Understanding Intangible Culture Heritage Preservation via Analyzing Inhabitants’ Garments of Early 19th Century in Weld Quay, Malaysia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

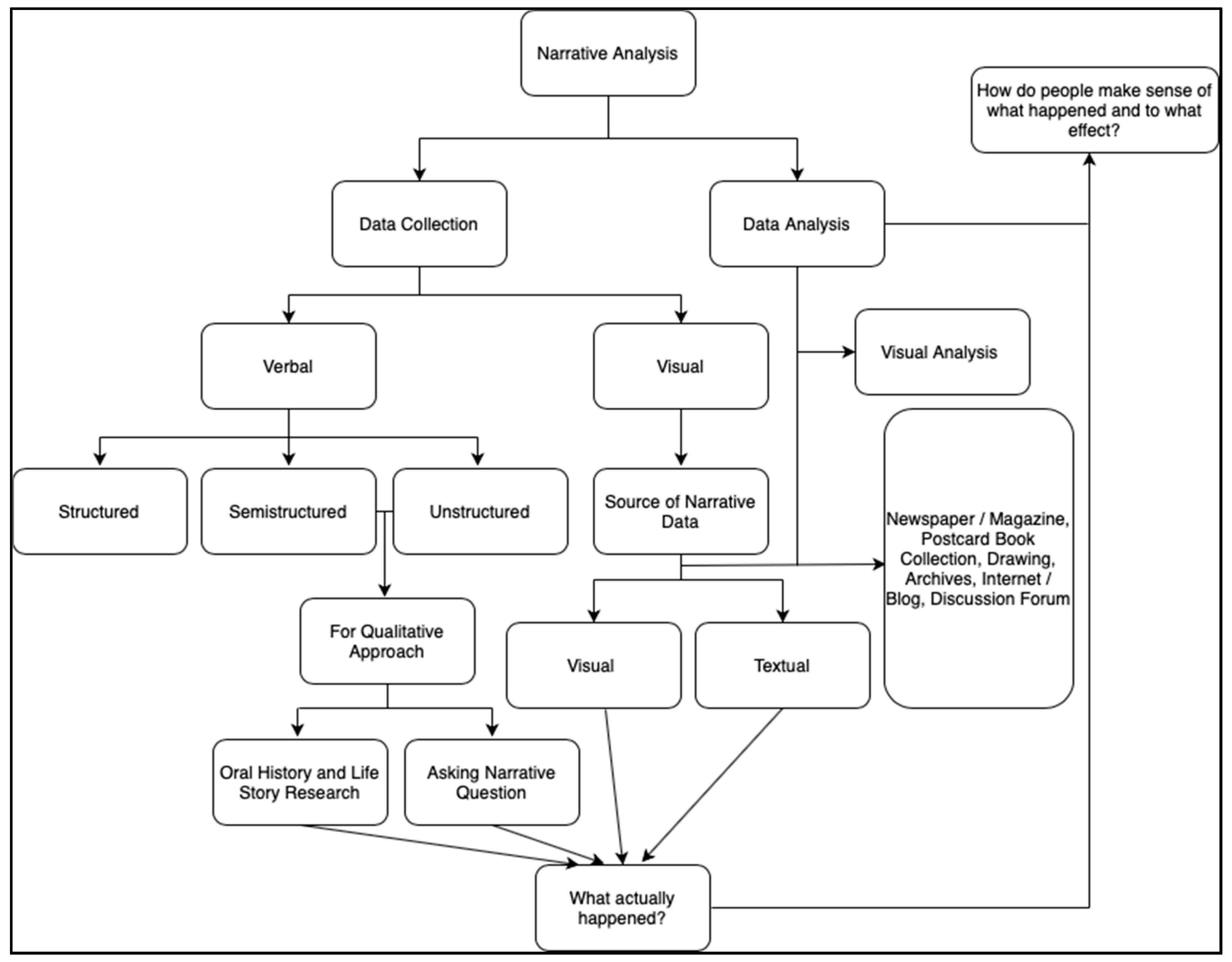

2. Narrative Analysis for Mining the Data of Material Culture

3. Interview Process

3.1. Background Study on Informant A

3.2. Background Study on Informant B

4. From Stories to Data Analysis

4.1. Narrative Stories Based on Informant A and His Grandfather

“I have seen those pants before as my father wore them too. The pants were called ‘ngau tau fu’.”(Inf A, 20-L119)

“It is like towel. Shui mang is a kind of cloth.”(Inf A, 21a-L111)

“They were pants, but the pattern of these pants was different from others. The waistband area was tied with long piece of cloth. The lower part of the pants was very broad.”(Inf A, 21b-L112)

“The main purpose is to ease the laborers when they were working, so that they could easily move while carrying the goods. It’s just like Bruce Lee’s costume in the movie.”(Inf A, 21c-L113)

“Yes! The upper part of the pants consists of shui mang. Whenever the laborers required much strength for carrying goods, they would tighten the knot of the shui mang. It is a long piece of cloth.”(Inf A, 21d-L115)

