Motivational Factors, Job Satisfaction, and Economic Performance in Romanian Small Farms

Abstract

1. Introduction

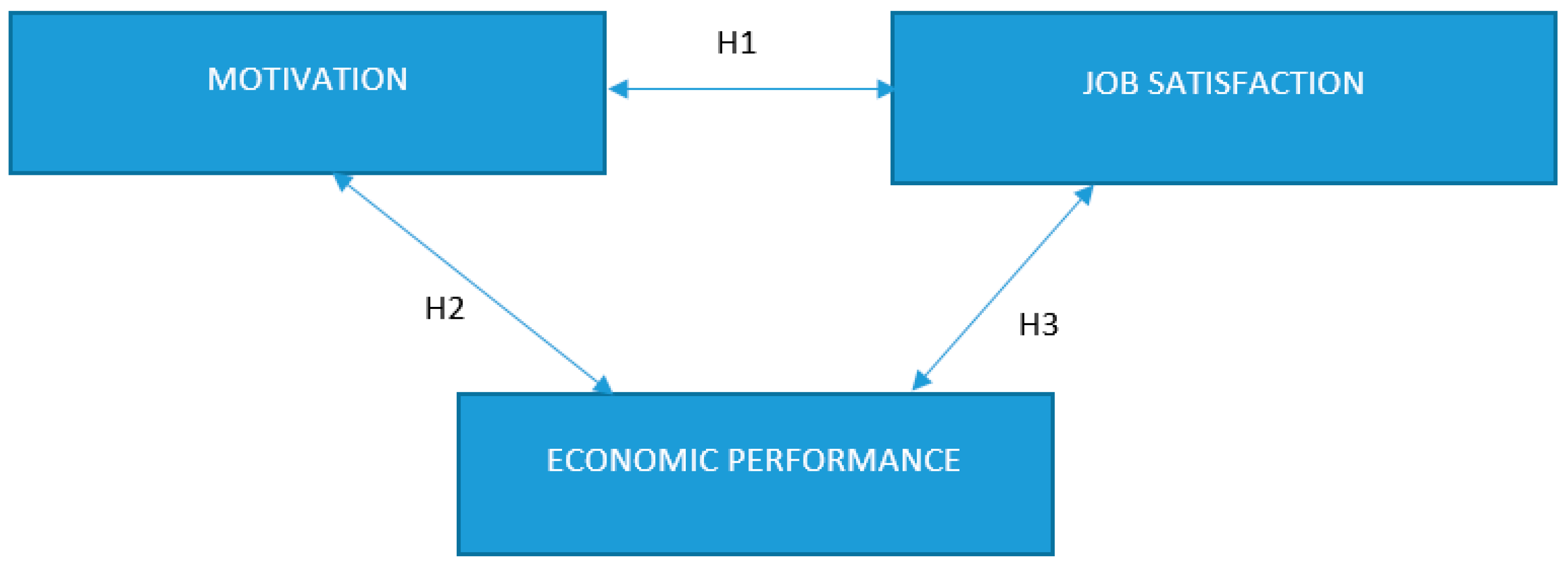

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Motivation

2.2. Job Satisfaction

2.3. Farm Economic Performance

3. Materials and Methods

- -

- Providing better knowledge on the subject, as there are only a few studies that consider the relation between motivation, job satisfaction, and farm performance with regard to small farms; most studies consider these relations for other types of businesses.

- -

- Using a unique set of variables, we succeeded in creating a structural model that describes the relations that appear, in the case of farmers on small farms, between farmers’ motivation, their satisfaction and, in the end, the performance of their farms.

Sample and Data Collection

4. Results

5. Discussions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eurostat Website. Agriculture, Forestry and Fishery Statistics, 2020 Edition. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3217494/12069644/KS-FK-20-001-EN-N.pdf/a7439b01-671b-80ce-85e4-4d803c44340a?t=1608139005821 (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Romania’s Sustainable Development Strategy 2030, RSDS, Government of Romania, Bucharest. 2018. Available online: http://dezvoltaredurabila.gov.ro/web/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Romanias-Sustainable-Development-Strategy-2030 (accessed on 22 April 2021).

