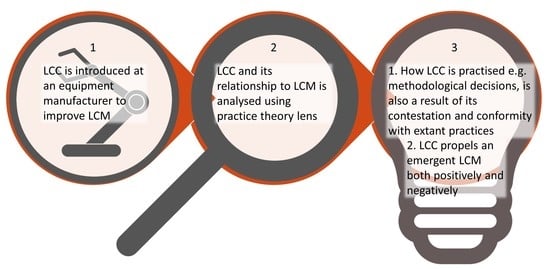

Life Cycle Costing: Understanding How It Is Practised and Its Relationship to Life Cycle Management—A Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. A Brief Overview of Practice Theory and Its Elements

2.2. Life Cycle Costing

2.3. Life Cycle Management as a Practice and Its Relation to Life Cycle Costing

2.4. Product-Service Systems as a Practice

3. Method

3.1. Method Overview

3.2. Case Company and Background for Introducing LCC

- Understand in detail the change in the cost structure and cost drivers between PSS and business-as-usual;

- Compare the LCC for various offerings for the same or for different customers;

- Identify uncertainties;

- Identify additional ways of using LCC to improve LCM.

3.3. Data Collection and Analysis

3.3.1. The Role of the Researcher

3.3.2. Documents

3.3.3. Interviews, Focus Groups, Activities, and Dissemination Seminars

4. Results on Contestation and Conformity between LCC Practice and Extant Practices

4.1. Body of the Individual

4.2. Mind of the Individual

4.3. Objects—Material and Symbolic

“this is not how we slice the cake… trying to allocate these costs (sales and customer costs) to products will be more effort than doing the LCC”.(I19)

4.4. Collective Knowledge

4.5. Discourse—A Common Denominator

4.6. Individuals—The Role of R&D Engineers

4.7. Structure and Processes

4.8. Discussion

5. Life Cycle Costing’s Relationship to Life Cycle Management

5.1. Life Cycle Costing propelling Life Cycle Management

5.1.1. Background

First, both parties aim at carrying out research with world-class scientific quality contributing to global competitiveness of the Swedish manufacturing industry. The second aim is to enhance the contribution to each party’s education (…). The third aim is to contribute to society both on the regional and national scales in terms of economic growth, job creation, and environmental sustainability.

