Understanding Communities’ Disaffection to Participate in Tourism in Protected Areas: A Social Representational Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Tourism, Nature and Society

2.1. Nature and the Society

2.2. Tourism Development

3. Theoretical Framework and Prior Analysis

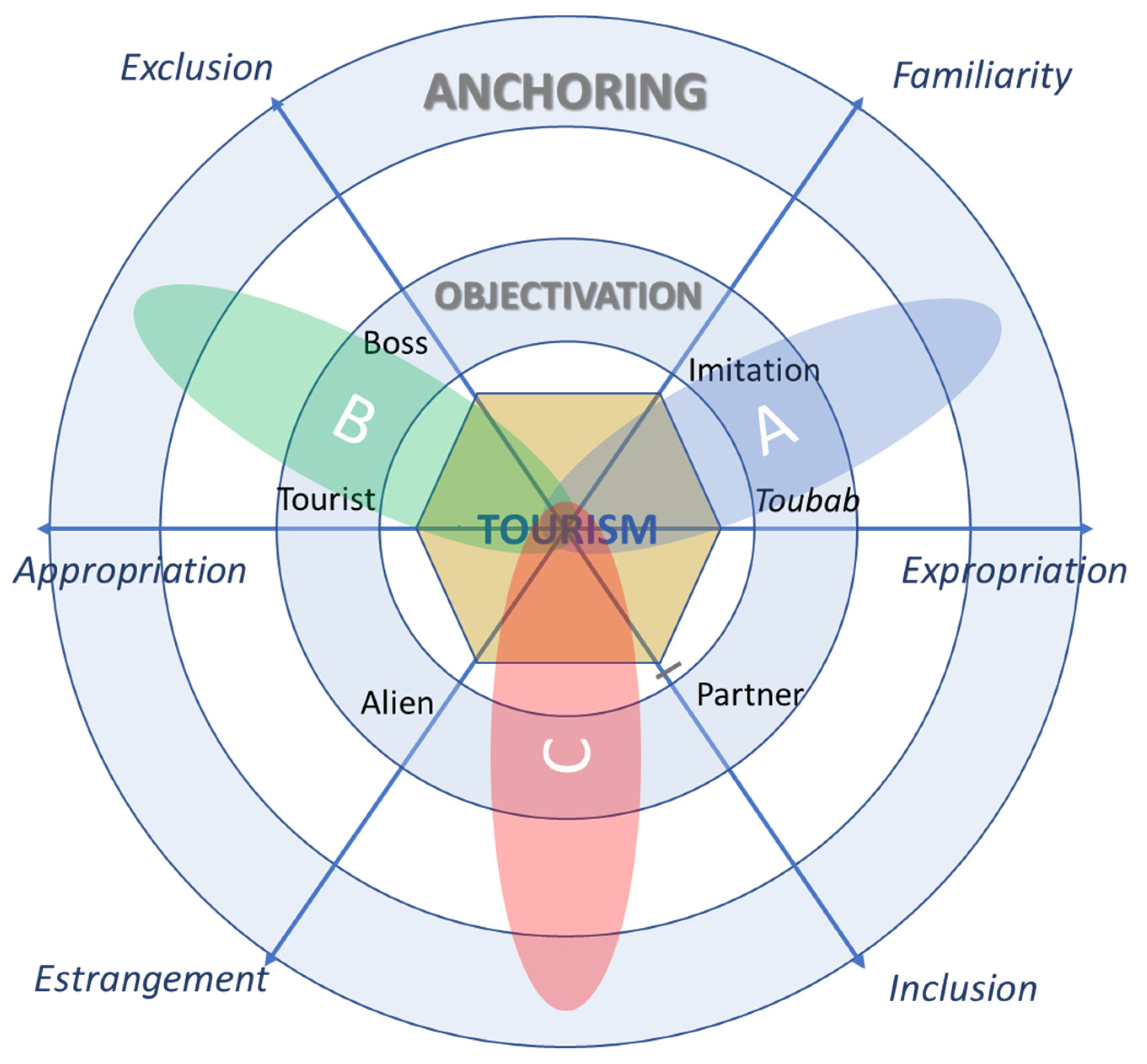

3.1. The Theoretical Framework

3.2. Prior Analysis

3.3. The Model

4. Methodology and Results

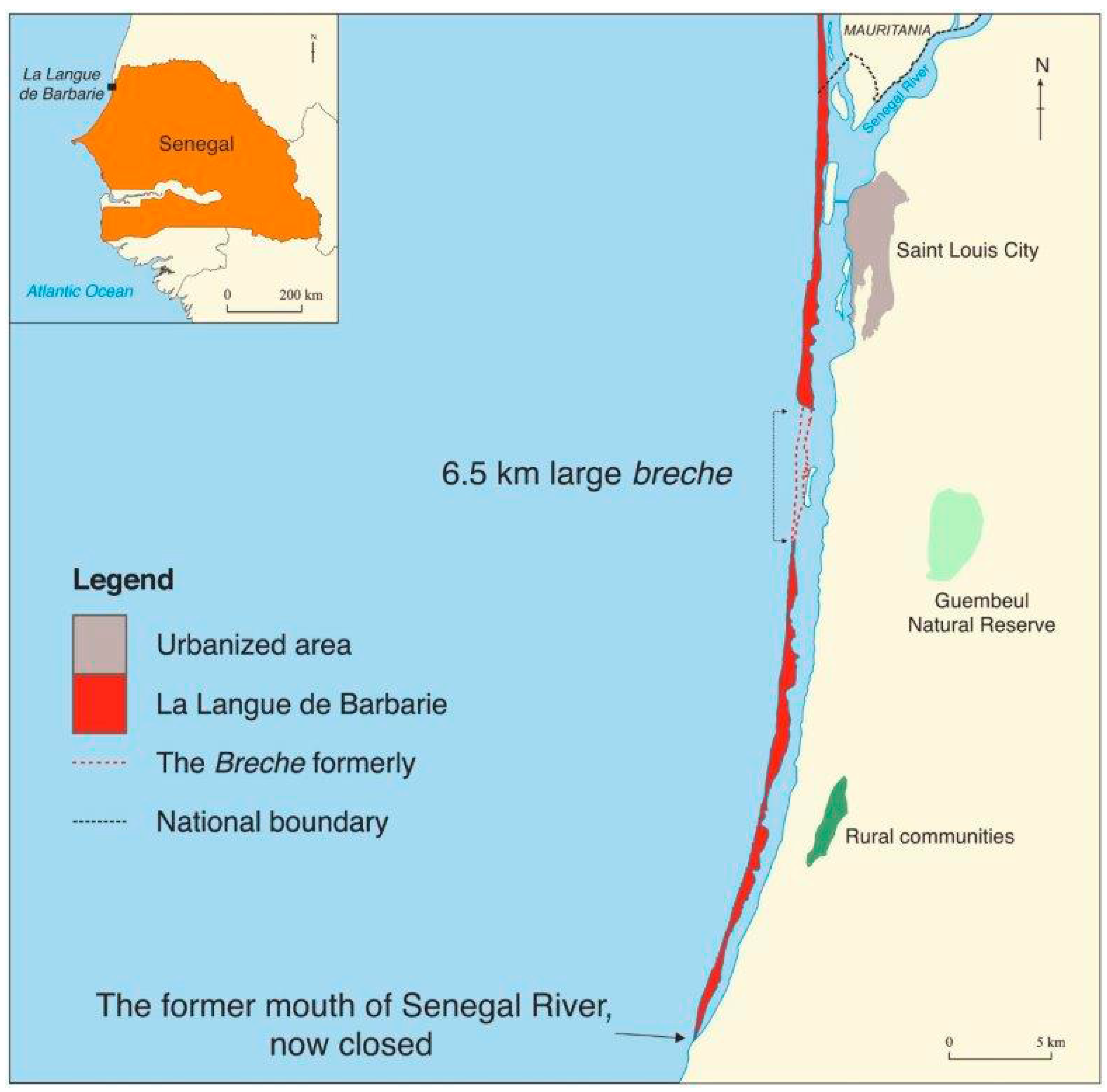

4.1. Data

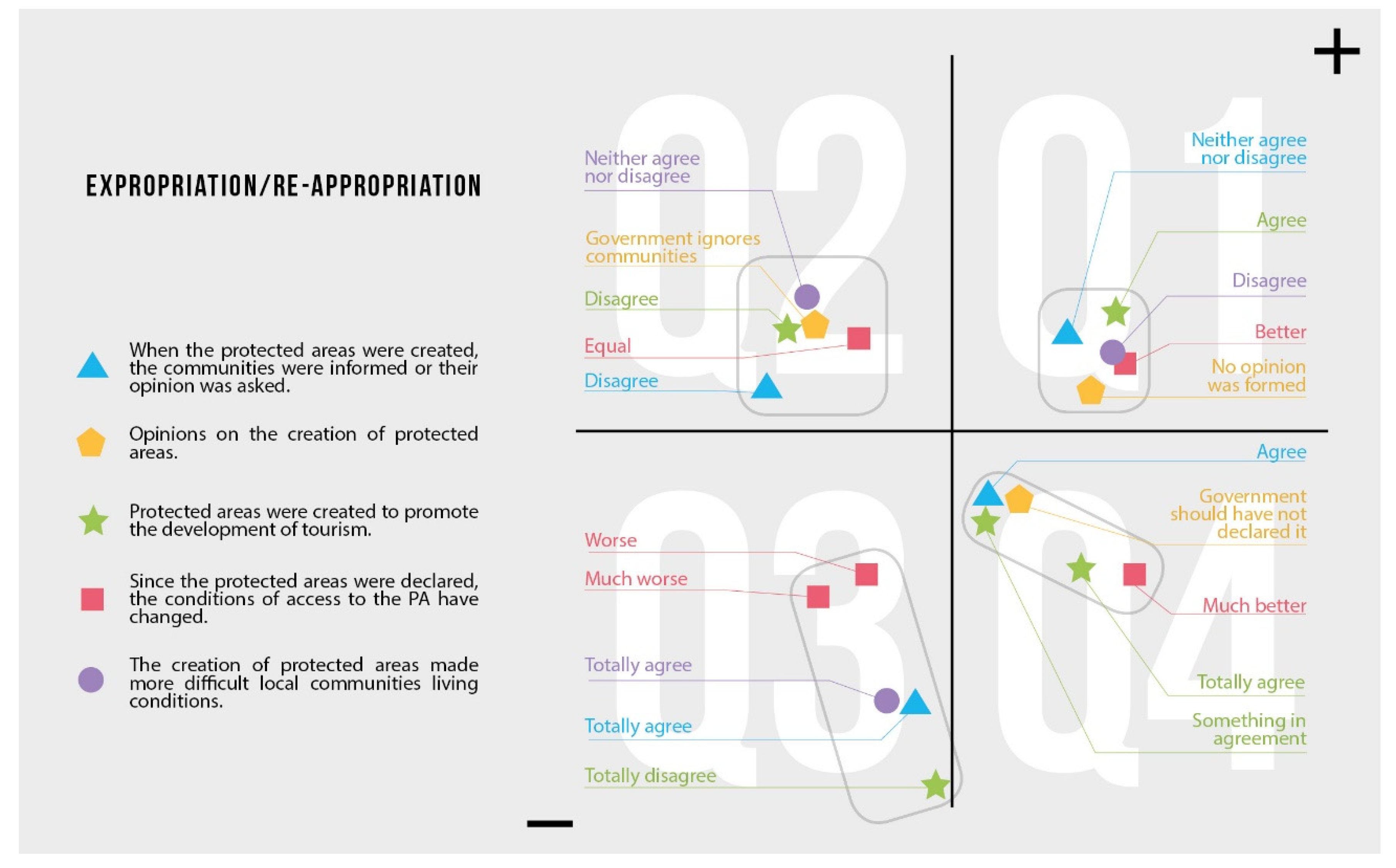