- Ungureanu, A.; Andrei, J.V. Economic Structure Evolution in Achieving Performance from Agrarian Economy to Competitiveness in Romanian Economy. Econ. Agric. 2014, 4, 945–957. [Google Scholar]

- Rizov, M.; Gavrilescu, D.; Gow, H.; Mathijs, E.; Swinnen, J.F. Transition and enterprise restructuring: The development of individual farming in Romania. World Dev. 2001, 29, 1257–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciutacu, C.; Chivu, L.; Andrei, J.V. Similarities and dissimilarities between the EU agricultural and rural development model and Romanian agriculture. Challenges and perspectives. Land Use Policy 2015, 44, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrei, J.V.; Popescu, G.H.; Nica, E.; Chivu, L. The impact of agricultural performance on foreign trade concentration and competitiveness: Empirical evidence from Romanian agriculture. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2020, 21, 317–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovici, D.A.; Gorton, M. An evaluation of the importance of subsistence food production for assessments of poverty and policy targeting: Evidence from Romania. Food Policy 2005, 30, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, C.; Mishev, P.; Ivanova, N.; Luca, L. Semi-subsistence farming in Romania and Bulgaria: A survival strategy? Eurochoices 2014, 13, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathijs, E.; Noev, N. Subsistence farming in central and Eastern Europe: Empirical evidence from Albania, Bulgaria, Hungary, and Romania. East. Eur. Econ. 2014, 42, 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PwC Romania. Comunicat de presă. Studiu PwC Sectorul Agricol din România. Available online: https://www.pwc.ro/en/press_room/assets/2017/RO/Comunicat%20de%20presa%20PwC_Studiu%20PwC%20sectorul%20agricol%20din%20Romania_final.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Eurostat Website. Gross Value Added at Current Prices, 2009 and 2019. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/images/8/8f/Gross_value_added_at_current_basic_prices%2C_2009_and_2019_%28%25_share_of_total_gross_value_added%29.png (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- Romanian National Institute of Statistics. Comunicat de Presă. Ocuparea și Șomajul 2019. 2019. Available online: https://insse.ro/cms/sites/default/files/com_presa/com_pdf/somaj_2019r.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2021).

- Eurostat Website. Agricultural Labour Productivity down by 4% in 2020. 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/ddn-20201216-1?redirect=%2Feurostat%2Fweb%2Fagriculture%2Fpublications (accessed on 19 December 2020).

- McCullough, E.B.; Pingali, P.L.; Stamoulis, K.G. Small farms and the transformation of food systems: An overview. In Looking East, Looking West: Organic and Quality Food Marketing in Asia and Europe; Haas, R., Canavari, M., Slee, B., Tong, C., Anurugsa, B., Eds.; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 47–83. [Google Scholar]

- Berti, G.; Mulligan, C. Competitiveness of Small Farms and Innovative Food Supply Chains: The Role of Food Hubs in Creating Sustainable Regional and Local Food Systems. Sustainability 2016, 8, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, M.; Guarín, A.; Pinto-Correia, T.; Almaas, H.; Mur, L.A.; Burns, V.; Czekaj, M.; Ellis, R.; Galli, F.; Grivins, M.; et al. Assessing the role of small farms in regional food systems in Europe: Evidence from a comparative study. Glob. Food Sec. 2020, 26, 100417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmioli, L.; Grando, S.; Di Iacovo, F.; Fastelli, L. Small farms’ strategies between self-provision and socio-economic integration: Effects on food system capacity to provide food and nutrition security. Local Environ. 2020, 25, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, J.; Farrell, M.; Conway, S. The Role of Small-Scale Farms and Food Security. In Sustainability Challenges in the Agrofood Sector, ch. 2; Bhat, R., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Arnalte-Mur, L.; Ortiz-Miranda, D.; Cerrada-Serra, P.; Martinez-Gómez, V.; Moreno-Pérez, O.; Barbu, R.; Bjorkhaug, H.; Czekaj, M.; Duckett, D.; Galli, F.; et al. The drivers of change for the contribution of small farms to regional food security in Europe. Glob. Food Secur. 2020, 26, 100395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardakani, Z.; Bartolini, F.; Brunori, G. New Evaluation of Small Farms: Implication for an Analysis of Food Security. Agriculture 2020, 10, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiggins, S.; Kirsten, J.; Llambí, L. The Future of Small Farms. World Dev. 2010, 38, 1341–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulton, C.; Dorward, A.; Kydd, J. The Future of Small Farms: New Directions for Services, Institutions, and Intermediation. World Dev. 2010, 38, 1413–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazell, P.; Poulton, C.; Wiggins, S.; Dorward, A. The Future of Small Farms: Trajectories and Policy Priorities. World Dev. 2010, 38, 1349–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, K.; Liu, Y.; Yamauchi, F. The future of small farms in Asia. Dev. Policy Rev. 2016, 34, 441–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazell, P.B.; Poulton, C.; Wiggins, S.; Dorward, A. The Future of Small Farms for Poverty Reduction and Growth; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2007; pp. 3–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazell, P.; Poulton, C.; Wiggins, S.; Dorward, A. The Future of Small Farms: Synthesis Paper; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Boyce, J.K. A Future for Small Farms? Biodiversity and Sustainable Agriculture, Chapters. In Human Development in the Era of Globalization, ch. 4; Boyce, J.K., Cullenberg, S., Pattanaik, P.K., Pollin, R., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing Inc.: Northampton, MA, USA, 2006; pp. 83–105. [Google Scholar]

