Moderating Effect of Political Embeddedness on the Relationship between Resources Base and Quality of CSR Disclosure in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Legitimacy Theory

2.2. The Relationship between Political Embeddedness and CSR Disclosure Quality

2.3. Resource Base and CSR Disclosure

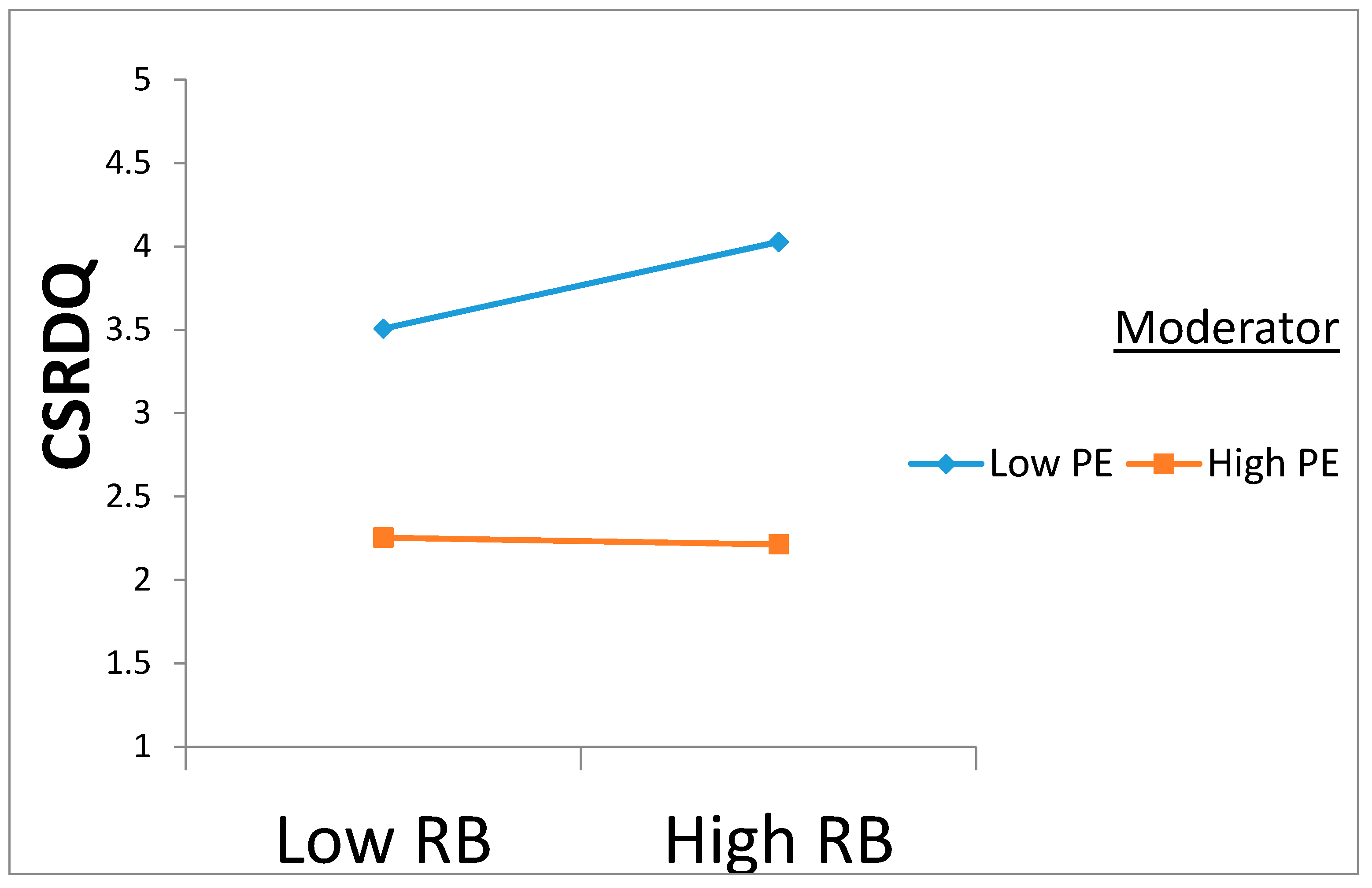

2.4. Moderating Role of Political Embeddedness

3. Methodology

3.1. Data and Sample

3.2. Empirical Model and Measures

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

3.2.2. Control Variables

3.2.3. Independent Variables

4. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Matrix

5. Analysis and Results

Endogeneity and Other Robustness Tests

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Policy Implications

6.2. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cooper, S.M.; Owen, D.L. Corporate social reporting and stakeholder accountability: The missing link. Account. Organ. Soc. 2007, 32, 649–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Qiao, M.; Che, B.; Tong, P. Regional Anti-Corruption and CSR Disclosure in a Transition Economy: The Contingent Effects of Ownership and Political Connection. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquis, C.; Qian, C. Corporate social responsibility reporting in China: Symbol or substance? Organ. Sci. 2014, 25, 127–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelson, E. Climbing the dispute pagoda: Grievances and appeals to the official justice system in rural China. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2007, 72, 459–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, A.; Matten, D.; Moon, J. Corporations and Citizenship: Business, Responsibility and Society; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dieleman, M.; Boddewyn, J.J. Using organization structure to buffer political ties in emerging markets: A case study. Organ. Stud. 2012, 33, 71–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsamenyi, M.; Uddin, S. Introduction to corporate governance in less developed and emerging economies. In In Corporate Governance in Less Developed and Emerging Economies; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2008; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Berglöf, E.; Claessens, S. Enforcement and good corporate governance in developing countries and transition economies. World Bank Res. Obs. 2006, 21, 123–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talmud, I.; Mesch, G.S. Market embeddedness and corporate instability: The ecology of inter-industrial networks. Soc. Sci. Res. 1997, 26, 419–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Miao, X.; Zheng, D.; Tang, Y. Corporate Public Transparency on Financial Performance: The Moderating Role of Political Embeddedness. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, W.; Jiang, X. Political Connections, Innovation Decision Making, and Firm Performance. In Academy of Management Proceedings; Academy of Management: Briarcliff Manor, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, X.; Dong, J. Multilevel Political Embeddedness and Corporate Strategic Discretion. In Academy of Management Proceedings; Academy of Management: Briarcliff Manor, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Lai, W.; Song, X.; Lu, C. Implementation Efficiency of Corporate Social Responsibility in the Construction Industry: A China Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, M.; Balaev, M.; Clarke, B. Political embeddedness in environmental contexts: The intersections of social networks and planning institutions in coastal land use. Environ. Sociol. 2018, 4, 286–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.; Ryan, C.; Bin, L.; Wei, G. Political connections, guanxi and adoption of CSR policies in the Chinese hotel industry: Is there a link? Tour. Manag. 2013, 34, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelan, G. The political perspective of corporate social responsibility: A critical research agenda. Bus. Ethics Q. 2012, 22, 709–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapple, W.; Moon, J. CSR agendas for Asia. