Abstract

The global aging problem has a serious impact on the sustainable development of society. China has become the country with the largest aging population in the world, 1.75 times that of the EU and 3.01 times that of the United States. Therefore, the question of how to develop elderly care services and institutions in China is critical. Based on data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), this paper details the residential preferences of the elderly, and uses a multinomial logistic regression model to analyze the influence of education level, health status, and income level on the residential preferences of the elderly in China. The results of the study are as follows: (1) From a spatial point of view, the residential preference of “living together” gradually increases from the northeast to the southwest. As for the choice of “nursing home”, northerners prefer to live in nursing homes more than southerners, especially in the northeast. (2) There are many personal factors that significantly affect housing preferences, such as education level, health status, income level, etc. (3) The development of socialized elderly care institutions should fully consider the preferences of the elderly. There are big differences in residential preferences in different regions and different cities, so the development of elderly care services should be adapted to local conditions.

1. Introduction

Population aging has become a global social problem. At the beginning of this century, China began to enter a stage of population aging, and the level of population aging has continued to increase since then. In 2016, the population over the age of 65 exceeded 150 million, an increase of 50 million since 2005. According to the latest data from the National Bureau of Statistics of China, the number of people over the age of 65 in China reached 176.03 million in 2019, and the elderly dependency ratio reached 17.8% [1]. China has become the country with the largest aging population in the world, 1.75 times that of the EU and 3.01 times that of the United States [2].

The 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China proposed the following: “Actively respond to the aging of the population, build a policy system and social environment for the elderly, filial piety, and respect for the elderly, promote the integration of medical and elderly care, and accelerate the development of the aging industry”. This sets the direction for the development of China’s policies towards the elderly in the new era. For a long time, the traditional family pension has been the most important pension model in China. Traditional Chinese families not only bear the responsibility of raising children, but also providing for elders. Since China’s reform and opening up, foreign family and life concepts have been introduced to China, which has had an impact on China’s own family and life concepts. The family structure has developed from multi-generational living together to miniaturization and coreization. At the same time, economic costs, living costs, and housing costs continue to increase. Many families may not be able to afford large houses to live together, which affects the elderly’s living choices. Third, the changes in birth policies and birth concepts have affected China’s demographic structure. Given the declining birthrate and aging population in China, the need for care of the elderly population is great, and the burden of care for children is very heavy. With the development of society and the continuous change in people’s values, with childcare at the core of family duties, traditional methods and concepts of providing for elders are being affected in an unprecedented manner. The transformation of the way of providing for the aged not only affects the quality of life of the elderly, but also intergenerational relations. A change in the way of providing for the aged reflects the values of the society as a whole and is related to the stability and development of the society. It is imperative to explore the socialization of family pensions and to promote a comprehensive pension model that involves the organic integration of a family pension, community pension, and social pension.

With the increase in the number and proportion of the elderly population, the problem of aging in China has become increasingly prominent. The problem of providing for the aged is a major issue because it involves society, economy, life, institutions, laws, etc. The absolute number and relative proportion of China’s elderly population are increasing day by day, so how to provide elderly people with diversified care services that meet their subjective residential preferences requires in-depth and systematic research.

China has the largest population in the world, and its elderly population is also the largest. How to develop China’s pension services and find a sustainable development path of China’s pension model is very important. A large number of scholars have carried out detailed analyses of China’s old-age care methods, but usually ignore the key factor of the subjective willingness of the elderly. This paper holds that the development of pension services in China should follow the subjective wishes of the elderly, rather than other factors. Therefore, this paper first studies the regional characteristics of the residential preferences of the elderly, then analyzes how various characteristics of the elderly and their children affect their residential preferences, and finally suggests how to develop eldercare patterns in China from the perspective of residential preferences. The purpose of this research is to discover the factors that affect residential preferences, actively guide the reform and innovation of pension methods, and provide theoretical and empirical references for solving pension problems.

The research in this article has very important practical significance. On the one hand, although many scholars have studied people’s living styles, living habits, etc., this article starts with the most important personal characteristics, analyzes the differences in the residential preferences of the Chinese elderly under different characteristics, and analyzes the differences in different regions. Few scholars have raised the issue of regional differences in China’s residential preferences, so this is the academic gap to be filled in this article. On the other hand, many scholars have conducted a lot of research on the ways and models of the elderly, but these studies usually ignore the residential preferences of the elderly. This subjective preference of the elderly is a novel perspective for studying the development of old-age care methods and models.

2. Background and Literature Review

2.1. Residential Preferences

Residential preferences generally refer to the subjective will of the elderly about their future living conditions, which includes the psychological expectations of the elderly about living situations and subjective preferences. In the traditional Chinese family concept, people’s preferred living preference is multi-generation living under one roof. In recent years, China’s residential preferences have undergone great changes, and there are also great differences in different regions. Goldstein discovered a phenomenon in 1990 that there is a special form of living with children for the elderly in China called “by turns”, in which the elderly rotate eating and sleeping between their sons’ residences [3]. In 2002, Zeng and Vaupel’s research results showed that multiple generations living together used to be the main living preference of this group [4]. Now, the most popular living arrangement is living close to children in the same community/neighborhood in China, followed by living with adult children.

In such residential preference studies, there are many factors affecting the choice of subjective preference that can be expressed quickly by scholars familiar with the field. However, the specific indicators selected by different scholars are quite different, so the research results of different scholars are also quite different. In order to control population heterogeneity, many demographic and socio-economic indicators had been added to analysis. For instance, with age, the probability of living with a spouse declines, and the odds of living alone and with children increase [5]. As the number of children increases, the possibility of living with them also increases [6]. People with higher education, income, and net worth are more likely to live alone or with a spouse because they have more resources to maintain an independent family [7]. Meng’s results showed that, regardless of the actual options available or the cost, older people prefer to live close to their children rather than to co-reside with them. Leekwanwoo’s results show that the socio-demographic variables and the current residential experience variables of prospective retirees have affected their residential preferences after retirement [8].

