Setting Thresholds to Define Indifferences and Preferences in PROMETHEE for Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment of European Hydrogen Production

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment—Indicators and Uncertainties

2.1.1. Indicators

2.1.2. Uncertainties

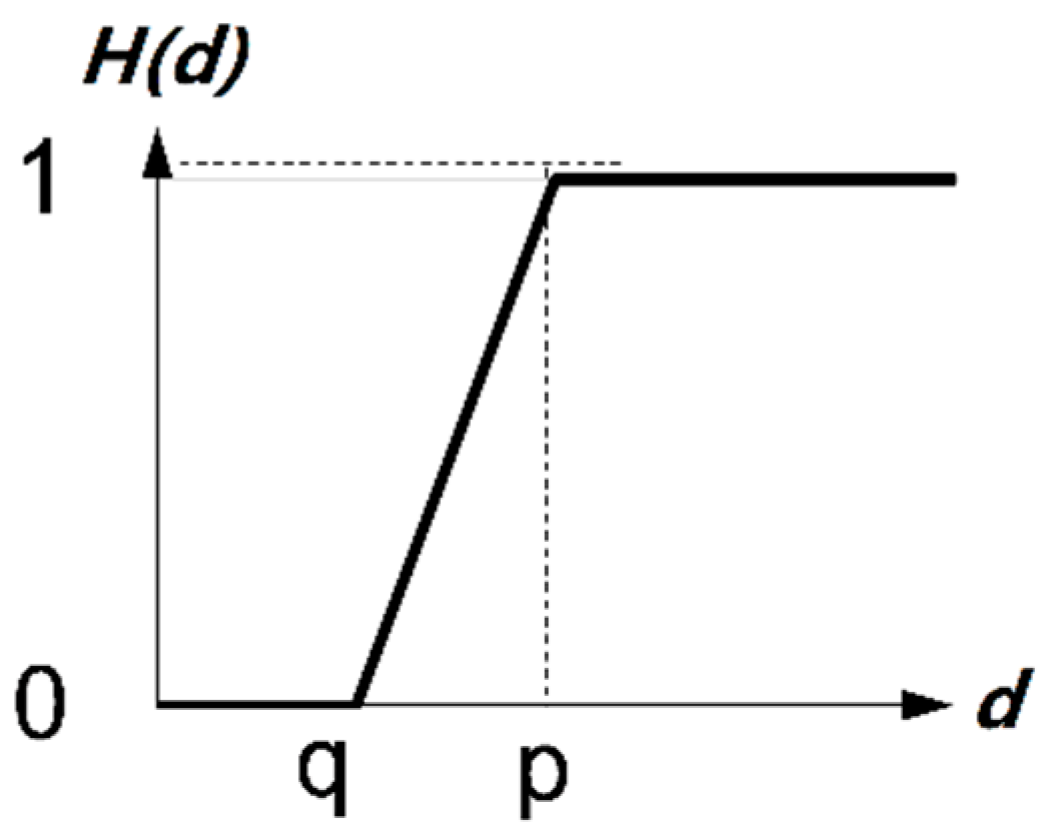

2.2. Outranking

- Determination of deviations based on pairwise comparisons between different options.

- Application of the preference function.

- Calculation of the global preference index.

- Calculation of positive and negative outranking flows for each alternative.

- Net outranking flow for each alternative and complete ranking (only included in PROMETHEE II).

