1. Introduction

CSR is one of the most important concepts of today’s world due to the increasing emphasis on sustainability. Recently, CSR outcomes at the employee level are receiving increasing attention [

1]. The micro-level CSR studies at the employee level have mainly examined how employees make sense of their organization’s CSR activities (CSR perceptions) and what impact CSR sense-making has on their workplace attitudes and behaviors [

2,

3,

4]. CSR perceptions (CSRP) affect employee outcomes, such as organizational commitment [

5], job performance, task performance, organizational citizenship behavior [

6], creativity [

7], employee engagement [

2], turnover, pride, job embeddedness [

8,

9], task performance, psychological safety [

10], and pro-environmental behavior [

11]. Although CSRP positively affects job performance and satisfaction [

12], the relationship between CSRP and Career Satisfaction (CSAT) is still not explored. This is quite surprising as job satisfaction and CSAT are closely related concepts [

13,

14].

There is a rising interest among scholars to examine antecedents of CSAT [

15,

16]. Through CSAT, individual and organizational performance can be enhanced [

15]. Managers are eagerly concerned about the causes of CSAT because organizational success, in the long run, is dependent on how satisfied its members are with their overall careers. Despite having so many benefits, minimal research into antecedents of CSAT is found in the current literature, and more research in this regard is needed [

17]. There are two important gaps in the current literature that this study intends to fill. The first gap is that although employees’ perceptions about their organizations’ CSR positively affect their work outcomes, such as well-being, job satisfaction, life satisfaction, and work engagement [

1,

18], how CSRP relates to CSAT (gratification that one gets from the career in terms of extrinsic as well as intrinsic aspects) is still something that has not been examined empirically in the extant literature. The CSR–CSAT link is worth investigating because how an individual perceives organizational policies related to CSR would influence their long-term orientation towards the career. The second gap is that empirical studies on the effect of perceived CSR on employee behaviors were unable to comprehensively explain the underlying mechanisms and boundary conditions [

9,

19]. Perceptions can cause positive outcomes when employees have cognitive and psychological resources that can help them to maintain positivity. Psychological capital (PsyCap) provides necessary psychological support to an employee that is required to keep them satisfied in their job, career, and life [

20]. A career is usually based on a long-term manifestation of one’s working environment, job, and meaningfulness. There can be ups and downs during a career, and PsyCap would help an employee to remain hopeful, confident, resilient, and optimistic during hard and challenging moments. This is especially relevant in situations where perceptions about organizational actions, policies, and strategies are to be considered. Research has found that an employee’s concept of morality does act as a crucial boundary condition in understanding the impact of their perceptions about organizational policies on behavioral outcomes [

21]. Therefore, this study intends to examine the roles of PsyCap and moral identity in order to better understand the relationship between CSRP and CSAT.

PsyCap refers to a person’s positive psychological state of development. This study contends that the CSR–CSAT link is contingent upon an employee’s cognitive and psychological resources. Having a positive perception that an organization is socially responsible and is contributing genuinely to protecting the environment and uplifting the society promotes a feeling of pride and meaningfulness that one gets from the job and work environment [

22]. It also increases intrinsic motivational and psychological resources to engage in prosocial and extra-role behaviors [

23] and enhances organizational commitment, loyalty, morale, and organizational identification [

24]. Perceived CSR positively influences employees’ psychological and cognitive resources [

20,

25]. A higher level of optimism develops when there is a perception that the organization is ethical and it will defend its employees during an economic crisis or will act reasonably and responsibly in the worst situations. The hope of individuals also increases when they feel that the organization will provide all necessary resources and create a supportive environment to reach personal and organizational goals. Positive CSRP makes employees trust the organization, and they feel psychologically safe [

25] to invest more energy and effort in pursuit of their goals, consequently increasing their motivation, cognitive abilities, and self-efficacy [

26]. Ngo et al. [

27] suggested that employees utilize their PsyCap to attain career success in objective as well as subjective terms. Having positive perceptions of CSR might help an employee to accumulate positive psychological resources such as hope, optimism, self-efficacy, and resilience. This, in turn, helps them to attain fulfillment in the career. Therefore, we can suggest that CSRP has an impact on CSAT and that one possible mediator of this relationship is PsyCap.

