Fostering Generative Partnerships in an Inclusive Business Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Generative Partnerships in an Inclusive Social Ecosystem

2.1. Generative Partnerships

2.2. An Inclusive Social Ecosystem

3. Methods

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Case Selection

3.3. Data Sources

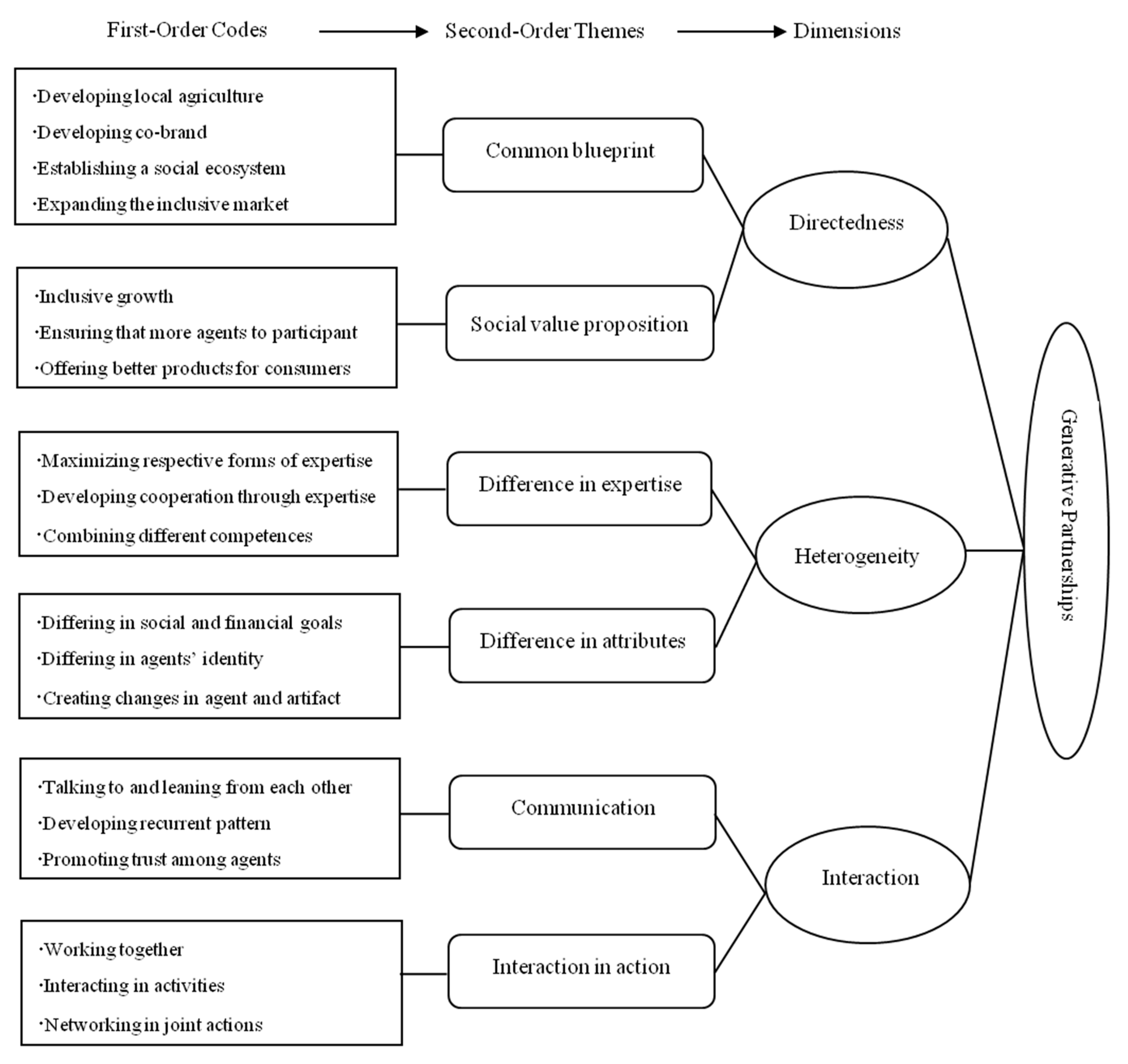

3.4. Data Analysis

4. An Inclusive Business Model of Ecosystem Creation

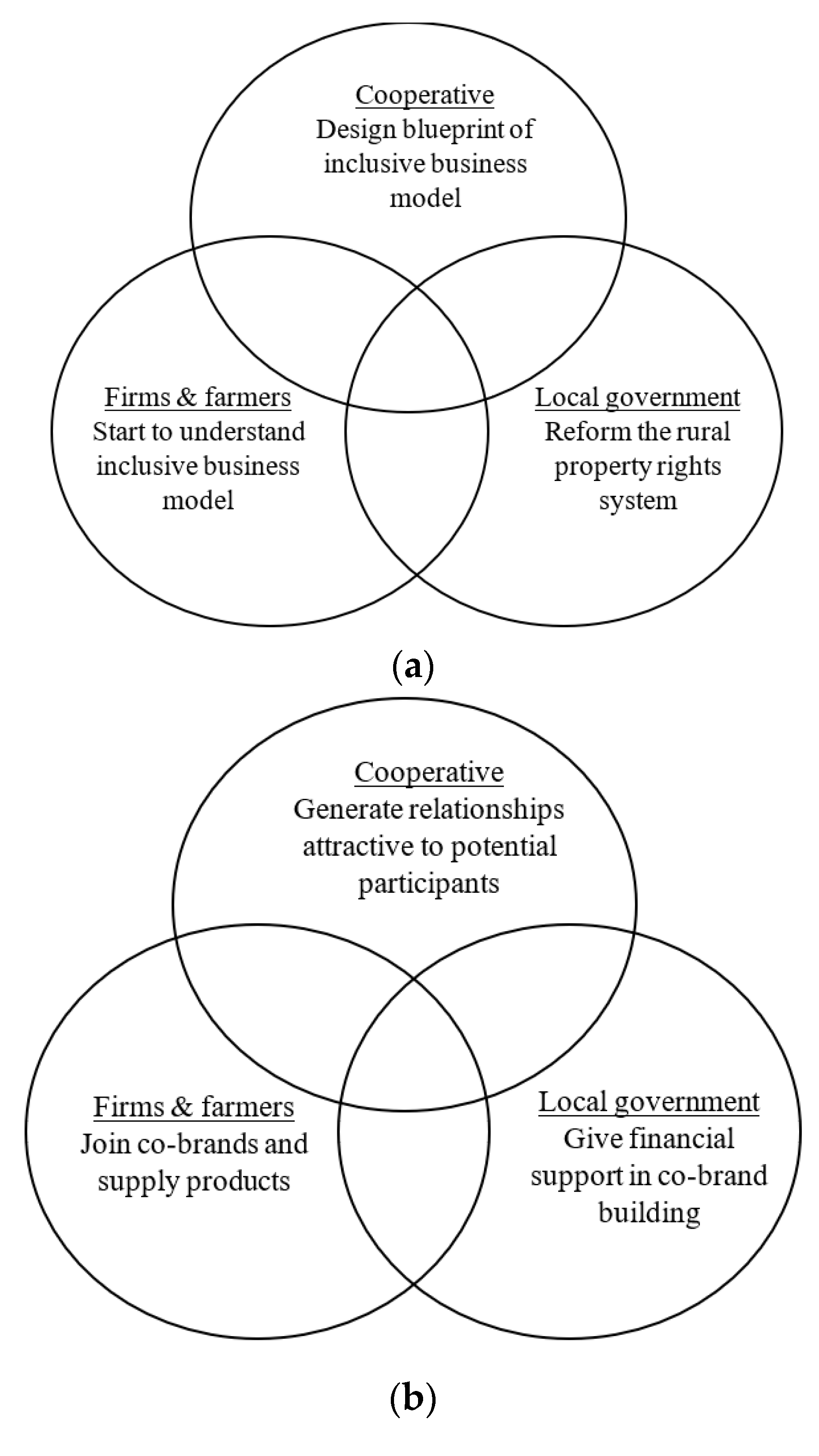

4.1. The First Stage: Value Blueprint

4.2. The Second Stage: Pilot Demonstration

4.3. The Third Stage: Scaling-up

4.4. The Fourth Stage: Snowballing—Developing a Hybrid Network

4.5. Two Schemas Institutionalizing Hybrid Partnerships

5. Discussion

5.1. Findings

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Piketty, T.; Goldhammer, A. The Economics of Inequality; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Stiglitz, J.E. The Price of Inequality: How Today’s Divided Society Endangers Our Future; Norton: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Krugman, P. The Conscience of a Liberal; Norton: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gelles, D.; Yaffe-Bellany, D. Shareholder Value is no Longer Everything, Top C.E.O.s Say; Bus. Sect.; The New York Times: New York, NY, USA, 19 August 2019. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP. Creating Value for All: Strategies for Doing Business with the Poor; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Silver, H. Social exclusion and social solidarity: Three paradigms. Int. Labour Rev. 1994, 133, 531–578. [Google Scholar]