“…because there was no rubber at the waist. The top part of the pants will then be folded down and cover the shui mang.”(Inf A, 22a-L116)

“…so then laborers can keep money in the folded area, as they couldn’t bring a wallet with them.”(Inf A, 22b-L117)

“…Laborers wore black in color. They usually kept their upper body naked.”(Inf A, 23a-L92)

“You mean the mandarin jacket with fabric buttons?”(Inf A, 23b-L102)

“The mandarin jacket consists of four pockets. They wore it with a matching hat.”(Inf A, 23c-L95)

“They didn’t button up the jacket. The jacket was with buttons but it was not buttoned up. The people in the past wouldn’t wear two pieces of clothing due to the hot weather. Furthermore, the fabric of the jacket was very thick. It was as thick as canvas.”(Inf A, 24-L104)

“The mandarin jacket was in blue. The blue looked ugly. They normally dyed the fabric with blue color, just like the blue that is used in the logo of Barisan Nasional.”(Inf A, 25a-L93)

“This tone of blue was used in the past, as it was resistant to dirt. Dirt can be easily visible on lighter colored fabric. Moreover, they didn’t have strong detergent during that time. They only used soap to wash clothes.”(Inf A, 25b-L108)

“It was made in a factory, but there were limited choices of colors, such as brown, beige, and black…”(Inf A, 26a-L109)

“No, only long pants were available. They were mainly wooden brown and black in color. However, the main color for shirt was blue, white, and beige…”(Inf A, 26b-L121)

“…The fabric was dyed with dark color, so it could absorb heat easily…”(Inf A, 26c-L105)

“Cotton must be the only material used to make clothes because polyester was not available during that time.”(Inf A, 27a-L84)

“…Only cotton was available in the past. Another material widely used by people was Ma (linen).”(Inf A, 27b-L85)

“Ma (linen) has a rougher surface than cotton. Cotton and silk can be said as the best materials back then. Only these three materials were used in the past.”(Inf A, 27c-L86)

“…Those who dressed in white were policemen and government officers. However, the British usually wore shirts and short pants, which were both white in color. The short pants were so referred to as ‘ma yin tong’ in Cantonese.”(Inf A, 28a-L121)

“…There were many pleats found at the waist area because the lower part of the pants was very broad…”(Inf A, 28b-L122)

“I didn’t see any Malays in Weld Quay. It was rare. Maybe one or two Malays who were wearing songkok will show up there. There were many Chinese.”(Inf A, 29a-L126)

“There was also the Penang Acheh Association. There were quite a number of them around Weld Quay if you are talking about Malay ethnics from Acheh.”(Inf A, 29b-L127)

“Same as the native Malays, they normally wore sarung and songkok.”(Inf A, 29c-L128)

4.2. Narrative Stories Based on Informant B

“Hokkien…Hokkien…still Hokkien yeah! Hokkien people…Hokkien people in those days is about 40–50%, and Kwangtung, Cantonese is 20%, Teowchew is 15%, Hakka 8%.”(Inf B, 7a-L94)

“Kwangtung they don’t really find them… because you know Cantonese they are tin miners. Penang not many Cantonese.”(Inf B, 7b-L92)

“Before these clan jetties came about, they were staying in the like Stewart Lane… all these places… the coolie house. One house fifty to sixty people all back then.”(Inf B, 8-L12)

“Yes! Clan jetty is like a great doubt that they can carry heavy goods. Some clan jetties are only for charcoal. Like the last few one… the Yeoh Jetty is actually for charcoal.”(Inf B, 9a-L69)

“…Yeah… and it is very shaky and then they construct themselves and then they were poor Chinese. Where they have money to build a strong…err…this…err…pier. No, that’s not pier. So whether they really carry heavy goods and go through the clan jetty and you find opposite the clan jetty, they are not really warehouses. So this is more for residential. So the Chinese…from the clan jetty also go to the pier to get the things down…up and down lah.”(Inf B, 9b-L71)

“Yeah, the clan jetties are good example. Not all of them nah… Err… I think that Lee Jetty, Chew Jetty, Lim Jetty and most of the people work as the porters lah. Stevedores! We have a good call… stevedores! or you can call them as coolies.”(Inf B, 10a-L11)

“…the coolies are either Chinese or Indian carried all the goods to the… the gudangs.”(Inf B, 10b-L9)

“As in Kedah Malays stayed in the Seberang Perai.”(Inf B, 11a-L30)

“So… very few really crossed to the island side lah. So if we’re talking about Malay, there…many of them would be the Acheh Malay descendants.”(Inf B, 11b-L31)

“Okay…if you want to define Malay…err…In town, the urban Malay…there’s one from Acheh.”(Inf B, 11c-L28)

“Muslims err… they were…there is no record of showing them were working as the laborers because they were farmers. Paddy field…farmers…and fisherman in Tanjong Tokong.”(Inf B, 11d-L16)