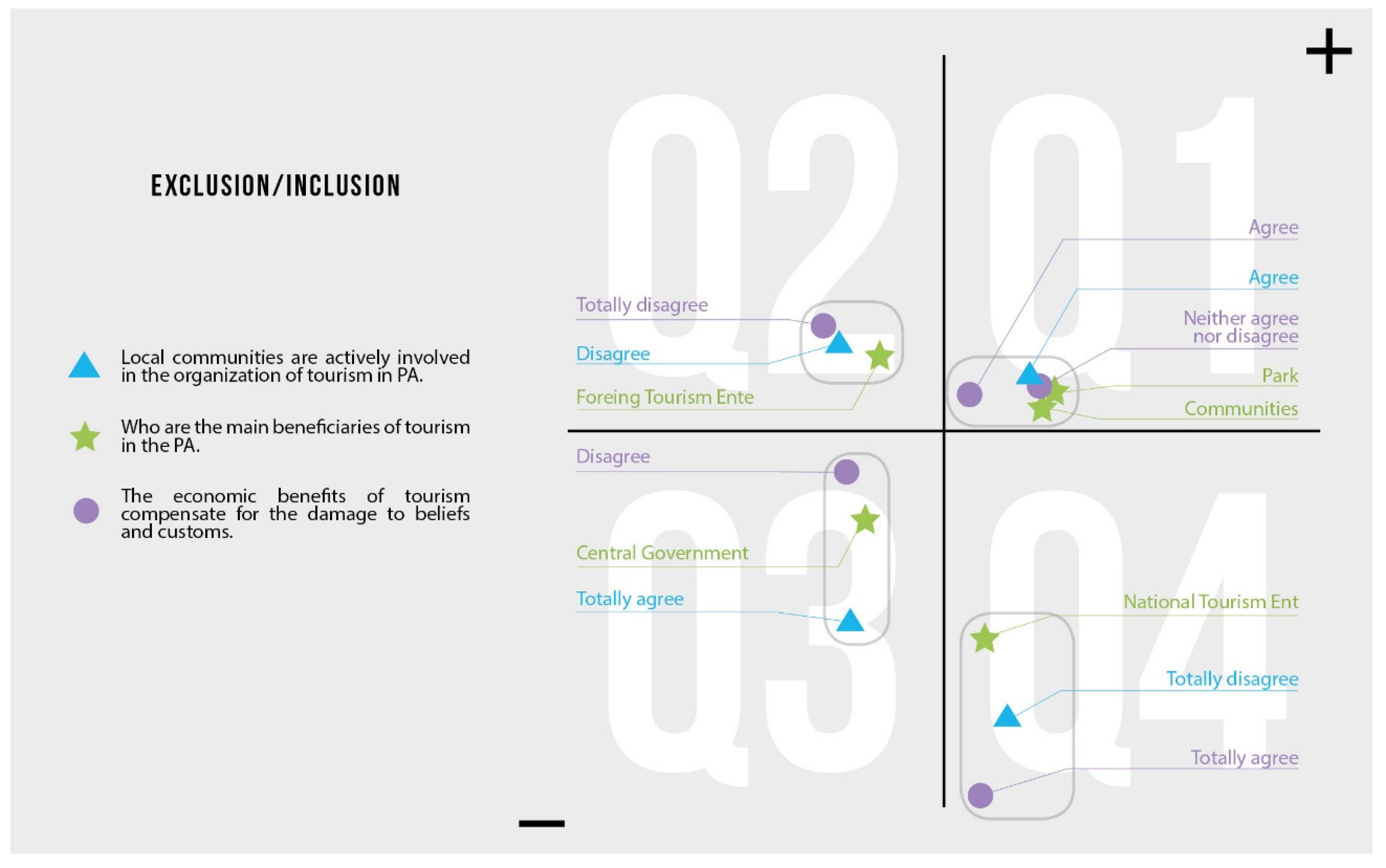

4.2. Questionnaire and Constructs

4.3. Classification of Individuals According to Their Profiles

5. Discussion

6. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Expropriation/Re-Appropriation. Discriminant Measures. | |||

