Abstract

Health has vital importance in maintaining economic development since it is essential for, and a result of, economic development. This indicates that health makes a large contribution in achieving sustainable development and health outcomes. The significance of health is shown in the millennium development goals (MDGs) and in the sustainable development goals (SDGs), where four of the seventeen objectives focus on improving health outcomes (UN, 2021). As compared to other countries, some Asian countries are still worse off regarding health outcomes and are facing challenges in achieving positive outcomes for such goals. This study mainly focuses on identifying the link between public health expenditures and health outcomes in nine Asian economies from 2000 to 2018. The study implements fixed effects panel data estimations by using the Hausman specification test to identify the fixed effects model as the suitable estimator for the study. The empirical results from the fixed effects technique show that immunization, GDP per capita, trade openness, and utilization of basic water service facilities improve under-five and infant mortality in Asian economies. However, ecological footprint increases under-five and infant deaths by damaging the environment.

1. Introduction

Ecological footprint refers to the phenomenon or process that measures how manynatural resources we have and how many we use, consume, or destroy [1]. This phenomenon has even more importance in this day and age, where the distribution of resources is becoming more and more skewed. Some researchers suggest that consumer behavior observance should help avoid non-usage of purchased products for sustainable buying behavior and avoid binge practices [2]. Other reviewers argue that knowledge can influence the entire decision-making process of consumers [3]. The occurrence of child mortality is very high in developing countries as compared to developed countries. A death rate of one in thirteen and one in thirty-one children below the age of five was observed in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, respectively, although the rate was one in a hundred and twenty-five in developed countries [4]. Developing countries seem to be performing very poorly in reducing child mortality. Satisfactory and effective public health spending on labor force and infrastructure are extensively taken into account as predictors to improve child health status and infant mortality. The World Health Organization (WHO) assessed the worsening situation and observed that about six million children died in 2013, while this increased to an astonishing 9 million in 2019 [5]. The majority of these numbers are from the developing countries, including the countries of MDG-4, such as the Caucasus and central Asian, southern Asian, and sub-Saharan African countries.

Funding assistance becomes an essential part of health expenditure in less progressive countries, which is helpful for increasing resource allocation in vital segments of economies. Possible improved wellbeing as an outcome of the enhanced capacity of the health sector results from the proper allocation of public healthcare funds, which is the current need to improve health outcomes in selected Asian economies. Moreover, governments must play their role in reducing the overwhelming environmentally unfriendly influence of ecological footprints by forming flexible structures of institutions that can lessen ecological footprints to help recommend green growth.

Child health, infectious diseases, and malnutrition make great contributions towards child mortality [6,7,8]. A lot of infectious diseases can be prevented, while malnutrition can be diminished based on sustainable widespread health coverage. Previous research studies shave determined that the general health treatment by public funding in developing countries stops diseases through vaccination and also decreases malnutrition by supplying nutritional food.

According to [9], the simplest way to define an ecological footprint would be to “call it the impact of human activities measured in terms of the area of biologically productive land and water required to produce the goods consumed and to assimilate the wastes generated”. Thus, the term refers to the amount of the environment which is necessary in order to produce the necessary goods and services to sustain a particular lifestyle.

Suitable and effective public health expenditure on the labor force and infrastructure are extensively understood to be predictors of the progress of child health and under-five mortality [10,11,12]. However, increased health expenditure does not always result in better health outcomes due to inefficiency in spending [12].

While discussing economic development, we find a solid association of economic development and health improvement, as when an economy starts growing, it shows improved health quality and equity. Increasingly health facilities cause the labor force of an economy to become more active. For instance, the sharing economy has seen significant growth over the past few years because it allows users to use their idle resources in order to earn additional income and cultivate healthy new social connections [13]. Other researchers explained the growth of the sharing economy based on the popularity of sustainable growth [14]. Some other researchers argue that international environmental agreements call for radical changes in production and also in consumption, both in industrialized and developing countries [15]. However, [16] argues that sustainable development is still a great challenge for the global economy.

For an active public health care system, it is essential that poor people have access to healthcare facilities, and processes encouraging health welfare are considered to overcome disease. The availability of funds becomes essential and many countries are in need of health-related campaigns and additional mechanisms to make improvements to public health, control different diseases, and reduce chronic illness. Effective health care programs contribute greatly to reducing infant mortality, decreasing death rates, and increasing life expectancy, in spite of poor policies and bad management of funds. In some Asian countries, a majority of the people have no access to quality health care facilities; however, major segments of the population do not understand the risk of allowing this to continue.

In several lower-middle-income economies, chronic illnesses are of prime interest for health sector officials and policy makers. There may be many reasons and motivations behind such interests; however, diseases such astuberculosis, malaria, cancer and HIV/AIDS, take an immense toll. This further increases the death toll and decreases the labor force. A nation having more advantages is one with a more worthwhile labor force, improved strength of its youths, lower child mortality rate, and the high life expectancy rate. Immunizations have higher significance in less developed countries for tracking down lifelong ailments (for instance, polio vaccine) and other life-threatening diseases. Many infants and mothers die during childbirth due to unavailability of proper healthcare and sanitation facilities. Increasing life expectancy and decreasing child mortality in developing countries are associated with the high health care expenditures.

