Language Ideologies, Practices, and Kindergarteners’ Narrative Macrostructure Development: Crucial Factors for Sustainable Development of Early Language Education

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Family Language Policy and Its Three Dimensions

2.2. Child Language Acquisition and Narrative Ability Development

2.3. Narrative Macrostructure and FLP

2.4. FLP Research in China

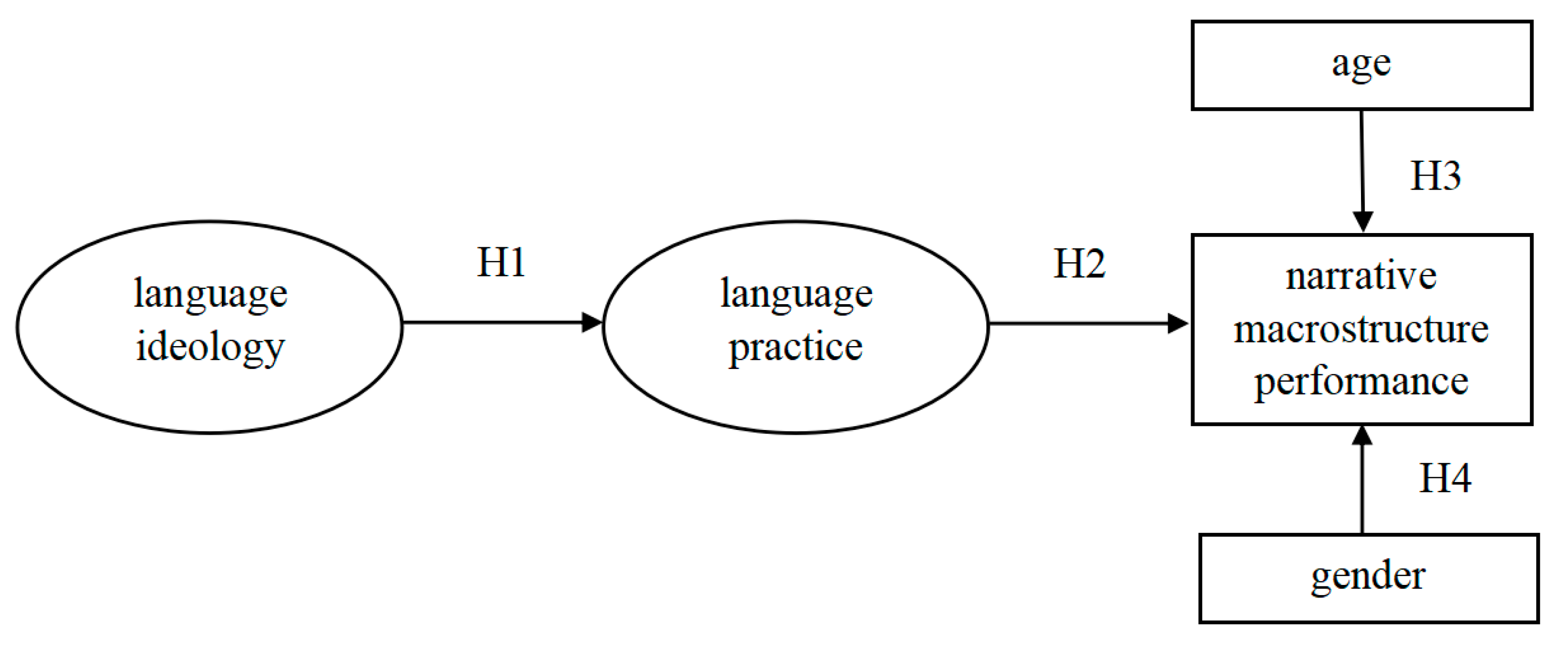

3. Research Hypothesis

4. Methodology

4.1. Research Design

4.2. Participants

4.3. Measurement of Narrative Macrostructure Performance

4.3.1. Materials

4.3.2. Procedures

4.3.3. Scoring

4.4. Measurement of Language Ideology and Language Practice

4.4.1. Materials

4.4.2. Procedures

4.4.3. Data Entry

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

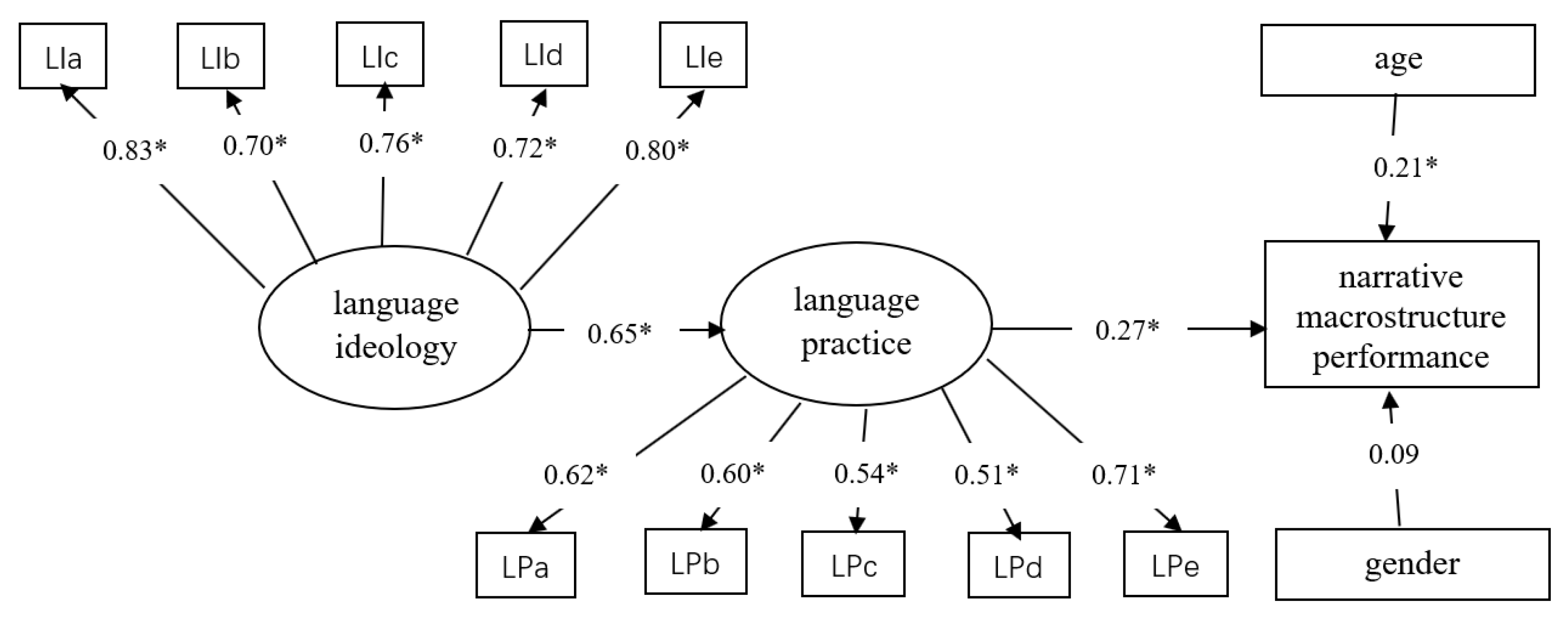

5.2. Model Evaluation

6. Discussion

6.1. Family Language Ideology Significantly Influences Family Language Practice

6.2. Family Language Practice in Turn Shapes Children’s Narrative Macrostructure Ability

6.3. Development of Narrative Macrostructure Is a Predictable and Gradually Learned Process with Cognitive and Linguistic Demands

6.4. Development of Narrative Macrostructure Shows Weak Gender Effects

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hall, N.E.; Segarra, V.R. Predicting academic performance in children with language impairment: The role of parent report. J. Commun. Disord. 2007, 40, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, B.A.; Freebairn, L.A.; Taylor, H.G. Academic outcomes in children with histories of speech sound disorders. J. Commun. Disord. 2000, 33, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, K.; Fogle, L.; Logan-Terry, A. Family language policy. Lang. Linguist. Compass 2008, 2, 907–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curdt-Christiansen, X.L. Invisible and visible language planning: Ideological factors in the family language policy of Chinese immigrant families in Quebec. Lang. Policy 2009, 8, 351–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, K.; Fogle, L. Bilingual parenting as good parenting: Parents’ perspectives on family language policy for additive bilingualism. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 2006, 9, 695–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curdt-Christiansen, X.L. Negotiating family language policy: Doing homework. In Successful Family Language Policy. Multilingual Education; Schwartz, M., Verschik, A., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 277–295. [Google Scholar]

