Abstract

Green Care practices have received increasing scholarly attention in the last decade. Yet most studies are concerned with the aspect of human well-being, with less attention given to other caring dimensions and their relation to sustainability. This paper aims to contribute to an integrative understanding of Green Care by proposing an analytical framework inspired by the ethics of care literature and, in particular, Tronto’s five stages of caring (about, for, with, giving, and receiving). The goal is to use a relational lens to appreciate the diverse caring practices and their potential in three Finnish cases studies—a care farm, a biodynamic farm, and a nature-tourism company. We apply the framework on data gathered during three years through an in-depth participatory action-oriented research. Findings show that: (a) Green Care practitioners share sustainability concerns that go beyond human well-being and that translate into practices with benefits for the target users, wider community, and ecosystems; (b) caring is a relational achievement attained through iterative processes of learning. Two concluding insights can be inferred: a care lens sheds light on practitioners’ moral agency and its sustainability potential; in-depth creative methods are needed for a thorough and grounded investigation of human and non-human caring relations in Green Care practices.

1. Introduction

Green Care is an umbrella term used to describe a wide range of activities that contribute to different social needs through the conscious and active contact with green environments. For centuries, nature has been used in Europe to promote health and well-being [1]. Yet Green Care has emerged as a distinctive and fairly new field of study over the last 15 years, thanks in particular to EU-(co)funded research, development, and networking projects (we refer in particular to the European COST Action network 866 Green Care in Agriculture [2]). The concept of Green Care is not used consistently, however, and practices on the ground vary greatly. Examples include social and care farming, therapeutic horticulture, animal-assisted interventions, and nature-based recreation and therapy. Different aspects and priorities are pursued depending on the activity. These include health and well-being, social inclusion, and education for the personal development of particular target groups, as well as pedagogical and recreational benefits for people of all generations [3].

Two main perspectives have dominated the scientific scholarship in this field so far, focusing either on users or on providers of Green Care services. In the first instance, studies have investigated its effectiveness in contributing to well-being and social reintegration for different target groups [4,5]. The second perspective has studied Green Care as a tool for agricultural innovation and income diversification in rural areas, focusing on the entrepreneurial efforts of practitioners in diverse contexts of action [6,7,8]. Research has frequently focused on the practice of human actors looking after other people, with most attention given to human and material aspects of Green Care. Conversely, questions of cultural appreciation, community regeneration, and ecological conservation have only marginally been touched upon in Green Care literature [9,10].

Several scholars have called for additional perspectives and more integrative approaches to the field. Firstly, to check both overly critical and idealistic viewpoints in order to contribute to the scientific credibility of the field [11,12]. Secondly, to assess the benefits of Green Care that are not directly related to health, e.g., of a socioeconomic and environmental nature [12]. Thirdly, new perspectives are needed to explore the spillover effects that Green Care might have in terms of sustainable place-based development [10,11]. Notably, a recent study has considered social farming’s potential to deliver ecosystem services that sustain the management of rural landscapes [9]. Other scholars claim that direct exposure to nature and animals might trigger an enhanced care for the environment [3], or that Green Care might promote sustainable lifestyles and encourage a re-appreciation of place-based resources [8,13].

This paper aims to contribute to the debate around the sustainability impact of Green Care by unravelling the multiple care practices Green Care offers. Our goal is to elucidate the values and motives that drive Green Care, their expression in concrete practices, and the outcomes they produce. Drawing from feminist ethics of care literature and place-based approaches to development, we develop a relational approach to caring. This approach provides a lens to understand caring beyond the provision of well-being services, and, rather, as a way for people to express who they are, and who they wish to be, through everyday interactions with both the human and non-human world [14,15,16,17]. The underlying assumption is that caring practices are not only directed towards fellow human beings, but also include activities that promote social inclusion, social justice, and sustainability and are, therefore, inherently transformative [16,18].

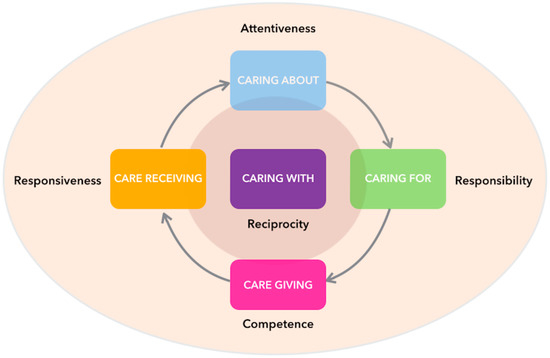

Tronto [15], a prominent figure in care ethics, distinguishes five stages and related moral principles in care: caring about (attentiveness), caring for (responsibility), care giving (competence), care receiving (responsiveness), and caring with (reciprocity). Departing from this framework, we scrutinize the care practices offered in three cases of Green Care in Finland: a care farm, a biodynamic farm, and a nature-tourism company. Our study is guided by the following research questions: (1) How can we use Tronto’s theoretical approach to develop an analytical framework that offers a more integrative understanding of Green Care practices? (2) What kind of insights does this framework reveal about the different dimensions of caring in Green Care?

With the three case studies, we also provide a deeper understanding of Green Care practices in Finland, which is a sparsely covered context in English-language literature, even though it is well advanced in many respects [8,12]. Findings stem from a process of co-production of knowledge involving research participants in successive rounds of iterative learning over the span of three years, utilizing the application of a variety of action-oriented, participatory methods. The study is part of a broader Ph.D. research project. Inspired by the tenets of place-based, transdisciplinary sustainability literature, the project aimed to engage Green Care practitioners in processes of in-depth reflection and capacity-building, shedding light on their deliberative agency, i.e., what people appreciate, feel responsible for, and are willing to commit to in the context of their own place [16,17,18]. The bulk of empirical data was gathered through semi-structured interviews with both Green Care practitioners and their networks of stakeholders. Additional data were collected through co-creation workshops, participatory mapping, participant observation, a PhotoVoice project, and a filmmaking project (see Section 4 for a detailed explanation). Data analysis was carried out through extensive qualitative coding, using a semi-grounded approach.

The next section of the paper first briefly introduces the theoretical foundation of the research, explaining why a relational approach, grounded in the ethics of care literature, can inform the study of Green Care practices. Following this, we present Tronto’s model of caring processes, the analytical framework derived from it, and its operationalization into empirical research. The third section highlights the selection of the case studies followed by a detailed explanation of the methods of data collection and analysis. In Section 4 we present the results of the analysis of empirical data. In the discussion, we reflect on what the application of our analytical framework has revealed, and what novel insights into Green Care it provides. We conclude by identifying directions for further research.

2. Towards an Ethics of Care-Inspired Approach to Green Care Practices

2.1. A Relational Approach to Green Care Practices

To make the investigation on Green Care practices more encompassing and integrative, we propose a relational approach, highlighting the web of connections and processes that enmesh people and their surroundings [16]. Feminist perspectives on the social and ecological transformations of the economy have long used relational approaches to uncover alternative possibilities [19] and bring dismissed or marginalized experiences to the fore [14]. Their contributions have affirmed the important role that care work and natural resources play in sustaining our life-supporting systems [20]. Feminist care ethicists have criticized the dominant production-oriented framing of care and nature, which assesses (and undervalues) them in utilitarian terms. Instead, they propose to depart from the connection and interdependence between the human, non-human, and more-than-human worlds [21,22,23]. (An in-depth exploration of feminist contributions to care debates and their potential to inform transformative sustainability paradigms goes beyond the scope of this paper but may be found in [18]).

At the level of the everyday, relationality and interdependence are manifested through tangible practices enacted in particular times and spaces [18]. Indeed, care is “a species activity that includes everything we do to maintain, continue, and repair our world so that we can live in it as well as possible. That world includes our bodies, ourselves, and our environment, all of which we seek to interweave in a complex, life-sustaining web” [15] (p. 19).