The criteria for the distribution and amount of the funds allocated specifically for the health sector are different in different countries, but the real question is how much of those allotted expenditures are being conducting in an effective and productive manner. Generally, government expenditure policies are implemented to achieve the two main objectives:

- (1)

- To increase the overall efficiency in the allocation of the resources by encompassing its accessibility, which the private market is unable to provide optimally;

- (2)

- Governments wish to increase equity and improved resource distribution. Hence, the distribution of funds is of vital importance.

Another important factor which contributes to the hardship of developing economies is environmental degradation. A worsening environment over time is responsible for the diminution of resources such as water, soil and air. The devastation of ecosystems along with their natural habitats causes the extinction of wildlife and plants, while increasing pollution. It is clear that a disruption to the environment is supposed to be harmful or disagreeable [17]. Environmental degradation is the result of a very large and growing human population, persistently budding economic growth or per capita wealth, and the application of resource-exhausting and contaminating technology [18].

Destruction in the environment has presented a great threat to human lives on the planet. Although caused by our own actions, it is deteriorating human health and is a result of many premature deaths due to air and water pollution. Environmental degradation and pollution are two of the main reasons for almost a quarter of all deaths, or up to 234 times annually as many premature deaths happen due to conflicts, and the deaths of more than 25% of all children under the age of five. A healthy environment results in healthy people and sustainable development. Investigations highlight that climate change is worsening the scale and intensity of environment-related health risks, with the WHO guessing that 250,000 extra deaths could happen annually between 2030 and 2050 from climate-induced malnutrition, malaria, diarrhea, anxiety and heat stress [4].

The concept of sustainable development, also known as sustainability, has been defined by the Brundtland Commission “Our Common Future” in 1987 as “a development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” [19]. The basic concept of sustainability includes three major pillars, such as: economic sustainability, social sustainability, and environmental or ecological sustainability. Economic sustainability takes into account the fact that natural resources are not infinite, especially in the context of uncontrolled growth and consumption [20]. Moreover, economic sustainability represents the capacity of an economy to support a certain level of economic production (output) and long-term economic growth, without affecting the environmental, social, or cultural factors, for an indefinite period of time [21]. Some researchers consider the fact that economic sustainability assumes that the decision-making process is based on the most equitable and fiscal approach, while focusing on the other aspects of sustainability [22]. However, in order to consolidate the idea of sustainable development, it is very important that all societies implement certain transformations and adjustments to the emerging realities with respect to managing ecosystems and natural limits to growth [23]. Several researchers have found an association between public expenditure and outcomes, such as the following: [24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. Most of these studies focused on different economies, not specifically on Asian economies. These research studies also ignored the role of ecological footprint consumption, access to sanitation facilities and utilization of water services in Asian economies. Moreover, some researchers suggested that important inter-regional and intra-regional differences exist in the factors that drive capital flows [33]. Other researchers investigated the issue of capital flow drivers and argued that the category of push factors includes global risk aversion and external interest rates, while the category of pull factors includes domestic output growth, asset returns and country risk [34]. As compared to above studies, this study investigates the linkage between public health expenditure and health outcomes in selected Asian economies considering the role of immunization, government health expenditure, GDP, ecological footprint consumption, trade openness, employment rate, and utilization of water service facilities, specifically in the selected Asian economies with different contributions.

1.1. Objectives of the Study

The study aims to understand the impact of health care expenditure allocated for health sector and its proper utilization in decreasing the under-five and infant mortality rates in selected Asian economies. It also analyzes the impact of immunization, GDP, trade openness, employment rate, environmental degradation, and utilization of basic sanitation facilities on under-five and infants’ mortality rates. Moreover, the study evaluates the implications and importance of public health outcomes in selected Asian countries.

The remainder of this empirical research study is organized as follows: The first section presents the introduction accompanied by an additional framework that contributes to the understanding of the conceptual approach. Section 2 includes a wide literature review, while Section 3 highlights the selected data, research methodology and mathematical preliminaries methodology. Section 4 describes the results and discussions, while Section 5 introduces the conclusion and policy suggestions, but also future research directions.

1.2. Background

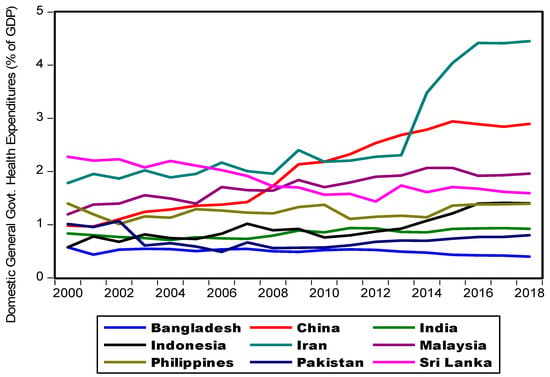

Health is vital to sustainable development. The aims of sustainable development cannot be attained in the presence of high occurrence of illness and poverty, and the health of a population cannot be maintained in the absence of a responsive health system. Public health expenditure improves health outcome in economies. The countries are allocating funds towards health programs. Figure 1 shows the trend of expenditures towards health.

Figure 1.

Government health expenditure. Source: Author’s own contribution.

