Abstract

Since the announcement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the need for localization of SDGs has been emphasized. In this context, sustainable rural development is still a relatively undescribed area in the context of using the participatory budget as a tool to implement SDGs. Few countries have introduced legal regulations in practice, enabling the creation of participatory budgets (especially in rural areas), so a multifaceted analysis of a decade of Poland's experience may provide important guidelines for countries considering introducing such solutions, which we consider to be the main purpose of this study. This is the first study covering all communes where participatory budgets (Solecki Fund—FS) were created in Poland during the 2010–2018 period (up to 60% of all), covering both the analysis of the process of creating FSs, the directions of spending and the scale of spending (including regional differentiation), as well as legal regulations and the consequences of including central government support in this mechanism. On the basis of the research, it can be observed that, despite the small scale of FS spending, the number of municipalities using this form of citizen participation is increasing. At the same time, there is significant variation between regions, which indicates the flexibility of the FSs in adapting to the needs reported by residents. The analysed directions of expenditure indicate that the FSs are in line with the SDG objectives related to the improvement of residents' quality of life. It can be concluded that, despite the existing legal regulations, the introduction of the Solecki Fund undoubtedly depends on the political will of the local government's legislative authorities and the willingness of residents to participate in decisions on spending directions.

1. Introduction

The issue of development in rural areas is quite frequently touched upon in literature. As Ellis and Biggs state, beginning in the 1950s, at least six major switches have been observed to have taken place in rural development thinking [1] (p. 437). However, importantly, from the perspective of the article, even back in the 1970s, the World Bank assumed that “rural development is a strategy designed to improve the economic and social life of a specific group of people—the rural poor. It involves extending the benefits of development to the poorest among those who seek a livelihood in the rural areas” [2] (p. 3). The often-cited Moseley also points toward the aspect of improving the quality of life in rural areas: “Rural development refers to the process of improving the quality of life and economic well-being of people” [3] (p. 3). Likewise, in The Cork 2.0 Declaration [4] (A Better Life in Rural Areas) the countries of the European Union emphasized “the need to ensure that rural areas and communities (countryside, farms, villages, and small towns) remain attractive places to live and work by improving access to services and opportunities”. In this context, it can be said that one of the determinants of rural development is the improvement in quality of life in these regions. It bears noting that the core of these definitions is the sustainable improvement of livelihood for rural people. On the other hand, Neumaier [5] maintains that “a lack of social innovation is often one of the strongest restraints of the vitality and further development of rural communities in developed, democratic, capitalist, industrial countries”. It is relevant to mention that social innovations (more about this in Reference [6]) include various processes of public participation [7,8,9]. It should be noted that there are many areas of research concerning rural development which do not pertain to the quality of life [10,11,12,13]. Woods [14] (p. 2) states that one of the main challenges currently faced by rural social scientists seem to be the issues around the sustainable use of resources; the resilience of rural communities to environmental uncertainties; challenges arising from the intensification and reconfiguration of global mobility patterns; critical analysis of the political economies of new strategies for rural economic development based on the sustainable use and management of environmental resources; the redrawing of the contours of state intervention in rural societies and economies including the potential rationalisation of expensive rural public services; and reevaluation of state support for agriculture, conservation, and community development in the context of economic austerity. The purpose of this article is an attempt to evaluate how a specific form of public participation—Solecki Fund—can support the local government in rural areas in achieving SDGs within sustainable rural development (SRD). Solecki Fund (FS) can be considered as a rare (worldwide) form of rural area's inhabitants' public participation, and this paper aims to discuss critical issues connected with the FS application in Poland in the SDG and SRD context. Such analysis can contribute to a worldwide discussion on the impact of participatory budgeting influence on sustainable rural development. The conducted study, apart from explaining the conditions of evolution and use of rural participatory mechanism in the approach to public participation and sustainable development, contributes to the determination of the possibilities and limitations of adapting these actions into the practical implementation of the SRD concept.

One may notice the previously mentioned term sustainable rural development (SRD) in the discourse concerning rural development. Moreover, its place in sustainable development (SD) is a frequent subject of discussions. The 1970s and 1980s mark the points in time when countries and international organisations first started to take an interest in the issues concerning SD [15]. The first attempt to formulate the principles of the development model, later called sustainable development, was made during The United Nations Conference on the Human Environment (Stockholm from 5 to 16 June 1972) [16]. One of the first commonly used definitions of sustainable development has been established by The World Life Issues on Environment and Development (WCED) Commission led by G.H. Brundtland. In the report released by the commission entitled Our Common Future [17], it is stated that ”Humanity has the ability to make development sustainable to ensure that it meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” [17] (p. 16). In the following years, sustainable development (SD) became one of the main concepts behind the global environmental policy [18,19,20,21,22,23]. In literature, the most common stance is one assumed by E. Barbier [24], according to whom “the usual model for sustainable development is of three separate but connected rings of environment, society, and economy, with the implication that each sector is, at least in part, independent of the others” [25,26,27,28]. Of course, the issues concerning rural areas (SRD) did not go unnoticed in the activities and discussions relating to balanced development. Analysing the following year after the Rio Earth Summit, Murdoch noted that ”the concept of ‘rural sustainability’ implies an extensive and complex research agenda.“ [29] (p. 237). The problems resulting from the complexity and interdisciplinarity of SRD were often accentuated [30,31,32,33], and the research areas encompass (among others) land planning, sustainable agriculture development, water management, sustainable tourism, and community participation (concerning the mentioned) [34]. It bears noting that, in this context, SRD is not at all a homogenous term but rather one that comprises a wide variety of disciplines. Boggia et al. [35] maintain that ” in rural areas, development must be achieved to improve social and economic conditions, but it must be sustainable”. Meanwhile, having analysed the goals of SRD, Moseley [3] (p. 24) notices the following: developing the skills, awareness, knowledge, health, and motivation of local people so that they have greater access to productive and satisfying work and participate in developmental activities; securing physical infrastructure and other manufactured capital; establishing effective and equitable organizations and institutions and management systems that contribute to economic development which respects the conservation of natural, man-made, and human resources; upholding and reinforcing formal and informal systems of justice, democracy and governance that promote social cohesion and justice; as well as maintaining and encouraging diverse cultures, traditions, and activities which enhance continuity with the past, the celebration of local place, and local pride.