From an ethics of care lens, caring subjects are thus responsible humans, capable of committing to maintain and regenerate relations with a forward-looking orientation to the future: their commitment is expressed in both ethical principles and tangible doings [14]. Caring is not restricted to human interactions, but includes more-than-human subjects and non-human objects. It also goes beyond the idea of stewardship, where natural resources are something to be in charge of or to manage: rather, it understands humans as attentive members of a living web, to which needs they respond through affective and curious interactions [22,24]. (For further reading on feminist relational more-than-human thinking, see, for example, [25,26].) Thus care is not a unilateral individualistic activity, but rather an inter-activity, located between subjects [27] who shape the caring relation in a constantly ongoing process [15]. In this interaction, possibilities for change arise for the transformations of how humans relate to each other and to places, and in doing so, construct new subjectivities [18]. This raises the importance of the inner dimension of sustainability [17], the role of values, beliefs, and mindsets that determine not only the possibility to act differently, but also to wish differently.

The need to shed light on human intentionality and on subjects who enact alternative ways of relating is stressed by feminist care scholars [20,28] and by scholars investigating place-based development [8]. The latter sense an urgent need to explore how people’s engagement in place-based everyday practices produce and reflect human and non-human interactions and connections [13,16]. An ethics of care lens has already been applied to study place-based sustainability initiatives, such as permaculture [14] and Community Supported Agriculture [23], but is rarely applied to Green Care practices. Investigating Green Care practices from an ethics of care perspective will both deepen our understanding of Green Care and advance the relational turn in sustainability sciences.

2.2. An Ethics of Care Analytical Lens to Study Green Care Practices

Following the model outlined by Tronto [15], caring is expressed in two ways: by means of ethical principles and through embodied practices. She captured this duality in the five stages of the caring process, with each stage represented by a practice that is motivated and activated by a moral principle. A visual representation of the five stages is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Five stages of caring and related moral principles. Inspired by Tronto (2013).

The caring process starts with caring about, fueled by the principle of attentiveness. Caring involves “attentive communicative contact” [27] (p.119), the capacity to notice unmet needs around us, suspending self-interest, and adopting the perspective of others. The possibility of caring is not only limited to what is close to us or to our next of kin, but also to strangers and distant others. Recognizing mutuality can activate this internal state of readiness to care about. The recognition of unmet needs may lead to the second stage in the caring process, caring for. Attention may become intention—to act upon those needs—which eventually coalesces into action [24]. This stage is triggered by a feeling of responsibility. Within the ethics of care, responsibility is not seen as an obligation, or as the ex-post accountability for what has been done. Rather, it is the result of a practice of relationality, and thus can be best framed in terms of response-ability: the more we engage in relations, the more we feel both responsible and able to respond to the needs previously noticed [18]. The third stage involves the actual work of care, care giving. Care work is not just a technical exercise, but rather a moral practice requiring competence. To make sense of the mutual reciprocal relationship established between the two sides of the caring spectrum, Tronto adds two more stages. Care receiving is the fourth one, animated by the value of responsiveness, which presupposes that those being cared for are entitled to respond to the care given, commenting on its quality and effectiveness. Through this process, new needs may be acknowledged, after which the care process continues and a new care cycle begins. However, not all care receivers may be able to respond, as the care process can be asymmetrical in nature. Tronto, therefore, includes caring with as the fifth stage, encompassing the entire care process. Care practices should be designed and implemented in such a way that recognizes care receivers’ dignity and knowledge, and, additionally, creates the necessary conditions for empowerment through processes of learning that may benefit all [1,29]. Several principles align with this stage, including plurality, communication, trust, and respect, which Tronto summarizes with the concept of solidarity. Another value underlined in the ethics of care literature is reciprocity. This alludes to the mutually beneficial relationship made possible by an attitude of attentiveness, respect, and solidarity, and recognizes care receivers as active agents in the caring process. Moreover, it implies that caring needs and practices must be consistent with democratic commitments to justice, equality, and freedom for all [15]. Indeed, caring is not a process confined to the walls of a therapeutic space. It is rather a transparent process of learning and empowerment that may trigger virtuous spillover effects for society at large and benefit other caregivers and care receivers over time [29].

Two other studies applied Tronto’s framework to Green Care, a theoretical reflection by Barnes [1] and a study by Hassink et al. [30] (to which the first author of this paper is a contributor). Yet neither of the two studies engages with all five stages of caring or investigates Green Care practices or practitioners’ experiences in depth, leaving the analytical potential of Tronto’s framework rather unexplored. This study aims to survey this potential more fully by operationalizing Tronto’s theoretical approach into an analytical framework for the study of Green Care practices (Research Question no. 1). We do so by deriving a set of guiding questions for each stage in the caring process. They are empirical questions that will help us to explore which new insights into the multidimensionality of Green Care this framework generates (Research Question no. 2). This, in turn, will allow us to evaluate the usefulness of the conceptual framework. The empirical questions are presented in Table 1 and summarized below.

Table 1.

An ethics of care-inspired analytical framework for Green Care practices.

The stage of caring about precedes the actual practice of Green Care and corresponds to the concerns and reasons, at both societal and personal levels, that practitioners express when motivating their desire to engage in Green Care practices. Hence, we ask what Green Care practitioners are attentive to, and what concerns motivate their actions. The stage of caring for relates to the actual Green Care activities, best exemplified in what practitioners do on a daily basis—both for target users and for the larger community and ecosystem—to respond to concerns and motivations identified in the previous stage. The following stage of care giving points at the how, namely the specific ways in which practices are carried out, looking at core ingredients, criteria, and ways of working. The fourth stage, care receiving, deals with the concept of responsiveness and can be addressed by investigating what mechanisms are in place for care receivers to respond to the practices of care. The final stage in Tronto’s model, caring with, is underpinned by the principle of solidarity or reciprocity. With reference to Green Care, we believe reciprocity best expresses the value and practice of establishing empowering learning processes beneficial for both sides of the caring spectrum and, possibly, for society at large. Thus we ask how principles of reciprocity and mutual learning are expressed throughout the entire process of caring.

3. Methods of Data Collection and Analysis

3.1. Selection of Case Studies

In Finland, the concept and practice of Green Care has gained rapid popularity since its introduction in mid-2000. Since then, advocacy and capacity-building efforts (i.e., training, communication, and networking) have been pursued via roughly 90 regional projects, aimed especially at developing the services, and their classification and quality standards.

With the support of the Green Care Finland Association [31], which has been gathering practitioners and researchers in the field since 2010, attempts have been made to classify the range of existing activities, and to facilitate their institutionalization [32]. The process has come to favor a rather broad understanding of the concept of Green Care, inclusive of a variety of different nature-based services. Since 2017, practitioners can apply for a process of certification to obtain a quality mark in either one of the two typologies that currently qualify as Green Care practices: (1) Nature Care (Luontohoiva), referring to a number of services mainly financed by the public sector, provided by health and social care professionals, and targeted at vulnerable groups; (2) Nature Empowerment (Luontovoima), including goal-oriented services in nature-assisted well-being, education, and recreation, often purchased by private users [33].

Research in Finland, as well as elsewhere, is still in its infancy: more studies are needed to explore the ways in which practices are delivered, and to identify the institutional and cultural barriers and carriers that can facilitate its development as a cross-sectoral innovation [8,32].

This study features three diverse cases of Green Care in Finland, representative of both Nature Care and Nature Empowerment typologies, which were selected after several visits to different Green Care practices located in southern and central Finland. In the end, a care farm, a biodynamic farm, and a nature-tourism company were chosen as cases for this study. The selection of case study sites was informed by our wish to include different sectors—namely, farming and tourism—that comprise very diverse activities. The cases are also at different stages of certification towards obtaining the quality mark. At the same time, all three of the case studies are small ventures, with the core management in the hands of family members and with the funders engaged in the care practices. There were also more pragmatic reasons. The practitioners could communicate fluently in English, were interested in being part of the research project, and their locations were accessible by public transport. Below we provide a brief description of the three cases. More detailed information is presented in the Results section and as Appendix A (Table A1).

