1. Introduction

It can be assumed that with good public policy conditions, i.e., sustainable public policy conditions, the achievement of a sustainable net benefit may be enjoyed by society in the form of an optimal and possibly long-term solution to a specific public problem. A relatively permanent solution to a particular public problem can be seen in terms of the sustainable value (net benefits) for society and that the “carrier” is sustainable public policy (e.g., a specific sectoral policy). At the same time, a sustainable public policy is one that is well-designed, effectively implemented, and well-enforced. A key factor for achieving sustainable value as a result of public policy is public policy timing, although this is not the only influencing factor. This term refers to the ability to address matters related to public policy at exactly the right time.

Public policy timing is a recent, completely new, little known, and poorly recognized theoretical idea/concept in public policy shaping. This study presents the issue of public policy timing in the context of the postulation of using a balanced approach in the creation and implementation of public policies.

The first part of the work establishes the role of public policy timing and its significance in various economic theories (such as regulation theory, the concept of adaptive public policy, and the theory of policy timing based on the concepts of option value and transaction costs of the political process). Next, an attempt is made to create a more comprehensive and coherent theoretical basis for the purpose of analyzing the importance of timing in applied public policies. The approach of methodological pluralism is adopted here, which allows us to reach for various cognitive inspirations that have been borrowed from numerous theoretical approaches. In turn, the second part of this work refers to the selected real sector policy, i.e., the Polish health sector policy. Here, an attempt is made to answer the question of whether the approach to shaping this particular sector policy is in line with the concept of public policy timing, i.e., whether, and if so, to what extent the issue of public timing is taken into account.

The methods used in this work are primarily deductive. A general concept of “public policy timing” is built and used here, although to a limited extent, i.e., taking into account the concept of adaptive public policy to discuss Polish health sector policy. Referring to the results of empirical research only serves as an exemplification and illustration of the deductively derived theoretical concept of “public policy timing”. Contrary to appearances, no inductive method is used in this work, meaning that no generalizations are derived from the information material collected during the empirical research. The only generalization that can be derived concerns the nature of Polish health sector policy, namely whether it is adaptive or not adaptive in the context of the “public timing” factor.

Section 1 presents the state of the theoretical thought on the issue of public policy timing, which constitutes the basis of creating and formulating the concept of public policy based on public timing. This means that within the framework of the concept outlined by the authors (see

Section 2), the following points are presented: the point of implementing a policy closely linked with the so-called public policy timing; the results that can be expected from the application of such a policy; and the explanation, using three time perspectives, of why the inclusion of only two instead of three time perspectives in the process of public policy does not give assurance that the public (social) interest will actually be realized and not only the interest of the ruling party/coalition. In line with the assumed concept of public policy,

Section 3 features the preparation and description of a way of examining Polish policy regarding public hospitals. The research results are, accordingly, shown in the form of tables in

Section 6. The same section also describes the results obtained with the approach practiced by decision-makers in Poland regarding the creation and realization of policies in the public hospital sector. The study here is preceded (in

Section 4) by a concise presentation of the systemic context, which allows for better insight into the specificity of the healthcare system in Poland.

Section 5 contains the materials and considerations necessary to establish the importance of the time factor in the process of creating and implementing Polish policy regarding public hospitals. Finally, in

Section 7, conclusions are formulated concerning the approach practiced by decision-makers in Poland regarding the creation and realization of public policy in healthcare and public hospitals in the context of the role of timing in public policy.

2. The State of the Theoretical Thought Regarding “Public Policy Timing”

The issue of timing in public policy is not shown in the economic theory of regulation or in its positive or normative approaches. This also applies to ongoing discussions in the economic literature on proper regulation. There are two key issues in any regulation. The first is an attempt to substantively justify the reasons for adoption, which relate to the set of public policy objectives or result from the analysis of the implementation of public reforms or market mechanism failures. The second is to indicate which legal and economic tools, principles, and mechanisms offer the greatest chance of achieving regulation efficiency or the optimization of the regulation’s goals. The issue of timing remains in the background and works as a default, which is best seen in the context of proper regulation. Of the numerous definitions of proper regulation, the timing subtext arises fairly clearly from the definition [

1], according to which proper regulation is well-designed, effectively implemented, and appropriately enforced, and if the regulation meets these conditions, it provides the greatest net benefit for society. It is not mentioned here, but it seems that proper regulation is of a procedural nature and that all of these conditions, i.e., process phases, take place in time and must be met in proper time for the greatest net benefit to society.

Public policy is closely related to regulation in legal terms and is connected with the ideology of the guaranteeing state. In the legal analysis of the obligations of public authorities, guarantees are understood to be dynamic, taking into account the interests of the beneficiaries of the system that supervise the functioning of the said system. For example, the Constitution of the Republic of Poland imposes an obligation on public authorities to ensure equal and fair access to publicly funded healthcare services. “Ensuring” is understood as a guarantee of equal and fair access to healthcare services financed from public funds, which must include not only the creation of a legal framework for the functioning of the public health system, but also active and dynamic control, as well as supervisory activities [

