1. Introduction

Happiness is a philosophical and sociological concern since the beginning of time, and its research has extended over time to different disciplines. Tourism studies have also become more focused on this and on the general concept of wellbeing in the last few decades [

1]. Happiness is an integral part of the tourist experience [

2]. In recent years, some world measures of happiness have been used and disclosed: The Gross National Happiness (GNH) index of Bhutan [

3] and the World Happiness Report (WHR) by the United Nations (UN) (2019) [

4]; both the index and the report are oriented to gain an understanding of the social perception of both individual and group happiness, and to discover the main identifiable factors related to happiness. We understand happiness in this research as a subjective feeling of wellbeing that could be caused by individual expectancies, beliefs, personality traits and by socio-cultural determinants such as those who are decisive in the perception of the quality of life (QOL) as an emotional concomitant to the overall judgment [

5]. Also, awareness regarding the fragility of the concept is assumed in the sense that there exist a lot of factors (such as religion, moral values, personality, etc.) that affect the self-perception of happiness and also cultural and social elements which determine its nature [

5,

6]. Furthermore, as Max Weber pointed out, [

7] happiness and also happiness perception depends on one’s own ideology, religion and social class [

8].

Recent studies show that tourism development and happiness are positively correlated, but the association between these variables is slim and not exclusive [

9]. Studies that examine whether national happiness attracts more people have shown that international tourists prefer to travel to and spend more time in happier countries; data come from the World Values Surveys in the periods until 2014 matched with tourism data for the corresponding periods [

10]. Also, in relation to the act of recommendation from the visitors to others, the feelings of on-site happiness also predicted recommendation intentions [

11]. The results of the study reveal a close relationship between the level of happiness of the local residents and their perception of the tourism industry and event development [

12]. In a study carried out by Ozturk et al. (2015) [

13], multiple regression analysis indicated that the overall happiness perceived by local residents was significantly influenced by positive and negative cultural and environmental factors, as well as positive economic factors.

Cultural tourism is a current social tendency due to the growing awareness on cultural heritage [

14]; this type of tourism promotes cultural contact, which was found to fully mediate the relationship between visitor engagement and memorable tourism experiences [

15]. There is an increasing interest in cultural tourism all over the world, according to the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) (2018) [

16]. Following this organization and the guidelines based on the work titled ‘Planet Happiness’ [

17], it is possible to identify some of the domains of happiness which are considered and measured in regard to this type of tourism. The main domains measured are community, environment, life-long learning, arts and culture, satisfaction with life, psychological wellbeing, government, health, standard of living—economy, social support, time balance and work. Cultural tourism (especially heritage tourism), both tangible and intangible, are amongst the most vital segments of contemporary tourism. They clearly contributes to the growing popularity of cultural attractions with local communities by raising awareness of the value of their property, while the interest in different aspects of local authenticity enhances reactivation of certain indigenous traditions that have become almost obsolete [

18]. Different studies try to show the intrinsic relationship among tourism, culture, and sustainable development at an international level [

19]. This is one of the main factors supporting the theory of happiness and cultural tourism. Carneiro and Eusebio (2019) [

20] found that the travel group composition, type of tourism destinations, types of social encounters, and overall satisfaction with trips all significantly contribute to the level of influence that tourism has on happiness.

Different studies show that people who feel happy are able to offer their work and commitment, and actively participate in the building of noble things in society [

21,

22]. This underlines that one social and interactive domain of considerable importance in the contemporary world, is tourism (Cohen, 2008) [

23]. It is possible to show how the relationship between tourism development and happiness works through the way in which it shapes the awareness, feelings and emotions of people. Happiness can be considered as an autonomous and subjective feeling with many social influences. Symbolically constructed, it starts at the moment that people have any kind of interaction with others. The important aspects of our lives are all in relation to interaction with others; religion for example, is a very important part of human life [

24]. According to some investigations, tourism development has positive effects on the QOL and happiness of citizens [

25]. Thus, we are taking into account the intense experiences surrounding cultural tourism, as well as the impact it has on the happiness of people in general. Moreover, if we think of different types of cultural tourism nowadays, religious and spiritual ones have a big influence on people’s wellness. The main reason for this is because tourists travel not only for leisure, but also with more serious motives [

26]. Vacations contribute to the wellness and life satisfaction of the majority of people. Therefore, both aspects are important domains of leisure for most people, and are of special and different meaning to individuals at singular points in their life, representing an individual and dynamic concept [

27].