| Variables | Dimensions | Mean | |

| Opinions on the creation of protected areas (Q4) | 0.33 | 0.22 | 0.27 |

| Protected areas were created to promote the development of tourism (Q6-2) | 0.46 | 0.41 | 0.44 |

| Since the declared protected areas, access to natural resources has gone (Q7) | 0.57 | 0.378 | 0.47 |

| When the protected areas were created, the communities were informed or their opinion was asked (Q3) | 0.49 | 0.42 | 0.46 |

| The creation of protected areas made more difficult local communities living conditions (Q5-1) | 0.49 | 0.51 | 0.45 |

| Total | 2.34 | 1.94 | 2.14 |

| Percentage of variance | 54.67 | 45.32 | 50.00 |

| Exclusion/Inclusion. Discriminant Measures. | |||

| Variables | Dimensions | Mean | |

| Economic benefits outweigh harms tourism inflict to our belief and culture (Q29-1) | 0.63 | 0.26 | 0.44 |

| Presently local communities are involved in protected areas’ tourist activities organization (Q11) | 0.59 | 0.62 | 0.60 |

| The first beneficiary from protected areas’ tourist activities incomes (Q12-1) | 0.54 | 0.49 | 0.51 |

| Total | 1.76 | 1.36 | 1.55 |

| Percentage of variance | 58.35 | 45.27 | 51.81 |

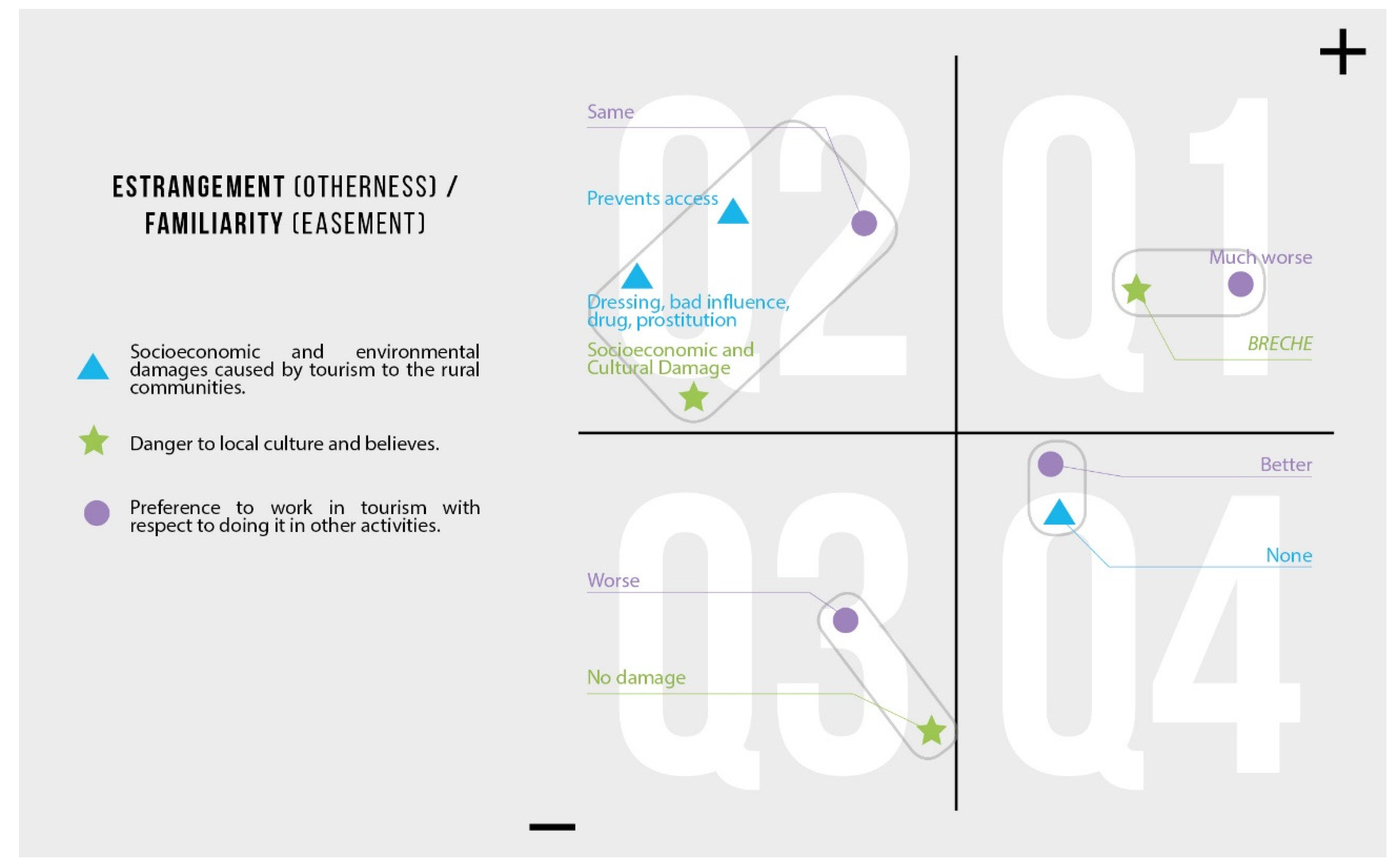

| Estrangement/Familiarity. Discriminant Measures. | |||

| Variables | Dimensions | Mean | |

| What are the first harms tourism do to local communities living near protected areas (Q16-1) | 0.65 | 0.59 | 0.62 |