Except for one or two physical health indicators (e.g., functional status and self-rated health), the vast majority of prior studies did not include a full range of physical and mental health measures ([9,10]). As mental illnesses such as depression and cognitive impairment, as well as physical disorders such as illness, disability, and self-assessment of health, often occur simultaneously [11], it is necessary to have a comprehensive understanding of their impact on residential preferences. There is little knowledge of how health effects interact with other key determinants of living arrangements [12]. For instance, health decline may be more consequential in affecting the probability of and transition to co-residence with children among those without a spouse than those with. Indeed, Chappell has claimed that having a spouse is the “greatest guarantee of support in old age” [13]. Using data from a four-wave panel study of Japanese elderly people between 1987 and 1996, Brown et al. have shown that physical and mental health exerts significant effects on living arrangements even after controlling for socioeconomic factors [14]. The mental health status of widowed elderly people who choose to live alone, have their children in the same village/community, or only live with their grandchildren is significantly better than that of widowed elderly people who live with their grandchildren. Social support factors play a mediating role in the relationship between living arrangement and mental health [15]. Research on residential preferences has a great impact on older parents’ subjective well-being and urban community development planning, etc. Based on CHARLS data gathered in 2011, Chen investigated the determinants of preference for intergenerational co-residence and examined the effects of living arrangement concordance (i.e., a match between preference and reality) on the subjective well-being of older Chinese people, and they found that having living arrangement concordance improves older parents’ subjective well-being [16]. Based on the data from the 2014 CFPS survey, Huang finds that living with single children can increase the elderly’s happiness, while living with married children can reduce an elderly couple’s happiness. A possible explanation is that power struggles can occur between an elderly couple and married children, which could lead to more frequent conflicts and reduce the elderly’s happiness. Thus, they come to a conclusion that the effect of living arrangements on happiness is determined by the type of living situation with the children’s generation [17]. Chi found that it is not easy for the Hong Kong Housing Authority to provide elderly people with the accommodation they prefer. In Hong Kong, the elderly are not all satisfied with their present living arrangements, even if they are living with their children [18]. Guan et al. found that it was much more difficult for elderly adults with an unharmonious housing situation to enjoy their life [19]. Nursing home residents’ preferences for everyday living are the foundation for delivering individualized, person-centered care, which can help care providers to design preference-based care plans with confidence, without having to frequently re-assess preferences [20]. Residential preference is a critical factor that affects the well-being of the elderly, so it must be taken into account in real estate development and the construction of nursing homes.

Unlike in developed countries, where almost all elderly people have access to publicly provided social security, the family is the main source of support for elderly Chinese adults [21,22,23]. It is important to have a deep understanding of elderly people’s housing preferences. The aim of this study, therefore, is to provide a clear understanding of residential preferences and their associated factors among elderly people in China.

2.2. Eldercare Patterns

The subjective pension mode of the elderly can be divided into three types: self-supporting, children supporting, and government supporting. Self-supporting and children supporting can be divided into two categories according to residence: living together with children in the same city (“living nearby”), and living separately with children in the same city (“living independently”) [24,25]. Living arrangements and living preferences are two important factors for studying the elderly’s lifestyles.

Factors such as economic conditions, health status, filial piety concepts, and intergenerational support have a significant impact on the wishes of the elderly. Filial piety reduces the likelihood of choosing a nursing home for one’s parents, while the medical needs brought about by chronic diseases are one of the motives of the elderly [26]. Rural elderly people prefer to live with their children, or at least live near to them. On the condition of having their spouse accompany them, elderly people who depend on their children to support them in daily life tend to choose to live with their children. The model of community pension service should be developed in rural areas of China to alleviate the problem of insufficient pension institutions in rural areas [27].

In the United States, there are two main pension models, “full pension” and “half pension [28]”. Full care means that the elderly live in nursing homes full-time. The “half-care system” means that the elderly stay in nursing institutions during the day and return to their own homes at night, which can not only address the issues of loneliness and inconvenience, but also allows them to enjoy friendships in their later years [29].

Japan is a typical Asian country with a high degree of aging. The government attaches great importance to the elderly and has issued a series of policies to deal with eldercare, such as the Law on the Welfare of the Elderly, the Law on Health Care for the Elderly, and the Ten-Year Strategy for the Promotion of Health Care and Welfare for the Elderly [30]. The Japanese government also attaches great importance to the training of nurses, and some schools have set up special disciplines to train professional geriatric nurses. After three years of professional training and obtaining the relevant qualification certificate, they are guaranteed a job [31,32].

The most popular eldercare pattern in China is a family pension. It has the advantages of stability, sustainability, simplicity, practicality, and fitting into the local culture. The aging of the Chinese population has brought about a comprehensive challenge to the traditional family pension. There are many problems such as the increase in the number of empty nesters, policy lags, difficulty in raising funds, the imbalance between the development of the socialized pension and the family pension, and misunderstandings about family pensions [25,33,34]. Due to the spiritual consolations of the traditional Chinese family that cannot be replicated by socialized old-age care, a few studies suggest that the role of family old-age care should continue to be explored [35].

Overall, China’s old-age services are at an acceptable level. At the beginning of China’s reform and opening up, the level of economic development was low, and pension services were just emerging. In the 21st century, the pension service in China began to develop rapidly. The number of pension beds per 1000 elderly population was 30.53 in 2019 compared with 10.97 in 2005, a 2.03-fold increase [36]. However, statistics show that there are some problems such as uneven development and insufficient utilization of pension facilities. According to data released by the Ministry of Civil Affairs, the current pension services include urban old-age services, rural old-age services, social welfare homes, honorary homes, honorary military rehabilitation hospitals, demobilized military sanatoriums, community old-age service institutions, etc. The average year-end utilization rate of these pension services was 52.34%, 68.96%, 59.16%, 57.20%, 61.82%, 62.14%, and 68.75% [36], respectively. With the development of the pension service industry and the rapid aging of the population, some contradictions and problems have become increasingly prominent. In particular, there is a large gap between existing pension service facilities, the service model, service content, service quality, and the actual demand of the elderly for old-age services.

However, there is no denying that, no matter the preference of the American elderly for the “half care system” or the preference of the Chinese and Japanese elderly for home care, a single type of pension mode cannot meet the needs of the elderly. The traditional family pension is changing with the changes in residential preferences and living arrangements of the elderly.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data

The China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) is a high-quality micro-research database designed to collect detailed information on families and individuals from the middle-aged and elderly population in China. The CHARLS national baseline survey included 30 provincial-level administrative units across the country, excluding the Tibet Autonomous Region, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau [37]. It covered 150 county-level units, 450 village-level units, and about 10,000 households. After excluding missing data on residential preferences, the total sample size was 10,050.

This study divides the residential preferences into the following five situations: “living together”, “living nearby”, “living independently”, “nursing home”, and “other”. First is “living together”, which means the elderly person lives with adult children who take care of them. Second is “living nearby,” which means they do not live with adult children in the same house, but live in the same community or village. Third is living independently. Fourth is living in a nursing home. Fifth is other options besides the above. In the three cases of “living nearby”, “living independently”, and “nursing home”, the elderly do not live with their children, so this is collectively referred to as “separate residence”. The number of people who chose “other” was so small that it was ignored in the model analysis.

