The Relation between Collaborative Consumption and Subjective Well-Being: An Analysis of P2P Accommodation

Abstract

1. Introduction

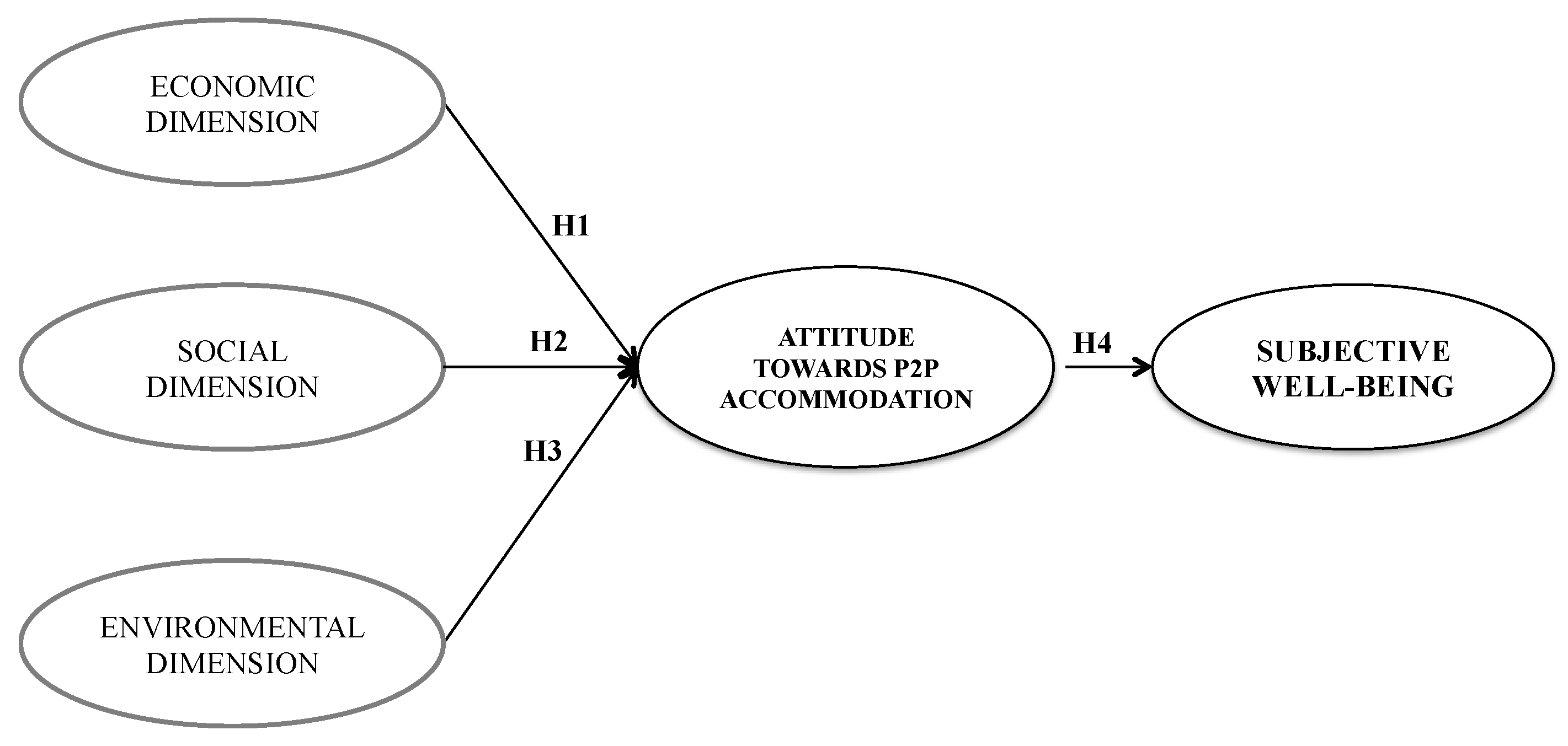

2. Theory and Hypothesis

2.1. Collaborative Consumption

2.2. Sharing Motives

2.2.1. Economic Dimension

2.2.2. Social Dimension

2.2.3. Environmental Dimension

2.3. Attitude towards P2P Accommodation

2.4. Well-Being and Well-Being in Tourism

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Qualitative Analysis: Data Collection