- King, K.; Fogle, L. Family language policy and bilingual parenting. Lang. Teach. 2013, 46, 172–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, K.A. Language ideologies and heritage language education. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 2000, 3, 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spolsky, B. Family language policy-the critical domain. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2012, 33, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Ding, Y.; Song, M.L. Literacy planning: Family language policy in Chinese kindergartener families. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polkinghorne, D. Narrative Knowing and the Human Sciences; State University of New York Press: Albany, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Stadler, M.A.; Ward, G.C. Supporting the narrative development of young children. Early Child. Educ. J. 2005, 33, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, R. Language Disorders from Infancy through Adolescence: Assessment and Intervention; Mosby Elsevier: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2007; pp. 393–595. [Google Scholar]

- Houwer, A.D. Two or More Languages in Early Childhood: Some General Points and Practical Recommendations; ERIC Clearinghouse on Languages and Linguistics: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Spolsky, B. Language Policy; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Shohamy, E. Language Policy: Hidden Agendas and New Approaches; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Irvine, J.T.; Gal, S. Language ideology and linguistic differentiation. In Regimes of Language: Ideologies, Polities, and Identities; Kroskrit, P.V., Ed.; School of American Research Press: Santa Fe, NM, USA, 2000; pp. 35–84. [Google Scholar]

- Schiffman, H. Language policy and linguistic culture. In An Introduction to Language Policy: Theory and Method; Ricento, T., Ed.; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2006; pp. 111–125. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R. Building on Community Bilingualism; Caslon Publishing: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, D.; Zuñiga, C.; Henderson, K. A dual language revolution in the United States? From compensatory to enrichment bilingual education in Texas. In The Handbook of Bilingual and Multilingual Education; Wright, W., Boun, S., Garcia, O., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Malden, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 449–460. [Google Scholar]

- Spolsky, B. Language Management; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ricento, T. Language Policy. In Theory and Method; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hoff-Ginsberg, E. The relation of birth order and socioeconomic status to children’s language experience and language development. Appl. Psycholinguist. 1998, 19, 603–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoff, E.; Naigles, L. How children use input in acquiring a lexicon. Child Dev. 2002, 73, 418–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanza, E. Language Mixing in Infant Bilingualism: A Sociolinguistic Perspective; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Lanza, E. Can bilingual two-year-olds code-switch? J. Child Lang. 1992, 19, 633–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gleason, B.J. The Development of Language; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, P.; Hayward, D. Who does what to whom: Introduction of referents in children’s storytelling from pictures. Lang. Speech Hear. Serv. Sch. 2010, 41, 459–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McCabe, A.; Rollins, P.R. Assessment of preschool narrative skills. Am. J. Speech Lang. Pathol. 1994, 3, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heilmann, J.; Miller, J.F.; Nockerts, A.; Dunaway, C. Properties of the narrative scoring scheme using narrative retells in young school-age children. Am. J. Speech Lang. Pathol. 2010, 19, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burris, S.E.; Brown, D.D. When all children comprehend: Increasing the external validity of narrative comprehension development research. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Waller, A. Communication access to conversational narrative. Top. Lang. Disord. 2006, 26, 221–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, R.A.; Slobin, D.I. Relating Events in Narrative: A Crosslinguistic Developmental Study; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, K.R.; Bailey, A.L. Becoming independent storytellers: Modeling children’s development of narrative macrostructure. First Lang. 2012, 33, 68–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labov, W.; Waletzky, J. Narrative analysis: Oral versions of personal experience. In Essays on the Verbal and Visual Arts; Helm, J., Ed.; The University of Washington Press: Seattle, WA, USA, 1967; pp. 12–44. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe, A. Chameleon Readers: Teaching Children to Appreciate All Kinds of Good Stories; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 121–142. [Google Scholar]

- Minami, M. Japanese preschool children’s narrative development. First Lang. 1996, 16, 339–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macfie, J.; McElwain, N.L.; Houts, R.M.; Cox, M.J. Intergenerational transmission of role reversal between parent and child: Dyadic and family systems internal working models. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2005, 7, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isbell, R.; Sobol, J.; Lindauer, L.; Lowrance, A. The effects of storytelling and story reading on the oral language complexity and story comprehension of young children. Early Child. Educ. J. 2004, 32, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, P.; Dube, R.V. Effect of pictorial versus oral story presentation on children’s use of referring expressions in retell. First Lang. 2005, 5, 283–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.J.; Park, E.S.; Lee, K.H.; Pae, S. Analysis of narrative production abilities in lower school-age children. Commun. Sci. Disord. 2007, 1, 16–31. [Google Scholar]