2.3. Determination of Thresholds in Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment

2.3.1. Assignment of Uncertainty Classes in Life Cycle Assessment

2.3.2. Assignment of Uncertainty Classes in Social Life Cycle Assessment

2.3.3. Assignment of Uncertainty Classes in Life Cycle Costing

2.4. Weighting of Indicators

3. Case Study of Industrial Hydrogen Production by Alkaline Water Electrolysis

3.1. System Description

3.2. Indicator Results

4. PROMETHEE for Integrating LCSA of Industrial Hydrogen Production

4.1. PROMETHEE Results with Common Default Thresholds for Uncertainty in General

4.2. PROMETHEE Results with Specified Thresholds Based on Uncertainty in Life Cycle Impact Assessment

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UN. Adoption of the Paris Agreement, Framework Convention on Climate Change; United Nations: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. The European Green Deal; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fuel Cell and Hydrogen Joint Undertaking. Hydrogen Roadmap Europe; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ram, M.; Bogdanov, D.; Aghahosseini, A.; Khalili, S.; Child, M.; Fasihi, M.; Traber, T.; Breye, C. Global Energy System Based on 100% Renewable Energy—Power, Heat, Transport and Desalination Sectors; Lappeenranta University of Technology, Energy Watch Group: Berlin, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- IEA. The Future of Hydrogen: Seizing Today’s Opportunities—Report Prepared by the IEA for the G20, Japan; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Grunwald, A.; Rösch, C. Sustainability assessment of energy technologies: Towards an integrative framework. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2011, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ciroth, A.; Finkbeiner, M.; Traverso, M.; Hildenbrand, J.; Kloepffer, W.; Mazijn, B.; Prakash, S.; Sonnemann, G.; Valdivia, S.; Ugaya, C.M.L.; et al. Towards a Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment: Making Informed Choices on Products; UNEP/SETAC Life Cycle Initiative: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Prado, V.; Rogers, K.; Seager, T.P. Integration of MCDA Tools in Valuation of Comparative Life Cycle Assessment. In Life Cycle Assessment Handbook; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 413–431. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M. Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis Tool; The University of Manchester: Manchester, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- OECD; JRC. Handbook on Constructing Composite Indicators Methodology and User Guide; OECD: Paris, France, 2008; p. 158S. [Google Scholar]

- Bouyssou, D. Building Criteria: A Prerequisite for MCDA; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1990; pp. 58–80. [Google Scholar]

- Monghasemi, S. Re: Why Promethee Offers More Preference Functions to Select From? Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/post/Why-PROMETHEE-offers-more-preference-functions-to-select-from/55f1f9685cd9e3bbb58b45c0/citation/download (accessed on 11 November 2020).

- Vinodh, S.; Girubha, R.J. Promethee based sustainable concept selection. Appl. Math. Model. 2012, 36, 5301–5308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, A.; Iribarren, D.; Dufour, J. Life cycle sustainability assessment of hydrogen from biomass gasification: A comparison with conventional hydrogen. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 21193–21203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulf, C.; Werker, J.; Zapp, P.; Schreiber, A.; Schlör, H.; Kuckshinrichs, W. Sustainable Development Goals as a Guideline for Indicator Selection in Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment. Procedia CIRP 2018, 69, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Toniolo, S. Life cycle sustainability decision-support framework for ranking of hydrogen production pathways under uncertainties: An interval multi-criteria decision making approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 175, 222–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koj, J.C.; Wulf, C.; Schreiber, A.; Zapp, P. Site-Dependent Environmental Impacts of Industrial Hydrogen Production by Alkaline Water Electrolysis. Energies 2017, 10, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kuckshinrichs, W.; Ketelaer, T.; Koj, J.C. Economic Analysis of Improved Alkaline Water Electrolysis. Front. Energy Res. 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Werker, J.; Wulf, C.; Zapp, P. Working conditions in hydrogen production: A social life cycle assessment. J. Ind. Ecol. 2019, 23, 1052–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulf, C.; Werker, J.; Ball, C.; Zapp, P.; Kuckshinrichs, W. Review of Sustainability Assessment Approaches Based on Life Cycles. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- UNEP. Guidelines for Social Life Cycle Assessment of Products and Organizations 2020; United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP): Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Eisfeldt, F.; Ciroth, A. PSILCA—A Product Social Impact Life Cycle Assessment Database Database Version 2; GreenDelta: Berlin, Germany, 2017; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- EU-JRC. Recommendations for Life Cycle Impact Assessment in the European Context—Based on Existing Environmental Impact Assessment Models and Factors; European Commission-Joint Research Centre—Institute for Environment and Sustainability: Luxembourg, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP SETAC. Global Guidance for Life Cycle Impact Assessment Indicators: Volume 1; United Nations Environment Programme, Sustainable Lifestyles, Cities and Industry Branch: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP SETAC. Global Guidance on Environmental Life Cycle Impact Assessment Indicators: Volume 2; United Nations Environment Programme, Sustainable Lifestyles, Cities and Industry Branch: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Boulay, A.-M.; Bare, J.; Benini, L.; Berger, M.; Lathuillière, M.J.; Manzardo, A.; Margni, M.; Motoshita, M.; Núñez, M.; Pastor, A.V.; et al. The WULCA consensus characterization model for water scarcity footprints: Assessing impacts of water consumption based on available water remaining (AWARE). Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2018, 23, 368–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- thinkstep. GaBi Ts; thinkstep: Leinfelden-Echterdingen, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Swiss Centre for Live Cycle Inventories. Ecoinvent Database Version 3.3; Ecoinvent: Zurich, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- thinkstep. GaBi Databases Upgrades & Improvements: 2017 Edition; thinkstep AG: Leinfelden-Echterdingen, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Okano, K. Life Cycle Costing-An Approach to Life Cycle Cost Management: A Consideration from Historical Development. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2001, 6, 317–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpi, E.; Ala-Risku, T. Life cycle costing: A review of published case studies. Manag. Audit. J. 2008, 23, 240–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- European Investment Bank. The Economic Appraisal of Investment Projects at the EIB; European Investment Bank: Luxembourg, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Branker, K.; Pathak, M.; Pearce, J. A review of solar photovoltaic levelized cost of electricity. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 4470–4482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- GreenDelta. OpenLCA; GreenDelta GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, E.S.; United Nations Environment Programme. Guidelines for Social Life Cycle Assessment of Products: Social and Socio-Economic LCA Guidelines Complementing Environmental LCA and Life Cycle Costing, Contributing to the Full Assessment of Goods and Services within the Context of Sustainable Development; United Nations Environment Programme: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, C.B.; Traverso, M.; Valdivia, S.; Vickery-Niedermann, G.; Franze, J.; Azuero, L.; Ciroth, A.; Mazijn, B.; Aulisio, D. The Methodological Sheets for Subcategories in Social Life Cycle Assessment (S-LCA); UNEP/SETAC: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Michiels, F.; Geeraerd, A. How to decide and visualize whether uncertainty or variability is dominating in life cycle assessment results: A systematic review. Environ. Model. Softw. 2020, 133, 104841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, R.K.; Georgiadis, S.; Fantke, P. Uncertainty Management and Sensitivity Anlayis. In Life Cycle Assessment: Theory and Practice; Hauschild, M.Z., Rosenbaum, R.K., Olsen, S.I., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2018; pp. 271–322. [Google Scholar]