5.1.2. Desired Propulsion

5.1.3. Undesired Propulsion

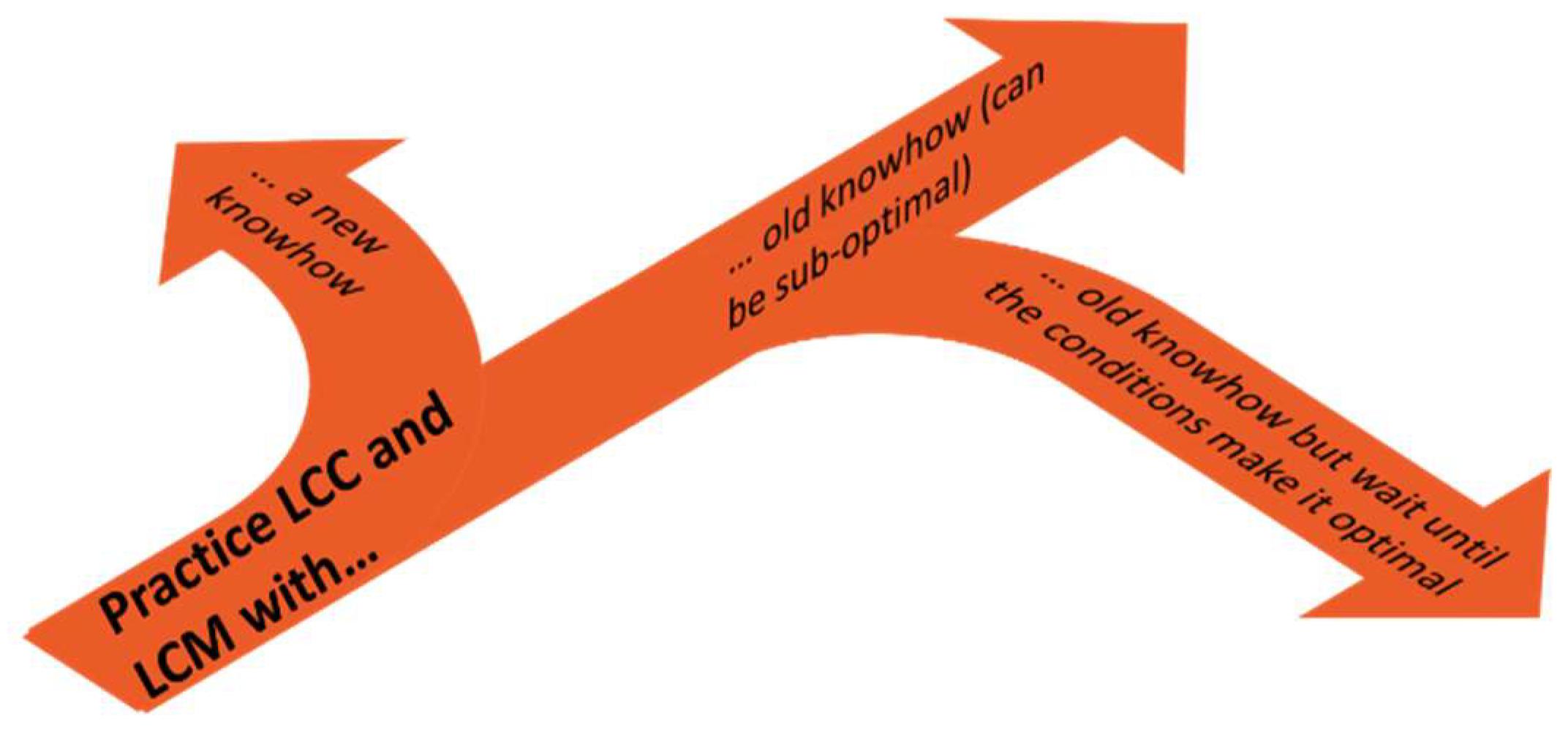

5.2. Life Cycle Costing, Life Cycle Management, and Other Practices

6. Concluding Discussion

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

6.2. Managerial Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Commission, B. Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- De Haes, H.A.U.; van Rooijen, M. Life Cycle Approaches: The Road from Analysis to Practice; UNEP/SETAC Life Cycle Initiative: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Westkämper, E.; Alting; Arndt. Life Cycle Management and Assessment: Approaches and Visions Towards Sustainable Manufacturing. Cirp Ann. 2000, 49, 501–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bey, N. Life Cycle Management. In Life Cycle Assessment: Theory and Practice; Hauschild, M., Rosenbaum, R.K., Olsen, S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rebitzer, G.; Hunkeler, D. Life cycle costing in LCM: Ambitions, opportunities, and limitations. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2003, 8, 253–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluch, P.; Gustafsson, M.; Baumann, H.; Lindahl, G. From tool-making to tool-using–and back: Rationales for adoption and use of LCC. Int. J. Strateg. Prop. Manag. 2018, 22, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpi, E.; Ala-Risku, T. Life cycle costing: A review of published case studies. Manag. Audit. J. 2008, 23, 240–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higham, A.; Fortune, C.; James, H. Life cycle costing: Evaluating its use in UK practice. Struct. Surv. 2015, 33, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Incognito, M.; Costantino, N.; Migliaccio, G.C. Actors and barriers to the adoption of LCC and LCA techniques in the built environment. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2015, 5, 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opoku, A. The application of whole life costing in the UK construction industry: Benefits and Barriers. Int. J. Archit. Eng. Constr. 2013, 2, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochschorner, E.; Noring, M. Practitioners’ use of life cycle costing with environmental costs—A Swedish study. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2011, 16, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reckwitz, A. Toward a Theory of Social Practices:A Development in Culturalist Theorizing. Eur. J. Soc. Theory 2002, 5, 243–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schatzki, T.R. Social Practices: A Wittgensteinian Approach to Human Activity and the Social; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolini, D. Practice Theory, Work, and Organization: An Introduction; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, M.S.; Orlikowski, W.J. Theorizing Practice and Practicing Theory. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 1240–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronholm, S.; Goldkuhl, G. Actable Information Systems—Quality Ideals Put Into Practice. In Proceedings of the Eleventh Conference On Information Systems Development (ISD 2002), Riga, Latvia, 12–14 September 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lounsbury, M.; Crumley, E.T. New Practice Creation: An Institutional Perspective on Innovation. Organ. Stud. 2007, 28, 993–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palo, T.; Åkesson, M.; Löfberg, N. Servitization as business model contestation: A practice approach. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 486–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunkeler, D.; Lichtenvort, K.; Rebitzer, G. Environmental Life Cycle Costing; Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry (SETAC): Pensacola, FL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Neugebauer, S.; Forin, S.; Finkbeiner, M. From Life Cycle Costing to Economic Life Cycle Assessment—Introducing an Economic Impact Pathway. Sustainability 2016, 8, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, B.H.; Sun, Y. The development of life-cycle costing for buildings. Build. Res. Inf. 2016, 44, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson-Lindén, H.; Diedrich, A.; Baumann, H. Life Cycle Work: A Process Study of the Emergence and Performance of Life Cycle Practice. Organ. Environ. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, K. Social Practices: A New Focus Area in LCM. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Life Cycle Management, Gothenburg, Sweden, 25–28 August 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Seidel-Sterzik, H.; McLaren, S.; Garnevska, E. A Capability Maturity Model for Life Cycle Management at the Industry Sector Level. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolini, D. Zooming In and Out: Studying Practices by Switching Theoretical Lenses and Trailing Connections. Organ. Stud. 2009, 30, 1391–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldkuhl, G. The research practice of practice research: Theorizing and situational inquiry. Syst. Signs Actions 2011, 5, 7–29. [Google Scholar]

