Site-Specific Determinants and Remains of Medieval City Fortifications as the Potential for Creating Urban Greenery Systems Based on the Example of Historical Towns of the Opole Voivodeship

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Side—Geographical Location, Environmentally Valuable Areas, Heritage Conservation

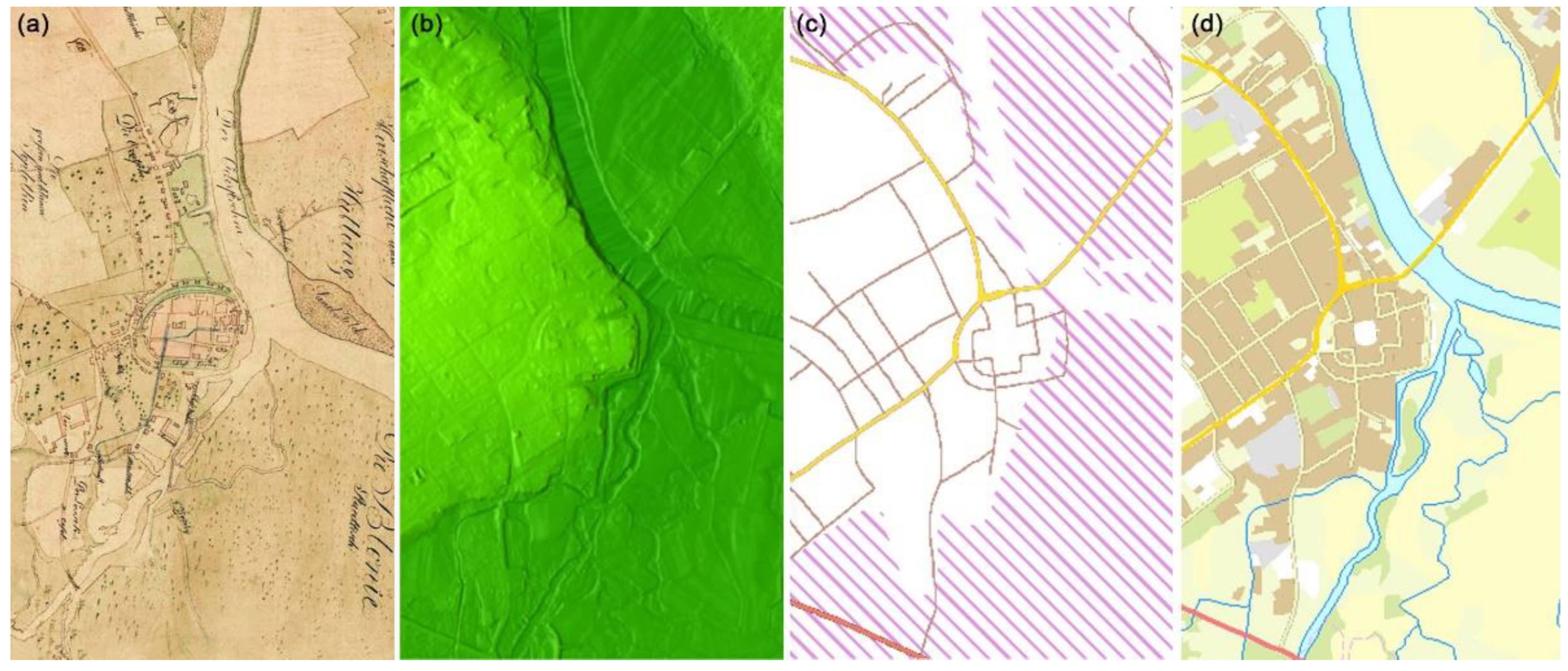

2.2. Methodology

3. Results

3.1. Site-Specific Determinants of Historical Location

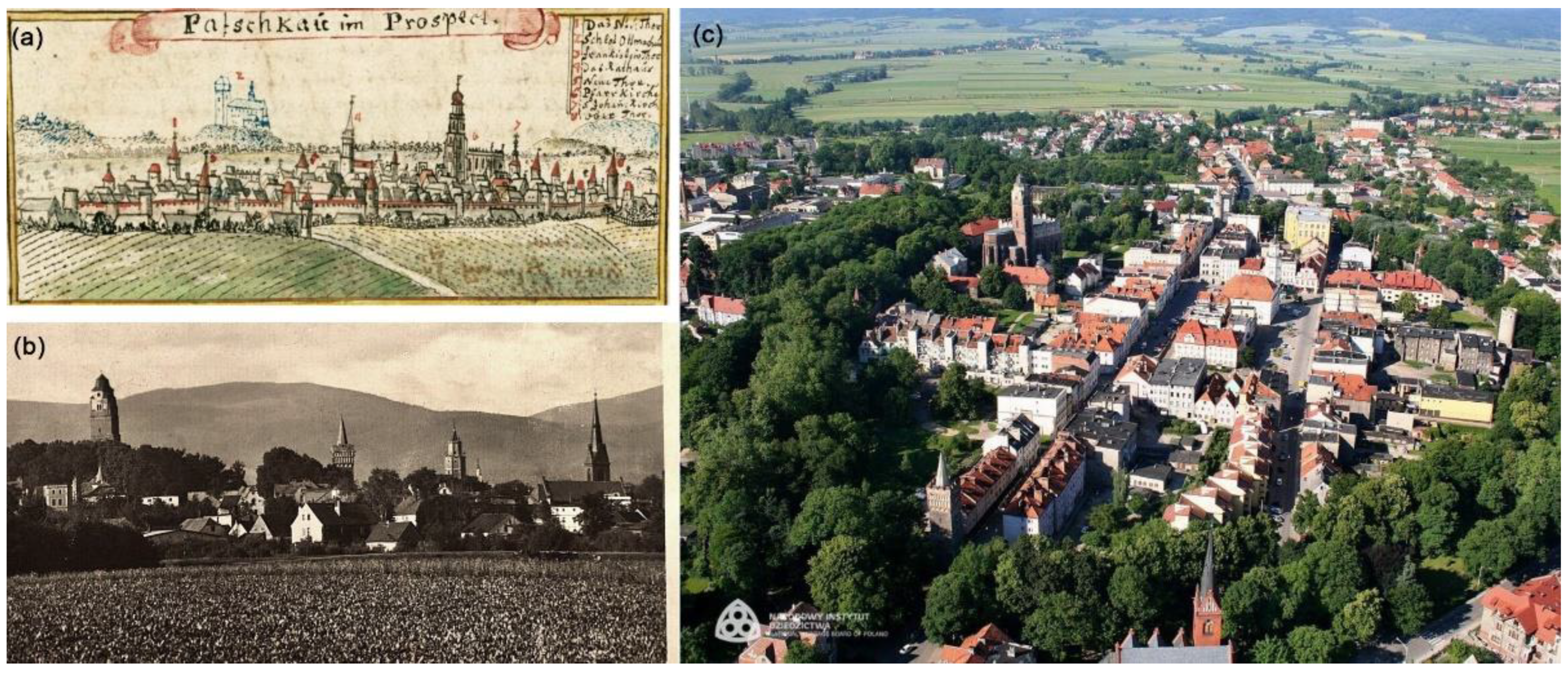

3.2. Historical Heritage of Towns—Urban Layout, Architecture, Skylines

3.3. Contemporary Towns and Cities—Development Directions

3.4. Contemporary Town and Cities—State of Preservation of Urban Layouts, Fortifications, and Skylines

- a varied state of ownership;

- a varied state of preservation;

- a varied state of development;

- fragmentation, gaps in the defensive perimeter;

- lack of archaeological studies;

- landscaped accompanying greenery, in the form of typical city gardens and parks of low visual and functional quality;

- decisions to establish a green area not backed by a functional need in adjacent areas, made randomly and only to follow a general tendency;

- tall trees obscured walls (landscaped greenery);

- natural succession, which caused walls to be obscured from further observation points, erasure of skylines;

- low attractiveness and quality of nearby buildings—an element ignored in conservation and restoration (Figure 5).

3.5. Greenery in the Towns

3.6. Cultural Landscape Potential

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Environmentally valuable, diverse areas around towns;

- Retained development trajectories—as determinants of preserving the traditional landscape;

