A Systematic Literature Review of Sexual Harassment Studies with Text Mining

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What are the main research topics in studies related to sexual harassment?

- What is the temporal trend of each topic?

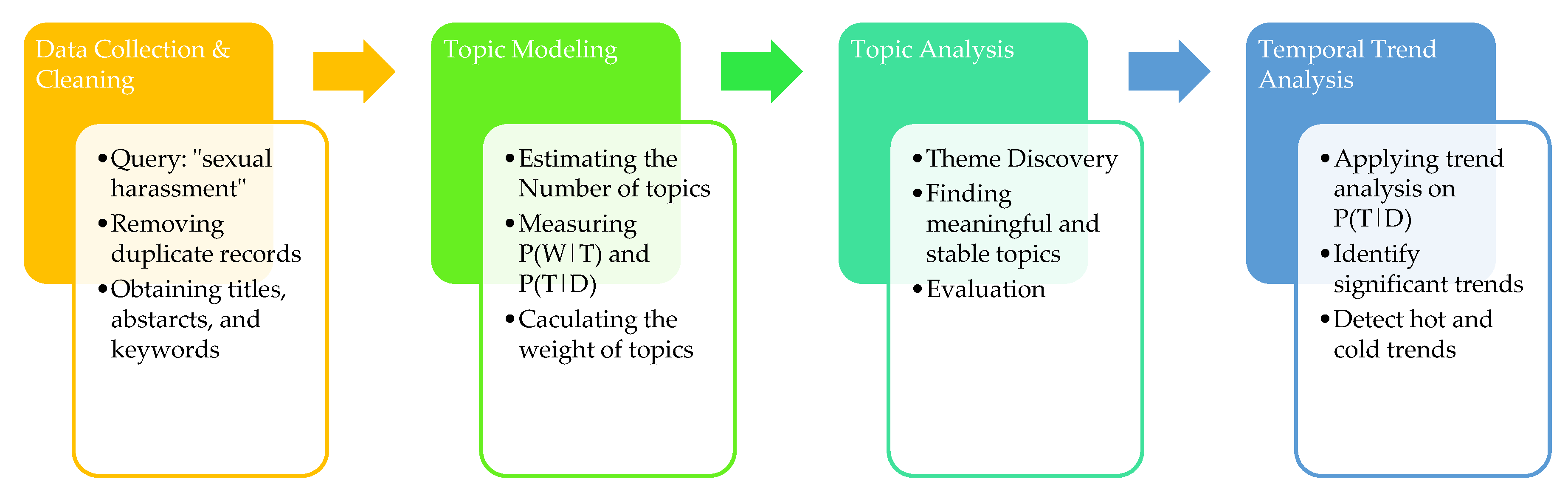

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection and Cleanings

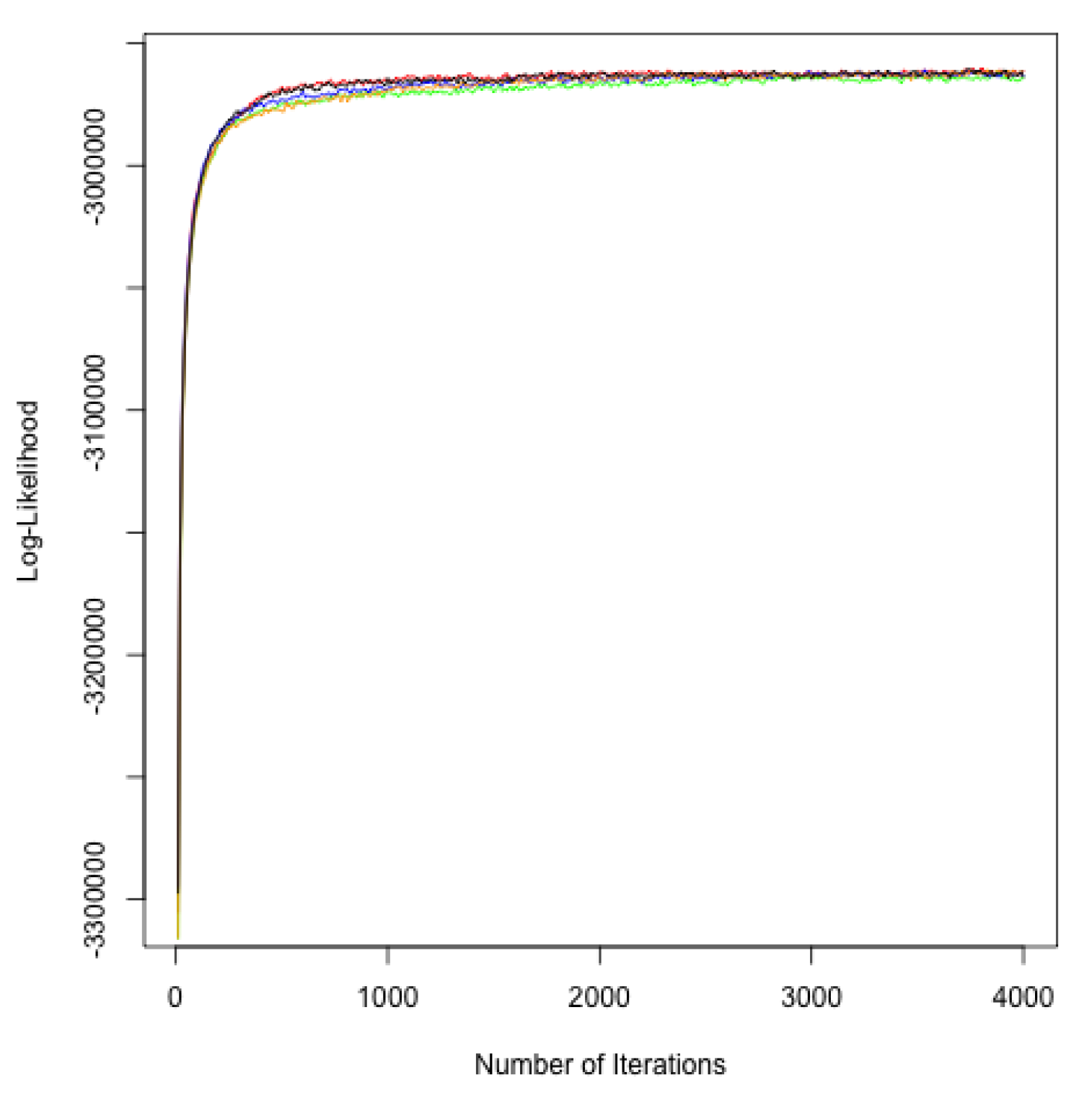

2.2. Topic Modeling

| Topics | Documents | |

| & | ||

| P(Wi|Tk) | P(Tk|Dj) |

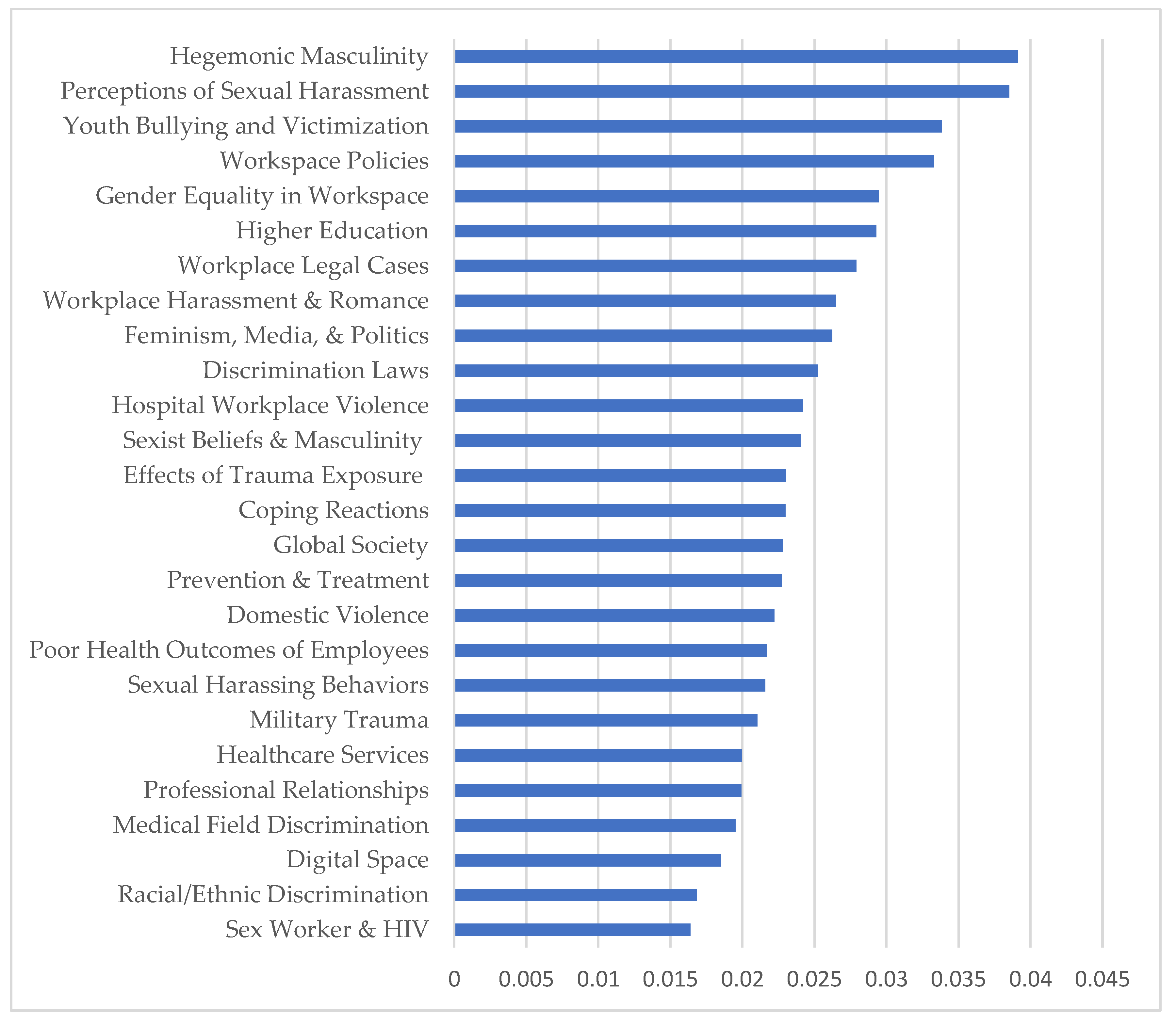

2.3. Topic Analysis

2.4. Temporal Trend Analysis

3. Results

- 1970s: Hospital Workspace Violence, Hegemonic Masculinity, and Gender Equality in Workspace.

- 1980s: Workspace Policies, Perceptions of Sexual Harassment, and Gender Equality in Workspace

- 1990s: Perceptions of Sexual Harassment, Workplace Legal Cases, Workspace Policies

- 2000s: Perceptions of Sexual Harassment, Hegemonic Masculinity, Youth Bullying and Victimization

- 2010s: Youth Bullying and Victimization, Hegemonic Masculinity, Workspace Policies

- 2020: Hegemonic masculinity, feminism, media, and politics, workspace policies.

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| ID | Label | Research Examples | Topic |

|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | Sexual Harassing Behaviors | [97,98,99] | behaviors sexually harassing unwanted offensive potentially language nature form aggressive |

| T2 | Higher Education | [100,101,102] | students education university college faculty school schools teachers academic educational |

| T4 | Hegemonic Masculinity | [103,104,105] | experiences sexuality power gendered ways masculinity culture gay identity argue |

| T6 | Professional Relationships | [106,107,108] | ethics professional relationships ethical practice misconduct moral issues management sexuality |

| T7 | Sex Workers and HIV | [109,110,111] | sex young hiv risk south human africa health workers education |

| T12 | Perceptions of Sexual Harassment | [112,113,114] | perceptions differences victim behavior target effects sex scenarios perpetrator found |

| T13 | Workplace Harassment and Romance | [115,116,117] | workplace organizational work organizations employees power incivility management impact romance |

| T14 | Workplace Legal Cases | [118,119,120] | legal law environment court hostile discrimination decisions rights act claims |

| T16 | Gender Equality in Workspace | [121,122,123] | discrimination sex career role equal leadership development differences employment work |

| T17 | Discrimination Laws | [124,125,126] | states united rights law human countries policy education public employment |

| T18 | Domestic Violence | [127,128,129] | violence partner physical dating abuse intimate assault victims ipv domestic |