| Harms tourism is liable to cause to local communities, these first ones exist on the protected areas (Q17-1) | 0.50 | 0.30 | 0.40 |

| Compare working in tourism and working in fishing or agriculture (Q23) | 0.44 | 0.55 | 0.49 |

| Total | 1.59 | 1.43 | 1.51 |

| Percentage of variance | 52.99 | 47.74 | 50.36 |

References

- Hall, D.R. Tourism & Economic Development in Eastern Europe & the Soviet Union; Belhaven Press: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, M.T. Tourism and economic development: A survey. J. Dev. Stud. 1998, 34, 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durbarry, R. Tourism and economic growth: The case of Mauritius. Tour. Econ. 2004, 10, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinboade, O.A.; Braimoh, L.A. International tourism and economic development in South Africa: A Granger causality test. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2010, 12, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzner, M. Tourism and economic development: The beach disease? Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 922–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R. The challenges of economic diversification through tourism: The case of Abu Dhabi. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2002, 4, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarinen, J.; Lenao, M. Integrating tourism to rural development and planning in the developing world. Dev. S. Afr. 2014, 31, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano-Álvarez, F.J.; del Río-Rama, M.D.L.; Álvarez-García, J.; Durán-Sánchez, A. Limitations of Rural Tourism as an Economic Diversification and Regional Development Instrument. The Case Study of the Region of La Vera. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelser, A.; Redelinghuys, N.; Velelo, N. People, Parks and Poverty: Integrated conservation and development initiatives in the Free State Province of South Africa. In Biological Diversity and Sustainable Resources Use; Grillo, O., Venora, G., Eds.; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hulme, D.; Murphree, M. Community conservation as policy: Promise & performance. In African Wildlife & Livelihood; Hulme, D., Murphree, M., Eds.; James Currey: Suffolk, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Naughton-Treves, L.A.; Holland, M.V.; Brandon, K. The role of protected areas in conserving biodiversity and sustaining local livelihoods. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2005, 30, 219–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjalager, M.-A. Agricultural diversification into tourism: Evidence of a European Community development programme. Tour. Manag. 1996, 17, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, D. Ecotourism in the Less Developed World; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, R.; Hall, C.M.; Jenkins, J.M. Tourism and Recreation in Rural Areas; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bushell, R.; Staiff, R.; Conner, N. The role of nature-based tourism in the contribution of protected areas to quality of life in rural and regional communities in Australia. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2002, 9, 24–37. [Google Scholar]

- Binns, T.; Nel, E. Tourism as a local development strategy in South Africa. Geogr. J. 2002, 168, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekhar, N.U. Local people’s attitudes towards conservation and wildlife tourism around Rogerson, C.M. Pro-poor local economic development in South Africa: The role of pro-poor tourism. Local Environ. 2006, 11, 37–60. [Google Scholar]

- Mafunzwaini, A.E.; Hugo, L. Unlocking the rural tourism potential of the Limpopo province of South Africa: Some strategic guidelines. Dev. South. Afr. 2005, 22, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telfer, D.J.; Sharpley, R. Tourism and Development in the Developing World; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mbaiwa, J.E.; Stronza, A.L. The effects of tourism development on rural livelihoods in the Okavango Delta, Botswana. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 635–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, P.; Mukhovi, S.M. Benefits of Protected Areas to Adjacent Communities: The Case of Maasai Mara National Reserve in Kenya. Afr. J. Phys. Sci. 2019, 3, 2313–3317. [Google Scholar]

- Vodouhê, F.G.; Coulibaly, O.; Adégbidi, A.; Sinsin, B. Community perception of biodiversity conservation within protected areas in Benin. For. Policy Econ. 2010, 12, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodhouse, E.; Bedelian, C.; Dawson, N.; Barnes, P. Social impacts of protected areas: Exploring evidence of trade-offs and synergies. In Ecosystem Services and Poverty Alleviation; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sène-Harper, A.; Séye, M. Community-based tourism around national parks in Senegal: The implications of colonial legacies in current management policies. Tour. Plann. Dev. 2019, 16, 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R. Tourism and Poverty; Routledge: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Blake, A.; Arbache, J.S.; Sinclair, M.T.; Teles, V. Tourism and poverty relief. Ann. Tour. Res. 2008, 35, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L.; Forsyth, P.; Spurr, R. Evaluating Tourism’s Economic Effects: New and Old Approaches. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S. A political ecology of water equity and tourism: A case study from Bali. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 1221–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Peeters, P.; Hall, C.M.; Ceron, J.P.; Dubois, G.; Scott, D. Tourism and water use: Supply, demand, and security. An international review. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S.; Morgan, N. Tourism and Inequality: Problems and Prospects; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ashley, C.; Roe, D. Making Tourism Work for the Poor: Strategies and Challenges in Southern Africa. Dev. South. Afr. 2002, 19, 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, H. Reflections on 10 years of pro-poor tourism. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism. Leis. Events 2009, 1, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO (2003). ST-EP Initiative, Sustainable Tourism, Poverty Elimination. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/unwtogad.2003.3.j539023046022q38 (accessed on 15 September 2019).

