Ambition Meets Reality: Mission-Oriented Innovation Policy as a Driver for Participative Governance

Abstract

1. Introduction

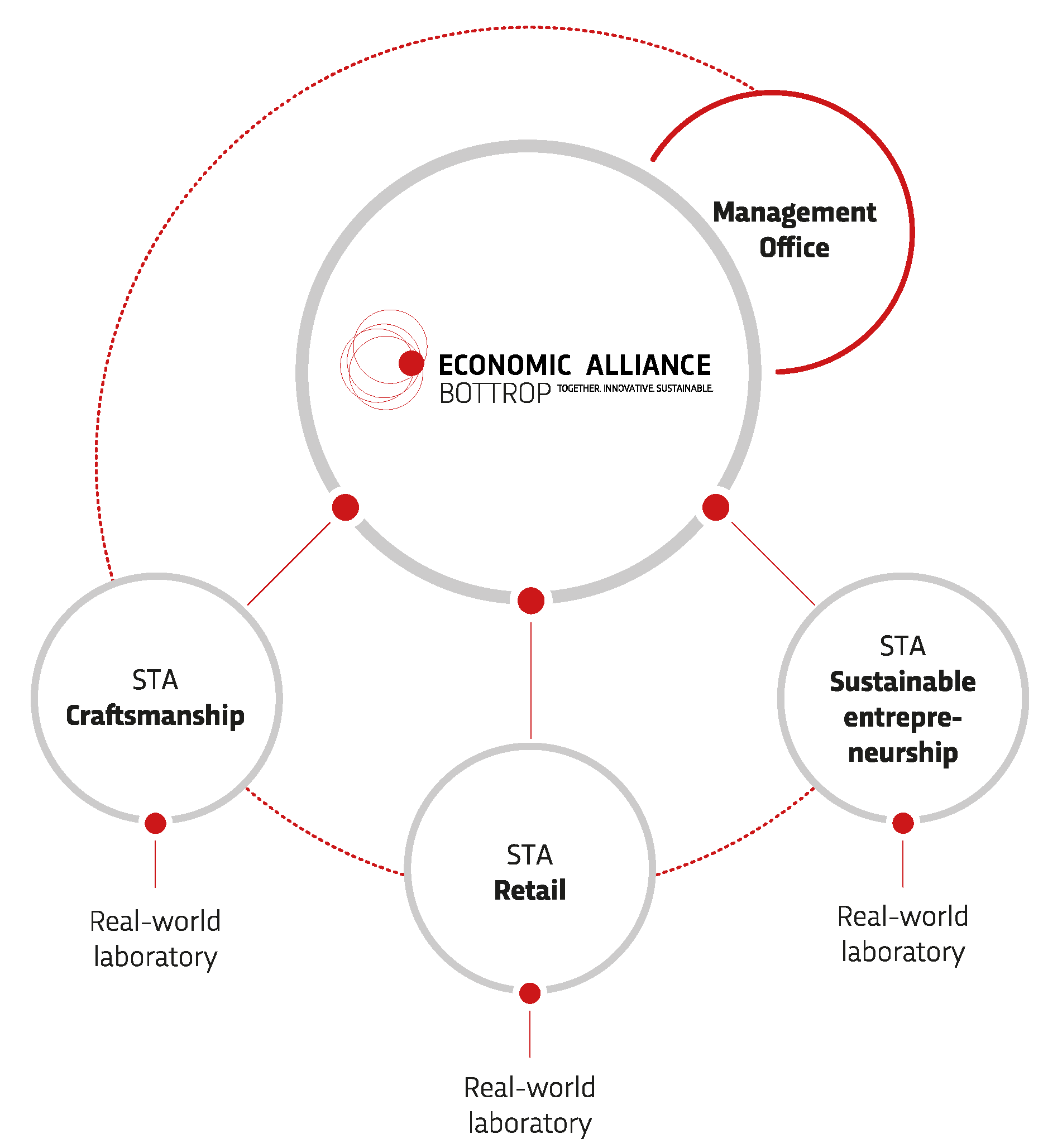

2. Participatory Governance as New Mode of Local Economic Development

2.1. Role of LDAs in Implementing MIP

2.2. (Participatory) Governance

2.3. Transition Management

- Strategic: Defining long-term activities for a shared discussion on the future (e.g., formulating long-term goals).

- Tactical: Determining medium-to long-term activities, which aim at changing established structures, institutions and provisions.

- Operational: Specifying short-term activities (including experiments) to test, implement and demonstrate new ideas, practices and social relations, and

- Reflexive: Activities allowing the collective learning from the dynamics of the present system and the transition processes to the desired future system.