A new spirituality emerges in post-modern societies, and hidden social movements continuously develop. This is very relevant in regard to Luckmann’s perspective, because as he pointed out, religion gives people a moral reference despite levels of individualism, and it is also inherent to the human condition, and consequently to any society [

28]. Nowadays we witness new forms of spirituality that have been emerging since the middle of the last century, counterculture movements and hippies of the fifties and sixties that later merged with the New Age movement [

29]. Here, New Age is understood as contemporary spiritualities of life that are experienced as emanating from the depths of life within the here-and-now, the spirituality of the Holy Spirit and so on. Furthermore, if you take away the God of theism, New Age spiritualities of life remain virtually intact [

30].

In the core of Christianity, we could find emblematic places, mainly holy buildings which have a special atmosphere that promotes introjection and invites to pray and meditate. The point is not exactly oriented towards religion, but to a new spirituality, and even a new religiosity. Such social movements that are in between mysticism and esotericism improve individual and social happiness [

31]. Previous research show the emergence of a new kind of spirituality. Houtmann and Mascini (2002) [

32] say that this “

nonreligiosity”, as well as New Age, are caused by increased levels of moral individualism or individualization. Other authors [

28] explain that current life allows people to have and design individual experiences that respond to their needs and tastes. It is a kind of “à la carte” spirituality or religiosity with a playful aspect. This phenomenon, near the New Age, also reflects the concerns and disagreements of many people regarding the Western lifestyle [

33]. Contemporary modernity gives huge importance to the subjective wellbeing culture; and this culture of subjective wellbeing has played a major role in the growth of inner life spirituality [

30]. Furthermore, New age spirituality is extremely place-specific, and therefore it is manifested in tourism terms with significant enthusiasm regarding pilgrimages [

34].

2. The Holy Grail Route as an Emergent Cultural Tourist Product

The Holy Grail Route is a cultural, tourist, thematic, transnational and European route with the holy cup as its main topic (

www.holygrailroute.eu). A consortium formed by public–private partners and entities from six different countries was formed: Spain, United Kingdom, Bulgaria, France, Greece and Malta are involved in this tourist product. The cultural and business associations have gathered counties, municipalities and interested individuals around the route. A deep social interest and profound emotions emerge around the chalice that remains imperishable despite its very long history and legends and myths that surround it [

31,

35]. Recently, the guardian of the holy cup in the cathedral of Valencia, Dr Jaime Sancho, identified the relic in relation to the tangible heritage of the Christian church [

36], as shown in

Figure 1a. He says that over this sacred relic hundreds of legends, stories and mysteries overlap, providing it with an incalculable wealth.

It is from here where this cultural and spiritual route arises and has synergies with other similar cultural routes that run all over Europe. These paths and roads encourage European heritage to attract people from everywhere, and consequently, some forgotten places are now being endogenously developed [

37], as shown in

Figure 1b. Furthermore, certain organizations, which play an important role as intermediaries between tourists and hosts, have an important influence on both the tourist products and the promotion of sociocultural values of the hosting society.

The significant experience of tourists is supported by a largely unseen network of cultural events, associations and engaged individuals. These different elements together help to produce the ‘atmosphere’ that tourists consume, enjoy and remember [

38]. In Bailo (Huesca), a small Spanish village in La Jacetania in the Pyrinees near France, most people belong to a cultural association called

Asociación Cultural Recreativa de Bailo (ACURBA), and they perform a historical recreation of the arrival and presence of the Holy Grail in Bailo during the 11th century with the “King Sancho III el Mayor”, as shown in

Figure 2a. Another cultural association, Huesca Cuna de San Lorenzo, celebrates an event titled ‘Meeting Places of San Lorenzo and the Holy Grail’, as displayed in

Figure 2b.

There are many populations which were supposedly visited by the cup with which Jesus Christ celebrated the last supper; the physical relic has been nurtured throughout many centuries of legends and stories that, together with the Christian tradition, have left us a cultural legacy that is part of a worldwide collective imaginary. The Holy Grail Route covers an itinerary of thousands of kilometers from Jerusalem to the Iberian Peninsula as shown in Map 1. It enters Spain through Puerto del Palo or Somport and from there, in La Jacetania, it passes through emblematic places such as the Monastery of San Pedro de Siresa, the Abbey of San Fructuoso in Bailo, the Cathedral of Jaca, the Monastery of San Juan de la Peña, the cradle of the Kingdom of Aragon, Yebra de Basa, San Adrián de Sasabe, the Loreto hermitage and San Pedro el Viejo in Huesca, the Aljafería in Zaragoza, Teruel and finally, it arrives into the Cathedral of Valencia. This Basilica is the place where the chalice that the tradition affirms to be the one with which Jesus Christ celebrated his last supper is kept. (See

Figure 3).