- Birol, E.; Smale, M.; Gyovai, Á. Using a Choice Experiment to Estimate Farmers’ Valuation of Agrobiodiversity on Hungarian Small Farms. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2006, 34, 439–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidova, S.; Bailey, A. Roles of Small and Semi-subsistence farms in the EU. EuroChoices 2014, 13, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkov, A.; Balezentis, T.; Morkunas, M.; Streimikiene, D. Who Benefits from CAP? The Way the Direct Payments System Impacts Socioeconomic Sustainability of Small Farms. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhavein, J.; Goldberg, L.G.; White, L.J. Small Banks, Small Business, and Relationships: An Empirical Study of Lending to Small Farms. J. Financ. Serv. Res. 2004, 26, 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, M.R. Equilibrium credit rationing of small farm agriculture. J. Dev. Econ. 1988, 28, 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarín, A.; Rivera, M.; Pinto-Correia, T.; Guiomar, N.; Šūmane, S.; Moreno-Pérez, O.M. A new typology of small farms in Europe. Glob. Food Secur. 2020, 26, 100389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tisenkopfs, T.; Adamsone-Fiskovica, A.; Kilis, E.; Šūmane, S.; Grivins, M.; Pinto-Correia, T.; Bjørkhaug, H. Territorial fitting of small farms in Europe. Glob. Food Secur. 2020, 26, 100425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostov, P.; Lingard, J. Subsistence agriculture in transition economies: Its roles and determinants. J. Agric. Econ. 2004, 55, 565–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidova, S.; Fredriksson, L.; Bailey, A. Subsistence and semi-subsistence farming in selected EU new member states. Agric. Econ. 2009, 40, 733–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, G.; Ikerd, J. Small Farms and Sustainable Development: Is Small More Sustainable? J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 1996, 28, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. What Is a Small Farm? EU Agricultural Economics Brief, 2; European Commission, Agriculture and Rural Development: Brussels, Belgium, 2011; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/food-farming-fisheries/farming/documents/agri-economics-brief-02_en.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2020).

- Guiomar, N.; Godinho, S.; Pinto-Correia, T.; Almeida, M.; Bartolini, F.; Bezák, P.; Wästfelt, A. Typology and distribution of small farms in Europe: Towards a better picture. Land Use Policy 2018, 75, 784–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowder, S.K.; Skoet, J.; Raney, T. The number, size, and distribution of farms, smallholder farms, and family farms worldwide. World Dev. 2016, 87, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruchelski, M.; Niemczyk, J. Małe gospodarstwa rolne w Polsce a paradygmat rozwoju zrównowaz˙onego (Small farms in Poland and the paradigm of sustainable development). Adv. Food Process. Tech. 2016, 2, 134–140. Available online: http://yadda.icm.edu.pl/yadda/element/bwmeta1.element.baztech-13034245-6bd0-4637-a6f8-99082a44fe93?q=bwmeta1.element.baztech-27e8fc23-5865-4c54-8ede-0bf031c376b3;22&qt=CHILDREN-STATELESS (accessed on 2 November 2020).

- Żmija, A.; Alexandri, C.; Czyżewski, A.; Gorlach, K.; Kaleta, A.; Kłodziński, M.; Kozari, J.; Sorys, S.; Urban, S.; Vanni, F.; et al. (Eds.) Problemy Społeczne i Ekonomiczne Drobnych Gospodarstw Rolnych w Europie [Social and Economic Problems of Small Farms in Europe]; Agricultural Advisory Center: Crocow, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- FADN Database. 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/rica/database/database_en.cfm (accessed on 2 November 2020).

- Law No. 37/2015, Published in Monitorul Oficial al României, Part. 1, No. 172 from 12th March 2015. Available online: https://www.monitoruloficial.ro/actimp/hu/0020_2015.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2020).