- Preserved and legible urban layouts;

- Entirely or partially preserved medieval city fortifications;

- Preserved historical skyline composition;

- Diverse landscaped and semi-natural greenery in the town’s structure.

- Investigation: historical and urban research, visibility and exposition analyses, archaeological research, geological and soil morphology testing,

- Design: it should expose the monument, highlight its form, and enhance its values via a visual effect and new accompanying functions, new technical infrastructure in a form that does not compete with the monument. It is essential to adapt the site to persons from different age groups and persons with disabilities, while ensuring night-time use and exposition. Greenery should also mask technical elements and those of poor aesthetic quality; it can also restrict access while not visually interfering with the monument.

- Maintenance (as well as existing structures): maintenance and plant replacement programme, ongoing tree, bush and lawn maintenance, seasonal plant planting plan; reducing the effects of destruction by biotic entities, and the effects of natural succession.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Raport o Stanie Zachowania Zabytków Nieruchomych w Polsce, Zabytki Wpisane do Rejestru Zabytków (Księgi Rejestru A i C); Narodowy Instytut Dziedzictwa: Warszawa, Poland, 2017; Available online: https://nid.pl/pl/Wydawnictwa/inne%20wydawnictwa/RAPORT%20O%20STANIE%20ZACHOWANIA%20ZABYTK%C3%93W%20NIERUCHOMYCH.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- Szmygin, B. Teoria i kryteria wartościowania dziedzictwa jako podstawa jego ochrony. J. Herit. Conserv. 2015, 43, 44–52. [Google Scholar]