The Vatican wanted to reinforce this with the Jubilee Year of Mercy and the Holy Chalice. It was celebrated in 2015 and there will be a jubilee year every five years [

31]. This route passes through different countries and has two main branches. One, based on Arthurian legends, starts in the United Kingdom, crosses through France and arrives in Spain. The other one, related to myths and with a mystical element, goes by the Mediterranean Sea. From a metaphorical perspective, the route is the path that humanity follows to reach the illusion of an eternal life. Thus, people go unconsciously in search of a magic cup whose content contains a mysterious and supernatural power. Faced with such an exploration, there is no doubt that potentially hundreds of people aim their steps towards this route [

35], which is full of emblematic places, historical figures, tangles, unsolved mysteries, a continuous trace of history, and the universal spiritual element that all humans share. The Grail, the object searched for on this route, constantly appears represented in novels, films and even in operas and other artistic fields. The relic is the great symbol of Christianity and furthermore [

36], it incorporates a paradoxical arcane, life and death. This mystery is continuously present in western society, mainly because we are always immersed in different dichotomies of basic emotions. The first encountered myth regarding the Grail was from the times of Chretien de Troyes with his ‘Perceval, the Story of the Grail’ tale (twelfth century), which in current day has a changeable meaning [

39].

The World Health Organization (1990) [

40] highlights spirituality as one of the crucial aspects of social development and individual health promotion. This element gives a sense of life, and improves human happiness through the sense of unity with the universe and by sharing values and beliefs. “Being and duty must be united in the conceived spirituality. ‘Spiritual´ refers to aspects of human life that regard the experiences that transcend sensory phenomena. It is not the same as ‘religious´, although for many people, the spiritual element includes a religious phenomenon” [

41] (p. 2). Following a study made by Ferriss (2002) [

42], in which after reviewing relevant studies and examining data from the 1972–1996 General Social Survey Cumulative File, the main conclusions show that our conception of a ‘good life’ rests heavily upon Judeo–Christian ideals. The doctrine of the religion may attract people of happy disposition. Religion may explain a purpose in life that fosters well-being. Therefore, experiences around a cultural and spiritual route such as the Holy Grail can enhance the sense of life and improve personal happiness.

Paraphrasing Fernando Savater [

43] (p. 10), teaching work has always been approached optimistically and positively. Nowadays, investigation work demands a social commitment of the same approach. The end of every transformative journey is to achieve a dream. We can say that it is the ultimate meaning of life. Nowadays, some cultural routes are oriented to accomplish this goal. On route, the end is to feel that everything changes and nothing remains. It is about the immanence of the walker’s transformation: the one who walks a pilgrimage route is transformed, although the reasons for this transformation may be diverse or even opposed (sacred or secular) [

44]. The metamorphosis reaches unsuspected edges for both kinds of people, and those who began the journey perceiving it as a utopia of change are able to find true happiness. Certain feelings arise in people along the Holy Grail Route that regard illusion, piety and personal motivations of transformation. Such approaches are taken into account by the politicians and technology companies who design and promote this European Route. The social element of the route including a relationship with the local setting is a very important aspect of the tourist product.

In this research, we ask about the relationship between happiness and cultural tourism. This tourist practice is characterized by emotional experiences regarding symbolic topics, emblematic places, representative spaces and landscapes. It also includes some meaningful spiritual and religious experiences coming from certain traditions, activities and products; the Holy Grail Route represents this type of tourist experience.

3. Materials and Methods

To answer the main question in relation to our study, we point out a specific social actor, particularly focusing on the members participating in cultural associations of civil society, and taking into account their deep relation to the tourist product, the Holy Grail Route in Spain. We are able to prove that the people in these social groups represent two important domains of our study: (1) they represent the hosting society, thus they have a specific self-perception of their feelings and opinions towards tourists and visitors; and, on the other hand, (2) they have a deep knowledge of the route, because these organizations are established as a result of it, and thus for this research, they constitute a relevant actor due to their frequent experiences in relation to the tourist product.

