The Evaluation Framework in the New CAP 2023–2027: A Reflection in the Light of Lessons Learned from Rural Development

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Information Sources and Materials

- several information sources and magazines were explored;

- interpretations are presented in a clear way;

- assertions are logically supported.

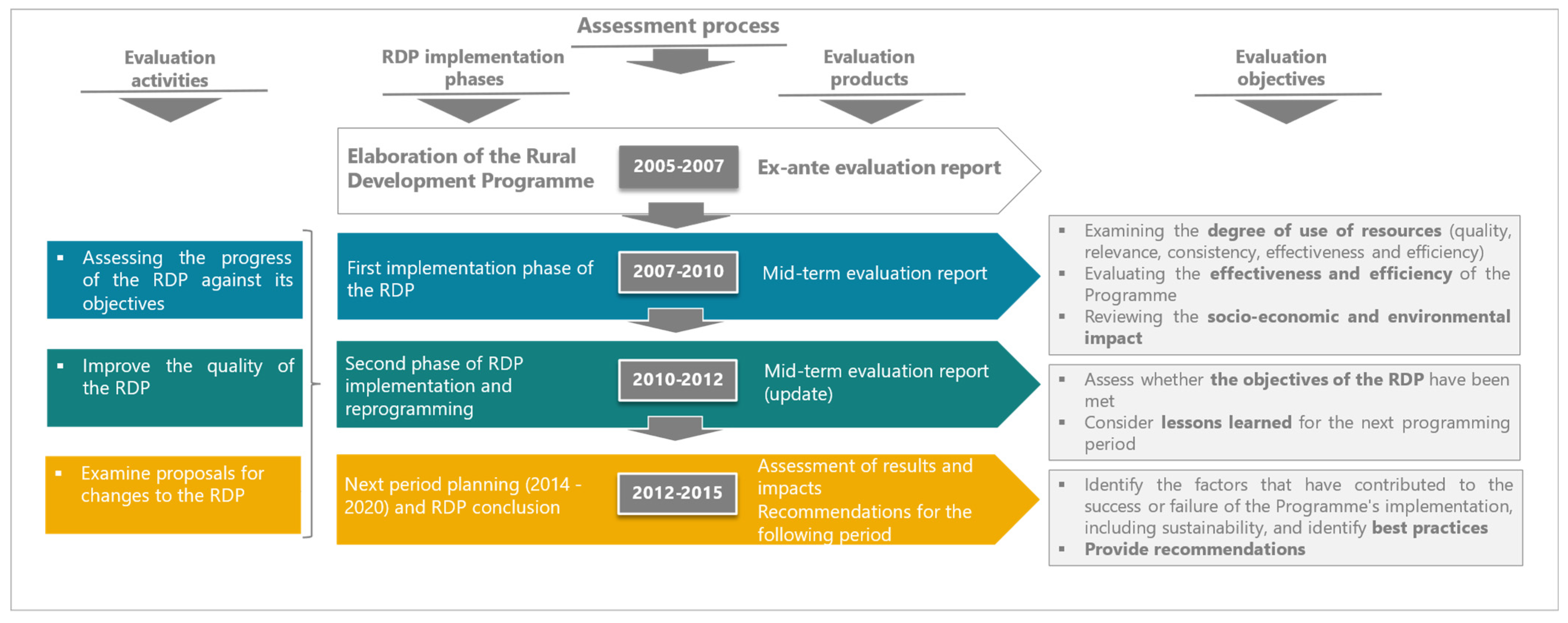

3. The Evolution in the Assessment of Rural Development

4. The Innovations Adopted for the Evaluation in 2014–2020 Programming Period

- the proposition of the new CMES for the rural development as part of the CMEF;

- the focus of the evaluation process via EP;

- the inclusion of evaluation results in Chapter 7 of the “enhanced” Annual Implementation Reports (AIR).