| T19 | Military Trauma | [130,131,132] | military veterans assault personnel service mst trauma health war stress |

| T20 | Poor Health Outcomes of Employees | [133,134,135] | workplace occupational bullying workers job health environment stress employment psychosocial |

| T21 | Medical Field Discrimination | [136,137,138] | medical physicians training medicine practice discrimination residents education patients surgery |

| T22 | Racial/Ethnic Discrimination | [139,140,141] | discrimination race white black ethnic african minority diversity group hispanic |

| T23 | Digital Space | [142,143,144] | online internet social media computer video youth pornography web game |

| T24 | Prevention and Treatment | [145,146,147] | training prevention intervention control group program attitudes knowledge programs effective |

| T25 | Feminism, Media, and Politics | [148,149,150] | feminist media political politics movement public activism work social mass |

| T26 | Workspace Policies | [151,152,153] | policy public training organizations procedures prevention response problem reporting awareness |

| T28 | Sexist Beliefs and Masculinity | [154,155,156] | sexism social attitudes sexist identity beliefs hostile stereotypes acceptance psychology |

| T31 | Hospital Workplace Violence | [157,158,159] | violence workplace nurses hospital verbal health patients staff physical care |

| T33 | Healthcare Services | [160,161,162] | health care mental services medical service treatment quality home substance |

| T34 | Global Society | [163,164,165] | social india status cultural public economic countries life rights conditions |

| T36 | Effects of Trauma Exposure | [166,167,168] | disorder symptoms stress mental depression ptsd posttraumatic trauma physical pain |

| T37 | Coping Reactions | [169,170,171] | coping responses negative fear strategies experience social anger self-esteem emotional |

| T40 | Youth Bullying and Victimization | [172,173,174] | school victimization girls bullying students peer boys high secondary middle |

References

- McDonald, P. Workplace sexual harassment 30 years on: A review of the literature. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2012, 14, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harassment, S.S. The Facts behind the# MeToo Movement: A National Study on Sexual Harassment and Assault. Available online: http://www.stopstreetharassment.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Full-Report-2018-National-Study-on-Sexual-Harassment-and-Assault.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- Scope of the Problem: Statistics|RAINN. Available online: https://www.rainn.org/statistics/scope-problem (accessed on 13 August 2020).