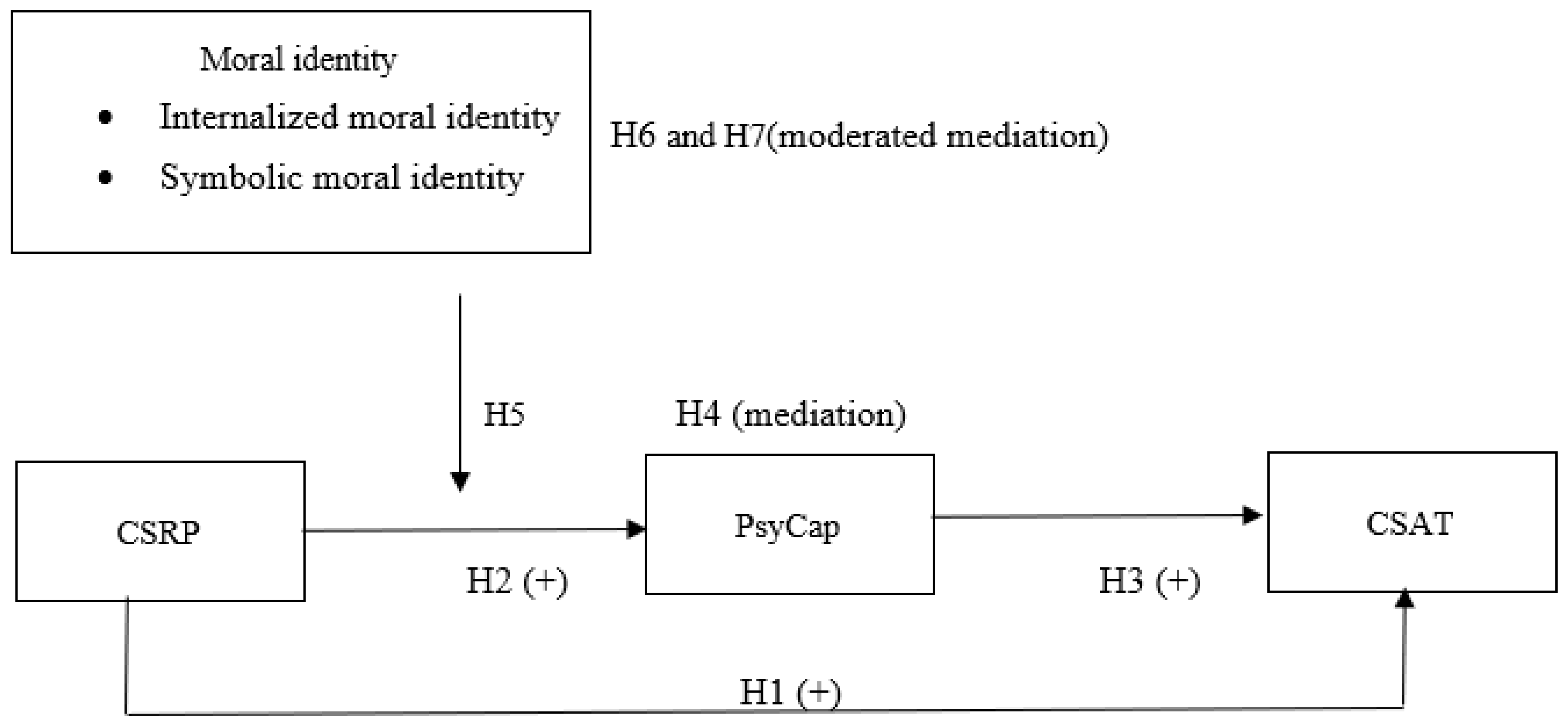

Another objective of our study is to investigate the moderating role of moral identity in the formation process between CSRP, PsyCap, and CSAT. Reactions to CSR can vary based on employees’ morality. Moral identity (MI) refers to the self-concept that one has about values, morality, ethics, and other moral traits [

28]). The moral behavior of an individual depends on how they think about morality, their self-concept about moral values, and the importance that they ascribe to different moral situations. There are differences in the moral identities of individuals. MI is comprised of two dimensions [

