The creative motivation in the organization, environmental factors, and external motivation of the organization also affect the creative behavior of employees [

42]. These organizational environment factors guide, promote, adjust, bridge, or influence followers’ effective following behavior and creative work behavior. Many researchers have analyzed the role of perceived organizational support and sustainable leadership in employee work behavior.

2.4.1. The Moderating Role of Perceived Organizational Support

Wilson and colleagues observed that different followers obtain different degrees of support in the organization, and thus organizational support plays a certain role in the process of transforming followers’ effective following behavior into creative work behavior [

50]. Researchers proposed that organizational support has an impact on employee work behavior, and particularly on employees’ innovative behavior and that the size of the impact is related to the employees’ perceived organizational support [

51].

After Eisenberger, different scholars regarded perceived organizational support as an independent variable and concluded that perceived organizational support had a positive correlation with employee job performance [

52]. Although these studies basically design perceived organizational support as an independent variable, the results show that perceived organizational support did affect the followers’ work behavior.

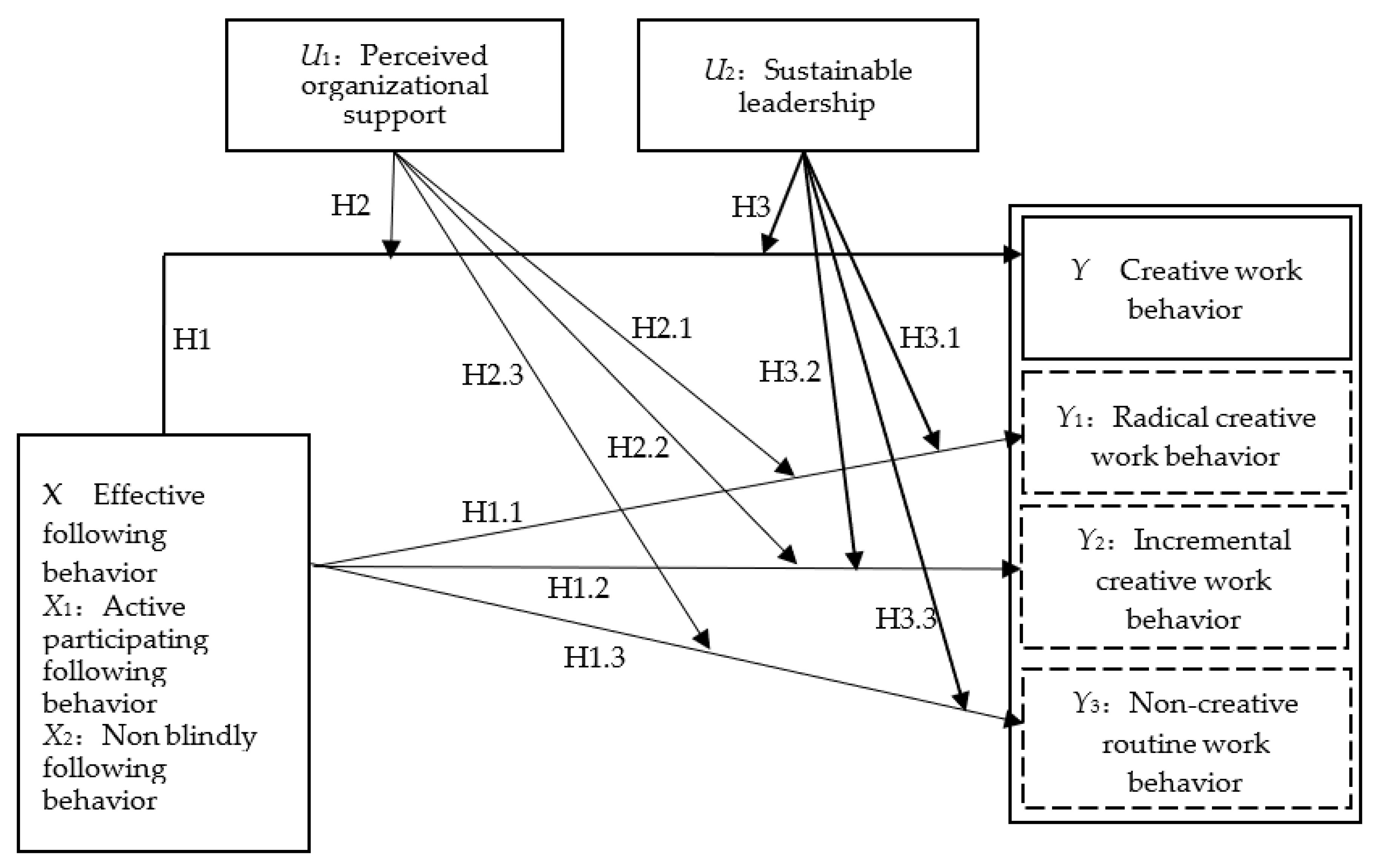

When effective following behavior is regarded as the antecedent variable of work behavior, perceived organizational support will strengthen or weaken the influence of effective following behavior on work performance. In other words, if effective following behavior is considered, perceived organizational support can enhance or weaken an antecedent between employee effective following behavior and creative work behavior; that is, perceived organizational support is the moderator of the relationship between the two variables. Thus, we have the following hypothesis:

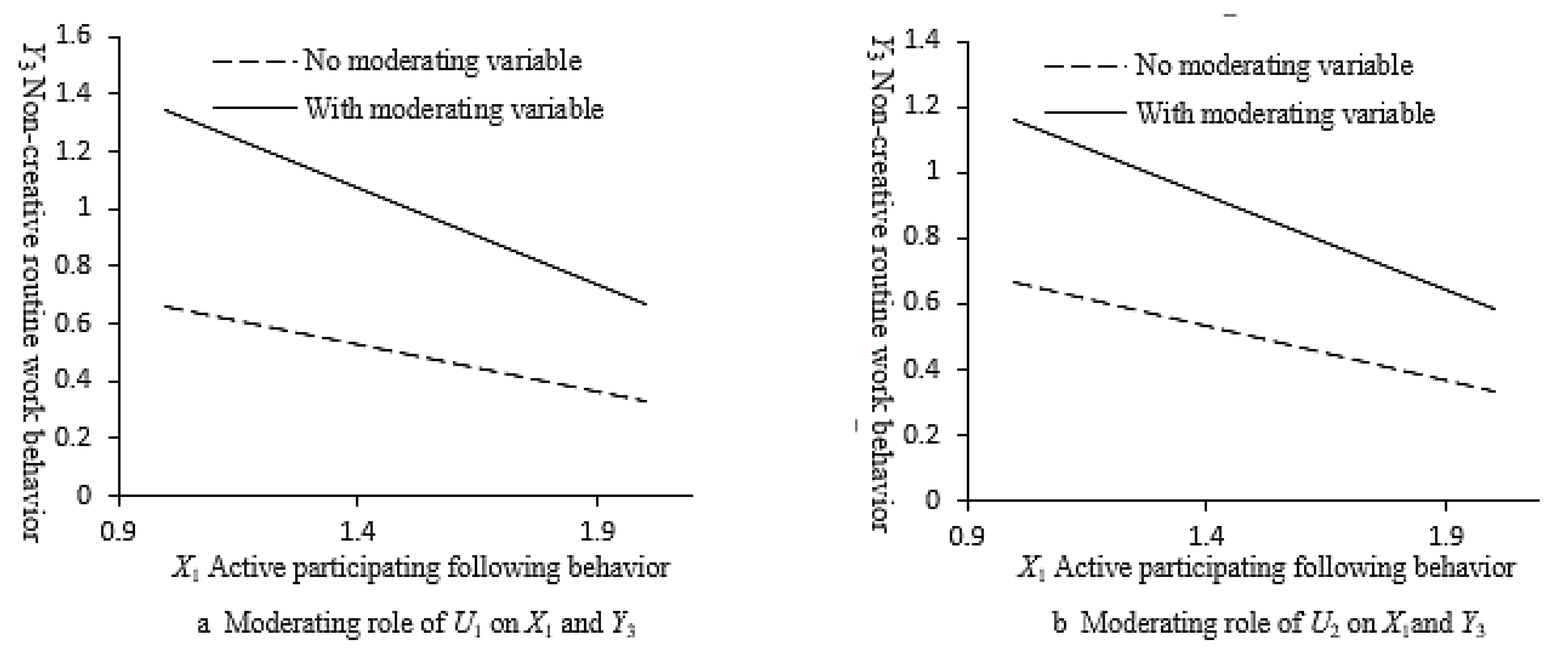

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Followers’ perceived organizational support (U1) moderates the relationship between effective following behavior (X) and derived work behavior (Y).