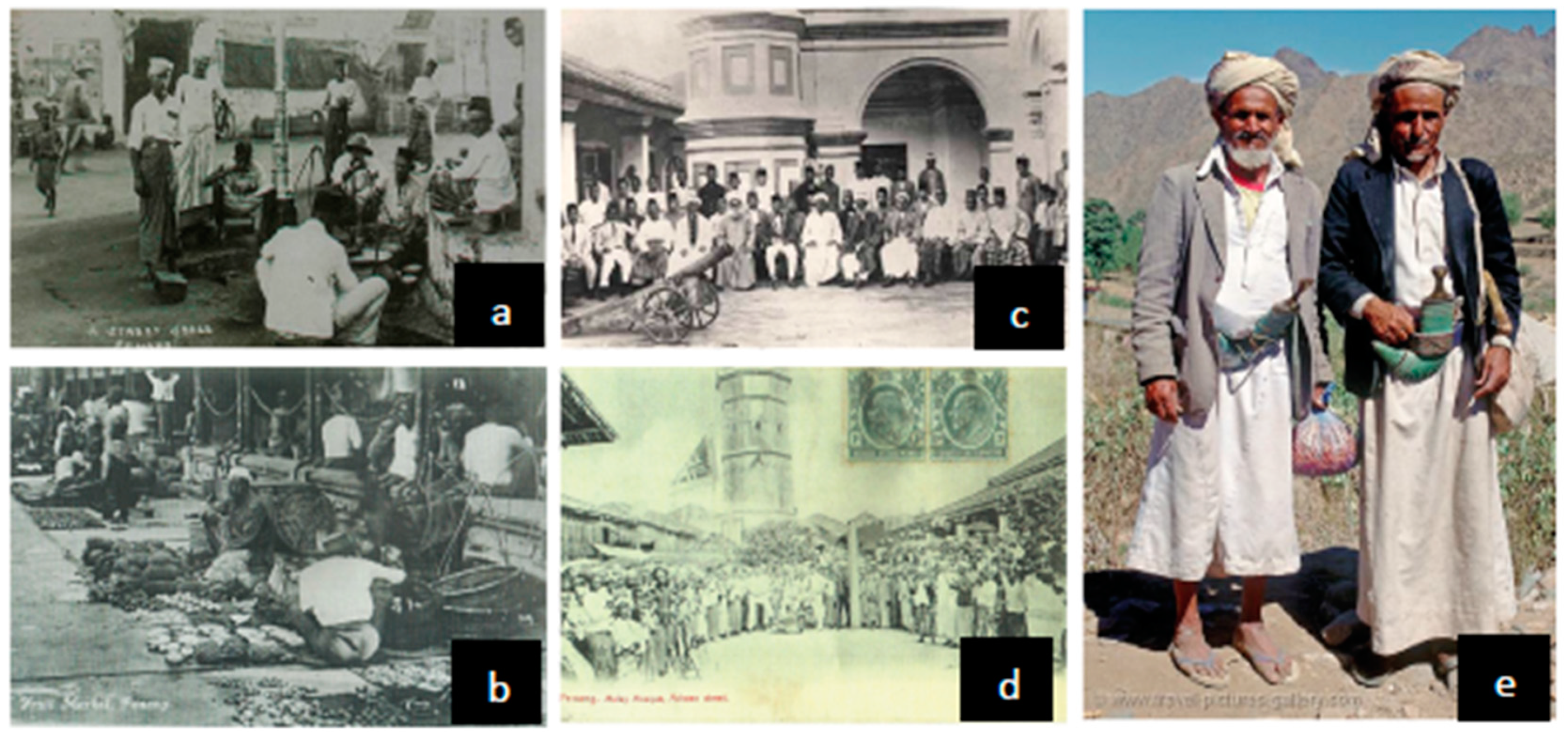

“We have to be more specific because…and then we also have the Jawi Peranakan. They are some mixed. Malay mixed with the Indian–Muslim, some also mixed with the Arabic. We have the mahadrami…Hadrami Muslim…is from Yemen. Actually they went through Acheh, and from Acheh, they came to Penang. Hadrami ya…Some are Arabs. So Muslim…We have to group them as Muslims. It’s so mixed already.”(Inf B, 12a-L32)

“…but those days what we meant the Muslim communities is err…ar Lebuh Acheh, setting up their printing shops. Some of the Malay in Jawi… the earliest comes in this countries to set up their printing bookshop.”(Inf B, 12b-L22)

“Arabic guys also… Hadrami ya…appear…yeah…The record shows 500 of them…by Acheh come to Penang and they want to set up like Acheh Mosque…all these things and a lot of them actually are Iman…and well-known.”(Inf B, 12c-L33)