- Victims of Sexual Violence: Statistics|RAINN. Available online: https://www.rainn.org/statistics/victims-sexual-violence (accessed on 13 August 2020).

- Statistics. National Sexual Violence Resource Center [Internet]. Available online: https://www.nsvrc.org/statistics (accessed on 13 August 2020).

- Barak, A. Sexual harassment on the Internet. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2005, 23, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, A.; Swan, S.; Moraes, M.F. Space identification of sexual harassment reports with text mining. Proc. Assoc. Inform. Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, e265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, C.; DeGue, S.; Florence, C.; Lokey, C.N. Lifetime economic burden of rape among US adults. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 52, 691–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Martín, A.; Orduna-Malea, E.; Thelwall, M.; López-Cózar, E.D. Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Scopus: A systematic comparison of citations in 252 subject categories. J. Informetr. 2018, 12, 1160–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studd, M.V.; Gattiker, U.E. The evolutionary psychology of sexual harassment in organizations. Ethol. Sociobiol. 1991, 12, 249–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maypole, D.E.; Skaine, R. Sexual harassment in the workplace. Soc. Work 1983, 28, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maypole, D.E. Sexual harassment at work: A review of research and theory. Affilia 1987, 2, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, L.F.; Shullman, S.L. Sexual harassment: A research analysis and agenda for the 1990s. J. Vocat. Behav. 1993, 42, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutek, B.A.; Koss, M.P. Changed women and changed organizations: Consequences of and coping with sexual harassment. J. Vocat. Behav. 1993, 42, 28–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charney, D.A.; Russell, R.C. An overview of sexual harassment. Am. J. Psychiatry 1994, 151, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, P.A.; Cochran, C.C.; Olson, A.M. Social science research on lay definitions of sexual harassment. J. Soc. Issues 1995, 51, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, L.F.; Swan, S.; Fischer, K. Why didn’t she just report him? The psychological and legal implications of women’s responses to sexual harassment. J. Soc. Issues 1995, 51, 117–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nora, L.M. Sexual harassment in medical education: A review of the literature with comments from the law. Acad. Med. 1996, 71, S113–S118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, M.J.; Andrew, J.D. Sexual harassment: The law. J. Rehabil. Adm. 1997, 21, 23–42. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donohue, W.; Downs, K.; Yeater, E.A. Sexual harassment: A review of the literature. Aggress. Violent Behav. 1998, 3, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenthal, J.A. The reasonable woman standard: A meta-analytic review of gender differences in perceptions of sexual harassment. Law Hum. Behav. 1998, 22, 33–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welsh, S. Gender and sexual harassment. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1999, 25, 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sev’er, A. Sexual harassment: Where we were, where we are and prospects for the new millennium introduction to the special issue. Can. Rev. Sociol./Rev. Can. Sociol. 1999, 36, 469–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmerman, G.; Bajema, C. Incidence and Methodology in Sexual Harassment Research in Northwest Europe. Womens Stud. Int. Forum 1999, 22, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sbraga, T.P.; O’donohue, W. Sexual harassment. Annu. Rev. Sex Res. 2000, 11, 258–285. [Google Scholar]

- Einarsen, S. Harassment and bullying at work: A review of the Scandinavian approach. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2000, 5, 379–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotundo, M.; Nguyen, D.-H.; Sackett, P.R. A meta-analytic review of gender differences in perceptions of sexual harassment. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilies, R.; Hauserman, N.; Schwochau, S.; Stibal, J. Reported incidence rates of work-related sexual harassment in the United States: Using meta-analysis to explain reported rate disparities. Pers. Psychol. 2003, 56, 607–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banyard, V.L.; Plante, E.G.; Moynihan, M.M. Bystander education: Bringing a broader community perspective to sexual violence prevention. J. Community Psychol. 2004, 32, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q. Gender and CMC: A review on conflict and harassment. Aust. J. Educ. Technol. 2005, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyllensten, K.; Palmer, S. The role of gender in workplace stress: A critical literature review. Health Educ. J. 2005, 64, 271–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigal, J. International sexual harassment. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006, 1087, 356–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldzweig, C.L.; Balekian, T.M.; Rolon, C.; Yano, E.M.; Shekelle, P.G. The state of women veterans’ health research: Results of a systematic literature review. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2006, 21, S82–S92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willness, C.R.; Steel, P.; Lee, K. A meta-analysis of the antecedents and consequences of workplace sexual harassment. Pers. Psychol. 2007, 60, 127–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagil, D. When the customer is wrong: A review of research on aggression and sexual harassment in service encounters. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2008, 13, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D.K.; Chow, S.Y.; Lam, C.B.; Cheung, S.F. Examining the job-related, psychological, and physical outcomes of workplace sexual harassment: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Women Q. 2008, 32, 362–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary-Kelly, A.M.; Bowes-Sperry, L.; Bates, C.A.; Lean, E.R. Sexual harassment at work: A decade (plus) of progress. J. Manag. 2009, 35, 503–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, C.M.; Davidson, M.J.; Fielden, S.L.; Hoel, H. Reviewing sexual harassment in the workplace—An intervention model. Pers. Rev. 2010, 39, 655–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, C.A.; Monda-Amaya, L.E.; Espelage, D.L. Bullying perpetration and victimization in special education: A review of the literature. Remedial Spec. Educ. 2011, 32, 114–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockdale, M.S.; Nadler, J.T. Situating sexual harassment in the broader context of interpersonal violence: Research, theory, and policy implications. Soc. Issues Policy Rev. 2012, 6, 148–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pina, A.; Gannon, T.A. An overview of the literature on antecedents, perceptions and behavioural consequences of sexual harassment. J. Sex. Aggress. 2012, 18, 209–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, N.E. Rethinking adolescent peer sexual harassment: Contributions of feminist theory. J. Sch. Violence 2013, 12, 340–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okechukwu, C.A.; Souza, K.; Davis, K.D.; De Castro, A.B. Discrimination, harassment, abuse, and bullying in the workplace: Contribution of workplace injustice to occupational health disparities. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2014, 57, 573–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P.E.; Zhou, Z.E.; Che, X.X. Nurse exposure to physical and nonphysical violence, bullying, and sexual harassment: A quantitative review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2014, 51, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roehling, M.V.; Huang, J. Sexual harassment training effectiveness: An interdisciplinary review and call for research. J. Organ. Behav. 2018, 39, 134–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stander, V.A.; Thomsen, C.J. Sexual harassment and assault in the US military: A review of policy and research trends. Mil. Med. 2016, 181, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakur, M.B.; Paul, P. Sexual Harassment in Academic Institutions: A Conceptual Review. J. Psychosoc. Res. 2017, 12, 33. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, N.; Powell, A. Technology-facilitated sexual violence: A literature review of empirical research. Trauma Violence Abuse 2018, 19, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzgerald, L.F.; Cortina, L.M. Sexual Harassment in Work Organizations: A View from the 21st Century. In APA handbook of the Psychology of Women: Perspectives on Women’s Private and Public Lives; Travis, C.B., White, J.W., Rutherford, A., Williams, W.S., Cook, S.L., Wyche, K.F., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; pp. 215–234. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, L.B.; Martin, S.L. Sexual harassment of college and university students: A systematic review. Trauma Violence Abuse 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenbrunsel, A.E.; Rees, M.R.; Diekmann, K.A. Sexual harassment in academia: Ethical climates and bounded ethicality. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2019, 70, 245–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minnotte, K.L.; Legerski, E.M. Sexual harassment in contemporary workplaces: Contextualizing structural vulnerabilities. Sociol. Compass 2019, 13, e12755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draucker, C.B. Responses of Nurses and Other Healthcare Workers to Sexual Harassment in the Workplace. OJIN Online J. Issues Nurs. 2019, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehman, A.C.; Gross, A.M. Sexual cyberbullying: Review, critique, & future directions. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2019, 44, 80–87. [Google Scholar]