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2007, 14, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Walker, M.; Zeng, C. Do Chinese government subsidies affect firm value? Account. Organ. Soc. 2014, 39, 149–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lux, S.; Crook, T.R.; Woehr, D.J. Mixing business with politics: A meta-analysis of the antecedents and outcomes of corporate political activity. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 223–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthuri, J.N.; Gilbert, V. An institutional analysis of corporate social responsibility in Kenya. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 98, 467–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prechel, H.; Morris, T. The effects of organizational and political embeddedness on financial malfeasance in the largest US corporations: Dependence, incentives, and opportunities. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2010, 75, 331–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasseldine, J.; ASalama, I.; Toms, J.S. Quantity versus quality: The impact of environmental disclosures on the reputations of UK Plcs. Br. Account. Rev. 2005, 37, 231–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutin-Dufresne, F.; Savaria, P. Corporate social responsibility and financial risk. J. Investig. 2004, 13, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.D.; RFaff, W. Corporate sustainability performance and idiosyncratic risk: A global perspective. Financ. Rev. 2009, 44, 213–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.Y.; Lee, C.; Pfeiffer, R.J., Jr. Corporate social responsibility performance and information asymmetry. J. Account. Public Policy 2013, 32, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, P.M.; Overell, M.B.; Chapple, L. Environmental reporting and its relation to corporate environmental performance. Abacus 2011, 47, 27–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroney, R.; Windsor, C.; Aw, Y.T. Evidence of assurance enhancing the quality of voluntary environmental disclosures: An empirical analysis. Account. Financ. 2012, 52, 903–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, P.; Wicks, P.G. Institutional interest in corporate responsibility: Portfolio evidence and ethical explanation. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 103, 143–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.; Kacperczyk, M. The price of sin: The effects of social norms on markets. J. Financ. Econ. 2009, 93, 15–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, H.L.; Vredenburg, H. Morals or economics? Institutional investor preferences for corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 90, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plumlee, M.; Brown, D.; Hayes, R.M.; Marshall, R.S. Voluntary environmental disclosure quality and firm value: Further evidence. J. Account. Public Policy 2015, 34, 336–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reverte, C. Determinants of corporate social responsibility disclosure ratings by Spanish listed firms. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 88, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelan, G.; Muthuri, J. Chinese state-owned enterprises and human rights: The importance of national and intra-organizational pressures. Bus. Soc. 2017, 56, 738–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.Y.; Zhu, Y.; Tucker, J.; Hu, Y. Ownership influence and CSR disclosure in China. Account. Res. J. 2018, 31, 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Zhang, Y. Institutional dynamics and corporate social responsibility (CSR) in an emerging country context: Evidence from China. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 111, 301–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, D. China and Globalization: The Social, Economic and Political Transformation of Chinese Society; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Q.; Tong, W.H.; Tong, J. How does government ownership affect firm performance? Evidence from China’s privatization experience. J. Bus. Financ. Account. 2002, 29, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, G.; Lin, B.; Liu, F. Political connections and privatization: Evidence from China. J. Account. Public Policy 2013, 32, 114–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Wu, C.; Rui, O.M. Ownership and the value of political connections: Evidence from China. Eur. Financ. Manag. 