5. Collaborative Analysis Process

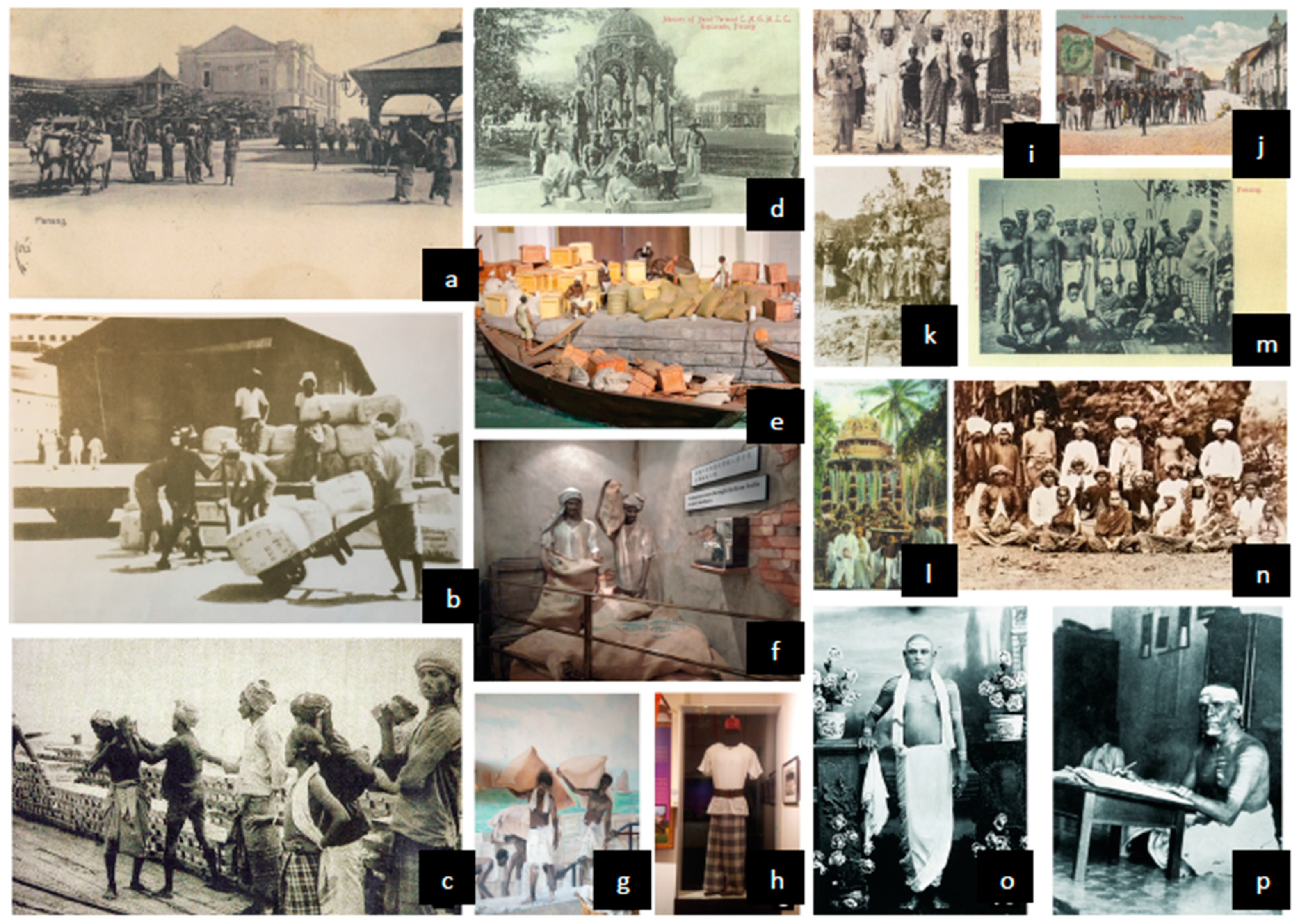

5.1. Garments of Chinese Ethnic at Weld Quay

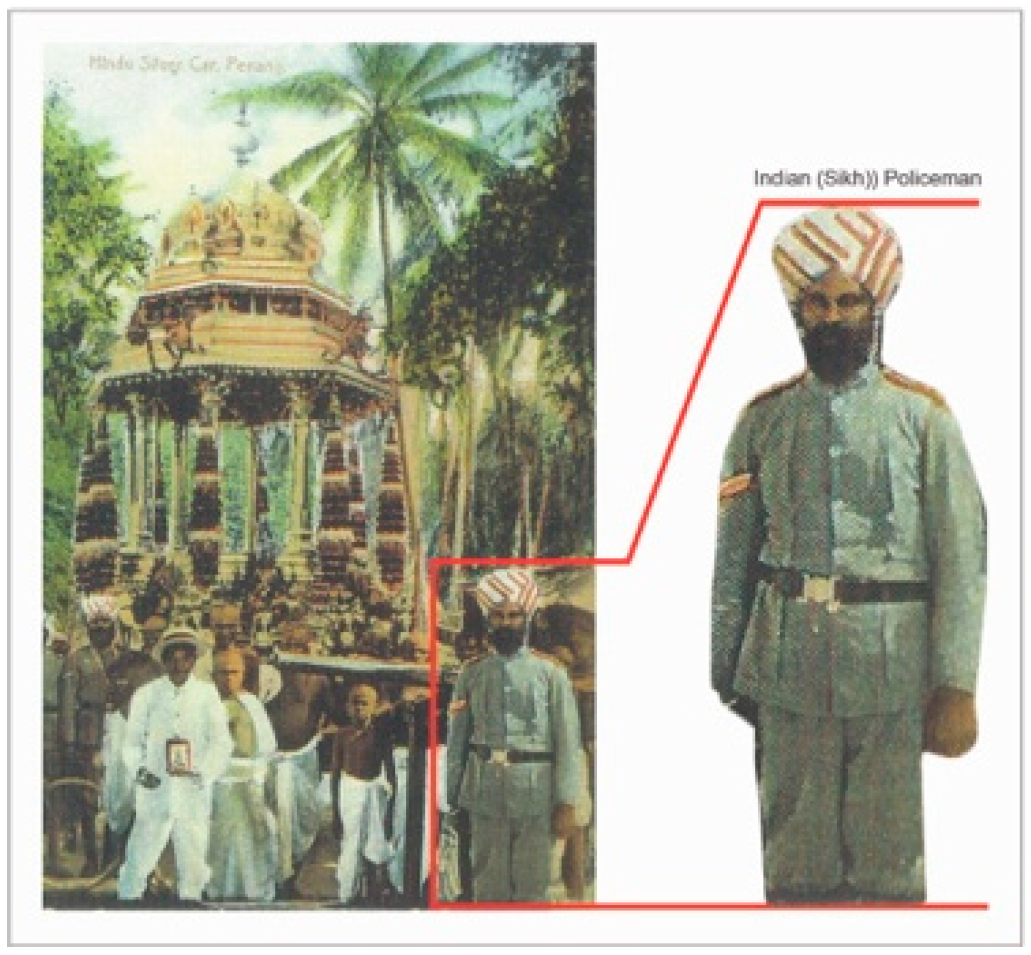

5.2. Garments of Indian Communities at Weld Quay

5.3. Garments of Malay Communities at Weld Quay

5.4. Garments of British or European Communities in Weld Quay

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. World Heritage List. 2016. Available online: http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/ (accessed on 18 February 2021).

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Melaka and George Town, Historic Cities of the Straits of Malacca. United Nations Educational Science and Cultural Organisation. 2017. Available online: http://whc.unesco.org/en/decisions/1486 (accessed on 24 March 2020).

- Lim, C.K.; Tan, K.L.; Zaidan, A.A.; Zaidan, B.B. A proposed methodology of bringing past life in digital cultural heritage through crowd simulation: A case study in George Town, Malaysia. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2020, 79, 3387–3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahani, B.M.; Abooali, G.; Mohamed, B. George Town world heritage site: What we have and what we sell? Asian Cult. Hist. 2012, 4, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Application of Jiangxi intangible cultural heritage in modern fashion design. In Proceedings of the 2017 3rd International Conference on Economics, Social Science, Arts, Education and Management Engineering (ESSAEME 2017), Huhhot, China, 29–30 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. 2009. Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/doc/src/06859-EN.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2021).

- Bortolotto, C. The Role of Spatiality in the Practice of the 2003 Convention; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2016; p. 46. [Google Scholar]

