Abstract

Given the increasing significance of green innovation, scholars have identified environment-oriented leader behavior as a key antecedent of green innovation in firms. However, despite the fact that previous studies highlight all kinds of benefits of environment-oriented leaders’ voluntary workplace green behavior (VWGB) in and for firms, little is known about how these leaders’ VWGB could affect a firm team’s green product innovation as well as their process innovation. To narrow this research gap, this study theorizes and tests the effect of leaders’ VWGB on their team’s green innovation, as well as the mediation effect of team green efficacy belief on this relationship. Using a time-lagged research design, we collected data from 497 employees and 80 leaders in Chinese manufacturing firms. The results show that leaders’ VWGB directly affects both their team’s green product and process innovation, and facilitates the development of team green efficacy, which in turn stimulates team green innovation. This present study extends the multilevel phenomena by reinforcing the importance of leaders’ VWGB and team green efficacy on team-level green innovation, and provides practical implications on developing leadership for environmentally sustainable innovation.

1. Introduction

Innovation has been widely acknowledged as a key driver of firms’ performance by managers and scholars [1,2,3]. However, companies carrying out their innovative endeavors without considering environmental effects arising from their daily operations and activities may harm the environment, and inhibit their own long-term survival and successes [4,5]. Therefore, environmental sustainability is a key concern and an increasing source of pressure for firms’ innovation endeavors [6,7]. In this serious situation, firms are increasingly concentrating on how to shift their innovation activities to be more green-oriented [8,9,10,11], which implies that both product and process innovations may motivate firms to show more concern for environmental sustainability [12].

Reflecting the growing importance of green issues for firms, scholars have begun to identify the predictors that account for much of firms’ attention to environmental innovation [13]. Specifically, empirical evidence indicates that leaders can facilitate organizational greening innovation by influencing employees’ pro-environmental behaviors [14,15]. Although existing research suggests that organizational greening efforts depend on leaders’ voluntary behaviors towards green innovation issues [16], there is little knowledge on the impact of such leaders’ voluntary workplace green behavior (VWGB), which refers to discretionary individual behaviors that improve the environmental sustainability of the focal firm, but are not induced, regulated, and controlled by formal institutions relating to environmental management [17]. Thus, the main purpose of the current study is to explore the influence of leaders’ VWGB on followers’ green innovative outcomes.

To address such important yet relatively understudied issues, we construct a mediation model to study the effect of leaders’ VWGB on team green innovation [18,19]. Building on role model perspectives [15] and social cognitive theory (SCT) [20], we posit that team green efficacy can influence “leaders’ VWGB—team green innovation” link as a mediator. Furthermore, to depict a more vivid picture of green innovation benefiting business, we divide green innovation into two dimensions—i.e., green product innovation and green process innovation [4]. Green innovation as defined here includes behaviors such as preventing pollution, recycling waste, and (re)designing green products [21,22]. Thus, we anticipate that leaders’ VWGB effects can establish the basis for environmental actions within a team to enhance their beliefs about their own capabilities of achieving green innovation (i.e., team green efficacy), and then results in increased levels of team green product and process innovation.

Through addressing the questions—i.e., whether and how leaders’ VWGB exerts influence on their team’s green innovation in order to realize organizational green achievements, this study aims to enrich the green innovation literature in several directions. First, by broadening an understanding of the association between VWGB and team green innovation, this paper is among the first initiatives that stress the significance of leaders’ VWGB [1]. In doing so, we go beyond existing research on individual and firm levels of analyses and provide empirical evidence of ‘leader–team level green innovation’ relations [13,19]. Second, our study explores the motivational explanatory mechanisms linking leaders’ VWGB and multiple forms of team green innovation (i.e., green product and process innovation). By applying SCT, we extend green efficacy beliefs into a shared construct (i.e., green team efficacy) to comprehensively understand the collective efficacy discussed in the green innovation literature. Finally, our rigorous research design involving multiple sources and two-wave data collection significantly establishes our research results, which further provides more persuasive managerial implications to help organization leaders to manage their teams’ green innovation effectively.

2. Research Background

Existing research has indicated that employees’ green innovation activities can be significantly stimulated by contexts, especially by green-oriented factors [23,24]. Among this line of research, scholars highlight that supervisors’ leadership styles or supervisory behaviors as special contextual factors can significantly influence followers’ green outcomes [4,25]. Given that leaders act as a role model to effectively activate followers’ similar activities [15], leaders’ green-oriented behaviors are more likely to boost followers’ green innovative outcomes. Consistently, it is reasonable to propose that leaders’ VWGB can engage employees in green innovation endeavors [19]. Specifically, as leaders’ VWGB refers to leaders’ discretionary behaviors and activities that benefits the eco-friendly organization in a sustainable way but are not controlled by the official policy or system of environment protection [19], leaders who display VWGB frequently enact eco-friendly behaviors to reinforce the significance of green endeavors in a workplace where employees are supported to improve the company’s environmental performance [24].

Furthermore, green achievements involve multilevel phenomena [26] as has been examined in previous research [15]. Leaders’ pro-environmental behaviors may not only facilitate the development of sustainable innovation processes in the organizations by highlighting the exchange of green knowledge and information [27], but can also encourage followers to initiate green endeavors through role modeling [25]. Considering the argument that team structure can nurture innovation [18,28], and that “leadership may have its most important consequences for teams and thus a focus on the team level is also important” [29] (p. 610), we propose a significant relationship between leaders’ VWGB and team green innovation.

Moreover, accumulated evidence indicated that leaders’ environmentally-specific behaviors towards environmentally-specific outcomes are invariably indirect [15] through psychological motivations such as efficacy beliefs and psychological satisfaction [19,30]. Following this stream of research, scholars are calling for exploring the environmentally-specific motivation as a mechanism by which leaders’ green behaviors or leadership styles (e.g., VWGB) are linked to team green innovation [19]. In particular, drawing on SCT [20], there is consistent evidence suggesting that leaders promote followers’ efficacy beliefs about their green capabilities, which benefit their efforts towards improving green and environmental achievements [31,32,33]. Inspired by the theoretical argument that VWGB signals motivations [19], an extension to the group level of analysis—i.e., team green efficacy [34]—is therefore introduced to explain the indirect influence of leaders’ VWGB on team green innovation.