- Burn, S.M. The psychology of sexual harassment. Teach. Psychol. 2019, 46, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siuta, R.L.; Bergman, M.E. Sexual harassment in the workplace. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Business and Management; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Araujo J de, O.; Souza FM de Proença, R.; Bastos, M.L.; Trajman, A.; Faerstein, E. Prevalence of sexual violence among refugees: A systematic review. Rev. Saude Publica 2019, 53, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondestam, F.; Lundqvist, M. Sexual harassment in higher education—A systematic review. Eur. J. High. Educ. 2020, 10, 397–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahsay, W.G.; Negarandeh, R.; Nayeri, N.D.; Hasanpour, M. Sexual harassment against female nurses: A systematic review. BMC Nurs. 2020, 19, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, H.; Loukaitou-Sideris, A.; Agrawal, A.W. Sexual harassment and assault in transit environments: A review of the English-language literature. J. Plan. Lit. 2020, 35, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.S.; Biefeld, S.D.; Elpers, N. A bioecological theory of sexual harassment of girls: Research synthesis and proposed model. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2020, 24, 299–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methley, A.M.; Campbell, S.; Chew-Graham, C.; McNally, R.; Cheraghi-Sohi, S. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: A comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meho, L.I.; Yang, K. Impact of data sources on citation counts and rankings of LIS faculty: Web of Science versus Scopus and Google Scholar. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2007, 58, 2105–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westergaard, D.; Stærfeldt, H.-H.; Tønsberg, C.; Jensen, L.J.; Brunak, S. A comprehensive and quantitative comparison of text-mining in 15 million full-text articles versus their corresponding abstracts. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2018, 14, e1005962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleuren, W.W.; Alkema, W. Application of text mining in the biomedical domain. Methods 2015, 74, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blei, D.M.; Ng, A.Y.; Jordan, M.I. Latent dirichlet allocation. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2003, 3, 993–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Karami, A. Fuzzy Topic Modeling for Medical Corpora. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Maryland, Baltimore County, MD, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Karami, A.; Bennett, L.S.; He, X. Mining public opinion about economic issues: Twitter and the us presidential election. Int. J. Strateg. Decis. Sci. (IJSDS) 2018, 9, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, A.; Shaw, G. An exploratory study of (#) exercise in the Twittersphere. In Proceedings of the iConference 2019 Proceedings, Washington, DC, USA, 31 March–3 April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Karami, A.; Webb, F. Analyzing health tweets of LGB and transgender individuals. Proc. Assoc. Inform. Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, e264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, A.; Elkouri, A. Political Popularity Analysis in Social Media. In International Conference on Information; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 456–465. [Google Scholar]

- Karami, A.; Kadari, R.R.; Panati, L.; Nooli, S.P.; Bheemreddy, H.; Bozorgi, P. Analysis of Geotagging Behavior: Do Geotagged Users Represent the Twitter Population? ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, A.; Lundy, M.; Webb, F.; Turner-McGrievy, G.; McKeever, B.W.; McKeever, R. Identifying and Analyzing Health-Related Themes in Disinformation Shared by Conservative and Liberal Russian Trolls on Twitter. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Money, V.; Karami, A.; Turner-McGrievy, B.; Kharrazi, H. Seasonal characterization of diet discussions on Reddit. Proc. Assoc. Inform. Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, e320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, A.; Anderson, M. Social media and COVID-19, Characterizing anti-quarantine comments on Twitter. Proc. Assoc. Inform. Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, e349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemsley, J.; Erickson, I.; Jarrahi, M.H.; Karami, A. Digital nomads, coworking, and other expressions of mobile work on Twitter. First Monday 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, A.; Dahl, A.A.; Shaw, G.; Valappil, S.P.; Turner-McGrievy, G.; Kharrazi, H.; Bozorgi, P. Analysis of Social Media Discussions on (#)Diet by Blue, Red, and Swing States in the U.S. Healthcare 2021, 9, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karami, A.; Lundy, M.; Webb, F.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Twitter and research: A systematic literature review through text mining. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 67698–67717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, E.; Karami, A. Exploring research trends in big data across disciplines: A text mining analysis. J. Inform. Sci. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, A.; Ghasemi, M.; Sen, S.; Moraes, M.F.; Shah, V. Exploring diseases and syndromes in neurology case reports from 1955 to 2017 with text mining. Comput. Biol. Med. 2019, 109, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, A.; Bookstaver, B.; Nolan, M.; Bozorgi, P. Investigating diseases and chemicals in COVID-19 literature with text mining. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 2021, 1, 100016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, G.; Jarrahi, M.H.; Fei, Y.; Karami, A.; Gafinowitz, N.; Byun, A.; Lu, X. Wearable Activity Trackers, Accuracy, Adoption, Acceptance and Health Impact: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Biomed. Inform. 2019, 93, 103153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, A.; White, C.N.; Ford, K.; Swan, S.; Spinel, M.Y. Unwanted advances in higher education: Uncovering sexual harassment experiences in academia with text mining. Inf. Process. Manag. 2020, 57, 102167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, A.; Swan, S.C.; White, C.N.; Ford, K. Hidden in plain sight for too long: Using text mining techniques to shine a light on workplace sexism and sexual harassment. Psychol. Violence 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, B.H.; Valdez, C.E.; Lilly, M.M. Making meaning out of interpersonal victimization: The narratives of IPV survivors. Violence Against Women 2015, 21, 1065–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altman, D.G. Practical Statistics for Medical Research; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Röder, M.; Both, A.; Hinneburg, A. Exploring the space of topic coherence measures. In Proceedings of the Eighth ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, Shanghai, China, 2–6 February 2015; pp. 399–408. [Google Scholar]