- Hafstein, V.T. Cultural heritage. In A Companion to Folklore; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 500–519. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, F. The Participation in the safeguarding of the intangible cultural heritage. Revista dos Sócios do Museu do Povo Galego 2018, 23, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, S. The Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage in England: A Comparative Exploration. Ph.D. Thesis, Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Laarse, R. Europe’s Peat Fire: Intangible Heritage and the Crusades for Identity. In Dissonant Heritages and Memories in Contemporary Europe; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 79–134. [Google Scholar]

- Idris, M.Z.; Syed Yusoff, S.O.; Mustaffa, N. Preservation of intangible cultural heritage using advance digital technology: Issues and challenges. J. Arts Res. Educ. 2016, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isa, W.M.W.; Zin, N.A.M.; Rosdi, F.; Sarim, H.M. Digital preservation of intangible cultural heritage. Indones. J. Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci. 2018, 12, 1373–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.K.; Cani, M.P.; Galvane, Q.; Pettre, J.; Talib, A.Z. Simulation of past life: Controlling agent behaviors from the interactions between ethnic groups. In Proceedings of the 2013 Digital Heritage International Congress (Digital Heritage), Marseille, France, 28 October–1 November 2013; Volume 1, pp. 589–596. [Google Scholar]

- Aristidou, A.; Stavrakis, E.; Chrysanthou, Y. Cypriot Intangible Cultural Heritage: Digitizing Folk Dances; Cyprus Computer Society: Nicosia, Cyprus, 2014; pp. 42–49. [Google Scholar]

