This section encompasses the proposed set of indices for assessing global democracy, the analysis of the correlations and interdependencies between global indicators related to sustainability and democracy, and the proposed concept of Regenerative Democracy and its respective system dynamics modeling archetype.

3.1. Assessing Global Democracy—Crisis, Stability, and Transitioning Regimes

The transitions from non-democratic to democratic systems that occurred around the world over the past two centuries represent one of the great societal transformations in history. Assembling historical data from Polity IV [

26],

Figure 1 depicts, from 1800 to 2018, Polity IV’s global democracy index (GDI

PIV); the global percentage index (GPI

PIV), which is proposed to quantify the percentage of states with democratic features; and the relative difference index (RDI

PIV), which is proposed to quantify the difference between the values of GDI

PIV and GPI

PIV. Aiming at comprehensiveness, Polity IV’s categories of open anocracies (i.e., mixed and/or incoherent democratic systems), democracies (i.e., institutionalized democratic systems), and full democracies (i.e., fully institutionalized and consolidated democratic systems) are equally considered. To enable comparison, all indices are normalized on a scale of 0 to 1.00. RDI

PIV is conceived to assess the balance between the quantity of states with democratic features and overall quality of democracy in the world. The index RDI

PIV is conceived to vary on a scale of −1.00 to 1.00, in which RDI

PIV = 0 specifies the balancing point between GDI

PIV and GPI

PIV. In this context, the lower the value of RDI

PIV within the range of −1.00 to 0 and the higher the value of RDI

PIV within the range of 0 to 1.00, the more unbalanced the relationship between GDI

PIV and GPI

PIV.

As depicted in

Figure 1, GDI

PIV increased from 0.17 in 1800 to 0.72 in 2018. Following a similar behavioral pattern, GPI

PIV increased from 0.09 (i.e., 9.0%) in 1800—including two open anocracies and no democracies out of 22 states—to 0.71 (i.e., 71.0%) in 2018, including 20 open anocracies, 66 democracies, and 32 full democracies out of 166 states (therefore over half the world population). From 1800 to 2018, GDI

PIV exhibited a very high positive correlation with GPI

PIV (i.e., Pearsons’s coefficient

r = 0.99) and RDI consistently decreased for higher values of GDI

PIV, therefore suggesting a high interdependence between the quantity of states with democratic features and overall quality of democracy in the world. These results suggest that historically, snowball effects are major driving forces for democratization. In this regard, the political choices of one specific state may significantly affect the political choices and actions of neighboring states.

In light of the proposed indices, key milestones regarding crises, stability, and transitioning regimes of global democracy are assessed and discussed as follows. Historically, the American (1765–1783) and French (1789–1799) revolutions cast the essentials for the long and widespread first wave of democratization (1828–1926), disrupting systems of privilege as well as political and legal foundations of the old order [

17]. Following the breakup of the Austrian (1804–1867), Russian (1721–1917), German (1871–1918), and Ottoman (1299–1923) empires, and the outcomes of the World War I (1914–1918), monarchies disappeared, continental empires crumbled, and a mass movement towards democracy spread across Europe [

16]. As depicted in

Figure 1, from the beginning of the first wave of democratization in 1828 to its end in 1926, GDI

PIV increased from 0.24 to 0.57, GPI

PIV increased from 0.09 to 0.49, and RDI

PIV decreased from 0.14 to 0.08. The number of states with democratic features increased from three open anocracies and one democracy to 12 open anocracies, nine democracies, and 15 full democracies. First reversals include the rise of fascism and national socialism in Italy (1922-1943) and the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (Nazism) in German (1933-1945), leading to the upsurge of pervasive and militaristic dictatorships [

16,

17]. These struck recently formed democracies that could not resist dictatorship’s expansionist actions. After more than a century of democratic achievements, at the end of the first reversals in 1942, GDI

PIV decreased to 0.43, GPI

PIV decreased to 0.25, and RDI

PIV increased to 0.18. The number of states with democratic features decreased to nine open anocracies, one democracy, and eight full democracies.

Following the allied victory in World War II (1939–1945), the second wave of democratization (1943–1962) occurred [

17]. Post-war, the authority of the old order was more thoroughly disrupted than any time since the French and American revolutions and many barriers for democratic transitions and consolidation notably diminished [

16,

17]. Radical right ideologies were undermined and class structures, status hierarchies, and social norms transformed. A common understanding of the interdependent relationship between states, markets, and societies was finally acknowledged [

16]. In this regard, more homogenous, peaceful, and stable nation-states emerged, inaugurating a new geopolitical order. As depicted in

Figure 1, from the beginning of the second wave of democratization in 1943 to its end in 1962, GDI

PIV increased from 0.44 to 0.49, GPI

PIV increased from 0.25 to 0.40, and RDI

PIV decreased from 0.19 to 0.09. The number of states with democratic features increased from nine open anocracies, one democracy, and eight full democracies to 11 open anocracies, 14 democracies, and 22 full democracies. Nevertheless, by the early 1960s the second wave of democratization had exhausted its strength, mainly with dramatic transitions towards authoritarian players in Latin America [

17]. Second reversals produced a broader skepticism on the applicability of democracy in developing economies as well as a strong pessimism on its workability among the developed economies where it had existed for years [

17]. After a short period of democratic achievements, at the end of the second reversals in 1975, GDI

PIV decreased to 0.41 and GPI

PIV decreased to 0.32. The number of states with democratic features decreased to 9 open anocracies, 15 democracies, and 21 full democracies. RDI

PIV exhibited a relatively steady behavior since the apex in 1957 (i.e., RDI

PIV = 0.09), suggesting that reversals impacted both the quantity and the quality of democratic features in a coherent manner.