The care farm is located 25 km away from the city of Tampere and engages a group of around 15 mentally disabled customers in both husbandry and farming practices. It provides health and social care services in partnerships with local municipalities. One of the two founders coordinates all the operations on the farm, which is supported by a highly specialized staff, knowledgeable in nursing and social care, as well as animal husbandry and gardening. The farm has recently obtained the Nature Care quality mark.

The biodynamic farm sells organic vegetables to nearby schools and restaurants, at the outskirts of the Helsinki metropolitan area. Over the years, it has hosted projects aimed at social inclusion and work reintegration of long-term unemployed people, funded by the local municipality and a non-profit association. It also regularly engages in pedagogical activities. Its practitioners have not applied for any formal certification so far, but are involved in long-term plans to build a care home for elderly people on the farm in the future.

Finally, the nature-tourism company, based in the city of Tampere, has offered a wide range of services to private customers on nearby lakes and in forests for 25 years. Activities include rental and training services for outdoor sports, team-building and recreational programs, and, to a lesser extent, therapeutic activities. The company was one of the first in Finland to obtain the Nature Empowerment quality mark. The company’s main founder was engaged in advocacy and development work in the early years of the Green Care Finland Association.

3.2. Methods of Data Collection

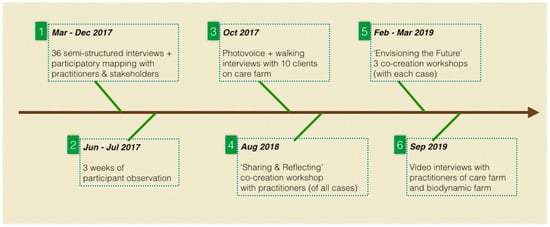

The empirical work of this study is based on in-depth qualitative research carried out during three years of continuous engagement with the three enterprises, as portrayed in Figure 2. The engagement formed part of a Ph.D. research project informed by place-based, transdisciplinary sustainability science, enriched by the principles and techniques of Participatory Action-Research [13,34,35]. In line with these traditions, the collaboration aimed at not only gathering relevant data, but also at fostering a process of critical reflection and capacity-building in collaboration with the people involved, appreciating assets and capacities rather than focusing on problems and deficiencies [28,35]. To achieve these goals, all methods were designed and implemented following principles such as inclusiveness, transparency, reflexivity, and empathy.

Figure 2.

Stages of data collection and related methods.

In the first stage of fieldwork, a total of 36 semi-structured interviews were used to gather in-depth information about each case, along with participatory mapping exercises that supported the process of reflection. Interview respondents included the founders and main practitioners of the three cases and their core staff (14 people). These conversations proved extremely valuable to get a thorough understanding of how Green Care practitioners make sense of what they do. Participants were not directly asked about issues of care. Rather, they were stimulated to talk about their daily activities and interactions, as well as to reflect on the development of both their practices and their places, tapping into past experiences and future aspirations. Particular importance was given to their perceptions, values, and emotional involvement with both humans and non-humans. To gather multiple perspectives on each Green Care case, it was deemed useful to combine such accounts with additional perspectives from outside collaborators. To this aim, the founders of each enterprise were asked to list a number of external stakeholders whom they had been in close contact with over the previous years. These included 32 people, among which local civil servants, employees in the research and education sector, private enterprises, and social organizations who concurred to either the provision or use of the Green Care services in question. In the end, 22 people accepted to be interviewed.

Additionally, one entire week per case study was dedicated to participant observation, in order to engage first-hand with participants’ real-life contexts, observing the interactions of people and their environments, and looking at practices performed in places. The same year, a group of ten men with mental disabilities, working and living on the care farm, were involved through the use of PhotoVoice, a method particularly suited to engage vulnerable individuals in explaining their reality using photos as visual aids [36]. Photos served as prompts to discuss what customers both value and dislike about their daily routine on the farm, in order to give voice to their experiences as care receivers.

After 18 months of research the main practitioners of the three case studies (nine people) were involved in the first co-creation workshop, called Sharing and Reflecting. In the spirit of iterative mutual learning, the workshop served to present and discuss the preliminary results and conceptual frameworks of the research—including Tronto’s five stages of caring. Participants’ reflections validated and enriched the researchers’ interpretations of the data. During the workshop, visual materials were used to facilitate the discussions and arts-based techniques helped to foster inclusive team-building and invite lateral thinking around the issues at stake [34,35].

In the Spring of 2019, three more co-creation workshops, called Envisioning the Future, were organized to support practitioners in elaborating long-term visions about the development of their practices and places. During the workshops, a variety of analytical techniques and visual materials—inspired by system thinking and design thinking—were employed to map both present realities and future possibilities. Moreover, visioning arts-based techniques were used to invite participants to tap into their sustainability mindsets, embracing perspectives of both humans, non-humans, and more-than-humans, when imagining the future of their places [37].

Finally, additional data was gathered during a filmmaking project that involved only two of the three cases for dissemination purposes. Five practitioners were interviewed again during the process, and asked to focus on the societal value of their practices and places and to reflect on benefits and challenges of being part of participatory research.

Figure 3 provides a visual documentation of some of the methods described above.

Figure 3.

Methods of data collection. From left to right: Semi-structured interview and participatory mapping; Sharing and Reflecting workshop; participant observation; Envisioning the Future workshop.

3.3. Methods of Data Analysis

Transcriptions of the data were analyzed with the help of ATLAS.ti, while departing from a semi-grounded theory approach. In the first round of analysis, only the semi-structured interviews were considered. The transcriptions were coded using three overarching frames: diagnostic, prognostic, and motivational frames. Although somehow complementary and overlapping with Tronto’s model of caring, they were considered useful to unpack the interviewee’s cognitive process of individual sense-making, while maintaining a more neutral approach to the data (less influenced by the theoretical framework). Diagnostic frames were used to trace the causality of the problem, in this case they were the societal issues that participants would refer to when motivating their involvement with Green Care practices. Prognostic frames revealed what actions were done to solve the problems identified. Motivational frames highlighted the rhetorical schemas and inspirational discourses that people would use to explain the value and rationale of their practices.

Following this, the literature was reviewed once again, and the analytical framework was revised and refined based on the insights gained during the first round of coding. In the second round of analysis, all text (both from the interviews and from the other phases of data collection) was inserted into ATLAS.ti. In this phase of coding we used the five analytical questions derived from Tronto’s model. This allowed a more articulated and detailed picture of the various dimensions of caring.

4. Results: Towards a Comprehensive Understanding of Green Care Practices

This section presents the findings from our analysis applying Tronto´s five stages of caring (see Figure 4). The findings are organized for semantic coherence, using the analytical framework as guidance, and are presented accordingly with the observed patterns that emerged from the data analysis. We make ample use of quotations to give a vivid account of the everyday experiences and their significance. These quotations are placed within brackets, indicating the source (with P standing for practitioner, S for external stakeholder, and C for the disabled customers involved in the PhotoVoice project) and method used (Int. stands for semi-structured interview; V-Int. for Video interview; Sha-workshop for Sharing and Reflecting co-creation workshop; Fut-workshop for the Envisioning the Future co-creation workshops; Photo for PhotoVoice). The full list of research participants, divided per case study, is provided as Appendix A in Table A2. (All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Wageningen School of Social Sciences).

Figure 4.

Empirical findings: Green Care practices across five stages of caring.