2012, 18, 695–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haveman, H.A.; Jia, N.; Shi, J.; Wang, Y. The dynamics of political embeddedness in China. Adm. Sci. Q. 2017, 62, 67–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, C.; Lu, Y.; Liang, Q. Corporate social responsibility in China: A corporate governance approach. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 136, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Zeng, T. Profitability, state ownership, tax reporting and corporate social responsibility: Evidence from Chinese listed firms. Soc. Responsib. J. 2016, 12, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.R.; Wang, D.; Zhang, J. Whose call to answer: Institutional complexity and firms’ CSR reporting. Acad. Manag. J. 2017, 60, 321–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, E.M.; Toffel, M.W. Responding to public and private politics: Corporate disclosure of climate change strategies. Strateg. Manag. J. 2009, 30, 1157–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, J.L.; Toffel, M.W. Coerced confessions: Self-policing in the shadow of the regulator. J. Law Econ. Organ. 2007, 24, 45–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oates, W.E. An essay on fiscal federalism. J. Econ. Lit. 1999, 37, 1120–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebbington, J.; Larrinaga, C.; Moneva, J.M. Corporate social reporting and reputation risk management. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2008, 21, 337–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M.L. Stakeholder influence capacity and the variability of financial returns to corporate social responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 794–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlitzky, M.; Schmidt, F.L.; Rynes, S.L. Corporate social and financial performance: A meta-analysis. Organ. Stud. 2003, 24, 403–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, N.; Deegan, C. The public disclosure of environmental performance information—A dual test of media agenda setting theory and legitimacy theory. Account. Bus. Res. 1998, 29, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darrell, W.; Schwartz, B.N. Environmental disclosures and public policy pressure. J. Account. Public Policy 1997, 16, 125–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, R.; Kouhy, R.; Lavers, S. Corporate social and environmental reporting: A review of the literature and a longitudinal study of UK disclosure. Account. Audit. Account. J. 1995, 8, 47–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deegan, C. Introduction: The legitimising effect of social and environmental disclosures–A theoretical foundation. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2002, 15, 282–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, J.; Pfeffer, J. Organizational legitimacy: Social values and organizational behavior. Pac. Sociol. Rev. 1975, 18, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindblom, C.K. The implications of organizational legitimacy for corporate social performance and disclosure. In Social and Environmental Accounting; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, P.; Mellahi, K.; Thun, E.J. The dynamic value of MNE political embeddedness: The case of the Chinese automobile industry. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2010, 41, 1161–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, N.J.M.; Review, O. Political strategy and market capabilities: Evidence from the Chinese private sector. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2016, 12, 75–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquis, C.; Raynard, M. Institutional strategies in emerging markets. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2015, 9, 291–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.W.; Luo, Y. Managerial ties and firm performance in a transition economy: The nature of a micro-macro link. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 486–501. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, W.; Singh, K.; Mitchell, W. Buffering and enabling: The impact of interlocking political ties on firm survival and sales growth. Strateg. Manag. J. 2015, 36, 1615–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonardi, J.