As of the announcement of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the need for localization of SDGs, understood as “the process of taking into account subnational contexts in the achievement of the 2030 Agenda, from the setting of goals and targets, to determining the means of implementation and using indicators to measure and monitor progress” [36] (p. 6), has been emphasized. It was established that “SDG[s] implementation has to be bottom-up, not top down” [37] (p. 1). At the same time, “[t] his focus on a territorial approach to sustainable development, with its recognition of the key role of local government, as enshrined in the principle of subsidiarity, has been recognised by development partners such as the European Union” [37] (p. 1). United Cities and Local Governments (UCLG) in reports from 2017 [38], 2018 [39], and 2019 [40] note that local and regional governments (LRGs) partake through various undertakings in the realization of SDGs. Among others, attention is drawn toward (essential in accordance with this article) goal 4—ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all; goal 6—ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all; goal 11—make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable; goal 15—protect, restore, and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss; and goal 16—promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all, and build effective, accountable, and inclusive institutions at all levels. One may also notice that reference is drawn here not only to the participation as part of realizing SDG of local governments, NGOs, and other institutional actors but also to the inhabitants themselves [37,40,41,42]. It is also worth noting that the first studies dedicated to this issue have been made during the recent years [41,43,44,45,46,47,48,49]. As an example, Cabannes [49] asserts the utmost importance of target 16.7 of SDG 16 (ensure responsive, inclusive, participatory, and representative decision-making at all levels) and target 11.3 (sustainable human settlement planning and management) in the context of utilizing participatory budget (PB) by LRGs. In conclusion, deliberations concerning development of rural areas must also encompass the analysis of solutions in terms of public participation in public matters using the PB formula.

As of the announcement of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the need for localization of SDGs, understood as “the process of taking into account subnational contexts in the achievement of the 2030 Agenda, from the setting of goals and targets, to determining the means of implementation and using indicators to measure and monitor progress” [36] (p. 6), has been emphasized. It was established that “SDG[s] implementation has to be bottom-up, not top down” [37] (p. 1). At the same time, “[t] his focus on a territorial approach to sustainable development, with its recognition of the key role of local government, as enshrined in the principle of subsidiarity, has been recognised by development partners such as the European Union” [37] (p. 1). United Cities and Local Governments (UCLG) in reports from 2017 [38], 2018 [39], and 2019 [40] note that local and regional governments (LRGs) partake through various undertakings in the realization of SDGs. Among others, attention is drawn toward (essential in accordance with this article) goal 4—ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all; goal 6—ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all; goal 11—make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable; goal 15—protect, restore, and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss; and goal 16—promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all, and build effective, accountable, and inclusive institutions at all levels. One may also notice that reference is drawn here not only to the participation as part of realizing SDG of local governments, NGOs, and other institutional actors but also to the inhabitants themselves [37,40,41,42]. It is also worth noting that the first studies dedicated to this issue have been made during the recent years [41,43,44,45,46,47,48,49]. As an example, Cabannes [49] asserts the utmost importance of target 16.7 of SDG 16 (ensure responsive, inclusive, participatory, and representative decision-making at all levels) and target 11.3 (sustainable human settlement planning and management) in the context of utilizing participatory budget (PB) by LRGs. In conclusion, deliberations concerning development of rural areas must also encompass the analysis of solutions in terms of public participation in public matters using the PB formula.

Theoretical concepts of citizens participation in the activities of public institutes can be found in the works of Arnstein [50], Connor [51], and Langton [52]. The most popular model is Arnstein’s Ladder of Citizen Participation. In this concept, the participation refers to the influence of the “minority” (i.e., part of the local community in our case) on decisions of those in power, while redistribution of power is supposed to (among others) include people who are currently excluded from political and economic processes. The S. Arnstein’s model distinguishes eight types of participation, of which typology has been arranged hierarchically in accordance with the increase in the decision-making power of stakeholders (Table 1). The bottom of this hierarchy includes two rungs of “illusory participation”: manipulation and therapy. The first one mainly covers the inclusion of selected groups of residents into the advisory bodies (such as consultative groups or advisory committees) and educational activities aimed at them. However, such education is just seeming education, while the communication is one-sided and mainly focused on promotional and image activities. The first step towards true participation is the third rung—informing—however, in this case, the communication channel is often one-way and it does not provide citizens with the opportunity to speak their mind or negotiate. Another type of participation—consultation—can only create the appearance of proper participation. This happens when consultations consisting of getting to know the opinions of residents are limited only to gathering information, without taking them into account during decision-making. The last type of seeming participation, which is an example of the symbolic inclusion of representatives of the dominated groups into institutional structures created by dominant groups (the so-called tokenism), is placation. The next three types of participation—partnership, delegated power, and citizen control—are already at the level of a real distribution of power between citizens and those in power. In the case of partnership, responsibility for planning and decision-making is shared through planning committees and conflict resolution mechanisms. Undoubtedly, the functioning of the Solecki fund (FS) matches the “participation ladder” (as a kind of PB) between placation and partnership (nonmandatory form of consultation but mandatory voting results implementation, coproduction [53]). In the case of delegation, it means transferring almost all power over a specific program to residents, enabling them to take actions adapted to their actual needs and expectations. Conflict resolution forces parties to undertake talks and negotiations. Citizen control is an extreme form of participation in which stakeholders take over the control over part of the management activities.

Table 1.

Levels of participation according to Arnstein [50].

Other approaches to public participation were a development, addition, or new look at the observations made. Rowe and Frewer [54] (p. 257) analyzed the concept and forms of public participation, listing about 100 mechanisms. They point to the variety of forms of public engagement [54] (p. 259–263) depending on different mechanism variables (Table 2).

Table 2.

Key public engagement mechanism variables according to Rowe and Frewer [54].