Health expenditures are commonly well-defined as activities carried out either by individuals or institutions by implying paramedical, medical, technology, and/or nursing knowledge to restore, promote or maintain health. The data trend shows the lowest percentage of domestic general government health expenditures is for India (3.14) in 2016. However, high trend is observed in Sri Lanka.

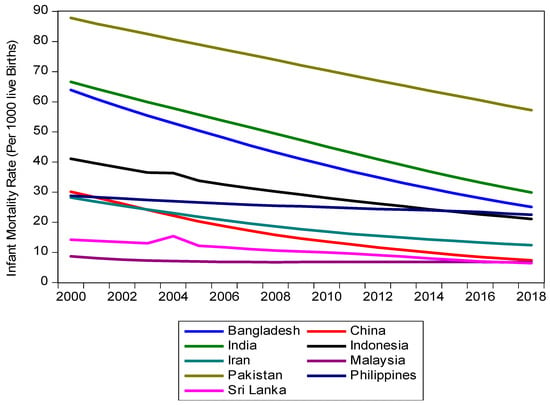

Figure 2 shows the low infant mortality rate in Malaysia and the high trend observed in Pakistan.

Figure 2.

Infant mortality rate. Source: Author’s own contribution.

1.3. Environmental Degradation

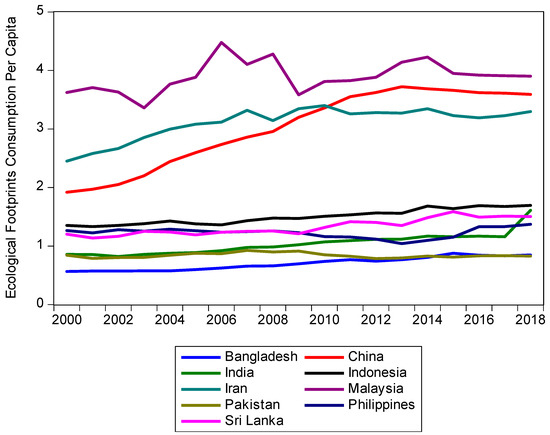

Ecological Footprint (EF) is a more comprehensive and major source of measurement of environmental damage, with greenhouse gas emissions first established by [35] and later improved by [36]. EF describes the social requirements of natural surroundings, as it gauges, by making additions of the natural accounting system, all means of natural resources required to support an economy. Ecological footprints of an economy arean overall naturally prolific land and aquatic area, in which there is need to generate resources that are consumed by societies and increased pollution caused by human activities through widespread technology [37,38]. Ecological footprint consumption is used as a proxy for environmental degradation. It basically measures the natural resource consumption by humans. We have used ecological footprint consumption per capita. This can affect under-five and infant mortality rates positively.

In Figure 3, the ecological footprints global hectares per person in Asian countries show an upward trend. However, a downward tendency is observed for Malaysia and China.

Figure 3.

Ecological footprint consumption per capita. Source: Author’s own contribution.

2. Literature Review

In this section, we provide a review of studies concerning infant mortality rates and health. A lot of work has been carried out on the relationship between health expenditure and health outcomes.

Some endogenous growth models show an association of economies’ long-term growth and public spending. Certain researchers, [39,40] among others, have observed the linkage between growth and health expenditure. Certain investigators have found out the association of sectoral public spending and health outcomes [25]. Moreover, [25], have used panel data analysis and discovered a negative effect of public health expenditures. The authors of [41] revealed that an increase in public spending improves child mortality. A negative relationship was also found between health expenditures and infant mortality rate [42,43]. Another study shows that the public spending on healthcare leads to low child mortality rates [31].

A few research studies revealed that high government expenditure is distributed and allocated less productively considering increases mortality rates [44,45,46]. The result of higher public spending on health care is not always better health outcomes due to inefficiency in spending [12]. By using panel data, [47] econometrically evaluated that economic growth is undoubtedly an important factor affecting health outcomes and government spending on health and is a significant factor in developing countries. The availability of physicians, female literacy, and child immunization also contribute to health status improvements [45].

The authors of [48] revealed that ecological footprint consumption increases infant mortality. The per capita income and growth significantly affects infant mortality [41].The authors of [49] revealed that trade tends to decrease the child mortality rate significantly in the long run. The authors of [50] concluded that unemployment increases infant mortality rate in Italy. The authors of [51] show that improved sanitation reduces infants’ death.

The authors of [52] investigated the infant and child mortality for the Republic of Uzbekistan and found out that mortality rate was higher in rural areas compared to the urban areas and was also affected by mothers’ education, child-gap, income, and infrastructure facilities. In a similar study [53] shows that infant mortality is higher in areas where mothers are less educated and belong to rural areas. For child mortality, the gap is narrow.

The authors of [54] studied infant and child mortality for the case of Jordan to observe if it can meet the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and found that sanitation facilities affect child and infant mortality more than any other factor, including the rural urban area.

According to the research of [55], no formal education of mothers, poor households and living in rural areas increase the child and infant mortality more than the environmental degradation.

The authors of [56] investigated sudden unexpected deathsud in infancyi (SUDI) occurring due to mismanagement, and overall the rates of infant death are higher in the US compared to the same standard area from Europe.