- Stępień, S.; Maican, S. Small Farms in the Paradigm of Sustainable Development. Case Studies of Selected Central and Eastern European Countries; Adam Marszałek Publishing House: Torun, Poland, 2020; pp. 55–74. [Google Scholar]

- Poczta-Wajda, A.; Sapa, A.; Stępień, S.; Borychowski, M. Food Insecurity among Small-Scale Farmers in Poland. Agriculture 2020, 10, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, N.; Popa, R. Family Farming in Romania, Fundația ADEPT Transilvania. 2013. Available online: www.fundatia-adept.org (accessed on 17 March 2019).

- Otiman, P.I. Romania’s Present Agrarian Structure: A Great (and Unsolved) Social and Economic Problem of Our Country. Agric. Econ. Rural Dev. 2012, 3–24. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/a/lum/rev19g/v5-6y2012ip339-360.html (accessed on 25 April 2021).

- Stanton, B.F. Perspective on Farm Size. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 1978, 60, 727–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Agriculture, Forestry and Fishery Statistics, Statistical Books. 2018. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3217494/9455154/KS-FK-18-001-EN-N.pdf/a9ddd7db-c40c-48c9-8ed5-a8a90f4faa3f (accessed on 30 August 2019).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2019. Available online: http://www.fao.org/family-farming/countries/rou/en/ (accessed on 3 October 2019).

- Burja, C.; Burja, V. Sustainable development of rural areas: A challenge for Romania. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2014, 13, 1861–1871. Available online: http://www.eemj.icpm.tuiasi.ro/pdfs/vol13/no8/Full/2_161_Burja_14.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2019). [CrossRef]

- Burja, C.; Burja, V. Adapting the Romanian rural economy to the European agricultural policy from the perspective of sustainable development. MPRA Munich Pers. RePEc Arch. 2008. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/7989/1/MPRA_paper_7989.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2019).

- Burja, V.; Moraru, C.; Rusu, O. Sustainable development of the Romanian rural areas. Ann. Univ. Apulensis Ser. Oeconomica 2008, 2, 1–27. Available online: http://www.oeconomica.uab.ro/upload/lucrari/1020082/27.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2019).

- Neculai, C. The Quality of Life at Common’s Level in Romanian Rural Areas. In Proceedings of the 4th WSEAS World Multiconference on Applied Economics, Business and Development (AEBD ‘12), Porto, Portugal, 1–3 July 2012; pp. 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Săvoiu, G.; Manea, C.; Manea, C. The Romanian Rural Economy—A Resource of Growth and Regional Cooperation, or a Source of Conflicts and Insecurity? Rom. Econ. J. 2007, 187–200. [Google Scholar]