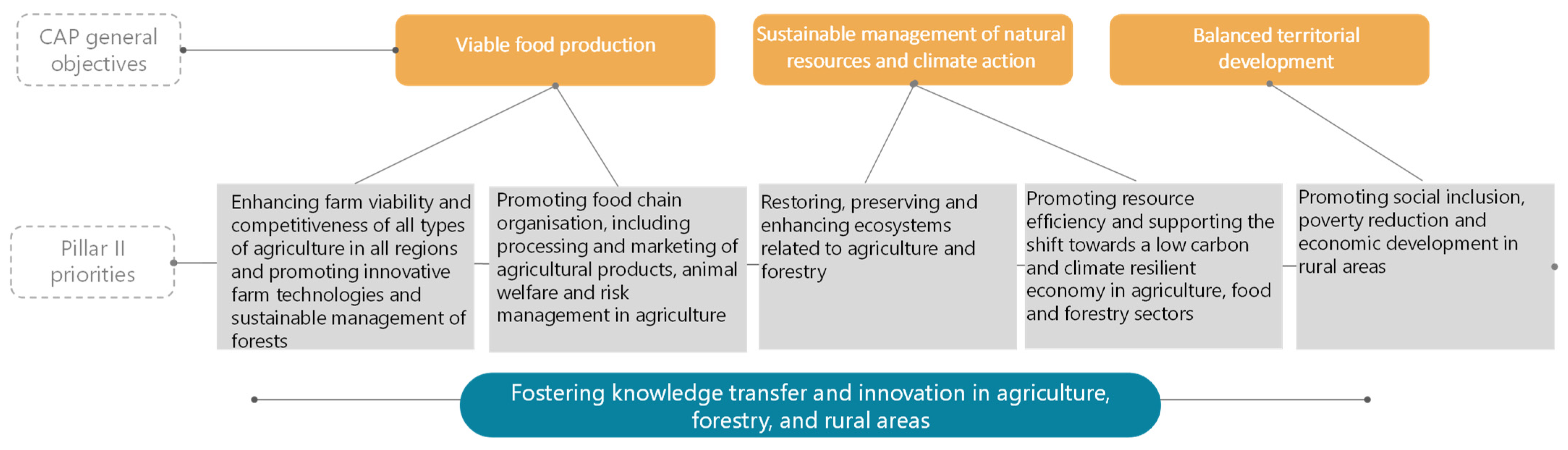

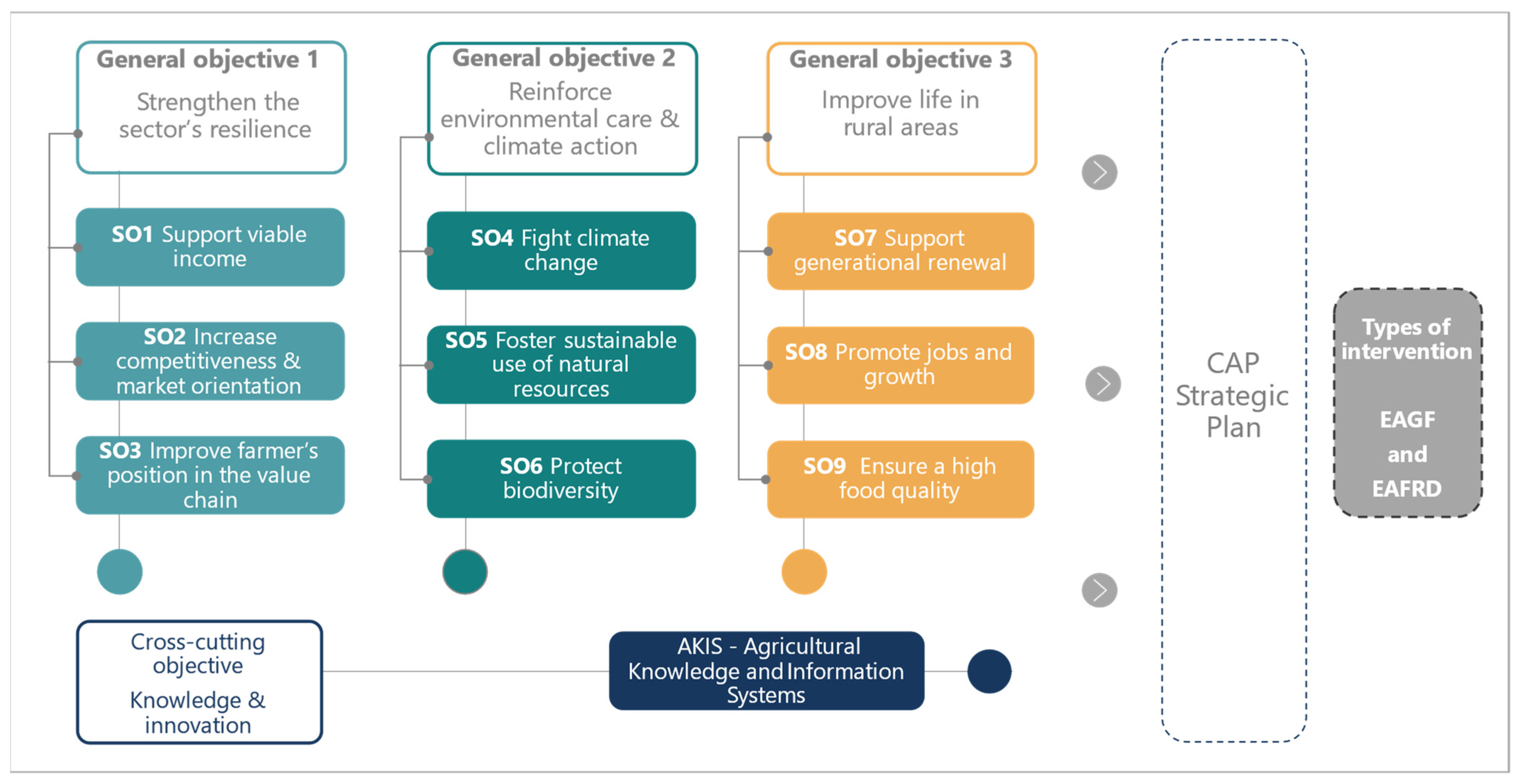

5. Post-2020: The State of Play

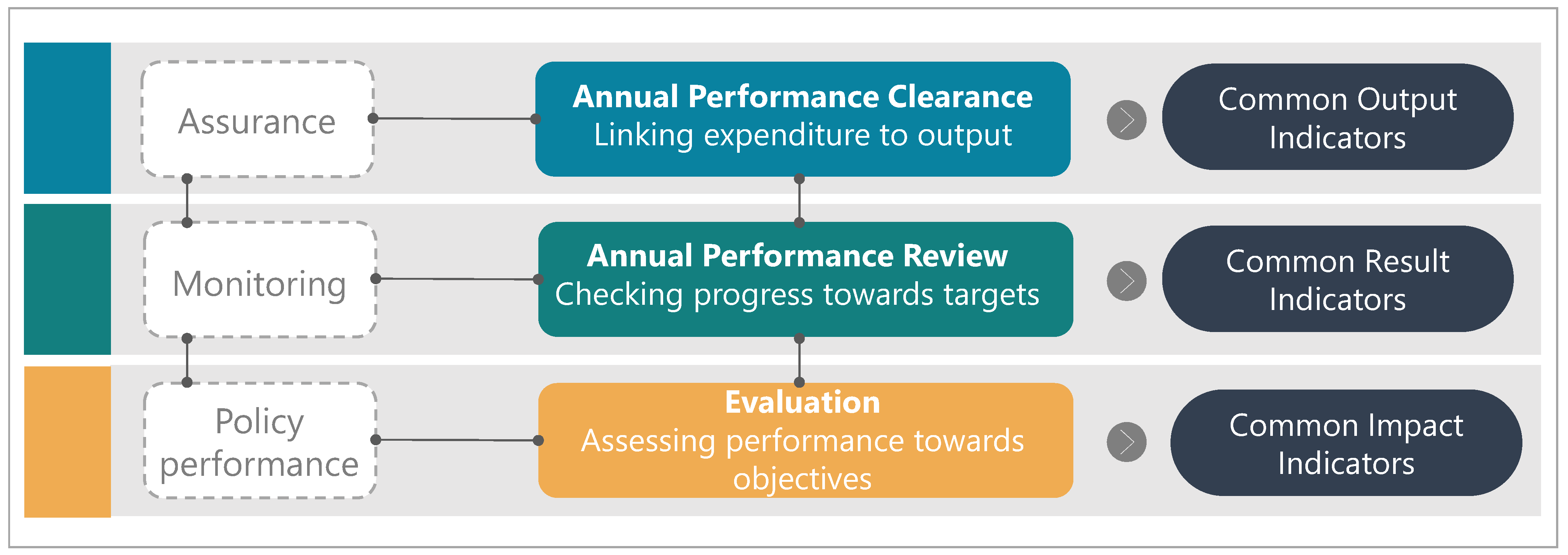

- context indicators remain pertinent in the intervention logic set up and follow up;

- common output indicators will annually link expenditure with the performance implementation (performance clearance);

- a set of result indicators will be used to reflect whether the supported interventions contribute to achieving the EU specific objectives;

- annual performance follow-up will rely on a limited, but more targeted, list of common result indicators (performance review). It is currently supposed the use of only one indicator for each EU specific objective;

- multiannual assessment of the overall policy is proposed based on common impact indicators (evaluation).

6. Final Remarks and Two Questions for the Future

6.1. To Be Performing or Not to Be Performing?

6.2. Sound Evidence and Learning, but for Whom?

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AIR | Annual Implementation Report |

| CAP | Common Agricultural Policy |

| CMEF | Common Monitoring and Evaluation Framework |

| CMES | Common Monitoring and Evaluation System |

| EC | European Commission |

| EP | Evaluation Plan |

| EU | European Union |

| LEADER | Liaison entre actions de développement de l’économie rurale |

| MA | Managing Authority |

| MS | Member State |

| NDM | New Delivery Model |

| NRN | National Rural Network |

| NSP | National Strategic Plan |

| PF | Performance Framework |

| RD | European Rural Development |

| RDP | Rural Development Programme |

| SF | Structural Funds |

References

- Esposti, R.; Sotte, F. Sviluppo Rurale e Occupazione (Rural Development and Employment); Franco Angeli Editore: Milan, Italy, 1999; pp. 1–294. ISBN 8846419243. [Google Scholar]