-P.; Hillman, A.J.; Keim, G.D. The attractiveness of political markets: Implications for firm strategy. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2005, 30, 397–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faccio, M.; Masulis, R.W.; McConnell, J.J. Political connections and corporate bailouts. J. Financ. 2006, 61, 2597–2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khwaja, A.I.; Mian, A. Do lenders favor politically connected firms? Rent provision in an emerging financial market. Q. J. Econ. 2005, 120, 1371–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadani, M.; Schuler, D.A. In search of El Dorado: The elusive financial returns on corporate political investments. Strateg. Manag. J. 2013, 34, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okhmatovskiy, I. Performance implications of ties to the government and SOEs: A political embeddedness perspective. J. Manag. Stud. 2010, 47, 1020–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Anbumozhi, V. Determinant factors of corporate environmental information disclosure: An empirical study of Chinese listed companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Marquis, C.; Qiao, K. Do political connections buffer firms from or bind firms to the government? A study of corporate charitable donations of Chinese firms. Organ. Sci. 2016, 27, 1307–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Weingast, B.R. Federalism as a commitment to reserving market incentives. J. Econ. Perspect. 1997, 11, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Meng, L.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, L.A. Political connections, financing and firm performance: Evidence from Chinese private firms. J. Dev. Econ. 2008, 87, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okhmatovskiy, I.; David, R.J. Setting your own standards: Internal corporate governance codes as a response to institutional pressure. Organ. Sci. 2012, 23, 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocasio, W. Towards an attention-based view of the firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Li, L.; Feng, Y.; Wang, H.; Wei, B. The Development of China’s Primary Copper Smelting Technologies. In Proceedings of the TT Chen Honorary Symposium on Hydrometallurgy, Electrometallurgy and Materials Characterization; Wiley: Maitland, FL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, C. Strategic responses to institutional processes. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 145–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, J.A.; Oliver, C. Institutional linkages and organizational mortality. Adm. Sci. Q. 1991, 36, 187–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lounsbury, M. Institutional sources of practice variation: Staffing college and university recycling programs. Adm. Sci. Q. 2001, 46, 29–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, B.J. Red Capitalists in China: The Party, Private Entrepreneurs, and Prospects for Political Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, N. Capitalism in China: A centrally managed capitalism (CMC) and its future. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2011, 7, 63–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Lemmon, M.; Pan, X.; Qian, M.; Tian, G. Political promotion, CEO incentives, and the relationship between pay and performance. Manag. Sci. 2018, 65, 2947–2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Meng, L.; Zhang, J. Why do entrepreneurs enter politics? Evidence from China. Econ. Inq. 2006, 44, 559–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Gago, R.; Cabeza-García, L.; Nieto, M. Independent directors’ background and CSR disclosure. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 991–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, C.; Holzinger, I. The effectiveness of strategic political management: A dynamic capabilities framework. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 496–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelman, L.B. Legal ambiguity and symbolic structures: Organizational mediation of civil rights law. Am. J. Sociol. 1992, 97, 1531–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Zhao, C.; Cho, C.H. Institutional transitions and the role of financial performance in CSR reporting. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, R.; Raynard, M.; Kodeih, F.; Micelotta, E.R.; Lounsbury, M. Institutional complexity and organizational responses. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2011, 5, 317–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.W.; Rowan, B. Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. Am. J. Sociol. 1977, 83, 340–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajac, E.J.; Westphal, J.D. The costs and benefits of managerial incentives and monitoring in large US corporations: When is more not better? Strateg. Manag. J. 1994, 15, 121–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromley, P.; Powell, W.W. From smoke and mirrors to walking the talk: Decoupling in the contemporary world. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2012, 6, 483–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiss, P.C.; Zajac, E.J. The diffusion of ideas over contested terrain: The (non) adoption of a shareholder value orientation among German firms. Adm. Sci. Q. 2004, 49, 501–534. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, K.; Davis, G.F.; Lounsbury, M. Policy as myth and ceremony? The global spread of stock exchanges, 1980–2005. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 1319–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voinea, C.L.; van Kranenburg, H. Feeling the squeeze: Nonmarket institutional pressures and firm nonmarket strategies. Manag. Int. Rev. 2018, 58, 705–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferri, G.; Liu, L.-G. Honor thy creditors beforan thy shareholders: Are the profits of Chinese state-owned enterprises real? Asian Econ. Pap. 2010, 9, 50–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Parish, W.L. Tocquevillian moments: Charitable contributions by Chinese private entrepreneurs. Soc. Forces 2006, 85, 943–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dacin, M.T.; Oliver, C.; Roy, J.P. The legitimacy of strategic alliances: An institutional perspective. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 169–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartley, T.; Child, C. Movements, markets and fields: The effects of anti-sweatshop campaigns on US firms, 1993–2000. Soc. Forces 2011, 90, 425–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Qian, C. Corporate philanthropy and corporate financial performance: The roles of stakeholder response and political access. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 1159–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiseman, J. An evaluation of environmental disclosures made in corporate annual reports. Account. Organ. Soc. 1982, 7, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Lu, C.; Qi, J. Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure and Stock Price Crash Risk: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Liu, C. Quality of corporate social responsibility disclosure and cost of equity capital: Lessons from China. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2018, 54, 2472–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Song, L.; Yao, S. The determinants of corporate social responsibility disclosure: Evidence from China. J. Appl. Bus. Res. 2013, 29, 1833–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Li, W.; Lu, X. Government engagement, environmental policy, and environmental performance: Evidence from the most polluting Chinese listed firms. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2015, 24, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, P.M.; Li, Y.; Richardson, G.D.; Vasvari, F.P. Revisiting the relation between environmental performance and environmental disclosure: An empirical analysis. Account. Organ. Soc. 2008, 33, 303–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulzar, M.A.; Cherian, J.; Sial, M.S.; Badulescu, A.; Thu, P.A.; Badulescu, D.; Khuong, N.V. Does Corporate Social Responsibility Influence Corporate Tax Avoidance of Chinese Listed Companies? Sustainability 2018, 10, 4549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.U.; Zhang, J.; Usman, M.; Badulescu, A.; Sial, M.S. Ownership Reduction in state-owned enterprises and corporate social responsibility: Perspective from secondary privatization in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuinness, P.B.; Vieito, J.P.; Wang, M. The role of board gender and foreign ownership in the CSR performance of Chinese listed firms. J. Corp. Financ. 