1. Introduction

The accelerating climate crisis and tipping points in critical planetary boundaries [

1,

2] are pushing forward transformation processes toward global sustainability. Education plays a pivotal role in these transformation processes as it fosters the capacity to contribute to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals in the cognitive, socio-emotional, and behavioral domains [

3]. While the UN Decade and the UNESCO Global Action Programme (GAP) on Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) supported the scaling of ESD [

4] in multi-faceted ways, ESD is still not implemented comprehensively in all educational areas. The scaling of ESD is realized by multi-stakeholder governance networks in polycentric systems with many centers of influence [

5]. That is why questions of governance become apparent, and research studies on governance promise to deliver valuable insights on the future scaling of ESD.

This article aims to reveal the governance in the sense of the coordination of action among different actors and their positioning toward structures while realizing the GAP in Germany as a multi-level educational system. The historical background of ESD in Germany is influenced by a strong community of self-organized networks of non-state actors from civil society, educational practice, and academia who built up bottom-up structures during the implementation of the UN Decade of ESD [

6]. At the end of the UN Decade, when nearly 2000 projects and organizations were awarded for their excellent ESD practices, the fundamental goal was to bring ESD from the level of projects to the level of educational structures—the slogan for this strategy in Germany was “From Project to Structure” [

7]. Therefore, the implementation of the GAP was formally led by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (which will also coordinate the follow-up program ESD for 2030). However, due to the federal system prevailing in Germany, the individual federal states are mainly responsible for implementation. Additionally, municipalities play an important role for ESD as many decisions are made on the local and regional level, have a local impact and, most important, ESD is realized locally [

8]. Yet, for local authorities ESD is no mandatory topic but depends on decision makers’ own choices. Therefore, the situation varies a lot from city to city and region to region.

Nevertheless, the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research has designed a comprehensive and participatory multi-stakeholder process with more than 600 persons involved. It includes different bodies—a National Platform, six Expert Forums (and an additional Youth Forum), and ten Partner Networks. In all of these committees, actors from different sectors are represented (ministry officials at the national and federal state level, policymakers, academia, civil-society organizations, educational practitioners, etc.). Especially the Expert Forums were responsible for formulating a National Action Plan (NAP) that was adopted in June 2017 by the National Platform [

9]. It includes a total of 130 objectives and 349 measures for scaling ESD in the different educational areas consisting of early childhood education, school education, vocational education and training, higher education, organizations of non-formal learning, and local authorities. Regarding the end of the GAP and the start of the new program of ESD for 2030, their task is to further develop and realize the NAP.

The overall research perspective of educational governance, used within this article, aims at understanding the coordination of action [

10] among the different actors that are involved in this policy process of Germany’s multi-level educational system [

11,

12]. Such coordination implies a mutual adjustment of actions and the management of interdependencies among the various actors involved in regulating collective issues [

13]. The governance perspective generally expands older conceptions that divide the subject matter into a hierarchical juxtaposition of “steering subjects” and “steered objects” [

14] because there is a “profound skepticism about the possibilities of hierarchical control of complex social systems” [

15]. Research on the implementation of state-led innovations shows that the target groups of these state-regulated reforms can resist, evade, or change the policy innovation. Instead, the governance perspective used here takes into account the multi-faceted interdependencies, communicative processes, and boundary work among state and non-state actors that take part in the realization of policies [

16]. The concept of “boundary work” goes back to science and technology studies and initially focused on how scientists socially construe, maintain, or advocate for demarcations between specific fields of knowledge (i.e., disciplines, scientific knowledge, and non-scientific knowledge) [

17] (p. 64, based on [

18]). From the governance perspective, boundary work is used as a concept to better understand how different actors perform the “ability not only to produce knowledge but also new social orders” [

19] (p. 278). It includes the systematic bridging of boundaries among different actors involved in policy processes [

20] (p. 68) and, thereby, is used to understand how different actors constitute and cross the boundaries between them [

10]. The educational governance perspective applied in this study does not aim at defining normative concepts of good or bad governance in the sense of state-centered political leadership [

21] (p. 26). Rather, it gives an analytic perspective to better understand the interdependent modalities of coordinating actions among various actors.

Although governance processes are well researched in the field of education and sustainability policies, as yet little is known about the governance of ESD or related educational concepts like Climate Change Education (CCE) [

8] (p. 4). International organizations such as UNESCO have influenced the relevance given to ESD and CCE on the level of the nation-states, and “their bureaucracies are significantly involved in the processes of goal formulation and agenda setting” (ibid. p. 12). Particularly UNESCO has encouraged national governments to develop strategies and action plans to implement ESD in all educational areas as well as promoting public awareness and broader participation through cooperation with relevant stakeholders [

22]. UNESCO is thereby following a particular logic of ESD implementation: to achieve participation organized by the nation-state that leads to collective ownership by the different ESD actors involved [

23]. This strategy fits well with overall insights about successful educational innovations that enhance reform ownership [

24]. While the process of transferring the social innovation of ESD usually takes place differently not only in each country or region but also within different educational areas [

25], setting up appropriate strategies is a complex task in general. National governments tend to choose so-called “soft” instruments, such as consultations, networking structures, and guidelines, and even “take the role as mediators or coordinators of an ongoing dialogue and cooperation on promotion of ESD” [

26] (p. 36) to reach collective ownership.

Nevertheless, the national support of collective leadership seems to be partly a paradoxical task for governments, as ESD is mainly realized in local networks of practitioners, regional, or even federal ministry officials, where the actors tend to voluntarily commit their energy and resources to the idealistic goal of strengthening ESD [

27]. Recent studies about the governance of ESD in Germany concluded that during the UN Decade, a dynamic of structures among various actors evolved, “in which hybrid constellations and processes emerge[d]” [

28]. Here the different coordination mechanisms among state and non-state actors become especially apparent when developing ESD policies and putting them into practice. Although the cooperation among different sectors does not seem to be the dominant mode of cooperation [

29] (p. 15), studies about the changing relationships between state actors and civil-society actors in the implementation of the UN Decade of ESD in six federal states in Germany [

23,

30] showed that the state actors (ministry officials) and representatives from civil-society organizations have built “intermediary spaces of negotiation” [

30] between the different sectors. These intermediary spaces of negotiation were manifested in new structures, committees, or political bodies that were responsible for coordinating the activities during the UN Decade. The respective functions, responsibilities, and roles of the different actors within these processes became blurred. After a phase of intense negotiations among state and non-state actors, when more network-oriented and equal cooperation with joint decision-making among the actors occurred, the state actors gained more influence and a leading role at the end of the UN Decade [

23] p. 221).