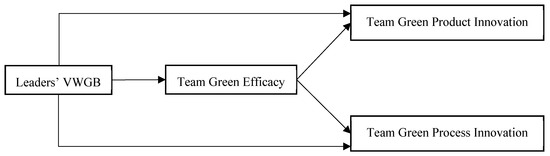

Previous studies implied an indirect influence of leaders’ VWGB on team green innovation. However, focusing on a general dimension of team green innovation may reveal limited knowledge of how leaders’ VWGB determine the specific team green innovation behaviors [22]. Some of these studies state that green innovation includes behaviors such as preventing pollution, recycling waste, and (re)designing green products. Accordingly, scholars suggested to divide green innovation into two dimensions—i.e., green product innovation and green process innovation [4]. Considering the above, we intend to study the effect of leaders’ VWGB on team green efficacy, which would lead to performance improvement of team green product and process innovation (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Research framework.

3. Theory and Hypotheses

3.1. Leaders’ Voluntary Workplace Green Behavior and Team Green Innovation

Scholars have theoretically suggested the importance of a certain leadership behavior—i.e., leaders’ VWGB—in the green innovation literature [15,35,36,37]. Corresponding to a growing need to identify a suitable supervisory behavior to specifically predict green innovation [35,38,39], leaders’ VWGB integrating a “green” perspective can specifically and significantly promote green innovative outcomes. Given that leaders act as a role model to effectively activate followers’ similar activities [15], leaders’ VWGB can engage employees in green innovation endeavors [19]. Specifically, as a role model, leaders can influence their followers to complete tasks in a similar way to the way that they do so [40]. The characteristics of leaders’ VWGB include promoting information exchange on environmental issues, emphasizing recycling activities, and encouraging eco-friendly office supplies. These enable employees to experience the significance of green behaviors during the processes of innovation engagements [19]. Thus, when strong environmental values are induced onto employees, these employees develop a growing willingness to put more efforts towards green innovative achievements.

Despite the accumulated evidence of the benefits of leaders (e.g., leaders’ VWGB) on green innovation, to date the investigations at the team level are rare [18,41]. That is, although scholars have continuously suggested that studying environmental issues involves multiple levels of investigation [26], existing research has lacked the ability to clearly depict the influences of leaders’ VWGB on team-level green innovation. We posit the potential influence of leaders’ VWGB on team green innovation for the following two reasons. First, in the leadership literature, scholars have suggested that leaders may exert greater influences on team-level outcomes [1]. Second, given the fact that teams can generate more green outcomes that facilitate the implementations of environmental practices [18], investigations on the team unit are more important for solving environment-related problems and improving green innovation.

Green innovation usually contains two main aspects: green product innovation and green process innovation [4,42]. Specifically, green product innovation is defined as products that exert less harmful effects on the environment [5], while green process innovation is defined as the production and use of goods in an eco-friendly way and that has a less harmful effect on the environment [5,43]. Overall, green product innovation generates value by making innovative products without damaging the environment [44,45], while green process innovation is environmentally friendly through developing and upgrading the processes of producing goods throughout its manufacturing cycle [46,47].

At the team level, leaders play a core role of organizing and leading their team to accomplish a set goal. During this process, leaders enact their green behaviors voluntarily, which shows their commitment to green innovative goals [19]. Meanwhile, as building teams is an important aspect of leader activities, a leader highlighting the collective interests may organize and encourage team members working together for the benefits of the whole team [48]. Accordingly, employees within a team give high value to their attachment to the team and contribute to the green development of their own team. Furthermore, leaders who engage themselves into the green activities voluntarily may create a desirable working environment where collective green-oriented behaviors are highly encouraged [19]. When employees are working collectively, they may gradually establish a strong motivation of pursuing green innovative achievements together with their teammates. This rationale suggests that leaders who employ VWGB explicitly exemplify team values of green innovation; therefore, employees realize that their collective green efforts are highly valued [13,18]. Consequently, they tend to pursue their teams’ best interest by pursuing green innovation.

Taken together, we expect that leaders’ VWGB effectively stimulate team members to work together towards team green innovation. On the one hand, leaders’ VWGB boost the utilization of team knowledge, leadership, and ability to produce green products [25,49]. On the other hand, leaders’ VWGB inspire teams to successfully implement environmental friendly criteria to develop manufacturing processes of green innovative products [50]. This leads to the first two hypotheses:

H1.

Leaders’ VWGB is positively related to team green product innovation.

H2.

Leaders’ VWGB is positively related to team green process innovation.

3.2. The Mediator of Team Green Efficacy

Drawing on SCT [20,34], we further explore the motivational processes by which leaders’ VWGB contributes to team green innovation. Generally, we consider the environmentally-specific motivation as a mechanism by which leaders’ VWGB is linked to team green innovation. Existing research on explaining the intervening mechanism of leaders’ green innovation illustrates the mediating role of individual psychological states (e.g., environmental passion, spirituality, and intrinsic motivation) [15,35]. Consistently, from a theoretical standpoint, the motivational perspective advocates that leaders motivate subordinates to be more confident in their work and obtain willingness to spend their energy to complete their tasks; therefore, they perform better and innovatively [51]. Akin to this line of literature, SCT is widely applied to explain the influence of leaders on innovative outcomes. Suggesting that people striving to be agentic have strong motivations towards their achievements [34], SCT highlights that the construction of an efficacy belief determines whether individuals can ultimately succeed in their own way [52]. Specifically, employees with a stronger self-efficacy belief are more confident in their capabilities of doing well and show persistence when facing setbacks. As a result, they are internally motivated to perform well in their tasks [53]. In line with the above theoretical reasoning, previous studies have provided accumulated evidence to support that when leaders display a specific leadership style (e.g., transformational leadership) or conduct certain behavior (e.g., supervisory mentoring), employees’ self-efficacy belief is more likely to increase, which in turn enhances their task performance and other desirable behaviors [53].