4.1. Care about: What Are Green Care Practitioners Attentive to? What Are the Concerns They Care about?

The initial stage of the caring process is when unmet needs around us are noticed, suspending self-interest and adopting the perspectives of others. Our sample of Green Care practitioners is attentive to a variety of societal and personal issues, concerning four main areas: social inclusion, human–nature disconnection, urban–rural disconnection, and aspirations and passions.

Social inclusion is a common concern across all practitioners. In the care farm, the commonly-accepted portrayal of disabled people as a monolithic group is of particular concern, as it fails to appreciate the individual’s diverse needs, capacities, and aspirations (Int. P11). This resonates with the biodynamic farm practitioners’ assertion that a variety of audiences should be included: “It’s somewhere in our principles to welcome everyone, regardless the background or abilities” (V-Int. P19). Attention to vulnerable groups is also key to the work of the nature-tourism company, but is framed as guaranteeing everyman’s right to nature regardless of age, physical conditions, or other factors (Int. P1, P3). In fact, this right is institutionalized in the Finnish law, which enables everyone to access and enjoy outdoor pursuits with few restrictions [38].

Secondly, most practitioners express deep preoccupation with the human–nature disconnection that results, in their view, from an increasingly urbanized model of socioeconomic development (Int. P1, P13, P19). In particular, they fear that future generations may lack the ability to “know” and “understand” natural ecosystems and the possibilities they offer (Int. P1, P3, P11). They also refer to the detrimental effect on human well-being that such disconnection yields (Int. P18): “If you don’t understand the nature, and if you don’t want to protect it, and if you only want to consume, for yourself, we, mankind, won’t exist very long” (Int. P1).

For the practitioners of the two farms, these concerns are closely related to their worry about urban–rural disconnection and the consequences that emerge from it, such as food illiteracy and loss of traditional rural landscapes. “I would like people to notice the difference in how you can farm, how it affects the quality, and how important the social aspect is, that people have a connection with the surroundings and the goods they consume,” stated one practitioner (V-Int. P18). Providers often point at society’s inability to recognize the mutual relationship of urban and rural areas, and the cultural loss this causes (Int. P11; V-Int. P17): “We are trying to nourish the landscape and keep this surroundings inhabited so that it’s also some kind of cultural landscape, like a rural landscape, and you lose that if you don’t have grazing animals. And if you don’t care about the nature, it will disappear” (V-Int. P11).

As far as the personal sphere is concerned, the professional pathways of all practitioners are geared towards the realization of personal nature-related aspirations and passions. The founders of the care farm said that they were able to realize their long-standing dream of living on a farm by way of the Green Care practices as they gave enough financial stability to maintain the place (Int. P10, P11). As one of them confessed, “This is not a 9–5 type of work. It’s actually not a work, it’s a way of life” (V-Int. P11). Love for animals, for countryside environments, and for community building, is shared by the whole staff at the care farm (Int. P12, P13, P14). In the biodynamic farm, the practice of Green Care provides an avenue to express anthroposophical principles valued by practitioners, as well as their efforts to “save the farm” from urban development projects (Int. P17) within the Helsinki metropolitan area, which could transform the area into a residential neighborhood. Finally, in the case of the nature-tourism company, both main practitioners and their staff are passionate about outdoors and nature sports, and longed for challenging, versatile, and meaningful jobs (Int. P1, P2, P3, P4).

4.2. Care for: How Are Practitioners Able to Respond to Those Needs and Concerns? What They Do and for Whom?

In Tronto’s model, attentiveness translates into action in the phase of caring for. Ideally, people are now ready to respond to needs of care through tangible practices. Data collected show how practitioners act upon their concerns through a variety of practices.

Social inclusion is pursued in different ways. The care farm fulfills this need via the main Green Care services it provides: structured therapeutic and well-being interventions offered to a group of mentally disabled people. These include on-farm working tasks and an assisted living unit that permanently hosts two thirds of their customers. Moreover, the farm has launched a special project called mobile unit, which allows some participants to be involved in simple voluntary chores in the neighboring villages. This project has two goals: to better meet the needs of clients who cannot sustain a regular daily routine, and to connect the farm with the wider community, while also breaking down preconceptions about disabled people (Int. P11). In the biodynamic farm, social inclusion is fostered by welcoming people from all walks of life, including marginalized individuals, to live and work temporarily on the farm. This is done via both the WWOOF (World Wide Opportunities on Organic Farms) program and informal connections (Fut-workshop). Past ad-hoc Green Care projects were aimed at including vulnerable groups (e.g., long-term unemployed), with professional caretakers hired to look after the participants. Furthermore, children with special needs have been visiting the farm for annual pedagogical activities. In the case of the nature-tourism company, attention to social inclusion is expressed in their commitment to design outdoor sports equipment for disabled customers in collaboration with a local NGO (Int. S6, S7). Moreover, their service package includes guided tours for severely disabled people—in partnership with a local transportation company specialized in this field—as well as visits to elderly care homes (Int. S11, S12).

To respond to concerns for human–nature disconnection, all of the three cases engage in pedagogical and recreational activities. This is mostly evident in the nature-tourism company, as the leisure and learning components of all activities take place in natural environments. In addition, the company is regularly hired to provide trainings, mostly for university students and firms’ employees, so that they “can find their own way into nature” (Int. P1, P3). The underlying idea is that by experiencing joy and self-efficacy in forests and lakes, the desire to access and care for those places will flourish (Int. P1, P5). Moreover, there is a strong commitment among the owners and the staff of the company to increase safety awareness among amateurs practicing outdoor sports, by providing accurate information about the conditions of ice, water, wind, etc., through their social media channels on a daily basis. This helps to attract potential customers and at the same time is perceived by practitioners as integral to their ethical commitment to defy “fake news” and to guarantee wide access to nature all year long (Fut-workshop). Both farms are also very active in pedagogical activities and participate in the training of students, teaching of school children, and organizing recreational events for wider audiences. Moreover, the biodynamic farm, through the WWOOF program, offers several groups of volunteers the opportunity to learn farm work while being part of a community and a safe inclusive space: “The thing that I like the most is the reconnection of people, they have a direct contact with the surroundings and they find that they can make a difference, ... they can build their own world, and be a part of it” (Int. P18). With regards to future plans, practitioners would like to strengthen and enlarge all the activities concerned with human well-being, recreation, and learning. Moreover, they hope to nurture ecosystem well-being and the flourishing of multispecies. In fact, especially for the farms, the two things are often envisioned as complementary and equally necessary (Fut-workshop).

This leads to the concern about rural–urban disconnection, which is addressed in the daily activities on both farms. At the moment, food production guarantees most of the income for the biodynamic farm, via gardening and animal husbandry (used for manure only). Vegetables are sold to local restaurants and schools, and at a self-service on-farm shop. Moreover, for several years, the farm owner has been negotiating with the local municipality to preserve the land from urban development. The hope is to maintain the core farming activities while expanding caring, recreational, pedagogical, and residential opportunities (Fut-workshop). In the case of the care farm, gardening is mostly done for self-consumption and to ensure healthy diets for the farm inhabitants. Sheep are mostly raised for grazing and, to a lesser extent, for local lamb production: when meat is sold, buyers are invited to come to the farm to see where and how it is produced (Int. P13, S16). Moreover, practitioners periodically visit local schools to talk about rural livelihoods, particularly sheep shearing and wool-making practices (Int. P11). Finally, both farms are engaged in landscape maintenance and preservation—with special attention to traditional Finnish customs and aesthetics—as well as to biodiversity conservation and regeneration. As stated by one practitioner: “We have put a lot of effort and work to create this place as it is now, so that’s why there is this special relationship with this place” (Int. P10). The manual and affective work of place-shaping is constant, and makes both farms unique beautiful environments for both insiders and outsiders (Int. P11, P18, S2, S16).