- Zhao, W.; Ritchie, J.B. Tourism and poverty alleviation: An integrative research framework. Curr. Issues Tour. 2007, 10, 119–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R. Pro-poor tourism: Is there value beyond rhetoric? Tour. Recreat. Res. 2009, 34, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. Pro-Poor Tourism: Who Benefits? Perspectives on Tourism and Poverty Reduction; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Moscardo, G. Exploring social representations of tourism planning: Issues for governance. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, D.; Nelson, F.; Sandbrook, C. Community Management of Natural Resources in Africa: Impacts, Experiences and Future Directions; IIED: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, C.T. Tourism experiences, visitability and heritage resources in Saint Louis, Senegal. J. Herit. Tour. 2018, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, F. Remembering the Nation. The Murid Maggal of Saint-Louis Senegal. Cahiers d’études Africaines 2010, 50, 123–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazar, A. Système de Production et Gestion des Ressources Naturelles Dans la Communauté Rurale de Gandon; Mémoire de DEA Chaire Unesco: Dakar, Senegal, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Direction National des Parcs du Senegal. Rapport Annuel 2018; Ministère de L’environnment et du d‘Veloppement Durable: Dakar, Senegal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ghimire, K.B. Parks and people: Livelihood issues in national parks management in Thailand and Madagascar. Dev. Chang. 1994, 25, 195–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matiku, P. Poverty and mortality indicators: Data for the poverty–conservation debate. Oryx 2008, 42, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepal, S.K.; Weber, K.W. Managing resources and resolving conflicts: National parks and local people. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 1995, 2, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupuy, A.R.; Verschuren, J. Wildlife and parks in Senegal. Oryx 1977, 14, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazar, A. Impacts de la Variabilité Climatique sur Les Écosystèmes des Niayes (Sénégal). Thèse de doctorat, Université Laval. 2009. Available online: http://declique.uqam.ca/upload/files/Memoires_et_theses/Aguiar_2009_these.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2019).

- Michel, P. Les Bassins des Fleuves Sénégal et Gambie; Géomorphol: Strasbourg, France, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Michel, P. Sécheresse, et transformation de la morphodynamique dans la vallée et le delta du Sénégal. Revue de Géomorphologie Dynamique 1985, 34, 113–130. [Google Scholar]

- Cecchi, P. Phytoplancton et Condition du Milieu Dans L’estuaire du Fleuve Sénégal:Effect du Barrage de Diama. Thèse de Doctorat, Université de Montpellier II, Montpellier, France, 1992. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/32974979_Phytoplancton_et_conditions_de_milieu_dans_l’estuaire_du_fleuve_Senegal_effets_du_barrage_de_Diama (accessed on 10 October 2019).

- Camara, M.B. Evaluation d’un Aménagement Littoral: La Pêche et L’ouverture de la Brèche sur la Langue de Barbarie (Grande côte sénégalaise), Impact Écologique et Économique. Dakar, DEA Chaire UNESCO. 2004. Available online: https://catalog.ihsn.org/index.php/citations/46799 (accessed on 5 October 2019).

- Kane, C.; Humbert, J.; Kane, A. Responding to climate variability: The opening of an artificial mouth on the Senegal River. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2013, 13, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosoy, N.; Corbera, E. Payments for ecosystem services as commodity fetishism. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 1228–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, C. Variabilité du Système Socio-Environnement du Domaine Sahélien: L’exemple de L’estuaire du fleuve Sénégal. De la Perception à la Gestion des Risques. Thèse de Doctorat. Thèse de Doctorat, Université de Strasbourg, Strasbourg, French, 2010. Available online: http://www.theses.fr/2010STRA5005 (accessed on 1 November 2019).

- Toure, E.O.; Casals, F.R. El impacto del turismo en la Lengua de Barbarie (delta del río Senegal). Cuad. Tur. 2013, 31, 289–309. [Google Scholar]

- Service Régional du Tourisme de Saint-Louis. Rapport Agence Nationale de la Statistique et de la Démographie, Gouvernement du Sénégal, Sénégal. 2016. Available online: http://www.ansd.sn/ressources/ses/SES-StLouis-2016.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2019).