Inspired by the theoretical argument that VWGB signals motivations [19], an extension to the group level of analysis—i.e., team green efficacy [34]—is therefore introduced to explain the indirect influence of leaders’ VWGB on team green innovation. Team efficacy represents a team’s shared belief about all the team members’ joint competences of putting efforts and engaging activities in the processes of achieving a team goal [54]. It specifically highlights the property of a whole group or team through interactions among members towards high team efforts and task performance. Empirically, researchers have found that leaders can enhance the team efficacy beliefs by means of their function as a role model, which in turn helps to achieve desirable outcomes [48,55].

3.3. Leaders’ Voluntary Workplace Green Behavior and Team Green Efficacy

Previous studies have empirically indicated that leaders’ behaviors act as a crucial proximal predictor of team efficacy belief [48,56,57]. According to SCT, leadership styles or behaviors, as a sort of desirable contextual factors, contribute to the development of collective efficacy. Theoretically, leadership by a leader who demonstrates his or her commitment to a certain type of work or behavior, increases the possibility of subordinates receiving the information and guidance about how to work effectively in a similar way with this leader’s intention [58]. Extending this line of reasoning, empirical studies have been conducted to examine various leadership styles or supervisory behaviors (e.g., green transformational leadership, and empowering leadership) [31,55]. Following earlier work, we propose that leaders who display green behaviors voluntarily stimulate employees working together to pursue a teams’ best interest.

Leaders’ VWGB can positively help team members to build the team confidence of accomplishing green tasks through stimulating their motivation. Specifically, by providing environmental-related direction, leaders’ VWGB signals that the shared values of the team on achieving green outcomes are highly encouraged. To realize this goal, leaders emotionally inspire team members’ identity to the team’s identification with green issues [59]. Moreover, since leaders’ VWGB is characterized by the motivation and willingness of putting efforts on green activities [19], team members may cultivate an attitude of working together on similar activities through interactions and communications [32]. As a result, their shared efficacy belief about green endeavors can be formed. Therefore, we argue that when leaders demonstrate their voluntary behavior on green issues, the teams’ efficacy beliefs about their (teams’) capabilities of engaging and accomplishing green tasks will increase. This leads to the third hypothesis:

H3.

Leaders’ VWGB is positively related to team green efficacy.

3.4. Team Green Efficacy and Team Green Innovation

According to SCT [20], collective efficacy facilitates a team’s desirable outcomes (e.g., performance and behaviors) by encouraging all of the team members while they complete their tasks [57]. Extending this conceptualization into the green research field, the specific team-level green efficacy beliefs represent team members’ shared belief about the team’s confidence of achieving a green goal by working together [31]. According to the arguments in SCT [20], the high levels of team green efficacy represent the team member’s valuation of his/her team’s collective capacity to be successful in completing green endeavors [60]—this can effectively and significantly assist teams in facing obstacles and persisting to resolve a problem. Specifically, team members with a high level of team green efficacy tend to exert efforts which fuel the success of green innovation [31]. Furthermore, since green innovation requires persistence to address the potential risks and challenges during the processes of coming up and implementing innovative output, green efficacy may work as a support factor [32]; as a result, the teams’ norms, values, and belief around green innovative activities are embodied as a significant form of ‘DNA’ among the team members [56,59]. Thus, the teams are more likely to devote their time to developing new products, services or processes in a green manner. In contrast, team members without a belief about their team’s capabilities of performing better due to inadequate knowledge are likely to refuse to do green tasks because they have decreased motivations and passions. Accordingly, their tendency to engage in green innovative activities decline [15]. In summary, extending the previous finding of the benefits of green team efficacy on green outcomes [31], we argue that team green efficacy may positively impact both green product and process innovation at the team level, leading to the next two hypotheses:

H4.

Team green efficacy is positively related to team green product innovation.

H5.

Team green efficacy is positively related to team green process innovation.

3.5. A Mediation Model

An increasing number of studies have confirmed that leaders’ environmentally-specific behaviors towards environmentally-specific outcomes are invariably indirect [15] through psychological motivations such as efficacy beliefs [19,30]. In particular, drawing on SCT [20], there is consistent evidence suggesting that leaders promote followers’ efficacy beliefs about their green capabilities, which benefit their green efforts towards environmental achievements such as green innovation [31,32,33]. Integrating H1 and H5, we claim our theoretical argument in a mediation model—that is, the relations between leaders’ VWGB and both team green product and green process innovation are partially mediated by team green efficacy. Specifically, when leaders enact VWBG, their teams form and maintain their team green efficacy belief, which in turn facilitates their efforts on producing green innovative products, as well as improving green innovative processes. The expectations are consistent with the relevant theoretical and empirical findings [13] showing that motivation-oriented characteristics establish the intervening process through which the factors of leaders impact green behaviors. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H6.

Team green efficacy mediates the positive relationship between leaders’ VWGB and team green product innovation.

H7.

Team green efficacy mediates the positive relationship between leaders’ VWGB and team green process innovation.

4. Methods

4.1. Procedure and Participants

We collected data from 31 manufacturing firms in eastern China by using structured questionnaire surveys. Before submitting our surveys to employees and leaders, we contacted the HR departments of these companies to discuss the rationale of the current study and confirm that green innovation is an aspect of the organization’s strategy, values, and culture and to ensure that the company is a company in which VWGB can be traced and found. All the HR managers agreed to the request and invited the authors to complete data collection in their respective organizations. Afterwards, we asked HR departments to help us submit questionnaires to participants (i.e., employees and their direct supervisors) during their working time. Specifically, we distributed survey questionnaires to 750 employees to rate their perception of leaders’ VWGB, team green efficacy, and their demographic information (e.g., gender, age, and education level) during Time 1. We received usable surveys from 497 employees after deleting incomplete questionnaires. One month after the initial survey (Time 2), we distributed survey questionnaires to the leaders of these 497 employees. We received usable surveys from 80 leaders.