28]. The first dimension is Internalized Moral Identity (IMI) which refers to the self-concept that arrays moral traits as private, personal, ideal, internal, and actual self. Symbolic Moral Identity (SMI; self-concept that arrays moral values and traits as public, external, social, and open self) is the second dimension of MI. There is a high level of compatibility between internalized and symbolic dimensions of MI. MI perspective is especially relevant in the context of how an individual perceives organizational policies. For instance, CSR initiatives such as planting trees, arranging seminars to promote environmental awareness, and giving charity to poor people can create positive as well as negative perceptions depending on whether an employee’s MI validates and reinforces these initiatives. If they think that these are real, genuine, and actual efforts to protect the environment and contribute to the betterment of society, the effect of CSR on psychological resources and other outcomes is likely to amplify. MI moderates the effect of perceived CSR on employee behaviors such as job satisfaction and organizational identification [

29], helping behavior [

21], and organizational citizenship behavior [

30]. PsyCap refers to a person’s positive psychological resources embedded in cognitive and emotional states, and it is viewed as dependent on one’s self-concept of moral traits. Therefore, the combination of MI and CSRP tends to increase an employee’s positive psychological resources, i.e., PsyCap. Drawing on social identity theory [

31], we suggest that CSRP and MI (internalized and symbolic) affect PsyCap, and in turn, the CSAT. More specifically, this study suggests that MI (internalized and symbolic) moderates the mediated effect of PsyCap on the CSRP–CSAT link.

Figure 1 presents the research model of this study.

5. Discussion

The primary goal of the current study is to investigate the relationships among CSRP, PsyCap, internalized and SMI, and CSAT. There has been an increasing interest in understanding the effect of employees’ CSRP on various behaviors, attitudes, and outcomes at the individual level [

20,

21]. This study addresses the call to examine the effect of individual psychological resources in the CSR-employee-focused outcomes literature [

74]. There are six major findings to report. First, we found that CSRP positively affects employees’ CSAT. Ilkhanizadeh and Karatepe [

17] found that employees of socially responsible airline companies made positive sense-making of CSR programs, and hence they were more satisfied with their careers. Second, the results show that CSRP increases employees’ PsyCap.

This finding is in line with Mao et al.’s [

40] finding that perceived CSR increases the psychological safety, hope, confidence, and resilience of employees. The third finding is that increase in PsyCap would enhance CSAT. Having positive psychological resources make employees satisfied with their lives, and their work-family conflicts and turnover intentions also reduce considerably [

75]. It is also found in previous studies that PsyCap increases subjective well-being and job satisfaction [

40].