Thus, similarly to Arnstein, they indicate that the degree of involvement of residents can be very diverse, but in their view, it is multidimensional and the types of citizen involvement are intertwined. In contrast, Eversole, describing the classification of types of participation [55] (p. 56), states that the answer to the question “How much influence do the participants have over the outcome of a participatory initiative?” is usually sought. It indicates, among others, International Association for Public Participation (IAP2) Public Participation Spectrum [56] developed by the International Association for Public Participation as a scale “written from practitioner's perspective for use by practitioners” [55] (p. 56). The IAP2’s proposal consists of five levels—inform, consult, involve, collaborate, and empower—that are similar to Arnstein's rugs of the participation ladder (omitting manipulation and therapy). We can describe each type of IAP2 engagement scale as follows [55] (p. 56) [57]: First of all, for “inform”, the main objective is only to inform through web sites, pop-ups and photo galleries, open houses, downloadable resources, newspaper articles. Then, ”consult” aims to obtain feedback on analysis, alternatives, or decisions presented to inhabitants. It can include voting, focus groups, surveys, public meetings, social media monitoring, and discussion and comment boxes. Next “involve” means using the method of direct cooperation with stakeholders throughout the process (deeper than consulting). This may include workshops, community mapping, crowdsourcing, scenario testing, citizen panels, and participatory budgeting. The next type of engagement is “collaborate” hat means recognizing citizens as a partner in making decisions, consisting of taking into account various aspects of problems solved in the joint selection of solutions citizen advisory committees, document co-creation boards, participatory decision-making, and working groups. The last one is “empower”; in this case, the emphasis is on putting the final decision-making process in the hands of the public. The community must be jointly responsible for making decisions and responsible for its effects. The most common forms are citizen committees, decision-making platforms, or citizen juries.

As one can notice, the general public seems to be excluded from collaboration and empowering stages because of procedure limitations and requirements (e.g., the need for the small groups of experts or representatives). This split was noticed earlier in 1988 by Connor in his “new leader of citizen participation” [51]. Connor underlined that only three rugs (proposed by him as education, information feedback, and consultation) are available for the general public [51] and the rest of the rugs is available only for the leaders (joint planning, mediation, litigation, and prevention).

In recent years, Nabathi and Leighninger in “Public participation for 21st century democracy” [58] developed a new look on public participation forms. They distinguished two main groups. The first one, indirect participation, includes (incorporates) voting and donating money. The new concept is that the second group, direct participation, is divided into three forms of participation accordingly to the level and way of empowerment of citizens: conventional participation and thin and thick participation. The conventional participation aims “to provide citizens with checks of government power” [58] (p. 21) and is the only one among others not designed to empower citizens. Usually, these are meetings where the agenda is preset by the government side and where only issues from the agenda are allowed to be discussed. This may indicate poor process flexibility and susceptibility to manipulation. Contrary to conventional participation, thick participation means the ability to empower groups and can bring more effective problem solving. It “enables large numbers of people, working in small groups […], to learn, decide, and act. […] it is the most meaningful and powerful of three forms of direct participation” [58] (p. 14). Most common are participatory budgets, citizen assemblies, citizen juries, or study circles. The third form—thin participation—according to Nabathi and Leighninger enables a large group of citizens to express opinions, ideas, feelings, and doubts quickly. It can include different kinds of surveys, petitions, pools, fairs events, festivals, or online activities as social media.

Concluding the review of the issues concerning potential collaboration of citizens and local authorities, it bears noting that the literature touching on the subject rarely provides comprehensive solutions for PB in rural areas (some of the few indicated countries are Peru [59,60,61], top down process design and participation of vulnerable groups; Poland [62], coproduction of public services and PB system design; and Indonesia and Kenya [63], legal and finance issues). In most cases, this is caused by the lack of national regulations, whilst detailed areas of the analysis of participation mainly pertain to, in the case of China [64,65,66] for different areas of case studies, water supply, area planning, and waste management; in case of the UK [67], PB process design; for Russia [68], PB vs. public services delivery; for the Czech Republic [69], elderly and civic engagement; for Ukraine [70], problems with participation processes; for the Philippines [71], PB and poverty; for Italy [72], participation and smart villages; and worldwide [73,74], community participation in health care design and provision.

Based on the above, it would seem justifiable to state that the issue of public participation in managing the local matters may encompass a broad number of matters, which directly correlates with the substantial differences in the level of independence of particular communities and their competences.

2. State of Art—The Development of Rural Areas in Poland Through the Prism of PB

In Poland, the development of rural areas is viewed mainly through the prism of activities relating to the “Strategies for the balanced development of villages, farming, and fishing for years 2012–2020” from the year 2012 (as provisions of the act regulating the development policies [75], “Action Plan towards Responsible Development” from year 2016, as well as the mid-term country development strategy “Strategy for Responsible Development to year 2020 (with perspectives for year 2030)” from the year 2017 [76]. The first of the above-stated documents considers its main goal to be the “betterment of quality of life in rural areas and effective utilization of their resources and potential, including farming and fishing, in favour of the balanced development of the country”. This goal assumes the following:

- the improvement of the quality of social and human capital as well as increasing employment rates and supporting the growth of entrepreneurship in rural areas,

- the improvement of quality of life in rural areas and the spatial accessibility of terrain,

- food safety,

- the increase of productivity and competitiveness of the agri-food sector, and

- the protection of environment and the need to adapt to climate changes in rural areas.

Likewise, it is crucial to note that, in the frames of updating the above strategy, it was noted that actions would be undertaken as part of the activities relating to specific objective II—improvement of the quality of life, the infrastructure, and the state of environment. “The development of social infrastructure and revitalization of villages and small towns” has been designated as the direction this undertaking is to progress towards. Horizontal activities are to be considered in this scope relating to the modernized strategies ensuing from the “Strategy for Responsible Development” (pol. SOR–Strategia na rzecz Odpowiedzialnego Rozwoju), which (among others) concern better access of the citizens to basic public services, increasing the quality of local administration and stimulating the involvement of locals in building civic society as well as complementary activities for, among others, the betterment of the cooperation between the scientific community and the agricultural advisory in favour of social innovations in rural areas. It bears noting that these country strategic documents, to a limited degree, draw a connection between the development of rural areas and citizen participation. Nonetheless, it must be emphasized that, in recent years, Poland has seen a trend among the local governments in rural areas of steadily heading toward increasing their civic engagement in the decision-making process concerning public spending.