3.2. Variables

This article analyzes housing preferences from the aspects of education, health, and income. The independent variables in this article include the respondents’ education level, their children’s education level, their physical health, mental health, self-rated health, average income level, relative income level, and other indicators. The summary statistics of the main variables studied in this paper are shown in Table 1. The following analysis will analyze each indicator in turn.

Table 1.

Summary statistics for key variables.

First is the level of education. This article analyzes the impact of the education level of the interviewee (the parents) and their children on residential preference. Respondents generally have lower levels of education, mostly elementary school, elementary school, and high school. Usually, only the education level of the interviewee is considered in the model analysis, but this study found that the residential preference is significantly influenced by the education level of their children. The correlation coefficient R between the education level of the respondent and their children is 0.3598, |R| < 0.4, indicating that the correlation between them is weak.

Second is health status. A person’s health has multiple dimensions, so it is difficult to reflect the health status of all aspects based on a single indicator. This article divides health into three dimensions, namely, physical health, mental health, and self-evaluated health.

Physical health is the ability to complete the activities of daily life independently. This study selected five indicators from the questionnaire to measure this: “Due to health and memory problems, do you have any difficulties with preparing hot meals?”; “Due to health and memory problems, do you have any difficulties with shopping for groceries?”; “Due to health and memory problems, do you have any difficulties with making phone calls?”; “Due to health and memory problems, do you have any difficulties with taking medications?”; and “Due to health and memory problems, do you have any difficulties with managing your money, such as paying your bills, keeping track of expenses, or managing assets?” A low index indicates that the respondent has a strong ability to take care of themselves and can handle affairs in life independently. A higher index indicates significant living difficulties, and the need for care from children or in a nursing home. In subsequent data processing, we defined having one or more answer of “impossible” as being unable to live independently.

Mental health is an important part of the health of the elderly, including loneliness, worry, fear, loss, insomnia, frustration, etc. The degree of mental health can be measured by the duration of the above indicators, such as the number of days the respondent feels depressed, etc. The positive indicators such as “hopeful for the future” and “I am happy” in the questionnaire can be used to measure the depression of the elderly after transformation. The transformation formula is Equation (1). In this study, these 10 indicators were transformed and added together to obtain the mental health level of the interviewee. The range of mental health level is 10–40, with the maximum value of 40 indicating serious mental health problems. This article divides the mental health status into groups and analyzes the influence of different levels of mental health status on the residential preference.

Self-rated health refers to your own evaluation of your health level. It is largely influenced by the respondent’s own medical knowledge. A respondent who lacks medical knowledge may ignore their own disease, while a respondent with deep medical knowledge will make a more accurate assessment of their own health level. In order to improve the accuracy of the self-evaluation of health, the questionnaire is designed to ask about it twice. First, at the beginning of the health status section, the interviewee is asked about their own health evaluation, and after a lot of medical inquiries, the interviewee is asked again. The two questions in the questionnaire are very similar; one is “Next, I have some questions about your health. Would you say your health is excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?” and the other is “Please think about your life as a whole. How satisfied are you with it? Are you completely satisfied, very satisfied, somewhat satisfied, not very satisfied, or not at all satisfied?” This design enables respondents who lack medical knowledge to reassess their health level, thereby improving the quality of the questionnaire. This article selects the data from the second query and merges the data from the control group for analysis.

Third is household income. Household income is an important measure of household economic level. Household income refers to the total income of household members and tenants in the house selected by random sampling, which makes random sampling more accurate and avoids systematic errors. This article divides it into two types, namely, household’s actual income and household’s relative income. The actual income of a household is an absolute quantity: the average value of the real income of the household divided by the number of people living there. This article defines household income higher than 5000 yuan as 1, income between 500–4999 yuan as 2, and income less than 499 yuan as 3. As a relative quantity, the relative income of a household is a person’s subjective evaluation of their own income. Generally speaking, the income is large for rich areas, but small for poor areas, so this study will analyze the difference between the two in the research model.

3.3. Methodology

When the results of research are represented by binary or categorical variables, the use of logistic regression is very common in social science research. In sociological research, the interpretation of logistic regression involves more technical difficulties than multivariate linear regression. The latter is easy to calculate and can be explained very well [38]. It is also a quantitative method recommended by textbooks when sociologists face various dichotomous dependent variables [39]. Choosing appropriate methods and indicators to explain the results can solve many practical problems, so logistic regression should be widely applied in the fields of social epidemiology and public health research to solve more real-life problems [40].

This paper selects the multinomial logistic regression model to analyze the impact of a respondent’s education level, the level of education of the respondent’s children, household income, relative income, physical health, mental health, and self-rated health on living preferences for the elderly. Taking “living together” as the reference group, we analyzed the differences between the conditions of “living nearby”, “living independently”, and “nursing home”. In addition, the analysis of residence preference should consider the question of the intergenerational relationship and whether there is a spouse. First, whether the intergenerational relationship is harmonious will affect the living arrangements of the elderly to a large extent. Families with good intergenerational relationships may be more inclined to live together, but whether the intergenerational relationship is harmonious is difficult to quantify. Second, for the elderly, whether they have a spouse to accompany them will also affect whether they live with their children and how they will arrange their future residence. The CHARLS questionnaire directly added the assumption of a “harmonious relationship with children” in the questions, which can eliminate the interference of intergenerational relationships. As to the question of whether there is a spouse, follow-up research will separately study the differences between the two conditions.

The multinomial logistic regression model uses the logit connection function to analyze the problem of the dependent variable being a categorical measurement, and its independent variable can be a continuous variable or a categorical variable. The multivariate logit model can be regarded as an extension of the binary logit model. It can be regarded as the simultaneous estimation of multiple binary logit models formed by pairing various selection behaviors in the explained variable. The following Equation (2) is the specific model formula.

where b is the selected control group, and J is the total number of categories included in the categorical variables, then j = 1, 2, 3, ..., J. After solving the above equations, the probability of each choice can be obtained. The following Equation (3) is the specific model formula.