- Foo, R.; Krishnapillai, G. Preserving the intangible living heritage in the George Town world heritage site, Malaysia. J. Herit. Tour. 2019, 14, 358–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, C.; Breheny, M. Narrative analysis in psychological research: An integrated approach to interpreting stories. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2013, 10, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Fina, A.; Georgakopoulou, A. The Handbook of Narrative Analysis; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kivunja, C.; Kuyini, A.B. Understanding and applying research paradigms in educational contexts. Int. J. High. Educ. 2017, 6, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meraz, R.L.; Osteen, K.; McGee, J. Applying multiple methods of systematic evaluation in narrative analysis for greater validity and deeper meaning. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2019, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mohajan, H.K. Qualitative research methodology in social sciences and related subjects. J. Econ. Dev. Environ. People 2018, 7, 23–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, X.; Ren, H.; Wang, P.; Yang, R.; Luo, L.; Cheng, F. A preliminary study on target 11.4 for UN sustainable development goals. Int. J. Geoherit. Parks 2018, 6, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, O.P. Community involvement for sustainable world heritage sites: The Melaka case. Kajian Malays. J. Malays. Stud. 2017, 35, 59–76. [Google Scholar]

- Roslan, Z.; Ramli, Z.; Shin, C.; Choy, E.A.; Razman, M.R. Local community perception on the importance of cultural-natural heritage protection and conservation: Case study in Jugra, Kuala Langat, Selangor, Malaysia. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2017, 15, 107–110. [Google Scholar]

- Skrede, J.; Hølleland, H. Uses of heritage and beyond: Heritage studies viewed through the lens of critical discourse analysis and critical realism. J. Soc. Archaeol. 2018, 18, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harrison, J.; Laurajane, S. Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology; Smith, C., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dewi, C.; Izziah, H.; Meutia, E.; Nichols, J. Negotiating Authorized Heritage Discourse (AHD) in Banda Aceh after reconstruction. J. Archit. Conserv. 2019, 25, 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, L. Exploring the narrative of heritage through the eyes of the law. Kaji. Malays. 2017, 35, 185–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johar, S.; Che-Ani, A.I.; Tawil, N.M.; Tahir, M.M.; Abdullah, N.; Ahmad, A.G. Key conservation principles of old traditional mosque in Malaysia. WSEAS Trans. Environ. Dev. 2011, 7, 93–102. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, M.J.; Gill, D.J.; Roulet, T.J. Constructing trustworthy historical narratives: Criteria, principles and techniques. Br. J. Manag. 2018, 29, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meretoja, H. The Ethics of Storytelling: Narrative Hermeneutics, History, and the Possible; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Muylaert, C.J.; Sarubbi, V., Jr.; Gallo, P.R.; Neto, M.L.R.; Reis, A.O.A. Narrative interviews: An important resource in qualitative research. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2014, 48, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nasheeda, A.; Abdullah, H.B.; Krauss, S.E.; Ahmed, N.B. Transforming transcripts into stories: A multimethod approach to narrative analysis. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2019, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tuffour, I. A critical overview of interpretative phenomenological analysis: A contemporary qualitative research approach. J. Healthc. Commun. 2017, 2, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, J.H. Narrative data analysis and interpretation: Flirting with data. In Understanding Narrative Inquiry; Kim, J., Ed.; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2016; pp. 185–224. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Method, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, R.; Holland, J. What Is Qualitative Interviewing? 1st ed.; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Roulston, K. Qualitative interviewing and epistemics. Qual. Res. 2018, 18, 322–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, M. Narrative Data. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Collection; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2018; pp. 264–279. [Google Scholar]

- Tversky, B.; Chow, T. Language and culture in visual narratives. Cogn. Semiot. 2017, 10, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daher, M.; Carre, D.; Jaramillo, A.; Olivares, H.; Tomicic, A. Experience and meaning in qualitative research: A conceptual review and a methodological device proposal. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2017, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H. Understanding Narrative Inquiry: The Crafting and Analysis of Stories as Research; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Onwuegbuzie, A.J.; Leech, N.L. Generalization practices in qualitative research: A mixed methods case study. Qual. Quant. 2010, 44, 881–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batch, A.; Elmqvist, N. The interactive visualization gap in initial exploratory data analysis. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2017, 24, 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renz, S.M.; Carrington, J.M.; Badger, T.A. Two strategies for qualitative content analysis: An intramethod approach to triangulation. Qual. Health Res. 2018, 28, 824–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, A.; Chabot, C.; Greyson, D.; Shannon, K.; Duff, P.; Shoveller, J. A narrative analysis of the birth stories of early age mothers. Sociol. Health Illn. 2017, 39, 816–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, D. How was it for you? The Interview Society and the irresistible rise of the (poorly analyzed) interview. Qual. Res. 2017, 17, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, R. The use of composite narratives to present interview findings. Qual. Res. 2019, 19, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, V.; Carvalho, M.; Fernandes-Costa, F.; Mesquita, S.; Soares, J.; Teixeira, F.; Maia, Â. Interview transcription: Conceptual issues, practical guidelines, and challenges. Rev. Enferm. Ref. 2017, 4, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hammersley, M. Transcription of speech. In Handbook of Qualitative Research in Education; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tye, T. At the George Town Waterfront Diorama. 2013. Available online: https://www.penang-traveltips.com/at-the-george-town-waterfrontdiorama.html (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- Khoo, S.N.; Wade, M. Penang Postcard Collection 1899–1930s, 1st ed.; Janus Print & Resources: George Town, Malaysia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cheah, J.S. Penang 500 Early Postcards, 1st ed.; Edition Didier Millet: Singapore, 2012; Available online: http://www.edmbooks.com/Book/1350/6849/Penang-500-Early-Postcards.html (accessed on 13 February 2020).