- Borychowski, M.; Stępień, S.; Polcyn, J.; Tošović-Stevanović, A.; Ćalović, D.; Lalić, G.; Žuža, M. Socio-Economic Determinants of Small Family Farms’ Resilience in Selected Central and Eastern European Countries. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papakostantinou, G.; Anastasiou, S. Principles of Human Resource Management; Gutenberg: Athens, Greece, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jankelová, N.; Joniaková, Z.; Romanová, A.; Remeňová, K. Motivational factors and job satisfaction of employees in agriculture in the context of performance of agricultural companies in Slovakia. Agric. Econ. 2020, 66, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahito, Z.; Vaisanen, P. The diagonal model of job satisfaction and motivation: Extracted from the logical comparison of content and process theories. Int. J. High. Edu. 2017, 3, 209–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayona, J.A.; Caballer, A.; Peiró, J.M. The Relationship between Knowledge Characteristics’ Fit and Job Satisfaction and Job Performance: The Mediating Role of Work Engagement. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, S.; Komil ugli Fayzullaev, A.; Dedahanov, A.T. Management Characteristics as Determinants of Employee Creativity: The Mediating Role of Employee Job Satisfaction. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortini, M.; Converso, D.; Galanti, T.; Di Fiore, T.; Di Domenico, A.; Fantinelli, S. Gratitude at Work Works! A Mix-Method Study on Different Dimensions of Gratitude, Job Satisfaction, and Job Performance. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Extremera, N.; Mérida-López, S.; Quintana-Orts, C.; Rey, L. On the association between job dissatisfaction and employee’s mental health problems: Does emotional regulation ability buffer the link? Personal. Individ. Differ. 2020, 155, 109710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziri, B. Job Satisfaction: A Literature Review. Manag. Res. Pract. 2011, 3, 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S.P.; Peterson, R.A. The effect of effort on sales performance and job satisfaction. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullins, L.J. Management and Organisational Behaviour; Pearson Education: Essex, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Nel, P.S.; Haasbroek, G.D.; Schultz, H.B.; Sono, T.; Werner, A. Human Resources Management, 6th ed.; Oxford University Press: Cape Town, South Africa, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bush, T.; Middlewood, D. Leading and Managing People in Education; Sage: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Danish, R.Q.; Usman, A. Impact of reward and recognition on job satisfaction and motivation: An empirical study from Pakistan. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 5, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, K.R.; Williams, P.L. Personality Characteristics and Successful Use of Credit by Farm Families. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 1971, 53, 619–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavas, J.P.; Chambers, R.G.; Pope, R.D. Production Economics and Farm Management: A Century of Contributions. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2010, 92, 356–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, W.W. The Human Factor from the Viewpoint of Farm Management. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 1932, 14, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case, H.C.M.; Williams, D.B. Research Attitudes in Farm Management. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 1951, 33, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moxley, C.C. Creating a Work Environment in which Farm Employment Is Competitive: Discussion. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 1970, 52, 792–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasson, R. Goals and Values of Farmers. J. Agric. Econ. 1973, 24, 521–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willock, J.; Deary, I.J.; Edwards-Jones, G.; Gibson, G.J.; McGregor, M.J.; Sutherland, A.; Dent, J.B.; Morgan, O.; Grieve, R. The Role of Attitudes and Objectives in Farmer Decision Making: Business and Environmentally Oriented Behavior in Scotland. J. Agric. Econ. 1999, 50, 286–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guither, H.D. Factors Influencing Farm Operators’ Decisions to Leave Farming. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 1963, 45, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wu, Q. A Study of Farmers’ Rationality Based on Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Asian Agric. Res. 2015, 7, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnhofer, I.; Schneeberger, W.; Freyer, B. Converting or Not Converting to Organic Farming in Austria: Farmer Types and Their Rationale. Agric. Hum. Values 2005, 22, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karali, E.; Brunner, B.; Doherty, R.; Hersperger, A.; Rounsevell, M. Identifying the factors that influence farmer participation in environmental management practices in Switzerland. Hum. Ecol. 2014, 42, 951–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, N.; Jenson, G.; Bailey, D. Farm Work and Family: Major Sources of Satisfaction for Farm Families. Utah Sci. 1989, 50, 134–142. [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann, V.; Uttitz, P. If Only I Didn’t Enjoy Being a Farmer! Attitudes and Opinions of Monoactive and Pluriactive Farmers. Sociol. Rural. 1990, 30, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oloruntoba, A.; Ajayi, M.T. Motivational Factors and Employees’ Job Satisfaction in Large-Scale Private Farms in Ogun State, Nigeria. J. Int. Agric. Ext. Edu. 2003, 10, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, C.D.; Reed, D.B.; Rayens, M.K.; Hunsucker, S. Predictors of Job Satisfaction in Female Farmers Aged 50 and Over: Implications for Occupational Health Nurses. Workplace Health Saf. 2020, 68, 526–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliski, B. Encyclopedia of Business and Finance, 2nd ed.; MacMillan Reference Books: Detroit, MI, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Asiedu-Darko, E.; Amanor, M. Factors affecting job satisfaction of agricultural sector workers in Ghana. Am. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2016, 4, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellickson, M.; Logsdon, K. Determinants of job satisfaction of municipal and government employees. State Local Gov. Rev. 2001, 33, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghradi, A. Assessing the effect of job satisfaction on managers. Int. J. Value-Based Manag. 1999, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.; Ismail, W.K.W.; Rasid, S.Z.A.; Selemani, R.D.A. The impact of human resource management practices on performance: Evidence from a Public University. TQM J. 2014, 26, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, N.; Johansson, E. New evidence on cross-country differences in job satisfaction using anchoring vignettes. Labour Econ. 2008, 15, 96–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirlam, J.; Zheng, H. Job satisfaction developmental trajectories and health: A life course perspective. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 178, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgard, S.; Lin, K. Bad Jobs, bad health? How work and working conditions contribute to health disparities. Am. Behav. Sci. 2013, 57, 1105–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dessler, G. Human Resource Management; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gârdan, D.A.; Andronie, M.; Gârdan, I.P.; Andronie, I.E.; Iatagan, M.; Hurloiu, I. Bioeconomy development and using of intellectual capital for the creation of competitive advantages by SMEs in the field of biotechnology. Amfiteatru Economic 2018, 20, 647–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, J. The Top 10 Factors for on-the-Job Employee Happiness. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/jacobmorgan/2014/12/15/the-top-10-factors-for-on-the-job-employee-happiness/ (accessed on 6 December 2021).