The third wave of democratization differed from those of earlier waves. The transitions towards democracy were pervasively strong, significantly outnumbering transitions in the opposite direction [

16,

17]. Following the Carnation Revolution that marked the end of the Portuguese dictatorship in 1974, democratic systems replaced authoritarian ones in several states in Europe, Asia, and Latin America [

17]. The global economic and technological development of the 1950s and 1960s greatly raised living standards, increasing education, expanding the urban middle class in many states, advancing technology, and boosting cultural and geopolitical relationships [

17]. At this point, the ideals of democracy were widely desired and many social movements emerged around the world, fostering democracy’s strength and legitimacy. The fall of the Berlin Wall (1989), the collapse of the Soviet Union (1991), and the end of the apartheid regime in South Africa (early 1990s) furthered a widespread perception of democracy as a common goal for the future [

17].

Figure 2 portrays the indices for assessment of global democracy from 1972 to 2018. In

Figure 2, the global democracy index, GDI

FH, and global percentage index, GPI

FH, are quantified based on data from Freedom House [

28]; the global democracy index, GDI

BT, and global percentage index, GPI

BT, are quantified based on data from the Bertelsmann [

23]; and the global democracy index, GDI

EIU, and global percentage index, GPI

EIU, are quantified based on data from the Economist Intelligence Unit [

21]. Aiming to perform an integrative analysis in light of more recent data, the overall averages for the global democracy index (GDI), global percentage index (GPI), and relative difference index (RDI) are also quantified and depicted in

Figure 2.

As depicted in

Figure 1 and replicated with a more detailed silhouette in

Figure 2, both GDI

PIV and GPI

PIV reached the highest value of 0.72 in 2013—including 25 open anocracies, 59 democracies, and 34 full democracies. As portrayed in

Figure 2, the highest values for the following indices were GDI

FH = 0.62 in 2005 and GPI

FH = 0.80 in 1992—including 74 free states and 72 partially free states; GDI

BT = 0.58 in 2008 and GPI

BT = 0.91 in 2010—including 40 defective democracies, 36 democracies in consolidation, and 42 highly defective democracies; and GDI

EIU = 0.56 in 2015 and GPI

EIU = 0.86 in 2014—including 53 flawed democracies, 45 full democracies, and 42 hybrid regimes. The highest average value for GDI was 0.66 in 2005, which decreased to 0.60 in 2018, and for GPI was 0.81 in 2013, which slightly decreased to 0.80 in 2018.

As depicted in

Figure 2, from the beginning of the third wave of democratization in 1974 to 2018, GDI increased from 0.44 to 0.60 and GPI increased from 0.46 to 0.80. With a critical turning point in 2006, RDI consistently decreased from 0.01 in 1972 to −0.20 in 2018. These results indicate a gradual decoupling between GDI and GPI, therefore signifying an increasingly unbalanced relationship between the quantity of states with democratic features and the overall quality of democracy. It is noteworthy that a comparable magnitude for RDI in 2018 was last observed in 1867. Additionally, from 1972 to 2005, GDI exhibited a very high positive correlation with GPI (

r = 0.98) and from 1972 to 2018, RDI exhibited a high negative correlation with GDI (

r = −0.62) and a very high negative correlation with GPI (

r = −0.88). These findings indicate an overall trend and potential phase of democratic instability, comprising a persistent lack of quality distribution in the democratic systems and increasing risk of democratic systems degeneration. Aiming to synthesize the main results and discussion of this section,

Figure 3 depicts the indices for the assessment of global democracy for key historical milestones of democratization.

In alignment with these findings, the most recent report, “Freedom in the world 2020—a leaderless struggle for democracy” [

28], recently specified that the number of states that suffered democratic setbacks in 2019 exceeded those making achievements by nearly two to one, marking the 14th consecutive year of crisis. In this report, the functioning of government, the freedom of expression and belief, and the rule of law were identified as the main domains of decline and an alarming global erosion in the governments’ commitment to democratic pluralism was noted. The quality and stability of democracy declined in several large and strategically important emerging-market states. A total of 25 of the world’s 41 established democratic states experienced net losses, lacking vigor and self-confidence to effectively promote democracy domestically and abroad.

According to the EIU’s report “Democracy Index 2019—a year of democratic setbacks and popular protest” [

21], from 2006 to 2019 the GDI

EIU for Western Europe decreased from 0.86 to 0.83 and for the United States from 0.82 to 0.79. In 2019, only 5.7% of the world’s population was living in full democracies and more than a third were still living with civil liberties constraints under authoritarian systems. The main evidence of this democratic recession includes an increasing emphasis on elite governance rather than popular participatory democracy; a growing influence of unelected, unaccountable institutions and expert bodies; the removal of substantive issues of national importance from the political arena to instead be decided by politicians, experts, or supranational bodies behind closed doors; a widening gap between political elites and national electorates; and a decline in civil liberties, including media freedom and freedom of speech. From 2008 to 2019, the average scores for four out of five categories of GDI

EIU decreased significantly and almost sequentially. The worst-performing category was civil liberties (declining from 0.64 to 0.57), followed by electoral process and pluralism (from 0.60 to 0.58), functioning of government (from 0.50 to 0.48), and political culture (from 0.575 to 0.55). Enhanced by widespread protests around the world, political participation was the only category that exhibited an upward global trajectory, increasing from 0.464 to 0.53. Except for North America, whose average score for political participation decreased from 0.78 in 2011 to 0.75 in 2019, every region recorded an improvement in this category. This societal movement underscores the emergence of an interconnected desire for justice, equality, freedom, good governance, and societal transformative changes.