- Prahalad, C.K. The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid: Eradicating Poverty through Profits; Wharton School Publishing: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, J.; Matos, S.; Sheehan, L.; Silvestre, B. Entrepreneurship and innovation at the base of the pyramid: A recipe for inclusive growth or social exclusion? J. Manag. Stud. 2012, 49, 785–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradl, C.; Knobloch, C. Inclusive Business Guide: How to Develop Business and Fight Poverty; Endeva: Berlin, Germany, 2010; Available online: https://endeva.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/IBG_final.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2020).

- Christensen, C.M.; Ojomo, E.; Dillon, K. The Prosperity Paradox: How Innovation Can Lift Nations out of Poverty; HarperCollins Publishers Inc: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Soderstrom, S.B.; Weber, K. Organizational structure from interaction: Evidence from corporate sustainability efforts. Adm. Sci. Q. 2020, 65, 226–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, A.; Clarke, A.; Huang, L. Multi-stakeholder partnerships for sustainability: Designing decision making processes for partnership capacity. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 160, 409–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hengst, I.A.; Jarzabkowski, P.; Hoegl, M.; Muethel, M. Toword a process theory of making sustainability strategies legitimate in action. Acad. Manag. J. 2020, 63, 246–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Hart, S. The fortune at the bottom of the pyramid. Strategy Bus. 2002, 26, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnani, A. Fortune at the bottom of the pyramid: A mirage. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2007, 49, 90–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugmann, J.; Prahalad, C.K. Cocreating business’s new social compact. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2007, 85, 80–90. [Google Scholar]

- Chesborough, H.; Ahern, S.; Finn, M.; Guarrez, S. Business models for technology in the developing world: The role of non-governmental organizations. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2006, 48, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zott, C.; Amit, R. Business model design: An activity system perspective. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seelos, C.; Mair, J. Profitable business models and market creation in the context of deep poverty: A strategic view. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2007, 21, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- London, T.; Hart, S.L. Reinventing strategies for emerging markets: Beyond the transnational model. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2004, 35, 350–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raynor, J.; Cardona, C.; Knowlton, T.; Mittenthal, R.; Simpson, J. Capacity Building 3.0: How to Strengthen the Social Ecosystem. 2014. Available online: https://www.issuelab.org/resource/capacity-building-3-0-how-to-strengthen-the-social-ecosystem.html (accessed on 20 December 2019).

- Reed, A.M.; Reed, D. Partnerships for development: Four models of business involvement. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 90, 3–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algoso, D. Feeling Frustrated by Your Job in Development? Become an Extrapreneur. The Guardian. 1 September 2015. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development-professionals-network/2015/sep/01/extraprenuer-frustrated-working-in-development-build-your-own-team-of-people (accessed on 5 June 2019).