Additionally, previous research has revealed some insights about the effects of such intermediary spaces of negotiation on the actors involved. For instance, several studies found that policymakers [

26] (p. 39) or civil-society actors [

31] (p. 422) became confused about their roles when working together for scaling ESD. Another study focused on the importance of trust, commitment, framing, and—most crucially—reflexivity when actors from different sectors are working together in multi-stakeholder governance networks and solving wicked sustainability problems [

32]. Still, more knowledge is needed on how different actors work together in multi-stakeholder governance networks for ESD and particularly on how they construe, maintain, or even bridge sectoral boundaries during this process. In addition, it is as yet unclear how they refer to their own and other organizations and structures when working within or across these boundaries. Structures within this article refer to formal, established political and organizational rules, norms, bodies, documents, resources, and standards shaping the individual sectors. In accordance with Giddens’s theory of structuration, which is even applied in educational governance [

33] (p. 352), we understand “structure” as interdependent and reciprocal with the actions of actors. Structures have an enabling and limiting character, in which actions are made possible and legitimized, but at the same time limited and regulated [

34] (p. 174). Actors are always embedded in structures, but do not necessarily have to adhere to them directly. Through their actions, they reproduce or change structures [

34] (p. 175). Giddens sees an inherent power in the actions of actors as they can reflect on their own knowledge-based actions within structures.

The knowledge-based coordination of action between different actors sometimes also includes implicit forms, such as using implicit knowledge, which is the basis of everyday communication but is usually not made explicit. Following Bourdieu, implicit knowledge can be understood as rooted in his concept of habitus [

35]: social and cultural backgrounds inscribed in individuals that build up implicit knowledge affect how they perform social and interactive actions or practices. However, because their implicit knowledge is based on experiences, it is more difficult to capture than theoretical knowledge. In contrast to theoretical knowledge, implicit knowledge is explored through the way something is done, rather than through utterance itself [

36]. Implicit knowledge can be understood as the “modus operandi of the production of social practice” [

36] (p. 187). Although there is little theoretical discussion of the significance of social practices in governance research, we believe it is inherent in the study of the coordination of action in educational governance processes. Social practice is what evolves within the introduced multi-actors networks that our study analyzes. As governance research aims at investigating such interactive actions, it is important not to neglect the existence of implicit knowledge within the coordination of action and at least to think along with it, as it is fundamental to be understood as guiding action [

37]. One approach to pursue this aspect is presented in our study, where we tried to reconstruct a more explicit knowledge-based understanding of scaling ESD as well as more implicit forms of patterns of argumentation.

Given that the stakeholder process in Germany aims at institutionalizing and, thereby, scaling ESD from the level of projects to the level of structures, it is pivotal to understand the dynamics among the actors involved when coordinating actions. Therefore, this governance study examines their interdependencies, their boundary work, and the informal discursive spaces for action. Against this background, mechanisms of actor coordination among the different state actors (policymakers and administrative actors) and non-state actors (researchers, civil-society actors, and educational practitioners) in the bodies of the GAP were analyzed. The main research questions were: How do the actors in the GAP bodies coordinate their actions when realizing the National Action Plan? How do they construe, maintain, or even bridge boundaries when coordinating actions? And which sector-specific characteristics can be revealed in their active engagement with boundaries?

To answer these questions, we organized and analyzed six focus group discussions with actors from different sectors for each educational area. The methodical approach will be outlined in

Section 2. The results, presented in

Section 3, reveal that every sector showed different patterns in regard to the respective boundary work that ranged from a more intra-sectoral demarcation approach to a more inter-sectoral networking approach. The discussion in

Section 4 will show that this variation can be explained by different theoretical and empirical insights for the respective actors. Besides this, both of these perspectives are highly valuable for scaling ESD from the level of projects to the level of structures. It is, however, crucial for ESD actors working in multi-actor governance networks to reflect on their preferred position and to become aware of appropriate positionings for specific tasks.