2]. It is obvious that if the control and supervisory activities are to be dynamic, they must not only be appropriate, but also carried out at the right time and in the right way. The assurance by the regulator of an appropriate environment for conducting active control and supervision activities includes identifying and developing legal and economic tools, as well as the principles and mechanisms that provide the greatest chance of obtaining effectiveness and efficiency of control and supervision. It may turn out that for their completion or improvement, it is necessary to observe the real behaviors of regulated entities under the new/modified health system, and to analyze and evaluate the effects of their compliance with the intentions and intended aims of the regulator. Service providers belonging to the same public healthcare subsector, e.g., public hospital care, despite functioning in the same legal environment and period, may exhibit quite different behaviors and may result in significantly different economic, social, and health effects. This also applies to other entities within the system, such as local government units, which, on the one hand, conduct a decentralized health policy and act as a regulator toward the medical entities that they own or co-own, yet, on the other hand, are subject to statutory regulation themselves in order to direct their behavior or achieve the desired change in behavior toward subordinate medical entities. One example is the Polish regulation that increased the financial responsibility of local government units for losses incurred by subordinate medical entities, which is thus expected to lead to a change in the behavior of local government units relative to subordinate (unprofitable) medical entities [

3]. This may lead to a further observation that it is necessary to track and coordinate public policy timing with health policy and for specific healthcare subsectors, such as public hospital care. This observation relates to the issue of adaptive public policy.

As part of the theoretical approach to adaptive public policy, an attempt to associate timing with public policy was presented by Koehler [

4]. The author posed the following question: Can the development and implementation of public policy be improved by closely tracking and coordinating time with the policy of a regulated sector? Such an association was attempted based on the assumption that the asynchronism between the political process and the regulated sectors or activities may cause unintentional disruptions in the pace of economic change and development, and thus undermine the original intention of the regulatory policy or activities. In addition, such events can lead to unexpected future disruptions. That is why “a policy approach is needed that adaptively ties the right mix of resources and regulatory activity to the timing of particular stages of economic development or growth associated with a particular industry” [

4] (p.99). In the issue of adaptive public policy, problems with determining the right time in public policy timing were examined using a new theory based on the concepts of “time-ecology”, “developmental change in time”, and “temporal signature”. The author emphasized that the indicated approach may apply to various organizational issues and may be related to time in various areas of the economy. The full range of space–time network linkages in cluster government and self-government authorities, namely the health service industry, creates an interconnected unique system of ecology among political, economic, and other areas, covering a clear time perspective in which the advantages of resource use and delayed responses of participants to ongoing changes in the industry’s environment are considered. In such a system, there are more or less intense and often complex rhythmic impulses that occur in parallel or in a punctual manner, affecting one another on a number of time scales flowing into the future. Each organized entity in the public healthcare system exists in its own past, present, and future in a unique way, possessing its own “temporal signature” that determines the position of the object in time and which is a detectable phenomenon. External bonds mutually affect organizations by changing the dynamics of development and growth and the effects achieved by the organization. The whole process, in the context of this study, takes place in the combined adaptive landscapes of public authority or the health services industry.

At this point, it is important to add that the temporal signature of a particular medical entity could be obtained using the benchmarking method for healthcare providers and is expressed in the form of a benchmark, which, by its nature, positions the hospital relative to other hospitals in time and can cover various organizational issues and the effects achieved by the facility. As part of the benchmarking study, it is also possible to use the acquired data and information resources to detect distinguishing features of profitable or unprofitable public hospitals as a unique system in the cluster of public authority vs. public hospital care for the purposes of making adaptive health policy decisions. These are some (proprietary) suggestions for capturing the temporal signature and the unique entity in a given period within the “public authority/public hospital care industry” cluster.

In the economic literature, theoretical thought combining public policy with the timing factor has also been considered by other researchers, but this thought is not yet fully developed. It is reflected well in the work of [

5]. Every public authority, whenever making a political decision, must ultimately decide on three separate issues, namely the choice of policy instruments, the setting of the levels of these instruments, and the timing of their implementation. However, in both theoretical and applied policy analysis, the time dimension of policy making is often ignored or simply treated as an exogenous event in relation to the rest of the policy formulation process, i.e., that policy timing is not an integral part of the public policy process.

To be precise, in the economic literature, the issue of public policy timing is highlighted, but mainly in terms of formal deadlines, negotiating (“playing for time”), and timing for communicating. Timing has an impact on formal public policy decision-making processes in specific jurisdictions. However, the right time to communicate with decision-makers about new public health policies (e.g., in the field of hospital care) also depends on other current problems and the likelihood of strong support or opposition to the policy [

6]. In turn, the analysis of “playing for time” suggests that negotiations on divergences, and in particular legal regulations, occur not only with time, but also in the case of negotiations for the harmonization of legal orders from different countries (e.g., the European Union (EU) and its member states) and, perhaps above all, concern for the unity of time [

7].

Mittenzwei, Bullock, and Salhofer [

5] argue that in the literature devoted to the problems of optimal time in politics, it is often thought (e.g., [

8]) that a change of policy is irreversible. By its very nature, politics can change, and policy-makers often make use of this fact with the regular introduction, changing, deletion, and reintroduction of policies. Researchers have formulated their own theory, where the central element is that “governments balance the costs of delaying policy reforms against the benefits. Costs are in the form of welfare losses, brought about by delayed adjustment to changes in the economic and political environment and by the costs of the political process that accompany policy changes. Benefits of delaying policy reforms stem from receiving better information by waiting” [

5] (p.583). Here, the authors would like to add two observations of their own. First of all, what has not been said by the creators of this theory comes to mind, namely the default assumption that in the process of preparing political reform, every piece of relevant, cognitively valuable, and already existing information is used. Secondly, in light of the combination of this theory with Kohler’s concept, better information can be obtained by detecting the temporal signatures of participants in the public hospital care system, as well as the unique phenomena associated with the system (e.g., the phenomenon of profitable public hospitals under systemic conditions determined for a given time). According to Mittenzwei, Bullock, and Salhofer, the ability to wait before making a decision is very valuable when decisions are made in conditions of uncertainty, and, as time goes on, more and better information appears. The value of waiting for information and the costs of changing policy both shift the balance in the political economic equilibrium and cause sporadic policy changes.