All the above mentioned activities speak to the personal nature-related aspirations and passions of practitioners. Indeed, services are designed and provided according not only to the values and concerns listed above, but also with an attention to market demands. Personal interests and the skills of the staff are also crucial in shaping the provision of services in all three cases (Int. P3, P4, P6, P12, P18).

External stakeholders are often unaware of the variety of activities practitioners engage with. Moreover, they mostly value the well-being aspects of the services offered in the three enterprises, and give less importance to other caring dimensions, such as the pedagogical and environmental ones (Int. S5, S11, S21, S15).

4.3. Care Giving: How Are Practices Implemented on an Everyday Basis?

This question is concerned with the specific ways in which practices are implemented, along with what Tronto refers to as competence, encompassing both technical skills and the moral behavior underlying the work of caring [15]. Two patterns emerge from our data in this respect: (a) a core set of basic ingredients needed to provide good quality Green Care services; (b) a shared list of criteria and ways of working.

4.3.1. Key Ingredients

Data reveal that the most important ingredient in Green Care is to be fully present in nature. “Experiencing nature,” “feeling nature,” “connecting to nature,” and “caring about the environment” are recurrent mottos employed by practitioners and stakeholders across all cases. Natural elements are seen as not only triggering positive sensorial and neurological experiences, but also generating sentiments of worthiness and empowerment. Caring for the animals is a core dimension of this process, a phenomenon that was highlighted by the customers working in the care farm (Photo. C2, C4, C6, C7, C10). Engaging with wilderness is deemed equally important: “Nature, the forest, it accepts you as you are,” said one practitioner at the biodynamic farm (V-Int. P19). The latter element emerged even more clearly in the case of the nature-tourism company, whose core mission is to ensure access to nature. “Bringing people close to nature” by practicing outdoor sports in peri-urban natural spaces and protected areas is often mentioned by the respondents (Int. P1, S12). In all three cases, the environments where caring activities take place reflect Finnish culture and traditions. Both of the farms are small scale, yet they are intrinsically diverse and well cared for, with a particular attention given to maintaining traditional buildings and small infrastructures. The salience of this aesthetic element features strongly in the data: beauty and harmony are recurrent themes in both practitioners’ and stakeholders’ accounts (Int. P10, P12, P18, P19, S2). For the nature-tourism company, the uniqueness of Finnish forests and lakes is a source of identity and pride, and something to share with others “with joy” (Int. P1, P3, S4).

A second core ingredient emerging from the data is togetherness, fostered through team-building and collaboration (Int. P1, P3, P10, P13). In the care farm, inclusiveness and a sense of belonging are attained by making sure that “everyone has their own meaningful role in it, and can get a feeling of worth[iness] and of being a purposeful part of this community” (V-Int. P10). Similarly, for many the biodynamic farm represents a home, a safe place of belonging (Int. P17, P19, S22): “People have come from quite different backgrounds and they meet each other here and are like a family, eating and working together” (V-Int. P17). External stakeholders share the same feeling about both places (Int. S2, S16, S20, S21, S23). In the case of the nature-tourism company, togetherness is pursued by mixing up conventional roles and creating an atmosphere of equality. This allows group bonding while appreciating different capabilities (Int. P1, P2).

A third crucial ingredient is to engage in meaningful work and experiences. For the farms, this means carrying out tangible tasks that are useful for the farms and/or the surrounding communities (Int. P10, P11, P18, P19, S13, S16, S21). This “real” work is valued by many among the mentally disabled customers in the care farm, both because it allows them to grasp the usefulness of their work, and because it enables them to employ and strengthen competences gained through previous education (Photo. C1, C5, C7, C9, C10). In the case of the nature-tourism company, a meaningful experience implies physical exercise, as no equipment powered by motors is used. To be deemed meaningful, experiences must be “unique” and “memorable” (Int. P5, P6, S3, S8, S9), and they should enliven the senses and generate feelings of joy, fun, and peace (Int. P1, P3, P5, P18, S4, S10).

4.3.2. Criteria and Ways of Working

Care practices are never accomplished once and for all, as care work needs to be constantly attuned to the needs and capacities of those involved [39]. All of the case studies demonstrate a human-oriented approach, which goes beyond a customer-oriented one, as it is driven by a desire to enable customers’ capabilities and to do more than just satisfying their demands (Fut-workshops). Flexibility is inherent in this way of working—something that both the care farm and nature-tourism company are well-known for (Int. P1; P12; S5; S16). As stated by one practitioner, “We want to provide the best possible care and working methods, to suit each and every individual” (V-Int. P11). The biodynamic farm also offers a variety of activities to ensure that “everyone can find something they are able to do” (Int. P19). A human-oriented approach goes hand in hand with the idea of slowness. Indeed, caregiving often implies that priority is given to a deep engagement with both humans and non-humans rather than efficiency: “When trying to be very efficient, someone is paying for it, with too high a price, maybe the environment, or the people” (V-Int. P19).

While valuing flexibility, practitioners design and implement interventions with a conscious rationale and method, namely a goal-oriented approach (Int. P10, P18). This is enabled by the high-level expertise of practitioners and their staff, most evident in the care farm and nature-tourism company (Int. P1, P2, P4, S4, S10, S14): “We have a workforce that varies in profession and in background and everybody brings in their know-how, and that’s how the common capabilities and resources are formed” (V-Int. S10). According to interviewees, a vast array of skillsets is also found on the biodynamic farm, but more professional figures might be needed if the site scales up its Green Care service provision (Int. S19, S20, S22, S23). Professionalism is often coupled with passion and “working with the heart,” something deeply valued by stakeholders and an identity trait of all practitioners (Int. P11, S5; Sha-workshop).

All the above are complemented by a deep sense of responsibility towards those involved. Practitioners are aware of the importance of guaranteeing participants’ well-being and safety at all times (Int. P4, P5, P13, P17, P19, S13). This includes avoiding contact with poisonous plants, and using animals that are of mild temperament and of reasonable size. Apart from human safety, respect for nature ecosystems and for the well-being of plants and animals is very evident in practitioners’ narratives. In the case of the farms, this is guaranteed by adhering to organic and biodynamic values and standards (Int. P13, P17, P19), including reducing animals’ stress and suffering, and practicing gratitude, as evidenced by the following quote: “We should appreciate their offer, and, if we have to take the life from the sheep, that is our responsibility to utilize the maximum amount of it” (Int. P11).

For the nature-tourism company, respect for nature includes learning how to be in contact with the elements, understanding one’s own limits, and enhancing one’s own resourcefulness. Finally, practitioners explain the importance of contemplation and relationality, for instance, by inviting customers to pause and listen to the sounds of the forest during a guided visit (Int. P3, P4).

4.4. Care Receiving: What Mechanisms Are in Place for Care Receivers to Respond to the Practices of Care?

Tronto’s model endorses the idea that the practice of caring is not a matter of giving something to others who may passively receive it. On the contrary, a lot of care work is actually done by care receivers [39]. Based on this premise, guaranteeing participants’ responsiveness is key for practitioners to ensure that needs are identified and acknowledged throughout the care cycle [14]. In our data, the role of responsiveness emerged along three main patterns: design, assessment, and adaptation (these aspects are foundational of iterative learning processes [40]).

As far as design is concerned, care farms choose and prioritize tasks based on the daily needs of the farm (Int. P10, P13). This is organized with an appreciation for each participant’s skills and capabilities, and leaves room for deliberation, negotiation, and tinkering (Int. P13, P14). Other aspects of daily life are also discussed, such as weekly diets, hobbies, and social activities. In the biodynamic farm, where participants are not engaged in the long-term operations of the farm, there is less opportunity for the co-evolution and co-creation of roles and skills. Yet practitioners are equally attentive to individuals’ capabilities and wishes (Int. P18, S21). As far as the nature-tourism company is concerned, services are proposed to customers and are adapted as per the requirement of the demand. During the activities, special attention is given to each person’s capability, based on informal conversation and observation (Int. P2, S4).