There are three main types of these cultural groups along the route: (a) The cultural ones, for example Huesca Cuna de San Lorenzo or UNESCO (Valencia), where members work around the main idea of the Holy Grail and also around the character of St Lawrence who was the protagonist in the traditional story of the Holy Grail in the Christian annals. (b) The historical recreation groups, whose main objective is to generate and spread social interest towards history. These groups are involved in different parts of the route and encourage interest in different moments of the history; some of the representations are in relation to the story of the Grail in Aragon and Valencia, showing different narratives and points of views to ACURBA. Their members come from the small village of Bailo in the province of Huesca (Spain), and they represent an old tradition in which this village relives the arrival of the Holy Grail in the eleventh century. (c) The religious groups, such as the Real Hermandad del Santo Cáliz, that share the main goal of keeping Christian tradition around sacred places in relation to the Holy Chalice. Individuals involved in these groups work from a deep religious belief and at emblematic locations along the route. A qualitative approach was carried out, and the semistructured interviews and information from the participatory process was used to analyze the discourse of the relevant informants.

A sample of twenty-five semistructured interviews was conducted. This sample covered the saturation of the analyzed variables to representatives of the different civil society groups in Spain both in Aragon and Valencia (regions), which are the main territories in relation to the Holy Grail Route. The interviews were conducted during the year 2018 and the first semester of 2019;

Table 1 shows the list of associations in relation to the Holy Grail Route, their location, and the number of people interviewed.

A complimentarily process of participant observation was also conducted during a longer period of time, from 2015 to 2019. According to Bogdan and Taylor (1999) [

45], participant observation is a systematic research process similar to anthropology fieldwork in which the researcher is immersed in the social reality observed. This process takes into account two aspects: (i) the

etic (the researcher perspective) and (ii) the

emic (the perspective of the social actor observed) [

46]. This is a qualitative methodological approach where the situation runs as usual as it would without the presence of the researcher. In our study, this process was completed under a social, cultural, experiential and academic area of work. One of the authors who participated in a cultural association and in an important group of activities gathered all the information and capturing it in a diversity of publications. As a result of this method, the following outcomes were achieved and published: (i) several encounters achieved (San Lorenzo y los lugares del Grial); (ii) an international conference in 2015; (iii) a book about the Holy Grail Route; (iv) a divulgative historical journal; (v) other outcomes such as attendance in meetings regarding the design of the Spanish Holy Grail Route, as shown in

Figure 4 [

31,

35].

The author who was an active participant in one of the cultural associations (Huesca Cuna de San Lorenzo) was also leading the so-called ‘GRAIL project’. Thus, there was an intense participatory work conducted for the sake of complete understanding of the phenomenon. Many of the interviews were carried out within this specific association, and also because these people were involved in the design of the Route since the start. In this paper the research objective is focused on the interviews, but for the analysis, we use the references obtained by the participatory process; mainly because there were occasions in which attitudes, motivations and fears anchored in the past were altered. Grounded theory was applied to the narrative discourse from the interviews and to the references taken from observations (a number of informal conversations and formal meetings).

For the interviews, a script that appears in

Appendix A was used. The questions were oriented in order to answer our main hypothesis: when we observe people in cultural tourist routes that come from very diverse countries, societies and environments and are practically inhabitants from all over the world; automatically, we asked ourselves: can anything be learned from this specific social dynamic that is set in motion in the cultural tourist situation? Is it possible to export behavior patterns to other environments? What are these dynamics? What features do they have? What can be learned from these cultural tourism patterns, if they exist?

4. Results

From the discourse analysis, we discovered relevant categories and concepts which are explained and presented by these results analysis. The main features of respondents appear in

Table 2.

The opinion and perceptions of the interviewees were analyzed, because they are one of the most important hosting actors in the investigated territories; they have a high degree of expertise in relation to the contents along the Holy Grail Route and a deep degree of direct observation of the pilgrims and tourists of this emergent cultural tourist route. Rich information from participant observation was also analyzed following similar criteria.

We developed categories, codes, topics and concepts that are explained. These views mainly came from team work that was in some cases completed with the interviewees; they agreed to collaborate not only by providing their own opinions but also interpreting their own ideas and their judgments regarding the route; specifically, in relation to the three main aspects we discovered along the route and its impact on the individual and socio-cultural happiness, as shown in

Figure 5.

The information obtained has all the obvious ideas, answers and comments surrounding the main variables, but also a lot of hidden narrative lines and arguments. These unknown materials are full of deep contents, and from them, we discovered different aspects of the social dynamics regarding the emergent cultural tourist product. Points of note observed regarding different ideologies and how people use tradition and stories to obtain their own ideological objectives are: the existence of power conflicts within the associations; the story regarding problems of a political nature and the decisio—making in relation to social and cultural issues; and divergences of a personal nature. The agency problem emerges again even in this kind of organization.