3.2. Quantitative Analysis: Data Collection

4. Results

4.1. Qualitative Results

4.2. Quantitative Results

5. Discussion and Conclusions

6. Limitations and Future Researches

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rudmin, F. The consumer science of sharing: A discussant’s observations. J. Assoc. Consum. Res. 2016, 1, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, S.; Baker, T.L.; Bolton, R.N.; Gruber, T.; Kandampully, J. A triadic framework for collaborative Consumption (CC): Motives, activities and resources & capabilities of actors. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 79, 219–227. [Google Scholar]

- Böcker, L.; Meelen, T. Sharing for people, planet or profit? Analysing motivations for intended sharing economy participation. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2017, 23, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, K.; Clarence, E.; Anderson, L.; Rinne, A. Making Sense of the UK Collaborative Economy; Nesta: London, UK, 2014; Volume 49. [Google Scholar]

- Gansky, L. The Mesh: Why the Future of Business is Sharing; Penguin: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.H.; Huang, T.Y. High-speed rail passengers’ mobile ticketing adoption. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2013, 30, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pietro, L.; Mugion, R.G.; Mattia, G.; Renzi, M.F.; Toni, M. The Integrated Model on Mobile Payment Acceptance (IMMPA): An empirical application to public transport. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2015, 56, 463–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M. Customer involvement in sustainable supply chain management: A research framework and implications in tourism. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2014, 55, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, S.J.; Mattsson, J. Understanding current and future issues in collaborative Consumption: A four-stage Delphi study. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2016, 104, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R.W. Possessions and the Extended Self. J. Consum. Res. 1988, 15, 139–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Esterick, P. Generating status symbols: You are what you own. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the Association for Consumer Research, Toronto, ON, Canada, 16–19 October 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Botsman, R.; Rogers, R. What’s Mine is Yours: How Collaborative Consumption is Changing the Way We Live; Collins: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Belk, R.W. You are what you can access: Sharing and collaborative consumption online. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1595–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardhi, F.; Eckhardt, G.M. Access-based consumption: The case of car sharing. J. Consum. Res. 2012, 39, 881–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifkin, J. The Age of Access: The New Culture of Cybercapitalism Where All of Life is a Paid-for Experience; Tarcher-Putman Books: New York, NY, USA, 2000; p. 228. [Google Scholar]

- Botsman, R.; Rogers, R. What’s Mine is Yours—The Rise of Collaborative Consumption? Harper Business: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, S.; Pennington, J. How Much is the Sharing Economy Worth to GDP? In World Economic Forum. 2016. Available online: www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/10/what-s-the-sharing-economy-doing-togdp-numbers/ (accessed on 1 September 2018).

- Agyeman, J.; McLaren, D.; Schaefer-Borrego, A. Sharing cities. Friends Earth Brief. 2013, 1–32. Available online: http://media.ontheplatform.org.uk/sites/default/files/agyeman_sharing_cities.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2013). [CrossRef]

- Phipps, M.; Ozanne, L.K.; Luchs, M.G.; Subrahmanyan, S.; Kapitan, S.; Catlin, J.R.; Weaver, T. Understanding the inherent complexity of sustainable Consumption: A social cognitive framework. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1227–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toni, M.; Renzi, M.F.; Mattia, G. Understanding the link between Collaborative Economy and sustainable behaviour: An empirical investigation. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 172, 4467–4477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, H.S.; Vergragt, P.J. From consumerism to well-being: Toward a cultural transition? J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 132, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, S.; Johnson, S. The happiness factor in tourism: Subjective well-being and social tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 41, 42–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, D.; Abdullah, J. Holiday taking and the sense of well-being. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, A.L.; Bitner, M.J.; Brown, S.W.; Burkhard, K.A.; Goul, M.; Smith-Daniels, V.; Demirkan, H.; Rabinovich, E. Moving forward and making a difference: Research priorities for the science of service. J. Serv. Res. 2010, 13, 4–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, A.L.; Parasuraman, A.; Bowen, D.E.; Patricio, L.; Voss, C.A. Service research priorities in a rapidly changing context. J. Serv. Res. 2015, 18, 127–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L.; Ostrom, A.L.; Corus, C.; Fisk, R.P.; Gallan, A.S.; Giraldo, M.; Shirahada, K. Transformative service research: An agenda for the future. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1203–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuppelwieser, V.G.; Finsterwalder, J. Transformative service research and service dominant logic: Quo Vaditis? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 28, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyle, M.; Crossland, J. The Dimensions of Positive Emotions. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 26, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannell, R. Social Psychological Techniques and Strategies for Studying Leisure Experiences. In Social Psychological Perspectives on Leisure and Recreation; Iso-Ahola, S., Ed.; Charles C. Thomas: Springfield, IL, USA, 1980; pp. 62–88. [Google Scholar]