4. Results

4.1. General Characteristics of Residential Preferences

First, we examined the education level of children and the living preference of the elderly. First of all, children’s education level is generally low, but varies greatly. The number of people who graduated from middle school was the largest, accounting for 35.24%. The number of people with primary school or middle school accounted for 49.77%, while 11.87% had a bachelor’s degree and only 2.16% had a master’s or doctoral degree. Secondly, it can be seen from Table 2 that the higher the education level of the children, the lower the rate of choosing “living together”. When there is a spouse and their children are illiterate, 80.00% of the elderly choose to live with their children; when the children’s education level is junior high school, 60.04% of the elderly choose living together; and when their children’s education is undergraduate level, the rate of choosing to live together drops to 45.82%. Under the condition of no spouse, when their children are illiterate, the rate of choosing to live together is slightly higher, reaching 80.56%. When the children’s education level is junior high school, 71.66% of the elderly choose living together, which is 11.62% higher than that of the elderly with a spouse. When the children’s education is undergraduate level, the rate of living together drops to 62.22%. With or without a spouse, the rate of cohabitation declined when education reached a bachelor’s degree, master’s degree, or doctoral degree, but the rate of cohabitation was higher for older adults without a spouse. On the contrary, the higher the education level of their children, the higher the rate of their parents choosing nursing homes—2.16% of the elderly with spouses choose to live in nursing homes, and 4.00% of the elderly without spouses choose to live in nursing homes. The probability of the elderly without spouses choosing nursing homes is higher (see Table 2).

Table 2.

The residential preferences of the elderly based on the different education levels of their children.

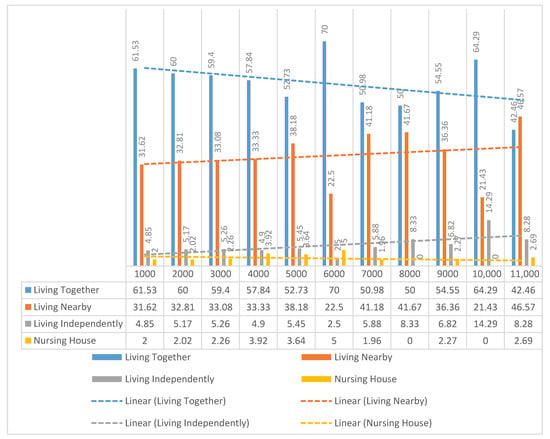

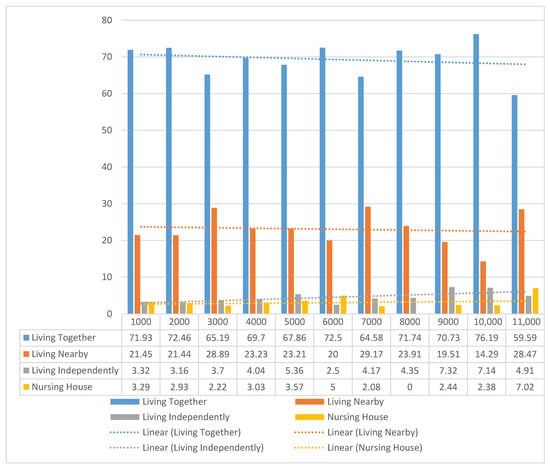

Secondly, the residential preferences of the elderly vary greatly under different income conditions. For elderly people with a spouse, the higher the income, the lower the rate of choosing to live with children; however, the proportion of choosing to live nearby is gradually increasing. Elderly people with a spouse whose income is between RMB 5000 and RMB 6000 prefer to live in a nursing home. Elderly people with an income of less than RMB 1000 have the lowest rate of living in nursing homes, less than half that of the former (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The residential preferences of the elderly with spouse at different income levels ((RMB) per month).

For the elderly without a spouse, the higher the income, the lower the rate of cohabitation, which is the same as for the elderly with a spouse. However, the proportion of elderly people without a spouse who choose to live with their children or in a nursing home at the same income level is higher than that of elderly people with a spouse (see Figure 1 and Figure 2). The rate of co-living for the elderly without a spouse at the same income level is higher than that of the elderly with a spouse. Elderly people without a spouse, whose income is between “5000–6000 yuan” and “10,000 yuan or more”, are most inclined to live in nursing homes.

Figure 2.

The residential preferences of the elderly without spouse at different income levels ((RMB) per month).

The third area we explored is the health status and residential preferences of the elderly. The elderly with a spouse in China generally enjoy good health; 81.30% of the elderly can take care of themselves, while 13.2% cannot live independently and need the care of their families to maintain a normal life. With or without a spouse, the worse the health, the higher the rate of cohabitation. Given the same physical health, the elderly without a spouse are more inclined to live with their children. The proportion of the elderly without a spouse who cannot live independently and choose to live with their children is 64.33%, while the proportion of the elderly without a spouse who cannot live independently (physical health level 3) and choose to live with their children is 73.25% (see Table 3). For those unable to live independently, those without a spouse were 1.55 times more likely to live in a nursing home than those with a spouse.

Table 3.

The residential preferences of the elderly under different physical health conditions.

4.2. Regional Differences in Residential Preferences

The elderly in different regions of China have different preferences for their future living situation. As there are no residential preference data for Tibet Autonomous region and Ningxia Hui Autonomous region in the CHARLS database, this paper will omit them.

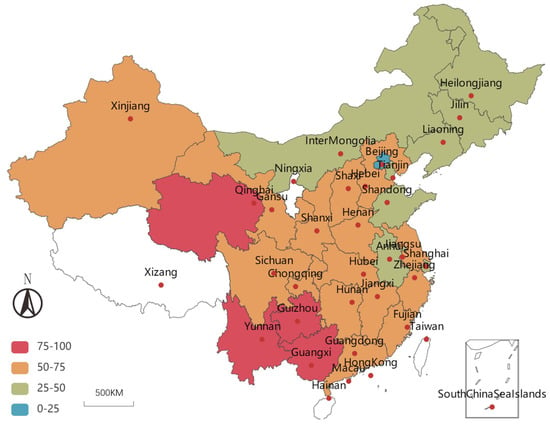

4.2.1. Regional Differences in the Elderly’s Choice of “Living Together”

Generally speaking, the willingness of Chinese elderly to choose “living together” is relatively strong. From a spatial point of view, it is gradually increasing from the northeast to the southwest. Northeast China provinces such as Heilongjiang, Jilin, Liaoning, and the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region showed the least interest in “living together”, with 31.16%, 45.45%, 39.30%, and 41.61%, respectively. People in Beijing, the capital of China, had the lowest rate of choosing “living together”, as low as 15.22%. In southwestern China, such as Yunnan, Guizhou, and Guangxi provinces, home care rates are very high, at 75.47%, 76.15%, and 75.07%, respectively. Qinghai Province, located in the west of China, has the highest home-based care rate in the country, reaching 86.02% (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The percentages of residential preference for “living together” in China.