2. Materials and Methods

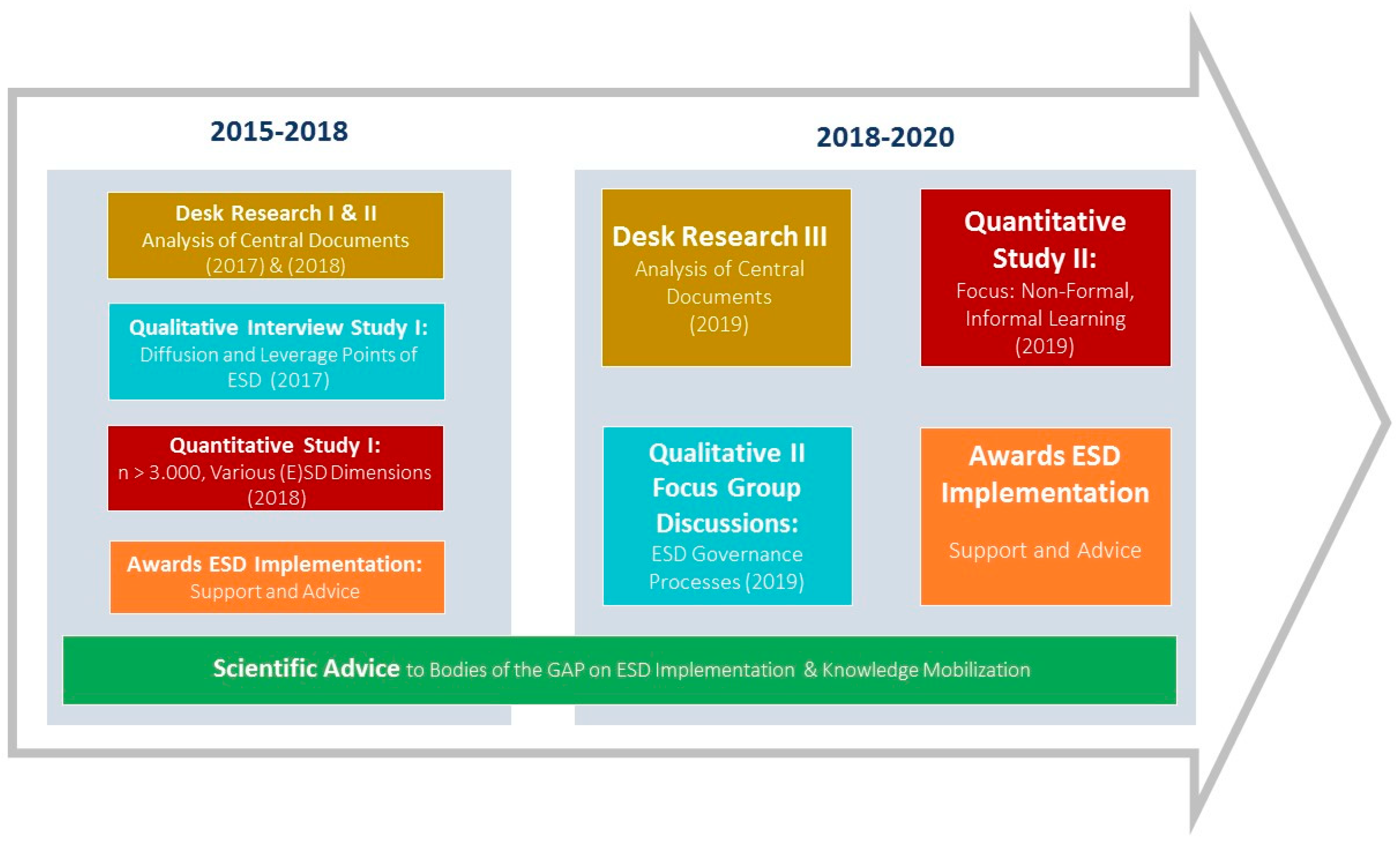

The research presented in this article is part of the Germany-wide monitoring on ESD (see

Figure 1), which is funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research and carries out extensive accompanying research on the implementation of the GAP for ESD. It is located at the department of the scientific advisor for the National Platform on ESD. As ESD-monitoring approaches benefit from mixed-method design [

38], it applies a set of differing approaches.

This article refers to the Qualitative Study 2 focus group discussions (see

Figure 1) and presents and discusses the first partial results. A qualitative research approach was chosen to gain a deeper understanding of the coordination of actions and to reveal its embedding within framing social systems and realities [

39,

40].

Focus group discussions [

41] were used for data collection. Based on a

sampling strategy, which covered all relevant sectors in the different educational areas, four to seven representatives from different sectors (policy, administration, academia, civil society, and educational practice) working in the same educational area were invited for a total of six discussions (one for each educational area, in sum 33 participants). The participants were mainly active members in the different bodies of the GAP in Germany. All of them had a high degree of expertise in the respective educational field and related educational organizations.

The method of focus group discussions for

data collection was based on the assumption that attitudes and opinions in daily lives do not exist in isolation for individual persons but emerge through social exchange with others and, therefore, can be better captured within group interactions. The potential of the method was particularly evident in the fact that in the discussions, the general negotiation processes were reconstructed in situ. For this reason, the data collection also covered implicit knowledge as the basis for a certain way of coordinating actions [

42]. As implicit knowledge is not theoretical knowledge, it can only be captured by reconstructing cooperation, not by explicit explanation alone. In the focus group discussions, the actors not only talked with each other about their cooperation but actually worked with each other toward a knowledge-based and common understanding of how to scale ESD in the respective area. This means that they actively construed, maintained, or bridged their boundaries toward each other. Although the groups were compounded artificially by the researchers, there was a considerable similarity to the “natural” constellations in the GAP committees. For this reason, we were able to reconstruct the communicational actions and interactions and relate these to the actors’ coordination of actions in the broader community. The focus group discussion started with a provocative discussion stimulus (find questionnaire in

Appendix A). After an initial discussion among the participants about this opening, further questions were raised about the scope of their own actions or recommendations for a future program. Furthermore, the particularities of the different educational areas were captured using a few questions.

For the

analysis of the data the transcripts of the six focus group discussions were analyzed with a thematic qualitative text analysis [

43,

44] as one type of qualitative text analysis using a theory-led system of categories [

45] (p. 4). Kuckartz refers to a multi-stage process of categorizing including inductive and deductive procedures within the analysis, whereby he emphasizes the importance of inductive categories, especially for explorative research, through its principle of openness of results [

43]. He suggests a seven-step procedure: the first step contains the initial text work, where the transcripts are read and important passages are highlighted and commented on. During this process —as well as during all the following steps of the analysis—the individual researchers kept a research journal on distinct features and interpretation ideas. Additionally, every focus group discussion was summarized. The second step included establishing and applying core categories that were developed on the basis of key publications in the field of educational governance [

43,

46]. The core categories of the deductive category building—Kuckartz refers to the more fitting definition of a priori categories—included actors and constellations of actors, rights of disposal, regulatory and service structures, multi-level systems, understanding of ESD, reflexivity, and agency. In the third, fourth, fifth, and sixth steps, the coding process was realized as the researchers coded the text of the transcripts line by line. To ensure the quality of the coding process, at least two researchers analyzed parts of the transcripts. If the coding differed, it was discussed within the researcher team until a consensus was reached [

43]. As part of the coding procedures, the core categories were differentiated into sub-categories, and the data were coded again against the reviewed system of categories.

After finalizing the coding procedure and with the aim of preparing a case comparison, summaries of each person’s argumentation were compiled within each of the focus group discussions (seventh step). For the following process of systematic in-depth comparison, the representatives of the single sectors in each educational area were treated as single cases. For example, all text passages of the person who represented the ministries of the federal states in Germany in early childhood education (one case) were summarized. These case-based summaries were included in a context matrix for each educational area. To grasp the dynamics of interaction among the actors within the focus groups, we analyzed how the persons who represented one specific case coordinated their actions in contrast to the specific content of what they were saying. The question of how actors do something—and not merely what they are saying—aims at understanding the deeper-lying patterns of implicit knowledge that are embedded within the habitus and background of the individual actor. We tried to capture this implicit knowledge expressed in their social practices by looking for the ways in which the actors confirmed or challenged each other’s positions (even non-verbally through ‘mmhh’) or analyzing the proportion of speeches. This clearly showed that implicit knowledge influenced the implicit way in which the actors dealt with their boundary work. By analyzing how every single actor coordinated their individual actions within the data processed, patterns in each actor’s positioning opened up. To further compare these individual positions, we not only contextualized them within the specific educational area (focus group) but also between their sectoral affiliations. Subsequently, the positions of all actors were traced through the comparison of the various actors in one sector. To give an example of how this was methodologically set up—all representatives from the ministries (of the federal state level, the national level, and even the local authority level) were compared. Within this procedure, the reference to existing and required structures stood out in all cases as a distinguishing feature. During the constant comparison of the single cases, it emerged that the individual actors, regardless of their sectoral or educational affiliation, referred to how they interact with given or new structures in order to implement ESD and, thereby, differed in their patterns of argumentation.