- Haidt, J. The Happiness Hypothesis: Finding Modern Truth in Ancient Wisdom; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Guttentag, D. Airbnb: Disruptive innovation and the rise of an informal tourism accommodation sector. Curr. Issues Tour. 2015, 18, 1192–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veludo-de-Oliveira, T.M.; Ikeda, A.A.; Campomar, M.C. Discussing laddering application by the means-end chain theory. Qual. Rep. 2006, 11, 626–642. [Google Scholar]

- Felson, M.; Spaeth, J.L. Community Structure and Collaborative Consumption: A Routine Activity Approach. Am. Behav. Sci. 1978, 21, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schor, J. Debating the sharing economy. J. Self Gov. Manag. Econ. 2016, 4, 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Meelen, T.; Frenken, K. Stop Saying Uber Is Part of the Sharing Economy. Fast Co. 2015. Available online: https://www.fastcompany.com/3040863/stop-saying-uber-is-part-of-the-sharing-economy (accessed on 14 January 2015).

- Milanova, V.; Maas, P. Sharing intangibles: Uncovering individual motives for engagement in a sharing service setting. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 75, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botsman, R.; Capelin, L. Airbnb: Building a revolutionary travel company. In Said Business School Case; 2016; April 2015. (Revised January 2016); Available online: https://collaborativeeconomy.com/research/airbnb-building-a-revolutionary-travel-company/ (accessed on 29 April 2019).

- Tussyadiah, I.P. Factors of satisfaction and intention to use peer-to-peer accommodation. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 55, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeller, S.; Wittkowski, K. The burdens of ownership: Reasons for preferring renting. Manag. Serv. Qual. An Int. J. 2010, 20, 176–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittkowski, K.; Moeller, S.; Wirtz, J. Firms’ intentions to use nonownership services. J. Serv. Res. 2013, 16, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, M.; Kleinaltenkamp, M. Property rights design and market process: Implications for market theory, marketing theory, and SD Logic. J. Macromarketing 2011, 31, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenken, K.; Schor, J. Putting the sharing economy into perspective. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2017, 23, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tussyadiah, I.P. An exploratory study on drivers and deterrents of collaborative consumption in travel. In Information & Communication Technologies in Tourism; Tussyadiah, I., Inversini, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 817–830. [Google Scholar]

- Belk, R. Sharing versus pseudo-sharing in Web 2.0. Anthropologist 2014, 18, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrichs, H. Sharing economy: A potential new pathway to sustainability. GAIA Ecol. Perspect. Sci. Soc. 2013, 22, 228–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozanne, L.K.; Ballantine, P.W. Sharing as a form of anti-consumption? An examination of toy library users. J. Consum. Behav. 2010, 9, 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozanne, L.; Ozanne, J. A child’s right to play: The social construction of civic virtues in toy libraries. J. Public Policy Mark. 2011, 30, 264–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prothero, A.; Dobscha, S.; Freund, J.; Kilbourne, W.E.; Luchs, M.G.; Ozanne, L.K.; Thøgersen, J. Sustainable Consumption: Opportunities for consumer research and public policy. J. Public Policy Mark. 2011, 30, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The what and why of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self determination of behaviour. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellotti, V.; Ambard, A.; Turner, D.; Gossmann, C.; Demkova, K.; Carroll, J.M. A muddle of models of motivation for using peer-to-peer economy systems. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Seoul, Korea, 18–23 April 2015; pp. 1085–1094. [Google Scholar]

- Möhlmann, M. Collaborative consumption: Determinants of satisfaction and the likelihood of using a sharing economy option again. J. Consum. Behav. 2015, 14, 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J.; Sjöklint, M.; Ukkonen, A. The sharing economy: Why people participate in collaborative consumption. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2016, 67, 2047–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Towards the sustainable corporation: Win-win-win business strategies for sustainable development. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1994, 36, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamberton, C.P.; Rose, R.L. When is ours better than mine? A framework for understanding and altering participation in commercial sharing systems. J. Mark. 2012, 76, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgin, D. Voluntary Simplicity: Toward the Way of Life that is Outwardly Simple and Inwardly Rich; William Morrow and Company: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Schor, J.B. The Sharing Economy: Reports from Stage One. 2015. Unpublished Manuscript. Available online: http://www.bc.edu/content/dam/files/schools/cas_sites/sociology/pdf/TheSharingEconomy.Pdf (accessed on 15 November 2015).