The authors of [57] examined the impact of environmental degradation on infant and child mortality for Central Asian Republics (CARs) and found that ignoring the standard factors, environmental-related issues have a severe impact on infant and child mortality.

The authors of [58] investigated if the industrial environment directly impacts infant and child mortality, especially where there is no control of industrial pollution. Poor working conditions such as dust, chemicals, fumes, gases, smoke and noise create most severe effects over paternal, infant and child mortality. The authors of [59] also discussed the contribution of environmental policies in reducing infant mortalities. The authors of [60] investigated the impact of CO2 on infant and child mortality for the case of Pakistan. The study highlights that the impact of CO2 is less significant compared to income inequalities for child mortality in the case of Pakistan and poor areas with minimum health and sanitation facilities suffer the most.

3. Data and Research Methodology

We examine the relationship between under-five mortality rate, infant mortality rate and socio-economic factors in nine selected Asian countries. For this purpose, we have panel data for the time span of 2000 to 2018. For this data analysis, we considered a cluster of certain Asian countries such as: Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, The Philippines, Iran and China. The inclusion criteria for the countries are based on the reason that the infant mortality rates among these countries vary significantly, although the government expenditures do not vary that much. The occurrence of mortality rate under-five and child mortality is very high in Asian countries and the performance of these countries is poor in terms of shortening child mortality. Considering the importance of the topic in Asian countries, the analysis has been carried out in these countries. Further, the availability of the data for ecological footprints also constrained us to limit our study to these countries. The databases on socio-economic factors have been collected from World Development Indicators (WDIs) [5]. The data for ecological footprints were drawn from the Global Footprint Network (GFN) [1].

Model Specification

We have regressed the influence of immunization, government health expenditure, ecological footprint consumption, gross domestic product, trade openness, employment rate, and utilization of basic water service facilities on under-five mortality rate alongwith infant mortality rate in selected Asian countries.

Models 1 and 2 in general form are written as follows:

Model 1

MRU = f (immunization, government health expenditures, gross domestic product, ecological footprints, trade openness, employment rate, and use of basic drinking water services).

The econometric form of the model is

MRUit = β0 + β1IMMit + β2LGHEXPit + β3GDP2it + β4EFCit + β5TROPNit + β6EMRi + β7UWSRi + µit

Model 2

IMR = f (immunization, government health expenditures, gross domestic product, ecological footprints, trade openness, employment rate, and use of basic drinking water services).

The econometric form of the model is

where the subscript “i”signifies the selected, specific countries (i = 1…9 for selected developing Asian countries), while “t” shows time specification. IMMit measures immunization (measles). MRUit indicates under-five mortality rates. IMR shows infant mortality rate (per 1000 live births). GHEXPit highlights general government health expenditures (% of GDP). GDPit shows GDP per capita PPP (Constant 2011, international). EFCit measures ecological footprint consumption per capita. TROPN shows trade openness (net exports as a percentage of GDP), whereas EMRit indicates employment rate, total (% of labor force). UWSRit is showing use of basic drinking water services (% of population). µit shows the error term.

IMRit = β0 + β1IMMit + β2LGHEXPit + β3GDP2it + β4EFCit + β5TROPNit + β6EMRi + β7UWSRi + µit

4. Results and Discussions

Initially we explain the stationary tests, descriptive statistics and consequently, we will describe the results of fixed effects model.

4.1. Stationarity Tests

In Table 1, we tested the existence of unit root in panel data. While doing this, we used different tests such as Levin, Lin and Chu, I P, Shin W-stat, ADF—Fisher Chi-square and PP—Fisher Chi-square tests. Test statistics of four methods used for GEXP, GDP, TROPN, and EMR at level form are not significant, which indicate that the data are non-stationary at level form. However, all these variables are significant at first difference. Additionally, the other variables such as MRU, UWSR and IMR are stationary at level.

Table 1.

Results of panel unit methods.

4.2. Summary Statistics

We explain the relationship between determinants of under-five mortality rate and infant mortality rate and life expectancy at birth in this section.

The descriptive statistics of the variables are presented in Table 2. Mean value and standard deviation value of IMM are 85.66 and 13.0356. Likewise, the mean value of GDP is 8540.32. On average, employment rate is 55.7413 percent in selected Asian countries. In other words, ecological footprint consumption per capita has dissimilarity in the data. EFC has a minimum value of 0.5657 and maximum value of 4.4776. GHEXP has a minimum value of 0.4242 with a maximum value of 4.4181. On average, trade openness is 64.69 percent.

Table 2.

Summary statistics of panel data used for fixed effects model.

Hausman Specification Test (HST): This test is a common technique that is used to make a comparison of random and fixed effects estimates of coefficients. For selecting FEM or REM, this test is used for both models.

For model 1, Chi2 = 61.80 and Probability of chi2 = 0.0000 and for model 2, Chi2 = 122.19 and Probability of chi2 = 0.0000.

The p-value by Hausman is in favor of fixed effects in both models.

Fixed Effects Model: Based on the results of the Hausman test, the fixed effects model is a suitable model and therefore was chosen as the appropriate fit (Table 3).

Table 3.

Determinants of under-five and infant mortality rates by fixed effects methods.