- Szmygin, B. (Ed.) Wartościowanie Zabytków Architektury; Polski Komitet Narodowy ICOMOS, Muzeum Pałac w Wilanowie; Muzeum Pałac w Wilanowie: Warszawa, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jarocka, A. (Ed.) Heritage Value Assessment Systems—The Problems and the Current State of Research; Lublin University of Technology; Polish National Committee of the International Council on Monuments and Sites ICOMOS: Lublin–Warsaw, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hodor, K. Zieleń i ogrody w krajobrazach miast. Tech. Trans. Archit. 2012, 6, 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Zachariasz, A. Zieleń Jako Współczesny Czynnik Miastotwórczy ze Szczególnym Uwzględnieniem Roli Parków Publicznych; Wydawnictwo Politechniki Krakowskiej: Kraków, Poland, 2006; Volume 103, pp. 28–29. [Google Scholar]

- Ignatieva, M.; Stewart, G.H.; Meurk, C. Planning and design of ecological networks in urban areas. Landsc. Ecol. Eng. 2011, 7, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozmarynowska, K. Ogrody Odchodzące…? Z Dziejów Gdańskiej Zieleni Publicznej 1708–1945; Słowo/Obraz Terytoria: Gdańsk, Poland, 2011; pp. 94–97. [Google Scholar]

- Forman, R.T.T. Some general principles of landscape and regional ecology. Landsc. Ecol. 1995, 10, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, E.A. Landscape structure indices for assessing urban ecological networks. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2002, 58, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ružička, M.; Mišovičová, R. The general and special principles in landscape ecology. Ekológia 2009, 28, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, H.; Neubert, M.; Marrs, C. (Eds.) Green Infrastucture Handbook—Conceptual and Theoretical Background, Terms and Definition; Technische Universität Dresden: Dresden, Germany, 2019; Available online: https://www.interreg-central.eu/Content.Node/MaGICLandscapes-Green-Infrastructure-Handbook.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- Kieß, W. Urbanismus im Industriezeitalter. Von der Klassizistischen Stadt zur Garden City; Erst & Son: Berlin, Germany, 1991; pp. 200–205. [Google Scholar]

- Bińkowska, I. Natura i Miasto. Publiczna Zieleń Miejska we Wrocławiu od Schyłku XVIII do Początku XX Wieku; Muzeum Architektury, Wydawnictwo Via Nova: Wrocław, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zachariasz, A. Zielony Kraków Dla Przyjemności I Pożytku Szanownej Publiczności; Wydawnictwo Politechniki Krakowskiej: Kraków, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanowski, J. Architektura Obronna w Krajobrazie Polski. Od Biskupina do Westerplatte; PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Wielgus, K.; Środulska-Wilelgus, J.; Staniewska, A. Krajobraz Warowny Polski: Procesy Rewaloryzacji i Percepcji: Próba Syntezy; Wydawnictwo Politechniki Krakowskiej: Kraków, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Von Rohrscheidt, A.M. Wykorzystanie średniowiecznych obiektów obronnych w Polsce w ramach różnych form turystyki kulturowej. Tur. Kult. 2010, 6, 4–25. [Google Scholar]

- Środulska-Wilelgus, J. Rola Turystyki Kulturowej w Ochronie i Udostępnieniu Krajobrazu Warownego; Wydawnictwo Politechniki Krakowskiej: Kraków, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Adamska, M.E. Zabytkowe planty miejskie w Brzegu. Przestrz. Urban. Archit. 2015, 1, 45–58. Available online: https://www.ejournals.eu/PUA/2015/Volume-1/art/9542/ (accessed on 21 May 2021).

- Adamska, W.E. The historic city parks of Opole Silesia. Tech. Trans. Archit. 2014, 5-A, 237–254. [Google Scholar]

- Kimic, K. The location and role of old walls as green belts in shaping the landscape of towns in the 19th century. Tech. Trans. Archit. 2016, 1, 143–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodor, K.; Fekete, A.; Matusik, A. The future of Planty Park in Cracow compared to other examples of city walls being transformed into urban parks. In Proceedings of the ECLAS Conference, Ghent, Belgium, 9–12 September 2018; Delarue, S., Dufour, R., Eds.; University College Ghent—School of Arts—Landscape & Garden Architecture and Landscape Development: Ghent, Belgium, 2018; pp. 411–416. [Google Scholar]

- Bimler, K. Die Schlesischen Massiven Wehrbauten, Bd. 1–5; Komission Heydebrand-Verlag: Breslau, Poland, 1940–1944. [Google Scholar]