To sum up, in terms of the neoclassical theory of economics, the concept of timing as an important issue has been recognized in the area of the negotiation and communication of new public policy. The new economic theoretical thought combining public policy with the factor of public policy timing is shaping the theory of policy timing. In general, public policy timing is an integral part of the public policy process and is explained in different ways through the prism of a perspective inherent to the formulation and implementation of the so-called adaptive public policy, or through the prism of the value of the ability to wait for better information before making decisions in conditions of uncertainty. Both approaches seem coherent and logical. In the concept of adaptive public policy, it is crucial to detect the temporal signatures that carry better information and unique phenomena in the system found in a given public healthcare system. This better information, combined with the ability to wait for it, has the benefit of delaying political reform (to avoid frequent policy changes and the irreversible costs of policy change). In addition, due to the recognition of the role of timing in the formulation and implementation of public policy timing, leading to the acquisition of better information, it is possible to formulate more accurate regulation related to this policy, which has the characteristics of good regulation. Moreover, considering the legal approach to the regulations related to public health policy, it should be emphasized that the obligation of public authorities to provide active control and supervision within the public health system is clearly combined with the ability to perform appropriate control and supervisory activities in the best possible way and at exactly the right time.

3. The Concept of Public Policy is Closely Linked to Public Policy Timing

The concept of public policy is closely linked to public policy timing. We wonder whether one can improve—and, if so, how—the development and implementation of sectoral public policy by including time treated as an endogenous event in the process of shaping public policy? The most general sense of seeking an answer to such a question lies in the fact that decision-makers have the opportunity to implement sectoral public policy that is better focused on providing the greatest net benefit to society.

This concept claims that a different perception of time, where time is an endogenous event and not an exogenous event in public policy making, changes thinking about methods for building better informed policy (i.e., evidence-based public policy decision-making). The expected effects of implementing a better informed sectoral policy are positive, i.e., those based on the recognition of reaction time intervals (taking action) in various types of industry participants, the reasons for too late reactions compared to those expected by decision-makers, as well as those contrary to their intentions. The practical use of this knowledge, by developing and implementing a complete set of appropriate measures to prevent or eliminate the occurrence of excessive delays for various participants in the sector, is also important. These are mainly economic and social factors.

Economic effects relate to the rational operation of the system (rationality of resource management), such as:

Increasing the resilience of the regulated sector to unintended disturbances, leading to unintended disruptions in the pace of economic change (e.g., scale and organization of health services) and economic development (e.g., due to poorer public health), thereby undermining the original intentions of policies or regulatory actions (assuming that the policy is really in the public interest.

Reducing the risk that such unintended interference will lead to unintended future disturbances in the pace of economic change and development.

Occasional changes in sectoral public policy, which entail reducing the costs of introducing, changing, deleting, and reintroducing specific sectoral policies, leading to saving costs of the regulated system (e.g., public health system), reduced waste of public funds allocated to the operation of the regulated sector, and more funds remaining in the system to achieve the main objective of the sectoral policy.

Social effects relate to the main objective of sectoral policy, as well as to social rationality, such as:

Ensuring equal access to goods produced in the sector when financed from public funds, or at least equal opportunities to obtain such access.

Maintaining or increasing the usability (quality and scope) of goods financed from public funds produced in the sector.

In addition to these effects, a political side effect may occur, i.e., ensuring or strengthening public support for a given public policy.

The concept of public policy is closely linked to “public policy timing” and has three different time perspectives in its field of vision:

The first perspective concerns the annual cycle of the public budget (formal and administrative deadlines for the planning, preparation, and implementation of budget expenditure).

The second perspective concerns the cycle of exercising public authority, determined by the time frame of general elections.

The third perspective concerns the occurrence of time asynchronisms between the course of the public policy process and the course of processes in the regulated sector, as well as between public policy activities and those undertaken by sector participants.

By associating all three time perspectives with one another, a balanced time perspective can be created for the public policy process.

The first and second perspectives create exogenous events for public policy that are not influenced by decision-makers, but instead determine the quality, manner, and duration of the policy. The implementation of expenditure related to policy development and implementation must take place within a rigid bureaucratic framework of the annual budgetary cycle, and, in addition, the term of office of public authority may induce political decision-makers to be guided by more rational political action, achieving rapid, preferably spectacular success, even if it is economically unjustified. The rationality of political action is dominated by the interest of maintaining or gaining political power, which is typically the interest of the dominant ruling party. In the context of rational political action, the time perspective is determined by the calendar of general elections, i.e., the cycle of exercising power by the ruling party. In practice, policy principles, including health policies, are designed in such a way that their use is either short-term or long-term, but the period of validity of government policy is usually limited to the term of the government [

9]. The rationality of political action does not have to be closely associated with economic rationality, or be in the public or social interest. Even Shiffman [

10], in a study of the phenomenon of setting agendas in health policy, challenged the assumptions that health problems appear in political programs only through rational consideration and the careful consideration of evidence. However, the need to include in the public policy the schedule set resulting from the state budget cycle and the public election cycle should not justify the creation of the poorer quality sectoral policy from the point of view of ensuring public interest and economic rationality. The third time perspective, in which time is an endogenous event in the process of creating and implementing public policy, creates the chance for achieving and implementing better quality policy. It is a time perspective for such a policy that fits into the idea of evidence-based public policy. In this perspective, the tasks in the process of sectoral policy based on public policy timing are as follows:

Recognizing and explaining the causes of the indicated time asynchronism.