These municipalities constitute elementary units of administration division in Poland. An important fact of the matter is that the local government of such a community realizes the majority of local public tasks, which translates into a need of proper adjustment of the range, form, and scale of public goods available to citizens in accordance with their preferences. It also bears noting that the legislative and executive authorities of local territorial governments in Poland are meant to represent the respective local communities, which is to say, to ensure the realization of the concept of direct democracy. However, for the purpose of better adjusting public services to the needs of citizens, the legislator envisaged the possibility to hold consultations with the citizens [77,78] whose main forms are the participatory budget [48,79,80,81,82] and (only for rural areas) the Solecki fund [62,83,84]. The Solecki fund (pol. FS) as a form of participation of inhabitants was legally regulated in 2009 and subsequently modified in 2014. This fund constitutes a link between the formula of a participatory budget and the mechanism of complementing revenues of municipalities with low income base. The analysis of principles of functioning and effectiveness of this mechanism, however, must be preceded by a closer look at the general frames of functioning of the governing bodies eligible to utilize this formula.

There are three types of municipalities in place in Poland, based on the territorial scope: urban municipalities (town: 302), urban-rural municipality (urban and rural areas: 628), and rural municipalities (situated strictly in rural areas: 1548). The legislator also envisaged the possibility to establish supplementary units called “sołectwo” within the “rural areas” of municipalities (Table 3). These supplementary units are sometimes present in urban municipalities in Poland (11 in 2018), which often results from the agricultural nature of a given town (for example, following the expansion of its administrative borders); however, such municipalities have been omitted in the study due to their specific character. It ought to be noted that the number of municipalities using these supplementary units in the years 2010–2018 has not changed and that the shifts between the types of municipalities triggered by the municipalities were mostly caused by obtaining town rights by the villages acting as municipality headquarters. On the other hand, corrections were made as far as the number of solectwa is concerned; usually, new solectwa were extracted from the already existing ones for the purpose of adjusting the organizational structure of supplementary unit’s activities to the changes in settlement networks.

Table 3.

Municipalities in Poland: administrative structure.

Thus, a “sołectwo” is (with some minor exceptions) a nonmandatory supplementary unit of an urban-rural or rural commune, created for the purpose of completing a portion of the commune’s own tasks, which due to limitations in territorial range is specific for the said supplementary unit. A “sołectwo” usually territorially covers the area of one or several villages within the commune, whilst a municipality may have from a few up to several dozen of such supplementary units. In practice, this scale allows to match some of the undertakings realized by a municipality (as own tasks) to the specificity (citizen preferences) of a given “sołectwo”. According to article 1 par. 3 of the Solecki fund act [85], resources coming from the previously stated Solecki fund may be spent on the realization of projects indicated and chosen by the inhabitants of a sołectwo if all three of the following conditions are met:

- the submitted task must be the commune’s own task,

- it must serve for the benefit of improving the quality of life of the inhabitants, and

- it must be compatible with the developmental strategy of the commune.

Therefore, tasks realized by the Solecki fund clearly match the previously specified target 16.7 and 11.3 SDGs.

The commune’s own tasks which can be financed as part of the Solecki fund may include, among others, the following:

- organizing festivities, meetings, and corporate events;

- realizing promotional activities;

- tasks concerning the image and aesthetics of the village;

- tasks concerning the cultural and recreational infrastructure; and

- tasks concerning communal infrastructure.

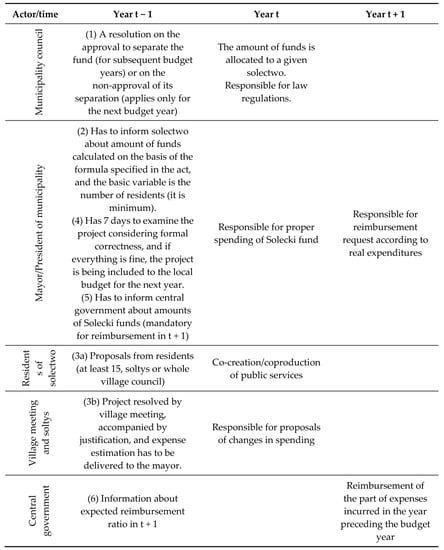

Establishing a Solecki fund is largely dependent on the decisions undertaken by the local authorities (village council—the legislative organ), as it is their responsibility to create supplementary units and to make decisions on whether such a fund is necessary. As can be understood from the procedure, the legislator assumed that, once a supplementary unit has been approved to be launched, it is functional until called off (Scheme 1). One can observe that, as part of the procedure of functioning of FS, many executive bodies will arise whose behaviour will determine the eventual reaching of the goals set by FS. One many note that (Scheme 1) this procedure is spread over the course of 3 years or is dependent on the timely and full completion of the tasks set out for each “actor”.

Scheme 1.

Simplified outline of the Solecki fund procedure.

As already mentioned, the starting point are the two decisions made by the legislative organ of a commune. During the same year (prior to the budget year), the executive organ of the municipality (vogt/mayor/president) determines the amounts for each solectwo and discloses the information regarding these funds to individual solectwa, which determines the scale of possible tasks to be undertaken in the framework of FS. Other important “actors” in the process are the citizens, the soltys and the Solecki council, all of whom have the ability to submit projects for realization as part of FS. The key role in the process of making a decision is played by the legislative organ of “sołectwo”, the village meeting (a gathering consisting of all the citizens of the sołectwo with the right to vote), during which decisions are undertaken and votes cast for individual projects. From the perspective of realization of incentives and redistribution of functions of FS, it bears noting that the information detailing the final planned expenditure under FS (following the verification of the project by the executive organ of the commune) is then passed on to the Ministry of Finance, where the degree of reimbursement of the expenses under the Solecki fund is calculated for each commune based on the collected data and the indicators of income per citizen. The realization of project tasks takes place during the following year under the supervision of the executive organ, which is simultaneously the trustee of the sołectwo resources on account of it not possessing legal personality. There is a possibility in place for a small correction of tasks; however, the authorities of a municipality cannot avoid the realization of the project tasks due to lacking funds. Reimbursement of partial funds comprising grants from the national budget in the year following the spending year may be viewed as the actual effect of realizing the expenses under the Solecki fund. The mechanism of reimbursement is designed to promote the inclusion of citizens in the decision-making process regarding local matters carried out by the local government of the commune.