- Teh, C. The Involvement of the Chinese in Malaysia’s Agriculture Sector. 2012. Available online: http://www.christopherteh.com/blog/2012/01/land-to-till/ (accessed on 12 March 2020).

- Lukauskiene, I. Linen Fabric–Some History. 2012. Available online: http://linenbeauty.com/2012/11/09/linen-fabric-some-history/ (accessed on 4 March 2020).

- Ustavpedia. Linen Fabric. 2017. Available online: https://www.utsavpedia.com/textiles/linen/ (accessed on 4 March 2020).

- Langdon, M. George Town’s Historic Commercial & Civic Precincts, 1st ed.; George Town World Heritage Incorporated: Penang, Malaysia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Islamic Arts Magazine. The Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia (Jan 28–March 28, 2016) Photo Exhibition “The Chulia in Penang”. 2016. Available online: http://islamicartsmagazine.com/magazine/view/the_chulia_in_penang/ (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- Moore, W.K. Malaysian Pictorial History 1400–2004, 3rd ed.; Archipelago Press: Singapore, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, V. Class System in Ancient India. 2012. Available online: https://travelandculture.expertscolumn.com/class-system-ancient-india (accessed on 19 March 2020).

- Social Studies. Ancient India–Caste System. 2013. Available online: http://www.mysocialstudiesteacher.com/wiki/index.php?title=Ancient_India_-_Caste_System (accessed on 19 March 2018).

- Khoo, S.N. The Chulia in Penang: Patronage and Place-Making around the Kapitan Kling Mosque, 1786–1957, 1st ed.; Areca Books: George Town, Malaysia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Travel Picture Gallery. Pictures of Yemen–Traditionally Dressed Men with Their Daggers, Al Mahwit. 2018. Available online: http://www.travelpictures-gallery.com/yemen/yemen-0008.html (accessed on 22 March 2020).

- Bhatt, H. Little India of George Town, 1st ed.; George Town World Heritage Incorporated: George Town, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lubis, A.-R. From “Malay Town” to Acheen Street (Lebuh Acheh). 2010. Available online: http://penangmonthly.com/article.aspx?pageid=9316&name=from_malay_town_to_acheen_street_lebuh_acheh (accessed on 22 March 2020).

- ASERA. Warisan Muslim di George Town, 1st ed.; George Town World Heritage Incorporated: George Town, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Imperial War Museum. Penang Conference on Board Hms Nelson. 28 August to 2 September 1945, on Board the British Battleship Hms Nelson, Flagship. 2018. Available online: https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205161601 (accessed on 25 March 2020).

| Data Coding Used in the Transcription of Informant A and B | Representation of the Data Code |

|---|---|

| Inf A | Informant A |

| Inf B | Informant B |

| Numbering in the middle of the code (1a, 1b, 2, 3, 5a, 5b…) | The sequence of the transcription used in the narrative stories |

| The last numbering of the code (L1, L2…L128) | These codes are used to refer the narrative stories that are extracted from which part of the full/original interview transcriptions. |

| Theme | Aspect | Description | Informants | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | |||

| Garments worn by different ethnic groups in the past life in trading port of Weld Quay | Garments of Ethnic Chinese | Chinese laborers were either kept their body naked or wore mandarin jacket with a matching hat and they would wear long bucket pants at the bottom. | ✓ | ✗ |

| Limited choice of color used to make costume. The main colors of the mandarin jacket were blue, white, and beige, whereas for pants it was wooden brown and black. | ✓ | ✗ | ||

| Garments of Ethnic Malay | Malay-Acheh that showed up in Weld Quay also dressed resembling native Malay. They wore sarung and songkok as well. | ✓ | ✗ | |

| Garments of British | British wore shirt and short pants, which were white in color. Policemen and government officers were both dressed in white. | ✓ | ✗ | |

| Fabric | The fabrics mainly used to make clothes were cotton, silk, and linen. | ✓ | ✗ | |

| Occupational Activities Happened in Weld Quay Trading Port | Chinese Ethnic in Weld Quay | Not all of the Chinese communities worked as stevedores at the port. | ✓ | ✓ |

| The major Chinese communities in Penang were Hokkiens; not many Kwangtung people were found in Penang back then. | ✗ | ✓ | ||