- Herrera, B.; Gerster-Bentaya, M.; Knierim, A. Farm-level factors influencing farmers satisfaction with their work. In Proceedings of the International Association of Agricultural Economists (IAAE) 2018 Conference, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 28 July–2 August 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hundley, G. Why and when are the Self-Employed More Satisfied with Their Work? Ind. Relat. 2001, 40, 293–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovits, Y.; Davis, A.J.; Van Dick, R. Organizational commitment profiles and job satisfaction among Greek private and public sector employees. Int. J. Cross Cult. Manag. 2007, 7, 77–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jantsch, A.; Weirowski, T.; Hirschauer, N. (Dis-)Satisfaction in Agriculture? An Explorative Analysis of Job and Life Satisfaction in East Germany. Ger. J. Agric. Econ. (Online) 2019, 68, 263–274. [Google Scholar]

- Howley, P. The Happy Farmer: The Effect of Nonpecuniary Benefits on Behavior. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2015, 97, 1072–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benz, M.; Frey, B.S. The value of doing what you like: Evidence from the self-employed in 23 countries. J. Econ. Behav. Org. 2008, 68, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harling, K.F.; Quail, P. Exploring a general management approach to farm management. Agribusiness 1990, 6, 425–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, N.C. Reducing Stress of Farm Men and Women. Fam. Relat. 1987, 36, 358–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchflower, D.G.; Oswald, A. What Makes an Entrepreneur? J. Labor Econ. 1998, 16, 29–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benz, M.; Frey, B.S. Being Independent Is a Great Thing: Subjective Evaluations of Self-employment and Hierarchy. Economica 2008, 75, 362–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, C.N.; Franz, R.S. Work-related attitudes of entrepreneurs, public, and private employees. Psychol. Rep. 1992, 70, 387–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasiou, S.; Karipoglou, K.; Nathanailides, C. Participation in Decision Making, Productivity and Job Satisfaction among Managers of Fish Farms in Greece. Int. Bus. Res. 2014, 7, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juntunen, C.L.; Gallina, M.F.; Bailey, T.-K.M.; Hunsaker, M.L.; Burandt, R.; Huff-Pomstra, T.L.; Munch, J.A.; Burshek, K.; Ayala, E.; Huttar, M.P. Farmers and Ranchers in North Dakota Value Their Land in Not Only Economic Terms. Ecopsychology 2019, 11, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Căpuşneanu, S.; Ivan, R.; Topor, D.I.; Oprea, D.-M.; Muntean, A. Environmental Changes and their Influences on Performance of a Company by Using Eco-dashboard. J. Environ. Prot. Ecol. 2015, 16, 1091–1100. [Google Scholar]

- Czyżewski, B.; Matuszczak, A.; Grzelak, A.; Guth, M.; Majchrzak, A. Environmental sustainable value in agriculture revisited: How does Common Agricultural Policy contribute to eco efficiency? Sustain. Sci. 2021, 16, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauer, J.; Moreddu, C. Drivers of Farm Performance: Empirical Country Case Studies. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/agriculture-and-food/drivers-of-farm-performance_248380e9-en (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Kimura, S.; Sauer, J. Dynamics of Dairy Farm Productivity Growth: Cross-Country Comparison; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauer, J.; Morrison, C.J. The empirical identification of heterogeneous technologies and technical change. Appl. Econ. 2013, 45, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isac, C. Management of succession in family businesses. Qual. Access Success J. 2019, 20, 423–428. [Google Scholar]