Determining the economic consequences of the delayed reaction of the entities implementing public policy on the outcome of actions taken by the entities of the regulated sector.

Determining and developing adequate means of leveling the response when delayed too long (i.e., determining whether economic regulation is sufficient and which of its forms are to be employed, if it is necessary, as well as what legal regulation is needed).

The components that make up public policy timing are the temporal signatures (time structures) of the entities in the system, along with their external linkages, determining the best time to make decisions and act (keiretsu), and the ability to wait for better information.

In the process of public policy timing, better information is generated for the purposes of creating a timetable that takes into account the concepts of keiretsu for introducing changes and undertaking actions that modify or reform the functioning of the sector and the formal framework of annual financial budgets, as well as, where possible, general elections (it may be in the public interest to move the schedule outside of the electoral cycle). The carriers of such better information are temporal signatures, which are specific to various types of organizational entities of the economic system (e.g., the healthcare system), as well as linkages between the “temporal signatures” of entities occurring on the active side of the policy (conducting public policy activities) and on the passive side (entities of the sector toward which the policy is conducted). Knowledge about these temporal signatures and their external linkages and related phenomena is unique, because it takes into account the systemic, economic, and cultural contexts in a given country. In addition, signatures, linkages, and phenomena may change due to changes in the functioning of the system. Waiting for such information, provided that the public policy information base is focused on its acquisition and processing, is a method for preparing better quality public policy and better implementation without the risk of frequent changes being the result of unforeseen disruptions. The benefits of delaying modifications or thorough reforms when resulting from waiting for better information are greater than the side effects. Amongst the undesirable effects, there are social losses (resulting from prolonged unfavorable states of access and utility provided by the goods sector) and costs of the public policy process accompanying changes in the policy.

This perspective allows one to find better solutions to a key sector policy problem at a given time. In the economic systems of various countries, the key problems are different depending on the state of development of the system, and they are subject to change over time. Hence, the information obtained will always be unique because it will be focused on phenomena that cause the existence of a key problem.

Restrictions on the effective use of the third time perspective are poorly developed information databases for the process of creating and implementing public policy, as well as a possible lack of will of public authorities to pursue evidence-based policies. Additionally, as Sisnowski and Street [

11] pointed out, obstacles to creating evidence-based public health policy may be the different characteristics between the two worlds of researchers and policy-makers, including their different timeframes, interests, and priorities.

4. The Method of Examining the Case of Polish Policy Regarding Public Sector Hospitals

This study examines the approach to shaping and realizing the policy regarding public sector hospitals in Poland in terms of this policy being consistent with the concept of public policy timing. This means deciding whether the approach practiced in Poland involves the issue of public timing, and, if so, to what scope. The approach was evaluated in terms of three components of public policy based on the concept of public policy timing, as follows:

Temporal signatures (time structures) of providers of hospital services financed from public funds (public hospitals), together with their external linkages.

The appropriate time (keiretsu) for decision-making.

The ability of policy-makers to wait for better information.

The research was based on providing and explaining (according to the specific criteria) answers to the questions set in the area of each component. The sets of questions are presented in

Table 1.

The fundamental objective of healthcare policy in the area of hospital care based on the principles of universality, equality, and free access for all citizens is highly problematic under the conditions of permanent shortages of public funds in the health sector. Since the 1990s, the key problem has been the high and growing level of financial expenditure in the public hospital sector and the financial ineffectiveness of the great majority of the service providers in this sector. The specificity of the key sector is taken into consideration in the study, as well as the specificity of the functioning of the health service in Poland in the aspect of the provision of hospital care financed from public funds, presented in the next section of this paper.