- Rehurek, R.; Sojka, P. Software framework for topic modelling with large corpora. In Proceedings of the LREC 2010 Workshop on New Challenges for NLP Frameworks, Valletta, Malta, 22 May 2010. [Google Scholar]

- McCallum, A.K. MALLET: A Machine Learning for Language Toolkit. 2002. Available online: http://mallet.cs.umass.edu/ (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- Cortina, L.M.; Berdahl, J.L. Sexual harassment in organizations: A decade of research in review. Handb. Organ. Behav. 2008, 1, 469–497. [Google Scholar]

- Black, A.E.; Allen, J.L. Tracing the legacy of Anita Hill: The Thomas/Hill hearings and media coverage of sexual harassment. Gend. Issues 2001, 19, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allanson, P.B.; Lester, R.R.; Notar, C.E. A history of bullying. Int. J. Educ. Soc. Sci. 2015, 2, 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Chawla, N.; Gabriel, A.S.; O’Leary Kelly, A.; Rosen, C.C. From #MeToo to #TimesUp: Identifying Next Steps in Sexual Harassment Research in the Organizational Sciences; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey Weinstein Timeline: How the Scandal Unfolded—BBC News. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-41594672 (accessed on 18 March 2021).

- Elsesser, K. Covid’s Impact On Sexual Harassment. In: Forbes [Internet]. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/kimelsesser/2020/12/21/covids-impact-on-sexual-harassment/ (accessed on 18 March 2021).

- Smith, S.G.; Basile, K.C.; Gilbert, L.K.; Merrick, M.T.; Patel, N.; Walling, M.; Jain, A. National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010–2012 State Report; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Atlanta, GA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Workman, J.E.; Johnson, K.K. The role of cosmetics in attributions about sexual harassment. Sex Roles 1991, 24, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gervasio, A.H.; Ruckdeschel, K. College Students’ judgments of verbal sexual harassment 1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 22, 190–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrance, C.; Logan, A.; Peters, D. Perceptions of peer sexual harassment among high school students. Sex Roles 2004, 51, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, O. Awareness instruction for sexual harassment: Findings from an experiential learning process at a higher education institute in Israel. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2006, 30, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rester, C.H.; Edwards, R. Effects of sex and setting on students’ interpretation of teachers’ excessive use of immediacy. Commun. Educ. 2007, 56, 34–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampman, C.; Crew, E.C.; Lowery, S.D.; Tompkins, K. Women faculty distressed: Descriptions and consequences of academic contrapower harassment. NASPA J. Women High. Educ. 2016, 9, 169–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D. Hegemonic masculinity and male feminisation: The sexual harassment of men at work. J. Gend. Stud. 2000, 9, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armato, M. Wolves in sheep’s clothing: Men’s enlightened sexism & hegemonic masculinity in academia. Womens Stud. 2013, 42, 578–598. [Google Scholar]