- van der Ploeg, J.D.; Long, A.; Banks, J. Living Countrysides. Rural Development the State of the Art, in Living Countryside, Rural Development Processes in Europe: The State of the Art; Elsevier: Doetinchem, The Netherlands, 2002; pp. 1–231. ISBN 9789054391173. [Google Scholar]

- Sotte, F. Sviluppo rurale e implicazioni di politica settoriale e territoriale. Un approccio evoluzionistico (Rural development and sectoral and territorial policy implications. An evolutionary approach). In Politiche, Governance e Innovazione per le Aree Rurali; Cavazzani, A., Gaudio, G., Sivini, S., Eds.; Edizioni Scientifiche Italiane: Naples, Italy, 2006; pp. 61–80. ISBN 8849511299. [Google Scholar]

- Mantino, F. Lo Sviluppo Rurale in Europa. Politiche, Istituzioni e Attori Locali dagli Anni ‘70 ad Oggi (Rural Development in Europe. Policies, Institutions and Local Actors from the 1970s to Today); Edagricole–New Business Media: Milan, Italy, 2008; pp. 1–312. ISBN 9788850652549. [Google Scholar]

- Leonardi, I.; Sassi, M. Il Modello di Sviluppo Rurale Definito dall’UE dalla Teoria all’Attuazione: Una Sfida Ancora Aperta (The EU Rural Development Model from Theory to Implementation: Still an Open Challenge). Quaderno di Ricerca n. 6.; Copyland: Pavia, Italy, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Pulina, P. La valutazione delle politiche per lo sviluppo rurale nella prospettiva post 2020 (Evaluating rural development policies in the post-2020 perspective). Agriregionieuropa 2018, 52. Available online: https://agriregionieuropa.univpm.it/it/content/article/31/52/la-valutazione-delle-politiche-lo-sviluppo-rurale-nella-prospettiva-post-2020 (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- European Commission. The Future of Food and Farming–For a Flexible, Fair and Sustainable Common Agricultural Policy; EU Publications Office: Luxembourg, Luxembourg, 2007; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_17_4841 (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- Cristiano, S. Il Futuro dei Sistemi di Monitoraggio e Valutazione Delle Politiche di Sviluppo Rurale: Alcune Riflessioni (The Future of Monitoring and Evaluation Systems for Rural Development Policies: Some Reflections), 2011, Italian Network for Rural Development 2007–2013, Rome, Ministry of Agricultural, Agri-Food and Forestry Policies, 6–16. Available online: https://www.reterurale.it/flex/cm/pages/ServeAttachment.php/L/IT/D/a%252F0%252Fe%252FD.8b06e6fc32d8c1b9a3f9/P/BLOB%3AID%3D5703/E/pdf (accessed on 11 November 2020).

- Cagliero, R.; Cristiano, S. Valutare i programmi di sviluppo rurale: Approcci, metodi ed Esperienze; (Evaluating Rural Development Programs: Approaches, Methods And Experiences); INEA: Rome, Italy, 2013; pp. 6–111. ISBN 978-88-8145-2910. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, J.; Clark, M.; Kirwan, J.; Kambites, C.; Lewis, N.; Molnarova, A.; Thompson, K.; Mantino, F.; Tarangioli, S.; Monteleone, A.; et al. Review of Rural Development Instrument: DG Agri Project 2006-G4–10. Final Report; University of Gloucestershire: Cheltenham, UK, 2008; pp. 1–178. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/food-farming-fisheries/key_policies/documents/ext-study-rurdev-full_report_2008_en.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2021).

- Lucatelli, S.; Monteleone, A. Valutazione e Sviluppo delle Aree Rurali: Un Approccio Integrato Nella Valutazione delle Politiche di Sviluppo (Evaluation and Development of Rural Areas: An Integrated Approach to the Evaluation of Development Policies); Public Investment Evaluation Unit (UVAL), Ministry of Economy and Finance–Department of Development Policy: Rome, Italy, 2005; pp. 1–190. Available online: https://www.mise.gov.it/images/stories/recuperi/Sviluppo_Coesione/9.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2020).

- Mantino, F.; Monteleone, A.; Pesce, A. Monitorare e Valutare i Fondi Strutturali 2000–2006 (Monitoring and Evaluating the Structural Funds 2000–2006); INEA: Rome, Italy, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Monteleone, A. La Riforma dello Sviluppo Rurale: Novità e Opportunità, Strumenti per la Programmazione 2007–2013 (The Rural Development Reform: New Features and Opportunities, Tools for 2007–2013 Programming). Quaderno n.1; INEA: Rome, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Naldini, A. Improvements and risks of the proposed evaluation of Cohesion Policy in the 2021–27 period: A personal reflection to open a debate. Evaluation 2018, 24, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrin, J.; Colnot, L. Research for REGI Committee–The Role of Evaluation in Cohesion Policy, European Parliament, Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies, Brussels, Brussels. 2020. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2020/629219/IPOL_STU(2020)629219_EN.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2021).