3.2. Correlations and Interdependencies between Global Sustainability and Democracy

The global transformational achievements that have occurred throughout the third wave of democratization were largely propelled forward by economic and technological progress [

17]. Key evidence indicates that not only has the world’s population living in extreme poverty dropped significantly, but also that individuals are healthier today than ever before [

11,

12,

30,

31]. People are benefiting from unprecedented opportunities to achieve not only their basic needs but also material comfort, convenience, emancipation, and joy [

31,

32]. To grasp the magnitude of these achievements, it suffices to examine the correlational features and trends of a set of key global indicators related to essential societal needs. In this regard,

Table 1 displays the quantified empirical correlation coefficients associated with each global indicator examined in this study. In

Table 1, correlation coefficients are quantified against one another and outlined according to the Doughnut Economics framework [

3,

4] and Sustainable Development Goals [

11,

12].

The world’s population rapidly increased from around 2.6 billion people in 1950 to 3.7 billion people in 1970 and 7.7 billion people in 2020 [

33]. Acknowledged as an essential indicator for assessing societal prosperity and well-being, the life expectancy at birth (LE) increased globally from around 45.0 years in 1950 to 57.0 years in 1970 and 72.0 years in 2020 [

33,

34]. It is important to point out that the LE linked to citizens in democratic states is on average six years longer than for non-democratic ones. From the beginning of the third wave in 1974 until 2018, the global GDP increased from 5.3 to USD 87.8 trillion and the GDP per capita (GDP) increased from USD 1.3 to 11.4 thousand [

33]. In comparison to indices related to global democracy, the average annual growth rate for the global GDP was consistently higher (around 3.0%) than for the global population (1.5%), and the average annual growth rate for GPI was consistently higher (around 1.30%) than for GDI (0.70%). During this time, the national income per capita for adults (NI) increased from around USD 6000 to 16,000 (converted by purchasing power parity at a 2018 constant dollar), providing a very substantial improvement in the overall living standards and human well-being [

31].

The poverty headcount ratio at USD 1.90 a day (PO) decreased from 42.3% to 10.0% of the world population from 1981 to 2015 [

33]. The prevalence of underweight children under the age of five (UC) decreased from 24.9% in 1990 to 13.0% in 2019 [

33,

34]. The percentage of the world population using basic sanitation (BS) increased from 55.4% in 2000 to 73.4% in 2017 [

34]. The prevalence of the undernourished world population (UP) decreased from 18.5% in 1991 to 10.8% in 2017 [

34]. The percentage of the world population with access to clean fuels and technologies for cooking (CT) increased from 49.4% in 2000 to 59.4% in 2016 [

34]. The percentage of the world population with access to electricity (AE) increased from 72.6% in 1998 to 89.6% in 2018 [

34]. The literacy rate—aged 15 or higher (LR) increased from 65.2% in 1976 to 86.3% in 2018 [

33]. The number of children out of school (CS) decreased from 28.3% in 1970 to 8.1% in 2018 [

33,

34]. The number of adolescents out of secondary school (AS) decreased from 26.0% in 1998 to 15.5% in 2018 [

33,

34]. The number of scientific and technical journal articles (JA) doubled from 2000 to 2016 [

33]. The number of patent applications including residents and nonresidents (PA) quadrupled from 1985 to 2016 [

33]. The percentage of the world population with access to the internet (AI) increased from almost 0 in 1990 to 49.7% in 2016 [

33]. Although gender parity in society is still far from being achieved, the gender parity for literacy—aged from 15 to 24 (GP), which assesses the ratio of females to males that can both read and write—increased from 0.83 in 1975 to 0.97 in 2018 and the number of seats held by women in national parliaments (SW) increased from 11.7% in 1997 to 24.6% in 2019 [

33,

34].

In

Table 1, except for the results associated with NI [

31,

35] for the top 1.0% of earners (NI:1), top 10.0% (NI:10), middle 40.0% (N:40), and bottom 50% (NI:50), all correlation coefficients quantified for the relationships between the global indicators that change in the same direction, either achieving or failing essential needs, are positive and categorized as very high (i.e.,

). Correspondingly, all correlation coefficients quantified for the relationships between the global indicators that change in the opposite direction, either achieving or failing essential needs, are negative and also categorized as very high (i.e.,

). These findings indicate a clear dominance of a highly interdependent relationship between the global indicators related to essential needs. Therefore, through an integrated web of feedback loops, societal achievements significantly increase the likelihood of more ubiquitous achievements, and societal failures significantly increase the likelihood of more ubiquitous failures.

Concerning the indices related to global democracy (discussed in

Section 3.1), GDI exhibited a very high and high positive correlation (i.e.,

) with LE, GDP, NI, NI:1, NI:10, NI:50, UP, LR, PA, GP, EF, and CF; a very high and high negative correlation (i.e., −

) with NI:40, PO, UC, BS, CT, CS, and JA; a low negative correlation (

) with SW; and a low positive correlation (

with AE, AS, and AI. Encompassing only high and very high coefficients, GPI exhibited a positive correlation with LE, GDP, NI, NI:1, NI: 10, NI:50, BS, CT, AE, LR, JA, PA, AI, GP, SW, EF, and CF and a negative correlation with NI:40, PO, UC, UP, CS, and AS. Finally, RDI exhibited a very high and high positive correlation with NI:40, PO, UC, UP, CS, and AS; a very high and high negative correlation with LE, GDP, NI, NI:1, NI:50, BS, CT, AE, LR, JA, PA, AI, GP, SW, EF, and CF; and a low negative correlation with NI:10.