- Grazian, D. The girl hunt: Urban nightlife and the performance of masculinity as collective activity. Symb. Interact. 2007, 30, 221–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, A.E. Challenges in cross-gender mentoring relationships: Psychological intimacy, myths, rumours, innuendoes and sexual harassment. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 1996, 58, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrabee, M.J.; Miller, G.M. An examination of sexual intimacy in supervision. Clin. Superv. 1994, 11, 103–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, J.; Weerakoon, P.; Heard, R. Inappropriate client sexual behaviour in occupational therapy. Occup. Ther. Int. 1999, 6, 176–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chariyeva, Z.; Colaco, R.; Maman, S. HIV risk perceptions, knowledge and behaviours among female sex workers in two cities in Turkmenistan. Glob. Public Health 2011, 6, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, L.; Grenfell, P.; Bonell, C.; Creighton, S.; Wellings, K.; Parry, J.; Rhodes, T. Risk of sexually transmitted infections and violence among indoor-working female sex workers in London: The effect of migration from Eastern Europe. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2011, 87, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agha, S.; Chulu Nchima, M. Life-circumstances, working conditions and HIV risk among street and nightclub-based sex workers in Lusaka, Zambia. Cult. Health Sex. 2004, 6, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menon, S.A.; Kanekar, S. Attitudes Toward Sexual Harassment of Women in India 1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 22, 1940–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine-French, S.; Radtke, H.L. Attributions of responsibility for an incident of sexual harassment in a university setting. Sex Roles 1989, 21, 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.S.; Remland, M.S. Sources of variability in perceptions of and responses to sexual harassment. Sex Roles 1992, 27, 121–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvaggio, A.N.; Streich, M.; Hopper, J.E.; Pierce, C.A. Why Do Fools Fall in Love (at Work)? Factors Associated With the Incidence of Workplace Romance 1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 41, 906–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mano, R.; Gabriel, Y. Workplace romances in cold and hot organizational climates: The experience of Israel and Taiwan. Hum. Relat. 2006, 59, 7–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, C.A.; Karl, K.A.; Brey, E.T. Role of workplace romance policies and procedures on job pursuit intentions. J. Manag. Psychol. 2012, 27, 237–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutek, B.A.; O’Connor, M.A.; Melancon, R.; Stockdale, M.S.; Geer, T.M.; Done, R.S. The utility of the reasonable woman legal standard in hostile environment sexual harassment cases: A multimethod, multistudy examination. Psychol. Public Policy Law 1999, 5, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovera, M.B.; Cass, S.A. Compelled mental health examinations, liability decisions, and damage awards in sexual harrassment cases: Issues for jury research. Psychol. Public Policy Law 2002, 8, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwyn, D.; Wagner, P.; Gilman, G. Trying to make sense of sexual harassment law after Oncale, Holman, and Rene. Cornell Hotel Restaur. Adm. Q. 2004, 45, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzsimmons, T.W.; Callan, V.J. Applying a capital perspective to explain continued gender inequality in the C-suite. Leadersh. Q. 2016, 27, 354–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergamaschi, M. Equal Opportunities and Collective Bargaining in Italy: The Role of Women. Eur. J. Womens Stud. 1999, 6, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutek, B.A.; Cohen, A.G. Sex ratios, sex role spillover, and sex at work: A comparison of men’s and women’s experiences. Hum. Relat. 1987, 40, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, G.B.; Benavides-Espinoza, C. A trend analysis of sexual harassment claims: 1992–2006. Psychol. Rep. 2008, 103, 779–782. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Williams, C. Sexual harassment and human rights law in New Zealand. J. Hum. Rights 2003, 2, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saguy, A. National specificity in an age of globalization: Sexual harassment law in France1. Contemp. Fr. Francoph. Stud. 2004, 8, 425–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab-Reese, L.M.; Peek-Asa, C.; Parker, E. Associations of financial stressors and physical intimate partner violence perpetration. Inj. Epidemiol. 2016, 3, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicario-Molina, I.; Orgaz Baz, B.; Fuertes Martín, A.; González Ortega, E.; Martínez Álvarez, J. Dating violence among youth couples: Dyadic analysis of the prevalence and agreement. Span. J. Psychol. 2015, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phiri-Alleman, W.; Alleman, J.B. Sexual violence in relationships: Implications for multicultural counseling. Fam. J. 2008, 16, 155–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, S.K.; Kimerling, R.E.; Pavao, J.; McCutcheon, S.J.; Batten, S.V.; Dursa, E.; Schneiderman, A.I. Military sexual trauma among recent veterans: Correlates of sexual assault and sexual harassment. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2016, 50, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeardMann, C.A.; Pietrucha, A.; Magruder, K.M.; Smith, B.; Murdoch, M.; Jacobson, I.G.; Millennium Cohort Study Team. Combat deployment is associated with sexual harassment or sexual assault in a large, female military cohort. Womens Health Issues 2013, 23, e215–e223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Dalager, N.; Mahan, C.; Ishii, E. The role of sexual assault on the risk of PTSD among Gulf War veterans. Ann. Epidemiol. 2005, 15, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keuskamp, D.; Ziersch, A.M.; Baum, F.E.; LaMontagne, A.D. Workplace bullying a risk for permanent employees. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2012, 36, 116–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niedhammer, I.; Chastang, J.-F.; Sultan-Taïeb, H.; Vermeylen, G.; Parent-Thirion, A. Psychosocial work factors and sickness absence in 31 countries in Europe. Eur. J. Public Health 2013, 23, 622–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabe-Nielsen, K.; Grynderup, M.B.; Lange, T.; Andersen, J.H.; Bonde, J.P.; Conway, P.M.; Hansen, A.M. The role of poor sleep in the relation between workplace bullying/unwanted sexual attention and long-term sickness absence. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2016, 89, 967–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruce, A.N.; Battista, A.; Plankey, M.W.; Johnson, L.B.; Marshall, M.B. Perceptions of gender-based discrimination during surgical training and practice. Med. Educ. Online 2015, 20, 25923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haviland, M.G.; Yamagata, H.; Werner, L.S.; Zhang, K.; Dial, T.H.; Sonne, J.L. Student mistreatment in medical school and planning a career in academic medicine. Teach. Learn. Med. 2011, 23, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nora, L.M.; McLaughlin, M.A.; Fosson, S.E.; Stratton, T.D.; Murphy-Spencer, A.; Fincher, R.-M.E.; Witzke, D.B. Gender discrimination and sexual harassment in medical education: Perspectives gained by a 14-school study. Acad. Med. 2002, 77, 1226–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bucchianeri, M.M.; Eisenberg, M.E.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Weightism, racism, classism, and sexism: Shared forms of harassment in adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2013, 53, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, M.E.; Palmieri, P.A.; Drasgow, F.; Ormerod, A.J. Racial and ethnic harassment and discrimination: In the eye of the beholder? J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2007, 12, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenfeld, P.; Newell, C.E.; Le, S. Equal opportunity climate of women and minorities in the Navy: Results from the Navy equal opportunity/sexual harassment (NEOSH) survey. Mil. Psychol. 1998, 10, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, K.J.; Wolak, J.; Finkelhor, D. Are blogs putting youth at risk for online sexual solicitation or harassment? Child Abus. Negl. 2008, 32, 277–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, J.; Tang, W.Y. Sexism in online video games: The role of conformity to masculine norms and social dominance orientation. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 33, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, J.; Cruz, C.; Lee, J.Y. Perpetuating online sexism offline: Anonymity, interactivity, and the effects of sexist hashtags on social media. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 52, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yom, Y.-H.; Eun, L. Effects of a CD-ROM educational program on sexual knowledge and attitude. CIN Comput. Inform. Nurs. 2005, 23, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawadzki, M.J.; Danube, C.L.; Shields, S.A. How to talk about gender inequity in the workplace: Using WAGES as an experiential learning tool to reduce reactance and promote self-efficacy. Sex Roles 2012, 67, 605–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, B.G.; Stein, N.D.; Mumford, E.A.; Woods, D. Shifting boundaries: An experimental evaluation of a dating violence prevention program in middle schools. Prev. Sci. 2013, 14, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barger, L.C. Backlash: From Nine to Five to The Devil Wears Prada. Womens Stud. 2011, 40, 336–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asenas, J.; Abram, S. Flattening the past: How news media undermine the political potential of Anita Hill’s story. Fem. Media Stud. 2018, 18, 497–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorour, M.K.; Lal Dey, B. Energising the political movements in developing countries: The role of social media. Cap. Cl. 2014, 38, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese, L.A.; Lindenberg, K.E. The importance of training on sexual harassment policy outcomes. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2003, 23, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peirce, E.R.; Rosen, B.; Hiller, T.B. Breaking the silence: Creating user-friendly sexual harassment policies. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 1997, 10, 225–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese, L.A.; Lindenberg, K.E. Victimhood” and the Implementation of Sexual Harassment Policy. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 1997, 17, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Laux, S.H.; Ksenofontov, I.; Becker, J.C. Explicit but not implicit sexist beliefs predict benevolent and hostile sexist behavior. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 45, 702–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, B.L.; Trigg, K.Y. Tolerance of sexual harassment: An examination of gender differences, ambivalent sexism, social dominance, and gender roles. Sex Roles 2004, 50, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakallı-Uğurlu, N.; Salman, S.; Turgut, S. Predictors of Turkish women’s and men’s attitudes toward sexual harassment: Ambivalent sexism, and ambivalence toward men. Sex Roles 2010, 63, 871–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, K.; Suehiro, Y. Violence chain surrounding patient-to-staff violence in Japanese hospitals. Arch. Environ. Occup. Health 2014, 69, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, C.-Y.; Chiou, S.-T.; Chien, L.-Y.; Huang, N. Workplace violence against nurses–prevalence and association with hospital organizational characteristics and health-promotion efforts: Cross-sectional study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016, 56, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gates, D.M.; Ross, C.S.; McQueen, L. Violence against emergency department workers. J. Emerg. Med. 2006, 31, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosenko, K.A.; Nelson, E.A. Identifying and ameliorating lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health disparities in the criminal justice system. Am. J. Public Health 2018, 108, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh-Hohnbaum, A.-L.T.; Damron-Rodriguez, J.; Washington, D.L.; Villa, V.; Harada, N. Exploring the diversity of women veterans’ identity to improve the delivery of veterans’ health services. Affilia 2003, 18, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haviland, M.J.; Shrestha, A.; Decker, M.R.; Kohrt, B.A.; Kafle, H.M.; Lohani, S.; Surkan, P.J. Barriers to sexual and reproductive health care among widows in Nepal. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2014, 125, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nallari, A. “All we want are toilets inside our homes!” The critical role of sanitation in the lives of urban poor adolescent girls in Bengaluru, India. Environ. Urban. 2015, 27, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackle, S. Safe Spaces: As the Syrian crisis forces women to fend for themselves, female refugees in Jordan are learning to cope. World Policy J. 2018, 35, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, K.; Rahman, M.H. Women in natural disasters: A case study from southern coastal region of Bangladesh. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2014, 8, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curry, J.F.; Aubuchon-Endsley, N.; Brancu, M.; Runnals, J.J.; Workgroup, R.; Workgroup, V.M.-A.M.R.; Fairbank, J.A. Lifetime major depression and comorbid disorders among current-era women veterans. J. Affect. Disord. 2014, 152, 434–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badour, C.L.; Feldner, M.T.; Babson, K.A.; Blumenthal, H.; Dutton, C.E. Disgust, mental contamination, and posttraumatic stress: Unique relations following sexual versus non-sexual assault. J. Anxiety Disord. 2013, 27, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elklit, A.; Christiansen, D.M. ASD and PTSD in rape victims. J. Interpers. Violence 2010, 25, 1470–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magley, V.J. Coping with sexual harassment: Reconceptualizing women’s resistance. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 83, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, K.T.; Tomaka, J.; Palacios, R. Women’s Cognitive, Affective, and Physiological Reactions to a Male Coworker’s Sexist Behavior 1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 31, 1995–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diekmann, K.A.; Walker, S.D.S.; Galinsky, A.D.; Tenbrunsel, A.E. Double victimization in the workplace: Why observers condemn passive victims of sexual harassment. Organ. Sci. 2013, 24, 614–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espelage, D.L.; Basile, K.C.; De La Rue, L.; Hamburger, M.E. Longitudinal associations among bullying, homophobic teasing, and sexual violence perpetration among middle school students. J. Interpers. Violence 2015, 30, 2541–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, T.; Connolly, J.; Pepler, D.; Craig, W. Questioning and sexual minority adolescents: High school experiences of bullying, sexual harassment and physical abuse. Can. J. Community Ment. Health 2009, 22, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espelage, D.L.; Basile, K.C.; Hamburger, M.E. Bullying perpetration and subsequent sexual violence perpetration among middle school students. J. Adolesc. Health 2012, 50, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Time Frame | #Reviewed Studies | Topic | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1983 | N/A | 28 | Sexual harassment at work | [11] |

