |||||

| Opportunistic behavior punishments | 33/33 | 1.000 | - | 1.000 | |||||

| Structural | 0.515 | ||||||||

| Roles | 0.502 | ||||||||

| Resources management | 148/231 | 0.640 | 0.359 | 0.281 | |||||

| Internal communication process | 27/33 | 0.818 | 0.181 | 0.636 | |||||

| Conflict resolution | 19/33 | 0.575 | 0.424 | 0.151 | |||||

| Decision making | 32/33 | 0.969 | 0.030 | 0.939 | |||||

| Rules/norms | 0.227 | ||||||||

| Resources management | 26/33 | 0.787 | 0.212 | 0.575 | |||||

| Internal communication process | 20/33 | 0.606 | 0.393 | 0.212 | |||||

| Conflict resolution | 12/33 | 0.363 | 0.636 | −0.272 | |||||

| Decision making | 46/66 | 0.696 | 0.303 | 0.393 | |||||

| Procedures | 0.818 | ||||||||

| Resources management | 30/33 | 0.909 | 0.090 | 0.818 | |||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Salinas, J.; Sastre-Merino, S. Social Capital as an Inclusion Tool from a Solidarity Finance Angle. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7067. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137067

Salinas J, Sastre-Merino S. Social Capital as an Inclusion Tool from a Solidarity Finance Angle. Sustainability. 2021; 13(13):7067. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137067

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalinas, Juanita, and Susana Sastre-Merino. 2021. "Social Capital as an Inclusion Tool from a Solidarity Finance Angle" Sustainability 13, no. 13: 7067. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137067

APA StyleSalinas, J., & Sastre-Merino, S. (2021). Social Capital as an Inclusion Tool from a Solidarity Finance Angle. Sustainability, 13(13), 7067. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137067