- Przyłęcki, M. Budowle i Zespoły Obronne na Śląsku; Towarzystwo Opieki nad Zabytkami: Warszawa, Poland, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Thullie, C. Zabytki Architektoniczne Ziemi Śląskiej na tle Rozwoju Architektury w Polsce; Wydawnictwo “Śląsk”: Katowice, Poland, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Chrzanowski, T.; Kornecki, M. Sztuka Śląska Opolskiego, od Średniowiecza do Końca w. XIX; Wydawnictwo Literackie: Kraków, Poland, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Adamska, M.E. Transformacie Rynków Średniowiecznych Miast Śląska Opolskiego od XIII Wieku do Czasów Współczesnych. Przerwane Tradycje, Zachowane Dziedzictwo, Nowe Narracje; Politechnika Opolska: Opole, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Piechaczek, B. Średniowieczne Kamienne Obwarowania Miast Opolszczyzny do Końca XV Wieku. Ph.D. Thesis, Katolicki Uniwersytet Lubelski Jana Pawła II, Lublin, Poland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Przybyłok, A. Mury Miejskie na Górnym Śląsku w Późnym Średniowieczu. Ph.D. Thesis, Uniwersytet Łódzki, Łódź, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Legendziewicz, A. Selected city gates in Silesia—Research issues. Technol. Trans. 2019, 3, 71–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Legendziewicz, A. Brama Grobnicka (zwana Klasztorną) w Głubczycach w świetle badań architektonicznych i ikonograficznych. In Opolski Informator Konserwatorski 2015; Wojewódzki Urząd Ochrony Zabytków w Opolu: Opole, Poland, 2015; pp. 103–112. [Google Scholar]

- Legendziewicz, A. Architektura bram miejskich Głogówka od XIV do XX wieku. Kwart. Opol. 2018, 4, 105–120. [Google Scholar]

- Legendziewicz, A. Mury miejskie Kluczborka—od średniowiecza do współczesności. In Opolski Informator Konserwatorski 2015; Wojewódzki Urząd Ochrony Zabytków w Opolu: Opole, Poland, 2015; pp. 113–121. [Google Scholar]

- Legendziewicz, A. Badania architektury Grodkowa. Średniowieczne fortyfikacje miejskie. In Z dziejów Grodkowa i ziemi grodkowskiej, p. 2; Urząd Miejski w Grodkowie: Grodków, Poland, 2015; pp. 67–88. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkaniec, A.; Wichrowski, M. (Eds.) Fortyfikacje w Przestrzeni Miasta; Uniwersytet Przyrodniczy w Poznaniu: Poznań, Poland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Przyłęcki, M. Miejskie Fortyfikacje Średniowieczne na Dolnym Śląsku. Ochrona, Konserwacja, Ekspozycja 1850–1980; PP PKŻ: Warszawa, Poland, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Adamska, M.E. Średniowieczne układy urbanistyczne miast Śląska Opolskiego—Stan zachowania i rewitalizacja. Przegląd Bud. 2013, 3, 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Series of Publications Issued by PKN ICOMOS. Available online: http://www.icomos-poland.org/pl/publikacje.html (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Górski, A. (Ed.) Obwarowania miast. Problematyka ochrony, konserwacji, adaptacji i ekspozycji. In Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference, Kożuchów, Poland, 28–30 April 2010; Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Ziemi Kożuchowskiej: Kożuchów, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Transnational Model of Sustainable Protection and Conversation of Historic Ruins: Best Practices Handbook; Lublin University Of Technology: Lublin, Poland, 2020.

- Cydzik, J. Przebudowa zabytkowego ośrodka staromiejskiego na przykładzie miasta Paczkowa. Ochr. Zabytk. 1961, 14, 75–92. [Google Scholar]

- Steinborn, B. Otmuchów i Paczków; Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich: Wrocław, Poland, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Dziewulski, W.; Hawranek, F. Opole Monografia Miasta; Instytut Śląski w Opolu: Opole, Poland, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Eysmonty, R.; Goliński, M. (Eds.) Namysłów. In Atlas Historycznych Miast Polskich, t IV, Śląsk, Zeszyt 11; Instytut Archeologii i Etnologii PAN: Wrocław, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Borkowski, M.; Czapliński, M.P. Biała—Historia i Współczesność; Instytut Śląski: Opole-Biała, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Meisner, J. (Ed.) Byczyny Przeszłość i Dzień Dzisiejszy; Instytut Śląski w Opolu: Opole, Poland, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Chrzanowski, T. Głogówek; Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich: Wrocław, Poland, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Adamska, M. Rewaloryzacja starego miasta w Głubczycach. Zesz. Nauk. Politech. Opol. Ser. Bud. 1998, 43, 132–149. [Google Scholar]

- Cimała, B. Kluczbork-Dzieje Miasta; Instytut Śląski w Opolu: Opole, Poland, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Chrząszcz, J. Historia Miasta Krapkowice na Górnym Śląsku od 1914; Sady: Krapkowice, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Heffner, K. Ujazd—historia i Współczesność; Instytut Śląski w Opolu: Opole, Poland, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Inwentarz Zespołu PP PKZ Oddział Wrocław, Zespół Pracowni Dokumentacji Naukowo-Historycznej PP PKZ. Available online: https://www.nid.pl/pl/Regiony/Dolnoslaskie/Wykaz%20dokumentacji/01_PP%20PKZ%20Wroc%C5%82aw%20Pracownia%20Dokumentacji%20Naukowo-Historycznej.pdf (accessed on 8 June 2021).