- Battilana, J.; Dorado, S. Building sustainable hybrid organizations: The case of commercial microfinance organizations. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 1419–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autio, E.; Thomas, L. Innovation ecosystems: Implications for innovation management. In The Oxford Handbook of Innovation Management; Dodgson, M., Gann, D.M., Phillips, N., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mair, J.; Marti, I.; Ventresca, M.J. Building inclusive markets in rural Bangladesh: How intermediaries work institutional voids. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 819–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohanyan, A. NGOs, IGOs, and the Network Mechanisms of Post-Conflict Global Governance in Microfinance; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, A.; MacDonald, A. Ourcomes to partners in multi-stakeholder cross-sector partnerships: A resource-based view. Bus. Soc. 2019, 58, 298–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, D.A.; Williams, T.A.; Zhao, E.Y. A framework for exploring the degree of hybridity in entrepreneurship. Acad. Manag. Percpect. 2019, 33, 491–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, J.E.; Seitanidi, M.M. Collaborative value creation: A review of partnering between nonprofits and businesses. Part 2: Partnership processes and outcomes. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2012, 41, 929–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitanidi, M.M.; Koufopoulos, D.N.; Palmer, P. Partnership formation for change: Indicators for transformative potential in cross sector social partnerships. J. Bus. Ethic 2010, 94, 139–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracey, P.; Stott, N. Social innovation: A window on alternative ways of organizing and innovating. Innovation 2017, 19, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, D.; Maxfield, R. Foresight, complexity, and strategy. In The Economy as an Evolving Complex System II; Arthur, W.B., Durlauf, S.N., Lane, D., Eds.; Westview Press: Bouler, CO, USA, 1997; pp. 169–198. [Google Scholar]