The indicator of the minimal level of funds a solectwo may receive is on the one hand the appropriate base amount for a given commune, determined by the current income of the municipality and the number of its citizens (this is in accordance with the act; the quotient of the current expenses of the municipality in the year preceding the budget year by two years and the number of citizens living in the territory of the commune, as at December 31 of the year preceding the budget year by two years, as designated by the chairman of Statistics Poland (art. 3.1) [85]). On the other hand, the most essential factor in any given “sołectwo” is the number of citizens. The base amount of funds within the Solecki fund attributed to a “sołectwo” is regulated as not exceeding ten times the base amount; however, this limitation is for the purpose of calculating the reimbursement from the national budget, since municipalities may allocate higher amounts if it is deemed necessary for solectwa.

The general principle within the Act on Solecki Fund (Article 3 clause 7 and 8) [85] states that the municipality in which a Solecki fund was established and where expenses relating to the said fund were executed is entitled to a reimbursement of a part of the expenses sustained in the year preceding the budget year (Table 4). The relation between the base amount (KB) and the base amount calculated for all municipalities in the country (KBK) is what determines the returned amount. Municipalities where KB is lower than KBK are entitled to receive the greatest—40%—reimbursements of the expenses. On the other hand, municipalities where KB ranges from 100% to 120% of the average KBK may receive 30% and municipalities where KB is higher than 120% and not higher than 200% of the average KBK may receive 20%. It bears noting that the regulations also provide limitations on the funds directed to reimbursement of expenditure of Solecki Funds, which in practice forces the mechanism of reducing percentage thresholds.

Table 4.

Refund level from central government.

3. Materials and Methods

In this article, the authors opted for the analysis of application of the Solecki fund mechanism, which is one of the tools of support for the realization of SDGs in rural areas. Due (1) to the topicality of the raised issue in the context of the utilization of solutions in countries where the model of participation is implemented as an element of the strategies for balanced development, (2) to the stark contrast with similar models of participatory budged used in most other countries, (3) to its application in rural areas, as well as (4) to the limited scope of previous studies and low number of publications on the topic of Solecki Fund available in WoS and Scopus, the authors assumed that research would encompass the entire population of rural and urban-rural municipalities in Poland (around 2200 municipalities) in years 2010–2018 and, thus ultimately, the Solecki fund since its inception in Poland. The studies use reports provided by the Ministry of Finance for the years 2011–2019 concerning the budgets of municipalities in the years 2010–2018. The research procedure included the following:

- overview of publications indexed in WoS and Scopus concerning balanced development and the development of rural areas with particular attention to the role citizen participation plays in the moulding of public services offered to them by the local government (introduction);

- analysis of legal conditions which determine the functioning of citizen participation in Poland in rural areas (state-of-the-art);

- analysis of the dynamics of applying the Solecki fund in Poland during the studied period (in view of the optionality of this solution) on a country-wide and regional scale with a breakdown by municipality type (results and discussion). The reason for such a division is the differences observed in the prior analyses concerning the tendency of local governments and citizens to using this tool. Given the substantial disparities between each Solecki fund resulting from the method of calculating the limits, the analysis covered both the number of municipalities and the value of resources involved in Solecki funds; and

- analysis of the dynamics and scale of utilizing funds in the main areas of potential spendings, concerning national mechanisms and with a breakdown by regions and municipality types. This analysis serves to point out areas of activity for the improvement of the quality of life of citizens, and therefore realizing SDGs, the citizens of given municipalities/regions are viewed as essential. Also, in this part of the study, the analysis concerned the number of municipalities and the amount of involved funds.

Due to the formula which limits the level of reimbursement and to lack of data concerning transfers from the national budget to the budgets of municipalities, the authors did not analyse the scale of reimbursement of Solecki funds.

It bears noting that this analysis may constitute a worthwhile input to the discussion on the possibility and necessity of putting the solutions relating to participatory budget in legal frames.

4. Results and Discussion

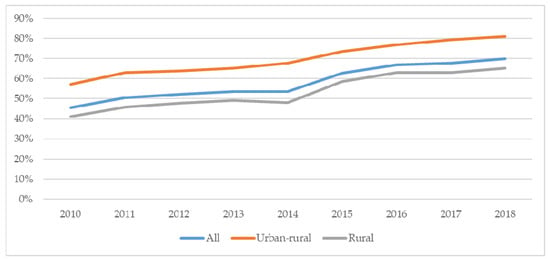

As it has been mentioned earlier, allocating funds for the implementation of tasks under the Solecki fund’s budget in the commune's budget is not obligatory, which causes the risk of lack of willingness to introduce such solutions by the municipality authorities. The analysis of the percentage of municipalities that took advantage of the possibility of introducing FS in the examined period indicates significant differences between urban-rural and rural municipalities (Figure 1). As can be observed, the percentage of urban-rural municipalities that made expenditures under the Solecki fund was significantly higher in the examined period (by about 15–20 pp), whilst due to the proportions in the number of rural and urban-rural municipalities, the average total percentage of municipalities from FS was on average by about 10 percentage points lower than in the case of urban-rural municipalities. Nevertheless, it should be emphasized that the 70% result in 2018 can be considered very good from the point of view of changes in the scale of FS application in the period considered.

Figure 1.

Municipalities with Solecki fund.

Following the increasing number of municipalities introducing the FS, the amount of funds allocated in this way by the municipalities increased. It should be noted that the value of funds engaged in the FS between 2010 and 2018 increased by over 300% (which is largely due to the calculation mechanism depending on the current income level of the municipality).