- Benetto, E.; Dujet, C.; Rousseaux, P. Integrating fuzzy multicriteria analysis and uncertainty evaluation in life cycle assessment. Environ. Model. Softw. 2008, 23, 1461–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Ren, X.; Liang, H.; Dong, L.; Zhang, L.; Luo, X.; Yang, Y.; Gao, Z. Multi-actor multi-criteria sustainability assessment framework for energy and industrial systems in life cycle perspective under uncertainties. Part 2: Improved extension theory. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2016, 22, 1406–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J. Multi-criteria decision making for the prioritization of energy systems under uncertainties after life cycle sustainability assessment. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2018, 16, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Cucurachi, S.; Suh, S. Perceived uncertainties of characterization in LCA: A survey. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2020, 25, 1846–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, S.; Cerutti, A.K.; Pant, R. Development of a Weighting Approach for the Environmental Footprint; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, B. Classement et choix en présence de points de vue multiples. Rev. Fr. D’inform. Rech. Opérationnelle 1968, 2, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brans, J.; Vincke, P.; Mareschal, B. How to select and how to rank projects: The Promethee method. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1986, 24, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behzadian, M.; Kazemzadeh, R.; Albadvi, A.; Aghdasi, M. Promethee: A comprehensive literature review on methodologies and applications. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2010, 200, 198–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brans, J.P. L’ingénièrie de la décision. Elaboration d’instruments d’aide à la décision. La méthode promethee. In L’aide à La Décision: Nature, Instruments et Perspectives d’Avenir; Nadeau, R., Landry, M., Eds.; Presses de l’Université Laval: Québec, QC, Canada, 1982; pp. 183–213. [Google Scholar]

- Brans, J.-P.; Mareschal, B. Promethee Methods. In Multiple Criteria Decision Analysis: State of the Art Surveys; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brans, J.P.; Vincke, P. Note—A Preference Ranking Organisation Method. Manag. Sci. 1985, 31, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mareschal, B. How to Choose the Correct Preference Function; e-PROMETHEE Days: Rabat, Morocco, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hyde, K.; Maier, H.R.; Colby, C. Incorporating uncertainty in the PROMETHEE MCDA method. J. Multi Criteria Decis. Anal. 2003, 12, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Xu, D.; Cao, H.; Wei, S.; Dong, L.; Goodsite, M.E. Sustainability decision support framework for industrial system prioritization. AIChE J. 2015, 62, 108–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, K.; Seager, T.; Linkov, I. Multicriteria Decision Analysis and Life Cycle Assessment. In Real-Time and Deliberative Decision Making; Linkov, I., Ferguson, E., Magar, V.S., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 305–314. [Google Scholar]