3. Methodology: The Case of Bottrop

3.1. Framework Conditions

3.2. Piloting Participatory Governance: The Experiment Bottrop 2018+

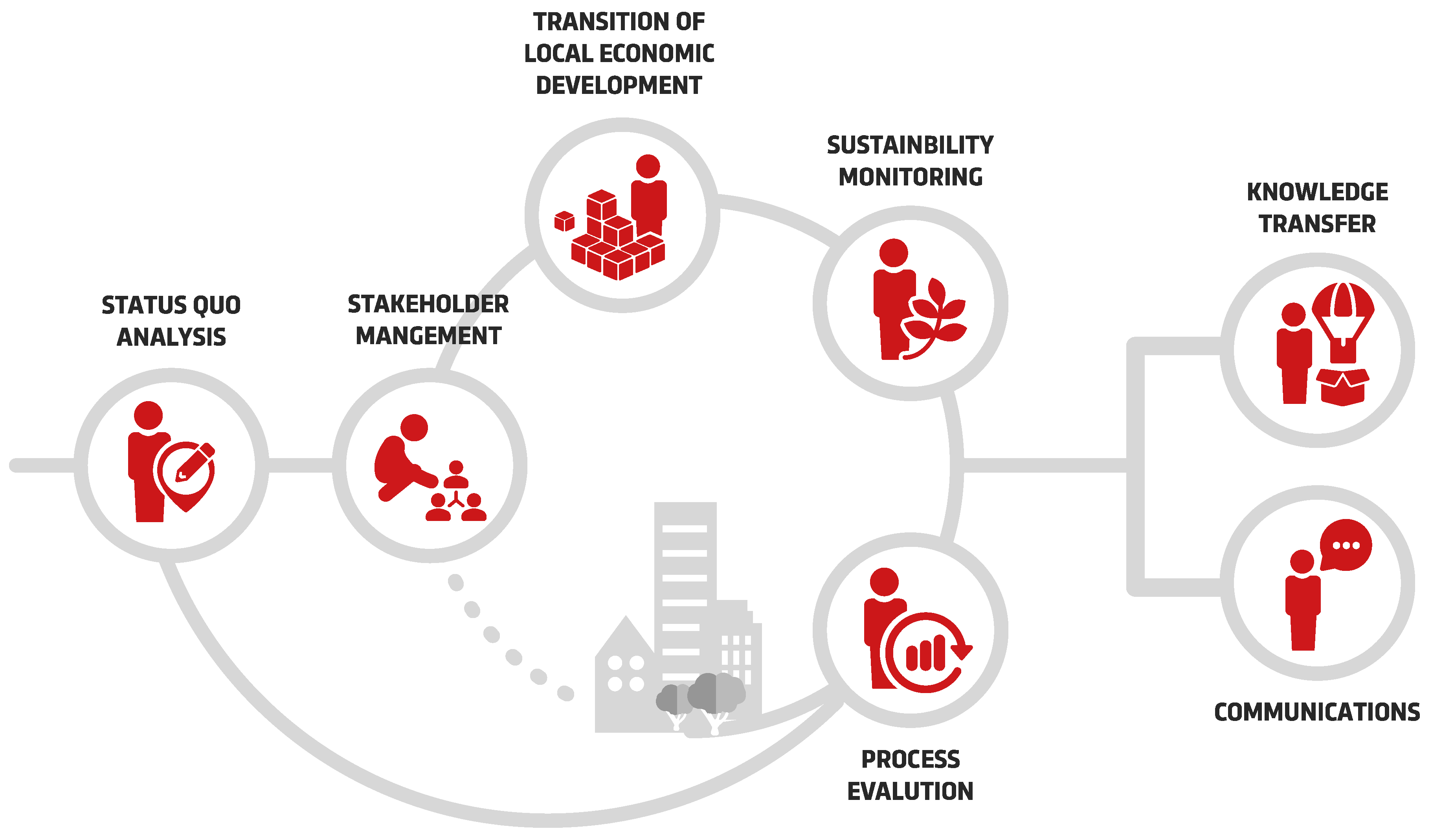

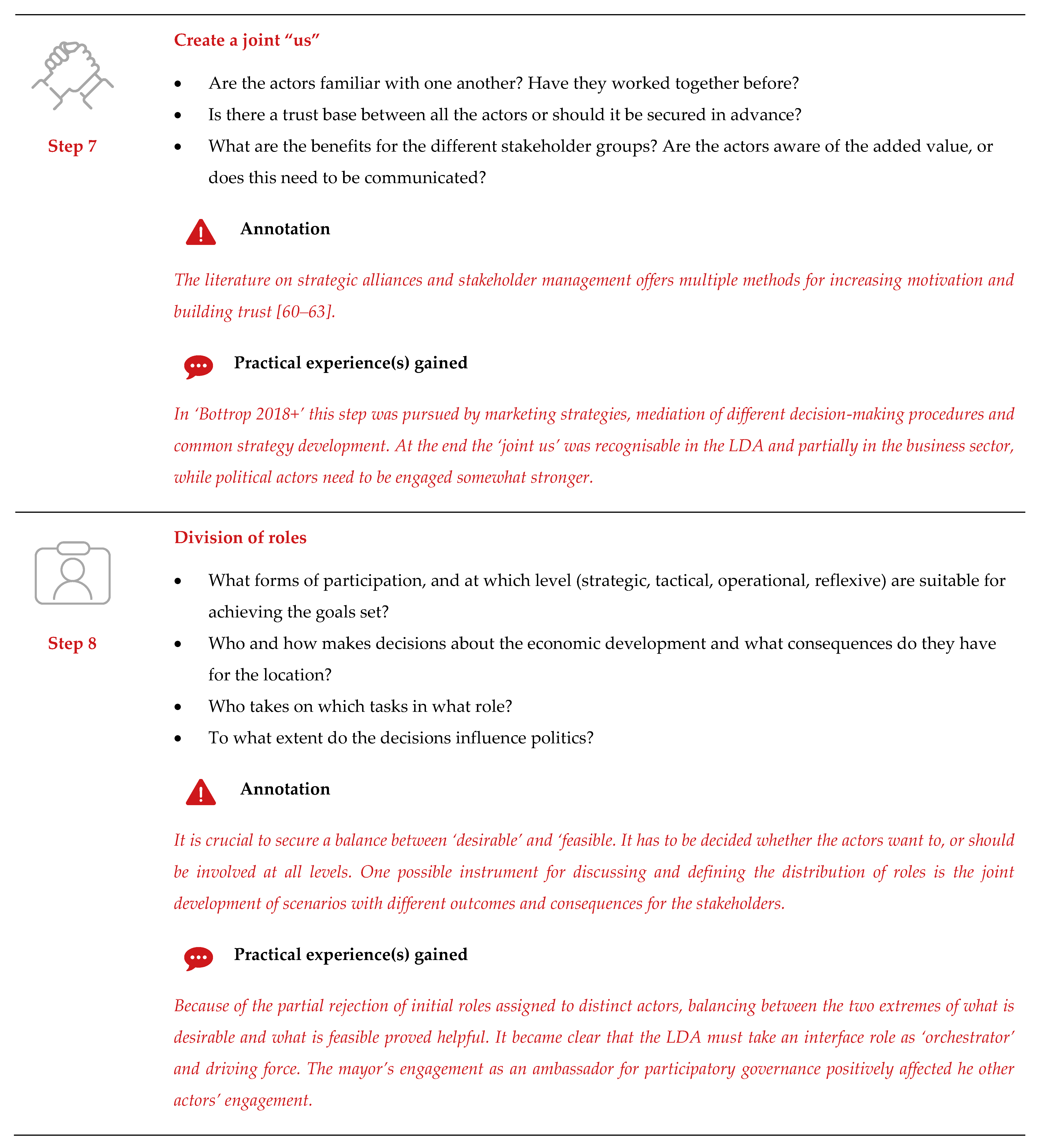

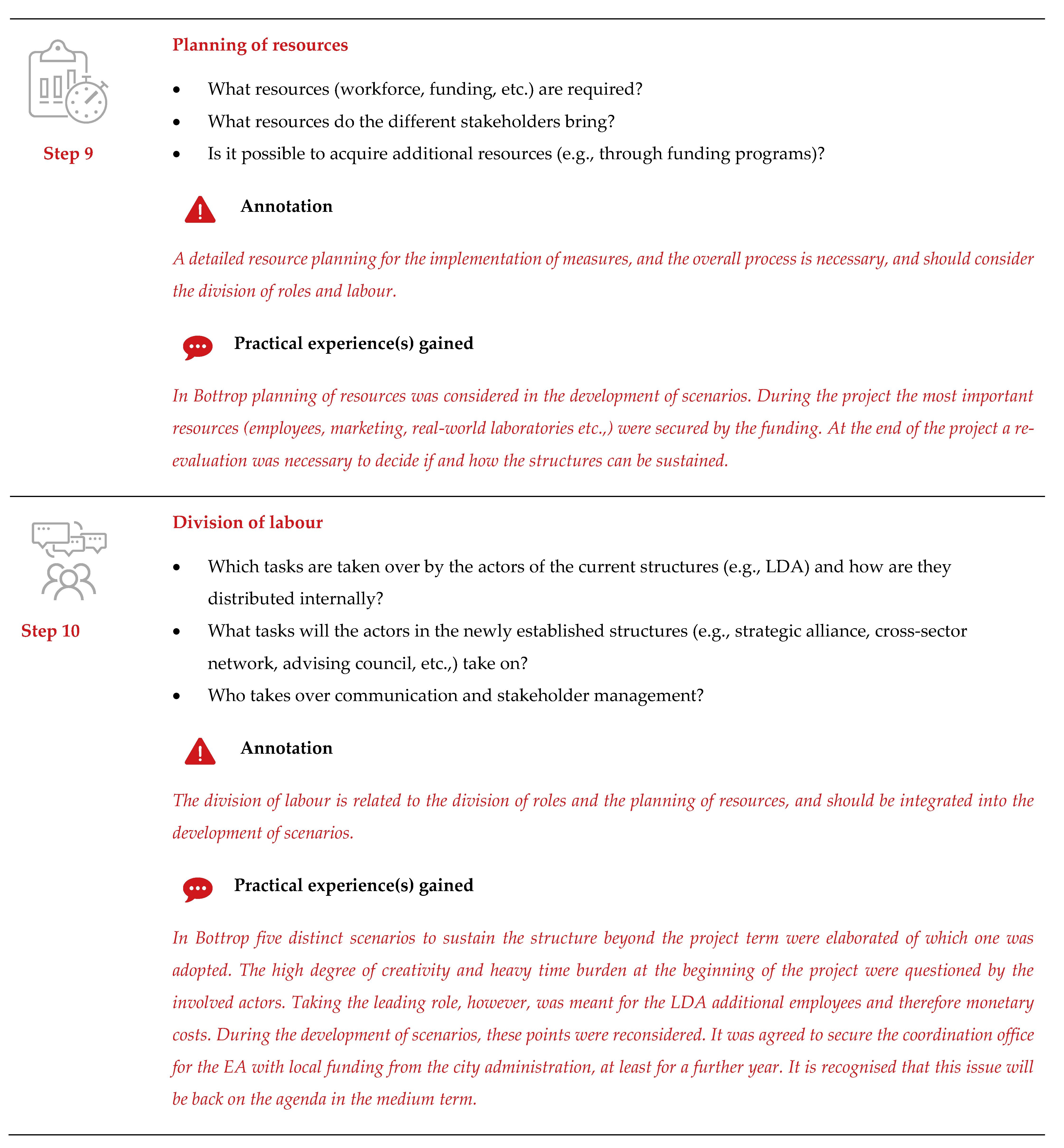

4. Results: Lessons from Practice

- Continuous and effective coordination of activities;

- An interface enabling collaboration between all local actors (politics, administration, intermediaries, economy, and academia);

- Keeping an overview of the sustainability strategy in Bottrop;

- The EA acting as a source of inspiration and driving force.

5. Discussion

- Openness to change: The participatory process requires all actors to reflect critically on their current roles and associated behavioural patterns, and generally be willing to change them. LDAs must dissociate from the mentality of a service provider, and better anticipate future requirements in an everchanging economic environment. Companies have to take more responsibility, not only for their own company and its sustainability, but also for the ‘city’ as a business location, and more generally the urban society. Politicians must have the courage to approach companies and make decisions in dialogue. Only then will the change from reactive to active economic development for the benefit of companies and society, succeed.In Bottrop, this openness was only partially given. While the initial socio-economic and governance analysis revealed the willingness for change, it quickly became apparent that the STA approach is too challenging and that the openness to change requires additional efforts especially as regards firms’ added value (see factor 3).

- Common understanding: A common understanding of the objectives of mission-orientation and its rationale, is necessary. It must be clear what the vision of a ‘sustainable and resilient local economy means, or to be more precise, what is behind sustainability and resilience. Exclusively communicating knowledge derived from theory is not enough, as it remains abstract. Instead, sustainability and resilience must become tangible in everyday life, to give meaning to the multiplicity of local actors with their distinct logics and interests. Thereby enabling actors to take ownership of these terms, will allow to recognise the benefits that come with them, and consider sustainability and resilience as a goal when developing strategies or when implementing measures. That means, however, breaking sustainability and resilience down into concrete problems, and issues of concern for the actor groups involved, in a multilateral dialogue process.Within Bottrop 2018+ project multiple attempts to achieve a better understanding of sustainability and resilience were made. While the actors agreed from the beginning to the common vision, its operationalisation proved challenging. Likewise, the developed and introduced monitoring methodology was disregarded as too complex. Instead, the actors called for illustrating sustainability by good practice and specific business-related examples. Doing so, proved crucial to maintaining actors’ motivation (see factor 3).