By contrast, changing in an opposite direction from achieving essential needs, GDI exhibited a very high negative correlation with NI:40, CT, BS, and JA and a high positive correlation with UP, EF, and CF. Furthermore, GPIA exhibited a very high negative correlation with NI:40 and a very high positive correlation with EF and CF. RDI exhibited a high positive correlation with NI:40 and a very high negative correlation with EF and CF.

These results reveal a highly interdependent relationship between historical achievements of essential societal needs and global democratic stability and consolidation. Therefore, they suggest that the lower the achievement of essential societal needs for all, the lower the achievement of democratic stability and consolidation. Furthermore, based on the results for national income distribution NI:1, NI:10, NI:40, and NI:50 and ecological and carbon footprints EF and CF, it is clear that inequality, ecological degradation, and climate crisis are the primary challenges regarding how societies have operated globally.

Inequality is disruptive and reveals the structural hierarchy in which the class system is formed and societal outcomes occur [

32]. Beyond a certain point, inequality undermines the legitimacy and stability of democracy, mainly if well-resourced minorities get disproportionate control over the institutions and political process as a result of their wealth [

14]. Based on historical data, global society experienced a phase of relative equality from 1950 to 1980, subsequently transitioning toward the inegalitarian realm [

31]. Except in highly inegalitarian states, inequality has increased in practically every state of the world since 1980 [

31,

35]. As summarized in

Table 1, the correlation between GDI

A and NI:40 is negative and very high and the correlation between GDI

A and N:1 and GDI

A and NI:10 is significantly higher than the correlation between GDI

A and NI:50.

From 1980 to 2018, large fortunes increased at growth rates four times higher than the global economy [

31]. Particularly, this rapid increase came at the expense of the bottom 50.0% of earners, in which the share of the total income distribution significantly decreased from about 25.0% in 1980 to 15.0% in 2018 [

31]. The share of national income distribution of the highest 10.0% of earners significantly increased, ranging from 26.0% to 34.0% in 1980 and from 34.0% to 56.0% in 2018 [

31]. Particularly, it ranged from 28.0 to 34.0% in Europe, from 27.0 to 41.0% in China, from 26.0 to 46.0% in Russia, from 34.0 to 48.0% in the United States, and from 32.0 to 55.0% in India [

31]. From 1980 to 2018, the top 1.0% captured 27.0% of the global income growth, exhibiting a substantial growth in purchasing power varying from 80.0% to 240.0%, whereas the bottom 50.0% captured only 12.0% of the global income growth, exhibiting a growth in purchasing power varying from 60.0% to 120.0% [

31,

35]. Summarily, income inequality decreased between the bottom and middle of the income distribution and increased between the middle and the top.

Measured in units of Planet Earth, from 1974 to 2016, the global ecological footprint (EF) increased from 1.06 to 1.69 and the global carbon footprint increased from 0.57 to 1.01, clearly indicating a life-threatening resilience decline at a planetary scale [

36]. Particular to the climate crisis, from 1990 to 2105, the bottom 50.0% of the world’s population (i.e., 3.1 billion people) was responsible for 7.0% of cumulative CO

2eq emissions added to the atmosphere and accounted for 4.0% of the available global carbon budget defined by the Paris Agreement’s 1.5 C goal [

37,

38]. By contrast, the middle 40.0% (i.e., 2.5 billion people) was responsible for 41.0% of the cumulative CO

2eq emissions and accounted for 25.0% of the global carbon budget [

37]. The top 10.0% (i.e., 630 million people) was responsible for 52.0% of cumulative CO

2eq emissions and accounted for 31.0% of the global carbon budget [

37]. The top 1.0% (i.e., 62 million people) was responsible for 15.0% of cumulative CO

2eq emissions and accounted for 9.0% of the global carbon budget, twice as much as the poorest half of the world population [

37].

The carbon footprint (CF) per capita of the richest 10.0% was more than 30 times greater than for the poorest 50.0% and more than 10 times greater than the target defined by the Paris Agreement’s 1.5 C goal [

36]. Around half the emissions of the richest 10% (i.e., 24.5% of global emissions) are associated with citizens of North America and Europe and only a fifth (i.e., 9.2% of global emissions) with citizens of China and India [

38]. Around 35.0% of the CO

2eq emissions of the richest 1.0% are today linked to citizens in the United States [

38]. The emissions related to the top 1.0% and 10.0% are mainly produced by excessive consumption patterns as well as the growing usage of sport utility vehicles (SUVs) and private flights [

38]. Although half the world’s population still earned less than USD 5.50/day in 2015, the carbon footprint per capita in the top 1.0% was more than 100 times greater than for the bottom 50.0% and 35 times greater than the Paris Agreement’s 1.5 C goal. The global carbon budget is being rapidly depleted, regrettably not for the purpose of lifting all humans in the world to a safe and fair living standard, but to a large extent to expand the material consumption and convenience of the world’s very richest people.

The overall findings of this section call attention to the issue of governance, particularly to the form of local, national, and global governance that might maintain or enhance democracy. It is well known that the quality of democracy is not exclusively determined by the quality of government. However, when democratic governments fail to meet the expectations of some individuals, they may become unwilling to acknowledge the legitimacy of democracy in itself. The growth of an anti-democratic culture is a major threat to democracy [

17,

20]. It impedes the spread of democratic values and practices, denies legitimacy to democratic leaders and institutions, and notably disrupts the stability of democratic systems. Furthermore, when societal rules are not equitably functioning, individuals may believe that they are designed by the elite and primarily for the elite [

39]. It is imperative to promote democracy for all people, proactively fostering tolerance and collaboration, egalitarian structures between and within multilateral groups, political pluralism, and a deep desire to transition to higher and innovative stages of democracy.