- do Carmo, B.B.T.; Margni, M.; Baptiste, P. Propagating Uncertainty in Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment into Decision-Making Problems: A Multiple Criteria Decision Aid Approach. In Designing Sustainable Technologies, Products and Policies: From Science to Innovation; Benetto, E., Gericke, K., Guiton, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Germany, 2018; pp. 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Li, W.; Ding, S.; Dong, L. Sustainability assessment and decision making of hydrogen production technologies: A novel two-stage multi-criteria decision making method. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltran, A.M.; Prado, V.; Vivanco, D.F.; Henriksson, P.J.; Guinée, J.B.; Heijungs, R. Quantified Uncertainties in Comparative Life Cycle Assessment: What Can Be Concluded? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 2152–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Salminen, P.; Hokkanen, J.; Lahdelma, R. Comparing multicriteria methods in the context of environmental problems. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1998, 104, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heijungs, R. Uncertainty Analysis in LCA Concepts, Tools, and Practice; Institute of Environmental Sciences (CML), Leiden University: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hauschild, M.Z.; Goedkoop, M.; Guinée, J.; Heijungs, R.; Huijbregts, M.; Jolliet, O.; Margni, M.; De Schryver, A.; Humbert, S.; Laurent, A.; et al. Identifying best existing practice for characterization modeling in life cycle impact assessment. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2013, 18, 683–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humbert, S.; Rossi, V.; Margni, M.; Jolliet, O.; Loerincik, Y. Life cycle assessment of two baby food packaging alternatives: Glass jars vs. plastic pots. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2009, 14, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chhipi-Shrestha, G.K.; Hewage, K.; Sadiq, R. ‘Socializing’ sustainability: A critical review on current development status of social life cycle impact assessment method. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2014, 17, 579–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, M.; Babenhauserheide, N.; Rösch, C. Multi criteria decision analysis for sustainability assessment of 2nd generation biofuels. Procedia CIRP 2020, 90, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotfi, F.H.; Fallahnejad, R. Imprecise Shannon’s Entropy and Multi Attribute Decision Making. Entropy 2010, 12, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wulf, C.; Zapp, P.; Schreiber, A.; Kuckshinrichs, W. Integrated Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment—Hydrogen production as a showcase for an emerging methodology. In Towards Sustainable Future. Current Challenges and Prospects in the Life Cycle Management—LCM 2019; Kasprzak, J., Ed.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Koj, J.C.; Schreiber, A.; Zapp, P.; Marcuello, P. Life Cycle Assessment of Improved High Pressure Alkaline Electrolysis. Energy Procedia 2015, 75, 2871–2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hermann, H.; Emele, L.; Loreck, C. Prüfung der Klimapolitischen Konsistenz und der Kosten von Methanisierungsstrategien; Öko-Institut e.V.: Freiburg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Statista. Prices of Electricity for Industrial Customers in Austria from 2008 to 2020. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/596258/electricity-industry-price-austria/ (accessed on 17 May 2021).

| Type | Example Life Cycle Inventory | Example Life Cycle Impact Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Parameter uncertainty | Inaccurate data | Lifetimes of substances |

| Model uncertainty | Assuming linearity | Assuming steady-state conditions |

| Scenario uncertainty | Technology level | Characterization method (TAP500 or Accumulated Exceedance) |

| Epistemological uncertainty | Ignorance | Ignorance |

| Relevance uncertainty | - | Concentrating on indigenous rights with a product system centered in Western Europe |