- Andronie, M.; Gârdan, D.A.; Dumitru, I.; Gârdan, I.P.; Andronie, I.E.; Uță, C. Integrating the Principles of Green Marketing by Using Big Data. Good Practices. Amfiteatru Econ. J. 2019, 21, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tošović-Stevanović, A.; Ristanović, V.; Ćalović, D.; Lalić, G.; Žuža, M.; Cvijanović, G. Small Farm Business Analysis Using the AHP Model for Efficient Assessment of Distribution Channels. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzberg, F.; Bernard, M.; Snyderman, B. The Motivation to Work; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Grzelak, A.; Guth, M.; Matuszczak, A.; Czyżewski, B.; Brelik, A. Approaching the environmental sustainable value in agriculture: How factor endowments foster the eco-efficiency. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 241, 118304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czyżewski, B.; Poczta-Wajda, A. Effects of Policy and Market on Relative Income Deprivation of Agricultural Labour. In Proceedings of the 160th EAAE Seminar ‘Rural Jobs and the CAP’, Warsaw, Poland, 1–2 December 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, S. Is work satisfaction dependent on wage levels? Insights from a cross-country study. Int. J. Happiness Dev. 2018, 4, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Näther, M.; Stratmann, J.; Bendfeldt, C.; Theuvsen, L. Which factors influence the job satisfaction of agricultural employees? In Proceedings of the XXVI European Society for Rural Sociology Congress, Aberdee, Scotland, 18–21 August 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mcdonald, N.J. Exploring Cotton Farm Workers’ Job Satisfaction by Adapting Social Cognitive Career Theory to the Farm Work Context; University of Southern Queensland: Toowoomba, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R.W.; Brown, S.D. Integrating person and situation perspectives on work satisfaction: A social-cognitive view. J. Vocat. Behav. 2006, 69, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Braun, J.; Mirzabaev, A. Small Farms: Changing Structures and Roles in Economic Development. SSRN Electron. J. 2015, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahan, D. Economics for Farm Management Extension; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2013; Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/i3228e/i3228e.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- Xiao, D.; Niu, H.; Fan, L.; Zhao, S.; Yan, H. Farmers’ Satisfaction and its Influencing Factors in the Policy of Economic Compensation for Cultivated Land Protection: A Case Study in Chengdu, China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellon-Bedi, S.; Descheemaeker, K.; Hundie-Kotu, B.; Frimpong, S.; Groot, J.C. Motivational factors influencing farming practices in northern Ghana. NJAS Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2020, 92, 100326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faragher, E.B.; Cass, M.; Cooper, C.L. The relationship between job satisfaction and health: A meta-analysis. Occup. Environ. Med. 2005, 62, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, M.T.; Heinen, B.A.; Langkamer, K.L. Work and family satisfaction and conflict: A meta-analysis of cross-domain relations. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 57–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Research Publications Repository. Synopsis: Towards a Framework for Unlocking Transformative Agricultural Innovation. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/102.100.100/88656?index=1 (accessed on 5 May 2021).

| Variable | Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of farm | Crops | 468 | 52.0 |

| Animals | 121 | 13.4 | |

| Mixed | 311 | 34.6 | |

| Farm manager gender | Male | 658 | 73.1 |

| Female | 242 | 26.9 | |

| Agricultural education | Yes | 509 | 56.6 |

| No | 391 | 43.4 | |

| Farm area | Under 5 ha | 390 | 43.3 |

| 5–10 ha | 242 | 26.9 | |

| Over 10 ha | 268 | 29.8 | |

| Region | Moldova | 260 | 28.9 |

| Transylvania | 270 | 30.0 | |

| Dobrogea | 280 | 31.1 | |

| Oltenia | 90 | 10.0 |

| Test | Motivation | Satisfaction | Farm Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cronbach’s alpha | 0.78 | 0.98 | 0.78 |