The article focusses on the patterns of argumentation with regard to the different sectors to point out the typical mechanisms in ESD actors’ coordination of actions in Germany. Additional literature was used to support and validate possible characteristics within each sector. These characteristics of the actors’ positions in the respective sectoral cases were further elaborated through an interactive interplay of empirical basis and theoretical integration. For example, we were able to identify inductive patterns of the coordination of action per sector, but with the help of sector-specific literature, we were able to sharpen them and compare them as opposite positions. The whole process was realized in weekly interpretation sessions that were organized for nearly one year of research. Using inductive loops within deductive research was particularly fruitful, as it opened up new paths of interpretation, and revealed overarching but also sector-specific factors on boundary work for scaling ESD.

3. Results

We revealed different sectoral positionings, which were highly interlinked with explicitly expressed and implicitly reconstructed patterns consisting of different understandings of professionalism, rationalities, and practices. These positionings represented ideal-typical patterns which emerged from the continual comparison of the single sector-specific cases among the focus group discussions. This does not mean that specific actors represented or reproduced the pattern personally. Rather, it shows heuristic juxtapositions that symbolize the ideal-typical patterns: On the one hand, patterns were found in which actors strongly identified themselves with their organization and their sectoral principles. These patterns could be described as highly functional for their respective organization and the actors were firmly positioned within the sector and explicitly referred to their own routines. On the other hand, we found patterns in which actors went beyond their respective sectoral logic and intensively referred to other organizations, sectors, and network structures beyond their own sector. Here the anticipated perspectives of other sectors were integrated into the actors’ reasoning. In the following sections, we present these positionings for each sector separately.

3.1. Administration

The patterns found within the positionings of ministry officials in the federal, state, and local government ranged between functional administrative on the one hand and creative administrative on the other. The functional administrative pattern was characterized by putting the characteristics and responsibility of the person’s own role in a highly specialized administrative apparatus at the center. The reasoning within this pattern was symbolized by the fact that actors objectified their person concerning their own function (serving the state) for the realization and controlling of administrative regulations. Following this pattern, individual persons could not achieve anything on their own but must instead rely on given structures: “The level of single persons is not sufficient” (Administration 4: 605). The actors showed a high level of expertise regarding the administrative tasks entrusted to them. In the implementation of ESD, functional administrative patterns focused above all on the limitations for actions of their specific unit in the multi-level system of the German education system. This applied to the different administrative levels (nation, regional, and local). Cooperation with other actors during the discussion was characterized by the constitution of boundaries between administrative organizations and other sectors that were thus considered inherent in the structure. In this pattern, the focus was, therefore, mainly on limitations of the scope of the person’s or institution’s own actions: “It is even more difficult at the national level because we cannot govern directly. The decisions are made elsewhere. (…) [W]e do not have any kind of [influence]—at any level. Also not financially” (Administration 1: 765–772).

The creative administrative pattern was characterized by arguments based on a designing and, in some cases, also steering claim, which is at the same time inherent in a potential authority of interpretation and attempts to reframe the opinions of other actors. Actors who followed this pattern actively sought ways to exploit or even expand their own options for action, either concerning their own organization or in relation to inter-sectoral cooperation. They positioned themselves as creative subjects who transcend the purely functional fulfillment of bureaucracy in favor of more proactive actions. “The fascinating thing with ESD is its relation to the SDGs (Sustainable Development Goals). It plays out on completely different levels. We have a commitment of the world society—in quotation marks. We have actors who work in their basic institutions. And I believe that when it comes to the question of who participates and who decides, it is a very complex task to mediate between these levels. I think that is the key point. And [...] we are all working on it, but it is extremely important to always connect these levels with each other” (Administration 5: 443–449). Within this quote, the precise self-given task for mediation, moderation, and connecting stakeholders becomes clear. This pattern of transcending the pure fulfillment of bureaucracy was particularly significant for actors with a civil-society ESD background. In the focus group discussions, the actors who represented this pattern sometimes took on multiple perspectives from other sectors represented in the discussion or in the field. They tended to show a greater degree of reflexivity about their own organizational routines and practices. “I have achieved a resolution for the National Action Plan within the [political committee]. But this is not of interest for educators in the kindergartens, if we have met together within [this committee] and adopted a resolution. (…) I am involved in the kindergartens and the ministry at the same time and for this reason, I can say: these are two worlds in which we are working” [Administration 1: 141–146]. The actors who characterized this pattern also acted as moderators of the entire group discussions and, thereby, fulfilled their role of moderating and mediating different perspectives in situ.

3.2. Politics

There were no political decision makers within the focus group discussions, but there were actors connected to politics, such as former politicians or delegates of associations such as self-organized local-authority associations, who gave insights into the rationalities of this sector. Their references to structures differed regarding their understanding of advocacy within the relation between ESD and political actors’ interests. It led to opposing positions depending on whether or not there is an understanding of ESD as a valuable contribution to political interests.

On the one hand, there was a defensive position, defending political representatives from non-engagement in ESD with reference to the interests of political actors. This position stressed that regarding the multitude of issues politics has to deal with under limited time and financial resources, ESD can not necessarily be a priority. It went along with an understanding of ESD as individual ambition, as education is not a mandatory issue on every level but depends on politicians’ own choices (see above). Further, according to this position, ESD was considered to be complicated and, therefore, needed to be broken down in order to not overwhelm political actors. ESD was mainly appreciated when it could be used to convey other policies. Against this backdrop, this perspective aimed at protecting from the additional tasks included in scaling ESD and promoting understanding for those who showed a lack of commitment to ESD. Similarly, structures were adduced as reasons for a lack of commitment. When it came to the acquisition of funding for projects like ESD, for example, one political actor demanded support structures as a prerequisite for activities that otherwise could not be expected: “There should be some kind of support to help municipalities in the first place to find out where there are funds for what. Smaller municipalities, in particular, cannot do this because we now have such a large number of funding opportunities that require an unbelievable amount of administrative work” (Political Actor 6: 368–370).