- Russo, M.; Hughes, T.P. Complementary innovations and generative relationships: An ethnographic study. Econ. Innov. New Technol. 2000, 9, 517–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.; Kramer, M. Creating shared value. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 1/2, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y. Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- George, G.; Bock, A.J. The business model in practice and its implications for entrepreneurship research. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 83–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L. Capitalism at the Crossroads: Next Generation Business Strategies for a Post-Crisis World, 3rd ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Adner, R.; Kapoor, R. Value creation in innovation ecosystems: How the structure of technological interdependence affects firm performance in new technology generations. Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 31, 306–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumate, M.; Hsieh, Y.P.; Oconnor, A. A nonprofit perspestive on business-nonprofit partnerships: Extending the symbiotic sustainability model. Bus. Soc. 2018, 57, 1337–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dattée, B.; Alexy, O.; Autio, E. Maneuvering in poor visibility: How firms play the ecosystem game when uncertainty is high. Acad. Manag. J. 2018, 61, 466–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.L.; Chen, V.Z.; Sunny, S.A.; Chen, J. Venture capital as an ecosystem engineer for regional innovation co-evolution in an emerging market. Int. Bus. Rev. 2019, 28, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adner, R. Match your innovation strategy to your innovation ecosystem. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 98–107. [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor, R.; Lee, J.M. Coordinating and competing in ecosystems: How organizational forms shape new technology investments. Strateg. Manag. J. 2013, 34, 274–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobides, M.G.; Tae, C.J. Kingpins, Bottlenecks, and Value Dynamics Along a Sector. Organ. Sci. 2015, 26, 889–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azoulay, P.; Repenning, N.P.; Zuckerman, E.W. Nasty, Brutish, and Short: Embeddedness Failure in the Pharmaceutical Industry. Adm. Sci. Q. 2010, 55, 472–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repenning, N.P.; Sterman, J.D. Capability traps and self-confirming attribution errors in the dynamics of process improvement. Adm. Sci. Q. 2002, 47, 265–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagani, M. Digital business strategy and value creation: Framing the dynamic cycle of control points. MIS Q. 2013, 37, 617–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccagnoli, M.; Forman, C.; Huang, P.; Wu, D.J. Cocreation of value in a platform ecosystem: The case of enterprise software. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 263–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelman, D.C.; Singer, M. Competing on customer journey. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2015, 93, 88–100. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, P.J.; De Meyer, A.D. Ecosystem Advantage: How to successfully harness the power of partners. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2012, 55, 24–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidsson, P. Entrepreneurial opportunities and the entrepreneurship nexus: A re-conceptualization. J. Bus. Ventur. 2015, 30, 674–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidsson, P.; Recker, J.; Briel, F.V. External enablement of new venture creation: A framework. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2018. Available online: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/119185/ (accessed on 5 January 2020). [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building theories from case study research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research, 4th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Welch, C.; Piekkari, R.; Plakoyiannaki, E.; Paavilainen-Mäntymäki, E. Theorising from case studies: Towards a pluralist future for international business research. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2011, 42, 740–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, A.L.; Bennett, A. Case Studies and Theory Development in the Social Sciences; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Aldine Transaction: Chicago, IL, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Gioia, D.A.; Corley, K.G.; Hamilton, A.L. Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology. Organ. Res. Methods 2013, 16, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ricciardi, F.; Zardini, A.; Rossignoli, C. Organisational dynamism and adaptivebusiness model innovation: The triple paradox configuration. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5487–5493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.; Friesen, P.H. Organizations: A Quantum View; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- North, D.C. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Grief, A. Insitutions and the Path to the Modern Economy: Lessons from Medieval Trade; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, D.; Maxfield, R. Ontological uncertainty and innovation. J. Evol. Econ. 2005, 15, 3–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, D.; Pumain, D.; Leeuw, S.E.V.D.; West, G. (Eds.) Complexity Perspectives on Innovation and Social Change; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. Co-creating unique value with customers. Strategy Leadersh. 2004, 32, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krackhardt, D.; Porter, L.W. The snowball effect: Turnover embedded in communication networks. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brezis, E.; Verdier, T. Political institutions and economic reforms in Central and Eastern Europe: A snowball effect. Econ. Syst. 2003, 27, 289–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swierczek, A. The impact of supply chain integration on the “snowball effect” in the transmission of disruptions: An empirical evaluation of the model. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 157, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foss, N.J.; Saebi, T. Fifteen years of research on business model innovation: How far have we come, and where should we go? J. Manag. 2016, 43, 200–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, C.M.; Ojomo, E.; Dillon, K. Cracking frontier markets. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2019, 1/2, 90–101. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez, S.A.; Barney, J.B. Discovery and creation: Alternative theories of entrepreneurial action. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2007, 1, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, S.A.; Barney, J.B. Entrepreneurial opportunities and poverty alleviation. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2014, 38, 159–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramoglou, S.; Tsang, E.W.K. A realistic perspective of entrepreneurship: Opportunities as propensities. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2016, 41, 410–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; Newey, L.R.; Li, Y. On the frontiers: The implications of social entrepreneurship for international entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2014, 38, 137–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, S.; Dew, N.; Sarasvathy, S.D.; Song, M.; Wiltbank, R. Marketing under uncertainty: The logic of an effectual approach. J. Mark. 2009, 73, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J.; Marti, I. Social entrepreneurship research: A source of explanation prediction, and delight. J. World Bus. 2006, 41, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.L.; Im, J. Cutting microfinance interest rates: An opportunity co-creation perspective. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2015, 39, 101–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, J.; Sun, S.L. Profits and outreach to the poor: The institutional logics of microfinance institutions. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2015, 32, 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobb, J.A.; Wry, T.; Zhao, E.Y. Funding financial inclusion: Institutional logics and the contextual contingency of funding for microfinance organizations. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 2103–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.P.; Spanjol, J.; Sun, S.L. Social innovation in an interconnected world: Introduction to the special issue. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2019, 36, 662–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.L.; Zou, B. Generative capability. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2019, 66, 636–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorberg, W.H.; Bekkers, V.J.J.M.; Tummers, L.G. A systematic review of co-creation and co-production: Embarking on the social innovation journey. Public Manag. Rev. 2015, 17, 1333–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. Co-creation experiences: The next practice in value creation. J. Interact. Mark. 2004, 18, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.L.; Xiao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, X. Building business models through simple rules. Multinatl. Bus. Rev. 2018, 26, 361–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Date | Memorabilia of co-op L (2014–2018) |