- Smismans, S. Policy evaluation in the EU: The challenges of linking ex ante and ex post appraisal. Eur. J. Risk Regul. 2015, 6, 6–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, A. Come rendere la valutazione delle politiche meglio utilizzabile nel processo decisionale pubblico? (How to make policy evaluation more usable in public decision-making?). In Proceedings of the Seventh National Conference of Statistics, Rome, Italy, 9–10 November 2004; Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/files/2011/02/Atti.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- Patton, M.Q. Utilization-Focused Evaluation: The New Century Text, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1997; ISBN 978–0803952645. [Google Scholar]

- Bandstein, S.; Hedblom, E. IFAD’s Management Response System–The Agreement at Completion Point Process; SADEV: Karlstad, Sweden, 2008; ISBN 978-91-85679-11-9. Available online: https://www.saved.se (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- Senge, P. The Fifth Discipline. The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization; Random House: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Argyris, C.; Schön, D.A. Organizational Learning II: Theory, Method, and Practice; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, C.H. Have we learned anything new about the use evaluation? Am. J. Eval. 1998, 19, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, P.H.; Lipsey, M.W.; Freeman, H.E. Evaluation: A Systematic Approach, 6th ed.; Sage Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1999; ISBN 9780761908937. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Discovering process use. Evaluation 1998, 4, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramdhani, A.; Ramdhani, M.A.; Amin, A.S. Writing a literature review research paper: A step-by-step approach. Int. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2014, 3, 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Nakano, D.; Muniz, J., Jr. Writing the literature review for an empirical paper. Production 2018, 28, e20170086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popay, J.; Roberts, H.; Sowden, A.; Petticrew, M.; Arai, L.; Britten, N.; Rodgers, M.; Roen, K.; Duffy, S. Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews: Final Report; ESRC Methods Programme: Swindon, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Denyer, D.; Tranfield, D. Producing a systematic review. In The Sage Handbook of Organizational Research Methods; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2009; pp. 671–689. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh, T. Meta-narrative mapping: A new approach to the systematic review of complex evidence. In Narrative Research in Health and Illness; Hurwitz, B., Greenhalgh, T., Skultans, V., Eds.; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Agra CEAS Consulting. Synthesis of Rural Development Mid-Term Evaluation 2005. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/food-farming-fisheries/key-policies/common-agricultural-policy/cmef/rural-areas/synthesis-rural-development-mid-term-evaluations_en (accessed on 30 April 2021).

- Countryside and Community Research Institute. Assessing the Impact of Rural Development Policy (incl. LEADER) 2010. Deliverable D3.2. Available online: http://dspace.crea.gov.it/handle/inea/734 (accessed on 30 April 2021).

- Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development (European Commission). Ex-Post Evaluation of Rural Development Programmes 2000–2006; Publications Office of the EU: Luxembourg, Luxembourg, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development (European Commission). Synthesis of Mid-Term Evaluations of Rural Development Programmes 2007–2013; Publications Office of the EU: Luxembourg, Luxembourg, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development (European Commission). Synthesis of Rural Development Programmes (RDP) Ex-Post Evaluations of Period 2007–2013; Publications Office of the EU: Luxembourg City, Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, J.; Bradley, D.; Hill, B. Towards an enhanced evaluation of European rural development policy reflections on United Kingdom experience. Économie Rural. 2008, 307, 53–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission of the European Communities. Evaluating Socio-Economic Programmes; Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxembourg City, Luxembourg, 1999; Volumes 1–6 MEANS Collection. [Google Scholar]

- Commission of the European Communities. A Framework for Indicators for the Economic and Social Dimensions of Sustainable Agriculture and Rural Development; Agriculture Directorate-General: Brussels, Belgium, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Monteleone, A. Quale il futuro della politica di sviluppo rurale? (What is the future of rural development policy?). Pagri/IAP Politica Agric. Internazionale 2006, 1, 63–81. [Google Scholar]

- Mantino, F. The Reform of EU Rural Development Policy and the Challenges Ahead. Notre Eur. Policy Pap. 2010, 40. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/49294/ (accessed on 25 October 2020).