- Barnes, S.J.; Mattsson, J. Building tribal communities in the collaborative economy: An innovation framework. Prometheus 2017, 34, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- See-To, E.W.; Ho, K.K. Value co-creation and purchase intention in social network sites: The role of electronic Word-of-Mouth and trust–A theoretical analysis. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 31, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albinsson, P.A.; Yasanthi Perera, B. Alternative marketplaces in the 21st century: Building community through sharing events. J. Consum. Behav. 2012, 11, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. J. Democr. 1995, 6, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, J.S. Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am. J. Sociol. 1988, 94, S95–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N. Building a network theory of social capital. Connections 1999, 22, 28–51. [Google Scholar]

- European Environment Agency. Well-Being and the Environment. Building a Resource-Efficient and Circular Economy in Europe. EEA Signals. 2014. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/signals-2014 (accessed on 15 May 2014).

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Savaget, P.; Bocken, N.M.; Hultink, E.J. The Circular Economy. A new sustainability paradigm? J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 143, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhzady, S.; Seyfi, S.; Béal, L. Peer-to-peer (P2P) accommodation in the sharing economy: A review. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M. Collaborative commerce in tourism: Implications for research and industry. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swig, R. Alt-Accommodation Impact Felt in San Francisco. 2014. Hotel News Now. Available online: http://www.hotelnewsnow.com/Articles/23683/Alt-accommodation-impact-felt-in-San-Francisco (accessed on 29 August 2014).

- Marques, L.; Gondim Matos, B. Network relationality in the tourism experience: Staging sociality in homestays. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 23, 1153–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulauskaite, D.; Powell, R.; Coca-Stefaniak, J.A.; Morrison, A.M. Living like a local: Authentic tourism experiences and the sharing economy. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 19, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Freitas Coelho, M.; De Sevilha Gosling, M.d.S.; De Almeida, A.S.A. Tourism experiences: Core processes of memorable trips. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2018, 37, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Cheng, M.; Wang, J.; Ma, L.; Jiang, R. The construction of home feeling by Airbnb guests in the sharing economy: A semantics perspective. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 75, 308–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.G.; Neuhofer, B. Airbnb–An exploration of value co-creation experiences in Jamaica. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tussyadiah, I.P.; Zach, F. Identifying salient attributes of peer-to-peer accommodation experience. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 34, 636–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, K.K.F.; Oh, H.; Min, S. Motivations and constraints of Airbnb consumers: Findings from a mixed-methods approach. Tour. Manag. 2018, 67, 224–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, R.; Muncy, J.A. Attitude toward consumption and subjective well-being. J. Consum. Aff. 2016, 50, 48–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittmar, H.; Bond, R.; Hurst, M.; Kasser, T. The relationship between materialism and personal well-being: A meta-analysis. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 107, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, P.S.; Kwon, S.W. Social capital: Prospects for a new concept. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.; Clay, P. Measuring subjective and objective well-being: Analyses from five marine commercial fisheries. Hum. Organ. 2010, 69, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, B.S.; Stutzer, A. What can economists learn from happiness research? J. Econ. Lit. 2002, 40, 402–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilovich, T.; Kumar, A. We’ll always have Paris: The hedonic payoff from experiential and material investments. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Zanna, M., Olson, J., Eds.; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Volume 51, pp. 147–187. [Google Scholar]