2017, 42, 75–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, R.W. Determinants of corporate social responsibility disclosure: An application of stakeholder theory. Account. Organ. Soc. 1992, 17, 595–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.J.; Li, Z.; Su, X.; Sun, Z. Rent-seeking incentives, corporate political connections, and the control structure of private firms: Chinese evidence. J. Corp. Financ. 2011, 17, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, B.; Morris, S.A.; Bartkus, B.R. Having, giving, and getting: Slack resources, corporate philanthropy, and firm financial performance. Bus. Soc. 2004, 43, 135–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carow, K.; Heron, R.; Saxton, T. Do early birds get the returns? An empirical investigation of early-mover advantages in acquisitions. Strateg. Manag. J. 2004, 25, 563–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muttakin, M.B.; Mihret, D.G.; Khan, A. Corporate political connection and corporate social responsibility disclosures: A neo-pluralist hypothesis and empirical evidence. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2018, 31, 725–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.C.; Kim, Y.H. CSR and shareholder value in the restaurant industry: The roles of CSR communication through annual reports. Cornell Hospitality Q. 2019, 60, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Zhang, J.; Usman, M.; Khan, F.U.; Ikram, A.; Anwar, B. Sub-National Institutional Contingencies and Corporate Social Responsibility Performance: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Sanchez, I.-M.; Cuadrado-Ballesteros, B.; Sepulveda, C. Does media pressure moderate CSR disclosures by external directors? Manag. Decis. 2014, 52, 1014–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopatta, K.; Jaeschke, R.; Chen, C. Stakeholder engagement and corporate social responsibility (CSR) performance: International evidence. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Ven, W.P.; van Praag, B.M. The demand for deductibles in private health insurance: A probit model with sample selection. J. Econom. 1981, 17, 229–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yao, X.; Liu, L. Value creation and value maintenance: Investigating the impact of firm capability on political networking. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2019, 13, 318–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrnström-Fuentes, M. Delinking legitimacies: A pluriversal perspective on political CSR. J. Manag. Stud. 2016, 53, 433–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surroca, J.; Tribó, J.A.; Waddock, S. Corporate responsibility and financial performance: The role of intangible resources. Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 31, 463–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J. Institutional drivers for corporate social responsibility in an emerging economy: A mixed-method study of Chinese business executives. Bus. Soc. 2017, 56, 672–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Jamali, D. Strategic corporate social responsibility of multinational companies subsidiaries in emerging markets: Evidence from China. Long Range Plan. 2016, 49, 541–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Perlines, F.; Rung-Hoch, N. Sustainable entrepreneurial orientation in family firms. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, G.; Bartosch, J.; Avetisyan, E.; Kinderman, D.; Knudsen, J.S. Mandatory non-financial disclosure and its influence on CSR: An international comparison. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 162, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Abbreviation | Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| (1) Corporate social responsibility disclosure quality | CSRDQ | The CSR report provides information conferring to ten substances regarding the listed company’s non-financial performance. CSR report is a dummy variable equal to 1 if the focal firm has issued a CSR report in a given year, and it is 0 otherwise. |