Definitively, we discovered interesting factors regarding happiness and happiness perceptions around this emergent cultural tourist product, the so-called the Holy Grail Route.

These three identified dimensions in the narratives of relevant informants in relation to the points described come from the answers to the main items we used in the interviews, and constitute the most important variables in our research:

Structural and psychosocial aspects in the internal dynamics of the groups around cultural tourism affairs;

Relevant environmental concepts;

Cultural tourism and main reasons for happiness.

These three variables are the principal aspects that we have learned from the narratives of people interviewed: first, we discovered a certain degree of social conflict inside the groups; secondly, some environmental aspects emerge in relation to politics, ideology, and networking; and finally, such reasons in relation to our hypothesis and the potential relation between happiness and cultural tourism.

As it is shown, there are some specific points in relation to the topic of concern, such as individual reasons, social cohesion promoted by cultural tourism, the weight of culture in the promotion of individual and social happiness, and finally, how good experiences generate happiness.

In the case of these organizations, it is important to underline that some topics regarding power and leadership emerge, sometimes, as a hidden problem and in other occasions as something obvious. The opinions of the interviewees regarding the main reasons that cause this problem, are:

- (1)

Some of the people involved in the structure are unemployed or underemployed, so they have a lot of time to work and participate in the organization;

- (2)

Other people are retired, so they have also a lot of time to participate;

- (3)

Most of the presidents are the people who founded the structure, so they have a considerable moral obligation to maintain their commitments regarding the structure;

- (4)

All groups consider it a great challenge to participate in the group and to get a publicly and socially distinguished role and recognition;

- (5)

Associations in Spain allow people to receive economic support from public entities, as well as gain social recognition and a private means to develop ideas, projects, etc.

Sharing goals allow people to overcome problems, difficulties and power conflicts; it is also important to recognize that in some occasions, there is a common rational selfishness due to the goals that the group sets up throughout its lifetime. A shared history, mutual intellectual interests, aspirations and motivations give members of the associations an incredible strength to make all the efforts for the association’s survival. This situation is mainly caused as a result of some individuals’ personal motivations in the time of the groups’ foundation and other implicit values which last over time. Specially, in this type of cultural tourism product, it is observed that the deep aspirations of the groups’ members are usually present.

Figure 6 shows the main explanations given by interviewees in relation to their own happiness perception and their opinions on the tourists’ happiness; as it is shown, the causes are quite similar. The improvement of self-esteem thanks to a better understanding of one’s own roots clearly appears as one of the main reasons of individual happiness. Furthermore, another observed explicit factor is the visitors’ impact on the promotion of social relationships, as an increased generation of greater satisfaction among hosting society is provoked. Also, corporal health is improved due to the social dynamics surrounding the tourist route and the physical exercise completed by tourist guides. In general, in the case of a cultural tourist product, both visitors and the hosting society put aside their worries and vital problems, mainly because they are focus on interesting topics. The people of the hosting society can watch other lifestyles and vital situations, and this consequently improves their mental health. Finally, together with this improvement of life conditions, three more reasons were discovered, which are: (a) the sense of self-security, in the way that people feel their general environment is under the desire of other people, so they feel more secure; (b) they are able to establish self-awareness in relation to that; and (c) the development of aspects a spiritual personality.