- Motivation: Enabling such an intensive dialogue and the joint solution finding, requires a high level of motivation. The actors must recognise their personal, normative or moral benefit of participation, and thus the necessity for active involvement in shaping the local economy to classify a (permanent) commitment as worthwhile. It is essential to elaborate and communicate the specific added value for the various groups of actors, in due consideration of the multiple motives of those involved (e.g., economic or political motives). Closely related to this are problem identification and problem ownership [61]. Actors are motivated to take part in processes and activities if they perceive them as a solution to their problems or challenges. It is essential to actively make the benefits of participation for the different actor groups visible to increase their motivation and long-term commitment.Although a common future structure has been adopted at the end of the project, in Bottrop this task is yet to be implemented. Balancing the ‘desirable’ and the ‘feasible’ emerges as continuous and dynamic negotiation process.

- Trust: It is generally accepted that trust is created through transparency, open communication, reciprocity and repeated interaction. Arguably, ab initio all instruments, mechanisms and processes require openness and clarity on the possibilities and consequences of decisions just as motives for engagement. Results from expert interviews showed that transparency and openness are ensured in Bottrop because of the good (cooperation) work with the LDA and the skills of its employees. However elsewhere, trust-building measures may be required before starting with the participatory processes.

- Avoiding parallel structures: Restructuring economic development, and particularly LDAs, does not mean starting from scratch. Instead, it is vital to begin with what is already there (e.g., existing sector-specific networks). Avoiding parallel structures is of central importance here. When it comes to involving all relevant actors, it is first necessary to clarify what activities and initiatives at a local level the actors are already engaged in, and what the relevant issues are. The aim is not to replace existing networks, but rather to strategically involve and interconnect, and in addition to that, supplement them. Participatory governance is complementary to sector-specific initiatives and aims at cross-sector and cross-structural cooperation. Parallel structures can lead to rejection or resistance to the overall process (‘everything already exists’) or groups of actors withdrawing (‘I have no more time for that’). However, it must be taken into account that not all structures are suitable for achieving the set goals. A re-evaluation of existing structures against the background of sustainability and resilience, is sensible.This factor was proven essential for Bottrop. Precisely against the background that several LDA employees did not feel included and feared replacement of their work by the new structure. It took some effort to clarify the objectives and structural differences, and to reduce resistance and gain support for the idea of participative governance.

- Space for experimentation and reflection: Development and implementation of joint strategies requires space for experimentation and reflection. ‘Space’ is understood here not only as a physical place, but also as freedom and flexibility in the processes and structures. For many actors, participation in governance processes means additional work, and it is essential to create spaces in terms of time and resources. The actors need the freedom to contribute their ideas, but also a certain degree of support in the implementation. Appropriate interface management, networking and funding can help to reduce the risk inherent in the uncertain process.In Bottrop, the experimentation space was secured through the real-world laboratories, which were appraised as a suitable instrument. Nevertheless, the demand for leadership and coordination by the LDA was also expressed in the experimentation rooms. This showed, once again, that breaking away from conventional ways of thinking and doing takes a lot of effort and time.

- Leadership: A participation process also requires leaders to take the management position, function as moderators and bridge-builders and, if necessary, push, set, track and enforce topics. This role can be taken as individual responsibility (e.g., an entrepreneur), or collectively (e.g., LDA). The actor(s) taking this role, on the one hand, have to stand out with their commitment to participatory governance and the underlying mission-orientation, and on the other hand must be broadly accepted by the local actors (e.g., reputation as a reliable partner). In Bottrop, it was not clear from the beginning who would be taking the leadership role. At the end of the project, however, it was communicated that the LDA should take the role. Besides, it must be ensured that the ‘leader’ possesses the necessary capacities, or is supported by acquiring external expertise or additional workforce. For Bottrop, this meant that the management office and the respective position, should be maintained and funded beyond the project term.

- Political commitment: A participatory approach presupposes openness of politics towards new forms of decision-making and planning, to legitimise the new governance structures, and binding nature of the decisions. Next to business, academia, city administration and intermediaries, policymakers are another actor group to be involved in participatory governance, while considering the specific logics and interests (e.g., thinking in electoral circles). Accordingly, policymakers and other political actors should be ‘persuaded’ to participate in the new local economic governance as much as the other actors.The fact that policymakers—with the exception of the major—quickly withdrew from the process and left it for the business sector to shape the EA as a platform for exchange and feedback, underpins the relevance of achieving political commitment. Decisions that entail a political consent were, however, not taken by the EA in the project term.

- Identification and activation of ambassadors: Participatory governance requires supporters, or promoters to ‘push’ the idea of participatory economic development, and to make its benefits known among the local actors. So-called ’ambassadors’, are people who have the potential to contribute to the formation of opinions at the local level, who have a good reputation, who enjoy the trust of local actors and who are perceived as reliable. They need to be identified and activated at an early stage. In Bottrop, the mayor acted as an ambassador and has accompanied and supported the entire process, which proved to be a strong motivator for all local stakeholders to participate.