On the other hand, advocacy was based on an understanding of representing ESD interests in the political framework. This position can be described as proactive. It showed strong ambitions to foster the concept through various strategies. Next to interconnecting ESD with other issues or cost-neutral implementation, those who held this position worked toward proactively creating structures for ESD in practice. This required an examination of the existing structures and the development of strategies for dealing with them (such as cost-neutral actions or new forms of cooperation with other actors, such as networks and projects). One political actor exemplified how cooperation among municipalities worked out how to cope with the structures that impede the realization of a sustainability report: "If I had said: ’I want to make a sustainability report for 4000 euros.’ I would not have gotten approval for it. So, (…) the question is how you can move forward in the matter. We worked on inter-municipal cooperation with City X and Y. (…) It works” (Political Actor 6: 953–960). Later, the person elaborated on the implications in practice: “For its realization, I need support from administration and maybe an engineering office. But if you have such a structure, it gets much easier to realize further ESD activities. They are installed then. That’s positive” (Political Actor 6: 965–968).

3.3. Academia

The cases of the focus group participants from academia went along with the researchers’ self-understanding as merely descriptive on the one hand and transformative on the other. All researchers shared a more critical-questioning pattern of argumentation—they generally tended to take the position of questioning or refuting other participants’ arguments. Within their reasoning, the descriptive researchers acted in a strongly analytical and explanatory manner for the other actors concerning the functional logic of the respective educational areas. “Higher education at the moment is essentially cognitive knowledge transfer. It therefore has nothing to do with people and behavior” (Scientist 4: 838–839). They referred to empirical knowledge, theories, and “a truth” and, thus, based their argumentation strongly on their high level of scientific expertise and belief in their ability to explain “the truth” for others. "[T]he SDGs are just another way of boxing the big issue so we can understand it. That is essentially done through a political logic, and at least it has become a package of goals. […] I would not question them [the SDGs] at all. Why would I?” (Scientist 4: 219–227). This expression of expertise sometimes tended to demarcate from the position that research and teaching can influence the world outside academia and went hand in hand with a low focus on one’s own and others’ rights of disposal. “I am always just one person in the system. I am always a function. And I am addressed as a university teacher in my function” (Scientist 4: 606–609).

The transformative researchers, on the other hand, showed a stronger connection to joint action together with non-scientific actors and advocated creative actions, networking, and the common pursuit of interests in terms of scaling ESD. In their arguments, they made more political demands, suggested specific political activities and structures, and assessed political processes much more strongly using specifically normative positions: “We need more political will. And we need resources to move things forward faster than they are moving now” (Scientist 2: 392–394). Some of them almost took an activist approach for their own and/or a common-good-oriented interest and evinced a proactive search for bridging the gap between academia and practice: “You have to [...] unite, coordinate. And then march over there and say, here, we want this” (Scientist 2: 448–449). When asked about their own scope for action to strengthen ESD, one researcher said: “I would continue to do design-oriented research together with the local players. (...) Finding ways to simply advance (...) ESD” (Scientist 3: 853–860). This pattern of argumentation shows the will to engage civil society in science, transcending boundaries and existing structures of inclusion and exclusion within scientific processes.

3.4. Civil Society

In the civil-society sector, actors’ positions can be divided between the pole of demarcating stances and actions from those of the state actors and the pole of cooperative and supportive civil society with regard to their relation to structure. The demarcating pattern of civil-society actors emphasized their strong independence from the state, insisted on an ambitious implementation process of the GAP on ESD, advocated for an evaluation of the implementation status of the NAP, and criticized a lack of funding. Furthermore, within this pattern some of the previous actions of state actors in the implementation of ESD were disapproved, the actors pushed for transparency, and increased opportunities for civil-society participation—in ESD and beyond. Nevertheless, these positions of civil-society actors were more ambivalent, and within their reasoning, they were jumping back and forth along the spectrum of the demarcating and cooperative pole. Typically, they appreciated the state activities for scaling ESD but demanded more efforts: “The perception and public relations [of ESD] have been unbelievably pushed [...]. But especially at the national level, the involvement of the players, including us, did not take place in an as participatory manner as we would have liked it to be. I am often disappointed that we (…) were not heard and that our ideas were not passed on directly in the form in which they were intended” (Civil-Society Actor 5: 28–40). This pattern of argumentation strongly referred to existing structural limitations.

The cooperative pattern, on the other hand, was expressed by appreciating state actions, defending some state strategies for scaling ESD in the way of “From Projects to Structure” in a partly accommodating manner, and actively exploring the future inter-sectoral potential for actions together with state actors: “Maybe it is too early to assess this [the realization of the GAP in Germany] critically, because all these first impulses to take it up from the bottom and to conduct it on the top, have only been started” (Civil-Society Actor 1: 100–103). When criticizing state actors, the cases who showed this pattern still sought possible points of reference and cooperation. "I do believe that the NAP helps a lot. I can only judge that for the state [XY]. […] It is quite good. (…) But what I believe is that over all the subject makes you feel like a well-fed beggar. Where it is just now becoming interesting for the young people at schools to question themselves critically and to put sustainable education into practice, I totally lack the support” (Civil Society 2: 98–110). Even within this quote, the high degree of ambivalence of the actors’ positioning becomes apparent. Compared with the other discussion participants, the patterns within the representatives of civil-society organizations altogether were more difficult to assign to one side or the other. They frequently varied between the two opposing patterns of demarcating and cooperation and often argued ambivalently between these poles.

3.5. Educational Practice

The educational practitioners’ scope of action was linked inextricably to the organizations and structures of their respective educational areas. Accordingly, the logic specific to the educational area was most strongly reflected in the sector of educational practitioners. The two poles referred to their relation to organizational requirements. The argumentative patterns oriented toward official frameworks were closely connected with the official tasks of the educational practitioners’ function. The argumentation was based on implementing good practice in the context of their daily work that was grounded on educational policy guidelines. The pattern showed a strong identification with formal circumstances and emphasized limited options for action, such as a lack of funding or an insufficient curricular anchoring of ESD: "We just need help sometimes. […] Sometimes it is the case that you do a lot with the children. And they participate and have a lot of ideas. And then it fails a bit because of the implementation. (…) It would be nice if it was also recognized by the political [actors]—If it was recognized and you get support” (Educational practitioner 2: 246–259). The logic of this argumentative pattern especially reaches out for political recognition and support to ease the work. “ESD is a generalist approach, an interdisciplinary approach. It only has a chance if it is implemented in the curricula—no matter of which educational institution. And this is especially true for vocational education and training where it should be integrated in the training curricula” (Educational practitioner 3: 65–69).