- Owens, R.E. Language Development: An Introduction, 9th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, K. Developmental narratives of the experiencing child. Child Dev. Perspect. 2010, 4, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roch, M.; Florit, E.; Levorato, C. Narrative competence of Italian-English bilingual children between 5 and 7 years. Appl. Psycholinguist. 2016, 37, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, L.G.; Hayiou- Thomasb, M.E.; Hulmec, C.; Snowling, M.J. The home literacy environment as a predictor of the early literacy development of children at family-risk of dyslexia. Sci. Stud. Read. 2016, 20, 401–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puglisi, M.L.; Hulme, C.; Hamilton, L.G.; Snowling, M.J. The home literacy environment is a correlate, but perhaps not a cause, of variations in children’s language and literacy development. Sci. Stud. Read. 2017, 21, 498–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, C. The Effects of Parental Literacy Involvement and Child Reading Interest on the Development of Emergent Literacy Skills. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Milwaukee, WI, USA, 2013; p. 239. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, B.M.; Lonigan, C.J. Variation in the home literacy environment of preschool children: A cluster analytic approach. Sci. Stud. Read. 2009, 13, 146–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yin, X.R.; Li, G.F. An overview of the international research on family language policy (2000–2016). Chin. J. Lang. Policy Plan. 2017, 2, 68–79. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.Z. Theories and methods of family language policy research. Chin. J. Lang. Policy Plan. 2018, 3, 58–64. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.R. Family language policy and child language acquisition. Chin. J. Lang. Policy Plan. 2017, 2, 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, J. A review on the influence of family SES on children’s language development and its implication. Stud. Early Child. Educ. 2019, 292, 66–76. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.H.; Curdt-Christiansen, X.L. Children’s language development in Chinese Families: Urban middle class as a case. Chin. J. Lang. Policy Plan. 2017, 6, 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.; Mei, Z. Two worlds in one city: A sociopolitical perspective on Chinese urban families’ language planning. Curr. Issues Lang. Plan. 2021, 22, 383–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Curdt-Christiansen, X.L. Conflicting linguistic identities: Language choices of parents and their children in rural migrant workers’ families. Curr. Issues Lang. Plan. 2021, 22, 405–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J. Language Adaption of Chinese Migrant Preschoolers; Beijing Jiaotong University Press: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Q.; Wang, L.; Gao, X. An ecological approach to family language policy research: The case of Miao families in China. Curr. Issues Lang. Plan. 2021, 22, 427–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, M.; Han, Y. Exploring family language policy and planning among ethnic minority families in Hong Kong: Through a socio-historical and processed lens. Curr. Issues Lang. Plan. 2021, 22, 466–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Kang, M.H. Methods and approaches of foreign language policy research. Lang. Appl. 2021, 1, 16–27. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, B. Is there a child advantage in learning languages? Educ. Week 2000, 19, 39–41. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, A.; Salehi, M.; Leffler, A. Gender and developmental differences in children’s conversations. Sex Roles 1987, 16, 97–510. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, M.; Marschik, P.; Tulviste, T.; Almgren, M.; Pereira, M.P.; Wehberg, S.; Marjanovič-Umek, L.; Gayraud, F.; Kovačević, M.; Gallego, C. Differences between girls and boys in emerging language skills: Evidence from 10 language communities. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 2012, 30, 326–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiro, M. Genre and evaluation in narrative development. J. Child Lang. 2003, 30, 165–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, T.D.; Kajian, M.; Petersen, D.B.; Bilyk, N. Effects of an individualized narrative intervention on children’s storytelling and comprehension skills. J. Early Interv. 2013, 35, 243–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, M.A. What is Your Favorite Book? Using Narrative to Teach Theme Development in Persuasive Writing. Gonzaga Law Rev. 2011, 46, 3. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1604146 (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- Becker, T.; Licandro, U. Prototypical problem pictures when learning to tell: Case studies with reference to support and therapy. Lang. Promot. Speech Ther. Sch. Pract. 2014, 3, 140–146. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill, D.K.; Pearce, M.J.; Pick, J.L. Preschool children’s narratives and performance on the preschool individual achievement test–revised: Evidence of a relation between early narrative and later mathematical ability. First Lang. 2004, 24, 149–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.X. Study on the Narrative Ability of Reading Pictures in Preschool Children. Master’s Thesis, East China Normal University, Shanghai, China, 2007; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, S.; Chapman, R.S. Narrative content as described by individuals with Down syndrome and typically developing children. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2002, 45, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finney, S.J.; DiStefano, C. Non-normal and categorical data in structural equation modeling. In Structural Equation Modeling: A Second Course; Hancock, G.R., Mueller, R.O., Eds.; Information Age Publishing: Greenwich, CT, USA, 2006; pp. 269–314. [Google Scholar]