| Mistakes | Mixing up kWh and MJ | Wrong characterization factor for flows |

| Uncertainty Class | Q′Spec | P′Spec |

|---|---|---|

| 1.0 | 10% | 20% |

| 1.5 | 20% | 30% |

| 2.0 | 30% | 40% |

| 2.5 | 50% | 60% |

| 3.0 | 70% | 80% |

| 3.5 | 90% | 100% |

| Impact Category | Uncertainty Class | Weak Preference Zone Q′Spec–P′Spec |

|---|---|---|

| Climate change | 1 | 10–20% |

| Ozone depletion | 1 | 10–20% |

| Cumulated energy demand | 1 | 10–20% |

| Resource depletion, water | 2 | 30–40% |

| Resource depletion, mineral | 2 | 30–40% |

| Particulate matter/respiratory inorganics | 2 | 30–40% |

| Ionizing radiation, human health | 2 | 30–40% |

| Photochemical ozone formation | 2 | 30–40% |

| Acidification | 2 | 30–40% |

| Terrestrial eutrophication | 2 | 30–40% |

| Aquatic eutrophication | 2 | 30–40% |

| Marine eutrophication | 2 | 30–40% |

| Ecotoxicity, freshwater | 3 | 70–80% |

| Human toxicity, cancer | 3 | 70–80% |

| Human toxicity, non-cancer | 3 | 70–80% |

| Impact Category | Uncertainty Class | Weak Preference Zone Q′Spec–P′Spec |

|---|---|---|

| Women in the sectoral labour force | 1.0 | 10–20% |

| Life expectancy at birth | 1.0 | 10–20% |

| Social security expenditures | 1.0 | 10–20% |

| Unemployment | 1.0 | 10–20% |

| Weekly hours of work per employee * | 1.5 | 20–30% |

| Gender wage gap | 1.5 | 20–30% |

| Net migration | 1.5 | 20–30% |

| Health expenditure | 1.5 | 20–30% |

| International migrant stock | 1.5 | 20–30% |

| Fatal accidents | 1.5 | 20–30% |

| Child labour, total * | 2.0 | 30–40% |

| Public sector corruption * | 2.0 | 30–40% |

| Trafficking in persons * | 2.0 | 30–40% |

| Non-fatal accidents | 2.0 | 30–40% |

| Certified environmental management system | 2.0 | 30–40% |

| Indigenous rights | 2.0 | 30–40% |

| Education | 2.0 | 30–40% |

| Illiteracy, total | 2.0 | 30–40% |

| Youth illiteracy, total | 2.0 | 30–40% |

| Fair salary | 2.0 | 30–40% |

| Association and bargaining rights | 2.0 | 30–40% |

| Trade union density | 2.0 | 30–40% |

| Social responsibility along the supply chain | 2.5 | 50–60% |

| Drinking water coverage | 2.5 | 50–60% |

| Sanitation coverage | 2.5 | 50–60% |

| International migrant workers (in the sector/site) * | 3.0 | 70–80% |

| Active involvement of enterprises in corruption and bribery * | 3.0 | 70–80% |

| Frequency of forced labour * | 3.0 | 70–80% |

| Safety measures | 3.0 | 70–80% |

| Workers affected by natural disasters | 3.0 | 70–80% |

| Violations of employment laws and regulations * | 3.5 | 90–100% |

| Goods produced by forced labour * | 3.5 | 90–100% |

| Anti-competitive behavior or violation of anti-trust and monopoly legislation * | 3.5 | 90–100% |

| Presence of business practices deceptive or unfair to consumers * | 3.5 | 90–100% |

| Unit Per kg H2 | DE | AT | ES | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electricity | kWhel | 53.9 | Electricity and district heat | Electrical energy, gas, steam and hot water | Production and distribution of electricity |

| Water, de-ionized | kg | 10.11 | Water supply | Collection, purification and distribution of water | Collection, purification and distribution of water |

| KOH solution | mg | 275 | Manufacture of chemical products | Chemicals, chemical products and man-made fibres | Basic chemical products |

| Process steam (Natural gas and heating oil for steam from water) | g | 38 | Gas supply/Coal, coke and petroleum products, nuclear fuels/Water supply | Electrical energy, gas, steam and hot water/Coke, refined petroleum products and nuclear fuel/Collection, purification and distribution of water | Manufacture and distribution of gas/Coke, refined petroleum products and nuclear fuel/Collection, purification and distribution of water |

| Nitrogen | mg | 71.15 | Manufacture of chemical products | Chemicals, chemical products and man-made fibres | Basic chemical products |

| Indicator | Unit | DE | AT | ES |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LCA | ||||