| (2) Political Embeddedness | PE | Political Embeddedness: The firm assigns value 1 if it is politically embedded and 0 otherwise. A firm is politically embedded if one of its directors, senior officers, or supervisors (i.e., chairman, president, vice president, etc.) is or was a member of the National People’s Congress (NPC), a government official, or a member of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC). |

| (3) Resource Base | RB | Resource base as total cash flow from different activities of business-like operating, investing, and financing. |

| (4) Firm Size | FS | Defined as the natural log of total assets. |

| (5) Board Size | BS | The number of directors on the board. |

| (6) Independent Director | ID | The firms will take at least 2 directors as independent directors. |

| (7) Tobin’s Q | TQ | Tobin’s Q is the percentage among a physical asset’s market value and its additional value. |

| (8) Book to Market Ratio | BTMA | Book to market ratio of shareholders equity. |

| (9) Asset Growth | AG | Asset Growth of the company is measured as the change in total assets. |

| (10) Return on Assists | ROA | Total profit is a percentage of total assets. |

| (11) Return on Equity | ROE | The ratio of total profit and percentage of equity. |

| (12) Board Meeting | BM | The number of meetings in one-year time. |

| (13) Financial Leverage | LEV | The ratio of total debt to the total asset. |

| Year and Industry | YI | To control the effect of year and industry, we included year and Industry dummies in all regressions |

| Variables | Mean | S.D. | Min | Max | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | (13) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) CSRDQ | 5.406 | 2.505 | 1 | 8 | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| (2) PE | 0.105 | 0.306 | 0 | 1 | −1.105 | 1.000 | |||||||||||

| (3) RB | 24.83 | 5.508 | 14.557 | 38.975 | −0.050 * | −0.015 * | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| (4) Firm Size | 23.192 | 1.747 | 18.265 | 30.814 | 0.044 * | −0.073 * | −0.182 * | 1.000 | |||||||||

| (5) Board Size | 9.483 | 2.282 | 4 | 22 | −0.003 * | −0.002 * | −0.100 * | 0.261 * | 1.000 | ||||||||

| (6) Independ Direct | 3.493 | 0.839 | 1 | 8 | 0.023 * | 0.007 * | −0.092 * | 0.315 * | 0.593 * | 1.000 | |||||||

| (7) Tobin’s Q | 1.752 | 1.813 | 0.096 | 33.270 | −0.081 * | 0.068 * | 0.119 * | −0.468 * | −0.169 * | −0.143 * | 1.000 | ||||||

| (8) BTMA | 1.186 | 1.153 | 0.030 | 10.328 | 0.015 * | −0.078 * | −0.110 * | 0.580 * | 0.114 * | 0.137 * | −0.488 * | 1.000 | |||||

| (9) Asset Growth | 0.166 | 0.343 | −0.828 | 10.888 | −0.035 * | 0.019 * | −0.001 | −0.023 * | −0.000 | -0.001 | 0.106 * | −0.073 * | 1.000 | ||||

| (10) ROA | 0.042 | 0.574 | −0.690 | 0.481 | −0.088 * | 0.056 * | −0.058 * | −0.066 * | −0.404 * | 0.026 * | 0.366 * | 0.350 * | 0.164 * | 1.000 | |||

| (11) ROE | 0.082 | 0.816 | −18.568 | 43.614 | −0.061 * | 0.054 * | −0.059 * | 0.084 * | 0.068 * | 0.054 * | 0.190 * | 0.180 * | 0.164 * | 0.547 * | 1.000 | ||

| (12) Board Meeting | 10.215 | 4.790 | 1 | 57 | −0.012 | −0.020 * | −0.029 * | 0.188 * | 0.029 * | −0.076 * | −0.105 * | 0.205 * | −0.017 * | −0.127 * | −0.047 * | 1.000 | |

| (13) Fin_ Leverage | 0.509 | 0.509 | 0.007 | 1.344 | 0.075 * | −0.056 * | −0.138 * | 0.458 * | 0.115 * | 0.132 * | −0.477 * | −0.607 * | −0.477 * | −0.085 * | −0.185 * | 0.241 * | 1.000 |