- Dziennik Ustaw, Poz. 1240, Rozporządzenie Prezydenta Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej z Dnia 22 Października 2012 r. w Sprawie Uznania za Pomnik Historii Paczków—Zespół Staromiejski ze Średniowiecznym Systemem Fortyfikacji. Available online: https://nid.pl/pl/Informacje_ogolne/Zabytki_w_Polsce/Pomniki_historii/Lista_miejsc/Paczk%C3%B3w_rozporz%C4%85dzeenie.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2020).

- Pudełko, J. Zagadnienia Wielkości Powierzchni Średniowiecznych Miast Śląskich; Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich: Wrocław, Poland, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Eysymontt, R. Kod Genetyczny Miasta. Średniowieczne Miasta Lokacyjne Dolnego Śląska na tle Urbanistyki Europejskiej; Via Nova: Wrocław, Poland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bahlcke, J. Górny Śląsk—studium przypadku powstania: Regionów historycznych, wyobrażeń o obszarach kulturowych, histograficznych koncepcji przestrzeni. In Historia Górnego Śląska. Polityka, Gospodarka i Kultura Europejskiego Region; Bahlcke, J., Gawrecki, D., Kaczmarek, R., Eds.; Dom Współpracy Polsko-Niemieckiej: Gliwice, Poland, 2011; pp. 17–37. [Google Scholar]

- Główny Urząd Statystyczny (GUS)—Central Statistical Office of Poland; Local Data Bank. Available online: https://bdl.stat.gov.pl/BDL/start (accessed on 11 October 2020).

- Raport o Stanie Środowiska Województwa Opolskiego 2020. Główny Inspektorat Ochrony Środowiska, Departament Monitoringu Środowiska, Regionalny Wydział Monitoringu Środowiska w Opolu: Opole, Poland, 2020. Available online: http://www.gios.gov.pl/images/dokumenty/pms/raporty/stan_srodowiska_2020_opolskie.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2021).

- Program Ochrony Środowiska Województwa Opolskiego na Lata 2012–2015 z Perspektywą do Roku 2019. Available online: https://www.opolskie.pl/program-ochrony-srodowiska/ (accessed on 24 January 2021).

- Sustainable Development Report 2020. Available online: https://dashboards.sdgindex.org/rankings (accessed on 24 January 2021).

- Kapera, I. Rozwój Zrównoważony Turystyki. Problemy Przyrodnicze, Społeczne i Gospodarcze na Przykładzie Polski; Oficyna Wydawnicza AFM: Kraków, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bąk, I.; Matlegiewicz, M. Przestrzenne zróżnicowanie atrakcyjności turystycznej w Polsce w 2008 roku. In Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Szczecińskiego. Ekonomiczne Problemy Usług 2010, 52 Potencjał Turystyczny. Zagadnienia Przestrzenne; Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu Szczecińskiego: Szczecin, Poland, 2012; pp. 57–67. [Google Scholar]

- Wiśniewska, A. Ocena rozwoju turystyki zrównoważonej w polskich regionach. Gospodarka w Praktyce i Teorii 2017, 49, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- von Rohscheidt, A.M. Turystyka Kulturowa. Fenomen, Potencjał, Perspektywa, 3rd ed.; GWSHM: Gniezno, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Potocka, I. Atrakcyjność turystyczna i metody jej identyfikacji. In Uwarunkowania i Plany Rozwoju Turystyki, Tom III, Walory i Atrakcje Turystyczne, Potencjał Turystyczny, Plany Rozwoju Turystyki; Młynarczyk, S., Zajajdacz, A., Eds.; Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu im. Adama Mickiewicza w Poznaniu: Poznań, Poland, 2009; pp. 19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Brezovec, T.; Bruce, D. Tourism Development: Issues for Historic Walled Towns. Management 2009, 4, 101–114. [Google Scholar]

- Tülek, B.; Atik, M. Walled towns as defensive cultural landscapes: A case study of Alanya—A walled town in Turkey. WIT Trans. Environ. 2014, 143, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Analizy Statystyczne. Ochrona Środowiska 2020/Statistical Analyses. Environment 2020; Główny Urząd Statystyczny/Statistics: Warszawa, Poland, 2020. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/srodowisko-energia/srodowisko/ochrona-srodowiska-2020,1,21.html (accessed on 25 January 2021).

- Von Wrede, C.F. Kriegs-Karte von Schlesien, 1747–1753; Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Kartenabteilung, Sygn. 15060; Lengenfelder, H (Verlag): München, Germany, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Wernher, F.B. Silesia in Compendio seu Topographia das ist Praesentatio und Beschreibung des Herzogthums Schlesiens […] Pars I. 1750–1800, BUWr Oddział Rękopisów. Available online: https://www.bibliotekacyfrowa.pl/dlibra/publication/8092/edition/15414 (accessed on 15 October 2020).

- Wernher, F.B. Scenographia Urbium Silesiae, Nürnberg, 1737–1752, BUWr Oddział Rękopisów. Available online: https://bibliotekacyfrowa.pl/publication/3022 (accessed on 15 October 2020).