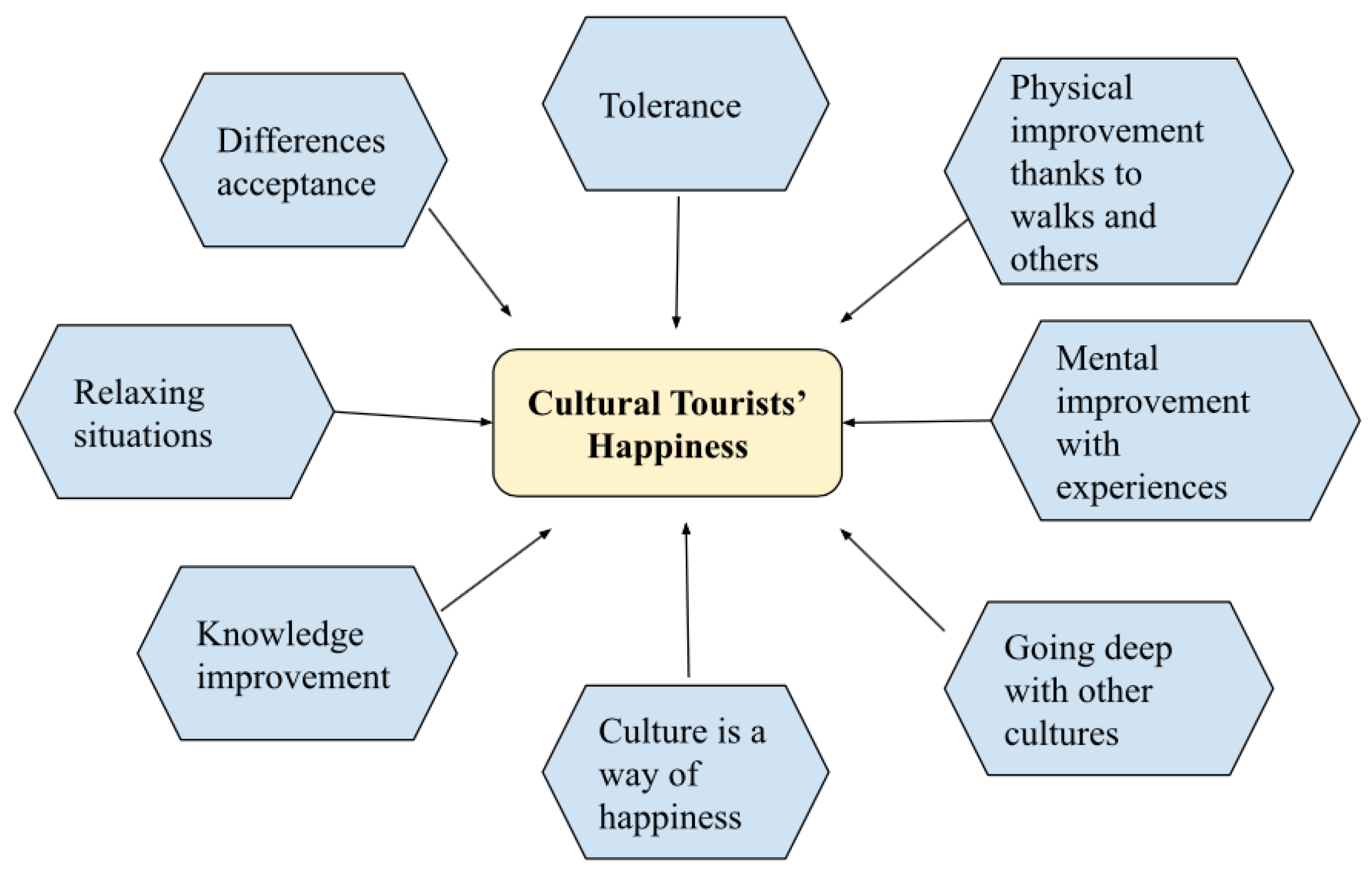

A number of factors impacting cultural tourists’ happiness are present in narratives, and are shown in

Figure 7. From the view of the interviewees, cultural tourism has an impact on the open-mindedness of people, allowing them to become more tolerant. Knowing other civilizations and societies generates positive lived experiences, and visiting different territories influences mental improvement. Active tourism runs together with cultural tourism (more in the specific case of the cultural tourist route) in that some parts can be traveled on foot, by horseback or by bicycle, subsequently improving tourists’ health. Cultural tourism also allows people to deepen their understanding of other cultures, and consequently there is an improvement in knowledge and growth in the level of personal culture. People’s happiness is increased by discovering the world around them in this way. In the Holy Grail Route, there is a spiritual aspect caused by the relaxing experiences lived along it, and a feeling of acceptance of differences is developed. Thus, all these aspects and situations generate a profound sense of happiness among visitors and cultural tourists. Taking into account that all these factors, it can be observed that they are present in the three type of cultural tourists. The first type of tourist travels purely for culture; they are looking to obtain general knowledge and emotional satisfaction around the different cultural stimulus. The second type of tourist want to improve their scientific and historical knowledge. Finally, the third type are those who have a religious conviction and are looking for better understanding of their beliefs. Also, some researchers indicate that travel for pilgrimage, personal growth and nontraditional spiritual practices has been increasing steadily since the 1980s [

44,

48].

Networks developed among all the different structures are observed, and this is an important point which emerges frequently in the research. The density of the networks characterizes the situation of these specific social groups. Links are one of the most important aspects in the relationship of the people inside these organizations. Being a participating member of a certain social group allows individuals experience a sense of belonging. There is a high-density network among members of the groups, but most of the contacts come from informal meetings and encounters. The will to generate formal spaces to promote the Holy Grail Route is very high, but except for the work of five of the associations, the rest of the network comes from random congregations. In the

Figure 8, the basic relations among the groups along the route that were interacted with and observed in our research (to maintain anonymity, names have been replaced with letters) are shown. Five of them have quite fluent contact and communications, but the others interact more sporadically.