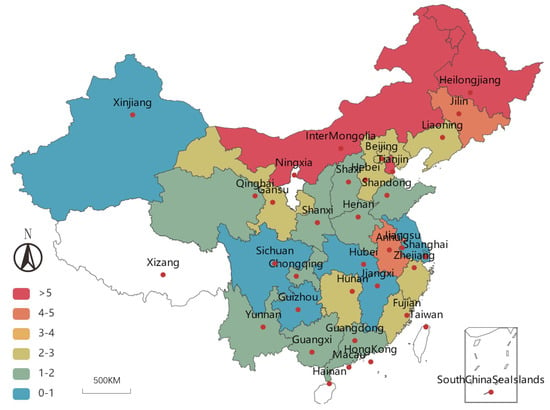

4.2.2. Regional Differences in the Elderly’s Choice of a Nursing Home

Overall, northerners choose to live in nursing homes more often than southerners, especially in the northeast. From the northeast to the southwest, there is a U-shaped relationship. Elderly people in Heilongjiang Province and the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region prefer to live in nursing homes, at 6.51% and 5.38%, respectively. Elderly people in Jiangxi, Sichuan, Jiangsu, and Hubei provinces in the central region have lower preferences for living in nursing homes, at 0.75%, 0.87%, 0.89%, and 0.92%, respectively. Elderly people in the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, Shanghai, and Guizhou Province choose not to live in nursing homes—the rates in all three provinces are 0%. The elderly in Guangdong Province, Yunnan Province, and the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region are more willing to live in nursing homes than the abovementioned central regions, at 1.93%, 1.90%, and 1.66%, respectively (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The percentages of residential preference for a nursing home in China. (Note: As there are no residential preference data for Tibet Autonomous region and Ningxia Hui Autonomous region, etc. in the CHARLS database, we set these areas as white).

4.2.3. Urban, Rural, and Regional Characteristics of the Residential Preferences of the Chinese Elderly

First of all, “living together” is the preferred mode of living for the elderly in China: 57.64% of the elderly nationwide prefer to live with their children. The proportion of people in the western region who prefer to live with their children accounted for about 64.18%, which is higher than the national average. The northeast has the lowest proportion, at only 38.74%. The rate of choosing “living nearby” came second. The rate of choosing “living nearby” was the highest in the northeast, reaching 45.71%, which is higher than the national average (33.61%). Third, with regard to the choice to live in a nursing home, residents in the northeast had the highest rate, 2.22-fold, 2.40-fold, and 2.22-fold that of the eastern, central, and western regions, respectively (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Living preferences by region: urban versus rural areas.

4.3. Analysis of Residential Preference for the Aged

4.3.1. Factors Influencing the Residential Preference of the Elderly with Spouses

The residential preferences of elderly people with spouses are shown in Table 5. The following is a brief analysis of the results.

Table 5.

Factors influencing the residential preference of the elderly (with spouse).

First, we found that age has a significant effect on the residential preference of the elderly with a spouse, and the older they are, the more likely they are to choose the “living nearby” and “living independently” options. In the traditional Chinese family framework, three or four generations living together is a sign of the harmony and happiness of the family [22,23,24], and parents are more willing to live with their children. From 1930 to 2010, the proportion of third-generation households and above decreased significantly, while the proportion of first- and second-generation households increased [39]. With ongoing changes in the social environment, economic situation, and family concept, people are more inclined toward separate living. The living preferences of the elderly in China are consistent with the changes in family structure in recent years. Under the separate type of living, parents and offspring have independent living space, so conflicts caused by differences in living habits will be greatly reduced, and intergenerational disagreements and estrangement will also be alleviated. When parents live close to their children, distance does not affect communication and companionship, and it is easy to provide support when they need help or have accidents, which is beneficial to both parents and children. The older the parents are, the greater the differences in lifestyle and eating habits between parents and offspring. At the same time, if grandchildren are taken into account, the living together option requires more living space. Therefore, the older the parents, the more inclined they are to choose separate living.

Second, the higher the educational level of the children, the more they prefer to live in separate homes (“living nearby”, “living independently”, or “living in nursing homes”). The research results of A and B are consistent with this article [6]. This index passed the significance test at the 1% level. Respondents’ education level and their children’s education level have the same effect on living preferences. This indicator has passed the significance test with a significance level of 10% (except for “living nearby”). The correlation coefficient (Pearson) between the respondents’ education and children’s education in the CHARLS data is 0.3598, indicating that there is no correlation between the two. The higher the education level of the children, the stronger their ability to obtain higher levels of employment and income, and the stronger their ability to control their lives. They can buy a house and move out of a city to live, or pay for a nursing home for their parents to achieve independence in a separate residence; at the same time, their children can achieve better development through independent living, which also meets the expectations of parents for their children.

Third, compared with “living nearby” and “living independently”, the lower the actual income of the interviewees, the more they prefer to “live together”; however, the income level of the interviewees does not seem to affect the choice of elderly care institutions for those with spouses. Seniors with spouses with higher incomes do not like to live independently. William A. V. Clark’s study is somewhat different from the research in this article. Clark’s study shows that Black Americans with increasing income show a distinct shift to greater willingness to live in integrated settings but also a distinct shift to own-race selections with second choices for neighborhood composition [40]. Since parents and children can have major differences in terms of ideology, values, etc., it is perhaps inevitable that there will be a generational gap, and so it is necessary to maintain relatively independent living spaces. The higher the income of the interviewee, the stronger their ability to purchase housing, and the easier it is to achieve “living nearby” and “living independently”. Income is not a limiting factor for living in a nursing home. Although living in a nursing home can involve professional rehabilitation and medical services, elderly people with spouses generally do not want to live in a nursing home.

Fourth, physical health and mental health have a significant impact on the residential preferences of the elderly, while self-rated health status has no significant impact. First of all, in terms of physical health, elderly people who have a spouse but cannot live independently are more inclined to live with their children. This conclusion is similar to that of A in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada [14]. The self-care ability of the elderly measures their skills of daily living. The worse their self-care ability, the more inclined they are to live with their children. Generally speaking, most people work outside the home and are unable to accompany their parents at all times, and do not have professional nursing skills. Elderly people with poor self-care ability need professional nursing staff in a nursing home, but the poorer the self-care ability of the interviewees who have a spouse, the more they want to live with and receive care from their spouse or other family members, rather than from strangers. Secondly, mental health has a significant impact on “living nearby”, “living independently”, and “living in nursing homes”. The worse their mental state, the less likely the elderly are to live with their children, and thus the probability of choosing “separate living” will increase. Communication with their children gives the elderly emotional sustenance. In this situation, their mental health is relatively good, making them more willing to live with their children. On the contrary, when they have poor mental health, the elderly prefer to live in a nursing home. These elderly spouses with poor mental health tend to prefer “separate living”, yet family members’ financial support, daily companionship, life care, emotional support, etc. could significantly improve their mental health. Finally, the impact of self-rated health status on housing preferences is not significant. Self-evaluated health status is restricted by the respondents’ level of medical knowledge. Although the “second question” in the questionnaire can improve the accuracy of the data, the respondent’s lack of medical knowledge can lead to an incorrect evaluation of their own health, and thus there would be a gap between the description of the health condition and the actual condition.