- Czarniawska, B. On Time, Space, and Action Nets. Organization 2004, 11, 773–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, K.; Czarniawska, B. Knotting the action net, or organizing between organizations. Scand. J. Manag. 2006, 22, 292–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiedu, Y.; Gu, P. Product life cycle cost analysis: State of the art review. Int. J. Prod. Res. 1998, 36, 883–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC. Dependability Management—Part 3-3: Application Guide—Life Cycle Costing, 3rd ed.; International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Settanni, E.; Newnes, L.B.; Thenent, N.E.; Parry, G.; Goh, Y.M. A through-life costing methodology for use in product–service-systems. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 153, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogmartens, R.; Van Passel, S.; Van Acker, K.; Dubois, M. Bridging the gap between LCA, LCC and CBA as sustainability assessment tools. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2014, 48, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, R.; Jawahir, I.S.; Badurdeen, F.; Rouch, K. A total life cycle cost model (TLCCM) for the circular economy and its application to post-recovery resource allocation. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 135, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, A.E.; Pezzotta, G.; Pinto, R.; Romero, D. A comprehensive description of the Product-Service Systems’ cost estimation process: An integrative review. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2019, 221, 107481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, V.; Weidema, B.P. The computational structure of environmental life cycle costing. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2015, 20, 1359–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Giacomo, M.R.; Testa, F.; Iraldo, F.; Formentini, M. Does Green Public Procurement lead to Life Cycle Costing (LCC) adoption? J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2019, 25, 100500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, J. Product Lifecycle Management: 21st Century Paradigm for Product Realisation, 2nd ed.; Springer: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Remmen, A.; Jensen, A.A.; Frydendal, J. Life Cycle Management: A Business Guide to Sustainability; UNEP/Earthprint: Nairobi, Kenya, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bierer, A.; Götze, U.; Meynerts, L.; Sygulla, R. Integrating life cycle costing and life cycle assessment using extended material flow cost accounting. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 108, 1289–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluch, P.; Baumann, H. The life cycle costing (LCC) approach: A conceptual discussion of its usefulness for environmental decision-making. Build. Environ. 2004, 39, 571–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehm, M.; Thomas, O. Looking beyond the rim of one’s teacup: A multidisciplinary literature review of Product-Service Systems in Information Systems, Business Management, and Engineering & Design. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 51, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukker, A. Product services for a resource-efficient and circular economy—A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 97, 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, H.; Roy, R.; Seliger, G. Industrial Product-Service Systems—IPS 2. Cirp Ann. 2010, 59, 607–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matschewsky, J.; Kambanou, M.L.; Sakao, T. Designing and providing integrated productservice systems—Challenges, opportunities and solutions resulting from prescriptive approaches in two industrial companies. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2017, 56, 2150–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, V.; Bastl, M.; Kingston, J.; Evans, S. Challenges in transforming manufacturing organisations into product-service providers. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2010, 21, 449–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagoropoulos, A. Product/Service-Systems in the Maritime Industry—From Economic Evaluation Throughout the Life Cycle to Implementation; Technical University of Denmark: Lingbi, Denmark, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kohtamäki, M.; Baines, T.; Rabetino, R.; Bigdeli, A.Z. Practices in Servitization. In Practices and Tools for Servitization; Kohtamäki, M., Baines, T., Rabetino, R., Bigdeli, A.Z., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew, A.M. Longitudinal Field Research on Change: Theory and Practice. Organ. Sci. 1990, 1, 267–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building Theories from Case Study Research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Given, L.M. The Sage Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods; SAGE Online: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Schwandt, T.A. The Sage Dictionary of Qualitative Inquiry; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, U. An Introduction to Qualitative Research; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Baumann, H.; Tillman, A.-M. The Hitchhiker’s Guide to LCA: An Orientation in Life Cycle Assessment Methodology and Application; Studentlitteratur: Lund, Sweden, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl, M.; Sundin, E.; Sakao, T. Environmental and economic benefits of Integrated Product Service Offerings quantified with real business cases. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 64, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassanelli, C.; Rosa, P.; Rocca, R.; Terzi, S. Circular economy performance assessment methods: A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 440–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, M.; Germani, M.; Zamagni, A. Review of ecodesign methods and tools. Barriers and strategies for an effective implementation in industrial companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 129, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasinski, D.; Meredith, J.; Kirwan, K. A comprehensive review of full cost accounting methods and their applicability to the automotive industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 108, 1123–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelakoglou, K.; Gaidajis, G. A review of methods contributing to the assessment of the environmental sustainability of industrial systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 108, 725–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodward, D.G. Life cycle costing—Theory, information acquisition and application. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 1997, 15, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Date | Participants | No Part. | Type | Id |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| May 2015 | Project group | 5 | Start-up—Scope setting | G1 |