| 2014.09 | The first prefecture-level city agricultural product co-branding L was officially launched in China. |

| 2014.10 | The local government specifically held the Ecological Boutique Agricultural Fair in Hangzhou and had a press conference on the co-op L Model and co-branding L. |

| 2015.09 | The first anniversary of the co-branding L was held in Hangzhou. Agricultural brand experts, the head of co-op L, and officials of the local government discussed the future development direction of co-op L. |

| 2016.08 | The first store of co-branding L opened. The store was built by the online shopping platform “Yuemi Mall.” This store was dedicated to promoting the sale of co-op L agricultural products. |

| 2016.10 | Co-op L participated in the Hundred Countries Conference of China’s Agricultural Brand, and made a special forum to analyze the “landing codes” of co-op L. |

| 2016.12 | City L won the “2016 China Top Ten Social Governance Innovations” with co-op L to promote ecological development. By the end of 2016, 230 agricultural firms and farmers wanted to participate in co-branding building, and the products have been sold to more than 20 provinces and cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen, among others. The average premium of agricultural products has reached 33% and the total sales exceeded 2.86 billion U.S. dollars. |

| 2017.09 | The first flagship store of co-branding L was established in Hangzhou. The Ecological Boutique Agricultural Fair of city L was opened at the Hangzhou Peace Exhibition Center. The co-branding L Development Conference and the launching ceremony of a private enterprises’ communicating event were held in City L, Zhejiang Province. |

| 2017.10 | The Zhejiang provincial government upgraded co-branding L to build a domestic leading agricultural co-branding. |

| 2017.12 | The International Certification Alliance Inaugural Meeting was held in city L. Co-op L participated in the European Tasting Presentation in Paris. |

| 2018.01 | Co-op L established new channels for online promotion, using the “WeChat small program” to develop the L marketing small program. This led to exploring the new model of online group marketing under the leadership of Co-branding L. |

| 2018.04 | Super Neighbors was opened as a commodity experience center of L tourism. |

| 2018.06 | By the end of June, there were 733 members of the 1122 cooperation bases. |

| 2018.10 | The IOT control center of L began construction. |

| 2018.11 | The co-branding L promotion conference was held in Changsha International Convention and Exhibition Center. |

| 2018.12 | Products of co-branding L appeared in the Jiaxing Tiantian Agricultural Exhibition. |

| Date | Memorabilia of co-op W (2017–2018) |

| 2017.03 | Longfei Wu was appointed as director of co-op W. |

| 2017.12 | Wuyi Rural E-Commerce Co. Ltd. was established as the subordinate of co-op W. |

| 2018.01 | Co-branding W was launched officially in January 2018, which originated from a tea brand W that had been in operation since 1994. |

| 2018.09 | At the first Chinese Farmers’ Harvest Festival, the Agricultural Products Exhibition center in county W opened and various products of co-branding W were provided to consumers. |

| 2018.10 | The 12th Hot Spring Festival and the 9th International Health Expo in county W had a grand opening. W appeared at the Expo and focused on featured agricultural products from county W. |

| Company file and media report summary | Co-op L | Co-op W | Co-op L | Co-op W |

| Number | Time range (year) | |||

| Search engine | 1 | 1 | 2014–2018 | 2017–2018 |

| Annual report | 4 reports | 1 report | 2014–2018 | 2018 |

| Media coverage | 24 articles | 11 articles | 2014–2018 | 2017–2018 |

| Observation and interview summary | Co-op L | Co-op W | Co-op L | Co-op W |

| Number | Dialogue and Interview time (hours) | |||

| Observation by the two authors | 3 months | 3 months | 16 | 16 |

| Managers of the two co-ops | 1 person | 1 person | 2 | 2 |

| Employees of the two co-ops | 3 persons | 3 persons | 3 | 3 |

| Leaders of agricultural firms cooperating with the two co-ops | 3 persons | 2 persons | 3 | 2 |