- Sowińska-Świerkosz, B.N.; Michalik-Śnieżek, M. The Methodology of Landscape Quality (LQ) Indicators Analysis Based on Remote Sensing Data: Polish National Parks Case Study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sowinska-Swierkosz, B.N.; Chmielewski, T.J. A new approach to the identification of Landscape Quality Objectives (LQOs) as a set of indicators. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 184, 596–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myczkowski, Z. Kryteria waloryzacji krajobrazów Polski—propozycja systematyki. In Identyfikacja i Waloryzacja Krajobrazów—Wdrażanie Europejskiej Konwencji Krajobrazowej; Generalna Dyrekcja Ochrony Środowiska: Warszawa, Poland, 2020; pp. 64–73. [Google Scholar]

- Fornal-Pieniak, B.; Żarska, B. Metody waloryzacji krajobrazowej na potrzeby turystyki i rekreacji. Acta Sci. Pol. 2014, 13, 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Czarnecki, W. Planowanie Miast i Osiedli, T.I. Wiadomości Ogólne. Planowanie Przestrzenne; PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Jedwab, R.; Johnson, N.D.; Koyama, M. Medieval cities through the lens of urban economics. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syperka, J. Dzieje gospodarcze Górnego Śląska w średniowieczu. In Historia Górnego Śląska. Polityka, Gospodarka i Kultura Europejskiego Regionu; Bahlcke, J., Gawrecki, D., Kaczmarek, R., Eds.; Dom Współpracy Polsko-Niemieckiej: Gliwice, Poland, 2011; pp. 295–308. [Google Scholar]

- Bogucka, M.; Samsonowicz, H. Dzieje Miast i Mieszczaństwa w Polsce Przedrozbiorowej; Zakład Narodowy Imienia Ossolińskich Wydawnictwo: Wrocław, Poland, 1989; pp. 45–104. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, R. Czeladź. Ze studiów nad budową i kształtem miasta średniowiecznego. Kwart. Arch. Urban. 2010, 55, 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Guzman, P. Assessing the sustainable development of the historic urban landscape through local indicators. Lessons from a Mexican World Heritage City. J. Cult. Herit. 2020, 46, 320–327. [Google Scholar]

- Christopher Tweed, Margaret Sutherland, Built cultural heritage and sustainable urban development. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 83, 62–69. [CrossRef]

- Aminzadeh, B.; Khansefid, M. A case study of urban ecological networks and a sustainablecity: Tehran’s metropolitan area. Urban Ecosyst. 2010, 13, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balestrieri, M.; Ganciu, A. Greenways and Ecological Networks: Concepts, Differences, Similarities. Agric. Res. Technol. 2017, 12, 0011–0013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Środulska-Wielgus, J.; Staniewska, A.; Łakomy, K.; Wielgus, K. The historical elements of Kraków’s green system—protection challenges for landscape planning in the 21st century. In Proceedings of the 5th Fábos Conference on Landscape and Greenway Planning, Budapest, Hungary, 1 July 2016; Jombach, S., Ed.; Szent István University, Department of Landscape Planning and Regional Development: Budapest, Hungary, 2016; pp. 439–446. [Google Scholar]

- Raszeja, E.; Gałecka-Drozda, A. Współczesne interpretacje poznańskiego systemu zieleni w kontekście strategii miasta zrównoważonego. Stud. Miej. 2015, 19, 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Niedźwiecka-Filipiak, I.; Rubaszek, J.; Potyrała, J.; Filipiak, P. The Method of Planning Green Infrastructure System with the Use of Landscape-Functional Units (Method LaFU) and its Implementation in the Wrocław Functional Area (Poland). Sustainability 2019, 11, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xing, Y.; Brimblecombe, P. Traffic-derived noise, air pollution and urban park design. J. Urban Des. 2020, 25, 590–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Jiang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Zhu, L. Sustainability of Historical Heritage: The Conservation of the Xi’an City Wall. Sustainability 2019, 11, 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Karta Ochrony Historycznych Ruin Przyjęta Uchwałą Walnego Zgromadzenia Członków PKN ICOMOS w Dniu 4 Grudnia 2012 r. Available online: http://www.icomos-poland.org/pl/dokumenty/uchwaly/130-karta-ochrony-historycznych-ruin.html (accessed on 29 January 2021).

- Trochonowicz, M. Obiekty murowe w ruinie. Wpływ czynników degradujących na ich zachowanie. In Ochrona, Konserwacja i Adaptacja Zabytkowych Murów: Trwała Ruina II: Problemy Utrzymania i Adaptacji; Szmygin, B., Ed.; Lubelskie Towarzystwo Naukowe, Polski Komitet Narodowy ICOMOS; Politechnika Lubelska: Lublin, Poland, 2010; pp. 172–184. [Google Scholar]

- Trochonowicz, M.; Klimek, B.; Lisiecki, D. Biological corrosion and vegetation in the aspect of permanent ruin. Bud. Archit. 2018, 17, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Report on Current State-of-Art of Use and Re-Use of Medieval Ruins; Interreg Central Europa, Version 2, 12/2017. Available online: https://www.interreg-central.eu/Content.Node/RUINS/D.T2.1.1---Report-on-the-current-state-of-art-on-contempo-1-pdf (accessed on 10 February 2021).