To guarantee confidentiality, all participants involved were informed on the objectives of this survey at the very beginning. Meanwhile, they were also informed about the data and results being used confidentially in this research. Since participants all filled the paper-pencil questionnaires during office hours, the authors were able to be with them from the beginning to the end of the data collection. When the participants completed the survey, they returned it to the researchers directly.

The 497 respondents were from 31 companies in equipment manufacturing (35%), information technology (26%), biotechnology (19%) and electric machines (20%) industry, respectively. Among these employees, 52.1% were male and most of them (65% employees) reported their age to be from 26 to 35 years. The most frequently reported education level was having an associate degree (60% employees). Team leaders were from 80 teams in 31 manufacturing firms. Leaders’ average age was 30.87 years (SD = 5.46) and 64.40% were male, the average organizational tenure was 7.5 years (SD = 7.00), and 58.7% possessed a bachelor’s degree or higher.

4.2. Measurements

We used validated English scales from previous literature, and a back-translation method to provide a Chinese instrument [61]. Seven-point Likert scales (from 1 = strongly disagree, to 7 = strongly agree) were used.

Leader’s VWGB. A six-item scale from Kim and coauthors [19] was used to measure leaders’ VWGB (Cronbach’s α = 0.90). Our questionnaire asked employees to rate the extent to which their supervisors exert VWGB. One sample item is “My supervisor avoids unnecessary printing to save paper” (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Items and factor loadings.

Team green efficacy. We adopted the four-item scale [54] to measure team green efficacy belief (Cronbach’s α = 0.81). Since we specifically examined the influences of team green-oriented efficacy belief, we designed these items to explicitly represent the team members’ shared beliefs in their team’s capabilities of performing green innovative tasks. One sample item is “Our team is able to solve green tasks if we invest the necessary effort” (see Table 1).

Team green product innovation. We used the three-item scale from Chang [5] (Cronbach’s α = 0.76) and asked leaders to assess their teams’ green product innovation. One sample item is “Our team chooses the materials of the product that produces the least amount of pollution for conducting product development or design” (see Table 1).

Team green process innovation. We used the three-item scale from Chang [5] (Cronbach’s α = 0.90) and asked leaders to assess their teams’ green product innovation. One sample item is “The manufacturing process of our team effectively reduces the emission of hazardous substances or waste” (see Table 1).

Control variables. We control the following variables: employee’s age (1 = from 18 to 25 years, 2 = from 26 to 30 years, 3 = from 30 to 35 years, 4 = from 35 to 40 years, 5 = above 41 years), gender (1 = male; 2 = female), education level (1 = junior high school diploma,2 = high school/technical school diploma, 3 = Associate degree, 4 = Bachelor’s degree, 5 = Master’s degree, 6 = Doctor’s degree), working experience (in years), and working years at the company (in years).

4.3. Analytical Strategy

We first aggregated data from the individual to the team level. Because leader’s VWGB and team green efficacy both represent the shared perception about the team level’s leader behaviors (i.e., leader’s VWGB) and green belief (i.e., team green efficacy), the employees’ responses on leader’s VWGB and team green efficacy were aggregated to form a measure of the two variables at the team level. We computed rwg to evaluate the interrater agreement, ICC(1) (intraclass correlation coefficient) to evaluate the intraclass correlations, and ICC(2) to evaluate the reliability of the group means [62]. For the leaders’ VGWB, the results indicated that ICC(1) is 0.12, ICC(2) is 0.75, and the average rwg is 0.85. For the team green efficacy, the results showed that ICC(1) is 0.19, ICC(2) is 0.80, and the average rwg is 0.88. All these indicators show that our data aggregation is appropriate.

We performed a two-step analysis to test the hypotheses in the current study. First, we conducted a four-step procedure to estimate the effects of leaders’ VGWB on team green innovative outcomes through team green efficacy. That is, when we used hierarchical regression analyses by entering control variables, leaders’ VGWB, team green product/process innovation, and team green efficacy on different steps, a partial mediation is supported if four conditions are met: (1) the independent variable (i.e., leaders’ VGWB) is significantly related to the mediator (i.e., team green efficacy); (2) the independent variable is significantly related to the dependent variables (i.e., team green product/process innovation); (3) the mediator is significantly related to the dependent variable; and (4) the relationship between the independent variable and dependent variable is still significant when the mediator is present. Second, we employed the PRODCLIN program, which is widely used in mediation checking [63], to further test the stability and significance of these mediation effects. In particular, we calculated 95% confidence intervals of indirect effects derived from bias-corrected bootstrap estimates with 10,000 iterations [64]. The variables were mean-centered beforehand.

5. Results

5.1. Preliminary Analysis

We first conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to assess the discriminant validity between the focal variables. Supporting the distinctiveness of the measures, the hypothesized four-factor model (i.e., leader’s VWGB, team green efficacy, team green product innovation, and team green process innovation) revealed a reasonable fit to the data (χ2 = 253.94, RMSEA = 0.05, TLI = 0.96, CFI = 0.97), which showed a better result than other alternative models (Hu & Bentler, 1999) such as a three-factor model (i.e., team green product innovation and team green production innovation combined as one factor) (Δχ2 (4) = 1624.74, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.90, NFI = 0.89, RMSEA = 0.17), a two-factor model (i.e., team green product innovation and team green production innovation combined as one factor, and leader’s VWGB and team green efficacy combined as the second factor) (Δχ2 (4) = 1624.74, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.90, NFI = 0.89, RMSEA = 0.17), and the single factor model (i.e., the four variables as a combined factor) (Δχ2 (5) = 2347.80, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.88, NFI = 0.86, RMSEA = 0.19). These results suggest our variables were distinguishable.