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

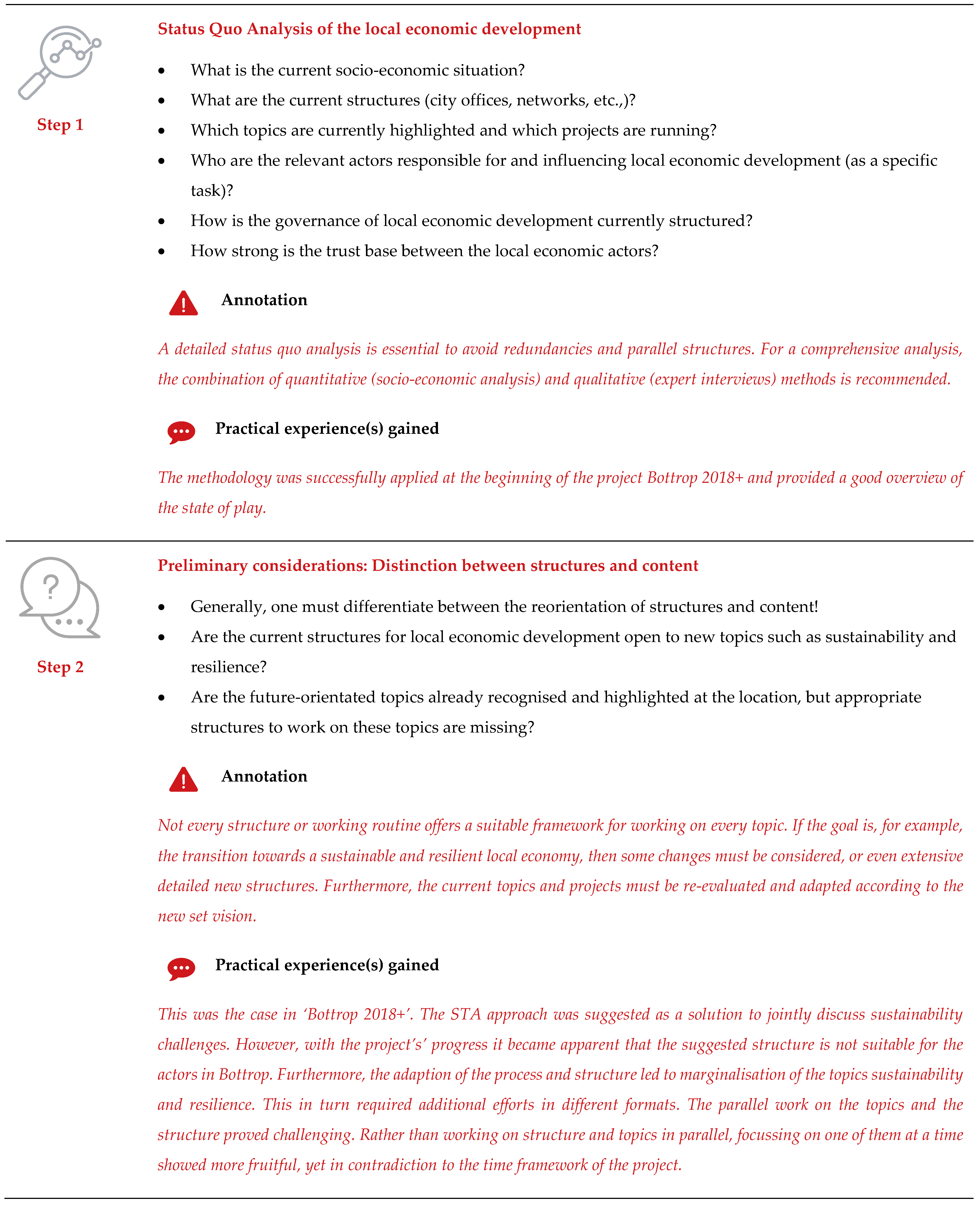

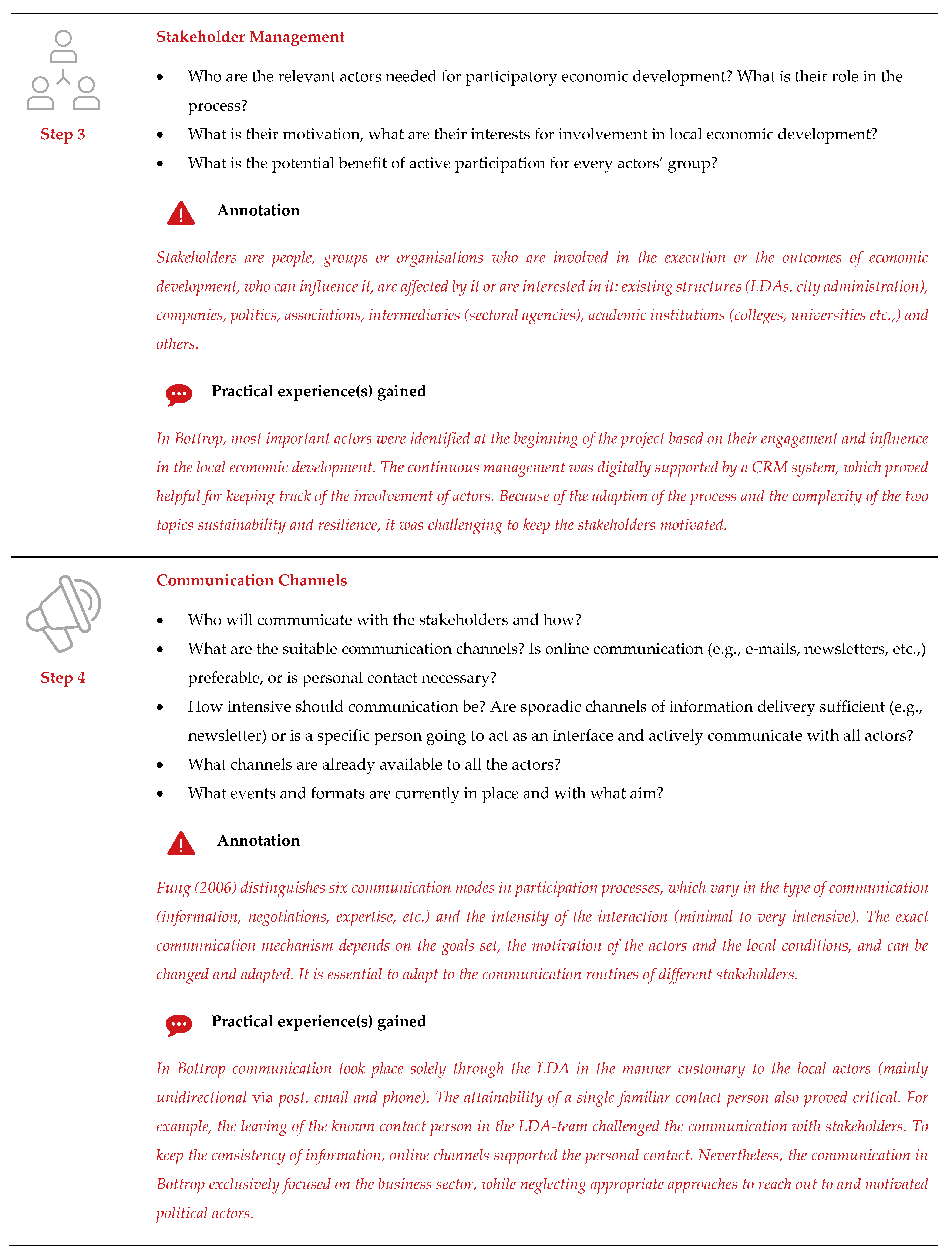

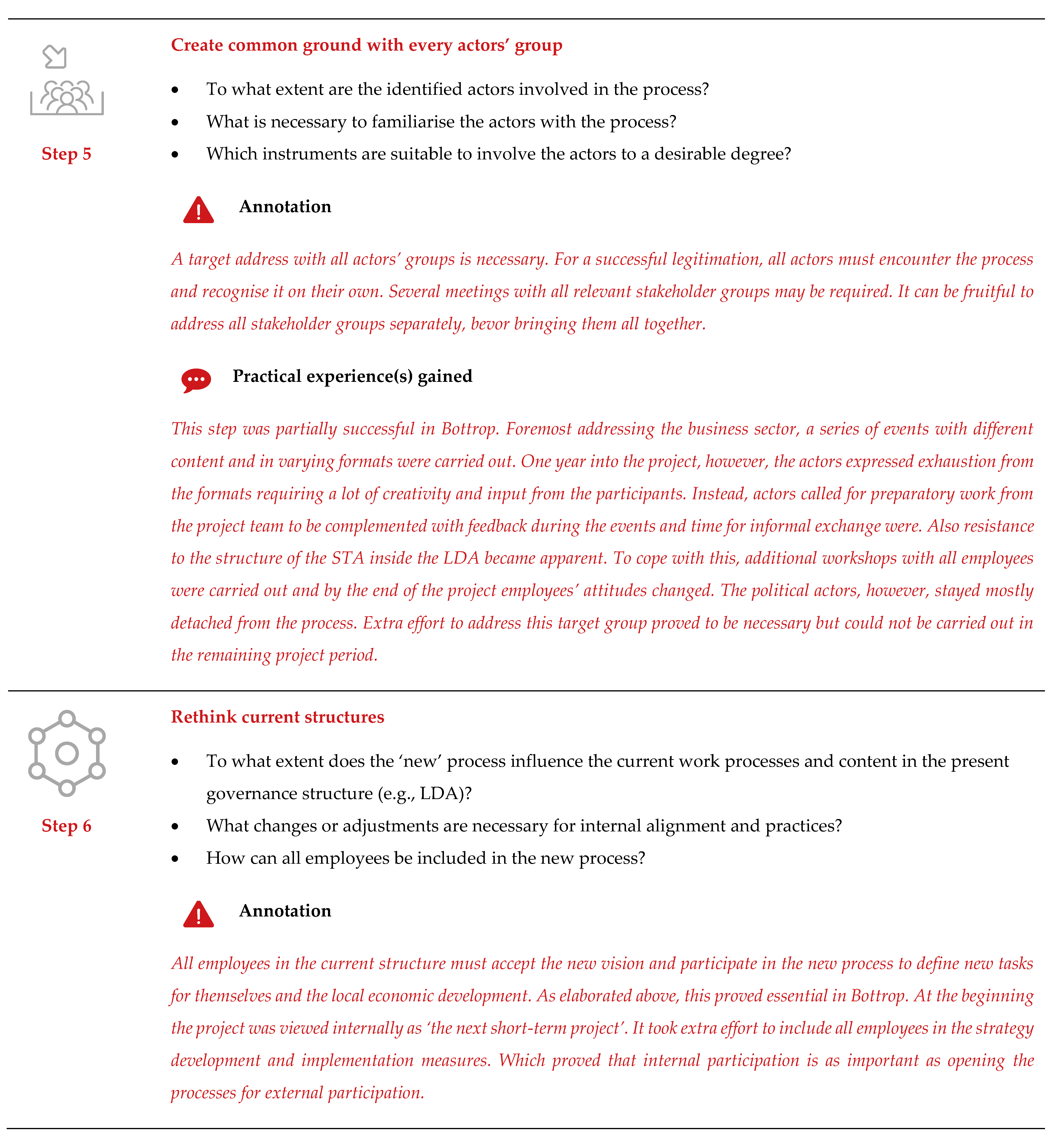

| Tasks | Method | Data and/or Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Status quo analysis: socio-economic situation and governance | Quantitative analysis of data collected official statistics (e.g., DESTATIS, it.nrw, Federal Labour Office) | Population, income, labour market development (unemployment, labour market dynamics, youth and long-term unemployment), school education and vocational training, employment trends and structures, commuter traffic, start-ups, start-up inclination, industrial development, gross added value, enterprises and turnovers, crafts businesses, (environmental protection) investments, tourism |

| Semi-structured interviews with local stakeholders including intermediaries, SWOT analysis, QCA | Perception of the existing governance structures; strength and weaknesses of the local economic development agency; chances and risks for the business location Bottrop | |

| Sustainability Monitoring | Desk research, business survey, secondary data analysis | Indicator set and measurement tool, data on sustainability-related activities of local businesses |

| Communication | The project website, newsletter | |

| Transition of Local Economic Development (LDA) | Balanced scorecard process | Defined vision for sustainable and resilient local economic development translated into operational goals, measures and indicators including the division of work among the involved actors |

| Scenarios | Four scenarios to sustain participatory governance | |

| Semi-structured expert interviews | ||

| Process Evaluation | Expert focus groups | Three annual focus groups with experts from academia, city administration and local economic development; critical reflection on concepts developed and procedures applied |

| Knowledge Transfer | Final conference, networking, conference presentations, articles, integration into teaching | Ten articles, www.strukturwandel.de as a single-entry point for all produced materials, handout »10 Steps towards« (in German only), project booklet, six conference presentations, a final conference |

Appendix B

References