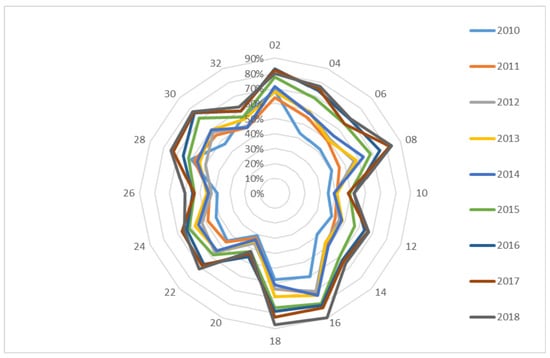

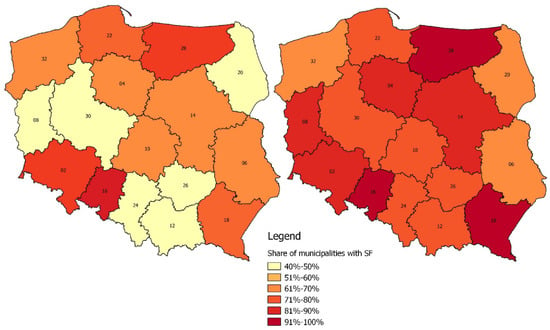

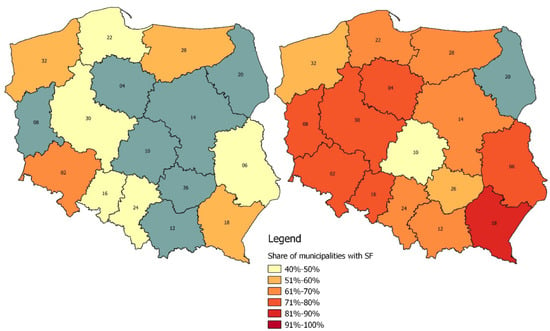

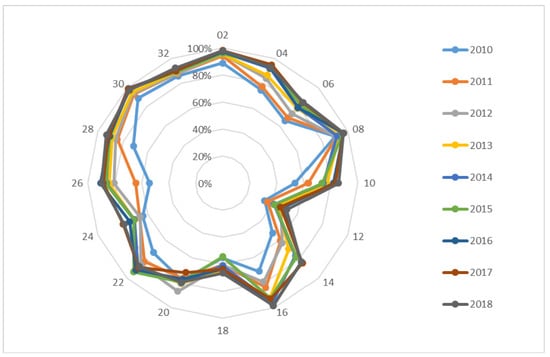

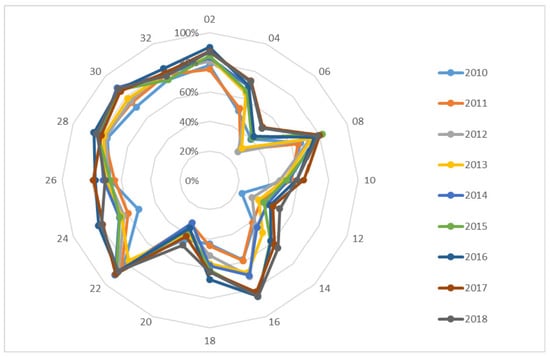

The analysis of territorial diversity in terms of the region (NUTS-2) indicates significant discrepancies in the scale of the use of Solecki funds in individual regions (Figure 2). In regions 2, 16, and 18, practically since the beginning of the period under review, there was a stronger tendency to use this form of participatory budget, while in Lubusz (8), this indicator was relatively low at the beginning of the period.

Figure 2.

Percentage of municipalities with the Solecki Fund (FS) in 2010–2018 in individual regions, where 02 is Lower Silesia, 04 is Kujawy-Pomerania, 06 is Lublin, 08 is Lubusz, 10 is Łódź, 12 is Lesser Poland, 14 is Mazovia, 16 is Opole, 18 is Podkarpackie, 20 is Podlasie, 22 is Pomerania, 24 is Silesia, 26 is Świętokrzyskie, 28 is Warmia-Masuria, 30 is Greater Poland, and 32 is West Pomerania.

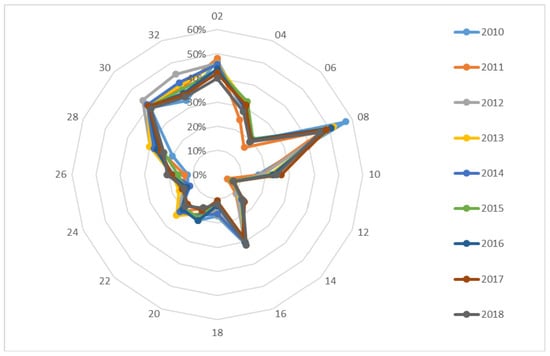

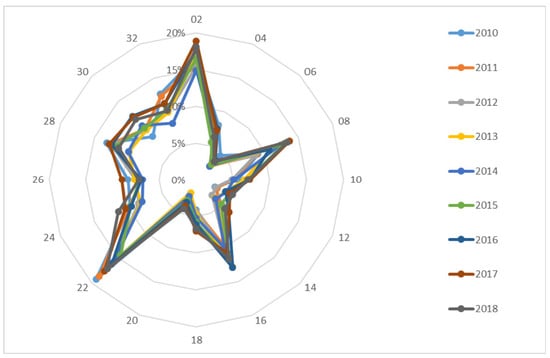

In turn, the analysis of the percentage of municipalities that used Solecki Fund, broken down into rural and urban-rural municipalities, provides additional information on the diversity of the scale of using the FS. Comparison of data from the beginning and the end of the research period indicates that, in the case of urban-rural municipalities (Figure 3), although there was a significant variation at the beginning of the period in the percentage of municipalities involved in FS processes, in the final period in most regions, a high percentage of municipalities using FS may be spotted. It should be remembered that, in some regions, the number of urban-rural municipalities is relatively small.

Figure 3.

Percentage of urban-rural municipalities with FS in 2010–2018 in individual regions.