4.3.2. Factors Influencing the Residential Preferences of the Elderly with Spouses

The detailed results of the residential preferences of the elderly without spouses are shown in Table 6. A spouse and children are the main companions and communication partners for the elderly. The elderly have different caregivers and experience differences in daily life depending on whether or not they have a spouse. Therefore, it is necessary to analyze the residential preferences of the elderly without a spouse.

Table 6.

Factors influencing residence preference (no spouse).

It can be seen from Table 5 that the impact of indicators such as the age of the respondents and the education level of their children is similar to that of the elderly with a spouse. Relative income, physical health, and mental health have a significant impact on the choice of a nursing home for the elderly without a spouse.

First, compared with “living nearby”, the lower the income of the interviewees, the more likely they are to live with their children; however, the income level does not affect the choice of living in a nursing home for the elderly without a spouse. When there is no spouse in the picture, children are the main emotional sustenance, and living with them is the first choice for the elderly. However, due to differences in living habits and intergenerational conflicts, living close to children is also a good choice, as it not only achieves better communication and care but can help people to avoid intergenerational conflicts.

Second, elderly people without a spouse with poor mental health prefer to live in nursing homes. Problems such as loneliness, worry, fear, loss, and insomnia seriously affect the mental health of the elderly. Especially if the parent has lost their spouse, children should spend more time with the parent and provide them with financial, practical, and emotional support.

Third, the elderly without a spouse who cannot take care of themselves prefer to live in nursing homes. This is similar to Chappell’s research conclusion, who claimed that having a spouse is the “greatest guarantee of support in old age” [13]. Elderly people with a spouse who are in good health choose to live separately because of their children’s different eating habits and lifestyle. For the elderly without a spouse who cannot take care of themselves, choosing to live together may cause more trouble for their children. Physical care and other aspects require children to expend a lot of time and energy, which can become a burden. Therefore, living in a nursing home is a choice that arises out of helplessness and desperation.

5. Discussion

The residential preference in China used to be multi-generation living under one roof [22,23,24] or “by turns” [4]. Now with the development of society, there are obvious differences in residential preferences between different regions. Hong Kong has a Westernized society that has adopted the value system associated with the West [19]. Although these new values affect the younger generation more than the older one, a growing preference among the Hong Kong elderly to lead an independent life has been observed in recent years [41,42,43]. Since the elderly in Taiwan like to live with their children or other family members, especially if they are sick or disabled, stressful experiences and friction between generations can emerge at this time [24]. Not only are the residential preferences in China affected, but the residential preferences in other countries are also affected by personal characteristics and family characteristics. Holmlund’s research in Sweden shows that for aging parents, having fewer children reduces the probability of having at least one child living nearby, which is likely to have consequences for the intensity of intergenerational contact and eldercare [44]. Bai et al. studied the impact of Location Attributes on Residents’ Preferences and Residential Values in Hong Kong, and they found that little attention has been paid to residents’ demands in high-density and compact urban areas [45]. Kim’s research on Japan and Korea found that determinants of living arrangements of the elderly parents and married children are rough for not only the needs of elderly parents but also married children [46].

Chinese cultural patterns of living arrangements for the elderly are rooted in the tradition of filial responsibility [31,47,48]. Many scholars have observed that Chinese societies place an emphasis on Confucian doctrine—in this case, Xiao, or filial piety, which involves absolute love and respect for one’s parents and ancestors [24,25,49,50]. The analysis of the residential preferences of the elderly in China shows that, on the one hand, family support will still play an important role in the future. On the other hand, we should actively promote the development of socialized elderly care to adapt to the diversified choices of elderly care methods in an aging society. The CHARLS data show that, overall, 57.64% of the elderly prefer to live with their children, 33.61% prefer to live nearby, and 2.31% would choose to live in a nursing home. This is far from the goals and requirements of the aging service development plan issued by some local governments in China. Beijing’s “Twelfth Five-Year Plan” for the “Elderly Career Development Plan” put forward the “9064” old-age service model and new goal—that is, that by 2020, 4% of the elderly will live in an old-age service institution for centralized care. However, the results of this article show that, in terms of the subjective residential preferences of the elderly in China, only 2.13% of the elderly would choose to live in a nursing home. Among them, the ratios of the elderly in the eastern, central, western, and northeastern regions expressing a preference for a nursing home are 1.90%, 1.27%, 1.45%, and 2.55%, respectively, all of which are lower than the rate of institutional pensions in the “9064” model. Beijing is a region with a serious aging population problem. In 2015, Beijing’s aging career development plan clearly espoused the new “9064” old-age service model. In 2005, Shanghai took the lead in proposing the “9073” elderly care model, in which 3% of the elderly will reside in elderly care institutions. There is a big difference between Shanghai’s elderly care service development plan and its elderly population’s living preferences in that there were no respondents in Shanghai who chose to live in nursing homes per the CHARLS data.

How can we generalize about the residential preferences of the elderly when their personal characteristics and family characteristics are quite different? Moreover, how can we plan for the development of the pension model when the economic development in different regions is quite different? This is an urgent problem we are facing now. Elderly people who choose to live in a nursing home not only get professional care services, but also can communicate with other elderly people to improve their mental state. China has the largest number of elderly people in the world, so eldercare services are both a new development opportunity and a new challenge.

We have analyzed this problem from three aspects in this article. First of all, the elderly who are willing to live in nursing homes (2.13%) are the main service targets of the elderly care institutions. The development of socialized elderly care institutions should fully consider the preferences of the elderly. Second, consideration should be given to the residential preferences of the elderly in special circumstances. Some elderly people who are unable to take care of themselves still hope to receive care from their children and spouses, but if their relatives are not around or are unable to take care of them, their hopes cannot be realized and they can only choose a nursing home. Those elderly people who are forced to choose nursing homes should be taken into account in determining the service needs of the elderly in general. Finally, the development of elderly care services should be adapted to local conditions. There are big differences in living preferences in different regions and different cities. We should select the target population based on the elderly’s living preferences to develop the elderly care service industry.