| Acidification | mMole H+ eq. | 44.5 | 21.6 | 50.3 |

| Climate change | kg CO2 eq. | 29.8 | 10.2 | 16.2 |

| Cumulative energy demand | MJ | 534 | 341 | 513 |

| Ecotoxicity, freshwater | CTUe | 5.59 | 3.31 | 3.71 |

| Eutrophication, marine | g N eq. | 11.2 | 7.31 | 11.6 |

| Eutrophication, freshwater | mg P eq. | 128 | 133 | 93 |

| Eutrophication, terrestrial | mMole N eq. | 116 | 65 | 121 |

| Human toxicity cancer | nCTUh | 37.5 | 14.8 | 27.1 |

| Human toxicity non-cancer | nCTUh | 977 | 507 | 434 |

| Ionizing radiation | Bq U235 eq. | 2760 | 32 | 3200 |

| Ozone depletion | ng CFC-11 eq. | 63.2 | 43.8 | 50.3 |

| Particulate matter | mg PM2.5 eq. | 2000 | 870 | 246 |

| Photochemical ozone creation | g NMVOC | 30.0 | 16.4 | 33.0 |

| Resource depletion—Abiotic resources | mg Sb eq. | 129 | 388 | 938 |

| Resource depletion—Water | m3 world eq. | 23.6 | 23.9 | 43.9 |

| LCC | ||||

| Levelized cost of hydrogen | €2015/kg H2 | 3.64 | 4.22 | 4.31 |

| Profitability index * | - | −6.38 | −7.45 | −7.74 |

| Net present value * | m€2015/kg H2 | −50.1 | −58.1 | −59.4 |

| Marginal cost | €2015/kg H2 | 3.72 | 4.52 | 4.73 |

| S-LCA | ||||

| Active involvement of enterprises in corruption and bribery | Med. Rh | 2.15 | 2.94 | 4.55 |

| Association and bargaining rights | Med. Rh | 6.54 | 16.48 | 1.81 |

| Certified environmental management system | Med. Rh | 19.41 | 37.19 | 20.47 |

| Child labour, total | Med. Rh | 0.98 | 1.08 | 0.60 |

| Drinking water coverage | Med. Rh | 2.60 | 2.90 | 1.65 |

| Education | Med. Rh | 3.01 | 2.32 | 4.56 |

| Fair salary | Med. Rh | 5.46 | 7.73 | 2.30 |

| Fatal accidents | Med. Rh | 0.40 | 0.55 | 0.26 |

| Frequency of forced labour | Med. Rh | 0.46 | 0.57 | 0.16 |

| Gender wage gap | Med. Rh | 5.47 | 31.94 | 7.96 |

| Goods produced by forced labour | Med. Rh | 0.30 | 0.29 | 0.22 |

| Health expenditure | Med. Rh | 6.07 | 6.24 | 3.59 |

| Illiteracy, total | Med. Rh | 4.45 | 4.43 | 2.21 |

| Indigenous rights | Med. Rh | 1.44 | 1.79 | 0.78 |

| Non-fatal accidents | Med. Rh | 4.03 | 13.82 | 27.12 |

| Public sector corruption | Med. Rh | 15.99 | 16.85 | 12.68 |

| Safety measures | Med. Rh | 4.89 | 5.71 | 5.15 |

| Sanitation coverage | Med. Rh | 13.89 | 14.17 | 8.15 |

| Social security expenditures | Med. Rh | 5.79 | 5.72 | 2.62 |

| Trade union density | Med. Rh | 25.75 | 18.46 | 43.89 |

| Trafficking in persons | Med. Rh | 2.30 | 2.81 | 1.34 |

| Unemployment | Med. Rh | 0.81 | 0.77 | 37.43 |

| Violations of employment laws and regulations | Med. Rh | 1.93 | 3.22 | 3.04 |

| Weekly hours of work per employee | Med. Rh | 0.26 | 0.48 | 0.45 |

| Women in the sectoral labour force | Med. Rh | 1.85 | 1.93 | 3.93 |

| Youth illiteracy, total | Med. Rh | 0.75 | 0.81 | 0.45 |

| Indicator | Unit | qDef | pDef | Deviation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DE-AT | DE-ES | AT-ES | ||||

| LCA | ||||||

| Acidification | mMole H+ eq. | 1.08 | 2.16 | 22.90 | 5.8 | 28.70 |

| Climate change | kg CO2 eq. | 0.51 | 1.02 | 19.60 | 13.60 | 6.00 |

| Cumulative energy demand | MJ | 17.1 | 34.1 | 193.0 | 21.0 | 172.0 |

| Ecosystem toxicity, freshwater | CTUe | 0.17 | 0.33 | 2.28 | 1.88 | 0.40 |

| Eutrophication, marine | g N eq. | 0.36 | 0.73 | 3.89 | 0.40 | 4.29 |

| Eutrophication, freshwater | mg P eq. | 4.66 | 9.32 | 5.00 | 34.80 | 39.80 |

| Eutrophication, terrestrial | mMole N eq. | 3.25 | 6.5 | 51.00 | 5.00 | 56.00 |

| Human toxicity cancer | nCTUh | 0.74 | 1.48 | 22.70 | 10.40 | 12.3 |

| Human toxicity non-cancer | nCTUh | 21.7 | 43.4 | 470 | 543 | 73.0 |

| Ionizing radiation | mBq U235 eq. | 1.64 | 3.28 | 2727 | 440 | 3170 |

| Ozone depletion | ng CFC-11 eq. | 2.19 | 4.38 | 19.40 | 12.90 | 6.50 |

| Particulate matter | mg PM2.5 eq. | 43.5 | 87.0 | 1130 | 460 | 1590 |

| Photochemical ozone creation | g NMVOC | 0.82 | 1.64 | 13.60 | 3.00 | 16.60 |

| Resource depletion—Abiotic resources | mg Sb eq. | 1.94 | 3.88 | 90.2 | 35.2 | 55.0 |