On the other hand, the creative pattern beyond official requirements and routines looked for additional options. Actors who followed this pattern were able to shape their own initiatives and tried to find room for maneuver beyond the search for financial resources. They could gather further, new, and relevant information and could question the given implementation structures. Thus, the active search for windows of opportunity crystallized in the empirical results of the focus group discussions as the clearest characteristic of the creative pattern. “In the past, we asked the municipal institution for money for projects, and this didn’t work. Then we started actually realizing projects. And it had a very nice effect on the municipality because the municipality then said: ’We want to participate. We want to support that.’ And that’s how we reach them” (Educational Practitioner 1: 297–314).

3.6. Summary

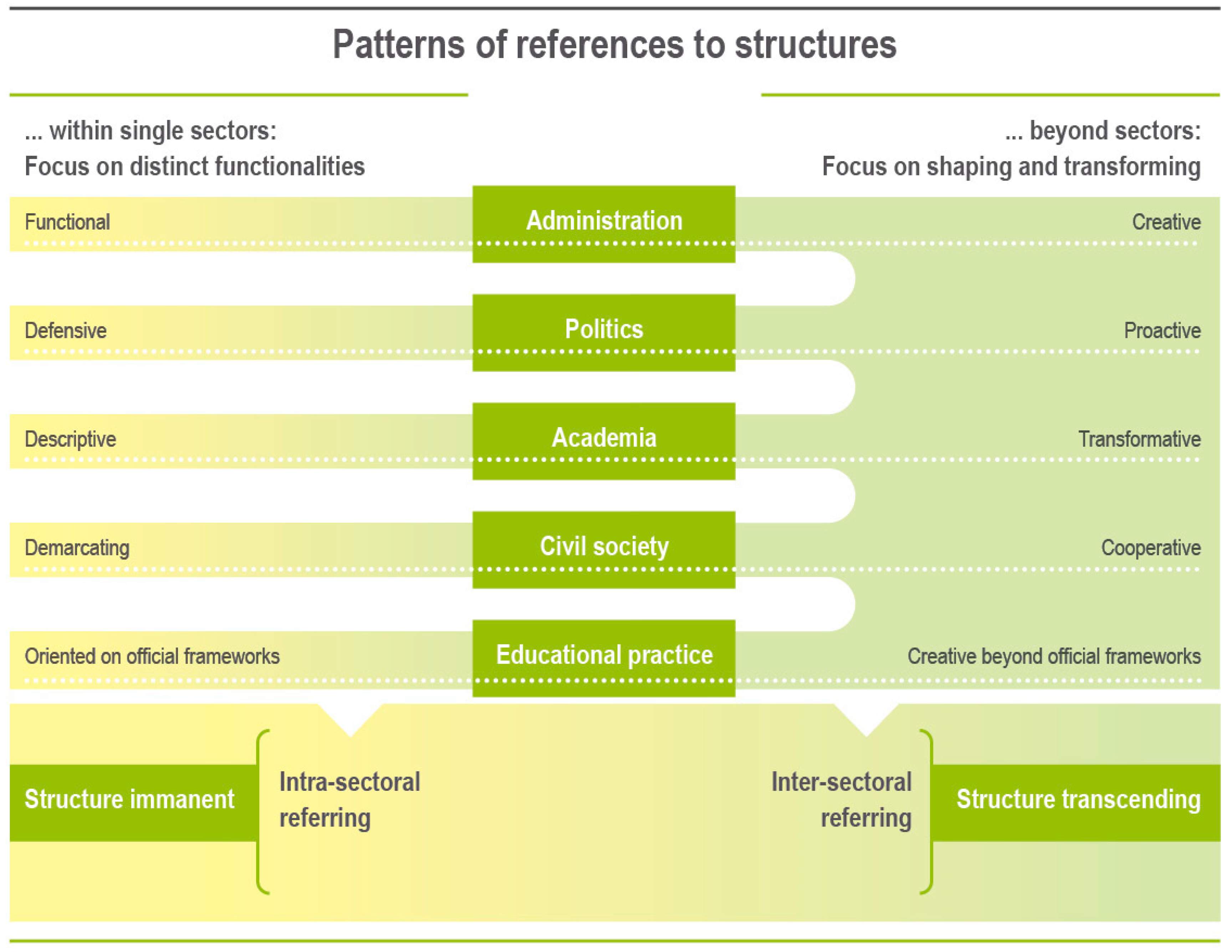

All actors participating in our focus group discussions, regardless of their sectoral background, showed that they already realize specific forms of boundary work toward the other sectors. Summarizing the results, we could identify differences in regard to how the actors referred to their own and other structures that can be captured in the differentiation between an intra-sectoral demarcation approach and an inter-sectoral network approach (see

Figure 2). On the one hand, actors who argued most for intra-sectoral positions claimed the potential and limitations of their own organizations, routines, and practices. This pattern of structure-immanent coordination of action meant that the actors worked effectively, with experience, and functionally within their specific organizations and sectors and, therefore, defended them against the aspirations of actors from other sectors. On the other hand, actors who argued for new ways of networking between various sectors searched for expanded cooperation and creative solutions in scaling ESD. Their coordination of actions opened up to a pattern that can be understood as structure transcending, which means that they actively tried to transform or even transcend given routines and structures. As a result of the summaries and comparison of individual positions in each sector, we developed a heuristic for the positioning of actors between intra-sectoral and inter-sectoral.

4. Discussion

What does the identification of distinct references to structures as a crucial differentiation mean for the coordination of actions within the framework of the governance of the UNESCO GAP on ESD and beyond? We were able to show that ESD actors in Germany realize their boundary work very differently and also coordinate their activities in various ways. We found patterns among all actors that show how they position themselves in terms of their references to structures. We systematized these into a heuristic with differences for each sector bearing in mind that the management of interdependencies between different actors and sectors is at the core of governance processes. We now discuss and theoretically contextualize the ideal-typical patterns for each sector to further explain how the characteristics are embedded within the sectoral logics and to understand what challenges the different actors face when scaling ESD.