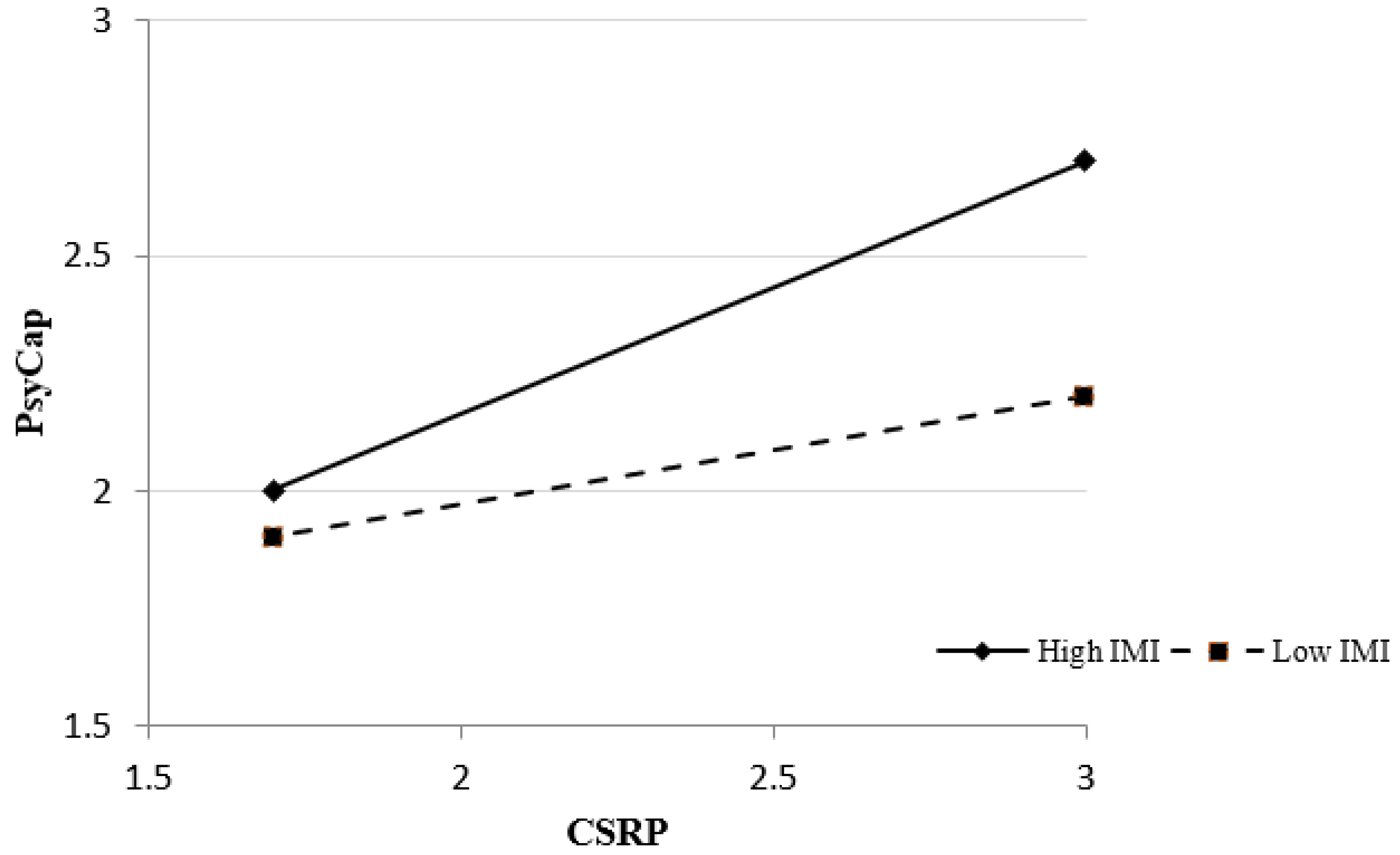

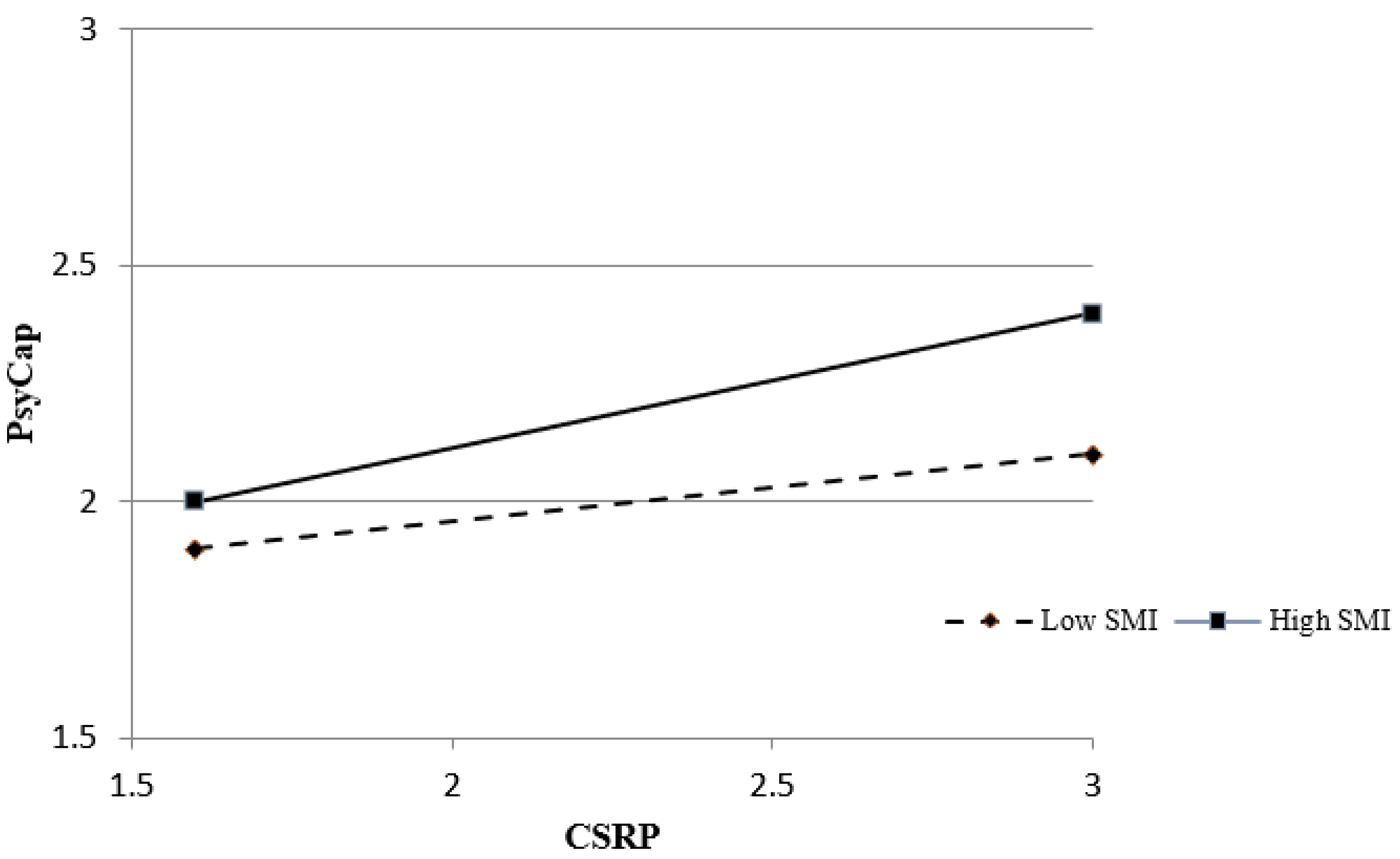

The fourth finding is that PsyCap mediated the effect of CSRP on CSAT. It implies that positive sense-making about an organization’s CSR practices enhances positive psychological resources by giving them more hope, resilience, self-efficacy, and optimism, and these psychological states provide CSAT. As our findings show partial mediation by PsyCap, it suggests that some of the variances in the effect of CSRP on CSAT are explained through PsyCap. Fifth, this study found that internalized and SMI serve as a boundary condition in the CSRP–PsyCap link. The findings indicate that employees who have high levels of IMI and SMI strengthen the relationship between CSRP and PsyCap. It implies that the highest level of PsyCap can be observed among employees who perceive their organizations’ CSR programs as beneficial to the stakeholders and when they have high IMI and SMI. However, when employees have low levels of IMI and SMI, CSRP seems to be more important for enhancing PsyCap. Prior studies [

10,

76] found moderating roles of MI and personality traits on the perceived CSR and PsyCap link. Finally, our findings show that MI moderated the mediated effect of PsyCap on the CSRP–CSAT link. If employees have high IMI and SMI, PsyCap mediates the effect of CSRP on CSAT. Positive sense-making about CSR programs tends to help such employees having more positive psychological resources (hope, self-efficacy, optimism, and resilience) and inducing them to be more satisfied with their careers. This finding is in line with Wang et al.’s [

21] results that confirmed the moderated mediation of MI on the links between perceived CSR, organizational identification, and employee attitudes and behaviors (turnover intentions, in-role performance, and helping behavior).

5.1. Theoretical Implications

This study contributes to theory in the following ways. First, there is a dearth of research on perceived CSR and employee outcomes through intervening psychological mechanisms [

21]. Singhapakdi et al. [

29] suggested that MI of an employee might serve as a boundary condition, and future research should look into the effect of CSRP on employee outcomes. This study filled the gap identified by Singhapakdi et al. [

29] by explaining the moderating role of MI on the CSRP–PsyCap–CSAT links. Second, research into the underlying mechanisms that could explore the micro-CSR literature and psychology of CSR at the employee level is still scarce [

1,

20].