We present the descriptive statistics of variables in Table 2. It is observed that the means of team green product innovation and team green process innovation are 4.95 (SD=0.37) and 5.02 (SD = 0.4), respectively. This shows that leader’s VWGB is significant correlated with team green product innovation (= 0.12, p < 0.05) and team green process innovation (= 0.34, p < 0.05), and the correlation coefficients present the expected positive sign. As discussed, the team green efficacy positively correlates to team green product (= 0.22, p < 0.05) and process innovation ( = 0.35, p < 0.05). All variance inflation factors (VIFs) are below thumb value 5, which clearly demonstrate that multicollinearity is not a serious issue in this study.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics, correlations between variables, and variance inflation factors (VIFs).

5.2. Hypotheses Testing

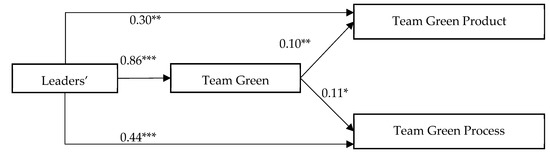

We applied a hierarchical regression method to test the proposed hypotheses, and the empirical results are presented in Table 3. We set team green product innovation, team green process innovation, and team green efficacy as dependent variables in Model1, Model2, and Model3, respectively. Our Hypothesis 1 stated a positive influence of leader’s VWGB on team product innovation. To test H1, we set the team green product innovation as the dependent variable, then included control variables in step 1 (Model1A) (R2 = 0.31, F = 5.48). In step 2, we regressed leaders’ VWGB on team green product innovation (Model1B). The result presents that leaders’ VWGB is positively associated with team green product innovation (β = 0.30, p < 0.05); and the statistical significance of all control variables are consistence with Model1A. In addition, the change of R2 (ΔR2 = 0.05, p < 0.05) indicated that leaders’ VWGB is appropriate to explain team green product innovation. Taken together, we concluded that a higher VWGB of a team’s leader can lead to more green product innovation at the team level. Thus, H1 obtained support.

Table 3.

Results of hierarchical regression analyses of collective efficacy and team creativity.

In Hypothesis 2, we proposed that leaders’ VWGB enhances team green process innovation. Model 2 of Table 2 provides empirical evidence to test H2. In step 1, we run a null model that only included control variables (Model2A) (R2 = 0.19, F = 2.91). In step 2, we added leaders’ VWGB into the model (Model2B) (R2 = 0.29, F = 4.18). The result shows a positive influence of leaders’ VWGB on team process innovation (β = 0.44, p < 0.001, Model2B). Additionally, the changed R2 increased significantly, lending statistical support for Model2B (ΔR2 = 0.10, p < 0.05). Thus, H2 obtained support.

Hypothesis 3 predicted a positive influence of leaders’ VWGB on team green efficacy. To test H3, we first regressed control variables on team green efficacy (Model3A) (R2 = 0.19, F = 2.76), then entered leaders’ VWGB (Model3B) (R2 = 0.27, F = 3.87). The change of R2 indicated that the statistical model is significantly improved (ΔR2 = 0.09, p < 0.05). The Model3B shows that the coefficient of leaders’ VWGB is positive and is significantly different from 0 (β = 0.87, p < 0.001). This result lends empirical evidence to support H3.

H4 and H5 intend to search for a relationship between team green efficacy, team green product, and process innovation. H4 stated a positive effect of team green efficacy on team green product innovation. To test H4, we added team green efficacy as step 3 of Model 1 (Model1C). The change of R2 between step 2 and step 3 is 0.05 (p < 0.05). The coefficient and influence direction of team green efficacy (β = 0.10, p < 0.05) indicate that Hypothesis 4 obtained support. As shown in H5, we posited that team green efficacy exerts a positive effect on team process innovation. To test H5, we entered team green efficacy as step 3 of Model 2 (Model2C). Our empirical results of Model2C clearly display that team green efficacy can lead to an improvement of team green process innovation (β = 0.11, p < 0.10). Therefore, empirical findings support H5. Taken together, Hypothesis 1-5 are validated and are all supported (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The results of hierarchical regression. *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

H6 and H7 both posit a mediation effect. That is, that team green efficacy mediates the positive relationship between leaders’ VWGB and team green product/process innovation. Empirical results in Table 3 imply these mediation effects. To further substantiate the mediation effects of team green efficacy, we conducted Sobel tests [65]. Results show that the mediation effects of team green efficacy for leaders’ VWGB to team product innovation (β = 0.09, p < 0.10) and to team process innovation (β = 0.10, p < 0.10) are significant. To obtain unbiased results, we further performed a bootstrapping analysis to detect statistical power of these mediation effects [66]. The bootstrapping results in Table 4 suggest that the mediation effect of team green efficacy between leaders’ VWGB and team green product innovation is 0.09, and the 95% confidence interval (0.00 0.27) of this mediation effect is exclusively 0. Table 4 also indicates that the influence of leaders’ VWGB through team green efficacy on team green process innovation is 0.09, and the 95% confidence interval (0.00 0.30) of this mediation effect also excluded 0. These bootstrapping analyses suggest that our Sobel test of mediation effects is robust. Thus, hypotheses concerning mediation effects (i.e., H6 and H7) are supported.

Table 4.

Results of bootstrapping analysis.

In summary, all the hypotheses in the current study were supported, which is summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Conclusion of testing all the hypotheses.

6. Discussion

6.1. Theoretical Implications

Our study fills a theoretical void in the literature by linking leaders’ VWGB and green product and process innovation at the team level. Firstly, our findings suggest a positive effect of leaders’ VWGB on team green innovation, which support the argument that leaders and the influence on their teams positively influence firms’ green innovation that contributes to environmental issues. The leader’s behavioral signals and the team’s green initiatives jointly provide further support to a firms’ green innovation. In this regard, leaders can effectively motivate followers’ collective voluntary attempts to innovate in green products and processes in their firms. These findings complement with previous studies that mainly explored green innovation at the single levels of individuals and firms [15,25,50,67,68]. We extend previous research suggesting that leaders’ VWGB benefits firms’ green outcomes by providing empirical evidence that explicitly shows that leaders’ VWGB can arouse their teams’ sense of strong relevance to the green innovation-related process.