| June 2015 | PSS and Remanufacturing | 1 | Scope setting | I1 |

| October 2015 | Services | 2 | Data collection | G2 |

| October 2015 | PSS and Remanufacturing | 1 | Scope setting | I2 |

| November 2015 | PSS and Remanufacturing | 1 | Scope setting | I3 |

| November 2015 | PSS and Remanufacturing | 1 | Scope setting | I4 |

| November2015 | Services | 1 | Data collection | I5 |

| December 2015 | Sales and customer service | 1 | Scope setting | I6 |

| January 2016 | Product Management | 1 | Goal setting | I7 |

| January 2016 | R&D | 1 | Goal setting | I8 |

| January 2016 | PSS and Remanufacturing | 1 | Intermediate result discussion | I9 |

| January 2016 | Sales and customer service | 1 | Scope setting | I10 |

| February 2016 | Services | 1 | Data collection | I11 |

| February 2016 | PSS and Remanufacturing | 1 | Intermediate result discussion | I12 |

| March 2016 | Services | 1 | Data collection | I13 |

| March 2016 | PSS and Remanufacturing | 1 | Informational interview | I14 |

| March 2016 | Project group | 5 | Focus group—cost estimation techniques | G3 |

| March 2016 | Sales and customer service | 1 | Informational interview | I15 |

| March 2016 | Services | 1 | Data collection | I16 |

| April 2016 | Production | 1 | Data collection | I17 |

| April 2016 | Transport | 1 | Data collection | I18 |

| April 2016 | Sales and customer service | 1 | Informational interview | I19 |

| April 2016 | Sales and customer service | 1 | Informational interview | I20 |

| April 2016 | Services | 1 | Data collection | I21 |

| April 2016 | Sales and customer service | 1 | Informational interview | I22 |

| May 2016 | R&D | 1 | Information collection | I23 |

| May 2016 | Services | 1 | 1st round result discussion | I24 |

| May 2016 | Project group | 6 | Focus group—1st round result discussion | G4 |

| May 2016 | Services | 1 | 1st round result discussion | I25 |

| June 2016 | R&D | 1 | 1st round result discussion | I26 |

| August 2016 | Sales and customer service | 1 | 1st round result discussion | I27 |