In terms of assessment, the care farm has a variety of mechanisms in place to gather feedback on the quality and effectiveness of the care given. Practitioners patiently observe participants, getting constant feedback from them. Moreover, every day before lunch, a short “daily talk” takes place, during which participants are free to share feelings, preferences, and thoughts with their supervisors (Int. P11, P13). Further feedback is provided by the network of stakeholders, in particular by customers’ families, who often comment on the progress of their dear ones (Int. P11). Social workers responsible for these individuals at municipality level are engaged in the weekly communications to monitor each person’s well-being. Finally, formal evaluations on the progress of each participant are carried out yearly and compiled in reports filed by the social workers (Int. P10). The biodynamic farm relies on more informal channels to gather feedback, including attentive observation and exchanges of views during lunch time (Int. P17, P19). When ad-hoc programs with vulnerable groups were implemented, the funding agencies administered final surveys to the participants (Int. S2). The staff at the nature-tourism company, for example, seeks feedback through the observation of participants during the activities. Questionnaires were administered in some cases, in collaboration with local health institutes, to gather data on the well-being effects of nature-based interventions. Moreover, customers give feedback on social media applications such as Trip Advisor and the like (Int. P1, P4).

Finally, practitioners explained that constant assessment is useful for adaptation. Through the feedback gathered, they can adapt and modify the design of the practices. This aspect features particularly strongly in the case of the care farm, perhaps as a result of a more structured goal-oriented approach to caregiving and of the specific needs of its customers (Int. P1, P11, P18).

4.5. Caring with: How Are Principles of Reciprocity and Mutual Learning Expressed through the Process of Caring?

An approach to reciprocity, as explained in the theoretical part, entails that both sides of the caring spectrum are considered dignified agents in the caring process. It includes processes of learning that are beneficial for the caring relation itself as well as society at large [29].

Upon examining the three cases, it is easily observed that the idea of learning is deeply engrained in practitioners’ mindsets and methods. Learning is described as something essential from various points of view. Firstly, it is crucial in the empowerment and capacity-building process of care receivers. One practitioner said: “I always try to give a good experience to customers, making them learn in a good mood, and making them enjoy the nature so much that they would come back to it” (Int. P3). Learning is crucial in customers’ personal development: it encompasses acquiring new skills, understanding the purpose behind daily operations (Int. P13, P14), and gaining a sense of worth for the work done: “The need to feel that we are important and that we are doing something with meaning is mandatory to all of us” (Int. P10).

Secondly, learning is essential for practitioners’ own pathways of progress and improvement as care providers: “We are learning on the way, and all the time gaining more trust among the clients” (Int. P10); “We have learnt a lot. We have not become rich economically, but in experiences” (Int. P1). It is also useful as it triggers the processes of innovation needed to sustain the enterprise in the long term: “The world around you is constantly changing, and if you are not able to follow the change, you found some day that you are obsolete” (Int. P11).

For practitioners, learning and reciprocity are deeply intertwined: “You want to give a lot to the people who participate, so the people give to the farm, and it becomes this give and take relationship” (Int. P19); “We really benefited from these exchanges of ideas. Meeting different people and talking with them, it’s been really essential for the farm” (Int. P17). Learning and reciprocity are often practiced beyond day-to-day operations, through educational activities open to the wider community and more or less spontaneous ways of knowledge sharing: welcoming visitors and prospective Green Care entrepreneurs on the farm or engaging in advocacy and networking activities with other practitioners in the field. Motivation for this project was also taken from the desire of practitioners to advance the field of Green Care in Finland in ways that could be beneficial for society at large (Int. P1, P10, P17).

Another element worth noting is that reciprocity permeates relations with non-human beings. Indeed, care flows from practitioners to human participants, but at the same time both practitioners and participants care for animals and for the soil and forest resources, etc. Equally, such nature elements indirectly care for and with both participants and practitioners, as expressed in these quotes: “Actually I don’t have to do much, because the nature is some kind of caretaker itself” (Int. P2). In both farms, non-human elements are recognized as sentient and are cared for respecting their natural cycles. Despite lack of verbal communication, reciprocity in the caring relation is expressed in other ways: “That’s one of the biggest things, people appreciating their surroundings, and the fruits of their work. And that’s where it all starts, you get an immediate feedback from the surroundings” (V-Int. P18); “It’s always nice to see the interaction between our customers and the animals, this kind of communication without words. You can see there is something that I cannot explain” (Int. P11).

Interpreting the data, we found that reciprocity is also expressed in practitioners’ recognition of the interdependence of human and ecosystem well-being. One of the founders of the care farm stated: “We try to see this not just as a farm, not just as a place where we take care of people. It’s a combination, where everything is related to each other” (V-Int. P11). A different perspective on interdependence is given by the founder of the nature-tourism company: “I want to bring nature close to people, so I do it by telling stories. I tell about how people moved to Finland, how they were dependent from nature, and somehow I want to make people understand that we are still dependent from that” (Int. P1). This aspect distinguishes practitioners’ and stakeholders’ accounts. The latter recognize the importance of respecting ecosystems, but still see non-human living beings and natural environments as much less central in Green Care in comparison to human beings, sometimes naming them as “partners” in the caring process (Int. S23, S11) and other times naming them merely as “resources” instrumental to a goal (Int. S5, S22).

5. Discussion: Towards an Integrative Framework to Understand Green Care Practices

In this section, we respond to the research questions and present some general conclusions and reflections, with regards to our contribution to the study of Green Care practices and their sustainability potential, and to the scientific debates around the ethics of care and place-based development.

As summarized in Figure 4 (see Section 4), our analytical investigation across Tronto’s five stages of caring has revealed the following findings: (1) Practitioners are attentive to several issues that go beyond human health and well-being. They care about social inclusion, not only as the empowerment of vulnerable groups, but also as societal access to green environments. They are concerned about human–nature disconnection and, in particular, the two farms fear urban–rural disconnection. Finally, they are all passionate about working in a green environment and protecting nature. (2) Their attentiveness to such concerns and needs manifests itself in the daily practices they engage in and which go beyond the services they are most known for by their networks of stakeholders. They actually include a wealth of “invisible” activities (Fut-workshops), such as community building and outreach, awareness-raising, education and training, biodiversity regeneration, and appreciation of local traditions and livelihoods. Such activities are not exclusively directed to their target users; rather, they are rooted in context-dependent collective interests, tied to the needs of the places in which they are embedded, and thus benefit both the wider community and ecosystem. (3) Practitioners’ commitment to heal, empower, and regenerate people through practices of caring is not only expressed in what they do, but also how they do it. Core ingredients of high quality Green Care services appear to be nature, togetherness, and meaningful work and experiences. Human- and goal-oriented approaches characterize the ways of working, following criteria of flexibility, slowness, professionalism, responsibility, safety, and respect. (4) Both providers and customers of care activities are considered and respected as active agents. Practices are characterized by deliberation and tinkering. This is possible by designing services in a way that fits the capacities and aspirations of participants, implementing formal and informal mechanisms of assessment of the practices, and being open to constant adaptation. (5) The data reveal that learning is an essential element in all three cases. Green Care practitioners value learning deeply, for themselves as persons and professionals and for those they engage with. In the spirit of reciprocity, processes of learning also include the wider community beyond the target users. Reciprocity is a trait of human and non-human relations in these Green Care practices. Practitioners value the interdependence of human and ecosystem well-being and recognize non-human beings as sentient participants in the caring process.