- Hornik, A.; Diesendruck, G. Extending the Self Via Experiences: Undermining Aspects of One’s Sense of Self Impacts the Desire for Unique Experiences. Soc. Cogn. 2017, 35, 181–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Alatartseva, E.; Barysheva, G. Well-being: Subjective and objective aspects. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 166, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. Subjective well-being. Psychol. Bull. 1984, 95, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huta, V.; Ryan, R.M. Pursuing pleasure or virtue: The differential and overlapping well-being benefits of hedonic and eudaimonic motives. J. Happiness Stud. 2010, 11, 735–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. Geographical consciousness and tourism experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 863–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. Vacations and the quality of life: Patterns and structures. J. Bus. Res. 1999, 44, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D.; Andreu, L.; Gnoth, J. The dark side of the sharing economy: Balancing value co-creation and value co-destruction. Psychol. Mark. 2020, 37, 689–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumazedier, J. Towards a Society of Leisure; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Filep, S. Moving beyond subjective well-being: A tourism critique. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawijn, J. Determinants of daily happiness on vacation. J. Travel Res. 2011, 50, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, N.; MacDonald, M.; Douthitt, R. Toward consumer well-being: Consumer socialisation effects of work experience. In New Dimensions of Marketing/Quality-of-Life Research; Quorum Books: Westport, CT, USA, 1995; pp. 151–175. [Google Scholar]

- Day, R.L. Beyond social indicators: Quality of life at the individual level. In The Marketing and the Quality of Life; American Marketing Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 1978; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, L.W.; Knight, T. Integrating the hedonic and eudaimonic perspectives to more comprehensively understand well-being and pathways to well-being. Int. J. Wellbeing 2012, 2, 196–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, T.J.; Gilovich, T. Getting the most for the money: The hedonic return on experiential and material purchases. In Consumption and Well-Being in the Material World; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Caprariello, P.A.; Reis, H.T. To do, to have, or to share? Valuing experiences over material possessions depends on the involvement of others. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 104, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorman-Murray, A. Materiality, masculinity and the home: Men and interior design. In Masculinities and Place; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 209–226. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh, V.; Brown, S.A.; Bala, H. Research article bridging the Qualitative—Quantitative Divide: Guidelines for conducting mixed methods. Mis Q. 2013, 37, 21–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluhm, D.J.; Harman, W.; Lee, T.W.; Mitchell, T.R. Qualitative research in management: A decade of progress. J. Manag. Stud. 2011, 48, 1866–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesse-Biber, S.; Johnson, R.B. Coming at Things Differently. J. Mixed Methods Res. 2013, 7, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.K.; Nunan, D.; Birks, D.F. Marketing Research an Applied Approach, 5th ed.; Prentice-Hall Inc.: Hoboken NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, J.J.; Johnston, M.; Robertson, C.; Glidewell, L.; Entwistle, V.; Eccles, M.P.; Grimshaw, J.M. What is an adequate sample size? Operationalising data saturation for theory-based interview studies. Psychol. Health 2010, 25, 1229–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urquhart, C. Grounded Theory for Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mayan, M.J. Essentials of Qualitative Inquiry; Leaf Coast Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, C.J. Interpreting Consumers: A Hermeneutical Framework for Deriving Marketing Insights from the Texts of Consumers’ Consumption Stories. J. Mark. Res. 1997, 34, 438–455. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Procedures and Techniques for Developing Grounded Theory; Saga Publication: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Barratt, M.; Choi, T.Y.; Lì, M. Qualitative Case Studies in Operations Management: Trends, Research Outcomes, and Future Research Implications. J. Oper. Manag. 2011, 29, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.K. Marketing Research. An applied Orientation; Pearson: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Tussyadiah, I.P.; Pesonen, J. Impacts of peer-to-peer accommodation use on travel patterns. J. Travel Res. 2015, 55, 1022–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolao, L.; Irwin, J.R.; Goodman, J.K. Happiness for sale: Do experiential purchases make consumers happier than material purchases? J. Consum. Res. 2009, 36, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradburn, N.M. The Structure of Psychological Well-Being; Aldine: Oxford, UK, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Bradburn, N.M.; Caplovitz, D. Reports on Happiness: A Pilot Study of Behaviour Related to Mental Health (No. 3); Aldine Publishing Company: Chicago, IL, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Grewal, R.; Mehta, R.; Kardes, F. The role of the social identity function of attitudes in consumer innovativeness and opinion leadership. J. Econ. Psychol. 2000, 21, 233–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Cass, A. A psychometric evaluation of a revised version of the Lennox and Wolfe revised self-monitoring scale. Psychol. Mark. 2000, 17, 397–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthen, L.; Muthen, B. MPLUS: Users’ Guide; Muthen & Muthen: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Reisinger, Y.; Turner, L. Structural equation modeling with Lisrel: Application in tourism. Tour. Manag. 1999, 20, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, M.Y.; Jackson, J.D.; Park, J.S.; Probst, J.C. Understanding information technology acceptance by individual professionals: Towards an integrative view. Inf. Manag. 2006, 43, 350–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisinger, Y.; Mavondo, F. Structural equation modeling: Critical issues and new developments. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2007, 21, 41–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Colby, C.L. An updated and streamlined technology readiness index TRI 2.0. J. Serv. Res. 2015, 18, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liébana-Cabanillas, F.; Sánchez-Fernández, J.; Muñoz-Leiva, F. Antecedents of the adoption of the new mobile payment systems: The moderating effect of age. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 35, 464–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NU, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to under-parameterised model misspecification. Psychol. Methods 1998, 3, 424–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Modeling a Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M. EQS Structural Equations Program Manual; Multivariate Software: Encino, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Maciejewski, G. Consumers Towards Sustainable Food Consumption. Mark. Sci. Res. Organ. 2020, 36, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constructs | Items Number | Reference | Measurement Scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Economic dimension | 3 | [51,52,110] | Likert scale (1 = completely disagree to 7 = completely agree) |