More complex economies are more adaptable, transformative, and persistent than less complex ones [

40,

41,

42]. Economic complexification may thus be pointing towards societal resilience and new ways of acting, producing, relating, and valuing. The achievement of economic complexity has been neither ubiquitous nor egalitarian. States whose degree of economic complexity is greater than expected regarding their level of national income per capita, usually grow faster than those that are overly wealthy when compared to their current degree of economic complexity [

43,

44]. Currently, the highest degrees of economic complexity belong to democratic states and, as a general rule, all democratic states are gradually reaching a more complex and wealthier economy [

44].

Although it is feasible for new and more sophisticated forms of non-democratic systems to emerge, it is increasingly difficult for authoritarian forces to act and control an information-mastered, scientific-based, and hyperconnected technological society. When a certain level of economic complexity is achieved, states move to a shifting zone where their likelihood to transition in a democratic direction increases significantly [

15,

17]. The greater the economic complexity and wealth distribution, the more knowledgeable the society and the better the conditions for the long-term perspective of democracy [

41]. Economic complexity reflects the diversity of productive knowledge embedded in industrialized societies [

43,

44]. Increasing productive knowledge in a society involves enlarging interconnectivity. Societies function through interdependent operational webs that allow individuals to collectively produce, use, and share large amounts of specialized knowledge and resources.

Societal progress may have made democracy achievable; however, it is interpersonal trust, political participation, and transformative leadership that makes it realistic. A democratic state is founded and upheld by individuals and political leaders who believe in the transition to a desirable democratic world and have the courage to challenge the status quo and subordinate the immediate interests to longer-term democracy. For democratic states to come into being and consistently endure, individuals must envision the long-lasting effects of democracy and cultivate their sense of belonging to a democratic society. They also must create and activate transformative change, and dismantle the way that authoritarian behaviors manifest within themselves, communities, and society as a whole. As a way of living, the ideals of democracy compel enlarged thinking and sympathy to the condition of others within as well as across borders.

Inequality is a forceful social divider, disconnecting government from citizens, rich from poor, minority from majority, people from humanity, and humans from nature. Evidence shows that reducing inequality is an effective way to improve the quality of societal systems, and therefore the real quality of life for all [

32,

45]. Higher equality fosters a greater sense of collaboration and intergenerational responsibility, which is essential for furthering a culture of regenerative change [

6]. High levels of equality and well-being within a society shape the ideals, aspirations, and attitudes of its citizens. In the long run, differences in material access gradually become overlaid by differences in education, aesthetic taste, sense of self, and all the other markers of class identity and social belonging [

32]. Furthermore, societies with higher equality exhibit lower ecological and carbon footprints, produce less waste, consume less, and fly less per capita [

32,

36].

3.3. Regenerative Democracy for Envisioning and Fostering Flourishing Societies

In light of cutting-edge discussions aimed at fostering democratic societies vis-à-vis the challenges posed by global sustainability, the concept of Regenerative Democracy and its respective system dynamics modeling archetype is conceived.

Regenerative Democracy is a political systems design that aims for the achievement of long-lasting flourishing societies through social equity, political participation, intergenerational solidarity, and synergistic relationships between societies and Earth’s life-giving systems. Combining democratic ideals with essential precepts for global sustainability, Regenerative Democracy is also a vision that brings hope for regenerative societal change towards desirable futures, magnifying the sense of being part of and contributing to a meaningful and inclusive purpose of liberty, equality, and fraternity. Within Regenerative Democracy, institutions represent the interests of current and future generations and civil society participates in the creation of policies on long-term issues in order to ensure intergenerational rights and well-being for all as well as to safeguard and restore Earth’s life-giving systems. Civil liberties and fundamental political freedoms are not only respected but also reinforced by a political culture conducive to the thriving of regenerative democratic principles and practices. Regenerative democratic leaders are selected through free, accessible, fair, transparent, and periodic elections in which candidates freely and equally compete for votes and all of the adult population is eligible to vote. Leaders are prepared to address global-scale problems with multi- and intergenerational thinking.

Aiming to portray societal scenarios in broad evolutionary contours, the Regenerative Democracy system dynamics modeling archetype is also proposed and depicted in

Figure 4. This archetype is modeled to provide meaningful insights regarding the essential preconditions that would enable global society to transition from non-democratic states to democratic states and regenerative democratic states. It is proposed as a modeling tool to examine why, how, and when transitions occur, and what makes them produce desirable outcomes.