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy | 0.78 | 0.77 | 0.67 |

| Approximate chi-square | 974.57 | 4530.88 | 752.42 |

| Bartlett’s test of sphericity | 6 | 3 | 3 |

| Sig. | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

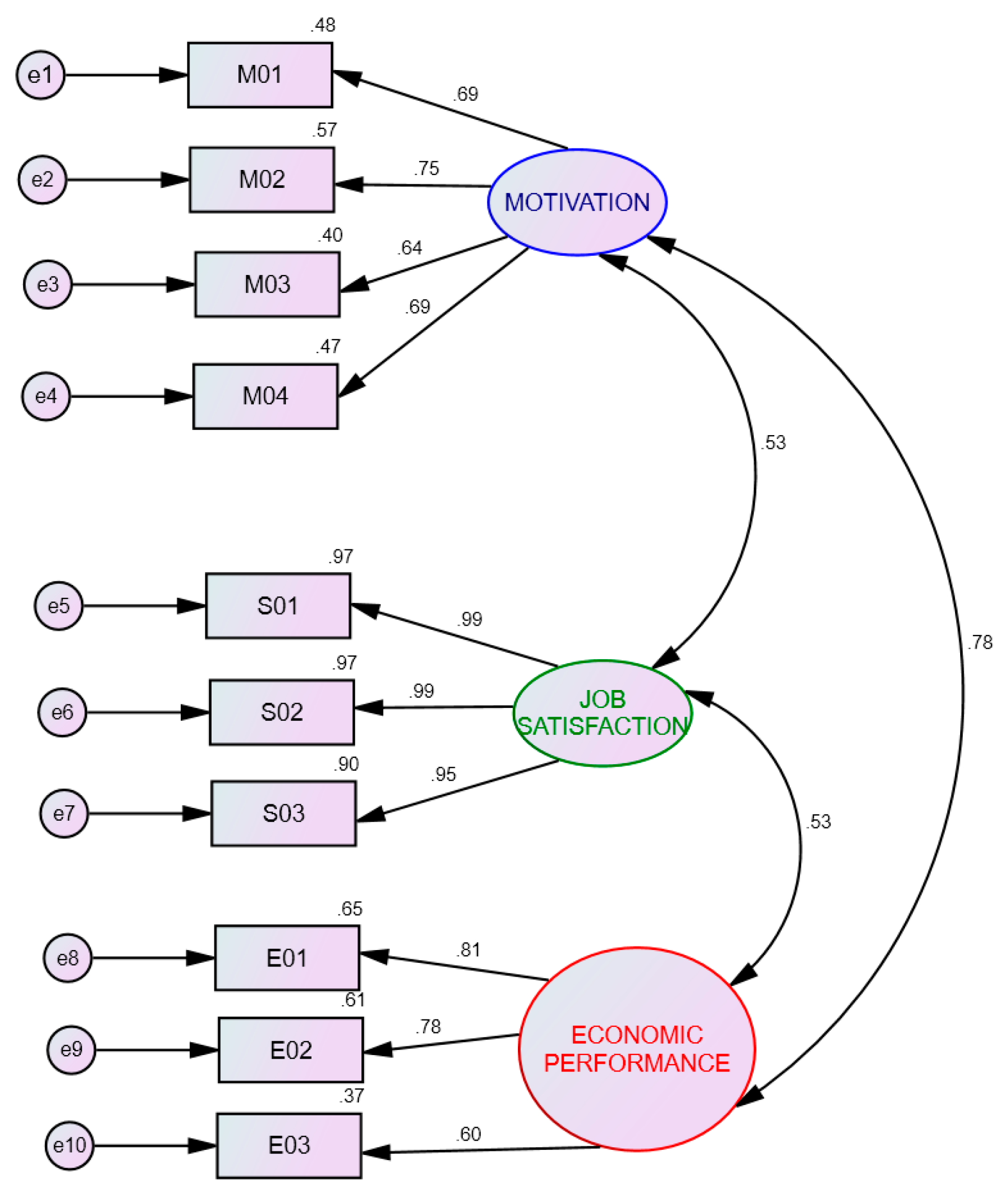

| Model | P | GFI | RMSEA | PCLOSE | CFI | NFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obtained research values | 0 | 0.96 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.98 | 0.97 |

| Theoretical statistical values | <0.05 | >0.90 | <0.10 | <0.05 | >0.95 | >0.95 |

| Model | TLI | RFI | PGFI | PNFI | PCFI | |

| Obtained research values | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.56 | 0.69 | 0.69 | |

| Theoretical statistical values | >0.95 | >0.90 | >0.50 | >0.50 | >0.50 |

| β | S.E. | C.R. | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOTIVATION | <--> | ECONOMIC_PERFORMANCE | 0.08 | 0.006 | 13.234 | *** |

| JOB_SATISFACTION | <--> | ECONOMIC_PERFORMANCE | 0.05 | 0.004 | 12.213 | *** |

| MOTIVATION | <--> | JOB_SATISFACTION | 0.04 | 0.004 | 11.644 | *** |

| ρ | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| MOTIVATION | <--> | ECONOMIC_PERFORMANCE | 0.78 |

| JOB_SATISFACTION | <--> | ECONOMIC_PERFORMANCE | 0.53 |

| MOTIVATION | <--> | JOB_SATISFACTION | 0.53 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maican, S.Ș.; Muntean, A.C.; Paștiu, C.A.; Stępień, S.; Polcyn, J.; Dobra, I.B.; Dârja, M.; Moisă, C.O. Motivational Factors, Job Satisfaction, and Economic Performance in Romanian Small Farms. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5832. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13115832

Maican SȘ, Muntean AC, Paștiu CA, Stępień S, Polcyn J, Dobra IB, Dârja M, Moisă CO. Motivational Factors, Job Satisfaction, and Economic Performance in Romanian Small Farms. Sustainability. 2021; 13(11):5832. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13115832

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaican, Silvia Ștefania, Andreea Cipriana Muntean, Carmen Adina Paștiu, Sebastian Stępień, Jan Polcyn, Iulian Bogdan Dobra, Mălina Dârja, and Claudia Olimpia Moisă. 2021. "Motivational Factors, Job Satisfaction, and Economic Performance in Romanian Small Farms" Sustainability 13, no. 11: 5832. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13115832

APA StyleMaican, S. Ș., Muntean, A. C., Paștiu, C. A., Stępień, S., Polcyn, J., Dobra, I. B., Dârja, M., & Moisă, C. O. (2021). Motivational Factors, Job Satisfaction, and Economic Performance in Romanian Small Farms. Sustainability, 13(11), 5832. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13115832