- Nevitt, J.; Hancock, G.R. Performance of bootstrapping approaches to model test statistics and parameter standard error estimation in structural equation modeling. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 2001, 8, 353–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.L. Structural Equation Modeling: Operation and Application of Amos; Chongqing University Press: Chongqing, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Feagans, L. The development and importance of narratives for school adaptation. In The Language of Children Reared in Poverty; Feagans, L., Farran, D., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1982; pp. 95–116. [Google Scholar]

- Melzi, G.; Gaspe, M. Research approaches to literacy, narrative and education. In Encyclopedia of Language and Education; Hornberger, N., King, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, G.; Tarchi, C.; Bigozzi, L. The relationship between oral and written narratives: A three-year longitudinal study of narrative cohesion, coherence, and structure. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2015, 85, 551–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spolsky, B. Introduction. In The Handbook of Educational Linguistics; Spolsky, B., Hult, F.M., Eds.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2008; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Carmiol, A.M.; Sparks, A. Narrative development across cultural contexts: Finding the pragmatic in parent-child reminiscing. In Pragmatic Development in First Language Acquisition (Trends in Language Acquisition Research); Matthews, D., Ed.; John Benjamins: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 279–293. [Google Scholar]

- Glenn-Applegate, K.; Breit-Smith, A.; Justice, L.; Piasta, S. Artfulness in young children’s spoken narratives. Early Educ. Dev. 2010, 21, 468–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean | Std. Deviation | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LIa | 4.73 | 0.67 | 1–5 |

| LIb | 4.52 | 0.86 | 1–5 |

| LIc | 4.56 | 0.88 | 1–5 |

| LId | 4.65 | 0.80 | 1–5 |

| LIe | 4.67 | 0.70 | 1–5 |

| LPa | 3.56 | 1.26 | 1–5 |

| LPb | 4.08 | 1.10 | 1–5 |

| LPc | 3.69 | 1.20 | 1–5 |

| LPd | 3.85 | 1.03 | 1–5 |

| LPe | 4.25 | 0.88 | 1–5 |

| Narrative macrostructure score | 10.71 | 2.39 | 0–19 |

| CMIN/DF | CFI | IFI | TLI | RMSEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cut-off criteria | 1–2 | >0.95 | >0.95 | >0.95 | <0.06 |

| Actual values | 1.245 | 0.967 | 0.968 | 0.960 | 0.043 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yin, J.; Ding, Y.; Fan, L. Language Ideologies, Practices, and Kindergarteners’ Narrative Macrostructure Development: Crucial Factors for Sustainable Development of Early Language Education. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6985. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13136985

Yin J, Ding Y, Fan L. Language Ideologies, Practices, and Kindergarteners’ Narrative Macrostructure Development: Crucial Factors for Sustainable Development of Early Language Education. Sustainability. 2021; 13(13):6985. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13136985

Chicago/Turabian StyleYin, Jing, Yan Ding, and Lin Fan. 2021. "Language Ideologies, Practices, and Kindergarteners’ Narrative Macrostructure Development: Crucial Factors for Sustainable Development of Early Language Education" Sustainability 13, no. 13: 6985. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13136985

APA StyleYin, J., Ding, Y., & Fan, L. (2021). Language Ideologies, Practices, and Kindergarteners’ Narrative Macrostructure Development: Crucial Factors for Sustainable Development of Early Language Education. Sustainability, 13(13), 6985. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13136985