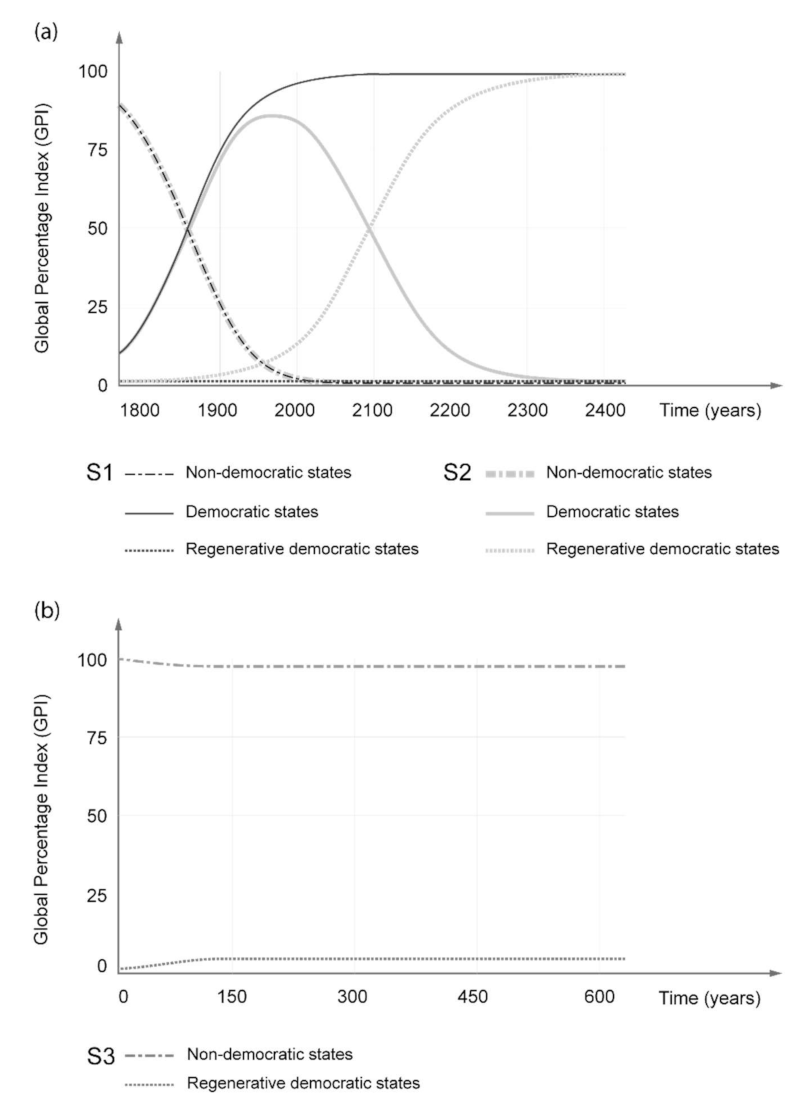

In light of the results and discussion from

Section 3.1 and

Section 3.2, three key scenarios (i.e., S1: the utopic world, S2: the transitioning world, and S3: the perilous world) are simulated and portrayed in

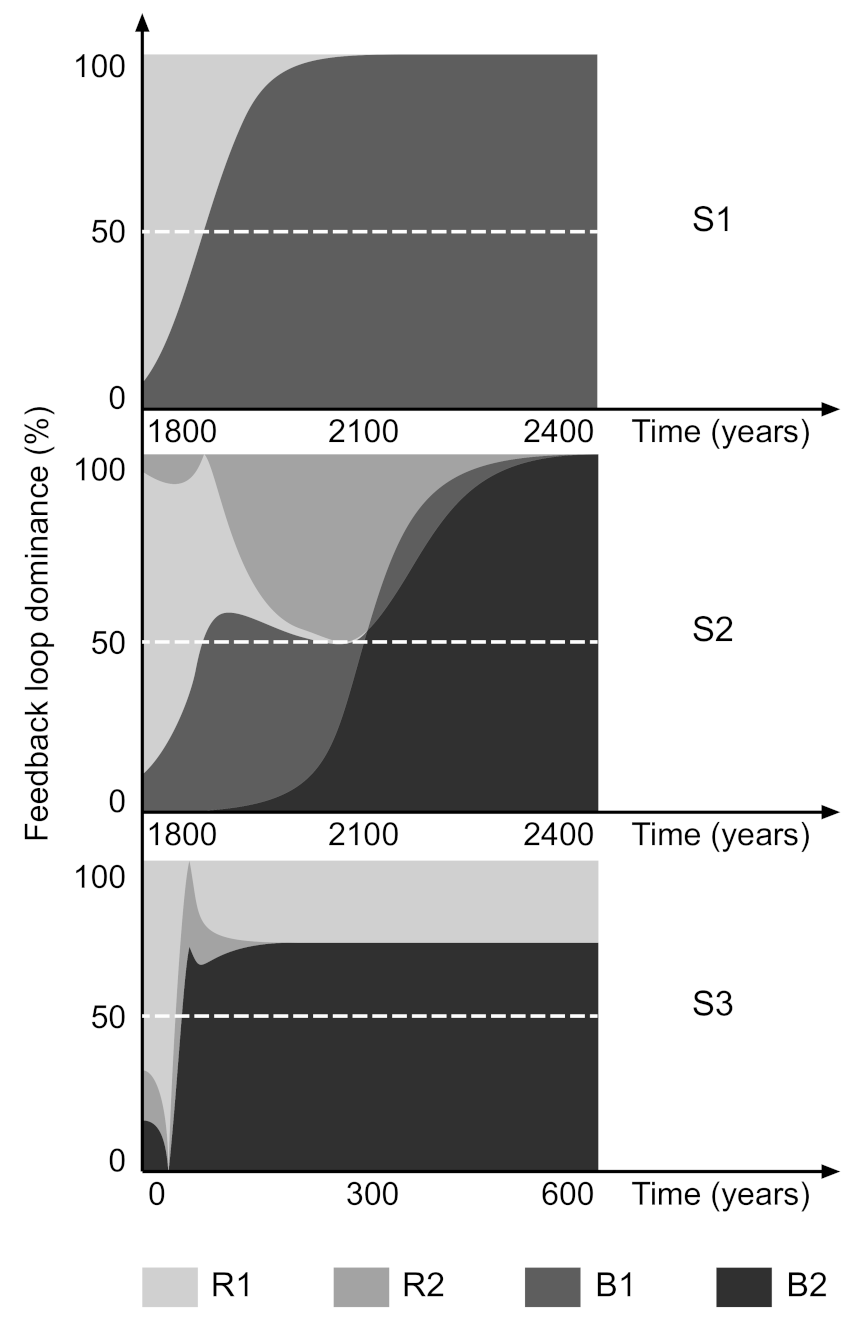

Figure 5 and their associated feedback loop dominance over time is depicted in

Figure 6. In these simulations, the initial value of the stock “non-democratic states” was equal to GPI

PIV = 0.91 in 1800 for S1 and S2 and assumed to be 0.99 for S3. The initial value of the stock “democratic states” was equal to GPI = 0.80 in 2018 for S1 and S2 and assumed to be 0.1 for S3. For the sake of mathematical consistency, the initial value of the stock “regenerative democratic states” was assumed to be 0.01 for all scenarios.