- Andereck, K.L.; Vogt, C.A. The relationship between residents’ attitudes toward tourism and tourism development options. J. Travel Res. 2000, 39, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurowski, C.; Uysal, M.; Williams, R.D. A Theoretical Analysis of Host Community Resident Reactions to Tourism. J. Travel Res. 1997, 36, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ap, J. Residents’ perceptions on tourism impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 1992, 19, 665–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdue, R.; Long, P.; Allen, L. Rural resident tourism perceptions and attitudes. Ann. Tour. Res. 1987, 14, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Rutherford, D.G. Host attitudes toward tourism: An improved structural model. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skidmore, W. Theoretical Thinking in Sociology; Cambridge University Press: London, UK, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Madrigal, R. Residents’ perceptions and the role of government. Ann. Tour. Res. 1995, 22, 86–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milman, A.; Pizam, A. Social Impact of Tourism on Central Florida. Ann. Tour. Res. 1987, 15, 91–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, C.; Mackens, J.C.; Choy, D.J. The Travel Indus-Try; Van Nostrand Reinhold: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, Y.; Gursoy, D.; Chen, J. Validating a tourism development theory with structural equation modelling. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, D.W.; Stewart, W.P. A structural equation model of residents’ attitudes for tourism development. Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurowski, C.; Gursoy, D. Distance effects on residents’attitudes toward tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 296–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair-Maragh, G.; Gursoy, D.; Vieregge, M. Residents’ perceptions toward tourism development: A factor-cluster approach. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2015, 4, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Smith, S.L.J.; Ramkissoon, H. Residents’ attitudes to tourism: A longitudinal study of 140 articles from 1984 to 2010. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviedo-García, M.A.; Castellanos-Verdugo, M.; Martin-Ruiz, D. Gaining residents’ support for tourism and planning. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2008, 10, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, P.L.; Moscardo, G.; Ross, G.F. Tourism impact and community perception: An equity-social representational perspective. Aust. Psych. 1991, 26, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farr, R. The Roots of Modern Social Psychology, 1872–1954; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Yutyunyong, T.; Scott, N. The integration of social exchange theory and social representations theory: A new perspective on residents’ perception research. In Proceedings of the 18th Annual CAUTHE Conference, Fremantle, Australia, 10–13 February 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fredline, E.; Faulkner, B. Host community reactions: A cluster analysis. Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 763–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriotis, K.; Vaughan, R.D. ‘Urban residents’ attitudes toward tourism development: The case of Crete. J. Travel Res. 2003, 42, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscovici, S. Foreword. In Health and Illness: A Social Psychological Analysis; Herzlich, C., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, W.; Duveen, G.; Farr, R.; Jovchelovitch, S.; Lorenzi-Cioldi, F.; Marková, I.; Rose, D. Theory and method of social representations. Asian J. Soc. Psych. 1999, 2, 95–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srihadi, T.F.; Sukandar, D.; Soehadi, A.W. Segmentation of the tourism market for Jakarta: Classification of foreign visitors’ lifestyle typologies. Tour. Manag. Perspec. 2016, 19, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung-Kun, S.; Kuo-Chien, C.; Yuan-Feng, S. Market Segmentation of International Tourists Based on Motivation to Travel: A Case Study of Taiwan. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 21, 862–882. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida–Santana, A.; Moreno-Gil, S.; Boza-Chirino, J. The paradox of cultural and media convergence. Segmenting the European tourist market by information sources and motivations. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 20, 613–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscovici, S. Social Influence and Social Change; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Moscovici, S. Social influence and conformity. In The handbook of social psychology; Linpzey, G., Aronson, Y.E., Eds.; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Moscovici, S. Silent majorities and loud minorities. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 1991, 14, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscovici, S. Ideas and their development: A dialogue between Serge Moscovici and Ivana Markova. In Social Representations; Moscovici, S., Duveen, G., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Galam, S.; Moscovici, S. Towards a theory of collective phenomena: Consensus and attitude changes in groups. Eur. J. Soc. Psych. 1991, 21, 49–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, E.M. A Ladder of Empowerment. J. Plann. Educ. Res. 1997, 17, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, D.J. Empowerment and Stakeholder Participation in Tourism Destination Communities; Church, A., Coles, T., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Okazaki, E. A Community-Based Tourism Model: Its Conception and Use. J. Sustain. Tour. 2008, 16, 511–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saufi, A.; O’Brien, D.; Wilkins, H. Inhibitors to host community participation in sustainable tourism development in developing countries. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 22, 801–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, F.G.; Lovelock, B.; Carr, N. Constraints of community participation in protected area-based tourism planning: The case of Malawi. J. Ecotour. 2017, 16, 131–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Chiappa, G.; Atzeni, M.; Ghasemi, V. Community-based collaborative tourism planning in islands: A cluster analysis in the context of Costa Smeralda. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 8, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibicho, W. Community-based Tourism: A Factor-Cluster Segmentation Approach. J. Sustain. Tour. 2008, 16, 211–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ven, S. Residents’ participation, perceived impacts, and support for community-based ecotourism in Cambodia: A latent profile analysis. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 21, 836–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D. Residents’ place image: A cluster analysis and its links to place attachment and support for tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1007–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jani, D. Residents’perception of tourism impacts and involvement: A cluster analysis of Kilimanjaro residents, Tanzania. Bus. Manag. Rev. 2018, 20, 60–71. [Google Scholar]