| Resource depletion—Water | m3 world eq. | 1.18 | 2.36 | 0.28 | 20.30 | 20.02 |

| LCC | ||||||

| Levelized cost of hydrogen | €2015/kg H2 | 0.182 | 0.364 | 0.580 | 0.670 | 0.090 |

| Net present value | m€2015/kg H2 | 2.97 * | 5.94 * | 8.00 * | 9.30 * | 1.30 * |

| Profitability index | - | 0.387 * | 0.774 * | 1.070 * | 1.360 * | 0.290 * |

| Marginal cost | €2015/kg H2 | 0.186 | 0.372 | 0.800 | 1.010 | 0.210 |

| S-LCA | ||||||

| Active involvement of enterprises in corruption and bribery | Med. Rh | 0.11 | 0.21 | 0.80 | 2.40 | 1.61 |

| Association and bargaining rights | Med. Rh | 0.09 | 0.18 | 9.94 | 4.73 | 14.67 |

| Certified environmental management system | Med. Rh | 0.97 | 1.94 | 17.77 | 1.05 | 16.72 |

| Child labour | Med. Rh | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.38 | 0.48 |

| Drinking water coverage | Med. Rh | 0.08 | 0.17 | 0.30 | 0.95 | 1.24 |

| Education | Med. Rh | 0.12 | 0.23 | 0.69 | 1.55 | 2.24 |

| Fair salary | Med. Rh | 0.12 | 0.23 | 2.27 | 3.16 | 5.43 |

| Fatal accidents | Med. Rh | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.29 |

| Frequency of forced labour | Med. Rh | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.29 | 0.41 |

| Gender wage gap | Med. Rh | 0.27 | 0.55 | 26.47 | 2.49 | 23.98 |

| Goods produced by forced labour | Med. Rh | 0.011 | 0.022 | 0.008 | 0.080 | 0.072 |

| Health expenditure | Med. Rh | 0.18 | 0.36 | 0.17 | 2.47 | 2.65 |

| Illiteracy, total | Med. Rh | 0.11 | 0.22 | 0.02 | 2.25 | 2.23 |

| Indigenous rights | Med. Rh | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.35 | 0.66 | 1.02 |

| Non-fatal accidents | Med. Rh | 0.20 | 0.40 | 9.78 | 23.09 | 13.31 |

| Public sector corruption | Med. Rh | 0.63 | 1.27 | 0.87 | 3.31 | 4.17 |

| Safety measures | Med. Rh | 0.24 | 0.49 | 0.82 | 0.26 | 0.57 |

| Sanitation coverage | Med. Rh | 0.41 | 0.82 | 0.28 | 5.74 | 6.02 |

| Social security expenditures | Med. Rh | 0.13 | 0.26 | 0.07 | 3.17 | 3.10 |

| Trade union density | Med. Rh | 0.92 | 1.85 | 7.29 | 18.14 | 25.43 |

| Trafficking in persons | Med. Rh | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.52 | 0.96 | 1.48 |

| Unemployment | Med. Rh | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 36.62 | 36.66 |

| Violations of employment laws and regulations | Med. Rh | 0.10 | 0.19 | 1.29 | 1.11 | 0.18 |

| Weekly hours of work per employee | Med. Rh | 0.013 | 0.026 | 0.212 | 0.181 | 0.030 |

| Women in the sectoral labour force | Med. Rh | 0.09 | 0.19 | 0.07 | 2.07 | 2.00 |

| Youth illiteracy, total | Med. Rh | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.30 | 0.36 |

| Default Thresholds | Indicator Specified Thresholds | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicator | Unit | q′Def | p′Def | q′Spec | p′Spec |