| March 2017 | Services | 1 | Adjustments to costing techniques | I28 |

| April 2017 | Sales and customer service | 1 | Adjustments to costing techniques | I29 |

| April 2017 | R&D | 1 | Adjustments to costing techniques | I30 |

| June 2017 | Sales and customer service | 1 | Informational interview | I31 |

| June 2017 | Accounting | 1 | Informational interview | I32 |

| June 2017 | Sales and customer service | 1 | Informational interview | I33 |

| June 2017 | Accounting | 1 | Informational interview | I34 |

| November 2017 | Project group | 6 | Final result presentation and focus group on recommendations | G5 |

| November 2017 | Focus group | 8 | Final result presentation and focus group on recommendations | G6 |

| December 2018 | Top Management | 3 | Final result presentation and focus group on recommendations | G7 |

| January 2018 | Top management | 10 | Dissemination | G8 |

| May 2018 | Middle management company wide | 18 | Dissemination and discussion about findings—future | G9 |

| May 2018 | Middle management company | 14 | Dissemination and discussion about findings—future | G10 |

| Findings | Considerations for LCC method development | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | LCC is tailored based on the outcome of its contestation and conformity with extant practices | Limit flexibility of LCC method on key issues. (especially important if LCC is used for LCM) |

| 2 | LCC is an emergent practice | Include different LCC stages or levels that a company advances to over time |

| 3 | LCC becomes practice through repetition | 1. Engage individuals repetitively during the LCC process 2. Disseminate intermediary LCC results |

| 5 | Individuals practice LCC differently influenced by the extant practices they perform | 1. Include individuals from across the lifecycle 2. Clearly define key concepts e.g. lifecycle 3. Carefully match appropriate individuals to LCC activities 4. Carefully consider how extant practices might constrain an individual from following the LCC method |

| 6 | For traditional product-manufactures the “product” is in the centre | Emphasize the service aspect and provide detailed advice on how to include it |

| 7 | The perception of the “company” constrains the lifecycle perspective | Clearly define key concepts e.g. lifecycle |

| 8 | Reports and presentations of results are important objects for reproducing LCC practice | 1. Emphasize wide dissemination of results 2. Include opportunities for cross-departmental discourse about results |

| 9 | Demonstrating plurality of the lifecycle supports a deeper understanding of the lifecycle | 1. Do not encourage generic LCC cost models 2. Use sensitivity analysis |

| 10 | Limitations of using precise data when conducting LCC | 1. Explain potential data limitations 2. Provide good examples of companies who have successfully used LCC despite data limitations |

| 11 | Limitations of using extant costing methods when conducting LCC e.g. “book value” vs “market value” | 1. Explain current costing methods’ limitations 2. Suggest relevant costing methods |

| 12 | Common words are ascribed diverging meanings | Clearly define key concepts e.g. lifecycle |

| 13 | Discussions are crucial to making methodological decisions for LCC | Include discursive activities |

| 14 | R&D engineers have capabilities to perform LCC | Include R&D engineers if relevant |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kambanou, M.L. Life Cycle Costing: Understanding How It Is Practised and Its Relationship to Life Cycle Management—A Case Study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3252. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083252

Kambanou ML. Life Cycle Costing: Understanding How It Is Practised and Its Relationship to Life Cycle Management—A Case Study. Sustainability. 2020; 12(8):3252. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083252

Chicago/Turabian StyleKambanou, Marianna Lena. 2020. "Life Cycle Costing: Understanding How It Is Practised and Its Relationship to Life Cycle Management—A Case Study" Sustainability 12, no. 8: 3252. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083252

APA StyleKambanou, M. L. (2020). Life Cycle Costing: Understanding How It Is Practised and Its Relationship to Life Cycle Management—A Case Study. Sustainability, 12(8), 3252. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083252