6. Conclusions

Based on a systematic analysis of relevant research results, this paper constructs a multinomial logistic regression model of elderly residential preferences, and systematically studies the characteristics and factors influencing of these preferences. This article verifies the relevant achievements of the academic community, and also adds in information on the new characteristics and influence mechanisms of the residential preferences of the elderly, including the following conclusions.

First, the residential preferences of the elderly vary greatly between different provinces or regions. The willingness of the Chinese elderly to choose “living together” with their children is relatively strong. From a spatial point of view, this preference gradually increases from the northeast to the southwest. As for the choice of a nursing home, northerners choose nursing homes more often than southerners, especially those in the northeast. From the northeast to the southwest, there is a U-shaped relationship.

Second, the education level of children is the most significant factor that affects the preference of the elderly for “separate living”, and these conclusions are consistent with and without a spouse. The higher the education level of the children, the stronger their ability to obtain higher levels of employment and income, and the stronger their ability to control their lives. They can buy a house, move outside of a city to live, or pay for a nursing home for their parents; at the same time, the children can achieve better development through independent living, which also meets the expectations of parents for their children.

Third, there are differences in terms of the impact of physical health on the residential preferences of the elderly with or without a spouse. A spouse and children are the most important companions for the elderly in their later years, especially a spouse, who can provide care and comfort when the elder cannot live independently. For elderly people with a spouse, those who cannot live independently are more inclined to live together (expb = 0.79). In this situation, a spouse can take care of their partner without the need for the children to devote their time to care. Without a spouse, elderly who cannot live independently are more inclined to live in nursing homes (expb = 1.70), where they are taken care of by professional nursing staff. On the one hand, most of their children work outside the time and are thus unable to accompany their parents at all times, and do not have professional nursing skills. On the other hand, the interviewees want to live with their children and receive care from their families, rather than from strangers. However, if they are unable to take care of themselves, cohabitation will cause more trouble for their children. Physical care requires children to expend a lot of time and energy, which can become a burden to them. Therefore, living in a nursing home is a choice that arises from helplessness and desperation.

Fourth, the worse the mental health of the elderly, the less likely they are to live with their children. The worse the mental health of an elderly person without a spouse, the higher the probability that they will choose to live in a nursing home. The poorer the mental health of the elderly with a spouse, the higher the probability that they will choose to live apart (“living together”, “living nearby”, or “living independently”). Communication with their children gives the elderly emotional sustenance. In this situation, the mental health of the elderly is relatively good, which makes them more willing to live with their children. Conversely, in the case of poor mental health, the elderly prefer to live in nursing homes. These elderly people may express a preference for “separate living”, yet their family members’ financial support, companionship, care, emotional support, etc. will significantly improve their mental health.

Fifth, compared to “living nearby”, the lower the actual income of the interviewees, the more they prefer to live together. The conclusion is the same whether one has a spouse or not. Regardless of the presence of a spouse, the interviewee’s income level does not affect the choice of a nursing home; elderly people with a spouse and a relatively low income do not like to live independently, while elderly people without a spouse and with a relatively low income do not like living in a nursing home. Since parents and children can exhibit major differences in terms of ideology, values, etc., it is perhaps inevitable that there will be clashes of opinion, so it is necessary to maintain relatively independent living spaces. The higher the income of the interviewee, the stronger their ability to purchase and pay for housing, and the easier it is to opt for the “living nearby” option. At the same time, due to differences in living habits and intergenerational conflict, “living nearby” their children can not only achieve better communication and care, but also preclude intergenerational conflicts. Income status is not a limiting factor for choosing a nursing home. Although nursing homes provide professional rehabilitation and medical services, elderly people—with or without spouses—tend not to want to live in them.

Sixth, the development of China’s pension model is an important issue for families and society. We believe that a long-term and sustainable eldercare model is the path we should take. We should pay attention to all aspects of the life of the elderly, not just their physical and mental health, and think of appropriate ways to develop China’s pension services. The purpose of this strategy is to be in line with the subjective living preferences of the elderly, rather than basing decisions on existing pension institutions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.L., C.D. and M.D.C.; methodology, H.L., C.D. and M.D.C.; software, H.L., M.D.C. and C.D.; validation, H.L., M.D.C. and C.D.; formal analysis, C.D., M.D.C. and H.L.; investigation, C.D., M.D.C. and H.L.; resources, C.D.; data curation, C.D.; writing—original draft preparation, C.D., M.D.C. and H.L.; writing—review and editing, M.D.C., H.L. and C.D.; supervision, H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Jilin University Philosophy and Social Science Major Project Cultivation Project, “Research on the Long-term Balanced Development Strategy of Chinese Population”, grant number 2015ZDPY15.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

http://charls.pku.edu.cn/index/en.html (accessed on 12 May 2021).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Annual Query of National Data in China. Available online: https://data.stats.gov.cn/easyquery.htm?cn=C01 (accessed on 12 May 2021).

- Population Aged 65 and above (% of Total Population). Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.65UP.TO.ZS?view=chart (accessed on 12 May 2021).

- Goldstein, M.C.; Ku, Y.; Lkels, C. Household composition of the elderly in two rural villages in the People’s Republic of China. J. Crosscult. Gerontol. 1990, 5, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Vaupel, J.W.; Xiao, Z.Y.; Zhang, C.Y.; Liu, Y.Z. Sociodemographic and health profiles of the oldest old in China. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2002, 28, 251–273. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Kumar, K.A. Living Arrangement and Economic Dependency among the Elderly in India: A Comparative Analysis of EAG and Non EAG States. Ageing Int. 2019, 44, 352–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofstedal, M.B. Coresidence Choices of Elderly Parents and Adult Children in Taiwan; Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation; University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- McGarry, K.; Schoeni, R.F. Social security, economic growth, and the rise in elderly widows’ independence in the twentieth century. Demography 2000, 37, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, L.W.; Ji-Hyun, K. An Analysis on the Impact of Lifestyle on Preferred Housing after Retirement. Korea Real Estate Acad. Rev. 2018, 75, 87–100. [Google Scholar]