| Farmers cooperating with the two co-ops | 2 persons | 5 persons | 2 | 3 |

| Customers of the two co-brandings | 6 persons | 10 persons | 2 | 2.5 |

| Co-op L | Co-op W | |

|---|---|---|

| The first stage: value blueprint | Co-op L establishes rural property rights trading platform to transfer land-use rights. | Co-op W uses the strategy of “one village, one product” to build the co-branding. |

| Co-ops L and W develop local agriculture by co-branding management and green development, which are supported by local government. | ||

| The second stage: pilot demonstration | Co-op L establishes data center to offer service from land to table for firms, farmers, consumers, and governments. | Farmers trust co-op W, while some firms hesitate to trust and participate in co-branding. |

| Co-ops L and W select locally welcomed agricultural products to perform pilot demonstration and monitor co-branding building and product quality. | ||

| The third stage: scaling up | Co-op L establishes quality and safety information management platform to trace products. | The demonstration works and firms learn that there will be win-win cooperation. |

| Co-ops L and W expand their online market, while opening stores in the community. | ||

| The fourth stage: snowball | Co-op L helps farmers and firms to get financial service. | Co-op W attracts more farmers and firms to build co-branding. |

| Co-ops L and W, local governments, and business partners form their respective social ecosystems together. | ||

| Opportunity Discovery for Poverty Alleviation | Opportunity Co-creation in Generative Partnership | |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Possibility of creating new means when competitive imperfections exist in the factor or product markets [75] | Increased opportunity structure implies more space and fewer constraints for the marginal consumer/farmer to exploit and engage in entrepreneurial activities. |

| Elements of opportunity | Self-employment opportunities; Opportunities “exist in pre-existing markets or industries. Clearly definable market gaps. Exist whether an entrepreneur exploits them or not” [76]; There are opportunities “to be actualized into profits through the introduction of novel products or services” [77]. | Fostering socially desirable behaviors; Cultivating social capital; Promoting community development; Co-creating values of mutual benefits rather than self-interest [78]; Triggering and shaping “outcomes of a variety of new venture creation attempts across a range of actors” [52] (p. 676). |

| Theoretical foundations | Uncertainty and institutions of human capital, property rights, and financial capital for wealth creation and poverty alleviation [76]. | Effectuation theory [79], social entrepreneurship [80], and actor-external enabler nexus on opportunity [52]. |

| Theoretical focus | Focus on the entrepreneurial process and value creation at the individual or organizational levels [75]. | Accumulation of multiple stakeholders, entrepreneurs, and their interaction and experiential learning to build social value propositions. |

| Level of analysis | Individual level | Multiple levels: ecosystem (macro); multiple stakeholder, entrepreneur, and marginal poor/consumers (micro). |

| Means of making opportunity | Discover/identify opportunity | Enable/facilitate the actors (NGOs and the poor) to exploit opportunities. |

| Purpose of opportunity | Exploiting the competitive imperfections to pursue economic profits. | Expanding opportunities for the poor (outreach); Increasing social welfare for inclusive growth. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhu, R.; Sun, S.L. Fostering Generative Partnerships in an Inclusive Business Model. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3230. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083230

Zhu R, Sun SL. Fostering Generative Partnerships in an Inclusive Business Model. Sustainability. 2020; 12(8):3230. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083230

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Rong, and Sunny Li Sun. 2020. "Fostering Generative Partnerships in an Inclusive Business Model" Sustainability 12, no. 8: 3230. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083230

APA StyleZhu, R., & Sun, S. L. (2020). Fostering Generative Partnerships in an Inclusive Business Model. Sustainability, 12(8), 3230. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083230