Our findings align with recent literature pointing at the wider potential of Green Care practices, not only for the provision of well-being services, but also as engagement for sustainability oriented towards the conservation and regeneration of the living basis of socio-ecological systems [9,11]. Yet, such potential seems to go mostly undetected by the wider networks of stakeholders, who, depending on the specific relation and interests that connect them to one or other Green Care practice, are unaware of and/or unconcerned about the bigger picture. The Envisioning the Future workshops revealed how the practitioners themselves may even underestimate the full spectrum of care dimensions they engage with daily. The workshops were crucial to unveil the variety of practices, both visible and invisible, raising awareness of the value and scope of their work for both people and ecosystems. Based on the findings of this study, our understanding is that wider awareness of the reality and potential of Green Care practices in Finland needs to be fostered at all levels: on the ground, working with providers to gain a deeper and broader outlook on what they do and how; in the way associations and research centers frame their advocacy, development, and assessment efforts; and at policy levels, for decision-makers to be able to regulate the field of Green Care in ways that valorize and maximize this hidden potential.

The value of Tronto’s model lies in the new insights its application has generated. Firstly, looking into the first two phases of caring about and caring for allowed us to shed light on the interaction between practitioners’ caring concerns and the practices enacted to meet them. This provides further evidence of humans’ willingness to engage with the betterment of the world, as proposed by both the feminist ethics of care literature and place-based development scholarship [16,17,18]. Indeed, the practitioners in our cases are not just service providers but moral agents who, through curious attention to the needs of others, express their sense of self and community through the responsibilities they discover and claim as theirs. What they wish and what they do reflect a plurality of care(s) that is directed to both human and non-human worlds, and that shapes their identities and subjectivities. The entire framework, and especially the phase of care giving, allowed us to see that moral values are an integral part of how practitioners implement their practices. In line with feminist literature on caring, ethics function as a compass that guides people’s choices of who to be, what to think, and how to bring principles into action through embodied practices [23,28].

Secondly, applying Tronto’s framework on the field of Green Care practices confirmed that caring is not merely about a succession of health interventions, to be monitored and evaluated quantitatively [5]. Interventions go hand in hand and are sustained by the relational work that often goes unnoticed, as care scholars have suggested in the past [21,39]. Caring itself is a relational achievement involving all sides of the caring spectrum: practitioners, human participants, and more-than-human elements. From an analytical point of view, the stages of care receiving and caring with are particularly crucial in this sense, as they force us to go beyond care giving as a unilateral doing. Rather, they stress the need to see caring as a process based on reciprocity, mutual deliberation, and learning [29].

Thirdly, Tronto’s framework invites us to see caring as a cycle. Its iterative, interconnected nature is itself conducive to constant learning and improvement, ideally enabling virtuous changes to happen. Transformations happen not only in the here and now of the caring process; rather, they extend to long-term temporalities and wider scopes of impact. One example is given by the work of caring for the soil in the biodynamic farm: the experience can lead to instant feelings of well-being and self-efficacy for the participants involved. In the long run, such slow and attentive work of caring is also beneficial to regenerate the soil and its living beings, which in turn gives healthy and nutritious fruits to the wider community purchasing the food. The transformative value of learning through caring practices is a perspective still very marginal in studies of place-based practices such as Green Care, which deserves further investigation.

Yet Tronto’s framework has analytical limitations. The five stages of caring, when applied to Green Care practices, may lead to anthropocentric considerations. Indeed, the role of non-human agency was harder to detect when interrogating the data. Further application of this framework could benefit from the integration of other bodies of knowledge, both theoretical and applied, that have looked at the role of non-human and more-than-human agency in various fields, expanding epistemological assumptions to include new ways of knowing. We refer in particular to more-than-human anthropology and ethnography [25], post-human environmental ethics [26,41], and action-oriented approaches to more-than-human research [42,43,44]. To take account of more-than-human agency requires the development of new methods, as conventional methodological approaches are biased towards a human-centered outlook. This is especially true when non-human and more-than-human elements are not the main focus of the research, as in the case presented here. Indeed, the importance of the methods emerged over the course of the investigation. During the Envisioning the Future co-creation workshop the researcher-facilitator used arts-based techniques to evoke regenerative ecological mindsets (see for instance [37]) to sensitize the participants to more-than-human and non-human components. Scholarship on Green Care, which still mostly relies on interviews and surveys [12], could greatly benefit from the integration of arts-based and creative methodological tools.

6. Conclusions

Narrow understandings of Green Care practices hinder the possibility to recognize their full potential for place-based sustainability. This study has attempted to develop an integrative framework to study Green Care practices, employing a relational approach inspired by the feminist ethics of care literature and Tronto’s five stages of caring. The framework was applied to three diverse cases of Green Care in Finland. It revealed that practitioners share a plurality of care concerns that are strongly connected to sustainability and translate into tangible practices that go beyond human health and well-being. These practices benefit the target users, wider community, and ecosystems. Our findings point to the importance of not just observing, but also appreciating Green Care practitioners’ sense of moral agency, and to further investigating the potential it yields for developing just, inclusive, and regenerative societies.

Our study highlights the value of multi-case and multi-method approaches for the study of Green Care. By involving practitioners, target users, and wider networks of stakeholders, we obtained a diversity of views and identified the mismatches in how practices are framed. In turn, this shows the need to provide in-depth, systemic outlooks of Green Care practices to advocates, developers, and policy-makers in the field.

The analytical framework proposed in this paper should not be viewed as having hard, definitive boundaries. Additional interpretations are needed to fully explore and test its relevance in other contexts of Green Care. Moreover, the use of creative techniques proved effective in highlighting the role of more-than-humans in the caring process, but further methodological perspectives are needed to fully comprehend how practices are done in, for, and with nature.

Author Contributions

Paper conceptualization—A.M., K.S., B.B.B., D.R.; data collection and analysis—A.M.; methodology—A.M.; writing—A.M.; review and commentary—B.B.B., K.S., D.R.; data visualization—A.M.; project supervision—K.S., D.R.; funding acquisition—D.R., A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie Grant Agreement No. 674962. Additional support has been provided via a personal working grant funded by Kone Foundation, project identification no. 201801752.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all the participants that took part in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Full list of activities offered by the case studies.

Table A1.

Full list of activities offered by the case studies.

| CARE FARM | BIODYNAMIC FARM | NATURE-TOURISM COMPANY |

|---|---|---|

| WELL-BEING and SOCIAL INCLUSION | WELL-BEING and SOCIAL INCLUSION | WELL-BEING and SOCIAL INCLUSION |

| All year-round health and social care interventions + rehabilitative work for disabled people; Assisted Living Unit on farm | Ad-hoc temporary projects of rehabilitative work for long-time unemployed groups. | Recreation and well-being activities for various groups (children; tourists; people with disabilities; elderly in care homes). |

| PEDAGOGY and RECREATION | PEDAGOGY and RECREATION | PEDAGOGY and RECREATION |

| Traineeships for students; Trainings for prospective care farmers; Educational activities in local schools about rural livelihoods; Recreational activities for larger audiences (open days; festivals, etc.) | Hosting of different individuals through WWOOF program; Engagement of pupils of local Steiner and Waldorf schools and kindergartens; Traineeships for students through BINGN network and through local collaborations; Recreational activities for larger audiences (open days; festivals, etc.) | Traineeships for university students; Outdoors team-building activities for companies’ employees; Outdoors sports trainings for various groups; Rental services of outdoors sports equipment. |

| OUTREACH | OUTREACH | OUTREACH |

| Community services with mobile unit; Ongoing reception of people interested in care farming. | Grassroots advocacy to build a future community on the farm; Affordable living spaces on farm for long or temporary stays. | Daily accurate information provision about weather conditions (e.g., ice thickness) available to wide audience through social media. |

| AGRICULTURE and ECOSYSTEM | AGRICULTURE and ECOSYSTEM | ADDITIONAL SERVICES |

| Sheep husbandry (and organic meat sales to local networks); Animal care (pigs, dogs; horses; chickens; rabbits; cats); Organic gardening for self-consumption; Rural landscape preservation and maintenance; Biodiversity conservation and regeneration. | Cow husbandry (for biodynamic farming); Animal care (chickens; cats); Organic vegetables production for local purchase (restaurants, markets, schools in Helsinki area + on-farm shop); Rural landscape preservation and maintenance; Biodiversity conservation and regeneration. | Product design and manufacturing (including special equipment for disabled people); Catering and logistics for other companies; Snacks and drinks purchase at company’s premises. |

Table A2.