5. Systemic Context for Healthcare Policy in Poland

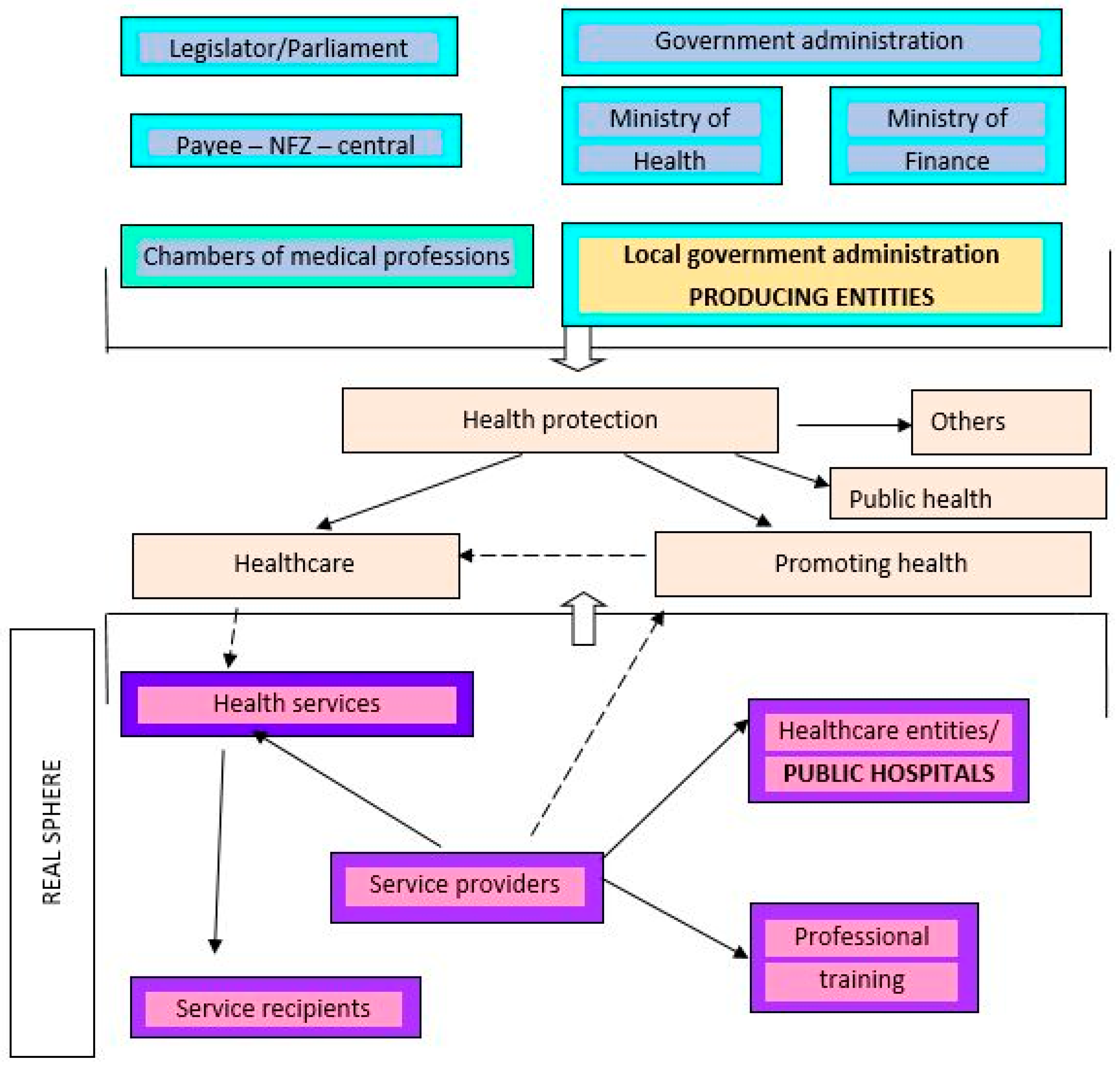

The assumed directions of state policies impact the formation of the relevant organization and the structure of the system (see

Figure 1). Polish regulations that address the functioning of the healthcare system, related to the 1999 reform of that system, are included in the Universal Health Insurance Act. The regulations it contains reflect the accepted fundamental principles of the functioning of the healthcare system, among which the following should be included:

The principle of social solidarity, which means that all of the insured persons, by paying their contributions, create a specific fund that finances the benefits for those that need them. Granting benefits available in the system depends only on the justified health needs of the insured person, and, at the same time, on being equal for all.

The principle of self-financing, which means that both the payee and the service providers should finance their activity out of the obtained revenues, is maintaining financial equilibrium. This principle is also reflected in striving to separate the function of the payer for services from the function of the provider of services. Hence, in principle, the payer, namely the National Health Fund (NFZ), cannot run healthcare facilities, and its relationships with the service providers are regulated through contracts and flat rates for the provided health services. The principle of aiming to ensure equal access to services, which corresponds to, among others, assigning the same range of services to all of those entitled to them, and an equal allocation (understood as ensuring the coverage of the costs of the provided medical services) of the entire range of services in every region (voivodeship).

The principle of economic and deliberate activity.

The principle of self-governance. This principle was subject to rapid modification in light of the Act introduced in 2003 [

12], which resulted in the centralization of the “Kasa Chorych” system and the introduction of a single payer, namely the NFZ.

6. Defining the Role of Public Policy Timing in Polish Policy toward the Public Hospital Care Sector

Activities focused on the public hospital care sector fall within the scope of health policy. The role of health policy is to create development directions for the entire healthcare system, including healthcare that is constantly in the forefront of modern times, such that changes in the environment and the system itself do not surprise its unprepared participants. It should also be remembered that the area of interest in health policy is extensive, and a broad perspective should be used, capturing the instrumental role of many sectors of the economy, since it affects many areas that include, among others, family and child protection policy, agricultural and food policy, industrial policy, environmental protection policy, education policy, employment policy and protection of working conditions, and housing policy.

Determining the legal framework and directions of action in health policy is conducted by the legislative authority, government administration, and local government administration. Each of the links, formulating and creating conditions for action, directly influence the shape and organization of the health sector, including public hospital care. The legislative authority sets the legal framework for the functioning of the healthcare system. Exercising this kind of power includes introducing new legal regulations, but also changing the current law. This area includes, among others, decisions on the broadly understood organization of the healthcare system, decisions on the arrangements contained in the Budget Act, decisions on tax rules—in particular, exemptions and deductions, and health expenditures obtained from the collected medical services—as well as arrangements regarding the amount of health insurance premiums (which are part of the tax). The government administration strengthens strategic functions and limits the functions of day-to-day management by conducting central government administration in Poland, including non-integrated administration in the voivodeship and local government administration. The government administration body in the field of healthcare is the Ministry of Health, which, among other rights, has control rights over other entities operating in the system, but also sets the directions of the country’s health policy. One of the most important roles in the healthcare system, however, is played by local government administration performing the functions of the so-called creating (producing) entities. As the special owner of public entities providing medical services, it accepts responsibility for the incorrect activities of its subordinate entities. The most important requirement of local government units, forming bodies of independent public healthcare facilities, is exercising appropriate supervision over them. In the current legal framework, the principles of supervision are regulated in the Act of April 15, 2011 on medical activities [