According to the Hausman specification test, the fixed effect model is thought to be the best model to test our model, assessing the factors influencing infant mortality rate and life expectancy at birth in selected Asian countries. The results of factors affecting under-five mortality rate and infant mortality rate are in the above table.

The impact of immunization is statistically significant, indicating its significant impact. The fixed effects results show that one unit increase in immunization will decrease 0.8970 units in under-five mortality per thousand.The resultshighlight that IMM negatively affects mortality. This is due to the fact that better immunization tends to decrease under-five mortality. The availability of child immunization also contributes to health status improvement [45].

GDP results showsthat it decreases under-five mortality. This means the negative coefficient indicates that a unit increase in GDP per capita decreases under-fivechild mortality per thousand in Asian economies by 0.0020 units. This shows that increasing growth is favorable in lowering child mortality in Asian countries. The possible reason for this is that if people have more per capita income, they willbe able to maintain high living standards and good health and related facilities. In this way, they enjoy an expectedly long and healthy life. The result is consistent withthe literature which shows that the public spending on healthcare leads to low child mortality rates [31].The per capita income and growth affect the infant mortalityvery significantly [41].The study results are also consistent with [46], which strengthens their validity.

In the case of spending, although showingsigns positively, the statistics are insignificant in this study, which might be explained by the percentage of the amount being spent on health, which might not have significant enough impact to be noticeable. The coefficient results are consistent withthe work of [46].

Trade openness positively affects infant mortality as well. One unit increase in trade openness decreases the mortality rate by 0.1770 units. The explanation ofthis phenomenon is that more trade openness increases the chances of high purchasing power and high incomes. These financially healthy people spendmore on education, health and nutrition, resulting in better hygiene, and all of these decrease under-five mortality.

The coefficient of employment rates isnegative but statistically insignificant. High employment rates decrease the chances of having more income. Having more income may lead to better standards of life and fulfilment of basic needs.Freedom to spend on necessities such as health and nutrition becomes easier and results in better life expectancy and decreases mortality. The authors of [50] revealed that unemployment increases infant mortality rate in the case of Italy.

Access to the use of basic drinking water services is also important factor affecting under-five mortality rates. One unit increase in basic drinking water services utilization decreases 1.2543 units under-five mortality per thousand. Provision of basic drinking water services to general public results in good health and immunization and these results in improved mortality rates.

The ecological footprint consumption is a major cause to increase under-five mortality. The coefficients indicate that one unit increase in ecological footprint consumption per capita results in an increased mortality rate by about 7.1526 children per thousand in Asian economies, whichis quite astonishing. The reason can be that polluted environment results in children being exposed to unhealthy environment, which can make the children sick, and this leads to increase under-five deaths. These results are supported by the work of [48].

The results for model 2 show that a one unit increase in immunization will decrease infants’ death per thousand by 0.5764 units. The results highlight that IMM negatively affects mortality. Better immunization tends to decrease infant mortality. The availability of child immunization also contributes to health status improvement [45].

GDP also decreases infant mortality rate. One unit increase in GDP per capita will lead to a decrease of 0.0014 units in infant mortality for Asian economies, as increasing growth improves the infant mortality in Asian countries. The possible reason for this is that if people have more per capita income, they are better able to maintain high living standards and easily spend on paternal health. In this way, they can provide a good platform for the infant who can enjoy a long and healthy life. The result is consistent with the study of [31], which shows that public spending on healthcare leads to low mortality rates. The per capita income and growth significantly affect infant mortality [41]. Results of health expenditures highlight that health expenditures improves infant mortality. A one unit increase in government health expenditure decreases infant mortality rate by about four infant deaths. However, the results are not significant in the case of health expenditures and the reasoning is the same as provided in the results of model 1, although high health expenditures result in provision of good health facilities enjoyed or accessed by the public. Resultantly, infantsand mothers have better access to medical treatment. This needs to be achievedby these economies and should raise their allocation of resources for the health sector. This situation decreases infant mortality. This result is supported by [42,43,46].

Trade openness positively affects infant mortality. A one-unit increase in trade openness results in reduction in infant death by 0.1214 units. More trade openness increases the chances of a high purchasing power and high incomes. It helps in being able to spend more on education, health and nutrition. This improves infant mortality and the results are supported by the work of [49]. The results for employment also stay insignificant for model 2 as well, which was not the desired result; however, if the coefficient was significant, it could highlight thatan increase in employment helps reduce infant mortality.

Access and use of basic drinking water services is also an important factor influencing infant mortality rates. A one unit increase in use of basic drinking water services decreases infant mortality by 0.8776 units. Provision of basic drinking water servicestothe public results in good health and immunization and this results in improved mortality rates. The current finding is also supported by the work of [51]. The ecological footprint consumption is a major cause for infant mortality. The coefficient indicates that one unit increase in ecological footprint consumption per capita will increase infant mortality by a rate of about four infant deaths per thousand. The reason for this can be that a polluted environment results in poor maternal health and consequently may result in infants’ deaths, and this leads to an increase in infant mortality. The research of [48] also observed similar patterns. Moreover, [61,62] also discussed relevant issues on health system implications, poverty and child mortality. However, sustainable criteria cover all economic, social, and environmental dimensions [63].