The work behavior derived from followers’ effective following behavior can be divided into three dimensions. Followers’ perceived organizational support has different moderating effects on the relationship between the two dimensions of effective following behavior and the three dimensions of derived work behavior.

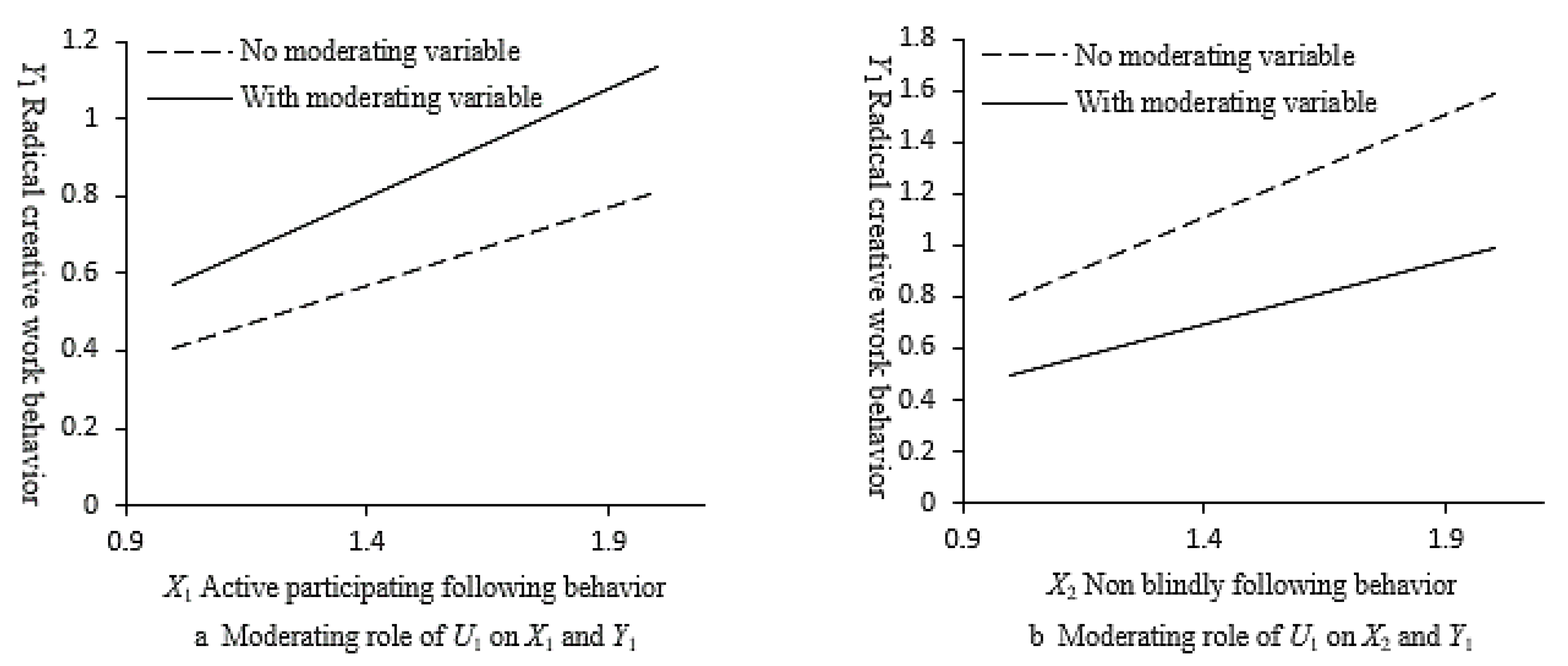

In terms of the relationship between perceived organizational support and followers’ radical creative work behavior, organizational support itself can promote followers’ radical creative work behavior [

53]. That is, an interaction between perceived organizational support and followers’ active participating following behavior. When followers feel organizational support, they are more willing to turn active participating following behavior into radical creative work behavior [

54].

However, in a certain sense, perceived organizational support will produce the pressure of obedience on followers, which has a certain restrictive effect on followers’ non-blind following behavior; this effect is negative to a certain extent because non-blind following behavior tends to work independently and autonomously [

54]. Through the above analysis, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2.1 (H2.1). Followers’ perceived organizational support (U1) has a positive moderating effect on the relationship between active participating following behavior (X1) and radical creative work behavior (Y1) and a negative moderating effect on the relationship between non-blind following behavior (X2) and radical creative work behavior (Y1).