Nevertheless, in addition to the network density, a territorial aspect appears repeatedly in the narratives. Most of the organizations have an intense relationship with their own locations, in the sense that they are conducting activities, performances, meetings and exhibitions with people and entities in the geographic territory to which they belong. Thus, their events and actions have an impact on the society nearest to them. This special circumstance emerges because the civil social movement’s sense of existence is in its relationship with culture, tradition, legend and history. These associations have an important social role in relation to keeping characters such as Saint Lawrence alive in Huesca, maintaining interest in iconic and emblematic places such as San Juan de la Peña and the Cathedral of Jaca in La Jacetania, generating attraction towards tangible cultural heritage such as the Holy Chalice in the Cathedral of Valencia, and finally, maintaining and guarding other intangible inheritance such as all the legends, stories and tales that give to the territory an authentic sense and unique feeling. Thus, these cultural groups express their desire and need to be useful and to be of service to their regions and people around them. They also have a deep responsibility to make all the heritage and authenticity of their regions known to the world.

In interviews, relevant informants were asked to give opinions on and rate the items of a Decalogue showing the relation between cultural tourism and individual and social happiness. This was built by the authors with knowledge from a documentary analysis regarding the research topic. The Decalogue was then given to interviewees to score items from one to ten, where one was the minimum agreement and ten was the maximum. The items are based on the main reasons for life satisfaction and happiness in the cultural tourism experience, coming from own tourist experiences. The developed items of proposals could be applied to other environments to generate harmonious coexistence, balance and social sense, as well as peaceful social encounters and meetings.

As can be seen in

Table 3, the most relevant item in the Decalogue is the second one: “Away from stress, competitiveness, monitored time. Cultural tourism places us in a nonzero-sum mode: we all win”. It seems that during these kinds of experiences, people completely escape the competitive world, and an integral and different sensation invades personal life. This specific experience means that social life is perceived in a different manner, and people are surrounded by an atmosphere of well-being.

In the first item—“Experience the present with intensity, recovering experiences of a historical nature, all of which motivates individual well-being”—we can discover one of the Buddhist reasons for happiness: the awareness of being here and now and the sense of compassion in life [

49]. What does it mean? If people are able to live in the present moment, their stress levels decrease because they no longer long for a better past, nor do they focus on the uncertainty of the future to come. Thus, happiness arises quickly. Nevertheless, to gain this level of awareness is not so easy, most of the gurus who work in self-help consider it necessary to carry out continuous training in order to achieve this state of well-being. However, certain specific experiences, such as those experienced in cultural tourism, can cause feelings of well-being of this type.

The following items in the rank are nine and ten: “Development of participatory observation capacity with distance and respect”, and “Acceptance of experiences even in adverse circumstances, if they emerge. For example: climatic and environmental adversities, provision of services, food, etc.”, respectively. We can consider that the first item is the origin of any society, because it is based on sharing behaviors and respect for others. In the second item, acceptance is the key; in Buddhist practice, acceptance means adaptation and resilience as opposed to conformism. From this philosophical tradition, happiness is based on acceptance and it is easy to understand how cultural tourism experiences stimulate acceptance.

The other three items in the rank are: “Environmental commitment and human engagement”, “Development of high levels of tolerance in relation to elements that are set in motion, such as time, services, noise, tastes of others, etc.” and “Tendency to the absence of religious modes. They are all the same: closeness to spirituality”. These three items display two of the main aspects of sustainability: the environmental and the socio-cultural factors, in the sense that if all these items are really generated by cultural tourism, then sustainability should be possible. Finally, the sixth item: “Absolute deideologization, a quasi-apolitical situation is generated”, is one of the most difficult points because for some people this is not important, but for others it is considered very important. Nowadays, it is difficult to generate and find situations in which a political discourse is not present or in which ideology is objective, and accessing the true essence of things, as seen in the narratives, is a significant challenge.