This study contributes to theory in the following ways. First, there is a dearth of research on perceived CSR and employee outcomes through intervening psychological mechanisms [

21]. MI is expected to moderate the relationship between perceived CSR and employee-level attitudes, behaviors, and outcomes [

29]. This study found the moderating role of MI on the CSRP and PsyCap link and hence contributes to the body of knowledge by integrating MI, CSR, and the career literatures. Second, research into the underlying mechanisms that could explore the micro-CSR literature and psychology of CSR at the employee level is still scarce [

1,

20]. This research adds to the CSR literature by investigating the effect of PsyCap and MI. Third, we address the call to further examine the antecedents of CSAT by Jung and Takeuchi [

15], and Ngo and Hui [

16]. Understanding what causes employees to become satisfied with their careers is crucial for HR managers because retaining employees help to achieve success. This study found that when organizational CSR is communicated effectively to employees, positive sense-making might prevail, which in turn motivates employees to stay longer in such organizations and remain committed to their careers. Fourth, the mediating role of PsyCap adds a new mediator in CSR–outcomes relationships. Ilkhanizadeh and Karatepe [

17] tested the mediation of organizational identification in the CSR–CSAT link and suggested that other psychological, motivational, and personality factors could be looked at in future studies. This study contributes to the existing literature by finding that PsyCap mediates the relationship between CSRP and CSAT. Finally, we suggested MI (internalized and symbolic) as individual personal variables to moderate the relationships between employees’ CSRP, PsyCap, and CSAT. Hence, this study contributes to MI research in organizations, which is still in its infancy [

21,

67].

5.2. Practical Implications

Some practical implications that this study offers are as follows. In order to enhance CSAT among employees, organizations should try to initiate CSR programs and communicate these initiatives to their employees. By publicizing CSR actions and programs, the positive sense-making of CSR value among internal stakeholders might increase considerably. To improve MI dimensions, organizations should train employees by frequently communicating statement of values as well as CSR values such as addressing social issues, taking care of social needs, protecting the environment, promoting green behaviors, believing in ethical practices, and promoting honesty, generosity, fairness, and kindness. By doing so, employees would be sensitized to understand the importance of CSR, morality, ethicality, superior values, and honesty. They may try to associate themselves with these values and incorporate them into their self-concepts. Moreover, the PsyCap of employees can be enhanced by introducing interventions. For example, hope can be built by improving goal-setting by breaking complex goals into manageable sizes and celebrating small achievements. To build optimism, organizations should focus on understanding when to tone down employees’ expectations and assist them with more effective goal-setting strategies. Clear planning for tasks and having detailed research might also prove beneficial as employees become confident and can foresee possible outcomes and future. CSR implementation and effective communication, PsyCap interventions, and salient MI training sessions are going to give meaningfulness to employees, and they become more satisfied with their careers.

5.3. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

There are few limitations of the current study. First, the data are cross-sectional. CSRP, MI, PsyCap, and CSAT are subject to change over time. Therefore, future studies should longitudinally collect data on CSRP and PsyCap in particular. Second, data from an Asian country might limit the generalizability of the findings, especially in Western countries. Third, the effect of CSRP on other career-related outcomes should also be investigated in future research. For example, how CSRP affects career adaptability and career development should also be considered. Last, this study did not compare different industries to find out the similarities and differences across the industry in terms of effect sizes. For example, it is likely that employees who are working in the oil and gas sector might attribute different moral reasons to CSR actions than employees working in the hotel industry. Future studies should therefore look for the differences among industries.

5.4. Conclusions

Understanding how employees perceive CSR policies and what effects perceptions create on their CSAT are intriguing for academicians and practitioners. The primary aim of this study was to identify how CSRP influenced CSAT through PsyCap and MI. The data for this study were collected from Saudi Arabia. We found that CSRP positively affected the CSAT and PsyCap mediated CSRP–CSAT relationship. Both dimensions of MI (internalized and symbolic) positively moderated the link between CSRP and PsyCap. The indirect effect of CSRP on CSAT via PsyCap was moderated by IMI and SMI. CSR implementation and effective communication, PsyCap interventions, and salient MI training sessions are going to give meaningfulness to employees, and they become more satisfied with their careers.