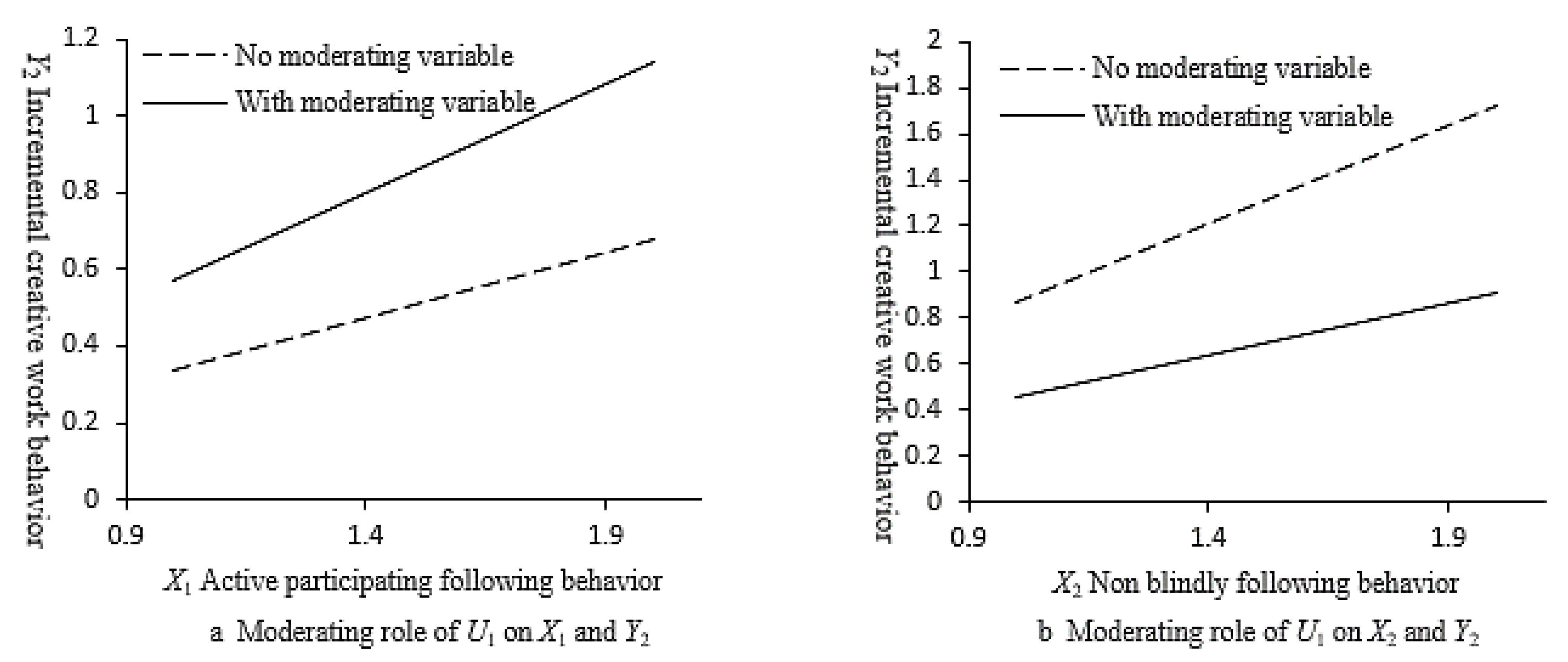

Followers’ incremental creative work behavior is a progressive creative behavior. When they feel organizational support, they will also strengthen this type of creative behavior [

55]. There is an interaction between perceived organizational support and active participating following behavior, and when followers feel organizational support, they are more willing to turn active participating following behavior into incremental creative work behavior; therefore, the interaction has a strengthening effect on incremental creative work behavior [

54].

In addition, in a certain sense, perceived organizational support will produce the pressure of obedience on followers, which will also have a certain restrictive effect on followers’ non-blind following behavior; this effect is negative to a certain extent because non-blind following behavior leads to intentions to work independently and autonomously [

56]. Through the above analysis, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2.2 (H2.2). Followers’ perceived organizational support (U1) has a positive moderating effect on the relationship between active participating following behavior (X1) and incremental creative work behavior (Y2) and a negative moderating effect on the relationship between non-blind following behavior (X2) and incremental creative work behavior (Y2).