- Ashworth, G.J.; Bruce, D.M. Town Walls, Walled Towns and Tourism: Paradoxes and paradigms. J. Herit. Tour. 2009, 4, 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 21 May 2020).

- Walter, G.R. Economics, Ecology-Based Communities, and Sustainability. Ecol. Econ. 2002, 42, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampton, M.P. Heritage, local communities and economic development. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 735–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total Number of Towns in the Opole Voivodeship | Towns of Medieval Origins | Silesian Town with a Central, Quadrate Market Square | Town Charters Issued in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries | Towns with Documented Medieval City Fortifications | Medieval Fortifications Absorbed by Modern Ones | Towns Subjected to Detailed Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 36 | 29 | 25 | 25 | 18 | 3 | 15 |

| a. Indicator | b. Historical Significance | c. Contemporary Significance | d. Value | e. Investigation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental site-specific determinants | Impact on site-specific determinants | Environmental and landscape assets | Diversity |

|

| Urban layout | Socio-legal, organisational, functional structure | Fundamental characteristic of a layout | Legibility of urban layout and structure |

|

| City morphology (development directions) | Socio-economic development | Determinant of traditional landscape retention | Continuity of the traditional development model |

|

| City fortifications | Defensibility, exposition | Elements of identity, exposition | State of preservation |

|

| Panoramas (skyline composition) | Informative symbol, spatial orientation, a sign of status and wealth | Landscape asset | Quality and state of preservation—legibility of historical skyline composition |

|

| Terrain | Defensibility | Hills, Slopes |

|---|---|---|

| Exposition | ||

| Waterways | Transport | River routes, crossings |

| Economy | Commerce Fishing Others (e.g., mills) | |

| Defensibility | River bed Wetlands, floodlands | |

| Exposition | Vista foregrounds of river valleys and wetlands |

| Town charter issuance | Biała 1225, Byczyna 1268, Głogówek 1275, Głubczyce przed 1253, Głuchołazy 1225, Grodków 1278, Kluczbork 1253, Krapkowice 1284, Opole 1217, Namysłów via 1270, Otmuchów via 1347, Paczków via 1254, Prudnik 1279, Strzelce Op., 1290, Ujazd 1223 |

| Plan | Oval plan (boat/pseudo-oval shape, ‘dwarf city’), enclosed, grid-based, rectangular layout, with a geometricised main square (Ring, Circus) in the centre, surrounded by fortifications on an oval-like plan. Layouts both regular and distorted by local conditions |

| Major composition elements | Module, axis -> market square, parcel, streets |

| Functional buildings | Fortifications, town hall, church, monastery, hospital, castle, others (synagogues) |

| Fortifications | Moats, embankments, walls—made of stone (curtain wall), 1.5–2.5 m thick, height without breastwork at 4.5–8.4 m), towers, gates. |

| Main identification (skyline) elements | City walls, towers, church, castle |

| Period of Construction, Century | Approximate Wall Circumference | Surviving Sections [%] | Gatehaus | Tower | Turret | Listed Site | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Biała | Fifteenth | 1100 | M | - | 1 | yes | yes |

| 2 | Byczyna | Fifteenth–sixteenth | 1000 | L | 3 | 1 | yes | yes |

| 3 | Głogówek | Fourteenth–fifteenth | 1350 | M | 1 | 1 | yes | yes |

| 4 | Głubczyce | Thirteenth, fourteenth–fifteenth | 1500 | M | - | - | yes | yes |

| 5 | Głuchołazy | Fourteenth, fifteenth | 970 | S | - | 1 | - | only a tower |

| 6 | Grodków | Fourteenth, sixteenth | 1270 | M | 2 | 1 | yes | yes |

| 7 | Kluczbork | Fifteenth–sixteenth | 850 (1290) | M | - | 1 | - | yes |

| 8 | Krapkowice | Fourteenth | 850 | M | 1 | - | yes | yes |

| 9 | Namysłów | Fourteenth | 1600 | M | 1 | 2 | yes | yes |

| 10 | Opole | Fourteenth | 1500 | S | - | 1 | yes | yes |

| 11 | Otmuchów | Fourteenth | 1200 | S | - | 1 | no | yes |

| 12 | Paczków | Fourteenth | 1200 | L | 1 | 3 | yes | yes |

| 13 | Prudnik | Fourteenth | 1100 | S | - | 1 | yes | yes |

| 14 | Strzelce Opol. | Fourteenth | 900 | S | - | 1 | yes | yes |

| 15 | Ujazd | Fourteenth | 1100 | N | - | - | - | - |

| Municipal Unit | Rest and Walking Parks [ha] | Urban Gardens [ha] | Street Greenery [ha] | Housing Estate Greenery [ha] | Cemeteries [ha] | Municipal Forests [ha] | Total [ha] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Biała | 0.0 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 0.0 | 4.9 |