| LCA | |||||

| Acidification | mMole H+ eq. | 1.08 | 2.16 | 6.48 | 8.64 |

| Climate change | kg CO2 eq. | 0.51 | 1.02 | 1.02 | 2.04 |

| Cumulative energy demand | MJ | 17.1 | 34.1 | 34.1 | 68.2 |

| Ecosystem toxicity, freshwater | CTUe | 0.17 | 0.33 | 2.32 | 2.65 |

| Eutrophication, marine | g N eq. | 0.36 | 0.73 | 2.19 | 2.92 |

| Eutrophication, freshwater | mg P eq. | 4.66 | 9.32 | 28.0 | 37.3 |

| Eutrophication, terrestrial | mMole N eq. | 3.25 | 6.5 | 19.5 | 26.0 |

| Human toxicity cancer | nCTUh | 0.74 | 1.48 | 10.4 | 11.8 |

| Human toxicity non-cancer | nCTUh | 21.7 | 43.4 | 304 | 347 |

| Ionizing radiation | mBq U235 eq. | 1.64 | 3.28 | 9.8 | 13.1 |

| Ozone depletion | ng CFC-11 eq. | 2.19 | 4.38 | 4.38 | 8.76 |

| Particulate matter | mg PM2.5 eq. | 43.5 | 87.0 | 261 | 348 |

| Photochemical ozone creation | g NMVOC | 0.82 | 1.64 | 4.92 | 6.56 |

| Resource depletion—Abiotic resources | mg Sb eq. | 1.94 | 3.88 | 11.6 | 15.5 |

| Resource depletion—Water | m3 world eq. | 1.18 | 2.36 | 7.09 | 9.46 |

| S-LCA | |||||

| Active involvement of enterprises in corruption and bribery | Med. Rh | 0.11 | 0.21 | 1.50 | 1.72 |

| Association and bargaining rights | Med. Rh | 0.09 | 0.18 | 0.54 | 0.72 |

| Certified environmental management system | Med. Rh | 0.97 | 1.94 | 5.82 | 7.77 |

| Child labour, total | Med. Rh | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.18 | 0.24 |

| Drinking water coverage | Med. Rh | 0.08 | 0.17 | 0.83 | 0.99 |

| Education | Med. Rh | 0.12 | 0.23 | 0.69 | 0.93 |

| Fair salary | Med. Rh | 0.12 | 0.23 | 0.69 | 0.92 |

| Fatal accidents | Med. Rh | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.08 |

| Frequency of forced labour | Med. Rh | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.13 |

| Gender wage gap | Med. Rh | 0.27 | 0.55 | 1.09 | 1.64 |

| Goods produced by forced labour | Med. Rh | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.20 | 0.22 |

| Health expenditure | Med. Rh | 0.18 | 0.36 | 0.72 | 1.08 |

| Illiteracy, total | Med. Rh | 0.11 | 0.22 | 0.66 | 0.88 |

| Indigenous rights | Med. Rh | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.23 | 0.31 |

| Non-fatal accidents | Med. Rh | 0.20 | 0.40 | 1.21 | 1.61 |

| Public sector corruption | Med. Rh | 0.63 | 1.27 | 3.80 | 5.07 |

| Safety measures | Med. Rh | 0.24 | 0.49 | 3.42 | 3.91 |

| Sanitation coverage | Med. Rh | 0.41 | 0.82 | 4.08 | 4.89 |

| Social security expenditures | Med. Rh | 0.13 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.52 |

| Trade union density | Med. Rh | 0.92 | 1.85 | 5.54 | 7.38 |

| Trafficking in persons | Med. Rh | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.40 | 0.53 |

| Unemployment | Med. Rh | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.15 |

| Violations of employment laws and regulations | Med. Rh | 0.10 | 0.19 | 1.74 | 1.93 |

| Weekly hours of work per employee | Med. Rh | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.08 |

| Women in the sectoral labour force | Med. Rh | 0.09 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.37 |

| Youth illiteracy, total | Med. Rh | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.18 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wulf, C.; Zapp, P.; Schreiber, A.; Kuckshinrichs, W. Setting Thresholds to Define Indifferences and Preferences in PROMETHEE for Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment of European Hydrogen Production. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7009. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137009

Wulf C, Zapp P, Schreiber A, Kuckshinrichs W. Setting Thresholds to Define Indifferences and Preferences in PROMETHEE for Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment of European Hydrogen Production. Sustainability. 2021; 13(13):7009. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137009

Chicago/Turabian StyleWulf, Christina, Petra Zapp, Andrea Schreiber, and Wilhelm Kuckshinrichs. 2021. "Setting Thresholds to Define Indifferences and Preferences in PROMETHEE for Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment of European Hydrogen Production" Sustainability 13, no. 13: 7009. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137009

APA StyleWulf, C., Zapp, P., Schreiber, A., & Kuckshinrichs, W. (2021). Setting Thresholds to Define Indifferences and Preferences in PROMETHEE for Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment of European Hydrogen Production. Sustainability, 13(13), 7009. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137009