| Chinese communities settled down at the clan jetties were all Hokkiens | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Only Hokkiens from Chew, Lim, Lee, and Ong Jetty would work as stevedores | ✗ | ✓ | ||

| Kwantung people settled down near to the area of Kuan Yin Teng | ✓ | ✗ | ||

| Most of the Kwangtungs worked as tin miner but not stevedores. | ✗ | ✓ | ||

| Indian Ethnic in Weld Quay | Most of the Indian communities worked as stevedores at the port. | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Indian communities were separated in a few types | ✗ | ✓ | ||

| Malay Ethnic in Weld Quay | Native Malays were rarely showed up in Weld Quay’s trading port. They worked as farmers or fisherman. | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Malays who would show up in Weld Quay were Malay-Acheh, as there was a mosque named Lebuh Acheh nearby trading port. | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Malay sub-ethnic groups were grouped as Muslim communities (Jawi Peranakan, Tamil Muslim, Arabic, Hadrami Muslim from Yemen) | ✗ | ✓ | ||

| Some of the Malays from Jawi began setting up printing shops in town. | ✗ | ✓ | ||

| Ethnic British in Weld Quay | Governor or government officer | ✓ | ✗ | |

: The table row that is highlighted with blue represents that the narrative interview data of each aspect was only obtained from one of the informants.

: The table row that is highlighted with blue represents that the narrative interview data of each aspect was only obtained from one of the informants.  : The table row that is highlighted with orange represents that the narrative interview data of each aspect was obtained from both of the informants.

: The table row that is highlighted with orange represents that the narrative interview data of each aspect was obtained from both of the informants.| Statistics of Denotative Element in Visual Data | ||

|---|---|---|

| Data Sources | Inhabitant Garment | Frequency of Visual Used |

| Printed Document | ||

| Postcard | 22 | 51.16% |

| Books | 4 | 9.30% |

| Virtual Outputs | ||

| Website | 5 | 11.62% |

| Archive | 3 | 6.98% |

| Article | 1 | 2.33% |

| Blog | 1 | 2.33% |

| Visit to Penang | ||

| Museum/Gallery | 7 | 16.28% |

| Total Number of Visual Used | 43 | 100% |

| Aspect | Chinese | Indian | Malay | English |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visual Data |  |  |  |  |

| Clothes and the Element | Mandarin jacket elements: designed with four pockets and cloth buttons | Keep the upper body naked or with white shirt (gupha) | Baju Melayu or baju panjang | Suit and shirt in white |

| Pants and the Element | Cropped bucket pants elements: long cloth named (shui mang) used to tighten the waistband area of the pants | White sarong or checkered sarong (kain pelikat) | Chequered sarong or kain pelikat | Pants in white |

| Accessories | Matching with bowler hat or straw hat | Matching with head cloth | Matching with songkok | Matching with white bowler hat |

| Garments for Occupational Activities | Garments with darker or dull color for lower class Chinese who worked as stevedores, laborers, or artisans Suits or mandarin wear in white were for the upper class of Chinese who worked as merchant or government officer. | The garments mentioned above are mostly for lower class Indian ethnic groups mostly found in old Weld Quay who worked as laborers and stevedores. There are different garments for wealthier or higher class Indians such as Hindustanis and Chettiers. | The garments that mentioned at above are dressed by most of the Jawi Peranakan, town Malay, or Acehnese who were working as vendors or traders Malay communities such as Arabic and Hadrami Yemen are different in terms of clothing. | White shirt and had always been the stereotype and a symbol of status for the English who worked as merchants, colonial officers, or governors in the old Weld Quay. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lim, C.K.; Ahmed, M.F.; Mokhtar, M.B.; Tan, K.L.; Idris, M.Z.; Chan, Y.C. Understanding Intangible Culture Heritage Preservation via Analyzing Inhabitants’ Garments of Early 19th Century in Weld Quay, Malaysia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5393. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105393

Lim CK, Ahmed MF, Mokhtar MB, Tan KL, Idris MZ, Chan YC. Understanding Intangible Culture Heritage Preservation via Analyzing Inhabitants’ Garments of Early 19th Century in Weld Quay, Malaysia. Sustainability. 2021; 13(10):5393. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105393

Chicago/Turabian StyleLim, Chen Kim, Minhaz Farid Ahmed, Mazlin Bin Mokhtar, Kian Lam Tan, Muhammad Zaffwan Idris, and Yi Chee Chan. 2021. "Understanding Intangible Culture Heritage Preservation via Analyzing Inhabitants’ Garments of Early 19th Century in Weld Quay, Malaysia" Sustainability 13, no. 10: 5393. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105393

APA StyleLim, C. K., Ahmed, M. F., Mokhtar, M. B., Tan, K. L., Idris, M. Z., & Chan, Y. C. (2021). Understanding Intangible Culture Heritage Preservation via Analyzing Inhabitants’ Garments of Early 19th Century in Weld Quay, Malaysia. Sustainability, 13(10), 5393. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105393