- Dax, T.; Oedl-Wieser, T.; Strahl-Naderer, W. Altering the evaluation design for rural policies. Eur. Struct. Investig. Funds J. 2014, 2, 141–152. [Google Scholar]

- Bergschmidt, A. Powerless evaluation. Eurochoices 2009, 8, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maye, D.; Enticott, G.; Naylor, R. Theories of change in rural policy evaluation. Sociol. Rural. 2020, 60, 198–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development (European Commission). Investment Support under Rural Development Policy. Final Report; Publications Office of the EU: Luxembourg City, Luxembourg, 2014; ISBN 978-92-79-35314-7. [Google Scholar]

- Michalek, J. Counterfactual Impact Evaluation of EU Rural Development Programmes—Propensity Score Matching Methodology Applied to Selected EU Member States; Publications Office of the EU: Luxembourg City, Luxembourg, 2012; Volume 1: A Micro-level Approach. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristiano, S.; Licciardo, F. La valutazione on-going dei programmi di sviluppo rurale 2007–2013 (Ongoing evaluation of rural development programmes 2007–2013). Ital. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2017, 2, 173–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolli, M.; Fagiani, P.; Monteleone, A. Sistema Nazionale di Monitoraggio e Valutazione delle Politiche di Sviluppo Rurale. Organizzazione della Valutazione on-Going (National System for Monitoring and Evaluation of Rural Development Policies. Organisation of the on-Going Evaluation). Italian Network for Rural Development 2007–2013; Ministry of Agricultural, Agri-food and Forestry Policies: Rome, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fucilli, V.; De Blasi, G.; Monteleone, A. Le valutazioni dei piani di sviluppo rurale: Uno studio meta valutativo (Evaluations of rural development plans: A meta-evaluation study). Aestimum 2009, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardulli, N.; Tenna, F. L’applicazione delle metodologie proposte dal manuale del Quadro Comune di Monitoraggio e Valutazione (QCMV) alla valutazione dei programmi di sviluppo rurale 2007–2013: Limiti attuali e spunti di riflessione per il futuro (The application of the methodologies proposed by the CMEF to the evaluation of the 2007–2013 Rural Development Programmes: Current limitations and points for reflection for the future). Rass. Ital. Valutazione 2010, 48, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristiano, S.; Fucilli, V.; Monteleone, A. La valutazione della politica di sviluppo rurale (Evaluation of rural development policy). In Il Libro Bianco della Valutazione in Italia; Vergani, A., Ed.; Franco Angeli: Milan, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development. Technical Handbook on the Monitoring and Evaluation Framework of the Common Agricultural Policy 2014–2020. 2015. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/transparency/regexpert/index.cfm?do=groupDetail.groupDetailDoc&id=21095&no=3 (accessed on 30 April 2021).

- Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development (European Commission). The Monitoring and Evaluation Framework for the Common Agricultural Policy 2014–2020. Brussels, Belgium. 2015. Available online: http://publications.europa.eu/resource/genpub/PUB_KF0415328ENN.1.1 (accessed on 14 May 2021).

- OECD. Evaluation of Agricultural Policy Reforms in the European Union: The Common Agricultural Policy 2014–20; OECD Publishing: Paris, Italy, 2017; ISBN 978-92-64-27868-4. [Google Scholar]

- Pollermann, K.; Aubert, F.; Berriet-Solliec, M.; Laidin, C.; Lépicier, D.; Pham, H.V.; Raue, P.; Schnaut, G. LEADER as a European policy for rural development in a multilevel governance framework: A comparison of the implementation in France, Germany and Italy. Eur. Countrys. 2020, 12, 156–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fucilli, V. Mid-term evaluation of rural development plans in Italy: Comparing models. New Medit 2009, 8, 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Vidueira, P.; Rivera, M.; Mesa, B.; Díaz-Puente, J.M. Mid-Term impact estimation on evaluations of rural development programs. Elsevier Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 191, 1596–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagliero, R. I principali indirizzi per la valutazione dei Psr nel periodo 2014–20 (Main guidelines for the evaluation of RDPs in the 2014–2020 period). Agriregionieuropa 2013, 33. Available online: https://agriregionieuropa.univpm.it/it/content/article/31/33/i-principali-indirizzi-la-valutazione-dei-psr-nel-periodo-2014-20 (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- Zahrnt, V. The Limits of (Evaluating) Rural Development Policies. 2010. Available online: http://capreform.eu/the-limits-of-evaluating-rural-development-policies/ (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- Schuh, B.; Beiglböck, S.; Novak, S.; Panwinkler, T.; Tordy, J.; Fischer, M.; Zondag, M.J.; Dwyer, J.; Banski, J.; Saraceno, E. Synthesis of Mid-Term Evaluations of Rural Development Programmes 2007–2013. Final Report; ÖIR GmbH: Wien, Austria, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wimmer, H.; Van Soetendael, M. The mid-term evaluation reports and the CMEF: What can we learn about the monitoring and evaluation system and process? Rural Eval. News 2011, 7, 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development. Establishing and Implementing the Evaluation Plan of 2014–2020 RDPs. Guidelines. 2015. Available online: https://enrd.ec.europa.eu/evaluation/publications/guidelines-establishing-and-implementing-evaluation-plan-2014-2020-rdps_en (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Camaioni, B.; Cagliero, R.; Licciardo, F. Cosa abbiamo appreso dalle RAA potenziate e dal Performance Framework (What we have learned from the enhanced AIRs and the Performance Framework). In I PSR 2014–2020 al Giro di Boa. Rapporto di Monitoraggio Strategico al 31.12.2018; Tarangioli, S., Ed.; Ministry of Agricultural, Agri-food and Forestry Policies: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development. Summary Report. Synthesis of the Evaluation Components of the 2017 Enhanced AIR–Chapter 7. Brussels, Belgium. 2017. Available online: https://enrd.ec.europa.eu/evaluation/publications/summary-report-synthesis-evaluation-components-2017-enhanced-air-chapter-7_enEC (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development. Summary Report. Synthesis of the Evaluation Components of the Enhanced AIR 2019: Chapter 7. Brussels, Belgium. 2019. Available online: https://enrd.ec.europa.eu/evaluation/publications/summary-report-synthesis-evaluation-components-enhanced-airs-2019-chapter-7_it (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- European Commission. CAP Strategic Plans–Proposal for a Regulation COM(2018) 392. 2018. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM%3A2018%3A392%3AFIN (accessed on 30 April 2021).