Full list of research participants.

Table A2.

Full list of research participants.

| List of practitioners | ||||||

| Case | Reference code | Practitioner’s role | Interview (date) | Sharing workshop | Future workshop | Video interview |

| Nature-tourism company | P1 | founder of company, retired | 05.03.2017 | x | x | |

| P2 | owner of company, manager | 04.06.2017 | x | |||

| P3 | staff, also involved in management | 01.04.2017 | x | x | ||

| P4 | staff, also involved in management | 01.04.2017 | ||||

| P5 | staff | 11.07.2017 | ||||

| P6 | staff | 11.07.2017 | ||||

| P7 | staff | x | ||||

| P8 | staff | x | ||||

| P9 | staff | x | ||||

| Care farm | P10 | owner and manager of farm | 08.06.2017 | x | x | x |

| P11 | owner and manager of farm | 06.06.2017 | x | x | ||

| P12 | staff | 06.07.2017 | ||||

| P13 | staff | 07.07.2017 | x | |||

| P14 | staff | 20.10.2017 | x | |||

| P15 | staff | x | x | |||

| P16 | staff | x | ||||

| Biodynamic farm | P17 | farm owner | 07.03.2017 | x | x | x |

| P18 | farm manager | 30.03.2017 | x | x | x | |

| P19 | farm community member | 31.03.2017 | x | x | x | |

| List of external stakeholders | ||||||

| Case | Reference Code | Field of activity | Interview (date) | Future Workshop | ||

| Nature-tourism company | S1 | Education and Research | 18.09.2017 | |||

| S2 | NGO | 22.09.2017 | ||||

| S3 | Education and Research | 12.10.2017 | ||||

| S4 | Private business | 13.10.2017 | ||||

| S5 | Education | 13.10.2017 | ||||

| S6 | NGO | 13.10.2017 | ||||

| S7 | NGO | 13.10.2017 | ||||

| S8 | Private business | 25.10.2017 | ||||

| S9 | Private business | 25.10.2017 | ||||

| S10 | Local government | 25.10.2017 | ||||

| S11 | Private business | 13.12.2017 | ||||

| S12 | Private business | 13.12.2017 | ||||

| Care farm | S13 | Education and Research | 14.09.2017 | |||

| S15 | Local government | 18.10.2017 | ||||

| S16 | Local government | 19.10.2017 | ||||

| S17 | Health and social care sector | x | ||||

| S18 | Education sector | x | ||||

| Biodynamic farm | S19 | Education | 08.09.2017 | |||

| S20 | Local government | 10.10.2017 | ||||

| S21 | NGO | 11.10.2017 | ||||

| S22 | Local government | 03.11.2017 | ||||

| S23 | Local government | 10.11.2017 | ||||

| S24 | NGO | 14.11.2017 | ||||

| S25 | Self-sufficient farmer | 16.11.2017 | ||||

| List of customers involved in the PhotoVoice project | ||||||

| Case | Reference Code | PhotoVoice and walking interview (date) | ||||

| Care farm | C1 | 16.10.2017 | ||||

| C2 | 16.10.2017 | |||||

| C3 | 16.10.2017 | |||||

| C4 | 16.10.2017 | |||||

| C5 | 17.10.2017 | |||||

| C6 | 17.10.2017 | |||||

| C7 | 17.10.2017 | |||||

| C8 | 19.10.2017 | |||||

| C9 | 19.10.2017 | |||||

| C10 | 19.10.2017 | |||||

References

- Barnes, M. Care, deliberation and social justice. In Proceedings of the Community of practice Farming for Health, Ghent, Belgium, 6–9 November 2007; Dessein, J., Ed.; ILVO: Merelbeke, Belgium, 2008; pp. 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Green Care in Agriculture. Health Effects, Economics, and Policies. Available online: https://www.cost.eu/publications/green-care-in-agriculture-health-effects-economics-and-policies/ (accessed on 10 April 2020).

- Sempik, J.; Hine, R.; Wilcox, D. Green Care: A Conceptual Framework. A Report of the Working Group on the Health Benefits of Green Care, COST Action 866, Green Care in Agriculture; Centre for Child and Family Research, Loughborough University: Loughborough, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rappe, E. The Influence of A Green Environment and Horticultural Activities on the Subjective Well-Being of the Elderly Living in Long-Term Care; University of Helsinki: Helsinki, Finland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Elsey, H.; Bragg, R.; Elings, M.; Cade, J.E.; Brennan, C.; Farragher, T.; Tubeuf, S.; Gold, R.; Shickle, D.; Wickramasekera, N.; et al. Understanding the impacts of care farms on health and well-being of disadvantaged populations: A protocol of the Evaluating Community Orders (ECO) pilot study. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e006536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassink, J.; Grin, J.; Hulsink, W. Multifunctional agriculture meets health care: Applying the multi-level transition sciences perspective to care farming in the Netherlands. Sociol. Ruralis 2013, 53, 223–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessein, J.; Bock, B.B.; De Krom, M.P.M.M. Investigating the limits of multifunctional agriculture as the dominant frame for Green Care in agriculture in Flanders and the Netherlands. J. Rural Stud. 2013, 32, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriggi, A. Exploring enabling resources for place-based social entrepreneurship. A participatory study of Green Care practices in Finland. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 15, 437–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Llorente, M.; Rossignoli, C.; Di Iacovo, F.; Moruzzo, R. Social farming in the promotion of social-ecological sustainability in rural and periurban areas. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guirado, C.; Valldeperas, N.; Tulla, A.F.; Sendra, L.; Badia, A.; Evard, C.; Cebollada, À.; Espluga, J.; Pallarès, I.; Vera, A. Social farming in Catalonia: Rural local development, employment opportunities and empowerment for people at risk of social exclusion. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 56, 180–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Iacovo, F.; Moruzzo, R.; Rossignoli, C.M.; Scarpellini, P. Measuring the effects of transdisciplinary research: The case of a social farming project. Futures 2016, 75, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Llorente, M.; Rubio-Olivar, R.; Gutierrez-Briceño, I. Farming for life quality and sustainability: A literature review of green care research trends in Europe. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horlings, L.G.; Roep, D.; Mathijs, E.; Marsden, T. Exploring the transformative capacity of place-shaping practices. Sustain. Sci. 2020, 15, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puig de la Bellacasa, M. Ethical doings in naturecultures. Ethics Place Environ. 2010, 13, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tronto, J.C. Caring Democracy: Markets, Equality, and Justice; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tschakert, P.; St.Clair, A.L. Condition for transformative change: The role of responsibility, care, and place-making in climate change research. In Proceedings of the International Conference “Transformation in a Changing Climate, Oslo, Norway, 19–21 June 2013; pp. 267–275. [Google Scholar]

- Horlings, L. Values in place; A value-oriented approach toward sustainable place-shaping. Reg. Stud. Reg. Sci. 2015, 2, 257–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriggi, A.; Soini, K.; Franklin, A.; Roep, D. A care-based approach to transformative change: Ethically-informed practices, relational response-ability, & emotional awareness. Ethics Policy Environ. 2020. Accepted. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson-Graham, J.K. The End of Capitalism (As We Knew It). A Feminist Critique of Political Economy; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MI, USA; London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Schildberg, C. A caring and sustainable economy: A concept note from a feminist perspective. Int. Policy Anal. 2014, 1–13. [Google Scholar]