The non-creative routine work behavior of followers is a type of behavior under the contract, and when followers face some tasks or work, they prefer to finish the work in the form of quantity. Such followers regard organizational support as part of their reward, welfare, or rights, they are passive in their work, and their participation is simply to complete the task. Their perceived organizational support is not strong [

57], and they often regard organizational support as necessary. Followers with high perceived organizational support and with high participatory following behavior were found to be more reluctant to adopt non-creative routine work behavior [

54].

Vice versa, followers with low participatory following behavior often cannot perceive organizational support and are more willing to adopt non-creative routine work behavior [

58]. In other words, perceived organizational support can strengthen the relationship between participatory following behavior and non-creative routine work behavior [

58]. Then, non-blind following behavior is the characteristic of such followers who work with quantity. As they always have a sense of being at the edge of the organization, perceived organizational support has no moderating effect on the relationship between non-blind following behavior and non-creative routine work behavior. Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2.3 (H2.3). Followers’ perceived organizational support (U1) has a negative reinforcement effect on the relationship between active participating following behavior (X1) and non-creative routine work behavior (Y3) and no significant moderating effect on the relationship between non-blind following behavior (X2) and non-creative routine work behavior (Y3).

2.4.2. The Moderating Role of Sustainable Leadership

Fischer and co-workers studied the components of individual creativity in an organization; they found that the individual creativity in the organization promoted the innovation of the organization, the organizational innovation environment or atmosphere improved the individual creativity, and the organizational atmosphere included sustainable leadership [

42].

The connotation of sustainable leadership mainly emphasizes that leaders’ sustainable inclusion of others is reflected in their behaviors, such as inviting followers to participate in decision-making discussions and decision-making implementation [

34], recognizing other people’s views and paying attention to other people’s opinions or suggestions according to the sustainable environment. Later, Nembhard and Edmondson (2006) conducted a quantitative study on this concept [

59], while Carmeli et al. (2010) extracted three dimensions of sustainable leadership: openness, accessibility, and availability according to the sustainable environment [

60].

As far as followers’ creative behavior is concerned, creation means not sticking to conventions, and failure is often its companion. When theoretically analyzed the success and failure of innovation, it pointed out that failure is that the work did not achieve the expected goal [

61].

It can be seen that whether it is innovative or creative behavior, the result has the risk of failure, and the sustainable leader’s response to the followers’ success or failure will inevitably affect the followers’ work behavior, and the leader’s tolerance to failure affects the followers’ decision-making of what type of work behavior to adopt. Sustainable leadership is a type of relationship between leaders and followers (or subordinates), which emphasizes the interaction and interdependence between sustainable leaders and followers, and emphasizes the tolerance, encouragement, and inclusion of sustainable leaders to followers and the environment.

In an organization, when followers perceive the sustainable characteristics of their leaders, they will adjust their work behavior. This adjustment is associated with and interacts with their participatory following behavior to strengthen or weaken their work behavior in a sustainability perspective. Non-blind following behavior may be an independent following behavior in a certain sense; therefore, perceived sustainable leadership does not necessarily positively strengthen the relationship between non-blind following behavior and work behavior.

Through the above analysis of the role of sustainable leadership and the psychological process of followers’ work behavior, we propose the following hypothesis:

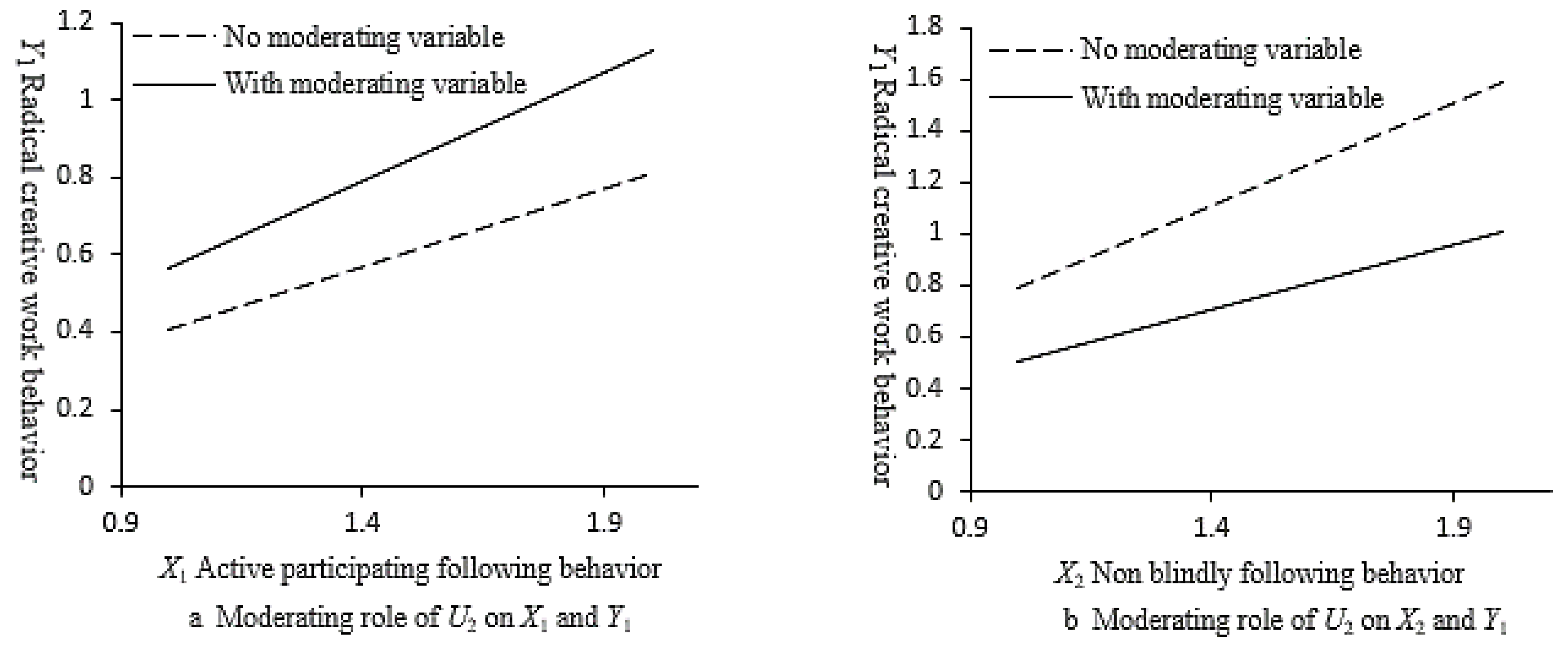

Hypothesis 3 (H3). Followers’ perceived sustainable leadership (U2) moderates the relationship between effective following behavior (X) and derived work behavior (Y).

In a certain sense, followers’ creative work behavior has an uncertainty of work results. When followers perceive leader sustainability, the pressure caused by the possible adverse effects of work uncertainty will be reduced, and thus they are more willing to adopt radical creative behavior in their work [

62]. When a follower perceives the existence of sustainable leadership, this strengthens his behavior of participating in organizational work and doing a good job, which is more conducive to creative work [

61]. At the same time, followers with high non-blind following behavior seldom perceive leader sustainability and often turn a blind eye to leadership behavior, which inhibits their creative work. In this way, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 3.1 (H3.1). Followers’ perceived sustainable leadership (U2) has a positive moderating effect on the relationship between active participating following behavior (X1) and radical creative work behavior (Y1) and a negative moderating effect on the relationship between non-blind following behavior (X2) and radical creative work behavior (Y1).