- European Commission. Financing, Management and Monitoring of the CAP–Proposal for a Regulation COM(2018) 393. 2018. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/it/document.html?reference=EPRS_BRI%282018%29628302 (accessed on 30 April 2021).

- European Commission. Strategic Plans, Financing, Management and Monitoring of CAP, Common Organisation of Markets–Impact Assessment Part 1 SWD(2018) 301. 2018. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=SWD%3A2018%3A301%3AFIN (accessed on 30 April 2021).

- Brunori, G. Tre obiettivi (più uno) per la Pac post-2020 (Three objectives (plus one) for the post-2020 CAP). Agriregionieuropa 2017, 48. Available online: https://agriregionieuropa.univpm.it/it/content/article/31/48/tre-obiettivi-piu-uno-la-pac-post-2020 (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Guyomard, H.; Bureau, J.C.; Chatellier, V.; Detang-Dessendre, C.; Dupraz, P.; Jacquet, F.; Reboud, X.; Requillart, V.; Soler, L.G.; Tysebaert, M. Research for the AGRI Committee–The Green Deal and the CAP: Policy Implications to Adapt Farming Practices and to Preserve the EU’s Natural Resources; Publications Office of the EU: Luxembourg City, Luxembourg, 2020; Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document.html?reference=IPOL_STU(2020)629214 (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- European Commission. Commission Staff Working Document. Analysis of Links Between CAP Reform and Green Deal. SWD/2020/0093. Brussels, Belgium. 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/food-farming-fisheries/sustainability_and_natural_resources/documents/analysis-of-links-between-cap-and-green-deal_en.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2021).

- Massot, A.; Negre, F. Towards the Common Agricultural Policy beyond 2020: Comparing the reform package with the current regulations. Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies, Directorate-General for Internal Policies. 2018. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/b0d66e13-30d9-11e9-8d04-01aa75ed71a1/language-en/format-PDF/source-118244956 (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Matthews, A. The EU’s Common Agricultural Policy Post 2020: Directions of Change and Potential Trade and Market Effects; International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development (ICTSD): Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, A. Introducing a Development Policy Perspective into CAP Strategic Plans. TEP Working Paper No. 0319; Trinity Economics Papers–Department of Economics: Dublin, Ireland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Carey, M. The Common Agricultural Policy’s new delivery model post-2020: National administration perspective. EuroChoices 2019, 18, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erjavec, E. CAP Strategic Planning: Scope and Implications. CAP REFORM. Europe’s Common Agricultural Policy is Broken–Let’s Fix It! 2018. Available online: http://capreform.eu/cap-strategic-planning-scope-and-implications/ (accessed on 25 November 2020).

- Erjavec, E.; Lovec, M.; Juvančič, L.; Šumrada, T.; Rac, I. Research for AGRI Committee–The CAP Strategic Plans Beyond 2020: Assessing the Architecture and Governance Issues in Order to Achieve the EU-Wide Objectives; European Parliament, Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Metta, M. CAP Performance Monitoring and Evaluation Framework: What’s Cooking? 2020. Available online: https://www.arc2020.eu/cap-performance-monitoring-and-evaluation-framework-whats-cooking/ (accessed on 30 April 2021).