| 2 | Byczyna | 6.3 | 7.3 | 0.0 | 19.0 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 34.5 |

| 3 | Głogówek | 16.8 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 19.2 | 2.4 | 12.1 | 51.9 |

| 4 | Głubczyce | 11.3 | 7.2 | 6.8 | 31.3 | 5.6 | 0.0 | 62.2 |

| 5 | Głuchołazy | 0.0 | 4.3 | 0.5 | 20.3 | 8.6 | 178.6 | 212.3 |

| 6 | Grodków | 6.4 | 4.6 | 0.0 | 15.9 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 28.8 |

| 7 | Kluczbork | 70.0 | 4.6 | 4.7 | 107.2 | 7.2 | 128.6 | 322.3 |

| 8 | Krapkowice | 52.6 | 6.3 | 6.5 | 71.8 | 3.0 | 1.6 | 141.8 |

| 9 | Namysłów | 29.2 | 17.2 | 7.7 | 76.1 | 10.3 | 4.8 | 145.3 |

| 10 | Opole | 182.5 | 5.0 | 216.0 | 368.4 | 44.7 | 13.9 | 830.5 |

| 11 | Otmuchów | 0.0 | 8.5 | 0.3 | 8.5 | 3.0 | 109.6 | 129.9 |

| 12 | Paczków | 18.2 | 2.5 | 1.0 | 23.7 | 2.9 | 4.2 | 52.5 |

| 13 | Prudnik | 11.5 | 15.2 | 4.5 | 43.5 | 7.5 | 7.9 | 90.1 |

| 14 | Strzelce Opolskie | 64.6 | 18.0 | 3.3 | 104.3 | 7.6 | 2.3 | 200.1 |

| 15 | Ujazd | 5.4 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 5.8 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 13.1 |

| Municipal Unit | Rv | Cp | Sq | Cm | Al | Pfg | Wl | He | Ot | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Biała | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | 9 |

| 2 | Byczyna | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | 9 |

| 3 | Głogówek | x | x | x | x | x | x | 6 | |||

| 4 | Głubczyce | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | 9 |

| 5 | Głuchołazy | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | 7 | ||

| 6 | Grodków | x | Pfg | x | x | x | x | x | x | 7 | |

| 7 | Kluczbork | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | 7 | ||

| 8 | Krapkowice | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | 9 |

| 9 | Namysłów | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | 8 | |

| 10 | Opole | x | x | x | x | x | 5 | ||||

| 11 | Otmuchów | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | 7 | ||

| 12 | Paczków | x | Pfg | x | x | x | x | x | x | 7 | |

| 13 | Prudnik | x | x | x | x | x | x | 6 | |||

| 14 | Strzelce Opolskie | x | x | x | x | x | x | 6 | |||

| 15 | Ujazd | x | x | x | x | x | x | 6 |

| Environmental Diversity of a Site | Urban Layout Legibility | Retained Development Trajectories | Surviving City Fortifications | Legibility of Skyline Composition | Landscaped Greenery | Individual Qualities and Cultural Landscape Potential | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Biała | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 11 |

| 2 | Byczyna | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 9 |

| 3 | Głogówek | 1 | 2 | 1, except for the east | 1 | 2 | 1 | 8 |

| 4 | Głubczyce | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 6 |

| 5 | Głuchołazy | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| 6 | Grodków | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 8 |

| 7 | Kluczbork | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 6 |

| 8 | Krapkowice | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 10 |

| 9 | Namysłów | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 7 |

| 10 | Opole | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| 11 | Otmuchów | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 10 |

| 12 | Paczków | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 10 |

| 13 | Prudnik | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| 14 | Strzelce Opol. | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| 15 | Ujazd | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Łakomy, K. Site-Specific Determinants and Remains of Medieval City Fortifications as the Potential for Creating Urban Greenery Systems Based on the Example of Historical Towns of the Opole Voivodeship. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7032. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137032

Łakomy K. Site-Specific Determinants and Remains of Medieval City Fortifications as the Potential for Creating Urban Greenery Systems Based on the Example of Historical Towns of the Opole Voivodeship. Sustainability. 2021; 13(13):7032. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137032

Chicago/Turabian StyleŁakomy, Katarzyna. 2021. "Site-Specific Determinants and Remains of Medieval City Fortifications as the Potential for Creating Urban Greenery Systems Based on the Example of Historical Towns of the Opole Voivodeship" Sustainability 13, no. 13: 7032. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137032

APA StyleŁakomy, K. (2021). Site-Specific Determinants and Remains of Medieval City Fortifications as the Potential for Creating Urban Greenery Systems Based on the Example of Historical Towns of the Opole Voivodeship. Sustainability, 13(13), 7032. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137032