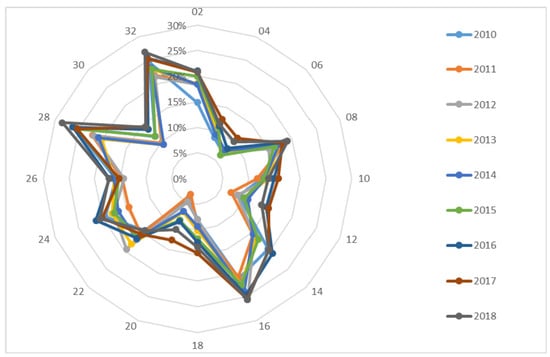

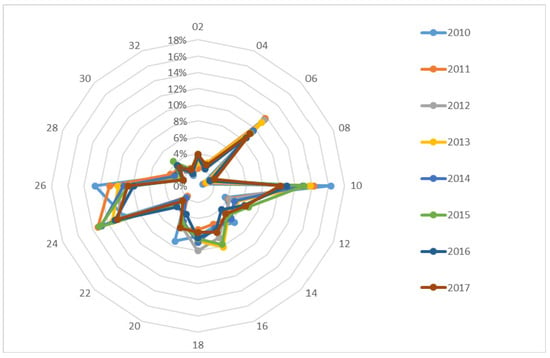

When analysing changes in the percentage of rural municipalities using Solecki funds, it ought to be noted in their case that these changes are not at all impressive. Figure 4 illustrates the scale of changes between 2010 and 2018, and it is worth noting that, in some regions, there were no significant changes, which may signify the occurrence of permanent factors affecting such behaviour of local authorities and citizens (lack of political will, low level of willingness to perform social activity, poor education in the field of social competences, lack of awareness of the existence of opportunities, etc.).

Figure 4.

Percentage of rural municipalities with the FS in 2010–2018 in individual regions.

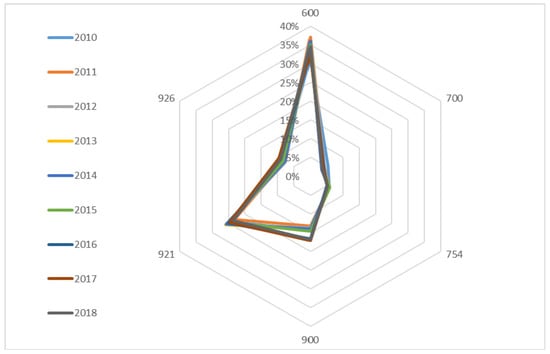

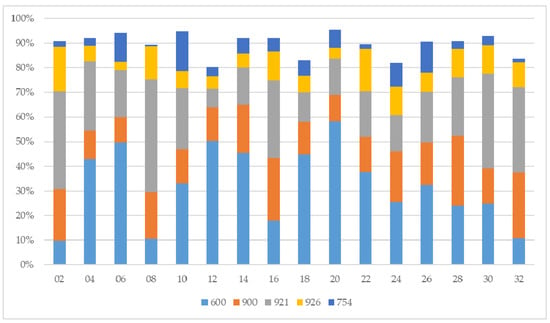

Taking as a criterion the scale and direction of disbursement of funds, it should be noted that, across the whole country, there are several disbursement (sections/divisions) areas (Figure 5). Due to the scale of disbursement, the area of expenditure in the field of transport and communications prevails, covering over 35% of total expenditure annually. Such a large amount of expenditure is also due to their specificity, associated with the high costs of individual ventures. However, there is a significant discrepancy in the share of this group of expenses in total expenditure from Solecki funds in regional dimension (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Share of the main expenditure directions under the FS in the total amount of expenditure, where (section/division) 600 is transport and communication, 921 is culture and protection of the national heritage, 900 is municipal services and environmental protection, 754 is public safety and fire protection, 926 is physical culture, and 700 is housing economy

Figure 6.

Percentage of the FS expenditure on transport and communication (600) in individual regions.

As it can be noticed from Figure 6 in individual regions, the share of expenditure from Solecki funds for transport and communications is definitely different. While in voivodships 02, 08, and 16, this share is extremely small, in voivodships 06, 12, 14, and 20, it exceeds 50% of the total expenditure from FS. While analysing the geographical location of these regions, it can be pointed out that, in the western voivodships of Poland, the discussed expenditure constituted the lowest percentage while, in the eastern voivodships, the largest share in the expenditure pool was observed.

The question about the number of local governments which included transport and communication expenses in the expenses under the Solecki funds remains unanswered. The regional analysis of the percentage of municipalities with expenditure in this area (Figure 7) clearly indicates that the differences between the regions do not result from the omission of transport and communication expenses implemented in the Solecki funds (the percentage of municipalities taking into account this type of expenditure varies between 70% and 100% in individual regions). The reasons for the existence of differences can be seen in the lower value of individual projects of this type in western regions, which may be due to better technical condition of the infrastructure, previously implemented investments, etc. and thus smaller needs in this respect reported by local communities for the FS projects.

Figure 7.

Percentage of municipalities with expenditure under FS for transport and communication (600).

From the point of view of the possibility of differences between urban-rural and rural municipalities in individual regions, it should be noted that the percentage of municipalities that include transport and communications expenses in the financial plans of Solecki funds fluctuates between 80% and 100% of municipalities in both rural and urban-rural municipalities with Solecki funds in individual regions, which clearly indicates the importance of this area of improving the quality of life for residents and, at the same time, confirms the thesis that it is mainly the differences in the scale of funding that affect such large disparities between regions.