- De Castro, P.; Miglietta, P.P.; Vecchio, Y. The Common Agricultural Policy 2021–2027: A new history for European agriculture. Ital. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2020, 75, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Guidance for Member States on Performance Framework, Review and Reserve; EU Publications Office: Luxembourg City, Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Council of The European Union. Proposal for a Regulation on CAP Strategic Plans–Commission’s Replies to Delegations’ Comments (Titles VII, VIII and IX). WK 9482/2018 ADD 6; Council of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Thoyer, S.; Préget, R. Enriching the CAP evaluation toolbox with experimental approaches: Introduction to the special issue. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2019, 3, 347–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, D.; Dwyer, J.; Hill, B. The evaluation of rural development policy in the EU. EuroChoices 2010, 9, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, J. Another reform of the common agricultural policy: What to expect. EuroChoices 2019, 18, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieck, C.; Hausmann, I. Indicators everywhere: The new accountability of agricultural policy? In Proceedings of the 172nd EAAE Seminar, Brussels, Belgium, 28–29 May 2019.

- Gocht, A.; Britz, W. EU-wide farm type supply models in CAPRI. How to consistently disaggregate sector models into farm type models. J. Policy Model. 2011, 33, 146–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louhichi, K.; Ciaian, P.; Espinosa, M.; Colen, L.; Perni, A.; Gomez y Paloma, S. The impact of crop diversification measure: EU-wide evidence based on IFM-CAP model. In Proceedings of the IAAE Congress, Milan, Italy, 9–14 August 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cagliero, R.; Cristiano, S.; Licciardo, F.; Varia, F. La Valutazione On-Going dei Psr 2007–13 Come Esperienza di Capacity Building (Ongoing Evaluation of the 2007–13 RDPs as a Capacity Building Experience). Agriregionieuropa 2017, 48. Available online: https://agriregionieuropa.univpm.it/it/content/article/31/48/la-valutazione-going-dei-psr-2007-13-come-esperienza-di-capacity-building (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Cristiano, S.; Tarangioli, S. Le Lezioni da Trarre Dalle Valutazioni di Sintesi Della Programmazione Dello Sviluppo rurale 2007–2013 (Lessons to be Learned from the Synthesis Evaluations of Rural Development Programming 2007–2013). Agriregionieuropa 2017, 48. Available online: https://agriregionieuropa.univpm.it/it/content/article/31/48/le-lezioni-da-trarre-dalle-valutazioni-di-sintesi-della-programmazione-dello (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Viaggi, D. Valutazione ex-Post dei Psr: “Mission Impossibile”? Ex-post Evaluation of RDPs: “Mission Impossible”? Agriregionieuropa 2018, 52. Available online: https://agriregionieuropa.univpm.it/it/content/article/31/52/valutazione-ex-post-dei-psr-mission-impossibile (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development. Investment Support under Rural Development Policy. Final Report. Brussels, Belgium. 2014. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/785e1d1d-0022-4bb9-bf35-adb25f0dd141/language-en/format-PDF/source-205262810 (accessed on 14 May 2021).

- Lovec, M.; Šumrada, T.; Erjavec, E. New CAP delivery model, old issues. Intereconomics 2020, 2, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, A.; Höjgård, S.; Rabinowicz, E. Evaluation of results and adaptation of EU rural development programmes. Land Use Policy 2017, 67, 298–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valverde, F.A.N.; Garcia, E.C.; Martos, J.C.M. Aportaciones a la evaluación de los programas de desarrollo rural (Contributions to the evaluation of rural development programmes). B. Asoc. Geógr. Esp. 2012, 58, 349–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

| Period | Regulations | Guidelines | Key Element | Orientations | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1988–2000 |

|

| Logic of intervention |

|

|

| 2000–2006 |

|

| Common evaluation questions |

|

|

| 2007–2013 | Reg. (EC) No. 1698/2005 |

| CMEF |

|

|

| 2014–2020 |

|

| EP |

|

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cagliero, R.; Licciardo, F.; Legnini, M. The Evaluation Framework in the New CAP 2023–2027: A Reflection in the Light of Lessons Learned from Rural Development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5528. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105528

Cagliero R, Licciardo F, Legnini M. The Evaluation Framework in the New CAP 2023–2027: A Reflection in the Light of Lessons Learned from Rural Development. Sustainability. 2021; 13(10):5528. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105528

Chicago/Turabian StyleCagliero, Roberto, Francesco Licciardo, and Marzia Legnini. 2021. "The Evaluation Framework in the New CAP 2023–2027: A Reflection in the Light of Lessons Learned from Rural Development" Sustainability 13, no. 10: 5528. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105528

APA StyleCagliero, R., Licciardo, F., & Legnini, M. (2021). The Evaluation Framework in the New CAP 2023–2027: A Reflection in the Light of Lessons Learned from Rural Development. Sustainability, 13(10), 5528. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105528