Next, this study confirms the mediation effect of team green efficacy. That is, when leaders demonstrate green behaviors voluntarily, their teams are more likely to maintain and develop their collective confidence about green innovative achievements (i.e., team green efficacy). In this situation, where teams display high levels of green efficacy, team members would work together (e.g., interactions and communications) to increase their efforts on producing green innovative products and developing green innovative processes. This finding responds to repeated calls by scholars to ‘open the black-box’ of how leaders’ environmental behaviors contribute to green innovative outputs [15]. Specifically, the current study explicitly identifies an important intervening mechanism—team green efficacy—that links the relation between leaders’ VWGB and both team green product innovation and team green process innovation. Since internal motivations can effectively stimulate innovation, existing research has highlighted and established the motivational mechanisms (e.g., efficacy belief) through which leaders facilitate green innovation in organizations [31].

Our findings indicate that team green efficacy contributes to team green product and -process innovation. From this finding it could be inferred that teams with high green efficacy significantly contribute to firms’ green innovation activities (e.g., developing new and green products or processes). For example, when employees are working in a team that is characterized by a high awareness of green affairs, these employees may understand the power of teamwork towards green innovative achievements. Accordingly, this finding may support a growing interest in investigating the team characteristics of green efficacy beliefs in the organizations pursuing green innovative endeavors [31]. Specifically, we expand this research stream by providing a deepened understanding of the proposed influences of a specific psychological attribute at the team level.

6.2. Practical Implications

Our empirical findings reveal several practical implications for organizations. First, given the significant role of leaders’ VWGB in achieving green innovation, leaders should focus on displaying their voluntary behaviors in green issues. Accordingly, organizations that are concerned with green innovation need to emphasize the development of the managers’ abilities of enacting VWGB. Practically, firms should not only attempt to select and identify qualified individuals who exhibit VWGB as potential leaders, but also provide specific training, coaching, and development programs to improve their managers’ abilities of employing VWBG during their daily managerial activities.

Our findings suggest the benefits of leaders’ VWGB in fostering green innovation; thus, managers should perform the critical role of cultivating their team members’ confidence in engaging in green innovative activities. Specifically, leaders should select candidates to organize an effective team with a relatively high level of green efficacy. In doing so, these team members can work together and motivate and stimulate each other to produce green innovative products and processes. Meanwhile, leaders should exert certain behaviors themselves to specifically develop the collective efficacy beliefs about their teams’ capabilities of realizing green innovations. For example, team leaders are encouraged to create a green environment at the workplace and participate in green activities with team members.

6.3. Limitations and Avenues for Further Research

This study involves two limitations which may direct future research. First, since the samples are from sectors in manufacturing industry, the generalizability of our results is limited. Future research is thus encouraged to be conducted in such industries as for example service industry to be able to further generalize results. For example, since favoring environmental practices have been examined as a key driver of eco-friendly products in the processes of building a green hotel [69], it is reasonable to propose that leaders’ voluntary green behavior and attitudes may boost team members’ ability to work together to realize green innovative achievements.

Moreover, given the results of the partial mediation effects, future research may explore other potential psychological mechanisms that transfer the positive influence of leaders’ VGWB on green innovation at the team level. For instance, from the goal perspective, when leaders demonstrate voluntary green behavior, team members working together may perceive the importance of green innovation [70]; therefore, their teams’ goal of engaging in green activities could be built towards green innovation. Moreover, since previous studies have illustrated that followers’ positive emotions (e.g., harmonious passion for environmental sustainability) driven by leaders’ green-oriented behavior would increase their (followers’) environmental behavior [15], future research could expand on this and assess leaders’ specific green voluntary behavior exerting effects on team level support and motivation towards achieving environmental sustainability and then on multiple green innovative outcomes.

7. Conclusions

Drawing on role model perspectives [15] and SCT [20], this paper examines the direct influence of leaders’ VWGB on team’s green product and process innovation, and also particularly on how team green efficacy mediates leaders’ VWGB on team’s green innovation. This study finds a positive relationship between leaders’ VWGB and both team’s green production and process innovation. Moreover, the empirical findings confirm a mediation effect of team green efficacy on the ‘leaders’ VWGB–team green innovation’ relationship. These findings contribute to the development of green innovation studies in several ways. First, they enrich our understanding of the multilevel phenomena of green innovation by linking leaders’ VWGB, team green efficacy, and team-level green innovation. Second, by drawing on SCT, the study answers calls in the literature for more research on the mechanisms that mediate the influence of leader’s behavior on their team’s green innovation activities and output. In doing so, we provide empirical evidence for the mediating effect of team green efficacy belief.

Based on the findings of this study, it can be concluded that future research is needed to further study the supporting role of leadership styles and supervisory behaviors in their team’s green activities, processes and results. For example, according to the reported positive influence of servant leadership on innovation [71], scholars recently suggest that green servant leadership can predict a wide range of desirable ecologically friendly outcomes [72]. Green servant leadership may specifically convey a prominent signal to followers showing that green activities are highly important and encouraged by leaders; thus, studies in the future can extend this line of literature by examining whether and how green servant leadership can support green innovative outcomes. Moreover, given that the results indicate that team green efficacy partially mediates the leaders’ VWGB and their teams’ green innovation, the findings also suggest a need for future research on alternative mediating mechanisms. For example, recent meta-analytical research suggests that prosocial motivation—i.e. the will to do things that benefits others, society and nature - is an important mechanism that links contextual factors (e.g., leadership styles or supervisory behaviors) and innovative and creative outcomes [73]. Studies on the mediating role of green prosocial motivation on the effect of leadership on teams’ green innovation may lead to new and deep insights into the psychological mechanisms that support and stimulate the impact of green leadership on the green behavior of teams.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.C. and C.Y.; methodology, C.Y.; software, C.Y.; validation, W.C., C.Y. and B.A.G.B.; formal analysis, C.Y.; investigation, W.C.; resources, J.F.; data curation, W.C.; writing—original draft preparation, W.C.; writing—review and editing, W.C.; C.Y.; B.A.G.B.; visualization, C.Y.; supervision, B.A.G.B.; project administration, W.C.; funding acquisition, J.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Nature Science Fund of Hainan Province, grant number 717044, by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 71704041, and by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, grant number WK2160000013.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Anderson, N.; Potočnik, K.; Zhou, J. Innovation and creativity in organizations: A state-of-the-science review, prospective commentary, and guiding framework. J. Manag. 2014, 40, 1297–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossan, M.M.; Apaydin, M. A multi-dimensional framework of organizational innovation: A systematic review of the literature. J. Manag. Stud. 2010, 47, 1154–1191. [Google Scholar]