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSRDQ | OLS | OLS | OLS |

| PE | −0.636 *** (−4.32) | −0.514 *** (−3.52) | −0.767 *** (−5.02) |

| RB | -------------- | 0.033 *** (9.35) | 0.024 *** (6.07) |

| Interaction | -------------- | -------------- | −0.025 *** (5.35) |

| Firm Size | −0.009 (−0.21) | −0.016 (−0.37) | −0.019 (0.44) |

| Board Size | −0.049 (−1.43) | −0.049 (−1.43) | −0.050 (−1.48) |

| Independ Direct | 0.081 ** (1.93) | 0.188 ** (2.00) | 0.180 ** (1.93) |

| Tobin’s Q | 0.056 * (−1.83) | −0.055 * (−1.82) | −0.054 * (−1.79) |

| BTMA | −0.050 (−0.90) | −0.046 (−0.85) | −0.049 (−0.90) |

| Asset Growth | −0.176 (−1.33) | −0.016 (−0.12) | −0.078 (−0.59) |

| ROA | 0.440 (0.40) | −0.390 (−0.36) | 0.267 (0.24) |

| ROE | −0.485 ** (−1.96) | −0.440 ** (−1.80) | −0.439 ** (−1.81) |

| Board Meeting | −0.026 *** (−2.86) | −0.016 * (−1.76) | −0.016 ** (−1.82) |

| Financial Leverage | 0.647 ** (2.04) | 0.632 ** (2.02) | 0.601 ** (1.93) |

| Constant | 4.140 *** (4.23) | 3.620 *** (6.80) | 3.852 *** (3.99) |

| R-squared | 0.0482 | 0.0732 | 0.0813 |

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSRDQ | OLS | OLS | OLS |

| PE | −0.636 *** (−4.33) | −0.514 *** (−3.52) | −0.767 *** (−5.03) |

| RB | -------------- | 0.033 *** (9.38) | 0.024 *** (6.09) |

| Interaction | -------------- | -------------- | 0.025 *** (5.37) |

| Firm Size | −0.009 (−0.21) | −0.016 (−0.37) | −0.019 (−0.44) |

| Board Size | −0.049 (−1.44) | −0.049 (−1.44) | −0.050 (−1.48) |

| Independ Direct | 0.184 ** (1.94) | 0.188 ** (2.01) | 0.180 ** (1.94) |

| Tobin’s Q | 0.056 * (−1.84) | −0.055 * (−1.82) | −0.054 ** (−1.80) |

| BTMA | −0.050 (−0.90) | −0.046 (−0.85) | −0.049 (−0.90) |

| Asset Growth | −0.176 (−1.32) | −0.016 (−0.12) | −0.078 (−0.59) |

| ROA | 0.440 (0.40) | −0.390 (−0.36) | 0.267 (0.25) |

| ROE | −0.485 ** (−1.97) | −0.440 ** (−1.81) | −0.439 ** (−1.81) |

| Board Meeting | −0.026 *** (−2.87) | −0.016 * (−1.76) | −0.016 ** (−1.82) |

| Financial Leverage | 0.647 ** (2.04) | 0.632 ** (2.02) | 0.601 ** (1.93) |

| Constant | 4.144 *** (4.24) | 3.620 *** (3.75) | 3.852 *** (4.01) |

| Lambda | 0.1235623 | 0.0275016 | 2.42827 |

| R-squared | 0.0482 | 0.0732 | 0.0813 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rauf, F.; Voinea, C.L.; Bin Azam Hashmi, H.; Fratostiteanu, C. Moderating Effect of Political Embeddedness on the Relationship between Resources Base and Quality of CSR Disclosure in China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3323. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083323

Rauf F, Voinea CL, Bin Azam Hashmi H, Fratostiteanu C. Moderating Effect of Political Embeddedness on the Relationship between Resources Base and Quality of CSR Disclosure in China. Sustainability. 2020; 12(8):3323. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083323

Chicago/Turabian StyleRauf, Fawad, Cosmina Lelia Voinea, Hammad Bin Azam Hashmi, and Cosmin Fratostiteanu. 2020. "Moderating Effect of Political Embeddedness on the Relationship between Resources Base and Quality of CSR Disclosure in China" Sustainability 12, no. 8: 3323. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083323

APA StyleRauf, F., Voinea, C. L., Bin Azam Hashmi, H., & Fratostiteanu, C. (2020). Moderating Effect of Political Embeddedness on the Relationship between Resources Base and Quality of CSR Disclosure in China. Sustainability, 12(8), 3323. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083323