- Rastegar, R. Tourism development and conservation, do local resident attitudes matter? Int. J. Tour. Sci. 2019, 19, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, E.A.; Nadal, J.R. Host community perceptions a cluster analysis. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 925–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani-Farahani, H.; Musa, G. The relationship between Islamic religiosity and residents’ perceptions of socio-cultural impacts of tourism in Iran: Case studies of Sare’in and Masooleh. Tour. Manag. 2012, 4, 802–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.M.; Wu, H.C.; Wang, J.T.M.; Wu, M.R. Community Participation as a mediating factor on residents’ attitudes towards sustainable tourism development and their personal environmentally responsible behaviour. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 1764–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, H.; Santilli, R. Community-based tourism: A success. ICRT Occas. Paper 2009, 11, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, L.S.; Stone, T.M. Community-based tourism enterprises: Challenges and prospects for community participation; Khama Rhino Sanctuary Trust, Botswana. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyman, S.; Bricker, K.S. Living on the edge: Benefit-sharing from protected area tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 705–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S. Information and Empowerment: The Keys to Achieving Sustainable Tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2006, 14, 629–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Village | No of Inhabitants | % |

|---|---|---|

| Ndiebene Gandiol | 4826 | 34.2% |

| Mouit | 2200 | 15.6% |

| Gouyerene | 774 | 5.5% |

| Pilote | 1700 | 12.1% |

| Tassinere | 1363 | 9.7% |

| Ndiol | 499 | 3.5% |

| Degouniaye | 452 | 3.2% |

| Dare Salam | 400 | 2.8% |

| Mbao | 502 | 3.6% |

| Mboumbaye | 1377 | 9.8% |

| Total | 14,093 | 100.0% |

| Expropriation/Re-Appropriation | ||||||

| Variables | Frequencies | % | Frequencies | % | Frequencies | % |

| 1. When the protected areas were created, the communities were informed or their opinion was asked for and taken into account | Disagree or strongly disagree | Neither agree nor disagree | Agree or strongly agree | |||

| 87 | 37.80 | 98 | 42.60 | 45 | 19.50 | |

| 2. Opinions on the creation of protected areas | The government only exercised the competencies it has right to. | The government ignored the voice of the communities | The government should not have declared the protected areas | |||

| 127 | 55.20 | 75 | 32.60 | 28 | 12.10 | |

| 3. Protected areas were mainly created to promote the tourism industry | Disagree or strongly disagree | Neither agree nor disagree | Agree or strongly agree | |||

| 72 | 31.30 | 102 | 44.30 | 56 | 24.30 | |

| 4. Since protected areas were declared, communities’ access to natural resources… | …has got worse or much worse | …has remained equal | Better or much better | |||

| 71 | 30.90 | 73 | 31.70 | 86 | 37.40 | |

| 5. The creation of the protected areas worsened communities living conditions | Agree and absolutely agree | Neither agree nor disagree | Disagree or strongly disagree | |||

| 108 | 46.96 | 42 | 18.26 | 80 | 34.78 | |

| Exclusion/Inclusion | ||||||

| Variables | Frequencies | % | Frequencies | % | Frequencies | % |

| 1. Communities participate actively in the organisation of tourism in the protected areas | Disagree or strongly disagree | Neither agree nor disagree | Agree or strongly agree | |||

| 57 | 24.80 | 86 | 37.40 | 87 | 37.80 | |

| 2. Who are the main beneficiaries of tourism in the protected areas? | Foreign companies and national government | Protected areas and local businesses | The rural communities | |||

| 151 | 65.60 | 64 | 27.90 | 15 | 6.50 | |

| 3. The economic benefits of tourism compensate for the damage to beliefs and customs | Disagree or strongly disagree | Neither agree nor disagree | Agree or strongly agree | |||

| 126 | 54.80 | 86 | 37.40 | 18 | 7.90 | |

| Estrangement (Otherness)/Familiarity | ||||||

| Variables | Frequencies | % | Frequencies | % | Frequencies | % |

| 1. Main socioeconomic, cultural and environmental damages caused by tourism to rural communities | Socioeconomic and cultural damages | Environmental damage (the Breche) | No damage has been caused | |||

| 70 | 30.40 | 102 | 44.30 | 58 | 25.20 | |

| 2. Danger to local culture and believes | Dress, bad influence, drugs, prostitution | Threaten our traditions and lifestyle | No remarkable damage | |||

| 24 | 10.40 | 42 | 18.30 | 164 | 71.30 | |

| 3. Preference to work in tourism with respect to other activities | Work in tourism is worse or much worse | Neither better nor worse | Better or much better | |||

| 140 | 60.90 | 58 | 25.20 | 32 | 13.90 | |

| Constructs | Cluster 1 Reluctant | Cluster 2 Game-Changers | Cluster 3 Escapists |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expropriation | 2.2 | 1.8 | 3.2 |

| Exclusion | 2.6 | 3.0 | 1.4 |

| Estrangement | 1.3 | 3.7 | 2.8 |

| Individuals in each group | 99 (43.1%) | 67 (29.1%) | 64 (27.8%) |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sarr, B.; González-Hernández, M.M.; Boza-Chirino, J.; de León, J. Understanding Communities’ Disaffection to Participate in Tourism in Protected Areas: A Social Representational Approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3677. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093677

Sarr B, González-Hernández MM, Boza-Chirino J, de León J. Understanding Communities’ Disaffection to Participate in Tourism in Protected Areas: A Social Representational Approach. Sustainability. 2020; 12(9):3677. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093677

Chicago/Turabian StyleSarr, Birame, Matías Manuel González-Hernández, Jose Boza-Chirino, and Javier de León. 2020. "Understanding Communities’ Disaffection to Participate in Tourism in Protected Areas: A Social Representational Approach" Sustainability 12, no. 9: 3677. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093677

APA StyleSarr, B., González-Hernández, M. M., Boza-Chirino, J., & de León, J. (2020). Understanding Communities’ Disaffection to Participate in Tourism in Protected Areas: A Social Representational Approach. Sustainability, 12(9), 3677. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093677