3]. The control and evaluation of a health unit’s activity and the work of its manager is carried out, in particular, in areas such as the proper management of property and public funds and financial management, as well as the implementation of tasks specified in the organizational regulations and the statute, in addition to those in the scope of availability and quality of health services provided. What is especially important is the supervision over the financial economy, which is exercised by controlling and assessing its legality, economy, purposefulness, and reliability. On the other hand, supervision over the correctness of property management is carried out through control and assessment, in particular of the use of medical apparatus and equipment, the application for the purchase or acceptance of medical apparatus and equipment, the application for the sale, lease, or rent of fixed assets, or the transfer of such assets to companies or foundations.

This multi-level decision-making has caused the emergence of varied attitudes and behaviors of public hospitals in the activities of hospital medical entities in the face of the changes taking place. An important source of information of the problems undertaken in the framework of health policy is the analysis of activities carried out in connection with the implementation of healthcare system reforms. In Poland, these reforms are usually based on organizational changes in the system, often without touching upon previously diagnosed problems. It is intentionally assumed that new solutions will improve situations (mostly bad economic situations) with which hospitals have had the biggest problems.

An expression of the poor economic situation of public hospitals is the high level of liabilities due to independent public healthcare facilities in subsequent years (2002–2018), shown in

Table 2.

The implementation of tasks adopted by the state as part of health policy is related to the amount of financial resources that can be allocated to maintaining or improving the health of society. Not only are their size and structure important, but also their use by individual institutions that provide health services. The consequences of the reforms introduced and the financial effects of these changes are also significant. There have been many significant reforms in Polish healthcare. In 1999, independent public healthcare facilities were introduced in place of the existing healthcare facilities. In 2005, the place of Kasa Chorych funds was taken by the centralized National Health Fund (NFZ), and, in 2011, the system was further organized by introducing the Medical Activities Act. Each of these changes was accompanied by strong pressure of success, regardless of the degree of preparation for the transformation process. Due to the usually very short adjustment period to the new conditions, additional support for the system was organized. As a consequence, the Polish healthcare system has been repeatedly “deleveraged”, which has clearly influenced the attitudes of the managers of public hospitals and their owners, assuming “tacit agreement” in their activities for further deleveraging of entities and uncertainty as to the future of entities. It should be remembered that the processes of debt deleveraging are basically not conditioned by any real economic, organizational, or medical requirements. In view of the above, the Ministry of Health carried out the aforementioned process of deleveraging hospitals several times. The first debt relief took place after the healthcare reform in 1999, which was when the Kasa Chorych funds were created. The reform assumed that the facilities most frequently visited by patients would receive funding. In order to provide equal opportunities, all hospitals were deleveraged. The treasury took on over 7 billion PLN in debt by doing so. However, hospitals started to get into debt again, and the next stage of healthcare reform was to replace the existing health funds with the institution of the National Health Fund in 2004.

Since 2004, the National Health Fund has been dealing with the pricing and contracting of services in hospitals. Despite such a significant change, an increase in the overall debt of hospitals is still being observed. One of the reasons for this is the change in legal regulations affecting the level of expenditure of public hospitals without indicating specific sources of coverage. The so-called 203 Act, adopted in 2000, was a special one, as it forced healthcare facilities to increase their staff salaries by 203 PLN. Total debt increased rapidly during this period. In 2005, the government adopted the Act on state aid and the restructuring of public healthcare institutions. This enabled public hospitals to take loans from the state budget to repay outstanding liabilities. At the same time, the Act allowed hospitals to write off public liabilities after the restructuring process was completed. Since then, the dynamics of the increase in liabilities (see

Table 3) have clearly decreased, associated with decision-makers refraining from introducing further unannounced changes. Stable working conditions have, however, caused the settling of public hospitals in economic reality.

The data contained in the table above show the effects of the actions taken by hospitals in individual voivodeships and central units (e.g., the Ministry of National Defense and the Ministry of Interior and Administration). The relative stability of organizational and legal conditions and the relatively long period of stabilization have allowed for the implementation of real remedial measures in hospitals that improve their economic results. An important success is the significant change in the ranking of hospital liabilities of the Dolnośląskie, Lubelskie, and Podkarpackie voivodeships, achieved as a result of numerous, often unpopular, actions. The consolidation of hospitals, changes in business profiles, or the transfer of parts of unprofitable activities to other hospitals has resulted in a clear improvement of their economic situation and better ranking. Among the 18 study participants, the aforementioned voivodeships have significantly improved. Dolnośląskie changed from position 1, the weakest, to position 8; Lubelskie changed from 8 to 3, and Podkarpackie changed from 12 to 6 in the years of 2005 and 2017, respectively. This demonstrates the clear need for stable operating conditions and the need to be well prepared for future tasks, i.e., timing, which is jointly responsible for success in planned projects.