Enabling the examination of potential reversals, both flows are defined as bi-directional flows. The flow “states transitioning to democracy” is calculated by multiplying the converters “likelihood of spreading democratic principles and practices” and “engaging contacts between democratic states and non-democratic states.” The flow “states transitioning to regenerative democracy” is calculated by multiplying the stock “regenerative democratic systems” and the converters “likelihood of spreading regenerative democratic principles and practices” and “socio-ecological challenges.”

According to the overall average rate for all indicators displayed in

Table 1, the converter “societal and democratic achievements” was estimated to be 1.5%. Based on the average growth rate for GDI from 1972 to 2018, the converters “likelihood of spreading democratic principles and values” was estimated to be 0.9%. In light of historical trends and current achievements, the converters “societal and regenerative democratic achievements” were also assumed to be 1.5% and the converters “likelihood of spreading regenerative democratic principles and values” was also assumed to be 0.9%. The converters “not engaged fraction of non-democratic states” and “not engaged fraction of democratic states” were quantified by dividing the values by the total number of states.

Based on the value of GPI = 0.80 in 2018, the converters “effective contacts per state per year” was gauged as 34.0% for all scenarios and the converters “lack of achievement rate” and “transgression rate” were both gauged as 0.6% for S2 and S3 and assumed to be 0 for S1. The converters “contacts per year” was calculated by multiplying the converters “effective contacts per state per year” and the stock “democratic systems.” The converters “engaging contacts between democratic states and non-democratic states” was quantified by multiplying the converters “not engaged non-democratic states” and “contacts per year.” Aiming at an unbiased examination, the converters “lack of commitment to regenerative democracy” was assumed to be 50.0%. The converters “socio-ecological challenges” were estimated by multiplying the converters “not engaged democratic states,” “transgression of planetary boundaries,” “lack of achievement of essential needs for all,” and “lack of commitment to regenerative democracy.” Given that the univocal measurement of the social and ecological limiting factors is beyond the scope of this study, the lack of achievements of essential needs for all and the transgression of planetary boundaries were assumed to be equally important (i.e., with the same weighting factor).

Scenario S1—the utopic world: This describes a societal scenario in which there is no lack of achievement of essential needs and no transgression of planetary boundaries. As portrayed in

Figure 5a, GPI associated with the stock “non-democratic states” rapidly decreased from 0.91 in 1800 to zero in 2150, whereas GPI associated with the stock “democratic states” rapidly increased from 0.9 in 1800 to 1.00 in 2150. As indicated in

Figure 4, the reinforcing feedback loop R1 was formed by the stock “democratic states,” the flow “states transitioning to democracy,” and the converters “contacts per year” and “engaging contacts between democratic states and non-democratic states.” The balancing feedback loop B1 was formed by the stock “non-democratic states,” the flow “states transitioning to democracy,” and the converters “not engaged non-democratic states” and “engaging contacts between democratic states and non-democratic states.” As portrayed in

Figure 6, R1 was briefly dominant from 1800 to 1880 and the balancing feedback loop B1 was dominant from 1880. From 1800 to 2150, the total dominance for R1 was 14.0% and for B1 was 86.0%. In t = 2150 years, the balancing feedback loop B1 was fully dominant. In the utopic world, society evolves gradually without a radical shift in the prevailing democratic systems or Earth’s life-giving systems. Given the primary dominance of B1 (depicted in

Figure 6), structural continuity is inherent to all utopic world variations. The transition to regenerative democracy is not triggered and the spreading, strengthening, and stability of democratic states are controlled by the snowball effect related to B1.

Scenario S2—the transitioning world: This describes a societal scenario in which there is a significant lack of achievement of essential needs for all and a significant transgression of planetary boundaries. As portrayed in

Figure 5a, GPI associated with the stock “non-democratic states” decreased from 0.91 in 1800 to zero in 2100. GPI associated with the stock “democratic states” increased from 0.09 in 1800 to 0.90 in 1980 and decreased to zero in 2400. GPI associated with the stock “regenerative democratic states” took off around 2020 and increased to 100.0% in 2400. As portrayed in

Figure 6, similar to the results for S1, in this scenario R1 was dominant from 1800 to 1880. Contrasting the results for S1, B1 was briefly dominant from 1881 to 1960. As indicated in

Figure 4, the reinforcing feedback loop R2 was formed by the stock “regenerative democratic states” and the flow “states transitioning to regenerative democracy.” The balancing feedback loop B2 was formed by the stock “democratic states’, the flow ‘states transitioning to regenerative democracy’, and the converters “not engaged democratic states” and “socio-ecological challenges.” As portrayed in

Figure 6, R2 was dominant from 2012 to 2091 and B2 was dominant from 2096 to 2400. From 1800 to 2400, the total dominance for R1 was 12.3%, for B1 was 20.0%, for R2 was 20.3%, and for B2 was 47.4%. In t = 2400 years, the balancing feedback loop B2 was fully dominant. In the transitioning world, new mindsets are needed to shape societal change and global stewardship towards Degenerative Democracy. Mindset shifts underpin corresponding shifts in societal systems. Intergenerational justice and solidarity are applied to the level of the species, quality of life to the level of the individual, and ecology to the level of Earth’s life-giving systems. Given the variety and dynamics of feedback loops (depicted in

Figure 6), structural change is inherent to all transitioning world variations. The transition to Regenerative Democracy is triggered by socio-ecological challenges and only achieved through the decline of non-democratic states, proactive political participation, and consistent regenerative change of democratic systems.