The cases of

administration are theoretically underlined by the figures of classical and political civil bureaucrats [

47,

48,

49]. The classical bureaucrat “operates with a monistic conception of the public interest—the ’national interest’ or the ’interest of the State’. He believes that public issues can be resolved in terms of some objective standard of justice, or of legality, or of technical practicality” [

49] (p. 259) and for this reason distances himself clearly from the expectations of other actors. This classical form of bureaucracy represents a democratic achievement because its core principle lies in the rational application of procedural rules and laws and reduces the risk of favoring or disadvantaging individuals by irrational arbitrariness. Political bureaucrats, on the other hand, are more oriented toward a pluralistic conception of public interest, accept the existence of conflicting interpretations of the common good and conflicting group interests as an integral part of modern societies, and assess the acceptance of the influence of political groups on the decision-making process as legitimate (ibid. p. 260). Political civil servants favor and defend their own (i.e., civil-society-prioritized) political strategies and political advantage (ibid.), despite respect for the legitimate legal bases. “Whereas the classical bureaucrat is ’procedure oriented’ or ’rule oriented,’ the political bureaucrat is ’problem oriented’ or ’program oriented’”(ibid.). It is particularly striking that some of the creative patterns in the focus group discussions could be found with administrative actors who had years of experience with ESD. For example, on the local level in many cases, local administrations provide positions for ESD actors that had been working in civil-society organizations for a long time [

50] (p. 173). In contrast to this, actors whose patterns of argumentation showed a functional administrative pattern were only briefly entrusted with ESD.

Politics is crucial in decisions on long-term perspectives and structures for ESD. Which side of the spectrum the political actors moved on, or in other words, if they referred to existing structures in order to justify a lack of commitment in the field, or if they created new structures for more adequate implementation and scaling, depended largely on the political value they attributed to ESD. Traditionally, concepts such as ESD are of political value if they generate “additional approval values in public advertising and image building” [

51] (p. 72). Further, the concepts are valuable if they aid in reducing expenses or create revenue (e.g., as a regional factor), and if programs entail additional funding. Against this background, ESD does not coincide with the interests of political decision makers, as it takes time to convey the concept and is fairly limited in reducing expenses. Yet, Brüsemeiste considers whether one of the greatest achievements of such approaches is not approval in image building or in monetary value but in the fact that they “carry the idea of integrative problem solutions into a branched network of strategic and operative organizations” (ibid.). While political actors interestingly do not refer to this achievement but discuss ESD in terms of individual or traditional value, an “indirect value” is discussed by other participants in the sense of ESD as a motor for networking within the administration, allowing a more integrated way of coping with challenges and, therefore, modernizing the administration. Concluding the findings of the study, it can be said that the involvement of political actors in the bodies of the GAP in Germany is not a success in itself. If they do not recognize the political value of ESD, which goes beyond individual ambitions and traditional understandings, they can even hinder the opening up of structures. How to assess and convey the indirect value of ESD beyond political expectations is an open question.

The argumentative patterns in the

academic sector can be contextualized against the background of the basic orientation of research regarding accelerating sustainability challenges. In general, the generation of scientific knowledge is based on specific rules that guide the processes of scientific knowledge production in comparison with other forms of knowledge. Scientists operate in highly complex fields, and their outputs “are characterized by uniqueness” [

52]. The ideal-typical scientific patterns of the focus group discussion can be interpreted against the background of the current debate about the self-positioning of researchers in view of major societal challenges [

53]. On the one hand, there is an image of researchers who are critical regarding a scientific engagement with societal challenges and only want to describe and analyze them or make them the subject of empirical studies, which is deeply rooted in a positivist understanding of science and the closely related ideals of value-free research (ibid.: 24). For Strohschneider, a separation of the broader systems of politics and science is highly functional [

54], and for this reason academia has to be distanced from societal expectations. Research that is in the service of social change processes loses its autonomy, runs the risk of instrumentalization, and no longer focuses on scientists’ fundamental curiosity (ibid.). It loses critical distance to societal actors and dynamics, can be reduced to a problem-solving scheme (solutionism), and the mixing of scientific expertise and political action leads to a non-democratically legitimized expertocracy (ibid.). On the other hand, in the face of escalating sustainability problems, scientists are encouraged to conduct transdisciplinary research processes [

55] and become more involved in conflict-laden transformation processes in the sense of transformative research [

56], solution-oriented transformational research [

57], or catalytic science [

58]. According to different authors, researchers should not only observe and analyze social transformation processes but also, together with non-scientific actors, actively contribute to overcoming sustainability problems. The juxtaposition of the two patterns resulting from the focus group discussions can be interpreted as a clear picture of the tensions scientists currently face while moving between these different expectations vis-à-vis academia.

Civil society(s) are described in a very diverse and vague manner in the theoretical debates [

59]. Nevertheless, there are similarities in the description of the representatives of civil-society organizations [

60,

61], which show potential for democratization processes, for example, in “protecting the private sphere from attacks of the state and thus securing a private and social space” [

60] (p. 449). Civil-society organizations continue to monitor and control state power, thereby forcing the state to assume specific responsibility (ibid.) and represent common interests. To what extent these common interests are also oriented toward the common good remains an open question in the literature, as precisely because civil-society organizations are not democratically legitimized, they do not necessarily represent public interests but rather particular interests (e.g., in the case of foundations). Nevertheless, most of the civil-society organizations engaged in ESD in Germany care for the common good, such as the support for more sustainability. The demarcating pattern of civil-society representatives in the focus group discussion refers to this potential for democratization and argues against the background of their specific role as (common-good) lobbying organizations. Following the cooperative pattern, actors cannot perform this function intensely. However, the change in the relationship between the state and civil society is important for the success of scaling ESD in Germany, as civil-society organizations serve as crucial non-formal learning partners for formal learning organizations [

62,

63]. Nevertheless, the argumentative patterns of civil-society representatives, in particular, could not be clearly assigned to a pole but oscillated from one pole to the other. Some actors explicitly adopted different roles for their respective arguments—e.g., representative of a civil-society organization or representative of a specific GAP body. The results of the focus group discussion reflected that cooperating civil-society actors may have to face the particular challenge of safeguarding their critical role in the policy process, while demarcating civil-society actors may benefit from a broader view of the potential of joint political processes.

In the argumentative patterns of

educational practitioners, the logic of the individual educational areas came through most strongly. In the school education sector, for example, the educational practice of recent decades has seen an increase in the scope of action in the day-to-day implementation of ESD, which, in their roles as teachers, they are unable to use due to structural limitations. Heinrich [

64] points out the tensions faced by teachers in that their autonomy in terms of content is only of limited use to them, as this is regulated and controlled to an equal extent. Summarizing and understanding the different positions for the whole sector, trying to put the different educational areas aside for a moment, Maack criticizes the frequently encountered statement that content-related ESD work is made possible solely by financial resources. The actual good practice, which educational practitioners implement on their own initiative, can be easily overlooked and a direct "connection between financing and implementation of ESD" [

65] (p. 130) is reproduced. A dependency on funding as an argumentative strategy also means that they do not understand themselves as shaping actors, which is paradoxical, because educational practitioners are significant actors in shaping the domain of practiced ESD. At the same time, aiming at pointing out the shaping quality of educational practitioners should not mask structural limitations such as funding. According to Maack, the focus is above all on reflexivity as the necessary basis for implementing ESD: reflexivity is crucial for the professional teaching of sustainable thinking and action as well as for promoting the development of change competencies among learners [

65] (p. 157). In relation to the results of the focus group discussion, reflection can also be understood as a tool for dealing with the differing requirements, which arise from autonomy and orientation on framework policy guidelines, for educational practitioners in implementing good practice.