| 1987 | N/A | 6 | Sexual harassment at work | [12] |

| 1991 | N/A | N/A-68 | Sexual harassment at work | [10] |

| 1993 | N/A | N/A-81 | Sexual harassment at work | [13] |

| 1993 | N/A | N/A-67 | Sexual harassment at work | [14] |

| 1994 | N/A | N/A-58 | Sexual harassment at work | [15] |

| 1995 | N/A | N/A-46 | Definitions of sexual harassment | [16] |

| 1995 | N/A | N/A-64 | Sexual harassment at work | [17] |

| 1996 | N/A | N/A-54 | Sexual harassment in medical education | [18] |

| 1997 | N/A | N/A-46 | Sexual harassment at work—legal aspects of sexual harassment | [19] |

| 1998 | N/A | N/A-43 | Sexual harassment at work | [20] |

| 1998 | 1982–1996 | 111 | Gender difference in perceptions of sexual harassment | [21] |

| 1999 | N/A | N/A-128 | Sexual harassment at work | [22] |

| 1999 | N/A | N/A-124 | Sexual harassment at work | [23] |

| 1999 | 1987–1997 | 74 | Sexual harassment at work (Northern and Western countries) | [24] |

| 2000 | N/A | N/A-87 | Sexual harassment at work | [25] |

| 2000 | N/A | N/A-96 | Sexual harassment at work (Scandinavian context) | [26] |

| 2001 | 1969–1999 | 62 | Gender difference in perceptions of sexual harassment | [27] |

| 2003 | N/A | 71 | Sexual harassment at work | [28] |

| 2004 | N/A | N/A-84 | Interventions for sexual harassment at work | [29] |

| 2005 | N/A | N/A-135 | Sexual harassment on the Internet | [6] |

| 2005 | N/A | N/A-98 | Gender and communication incomputer mediated communication (CMC) environments | [30] |

| 2005 | N/A | N/A-68 | Role of gender in workplace stress | [31] |

| 2006 | N/A | N/A-30 | Sexual harassment at work and cross-cultural study of reaction to academic sexual harassment | [32] |

| 2006 | N/A | 182 | Women veterans’ health | [33] |

| 2007 | N/A | 41 | Sexual harassment at work | [34] |

| 2008 | N/A | N/A-73 | Aggression and sexual harassment in service encounters (sexual harassment at work) | [35] |

| 2008 | N/A | 49 | Sexual harassment at work | [36] |

| 2009 | 1995–2009 | N/A-151 | Sexual harassment at work | [37] |

| 2010 | N/A | N/A-73 | Interventions for sexual harassment at work | [38] |

| 2011 | N/A | N/A-147 | Sexual harassment at work | [1] |

| 2011 | N/A | 32 | Bullying in special education (Youth) | [39] |

| 2012 | N/A | N/A-121 | Sexual harassment at work | [40] |

| 2012 | N/A | N/A-157 | Sexual harassment at work | [41] |

| 2013 | N/A | N/A-35 | Peer sexual harassment (Youth) | [42] |

| 2014 | N/A | N/A-159 | Workplace injustices and occupational health disparities | [43] |

| 2014 | N/A | 136 | Bullying, violence and sexual harassment of nurses | [44] |

| 2015 | N/A | 60 | Interventions for sexual harassment at work | [45] |

| 2016 | N/A | N/A-73 | Sexual harassment and assault in the US military | [46] |

| 2017 | N/A | N/A-45 | Sexual harassment in academia | [47] |

| 2018 | 1995–2018 | 11 | Gender-based nature of technology-facilitated sexual violence (TFSV) | [48] |

| 2018 | N/A | 60 | Sexual harassment training | [45] |

| 2018 | N/A | N/A-122 | Sexual harassment at work | [49] |

| 2019 | 2000–2019 | 24 | Sexual harassment in higher education | [50] |

| 2019 | N/A | N/A-43 | Sexual harassment in academia | [51] |

| 2019 | N/A | N/A-105 | Sexual harassment at work | [52] |

| 2019 | 2005–2018 | 15 | Sexual harassment of nurses at work | [53] |

| 2019 | 2003–2019 | N/A-95 | Sexual cyberbullying | [54] |

| 2019 | N/A | N/A-67 | Sexual harassment | [55] |

| 2019 | N/A | N/A-134 | Sexual harassment at work | [56] |

| 2019 | 1990–2017 | 60 | Sexual harassment of refugees | [57] |

| 2020 | 1966–2017 | 30 | Sexual harassment in higher education | [58] |

| 2020 | N/A | 20 | Sexual harassment against female nurses at work | [59] |

| 2020 | 1980–2020 | 71 | Sexual harassment in transit environments | [60] |

| 2020 | N/A | N/A-109 | Sexual harassment of girls | [61] |

| Category/Topic | ID | Definition | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health Outcomes | Military Trauma | T19 | Research on the effects of sexual trauma in the military. Female veterans report more severe mental health outcomes due to sexual trauma. |

| Healthcare Services | T33 | Research on health issues of sexual harassment, including health outcomes and barriers to accessing health care for different communities such as LGBT veterans, Latina workers, military women, blind people, and homelessness people. | |