Scenario S3—the perilous world: This describes a societal scenario in which 99.0% of the world is occupied by non-democratic states and there is a significant lack of achievement of essential needs for all and a significant transgression of planetary boundaries. As portrayed in

Figure 5b, the stock “non-democratic states” slightly decreased from 99.0% to 96.0% in 120 years whereas the stock “regenerative democratic states” slightly increased from 1.0% to 4.0% in 220 years. As portrayed in

Figure 6, R1 was dominant from 0 to 39 years, B2 was dominant from 40 to 199 years, R2 was dominant from 200 years and beyond, and B1 had no significant dominance. From 0 to 600 years, the total dominance for B2 was 68.1%, for R1 was 29.3%, and for R2 was 2.6%. In t = 600 years, B2 = 75.0% was primarily dominant, followed by R1 = 25.0%. In the perilous world, centralized political power, censorship, declined civil liberties, highly pervasive inequality, ecological degradation, and macro-crisis of climate change swamp the transformative mechanisms of democracy. Nourished by the constancy provided by B2, the perilous world is the evil counterpart of the utopic world. Although the initial driving forces are the same for all scenarios, in S3 the momentum towards Regenerative Democracy collapses. In this regard, a societal apartheid emerges and dichotomous spheres of the haves and have-nots and included and excluded are legitimated by non-democratic ideologies and institutional systems. The political, social, and cultural diversity crumbles and an imaginative and epistemological crisis unfolds. Despite significant socio-ecological challenges, the direct transition from non-democratic states to regenerative democracy is unfeasible.

To transition to Regenerative Democracy, it is crucial to rethink and redesign the concept of society not as a compartmentalized realm of individuals within the boundaries of a single nation-state but as a globalized commonwealth of citizens in a hyperconnected world [

5,

46]. Regenerative Democracy only occurs when individuals feel supported by strong relationships that further their capabilities, including a sense of possibility, learning faculties, empowerment, and fulfillment. The more diverse the relationships in social-ecological systems’ networks, the greater the collaboration towards new ways of seeing, listening, thinking, communicating, acting, and caring [

6,

47,

48]. It is very much feasible to envisage individuals collaborating and using their political rights to accomplish Regenerative Democracy through an organization and decision-making process that involves the co-participation of not only humans but also Earth’s life-giving systems. No part of human society is disconnected from Earth’s life-giving systems. Social-ecological co-participation is located at the heart of Regenerative Democracy.

It is critical to consider equality at multiple scales, including the diversity of non-human species with whom all humans share the same planet. To do so, it is necessary to recognize that Earth’s life-giving systems have rights and political voices of their own. Giving voice to nature must also occur through a variety of other forms of human agency in order to meet the needs of those who have experienced the most adverse effects of non-regenerative exploitation. Thus, Regenerative Democracy must transcend the current territorial definition of citizenship and empower individuals to speak for nature and for the future of human society and the planet as a whole. A remarkable case is that of indigenous people, whose close contact with nature makes them better able to listen to the voice of—and connect to—Earth’s life-giving systems, but commonly experience deep marginalization and even genocide [

49]. These traditional communities are frequently victims of systemic injustice and their voices are poorly heard or considered.

Regenerative actions are guided by an integral worldview inspired by nature, cooperating with it, participating in its processes, and learning from it. The Regenerative Democracy design involves not only maintaining the integrity of Earth’s life-giving systems and safeguarding their diversity, but also nurturing and strengthening their systemic health and complexity. It also fosters human learning on the leverage patterns of natural systems, offering human societies the possibility of designing economic systems in synergy with nature, instead of the destructive ones that have been created to a large extent by modern societies.

The ongoing transformations of societal systems towards higher degrees of complexity reveal that prosperity can be compatible with a system thinking design modeled off of nature. Life creates conditions conducive to life, acting through a process of diversification and subsequent reintegration of diversity at higher levels of complexity and new forms of collaboration [

50,

51]. Regenerative Democracy applies life’s operating instructions and socio-ecological literacy to co-create a political future where human society and all of life can flourish. It is crucial to envisage and create socio-ecological systems that sustain one another in a design in which human actions become healing forces to Earth’s life-giving systems, fostering equality and resilience, empowering individuals, and revitalizing ecosystems and communities.

The conventional wisdom is that economies must grow whether or not they make all people flourish. The current GDP per capita (in current USD) is about 25 times higher than its value in 1960 [

33]. Although economic growth brought prosperity to billions of people, it has also become incredibly divisive, with the vast share of returns to wealth accruing to the top 1.0% [

35]. Furthermore, current democratic states, including highly affluent and liberal ones, are largely failing to ensure equality and safeguard Earth’s life-giving systems. Millions of people worldwide still fall short on their most essential needs while at least four critical planetary boundaries have been already transgressed [

3,

4,

5]. Achieving Regenerative Democracy requires reimagining and redesigning the ever-rising line of global economic growth, decoupling it from increasing inequality and non-regenerative exploitation of natural resources.

Nothing in nature grows forever. It is time to redesign the polity in order to meet the needs for all within the means of Earth, making societies flourish whether or not their economies grow. It is urgent to create economic systems that are regenerative and distributive by intention and design, working with and within the cycles of the living world, so that resources are never depleted and so that wealth, knowledge, social empowerment, and political voice are distributed to many. Regenerative Democracy enables societies to overcome the structural dependency on material growth, unleashing the potential for all people to flourish with boundless innovation, socio-ecological co-participation, a sense of belonging, and meaning.