5. Conclusions and Discussion

Environmental degradation is a major cause for under-five and infants’ deaths given its drastic change in numbers. Health expenditure also plays an important role in reducing under-five and infant death, with an increased number of doctors and hospitals, as long as there are enough facilities to cover far-flung outreach, and improved vaccination facilities that are helpful for infants’ survival in Asian economies. The empirical results from the fixed effect technique revealed that immunization, GDP, trade openness, and utilization of basic water service facilities negatively and significantly affect under-five and infants’ mortality in Asian economies. However, ecological footprint consumption increases under-five and infant death quite significantly by damaging the environment in these selected Asian economies, while employment rate and government health expenditure, although having the correct coefficients, are insignificant, which might give further indication that governments of these countries need to take extra steps where they can allocate more resources for health sectors and create more opportunities for employment. This may bring significant results where mortality rate is moderated ominously.

There is a need to demonstrate a proper regulated mechanism framework for lessening crude deaths and improving life expectancy along with reducing mortality rates and infant death as a policy grip. Improved pure drinking water and sanitary facilities to all areas across the country require budgetary share. Irrespective of whether a family is living in a rural or urban area, access to and provision of basic facilities along with proper hygiene is a must for any country and the need for it rises manifold when it comes to Asian economies. Physicians and equipped hospital facilities are beneficial in progressing many areas of the health sector in Asian economies. Vaccination programs must be effective to decrease deaths in such economies. This research inquisitively obscures the improved policies to assuage the social plea on natural surroundings.

This research strongly endorses that governments contribute to decreasing the overwhelming environmentally friendly impact of ecological footprints by forming flexible structures of institutions that can lessen ecological footprints to help recommend green growth. Given the emphases provided through SDGs on health, nutrition as well as the ecological footprints, providing poor economies with guidance and financial help has become more easy given that there are ongoing efforts and plans ready. Asian economies just need to show willingness and act on such plans effectively. The powers should thoroughly assuage concerns regarding the quality of the environment undertheir financial changes and macroeconomic policies helpfully reduce human demand on nature and achieve constant economic growth.

In addition, there is a need to target the three main pillars of management, i.e., Man, Money and Material, to improve the overall situation with regard tohealth outcomes and a healthy environment:

- (1)

- The need is to enhance the health budget to make it compatible with population as a percentage of the total GDP.

- (2)

- Diverse health care plans should be developed at the strategic level and then implemented at the operational level in true letter and spirit to ensure the correct allotment of all resources, including the budget.

- (3)

- The sustainability of all the plans and framework to improve the mortality rates should be kept under surveillance andmust be monitored continuously at all steps of its implementation.

- (4)

- There is a dire need for doctors and paramedics not only in big cities, but also in remote areas in order to utilize their services right at the point of occurrence.

- (5)

- The number of doctors and paramedics should be matching with the quantum of workload and size of population.

- (6)

- A regular and continuous system should be in place to accentuate the capacity of the health care providers.

- (7)

- More health care establishments should be created considering the size of the population.

- (8)

- The timely and correct immunization and vaccinations of the children and infants will be effective in decreasing the infant mortality rate.

- (9)

- There should be focus on providing clean drinking water facilities, even to the remote areas, alongside fixing the problems of metropolitans.

- (10)

- Efforts must be made to clear the environment from pollution.

A future research direction involves a comparative empirical analysis between different clusters of developed and emerging countries from Europe, Asia, Africa and North America. The sample time period will be extended so as to cover certain extreme events such as the global financial crisis of 2008 and the COVID-19 pandemic, but also some less intense disturbances considering the speed of propagation and global impact, such as BREXIT, the International Debt Crisis of 1982 (Mexico), the Asian financial crisis of 1997, and others. The research methodology will be improved in the sense of using more advanced research tools, hybrid techniques based on fuzzy hybrid methods and advanced econometric modeling.

Author Contributions

D.Q.G., S.A.S.G., M.Z.N., C.S., E.C.-F., A.E. and R.B. All authors contributed equally to this research work. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Akinkugbe, O.; Mohanoe, M. Public health expenditure as a determinant of health status in Lesotho. Soc. Work Public Health 2009, 24, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemu, A.M. To what extent does access to improved sanitation explain the observed differences in infant mortality in Africa? Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2017, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amberg, N.; Fogarassy, C. Green consumer behavior in the cosmetics market. Resources 2019, 8, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagliani, M.; Bravo, G.; Dalmazzone, S. A consumption-based approach to environmental Kuznets curves using the ecological footprint indicator. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 65, 650–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bairoliya, N.; Fink, G. Causes of death and infant mortality rates among full-term births in the United States between 2010 and 2012: An observational study. PLoS Med. 2018, 15, e1002531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barro, R.J. Government spending in a simple model of endogeneous growth. J. Political. Econ. 1990, 98, 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, M.; Ghulam, H.; Hayat, M.A.; Naeem, M.Z.; Ejaz, A.; Imran, Z.A.; Spulbar, C.; Birau, R.; Gorun, T.H. How COVID-19 has shaken the sharing economy? An analysis using Google trends data. Econ. Res. Ekon. Istraživanja. [CrossRef]