- Spitze, G.; Logan, J.R.; Robinson, J. Family structure and changes in living arrangements among elderly nonmarried parents. J. Gerontol. Soc. Sci. 1992, 47, S289–S296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilmoth, J.M. Unbalanced social exchanges and living arrangement transitions among older adults. Gerontologist 2000, 40, 64–74. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S.; Rodriguez, M.S. Pathways linking affective disturbances and physical disorders. Health Psychol. 1995, 14, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pendry, E.; Barrett, G.; Victor, C. Changes in household composition among the over sixties:Alongitudinal analysis of the health and lifestyles surveys. Health Soc. Care Community 1999, 7, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappell, N.L. Living arrangements and sources of caregiving. J. Gerontol. Soc. Sci. 1991, 46, S1–S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.W.; Liang, J.; Krause, N.; Akiyama, H.; Sugisawa, H.; Fukaya, T. Transitions in living arrangementsamong the elderly in Japan: Does health make a difference? J. Gerontol. Soc. Sci. 2002, 57, S209–S220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y. A Study on the Impact of Living Arrangement of the Widowed Elderly on Mental Health. Popul. Dev. 2018, 24, 113–121. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T. Living arrangement preferences and realities for elderly Chinese: Implications for subjective wellbeing. Ageing Soc. 2019, 39, 1557–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Duan, H. Differences between living arrangements and the happiness of the elderly. South China Popul. 2018, 33, 72–80. [Google Scholar]

- Chi, I. Living arrangement choices of the elderly in Hong-Kong. Asia Pac. J. Soc. Work 1995, 5, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.; Li, H.; Sun, H.; Wang, T.; Wu, W. The impact of a discrepancy between actual and preferred living arrangements on life satisfaction among the elderly in China. Clinics 2015, 70, 623–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, K.M.; Heid, A.R.; Kleban, M.; Rovine, M.J.; Van Haitsma, K. The Change in Nursing Home Residents’ Preferences Over Time. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2018, 19, 1092–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, X.Y.; Strauss, J.; Tian, M.; Zhao, Y.H. Living arrangements of the elderly in China: Evidence from the CHARLS national baseline. China Econ. J. 2015, 8, 191–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mindel, C.H.; Wright, R., Jr. Differential living arrangements among the elderly and their subjective well-being. J. Act. Adapt. Aging 1982, 3, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.-S.; Shih, Y.-C.; Li, Y.-T. Living arrangements, coresidence preference, and mortality risk among older Taiwanese. Asian Educ. Dev. Stud. 2017, 6, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, D. Retrospect and Prospect: Research on the Ways of Providing for the Elderly in China; Unity Press: Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Q. Research on China’s Pension System; Dalian Maritime University Press: Dalian, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, D.; Li, S.; Song, L. A Study on the Influencing Factors of Living Intention in Rural Elderly Nursing Homes in China. Popul. J. 2011, 1, 24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y. Research on Influencing Factors of Rural Elderly Housing Preference; Huazhong University of Science and Technology: Wuhan, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X. The experience and enlightenment of the home-based care in foreign countries—Taking the United States, Finland, Sweden, and Japan as examples. Spec. Zone Econ. 2013, 10, 49–50. [Google Scholar]

- Enchao, D. Experience and Enlightenment of Foreign Pension Industry Development; Henan University: Henan, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Heller, P.S. The challenge of an aged and shrinking population: Lessons to be drawn from Japan’s experience. J. Econ. Ageing 2016, 8, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horioka, C.Y.; Suzuki, W.; Hatta, T. Aging, savings, and public pensions in Japan. Asian Econ. Policy Rev. 2007, 2, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, T. Demographic transition in Japan. Soc. Sci. Med. Part A Med. Sociol. 1978, 12, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrientos, A. Pension reform, personal pensions and gender differences in pension coverage. World Dev. 1998, 26, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flume, W. From pension adjustment to pension capital. Betrieb 1973, 26, 1504–1506. [Google Scholar]

- Piao, X.-Y. A study on Community Care Model for the Elderly in Yanbian Area under the Internet⁺ Background. Chin. Stud. 2019, 69, 279–290. [Google Scholar]

- Data Comes from China Statistical Yearbook. Available online: https://data.stats.gov.cn/search.htm?s=%E5%BA%8A%E4%BD%8D%E6%95%B0 (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- Introduction to the Sample of Pilot Resurvey of CHARLS. Available online: http://charls.pku.edu.cn/pages/about/sample/zh-cn.html (accessed on 12 May 2021).

- Mood, C. Logistic Regression: Why We Cannot Do What We Think We Can Do, and What We Can Do About It. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2010, 26, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Li, L. Intergenerational Dynamics and Family Solidarity: A comparative study of mainland China, Japan, Korea and Taiwan. Sociol. Stud. 2009, 24, 26–53. [Google Scholar]

- Merlo, J. A brief conceptual tutorial of multilevel analysis in social epidemiology: Using measures of clustering in multilevel logistic regression to investigate contextual phenomena. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2006, 60, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.J. A Pilot Study on the Living-Alone, Socio-Economically Deprived Older Chinese People’s Self-Reported Successful Aging: A Case of Hongkong. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2009, 4, 347–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, D.R. Accommodation for elderly persons in newly industrializing countries: The Hong Kong experience. Int. J. Health Serv. 1988, 18, 255–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, N.; Chi, I. A study of living arrangements of the elderly in Hong Kong. Hong Kong J. Gerontol. 1990, 4, 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Holmlund, H.; Rainer, H.; Siedler, T. Meet the Parents? Family Size and the Geographic Proximity Between Adult Children and Older Mothers in Sweden. Demography 2013, 50, 903–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Y.X.; Song, J.S.; Wu, S.S.; Wang, W.; Lo, J.T.Y.; Lo, S.M. Comparing the Impacts of Location Attributes on Residents’ Preferences and Residential Values in Compact Cities: A Case Study of Hong Kong. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-N. Determinants of Living Arrangements of the Elderly Parents and Married Children in Japan and South Korea. Inst. Hum. Stud. 2009, 23, 5–29. [Google Scholar]

- Löckenhoff, C.E.; Lee, D.S.; Buckner, K.M.L.; Moreira, R.D.T.O.; Martinez, S.J.; Sun, M.Q. Cross-Cultural Differences in Attitudes About Aging: Moving Beyond the East-West Dichotomy; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Piovesana, G.K. The aged in Chinese and Japanese cultures. In Dimensions of Aging: Readings; Hendricks, J., Hendricks, C.D., Eds.; Winthrop: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979; pp. 113–120. [Google Scholar]

- Whyte, M.K. (Ed.) China’s Revolutions and Intergenerational Relations; University of Michigan Center for Chinese Studies: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton, A.; Lin, H.-S. Social Change and the Family in Taiwan; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).