- Piening, E.P.; Salge, T.O. Understanding the antecedents, contingencies, and performance implications of process innovation: A dynamic capabilities perspective. J. Prod. Innov. Manage. 2015, 32, 80–97. [Google Scholar]

- Albort-Morant, G.; Henseler, J.; Cepeda-Carrión, G.; Leal-Rodríguez, A.L. Potential and realized absorptive capacity as complementary drivers of green product and process innovation performance. Sustainability 2018, 10, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-H. The influence of corporate environmental ethics on competitive advantage: The mediation role of green innovation. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 104, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Chen, W. Environmental regulation, green innovation, and industrial green development: An empirical analysis based on the Spatial Durbin model. Sustainability 2018, 10, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Leeuwen, G.; Mohnen, P. Revisiting the Porter hypothesis: An empirical analysis of green innovation for the Netherlands. Econ. Innov. New Technol. 2017, 26, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Tsai, S.B.; Xue, X.; Ren, T.; Du, X.; Chen, Q.; Wang, J. An Empirical Study on Green Innovation Efficiency in the Green Institutional Environment. Sustainability 2018, 10, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Xia, X.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, D. Environmental Regulation, Government R&D Funding and Green Technology Innovation: Evidence from China Provincial Data. Sustainability 2018, 10, 940. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Yin, Q.; Pan, Y.; Cui, W.; Xin, B.; Rao, Z. Green product innovation and firm performance: Assessing the moderating effect of novelty-centered and efficiency-centered business model design. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Xue, Y.; Yang, J. Impact of environmental regulations on green technological innovative behavior: An empirical study in China. J. Clean Prod. 2018, 188, 763–773. [Google Scholar]

- Triguero, A.; Moreno-Mondéjar, L.; Davia, M.A. Drivers of different types of eco-innovation in European SMEs. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 92, 25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Norton, T.A.; Parker, S.L.; Zacher, H.; Ashkanasy, N.M. Employee green behavior: A theoretical framework, multilevel review, and future research agenda. Organ. Environ. 2015, 28, 103–125. [Google Scholar]

- Ángel del Brío, J.; Junquera, B.; Ordiz, M. Human resources in advanced environmental approaches–a case analysis. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2008, 46, 6029–6053. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, J.L.; Barling, J. Greening organizations through leaders’ influence on employees’ pro-environmental behaviors. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 176–194. [Google Scholar]

- D’Mello, S.; Ones, D.; Klein, R.; Wiernik, B.; Dilchert, S. Green company rankings and reporting of pre-environmental efforts in organizations. In Proceedings of the Poster session presented at the 26th Annual Conference of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Chicago, IL, USA, 14–16 April 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Boiral, O. Greening the corporation through organizational citizenship behaviors. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 87, 221–236. [Google Scholar]

- Jabbour, C.J.C.; Santos, F.C.A.; Fonseca, S.A.; Nagano, M.S. Green teams: Understanding their roles in the environmental management of companies located in Brazil. J. Clean Prod. 2013, 46, 58–66. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, A.; Kim, Y.; Han, K.; Jackson, S.E.; Ployhart, R.E. Multilevel influences on voluntary workplace green behavior: Individual differences, leader behavior, and coworker advocacy. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1335–1358. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. The explanatory and predictive scope of self-efficacy theory. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 1986, 4, 359–373. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.S.; Lai, S.B.; Wen, C.T. The influence of green innovation performance on corporate advantage in Taiwan. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 67, 331–339. [Google Scholar]

- Dangelico, R.M. Green product innovation: Where we are and where we are going. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2016, 25, 560–576. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, P.J.; Wu, T.J.; Yuan, K.S. “Green” Information Promotes Employees’ Voluntary Green Behavior via Work Values and Perceived Accountability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6335. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary, R. Green human resource management and employee green behavior: An empirical analysis. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 630–641. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H. The determinants of green product development performance: Green dynamic capabilities, green transformational leadership, and green creativity. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 116, 107–119. [Google Scholar]

- Marquis, C.; Jackson, S.E.; Li, Y. Building sustainable organizations in China. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2015, 11, 427–440. [Google Scholar]

- Bossink, B.A. Leadership for sustainable innovation. Int. J. Technol. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2007, 6, 135–149. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; Farh, J.L.; Campbell-Bush, E.M.; Wu, Z.; Wu, X. Teams as innovative systems: Multilevel motivational antecedents of innovation in R&D teams. J. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 98, 1018–1027. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, B.C.; Ployhart, R.E. Transformational leadership: Relations to the five-factor model and team performance in typical and maximum contexts. J. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 89, 610–621. [Google Scholar]