The overall

distinction in structure-

immanent and structure-

transcending patterns showed two types of boundary work. The one pattern of boundary work was mainly in regard to demarcating the representative’s own organization from other organizations and sectors with their expectations. This is functional and effective for fulfilling respective tasks in societal sub-systems of highly differentiated societies [

34,

66]. Through their actions, actors who followed these patterns facilitated decision processes and contributed to efficiency not only for an organization’s own goals but also for scaling ESD within the specific organization. Particularly through their specific positioning in the respective organizations and their high level of knowledge about the organizations and associated practices, they demonstrated a vast knowledge of existing structures, which in the end is the foundation for developing new structures. The other pattern of boundary work was in regard to bridging different organizations and sectors through a networking approach and the search for new structures or spaces for negotiations [

30]. For actors who preferred this type of boundary work, it was crucial to gain knowledge about what is important to the other participants in the cooperation process and how they can bring together supposedly different interests as part of a compromise. These actors professionalized themselves through their closer coordination of actions in the multi-actor governance networks for scaling ESD. Both patterns of boundary work showed differences in the actors’ strategies for coping with the complex tasks of scaling ESD and are equally relevant. Nevertheless, it is important to note that the resulting strategies can be used for different tasks and at various times in a distinct way.

Altogether, the coordination of actions and self-location in the overall discussions on scaling ESD sometimes seemed ambivalent: especially civil-society actors were inconsistent in their preferred pattern of argumentation, educational practitioners located themselves diversely, and clear mutual expectations were not always recognizable for all actors. Ambivalences in their explicit argumentation and implicit boundary work revealed their struggle to find a firm strategy and to consciously use specific positions within the policy process. One main conclusion from the results of this study is that it should not be the aim to be positioned at one side of the scale or the other. On the contrary, the aim could be to develop the capacity to recognize and reflect different opportunities to act in multi-actor governance networks and, based on this, to choose between different argumentations and strategies. This strategic movement between the poles to fulfill a specific task remains a significant challenge for all actors, which needs self-reflection to reach its potential. In the search for practical implications, the heuristic can, therefore, primarily contribute to a self-enlightenment of actors—of an awareness of typical patterns that can emerge while working for the scaling of ESD—in the sense of a "reflective practitioner" [

67]. Reflection is a key factor when working in sustainability governance networks [

35]. Additionally, creating relational agency as capacity can provide an adequate knowledge base for reflective practitioners. Both sides revealed the potential to develop a relational agency [

68,

69,

70] in the sense of more pronounced reflexivity about the own organizational functions, rationalities, and behavioral patterns and a greater understanding of the perspectives of other sectors. Relational agency is a pivotal capacity for multi-professional cooperation in education, where boundary work takes place [

68] (p. 42). It is based on knowledge work: as the actors employ different sets of knowledge and conceive problems against the background of their specific institutional purposes, it aims at learning how to align each other’s interpretation of the common problem and gain knowledge of what is important to other professionals regarding the problem they are trying to address. A mutual understanding of complex problems (such as scaling ESD) facilitates the search for appropriate solutions (ibid.).

Scaling ESD in and through multi-actor governance networks can benefit from this relational agency, and both types of boundary work can contribute to relational agency. Nevertheless, relational agency does not predict whether the coordination of action actually contributes to new structures for multi-stakeholder governance or if it instead stabilizes the existing structures and decreases intermediate room for negotiation. If actors go beyond their familiar logics but interpret others’ institutional sets of knowledge incorrectly, they could provoke misunderstandings or even conflicts. Transparency, translation, and mutual mediation among the different sectors were demanded for a successful transformation process but only realized by some actors within the focus group discussions. What is important here is the reflective awareness of their specific way of boundary work, which is based on knowledge of the peculiarities of their own organizations and structures and actively seeks an understanding of the other organizational rationalities. A general impression emerged that more and more actors were leaving familiar organization-related and structure-immanent logics while trying to scale ESD on the way “From Project to Structure.” Actors who have been involved in scaling ESD for a longer period of time were tentatively more on the side of inter-sectoral/structure-transcending positions. The task for ESD is to organize inter-sectoral cooperation structures and, thereby, open up space for questioning and reflecting on the actors’ own organizational and sectoral logics, sometimes even breaking with these.

The

methodological limitations of this study include the fact that the discussion processes within the focus groups are not necessarily generalizable as it is the case with most qualitative research results. Still, the results revealed different patterns that can be connected to the governance of ESD in Germany. Even if the figure implies the risk of oversimplifying the highly complex interaction processes and making them too one-dimensional, it still exemplifies the typical patterns of the actors in their references to overall structures. Additionally, although the method of focus group discussions claims to reconstruct group processes, this reconstruction is to be understood as limited: the discussions were artificially created and influenced by the researchers in composition and content. Also, some aspects that are prevalent in the working world, such as digital communication, cannot be captured. In addition, the actors who were put together into sectoral groups could not share a group discussion, because the allocation followed the educational areas, nor was there a common discourse space among the governmental bodies. The emphasis was not only focused on the explicit arguments of the actors but on the implicit knowledge that was made visible in the concrete negotiation processes in situ during the focus group discussions. The following aspect should also be mentioned as a limitation to our methodological approach: we use the theoretical concept of implicit knowledge as a foundation to grasp the implicit level of coordination of actions. At the same time, analyzing the data with a thematic qualitative text analysis limits somehow our possibility to investigate the implicit knowledge of actors working in the different bodies of the GAP in Germany. Even though the qualitative text analysis is inspired by the hermeneutics, there are some differences to reconstructive-hermeneutic approaches: the depth of analysis, the degree of dealing with linguistic-communicative phenomena, and the different weighting of deductive and inductive categories in the analysis process. Our data analysis was mostly informed by a deductive moment and did not focus primarily on a linguistic-communicative level [

71]. Other methods might be more appropriate to examine implicit knowledge in future studies (e.g., documentary analysis or objective hermeneutics) or habitual knowledge (e.g., participant observation).