| Social dimension | 3 | [110] | Likert scale (1 = completely disagree to 7 = completely agree) |

| Environmental dimension | 3 | [51,52] | Likert scale (1 = completely disagree to 7 = completely agree) |

| Attitude towards P2P accommodation service | 5 | Qualitative results and [69,72,73] | Likert scale (1 = completely disagree to 7 = completely agree) |

| Subjective well-being | 5 | Qualitative results and [111,112,113] | Likert scale (1 = completely disagree to 7 = completely agree) |

| Factor | Cronbach’s Alpha >0.7 Nunnally, 1978 [122] | AVE >0.5 Fornell and Larcker, 1981 [123] | CR >0.7 Fornell and Larcker, 1981 [123] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Economic dimension (F1) | 0.824 | 0.613 | 0.826 |

| Social dimension (F2) | 0.813 | 0.593 | 0.814 |

| Environmental dimension (F3) | 0.845 | 0.644 | 0.844 |

| Attitude towards P2P accommodation service (F4) | 0.882 | 0.563 | 0.866 |

| Subjective well-being (F5) | 0.944 | 0.779 | 0.946 |

| Goodness-of-Fit-Index | Observed Value | Commonly Used Threshold |

|---|---|---|

| χ2 (chi-square) Degrees of freedom p-value | 4425.809 171 0.000 | |

| RMSEA (root mean square error of approximation) | 0.077 | <0.05 → minimal error 0.05 ≤ RMSEA ≤ 0.08 → acceptable 0.08 → rejected the model |

| SRMR (standardised root mean square residual) | 0.067 | <0.08 (Hu e Bentler, 1998, 1999) [124,125] |

| CFI (comparative fit index) | 0.915 | ≥0.90 (Bentler, 1992) [126] |

| Hypotheses | Predictor | Dependent | Estimate | p-Value | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Economic dimension | Attitude towards P2P accommodation service | 0.129 | 0.009 | supported |

| H2 | Social dimension | Attitude towards P2P accommodation service | 0.659 | 0.002 | supported |

| H3 | Environmental dimension | Attitude towards P2P accommodation service | 0.242 | 0.003 | supported |

| H4 | Attitude towards P2P accommodation service | Subjective Well-being | 0.511 | 0.000 | supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Toni, M.; Renzi, M.F.; Di Pietro, L.; Guglielmetti Mugion, R.; Mattia, G. The Relation between Collaborative Consumption and Subjective Well-Being: An Analysis of P2P Accommodation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5818. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13115818

Toni M, Renzi MF, Di Pietro L, Guglielmetti Mugion R, Mattia G. The Relation between Collaborative Consumption and Subjective Well-Being: An Analysis of P2P Accommodation. Sustainability. 2021; 13(11):5818. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13115818

Chicago/Turabian StyleToni, Martina, Maria Francesca Renzi, Laura Di Pietro, Roberta Guglielmetti Mugion, and Giovanni Mattia. 2021. "The Relation between Collaborative Consumption and Subjective Well-Being: An Analysis of P2P Accommodation" Sustainability 13, no. 11: 5818. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13115818

APA StyleToni, M., Renzi, M. F., Di Pietro, L., Guglielmetti Mugion, R., & Mattia, G. (2021). The Relation between Collaborative Consumption and Subjective Well-Being: An Analysis of P2P Accommodation. Sustainability, 13(11), 5818. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13115818