- Whitmarsh, L.; O’Neill, S. Green identity, green living? The role of pro-environmental self-identity in determining consistency across diverse pro-environmental behaviours. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 305–314. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H.; Lin, Y.H. Green Transformational leadership and green performance: The mediation effects of green mindfulness and green self-efficacy. Sustainability 2014, 6, 6604–6621. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Chen, J.; Tao, Y. Innovation Performance in New Product Development Teams in C hina’s Technology Ventures: The Role of Behavioral Integration Dimensions and Collective Efficacy. J. Prod. Innov. Manage. 2015, 32, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahroum, S.; Al-Saleh, Y. Towards a functional framework for measuring national innovation efficacy. Technovation 2013, 33, 320–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Exercise of human agency through collective efficacy. Curr. Dir. Psychol. 2000, 9, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B.; Badir, Y.; Kiani, U.S. Linking spiritual leadership and employee pro-environmental behavior: The influence of workplace spirituality, intrinsic motivation, and environmental passion. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 45, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flannery, B.L.; May, D.R. Prominent factors influencing environmental activities: Application of the environmental leadership model (ELM). Leadersh Q. 1994, 5, 201–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, N.J.; Cialdini, R.B.; Griskevicius, V. A room with a viewpoint: Using social norms to motivate environmental conservation in hotels. J. Consum. Res. 2008, 35, 472–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egri, C.P.; Herman, S. Leadership in the North American environmental sector: Values, leadership styles, and contexts of environmental leaders and their organizations. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 571–604. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, E.; Junquera, B.; Ordiz, M. Managers’ profile in environmental strategy: A review of the literature. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2006, 13, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elenkov, D.S.; Manev, I.M. Top management leadership and influence on innovation: The role of sociocultural context. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 381–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, C.L.; Ensley, M.D. A reciprocal and longitudinal investigation of the innovation process: The central role of shared vision in product and process innovation teams (PPITs). J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 259–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utterback, J.M.; Abernathy, W.J. A dynamic model of process and product innovation. Omega 1975, 3, 639–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S. Green organizational identity: Sources and consequence. Manage. Decis. 2011, 49, 384–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangelico, R.M.; Pujari, D. Mainstreaming green product innovation: Why and how companies integrate environmental sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubik, F.; Frankl, P.; Pietroni, L.; Scheer, D. Eco-labelling and consumers: Towards a re-focus and integrated approaches. Int. J. Technol. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2007, 2, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, T.Y.; Chan, H.K.; Lettice, F.; Chung, S.H. The influence of greening the suppliers and green innovation on environmental performance and competitive advantage in Taiwan. Transp. Res. Logist. Transp. Rev. 2011, 47, 822–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kam-Sing Wong, S. The influence of green product competitiveness on the success of green product innovation: Empirical evidence from the Chinese electrical and electronics industry. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2012, 15, 468–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoko, O.B.; Chua, E.L. The importance of transformational leadership behaviors in team mental model similarity, team efficacy, and intra-team conflict. Group Organ. Manage. 2014, 39, 504–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A.C.; Nembhard, I.M. Product development and learning in project teams: The challenges are the benefits. J. Prod. Innov. Manage. 2009, 26, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgün, A.E.; Keskin, H.; Byrne, J. Organizational emotional capability, product and process innovation, and firm performance: An empirical analysis. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 2009, 26, 103–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.W. Transformational leadership and performance outcomes: Analyses of multiple mediation pathways. Leadersh Q. 2017, 28, 385–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierney, P.; Farmer, S.M. Creative self-efficacy: Its potential antecedents and relationship to creative performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2002, 45, 1137–1148. [Google Scholar]

- Judge, T.A.; Jackson, C.L.; Shaw, J.C.; Scott, B.A.; Rich, B.L. Self-efficacy and work-related performance: The integral role of individual differences. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 107–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salanova, M.; Llorens, S.; Cifre, E.; Martínez, I.M.; Schaufeli, W.B. Perceived collective efficacy, subjective well-being and task performance among electronic work groups: An experimental study. Small Group Res. 2003, 34, 43–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Bartol, K.M.; Locke, E.A. Empowering leadership in management teams: Effects on knowledge sharing, efficacy, and performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 1239–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Bliese, P.D. The role of different levels of leadership in predicting self-and collective efficacy: Evidence for discontinuity. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, D.I.; Sosik, J.J. Transformational leadership in work groups: The role of empowerment, cohesiveness, and collective-efficacy on perceived group performance. Small Group Res. 2002, 33, 313–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A.; Wessels, S. Self-Efficacy; W.H. Freeman & Company: San Diego, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Epitropaki, O.; Kark, R.; Mainemelis, C.; Lord, R.G. Leadership and followership identity processes: A multilevel review. Leadersh Q. 2017, 28, 104–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggs, M.L.; Warka, J.; Babasa, B.; Betancourt, R.; Hooker, S. Development and validation of self-efficacy and outcome expectancy scales for job-related applications. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1994, 54, 793–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. Methodology 1980, 2, 389–444. [Google Scholar]

- Bliese, P.D. Within-group agreement, non-independence, and reliability: Implications for data aggregation and analysis. In Multilevel Theory, Research, and Methods in Organizations; Klein, K.J., Kozlowski, S.W., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 349–381. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Fritz, M.S.; Williams, J.; Lockwood, C.M. Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect: Program PRODCLIN. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 384–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Sobel, M.E. Some new results on indirect effects and their standard errors in covariance structure models. Sociol. Methodl. 1986, 16, 159–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrout, P.E.; Bolger, N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adner, R.; Levinthal, D. Demand heterogeneity and technology evolution: Implications for product and process innovation. Manag. Sci. 2001, 47, 611–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.H.; Chen, Y.S. Green organizational identity and green innovation. Manage. Decis. 2013, 51, 1056–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.A.; Davis, E.A.; Weaver, P.A. Eco-friendly attitudes, barriers to participation, and differences in behavior at green hotels. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2014, 55, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, S.; Dhar, R.L. Effect of green transformational leadership on green creativity: A study of tourist hotels. Tourism Manag. 2016, 57, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Lysova, E.I.; Khapova, S.N.; Bossink, B.A. Servant leadership and innovative work behavior in Chinese high-tech firms: A moderated mediation model of meaningful work and job autonomy. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luu, T.T. Green human resource practices and organizational citizenship behavior for the environment: The roles of collective green crafting and environmentally specific servant leadership. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1167–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Jiang, K.; Shalley, C.E.; Keem, S.; Zhou, J. Motivational mechanisms of employee creativity: A meta-analytic examination and theoretical extension of the creativity literature. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2016, 137, 236–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).