- Foray, D.; Mowery, D.C.; Nelson, R.R. Public R&D and social challenges: What lessons from mission R&D programs? Res. Pol. 2012, 41, 1697–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenken, K. A Complexity theoretic perspective on innovation policy. Complex Innov. Pol. 2017, 3, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzucato, M. From market fixing to market-creating: A new framework for innovation policy. Ind. Innov. 2016, 23, 140–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schot, J.; Steinmueller, W.E. Three frames for innovation policy: R&D, systems of innovation and transformative change. Res. Pol. 2018, 47, 1554–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyarra, E.; Ribeiro, B.; Dale-Clough, L. Exploring the normative turn in regional innovation policy: Responsibility and the quest for public value. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2019, 27, 2359–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diercks, G.; Larsen, H.; Steward, F. Transformative innovation policy: Addressing variety in an emerging policy paradigm. Res. Pol. 2019, 48, 880–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzucato, M.; Kattel, R.; Ryan-Collins, J. Challenge-Driven Innovation Policy: Towards a New Policy Toolkit. J. Ind. Compet. Trade 2019, 20, 421–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanzenböck, I.; Wessling, J.H.; Koen, F.; Hekkert, M.P.; Weber, M. A framework for mission-oriented innovation policy: Alternative pathways through the problem-solving space. Sci. Public Policy 2020, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzucato, M. Mission-oriented innovation policies: Challenges and opportunities. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2018, 27, 803–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hekkert, M.P.; Janssen, M.J.; Wessling, J.H. Mission-oriented innovation systems. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit 2020, 34, 76–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georghiou, L.; Tataj, D.; Celis, J.; Gianni, S.; Pavalkis, D.; Verganti, R.; Renda, A. Mission-oriented Research and Innovation Policy—A RISE Perspective; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrás, S. Domestic capacity to deliver innovative solutions for grand social challenges. In Oxford Handbook on Global Policy and Transnational Administration; Stone, D., Moloney, K., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019; pp. 182–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzucato, M. Missions: Mission-Oriented Research & Innovation in the European Union. In A Problem-Solving Approach to Fuel Innovation-Led Growth; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/horizon-europe-next-research-and-innovation-framework-programme_en#missions-in-horizon-europe (accessed on 28 September 2020).

- Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF). Research and Innovation that Benefit the People. The High-Tech Strategy. BMBF: Berlin, Germany, 2018. Available online: https://www.bmbf.de/upload_filestore/pub/Research_and_innovation_that_benefit_the_people.pdf (accessed on 31 August 2020).

- Linnér, B.-O.; Wibeck, V. Conceptualising variations in societal transformations towards sustainability. Environ. Sci. Pol. 2020, 106, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, B.H.; Holling, C.S.; Carpenter, S.R.; Kinzig, A. Resilience, adaptability and transformability in social–ecological systems. Ecol. Soc. 2004, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C.; Carpenter, S.; Walker, B.; Scheffer, M.; Chapin, T.; Rockström, J. Resilience thinking: Integrating resilience, adaptability and transformability. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, J.; McGregor, J.A. Wellbeing, Resilience and Sustainability. The New Trinity of Governance; Palgrave Pivot: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 39–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.E.; Marshall, N.A.; Jakku, E.; Dowd, A.M.; Howden, S.M.; Mendham, E.; Flemming, A. Informing adaption responses to climate change through theories of transformation. Glob. Environ. Change 2012, 22, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Galloway, W. Understanding Change Through the Lens of Resilience. In Rethinking Resilience, Adaption and Transformation in a Time of Change; Yan, W., Galloway, W., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conen, L.; Hansen, T.; Rekers, J.V. Innovation Policy for Grand Challenges. An Economic Geography Perspective. Geogr. Compass 2015, 9, 483–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M.; Rohracher, H. Legitimizing research, technology and innovation policies for transformative change. Combinging insights form innovation systems and multi-level perspective in a comprehensive ‘failures’ framework. Res. Pol. 2012, 41, 1037–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boon, W.; Edler, J. Demand, challenges and innovation. Making sense of new trends in innovation policy. Sci. Publ. Pol. 2018, 45, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyarra, E.; Zabala-Iturriagagoitia, J.M.; Flanagan, K.; Magro, E. Public procurement, innovation and industrial policy: Rationales, roles, capabilities and implementation. Res. Pol. 2020, 49, 1038–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanzenböck, I.; Frenken, K. The subsidiarity principle in innovation policy for societal challenges. Glob. Trans. 2020, 2, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C. Resilience: The emergence of a perspective for socio-ecological systems analyses. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2006, 16, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagerberg, J.; Huttschenreiter, G. Coping with Societal Challenges: Lessons for Policy Governance. J. Ind. Competition Trade 2020, 20, 279–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattel, R.; Mazzucato, M. Mission-oriented innovation policy and dynamic capabilities in the public sector. Ind. Corp. Change 2018, 27, 787–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogge, K.S.; Pfluger, B.; Geels, F.W. Transformative policy mixes in socio-technical scenarios: The case of low-carbon transition of the German electricity system (2010–2050). Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, F.; Rogge, K.S.; Howlett, M. Policy mixes for sustainable transitions: New approaches and insights through bridging innovation and policy studies. Res. Pol. 2019, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gironés, E.S.; von Est, R.; Verbong, G. The role of policy entrepreneurs in defining directions of innovation policy: A case study of automated driving in the Netherlands. Technol. Forecast Soc. Chang. 2020, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, A.; Doussineua, M. Regional innovation governance and place-based policies: Design, implementation and implications. Reg. Stud. Reg. Sci. 2020, 6, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markert, P. Wirtschaftsförderung und Standortmanagement. In Praxishandbuch City- und Stadtmarketing; Meffert, H., Spinnen, B., Block, J., Eds.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2018; pp. 204–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahner, J. Entwicklung und Regionalökonomie in der Wirtschaftsförderung; Springer Gabler: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welschhoff, J.; Terstriep, J. Wirtschaftsförderung neu denken. Partizipative Governance am Beispiel von Bottrop 2018+. IAT Forsch. Aktuell 2017. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/64608 (accessed on 21 October 2020).

- Rehfeld, D. Auf dem Weg zur integrierten Wirtschaftsforderung: Neue Themen und Herausforderungen. IAT Forsch. Aktuell 2012. Available online: https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:zbw:iatfor:092012 (accessed on 21 October 2020).

- Gärtner, S. Integrierte Wirtschaftsförderung: Regionalökonomische Ansätze und Konzepte. In Wege zu Einer Integrierten Wirtschaftsförderung; Widmaier, B., Beer, D., Gärtner, S., Hamburg, I., Terstriep, J., Eds.; Nomos: Baden-Baden, Germany, 2004; pp. 13–73. ISBN 3832906223. [Google Scholar]

- Lahner, J.; Neubert, F. Einführung in die Wirtschaftsförderung—Grundlagen für die Praxis, 1st ed.; Springer Fachmedien: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.S. The Governance of Urban Regeneration: A Critique of the ‘Governing Without Government’ Thesis. Public Adm. 2002, 8, 301–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrás, S.; Edler, J. Introduction: On governance, systems and change. In The Governance of Socio-Technical Systems, 1st ed.; Borrás, S., Edler, J., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2014; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fürst, D. Steuerung auf Regionaler Ebene versus Regional Governance. Inf. Raumentwickl. 2003, 441–450. Available online: https://www.bbsr.bund.de/BBSR/DE/veroeffentlichungen/izr/2003/Downloads/8_9Fuerst.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=2 (accessed on 21 October 2020).