Good action means the opportunity to develop and compare the effects of one’s actions with the effects of others. Unfortunately, even during a period of exceptionally stable conditions, no systems of universal information on phenomena occurring in the healthcare sector, catalogues of “good practices”, or systems of warnings about anticipated difficulties have been introduced in Poland. The market environment has encouraged hospitals to make independent decisions (not enforced by the system), resulting, for example, in the process of ownership transformation. As a result, many hospitals have changed their legal form of business, usually to companies with the majority share of local government units. This form was economically justified, because it gave them the right to conduct activities going beyond the system financed by the payer (NFZ). The year of 2011 brought further turmoil to the economic situation of public hospitals, which was normalized by transferring the obligation to compensate the hospital deficit (net losses) to the forming entities, i.e., local government units. This decision was a surprise not only for hospitals, but also for the local government units (LGUs) themselves [

14]. The need for information on the situation of other hospitals and the attitudes of individual LGUs has become extremely important. However, for the purposes of the control and ownership of supervision functions, individual LGUs only have their own information systems or control support tools (or did not have them at all). These systems are not consistent in any way, which absolutely limits their comparative functions. As a result, there has been no available or reliable information collection that would allow rational decisions to be made, either at a given moment or in the future. Only within the framework of scientific research conducted by scientific centers can one find selective or comprehensive studies on this issue. A special place is occupied by unpublished statistical reports based on data covering all voivodeships and data collected as part of an innovative research project carried out in 2011–2015 by the Wroclaw University of Economics [

15]. These studies have identified the distinguishing features of profitable and unprofitable hospitals. Nevertheless, interest in the results of the study [

16] was negligible, on the part of both hospitals and decision-makers. Other interesting research in this area has been conducted only fragmentarily, e.g., in the Łódzkie and Pomorskie voivodeships, which also remains only in the sphere of scientific inquiry.

The need for good information turned out to be necessary at the time of introducing another very important reform—the so-called “hospital network” in 2017 [

17]. The hospital network has been operating since October 1, 2017. The Act introducing this organizational change in the system was prepared in March 2017 and signed on April 2017, and the classification of hospitals into the network was announced on June 27, 2017, without prior information on the planned conditions necessary to be met. Thus, hospital owners did not have enough time to prepare for this change. This means that there was a lack of optimal time projected for hospitals, the so-called timing, with which they could better prepare for entering the network. It is also worth noting that at the time the network was introduced, hospitals were at various stages of economic growth (even if they remained at their profiles, they differed in their efforts to improve their profitability) or were at various stages of economic development (some expanded the range of benefits to ensure better profitability and others changed their legal form). This did not affect the decision to qualify for the network.

Along with the introduction of the hospital network, the method of obtaining funds for hospital operations from the public payer, i.e., from the NFZ, was also changed [

18]. The new method of financing benefits was based on a lump sum covering existing contract performance, but without taking into account the previous numerous so-called oversupplies, i.e., necessary medical services provided by hospitals despite the lack of financial coverage in the contract with the NFZ.

In general, hospitals were surprised by the pace of introduction of the “network” solutions and the shape of the reform discriminating against hospitals that were on a development path (i.e., a path not matching the concept of a general hospital or, otherwise, those operating as commercial companies). It should also be emphasized that the intentions of domestic decision-makers regarding the profitability of contract-financed hospitals are not clear, since they had information on the specific properties of profitable and unprofitable hospitals and information from the hospital environment about the potential negative consequences for hospitals and their patients in the context of the rapid entry into forced legal regulations regarding hospital networks.

As a consequence, the quickly implemented changes have not brought the expected effect so far. The introduction of the network, together with the change in the financing method based on the lump sum calculated according to an algorithm, has not changed the decisions taken in hospitals. With the assumption that by limiting the number of service providers (network of hospitals) and transferring funds at a level that takes into account the current overall performance of services (only services settled with the payer), but without additional incentives, a visible improvement in the operation of public hospitals has not been demonstrated. Public hospitals, especially those that are subordinates to district self-government units, are reporting increasing losses and a higher level of liabilities due. The lack of real preparation for action in the new conditions and the lack of real incentives did not lead to the decision to change in the hospitals themselves. Simple services have not transferred from departments to specialist hospital outpatient clinics, although this was the decision-maker’s expectation. No other explicit changes have been made to improve the efficiency of operations, because another mechanism (the obligation of LGUs to cover the hospital deficit) has not inspired them. The lack of comprehensiveness in the last introduced reform, as well as the lack of time for the proper preparation for the planned changes, has not allowed the most anticipated effects of the reform to be obtained, which are, on the one hand, an improvement in the economic situation of public hospitals, yet, on the other, an improvement in access to services for patients, including the shortening of queues.

The need for public policy timing in Polish policy toward the public hospital care sector is therefore very clear. Its apparent lack means that the ability to access better information has not been developed in public hospitals. Changes in political reforms lead to uncertainty and to an increase in financial risk for hospitals and their owners, which does not create a system of universal information on phenomena in the hospital care sector, and which should be a valuable information foundation in the process of formulating and implementing health policy and developing proper regulation. In addition, the lack of homogeneous systems used to perform the functions of ownership control and supervision in local government units causes constant systemic instability and the permanent dissatisfaction of the system’s beneficiaries, i.e., dissatisfaction of both the service providers and the patients.

7. Results of the Research on the Role of Public Policy Timing in the Policy Regarding Public Hospitals in Poland

The research results are presented in

Table 4.

The research carried out here includes three components of public policy regarding the sector of public hospitals in Poland, indicating the absence of conducting policies based on the public policy timing. Most of the criteria determined for individual components were not met, or only met in part. The only absolutely positive answer appeared in the component “ability to wait for better information” in the second criterion, but since that criterion is of a negative nature, this is not, in fact, a positive result.

The approach used by public decision-makers in policy regarding public hospitals has created several effects that do not bring about a positive contribution to the concept of a policy based on public policy timing. The remaining results are described below.