| Effects of Trauma Exposure | T36 | Research on the mental and physical effects of experiencing traumatic events. | |

| Sexual Harassment in Education | Higher Education | T2 | Research on sexual harassment in higher education with several articles focused on medicine. Studies addressed the prevalence of sexual harassment, perceptions of sexual harassment by members of academic institutions, and institutional policies and resources. |

| Youth Bullying and Victimization | T40 | Research on sexual harassment (e.g., bullying) in middle and high schools. | |

| Workspace | Professional Relationships | T6 | Research on cross-sex friendships and professional relationships. Multiple studies focused on cross-sex mentorship relations at work and in academic settings with many studies finding that these types of relationships could be challenging and lead to negative outcomes. |

| Workplace Harassment and Romance | T13 | Research on sexual harassment by coworkers and costumers. Additionally, workplace romance experiences and policies. | |

| Gender Equality in Workspace | T16 | Research on equality in the workplace, many articles studied the barriers and challenges (e.g., gender-based discrimination) that women experience in various workspaces. | |

| Poor Health Outcomes of Employees | T20 | Association between sexual harassment remarks or physical advances (e.g., bullying) and poor health outcomes of employees. | |

| Medical Field Discrimination | T21 | Research on training, perceptions, and experiences regarding professionalism among students and members in the medical field. Many studies found that women reported gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment. | |

| Workspace Policies | T26 | Research on developing sexual harassment policies in the workplace such as creating user-friendly sexual harassment policies. | |

| Hospital Workplace Violence | T31 | Articles studied the types of violence experienced by hospital staff members. Studies found that verbal abuse and threats by patients and patients’ family members were common. Additionally, medical staff experienced sexual harassment by other workers as well as patients. | |

| Historically Oppressed Populations | Sex Workers and HIV | T7 | Research on risk factors (e.g., drug use, sexual harassment/rape) that increase the risk of HIV infection among sex-workers. |

| Racial/Ethnic Discrimination | T22 | Research on racial/ethnic and gender discrimination, including sexual harassment and other forms of discrimination. Several articles focused on how the intersection between gender and race/ethnicity increases experiences of oppression and victimization. | |

| Global Society | T34 | Research on factors that increase vulnerability of low-income people; many articles focused on women. Studies assessed natural, structural, and environmental factors that increased vulnerability (e.g., natural disasters and social settings). Several articles focused on developing countries. | |

| Attitudes, Beliefs, and Perceptions | Sexual Harassing Behaviors | T1 | Research on individuals’ perceptions and attitudes related to sexual harassment behaviors. Several studies surveyed undergraduate students. |

| Perceptions of Sexual Harassment | T12 | Research using vignettes and hypothetical scenarios to study perceptions of sexual harassment and attributions of responsibility. Studies assessed how characteristics of the rater (e.g., gender attitudes), the target of harassment (e.g., attractiveness), and the perpetrator influenced individuals’ perceptions of the scenario. | |

| Sexist Beliefs and Masculinity | T28 | The influence of sexist beliefs and threat to masculinity on aggressive behavior, including tolerance for sexual harassment, self-reported perpetration of sexual harassment, and aggressive behaviors in experimental contexts. | |

| Sexual Harassment in the Legal Field | Workplace Legal Cases | T14 | Research on workspace sexual harassment within legal cases. Research included studies of factors that influence jurors (e.g., instructing jurors to adopt the rational woman standard) and legal decisions. |

| Discrimination Laws | T17 | Papers review laws and policies in different countries and regions (e.g., United States, United Kingdom, Australia, European Union) regarding sexual discrimination issues. | |

| Hegemonic Masculinity | T4 | Research on men’s dominant position and sexual harassment in different places such as work, academia, and public spaces. | |

| Domestic Violence | T18 | Research studies on topics related to domestic violence such as sexual violence among young couples. | |

| Digital Space | T23 | Research on risks of internet use (including phones, apps, cloud, blogs, social networks) with an emphasis on youth. | |

| Prevention and Treatment | T24 | Research on prevention and treatment of sexual violence and interpersonal violence (such as intimate partner violence and sexual harassment) within workplaces and other settings (e.g., community, schools) | |

| Feminism, Media, and Politics | T25 | Research on portrayals in media and politics of sexual harassment. Most articles focused on the Hill–Thomas hearing and the #MeToo movement. | |

| Coping Reactions | T37 | Research on reactions (e.g., coping strategies) around sexual harassment. | |

| Category/Topic | ID | Slope | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health Outcomes | Military Trauma | T19 | R > 0 | * |

| Healthcare Services | T33 | R > 0 | * | |

| Effects of Trauma Exposure | T36 | R > 0 | * | |

| Sexual Harassment in Education | Higher Education | T2 | R < 0 | * |

| Youth Bullying and Victimization | T40 | R > 0 | * | |

| Workspace | Professional Relationships | T6 | ns | ns |

| Workplace Harassment and Romance | T13 | ns | ns | |

| Gender Equality in Workspace | T16 | R < 0 | * | |

| Poor Health Outcomes of Employees | T20 | ns | ns | |

| Medical Field Discrimination | T21 | R > 0 | * | |

| Workspace Policies | T26 | R < 0 | * | |

| Hospital Workplace Violence | T31 | R > 0 | * | |

| Historically Oppressed Populations | Sex Worker and HIV | T7 | R > 0 | * |

| Racial/Ethnic Discrimination | T22 | ns | ns | |

| Global Society | T34 | ns | ns | |

| Attitudes, Beliefs, and Perceptions | Sexual Harassing Behaviors | T1 | R < 0 | * |

| Perceptions of Sexual Harassment | T12 | R < 0 | * | |

| Sexist Beliefs and Masculinity | T28 | ns | ns | |

| Sexual Harassment in the Legal Field | Workplace Legal Cases | T14 | R < 0 | * |

| Discrimination Laws | T17 | ns | ns | |

| Hegemonic Masculinity | T4 | ns | ns | |

| Domestic Violence | T18 | R > 0 | * | |

| Digital Space | T23 | R > 0 | * | |

| Prevention and Treatment | T24 | ns | ns | |

| Feminism, Media, and Politics | T25 | R > 0 | * | |

| Coping Reactions | T37 | ns | ns | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Karami, A.; Spinel, M.Y.; White, C.N.; Ford, K.; Swan, S. A Systematic Literature Review of Sexual Harassment Studies with Text Mining. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6589. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126589

Karami A, Spinel MY, White CN, Ford K, Swan S. A Systematic Literature Review of Sexual Harassment Studies with Text Mining. Sustainability. 2021; 13(12):6589. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126589

Chicago/Turabian StyleKarami, Amir, Melek Yildiz Spinel, C. Nicole White, Kayla Ford, and Suzanne Swan. 2021. "A Systematic Literature Review of Sexual Harassment Studies with Text Mining" Sustainability 13, no. 12: 6589. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126589

APA StyleKarami, A., Spinel, M. Y., White, C. N., Ford, K., & Swan, S. (2021). A Systematic Literature Review of Sexual Harassment Studies with Text Mining. Sustainability, 13(12), 6589. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126589