- Berger, M.C.; Messer, J. Public financing of health expenditures, insurance, and health outcomes. Appl. Econ. 2002, 34, 2105–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, R.E.; Allen, L.H.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Caulfield, L.E.; De Onis, M.; Ezzati, M. Maternal and child undernutrition: Global and regional exposures and health consequences. Lancet 2008, 371, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokhari, F.A.; Gai, Y.; Gottret, P. Government health expenditures and health outcomes. Health Econ. 2007, 16, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botsman, R.; Rogers, R. How Collaborative Consumption Is Changingthe Way We Live; Harper Collins Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 1–304. [Google Scholar]

- Campagnolo, L.; Carraro, C.; Eboli, F.; Farnia, L.; Parrado, R.; Pierfederici, R. The ex-ante evaluation of achieving sustainable development goals. Soc. Indic. Res. 2018, 136, 73–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charfeddine, L. The impact of energy consumption and economic development on ecological footprint and CO2 emissions: Evidence from a Markov switching equilibrium correction model. Energy Econ. 2017, 65, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chertow, M.R. The IPAT equation and its variants. J. Ind. Ecol. 2001, 4, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chete, L.E.; Adeoye, A. Human Resources Development in Africa. The Nigerian Economic Society Selected Papers for the 2002 Annual Conference; Secretariat, Department of Economics, University of Ibadan: Oyo, Nigeria, 2002; pp. 79–102. [Google Scholar]

- Chih, C.Y.; Li, H.Y.; Yao, H.C.; Ching, C.S.; Chien, T.K. The inter-relationship among economic activities, environmental degradation, material consumption and population health in low-income countries: A longitudinal ecological study. BMJ 2015, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Dallolio, L.; Franchino, G.; Pieri, G.; Raineri, C.; Fantini, M.P. Geographical and temporal trends in infant mortality in Italy and current limits of the routine data. Epidemiol. Prev. 2011, 35, 125–130. [Google Scholar]

- Dauda, R.O.S. Health Care Spending and the Empirics of Economic Growth. J. Soc. Dev. Public Health 2004, 1, 72–82. [Google Scholar]

- Jan, D.; Awdin, A. Trade Openness and Child Mortality: A Heterogenous Panel Cointegration Analysis. Appl. Econ. 2020, 52, 2508–2525. [Google Scholar]

- Ezeh, O.K.; Agho, K.E.; Dibley, M.J.; Hall, J.J.; Page, A.N. Risk factors for post neonatal, infant, child and under-5 mortality in Nigeria: A pooled cross-sectional analysis. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e006779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filmer, D.; Pritchett, L. The impact of public spending on health: Does money matter? Soc. Med. 1999, 49, 1309–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franz, J.S.; FitzRoy, F. Child Mortality and Environment in Developing Countries. Popul. Environ. 2006, 27, 263–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genowska, A.; Jamiołkowski, J.; Szafraniec, K.; Stepaniak, U.; Szpak, A.; Pająk, A. Environmental and socio-economic determinants of infant mortality in Poland: An ecological study. Environmental health: A global access science source. Environ. Health 2015, 14, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GFN. Ecological Footprints. Retrieved from Global Footprint Network. 2021. Available online: https://www.footprintnetwork.org/our-work/ecological-footprint/ (accessed on 25 April 2021).

- Glewwe, P.; Kremer, M. Schools, Teachers, and Education Outcomes in Developing Countries. In Handbook of the Economics of Education; Hanushek, E., Welch, F., Eds.; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2006; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Gutbrod, T.; Wolke, D.; Soehne, B.; Ohrt, B.; Riegel, K. Effects of gestation and birthweight on the growth and development of very low birth weight small for gestational age infants: A matched group comparison. Archives of Disease in Childhood. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2000, 82, F208–F214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawaldar, I.T.; Ullal, M.S.; Birau, F.R.; Spulbar, C.M. Trapping Fake Discounts as Drivers of Real Revenues and Their Impact on Consumer’s Behavior in India: A Case Study. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Mendoza, R.U. Public health spending, governance and child health outcomes: Revisiting the links. J. Hum. Dev. Capab. 2013, 14, 285–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasuriya, R.; Wodon, Q. Efficiency in improving health and education outcomes: Provincial and state-level estimates for Argentina and Mexico. Estud. Econ. 2007, 22, 57–97. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, D.L.; Ambrose, S.H.; Bassett, T.; Bowen, M.L.; Johnson, D.N.; Isaacson, J.S.; Crummey, D.E.; Lamb, P.; Saul, M.; Nelson, A.W. Meanings of environmental terms. J. Environ. Qual. 1997, 26, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaldewei, C. Determinants of Infant and Under-Five Mortality—The Case of Jordan. Tech. Note. 2010, p. 1–31. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/policy/capacity/country_documents/jordan_desa_mdg4_technote_mar2010.pdf (accessed on 27 January 2021).