- 1)

In the period preceding the reform based on “hospital networks”, there were numerous and inconsistent changes in difficult and hardly predictable reforms. They were chaotic, frequent, and undertaken under the influence of current political issues and pressing financial and infrastructural problems in the health system without a clearly defined vision. At the national level, there was no waiting for “better information”, nor was it essentially sought in a methodical and reproducible manner such that it would allow the detection of unique phenomena in given conditions and time. Additionally, at the regional (local government) and local (district and communal) levels, interest in obtaining better information as part of the function of controlling and supervising subordinate hospitals was different. The ability to wait for better information at the national and lower levels has been shown to not exist. This means that the dimension of the optimal time for creating health policy, including in hospital care, was ignored or treated as an exogenous event in relation to the rest of the policy formulation process.

- 2)

As a result, hospitals have been operating in conditions of uncertainty and growing financial risk. This has forced hospitals and their owners to take some specific approaches to solving the general problems of the size, quality, and structure of services versus the hospital’s economic profitability. Over time, hospitals have created their own survival solutions. Scientific research conducted in the environment has led to the detection and transfer of unique information to decision-makers, e.g., the properties of profitable and unprofitable hospitals, which can be treated as better information in the understanding of theories combining timing with public policy. Before the development and implementation of the reform related to the “hospital network”, according to the knowledge of the authors, it was possible to use better information; however, this was omitted in practice.

- 3)

The method and scope of the reform of the operation and financing of hospitals included in the so-called public hospital network were contradictory in light of adaptive policy theory, a policy approach that adaptively links the right combination of resources and regulatory activity to timing for specific stages of development or growth in public hospital care.

- 3a)

Public hospitals that were included in the “hospital network” at the time of the introduced reform were at various stages of development in connection with varied adopted directions and ways of adapting them to changes in the operating environment. These hospitals operated in conditions of uncertainty and growing financial risk. For hospitals that were at a low stage of growth or at a higher level but were not sustainable, this concerns financial and production aspects which are significantly unsustainable (i.e., hospitals did not develop the quality of human resources and/or did not develop their activity to improve the quality of services, poorly responded to the intention of the previous legislator regarding economic rationalization of operations, or did not develop the structure of the assortment of services). However, hospitals that fulfilled the specific requirement of being a four-profile hospital (providing health services in four basic medical specialties: internal medicine, general surgery, obstetrics and gynecology, and pediatrics, as well as in the field of anesthesiology and intensive care) were granted more complete access to public funding. Hospitals that entered a higher stage of development (i.e., those who developed a socially desirable offer of services subject to public funding and the ability to provide these services) found themselves in the so-called trap of strategic surprise as the result of a sudden cut of some benefits financed through a public contract. Additionally, public hospitals that, according to the intention of the previous legislative authority, were transformed into commercial companies with the ownership of local authorities and modernized (with significant investment outlays) were suddenly in a difficult financial situation. The business continuity of these hospitals was threatened by virtually being cut off from financing health services by the NFZ. The omission of the timing factor in the reform related to the “hospital network” led to some hospitals falling into a strategic trap, and this particularly applies to those that previously actively adapted to changes in the environment. This also jeopardizes the effectiveness and efficiency of health policy pursued by local/regional governments, which hospitals falling into a strategic trap are often subject to.

- 3b)

The lack of an adaptive political approach is expressed in the failure to make use of the existing unique information (even at the time preceding the communication of the new reform) on the factors and sources of economic viability in connection with the qualitative elements of the operation of public hospitals and their changes over time, and thus information that could allow for the development of better regulation of the “hospital network” (i.e., information that should not be ignored in regard to the importance of the profitability aspect of hospital medical entities for the health system).

- 4)

Ignoring or not using the already existing “better information” indicates that the approach of the decision-makers of Polish health policy deviates from what is desirable in the theory of policy timing, i.e., the government balances the costs of delaying political reform with the benefits (resulting from receiving better information by waiting).

The introduced reform carries social and economic losses. The resources of hospitals included in the “public network of hospitals” are not better (i.e., more efficiently and rationally) used, the problem of the financial debt of hospitals is growing (only partly resulting from the increased wage pressure in public hospitals at that time), there is a growing negative pressure in hospitals on treating patients not as customers but as a cost to be minimized, and the management’s motivation to improve the economic viability of hospitals without at the same time having a negative impact on changing the perception of the patient has been weakened. These losses could be avoided or reduced by prudent use of the valuable information already available to decision-makers and by consideration of the issue of the economic viability of healthcare entities.

8. Conclusions

The concept of a policy closely linked with public policy timing (described in

Section 2) shows that the timetable that de facto considers only formal timing (the first time perspective) and that resulting from the cycle of general elections (the second time perspective), leads to neglecting the possibilities offered by the third time perspective (i.e., preparing a better policy that is based on business information connected with the time factor, if such is deliberately gathered and used, and not resulting in the waste of public funds, etc., as indicated in

Section 2). Only a timetable based on combining all three time perspectives will be appropriate, and not one, as is the common case in the Polish approach, that is almost entirely dominated by two perspectives that are typically used alone.

The final conclusion is that the time dimension of Polish public health policy creation has been ignored or treated as an exogenous event in relation to the rest of the policy formulation process. There is no political approach that adaptively links the right combination of resources and regulatory activity to timing for specific stages of development or growth in public hospital care. The result is a continuous lack of a long-term (or even short-term) solution to public health problems in Poland.