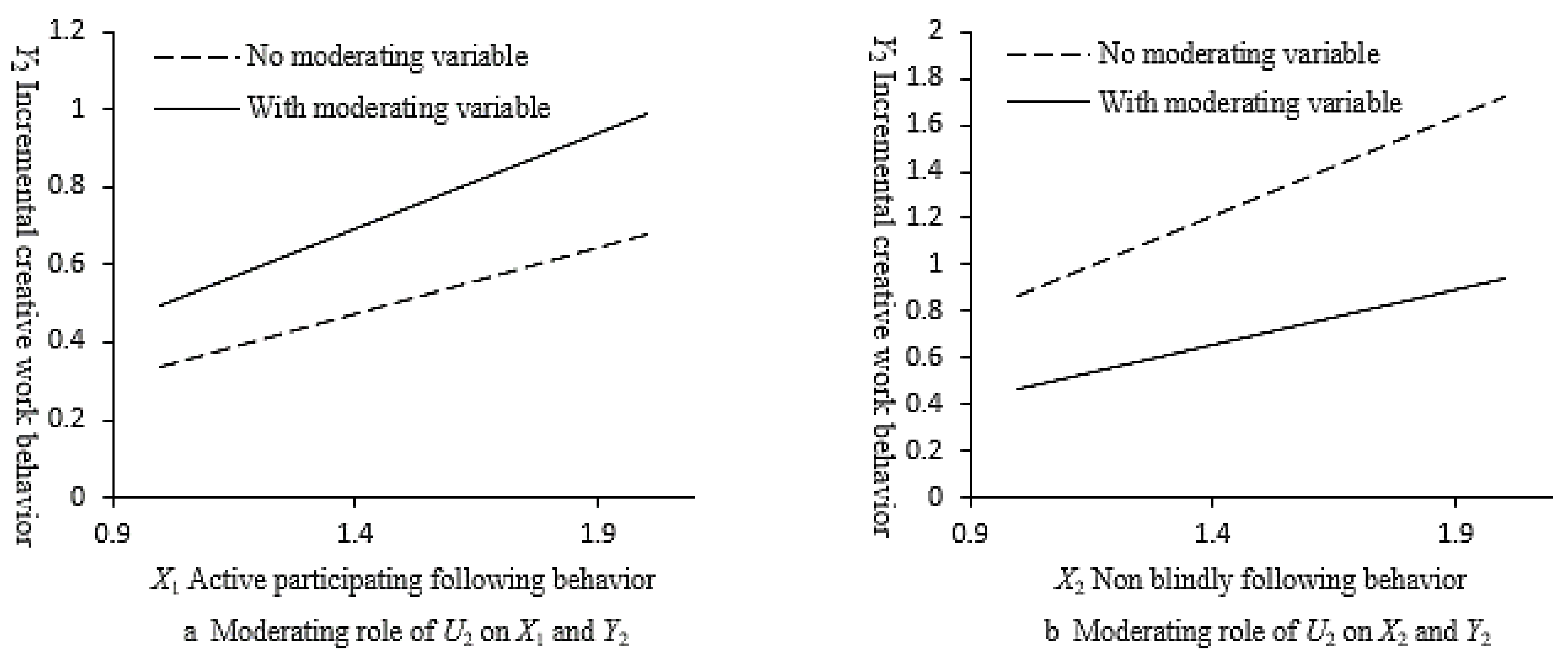

Compared with radical creative work behavior, incremental creative work behavior is a type of progressive creative behavior, and its results are less uncertain; however, there is still some uncertainty [

63]. Therefore, when followers perceive sustainable leadership, the pressure caused by the possible adverse effects of such small uncertainty in the work will be reduced, and they are more willing to adopt incremental creative behavior in their work [

64].

When a follower perceives the existence of sustainable leadership, this strengthens their behavior of participating in organizational work and doing a good job, which is more conducive to creative work, and, in general, followers are more willing to adopt incremental creative work behavior [

61]. In addition, followers with high non-blind following behavior seldom perceive leader sustainability and ignore leadership behavior, which also inhibits their incremental creative work [

62]. Compared with radical creative work, this inhibition is stronger. The following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 3.2 (H3.2). Followers’ perceived sustainable leadership (U2) has a positive moderating effect on the relationship between active participating following behavior (X1) and incremental creative work behavior (Y2) and a negative moderating effect on the relationship between non-blind following behavior (X2) and incremental creative work behavior (Y2).

In the organization, the non-creative routine work behavior of followers is a type of behavior under the contract. These followers’ perception of sustainable leadership is not strong, and when they face tasks or work, they prefer to complete the work in the form of the environment [

65]. When followers perceive the leadership as sustainable and their participatory following behavior is high, they are more reluctant to adopt non-creative routine work behavior and more willing to adopt creative work behavior [

66].

Vice versa, followers with low participatory following behavior often cannot perceive the existence of inclusive leadership and are more willing to adopt non-creative routine work behavior [

65]. In other words, perceived inclusive leadership can strengthen the relationship between participatory following behavior and non-creative routine work behavior. On the other hand, non-blind following behavior is the characteristic of such followers who work with quantity, and they always have the feeling of keeping a distance from the leader; therefore, sustainable leadership has no moderating effect on the relationship between non-blind following behavior and non-creative routine work behavior [

67]. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3.3 (H3.3). Follower sustainable leadership (U2) has a negative reinforcement effect on the relationship between active participating following behavior (X1) and non-creative routine work behavior (Y3) and no significant moderating effect on the relationship between non-blind following behavior (X2) and non-creative routine work behavior (Y3).