- Kim, S.R. Government health expenditure and public health outcomes: A comparative study among 17 countries and implications for US health care reform. Am. Int. J. Contemp. Res. 2013, 3, 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Koepke, R. What drives capital flows to emerging markets? A survey of the empirical literature. J. Econ. Surv. 2019, 33, 516–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, I.; Pradhan, M.; Sparrow, R. Health Spending and Decentralization in Indonesia. In Proceedings of the German Development Economics Conference, Frankfurt a.M. No. 33, 2009, Verein für Socialpolitik, Ausschuss für Entwicklungsländer, Göttingen, Germany; Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/39952/1/33_sparrow.pdf1 (accessed on 18 January 2021).

- Lapatinas, A.; Litina, A.; Zanaj, S. The Impact of Economic Complexity on the Formation of Environmental Culture. Sustainability 2021, 13, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, R.; Renelt, D. A Sensitivity Analysis of Cross-Country Growth Regressions. Am. Econ. Rev. 1992, 82, 942–963. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, A.D.; Mathers, C.D.; Ezzati, M.; Jamison, D.T.; Murray, C.J. Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet 2006, 367, 1747–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marfatia, H.A. The Role of Push and Pull Factors in Driving Global Capital Flows, Applied Economics Quarterly (Formerly: Konjunkturpolitik); Duncker & Humblot GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2016; Volume 62, pp. 117–146. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, F.D.; Wolf, H.C. Comparative Life Expectancy in Africa. 2001. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=632736 (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- Mensah, J. Sustainable development: Meaning, history, principles, pillars, and implications for human action: Literature review. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2019, 5, 1653531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M.Z.; Arshad, S.; Birau, R.; Spulbar, C.; Ejaz, A.; Hayat, M.A.; Popescu, J. Investigating the impact of CO2 emission and economic factors on infants health: A case study for Pakistan. Ind. Text. 2021, 72, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nethravathi, P.S.R.; Bai, G.V.; Spulbar, C.; Suhan, M.; Birau, R.; Calugaru, T.; Hawaldar, I.T.; Ejaz, A. Business intelligence appraisal based on customer behaviour profile by using hobby based opinion mining in India: A case study. Econ. Res. Ekon. Istraživanja 2020, 33, 1889–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, J.; Ulmann, P. The relationship between health care expenditure and health outcomes. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2006, 7, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odusola, A.E. Rekindling Investment and Economic Development in Nigeria. NES Selected Papers for the 1998 Annual Conference; Nigerian Economic Society, Secretariat, Department of Economics, University of Idaban: Oyo, Nigeria, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard, C.; Williams, R. Poverty and child (0–14 years) mortality in the USA andother Western countries as an indicator of “how well a country meets the needs of its children” (UNICEF). Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2011, 23, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rees, W.E. Ecological footprints and appropriated carrying capacity: What urban economics leaves out. Environ. Urban. 1992, 4, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, W.; Wackernagel, M. Urban ecological footprints: Why cities cannot be sustainable—and why they are a key to sustainability. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 1996, 16, 223–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, F.; Zachariadis, M. Determinants of Public Health Outcomes: A Macroeconomic Perspective, Computing in Economics and Finance. Soc. Comput. Econ. 2006, 107, 1–29. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/sce/scecfa/107.html (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Spulbar, C.; Ejaz, A.; Birau, R.; Trivedi, J. Sustainable investing based on momentum strategies in emerging stock markets: A case study for Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE) of India. Sci. Ann. Econ. Bus. 2019, 66, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ssozi, J.; Amlani, S. The Effectiveness of Health Expenditure on the Proximate and Ultimate Goals of Healthcare in Sub-Saharan Africa. World Dev. 2015, 76, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, J.M.; Tureeva, N.K. Infant and Child Mortality. In R.o. Ministry of Health, Uzbekistan Health Examination Survey; ORC Macro: Chevy Chase, MD, USA, 2004; p. 390. [Google Scholar]

- The World Bank. World Development Indicators. 2021. Available online: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators# (accessed on 7 April 2021).

- Toan Do, Q.; Joshi, S.; Stolper, S. Can. Environmental Policy Reduce Infant Mortality? Evidence from the Ganga Pollution Cases, Working Paper; International Growth Center (IGC): London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, J.C. Mapping Social Psychology Series. Social Influence; Thomson Brooks/Cole Publishing Co.: Pacific Grove, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs Sustainable Development. 2021. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goal (accessed on 27 April 2021).

- United Nations. World Population Prospects; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Report of The United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED). In The Brundtland Report—“Our Common Future”; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. Children: Reducing Mortality. Media Centre: World Health Organisation. 2021. Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs178/en/ (accessed on 11 January 2021).

- World Wide Fund (WWF). What Is Ecological Footprint? 2021. Available online: https://wwf.panda.org/discover/knowledge_hub/teacher_resources/webfieldtrips/ecological_balance/eco_footprint/? (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Xu, K.; Soucat, A.; Kutzin, J.; Brindley, C.; Maele, N.; Toure, H.; Garcia, M.; Li, D.; Barroy, H.; Saint-Germain, G.; et al. Public Spending on Health: A Closer Look at Global Trends; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yaqub, J.O.; Ojapinwa, T.V.; Yussuff, R.O. Public health expenditure and health outcome in Nigeria: The impact of governance. Eur. Sci. J. 2012, 8, 189–201. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, T.T.; Chang, Y.C. Standing of environmental public-interest litigants in China: Evolution, obstacles and solutions. J. Environ. Law 2019, 30, 369–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).