5. Discussion

As Smith and Dikemann (2017) [

1] confirmed in their study, we discovered through the obtained opinions of members from civil society associations, that cultural tourism enhances happiness in both the hosting society and the visitors. These authors also show, as in our results, that well-being-enhancing tourism is based on a hedonic and

eudaimonic spectrum. This means that in one way, we need to experience some pleasure to gain well-being, but at the same time, we also have to feel that our life has a meaning and get pleasure through good experiences, such as those which improve social commitment or those which improve knowledge and culture. In the cited research, the authors argue that increasing investigation has evidenced that tourism is beneficial for mental and physical well-being, which is in complete accordance with our results. Furthermore, the visitors’ impact on the promotion of social relationships in the place they visit generates greater satisfaction among members of the hosting society. Due to the social dynamics, the physical health also improves; people are away from their concerns of daily life and they can watch other lifestyles and situations. It is also important to realize that some types of tourism are better than others. Thus, some travel companies combine their products and packages in such way that tourists are able to enjoy an evocative and cultural experience that also has hedonic elements and opportunities for relaxation. Like the discoveries of Smith and Dikemann (2017) [

1], our research also proves that all forms of tourism, especially the cultural one in its extended form, can contribute to improving the quality of life of tourists and hosts. This is mainly because traveling allows people to take advantage of free time and the positive consequences (relaxing, slow practices, time for thinking, etc.) that follow as a result. In addition, the social dynamics around this tourist experience helps to improve the self-esteem of the hosts in that it allows them to perceive the natural and socio-cultural resources that they own.

In our study, one of the main reasons for individual happiness is in relation to the improvement of self-esteem due to a better understanding of their own roots. Similar results were discovered by Butkovic et al. (2019) [

50]. Self-esteem is an important predictor of life satisfaction at different stages of life, identifying life satisfaction with happiness in a broad sense. Also, as with our results, some authors highlight that experience economy is higher in cultural tourism practices since culture’s intrinsic values are inherently linked to them [

51]. We saw not only positive social dynamics in these social structures related to the cultural route, but also problems which characterize these kinds of collective organizations. Accordingly, other types of problems were observed, such as group decisions being made by particular individuals and leaders who had too much influence on the group decision-making process [

52]. This phenomenon is a very real and a frequent one, mainly in smaller structures which that are heavily dictated by informal relationships [

53]. These specific aspects do not prevent the emergence of genuine reasons for the improvement of happiness in cultural tourism experiences. Cultural tourism is one of the hugest types of leisure generating happiness [

54]. Other authors probe that responsible happiness processes are present in tourism when the visitors live altruistic and meaningful experiences [

1]. Following this research [

1] about tourism and well-being, the authors underline that cultural trips represent a combination of hedonic and

eudaimonic experiences; in some cases, difficulties and uncomfortable living situations during visits generate satisfaction because they allow tourists to reflect on their own good life and subsequently feel better and happier after the trip. Our results run parallel to the previous research which concludes that route-based tourism is valued by visitors because it offers an opportunity for adventure, personal advancement, exchange of intellectual ideas and information, curiosity and discovery. Long walking experience reactivates the body, mind and spirit, stimulates a health-oriented life and creates feelings of happiness, solidarity and commitment to one’s faith through contemplation of the beauty of nature and landscapes [

55].

The associations’ networks along the cultural tourist route are one of the most important aspects in the hosting society, as belonging to a certain social group gives people an important meaning to their lives. Furthermore, if the goals, values and traditions around the cultural tourist product are shared by more individuals, this means that it is important and significant for all the active members of those associations. Nevertheless, the relationships among these organizations are not as deep as would be desirable. Only a small number of them, as shown in Graphic 4, have a deep relation and maintain common activities and participant goals. Some of the organizations have a religious aim, and our results run parallel to those which say that religious people are more satisfied with their lives because they build social networks in their congregations [

56].

Results from a survey by World Happiness Report [

4], that questions why, how and when people are happy show that a great amount of people highlight the following reasons for their happiness and high life satisfaction: GDP per capita, social support, healthy life expectancy, freedom to make life choices and generosity, among others. These results are similar to ours, generally due to the impacts of cultural tourism on the hosting society and also in the visitors’ experiences. Some authors [

57] using the Buthan’s Happiness Index, compare two different islands in Fiji, one with tourist industry development and the other one without it. They discovered that despite the ‘tourism’ village being materially wealthier, the

nontourism villagers were happier in some significant aspects of life domains. Thus, we conclude that it is necessary to conduct more research in this area of knowledge, and discussion shows that it is important to clarify some of the contingent variables present in cultural tourism. Also, the different features of the hosting society as other individual and social variables that define happiness and happiness perception are very important. Finally, it is important to take into account vacation happiness bias in regards to affective recalling in front of affective forecasting, in the sense that recalled vacation experiences of the past are more positive than vacation experiences at the present. This is because the present is a result of affect that is controlled through affect regulation, merging with a certain degree of a social desirability bias [

58].