- Loorbach, D.; Rotmanns, J. The practice of transition management: Examples and lessons from four distinct cases. Futures 2010, 42, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwicker-Schwarm, D. Kommunale Wirtschaftsförderung 2012: Strukturen, Handlungsfelder, Perspektiven; Deutsches Institut für Urbanistik (Difu-Papers): Berlin, Germany, 2013; ISSN 1864-2853. [Google Scholar]

- Jann, W. Governance als Reformstrategie—Vom Wandel und der Bedeutung verwaltungspolitischer Leitbilder. In Governance-Forschung, 2nd ed.; Schuppert, G.F., Ed.; Nomos: Baden-Baden, Germany, 2006; pp. 21–43. ISBN 3-8329-2149-4. [Google Scholar]

- Wiesenthal, H. Gesellschaftssteuerung und Gesellschaftliche Selbststeuerung; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleine, A. Operationalisierung Einer Nachhaltigkeitsstrategie—Ökologie, Ökonomie und Soziales Integrieren; Gabler: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruvis, B.; Mao, Y.; Robinson, D. Three pillars of sustainability: In search of conceptual origins. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerow, S.; Newell, J.P.; Stults, M. Defining urban resilience: A review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 147, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foxon, T.; Hammond, G.P.; Pearson, P.J. Transition pathways for a low carbon energy system in the UK: Assessing the compatibility of large-scale and small-scale options. In Proceedings of the 7th BIEE Academic Conference, Oxford, UK, 24–25 September 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rotmanns, J.; Kemp, R.; van Asselt, M. More evolution than revolution: Transition management in public policy. Foresight 2001, 3, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadowcroft, J. What about the politics? Sustainable development, transition management, and long term energy transitions. Policy Sci. 2009, 42, 323–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loorbach, D.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Huffenreuter, R.L. Transition Management. Tacking Stock of Governance Experimentation. J. Corp. Citizsh. 2015, 58, 48–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittmayer, J.M.; Loorbach, D. Governing Transitions in Cities: Fostering Alternative Ideas, Practices, and Social Relations Through Transition Management, In Governance of Urban Sustainability Transitions; Loorbach, D., Wittmayer, J.M., Shiroyama, H., Fujino, J., Mizuguchi, S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2015; pp. 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, K. Action research and minority problems. J. Soc. Issues 1946, 2, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, D.J.; Levin, M. Introduction to Action Research: Social Research for Social Change, 2nd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2007; ISBN 9781483389370. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsen, J.; Larrea, M. Territorial Development and Action Research: Innovation Through Dialogue; reprint; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsen, J.; Larrea, M. Regional Innovation System as Framework for Co-generation of Policy: An Action Research Approach. In New Avenues for Regional Innovation Systems—Theoretical Advances, Empirical Cases and Policy Lessons; Isaksen, A., Martin, R., Trippl, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 257–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordhause-Janz, J. Sozioökonomische Analyse der Stadt Bottrop. AP1.3 Bericht des Projekts “Bottrop 2018+ Auf dem Weg zu einer nachhaltigen und resilienten Wirtschaftsstruktur.” FONA: Berlin: Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF), Germany. 2017. Available online: http://www.wirtschaftsstrukturen.de/media/2017_nordhause-janz_soziooekonomische_analyse_der_stadt_bottrop.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2020).

- Merten, T.; Bowry, J.; Engelmann, T.; Hafner, S.; Hehn, N.; Miosga, M.; Norck, S.; Reimer, M.; Witte, D. ADMIRe umsetzen—strategische Allianzen zur regionalen Nachhaltigkeitstransformation. Anleitung für strategische Allianzen mit den Schwerpunkten Demografiemanagement, Innovationsfähigkeit und Ressourceneffizienz. Friedberg, Bayreuth, Germany, 2015. Available online: http://f10-institut.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/ADMIRe-umsetzen.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2020).

- Merten, T.; Seipel, N.; Rabadjieva, M.; Terstriep, J. Bottrop 2018+ Auf dem Weg zu einer nachhaltigen und resilienten Wirtschaftsstruktur. In Lokale Wirtschaftsstrukturen Transformieren! Gemeinsam Zukunft Gestalten; Merten, T., Terstriep, J., Seipel, N., Rabadjieva, M., Eds.; Amt für Wirtschaftsförderung und Standortmanagement der Stadt Bottrop: Bottrop, Germany; pp. 18–25. Available online: http://www.wirtschaftsstrukturen.de/media/02_bottrop_2018_-_auf_dem_weg_zu_einer_nachhaltigen_und_resilienten_wirtschaftsstruktur.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2020).

- Engelmann, T.; Merten, T.; Bowery, J. Strategische Allianzen als Instrument zum Management regionaler Transformationsprozesse. In Regionalentwicklung im Zeichen der Großen Transformation; Miosga, M., Hafner, S., Eds.; Oekom: München, Germany, 2014; pp. 349–374. ISBN 3865816894. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, W.H.; Schlosser, R. Success factors of strategic alliances in small and medium-sized enterprises -an empirical survey. Long Range Plan. 2001, 34, 357–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneidewind, U. Urbane Reallabore—Ein Blick in die aktuelle Forschungswerkstatt. pnd|online 2014, 3|2014. Available online: https://epub.wupperinst.org/frontdoor/deliver/index/docId/5706/file/5706_Schneidewind.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2020).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rabadjieva, M.; Terstriep, J. Ambition Meets Reality: Mission-Oriented Innovation Policy as a Driver for Participative Governance. Sustainability 2021, 13, 231. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010231

Rabadjieva M, Terstriep J. Ambition Meets Reality: Mission-Oriented Innovation Policy as a Driver for Participative Governance. Sustainability. 2021; 13(1):231. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010231

Chicago/Turabian StyleRabadjieva, Maria, and Judith Terstriep. 2021. "Ambition Meets Reality: Mission-Oriented Innovation Policy as a Driver for Participative Governance" Sustainability 13, no. 1: 231. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010231

APA StyleRabadjieva, M., & Terstriep, J. (2021). Ambition Meets Reality: Mission-Oriented Innovation Policy as a Driver for Participative Governance. Sustainability, 13(1), 231. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010231