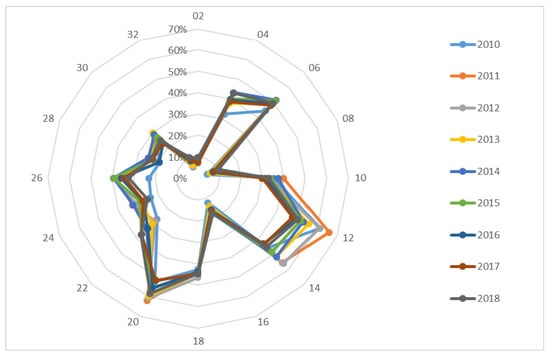

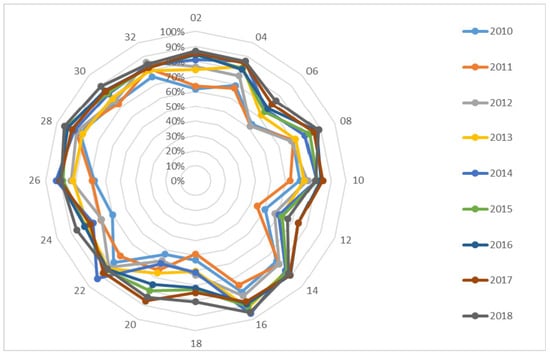

An analysis of the second largest disbursement of funds in the direction, culture and protection of national heritage, which annually absorbs about 25% of funds under the FS—indicates a significant differentiation in the percentage of total funds engaged by municipalities of individual regions in subsequent years and the persistence of these discrepancies throughout the entire studied period (Figure 8). In as many as 11 regions, the share of expenditure on culture and protection of national heritage usually fluctuated below 30% of total expenditure from the FS, while only in one (08), it oscillated within 50% of expenditure. When analysing the spatial distribution, it should be pointed out that the largest share of FS expenditure in the discussed area was recorded in the western Poland voivodships (02, 08, 16, 30, and 32). On the other hand, one cannot ignore the fact that, in most regions, the inhabitants of the vast majority of municipalities implementing expenditure from the FS included tasks in this field in the proposals to the FS (Figure 9). Only in the FS of municipalities of voivodships 12 and 18, one can observe much less occurrence of this type of expenditure in the entire analysed period. From the point of view of the differences in the significance of this direction of expenditure for the inhabitants of rural and urban-rural municipalities, it is visible that, only in voivodships 18, 20, and 24, there are significant differences between these two types of municipalities, with a significantly higher percentage of Solecki funds in municipal-rural voivodships 18 and 20 included expenditure on culture and protection of national heritage, and that, in voivodship 24, it occurred more often in rural municipalities.

Figure 8.

Percentage of expenses in section culture and protection of the national heritage (921).

Figure 9.

Percentage of municipalities with FS expenditure in section culture and protection of the national heritage (921).

Municipal services and environmental protection are yet another area of involvement of funds under Solecki funds. In the case of this direction of expenditure, one can also notice significant differences between individual regions in the scale of spending (Figure 10), with a similar level of interest of residents of this type of expenditure throughout the country (Figure 11). From the point of view of differences between rural and urban-rural municipalities, definitely a smaller percentage of rural municipalities (over 10%) in regions 06, 08, 12, 16, and 22 takes into account expenditure in this area within the Solecki funds. It can therefore be assumed that there are differences between regions in the scale of needs reported by residents and that the Solecki funds give the local community the opportunity to adjust the scale and direction of spending.

Figure 10.

Percentage of expenditure under the FS for section municipal services and environmental protection (900).

Figure 11.

Percentage of municipalities with FS expenditure in section municipal services and environmental protection (900).

The physical culture section is the fourth in the order of participation in the disbursed funds under FS. Considering the significance of this spending area for residents, we can see that, also in this group of spending, there are some differences between regions. In most of them, the percentage of expenditure on physical culture does not exceed 10% FS, usually oscillating around 5% (Figure 12). At the same time, it should be noted that, only in four voivodships, it significantly exceeded 10% of the expenditure (02, 08, 16, and 22) (Figure 13).

Figure 12.

Share of expenditure on physical culture section (926) in the FS in individual regions.

Figure 13.

Percentage of municipalities with FS expenditure in physical culture (926) section.

The last of the expenditure directions included in the analysis is public safety and fire protection. In the case of these expenditures from FS, we are dealing with a relatively small scale of their share in the expenditure of Solecki funds. It oscillates within 5% of the total expenditure; however, there are significant differences in the regional system. Municipalities of southeastern Poland (06, 10, 24, and 26) have a much higher share of expenditure under the FS for these tasks (Figure 14). At the same time, 60% to 80% of municipalities in all regions carried out tasks in this field under the FS (Figure 15). In addition, strong polarization is visible into regions in which much greater needs of residents in this area were reported in rural (02, 04, 12, 24, 28, and 32) and rural-urban (10, 18, and 22) municipalities.

Figure 14.

Share of expenditure on public safety and fire protection (754) in FS.

Figure 15.

Percentage of municipalities with expenditure on public safety and fire protection (754) in the FS.

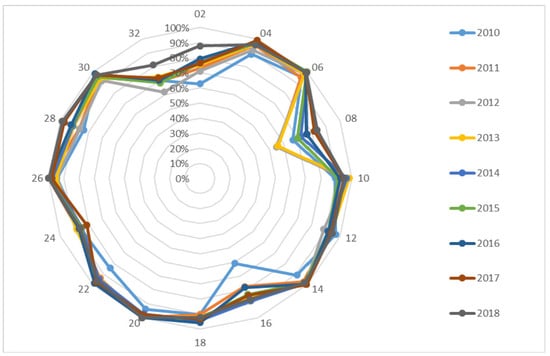

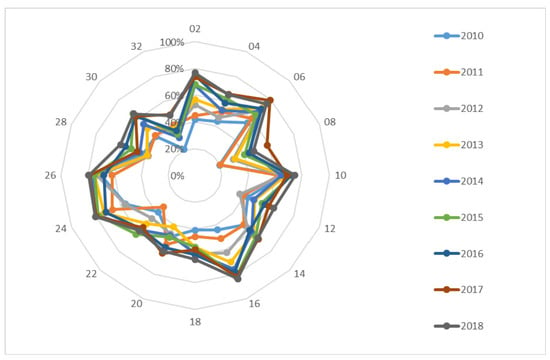

Based on the analysis of data from 2018 and on the previous detailed analysis of individual areas of spending the funds, it can be seen that (similarly to previous years) there were significant differences in the scale of funding commitment in the five main spending directions of the FS in individual regions. (Figure 16). It seems important that each region had its own specificity of the structure of FS expenditure, which speaks for the universality of the FS as a form of participatory budget. Of course, the aggregation of data at the level of regions is a generalization; however, it should be noted that previous analyses showed significant similarities in the scale and directions of spending funds under FS within individual voivodships.

Figure 16.

Engagement of funds in individual FS spending directions by region (2018).

The last element of the analysis stemming from an attempt to obtain a more complete picture of the allocation directions is an indication of the detailed spending directions which dominated the expenses within the FS, reported by residents. Therefore, in the area of transport and communications, the main streams of funds were allocated by residents to municipal roads (Table 5) since, according to the nominal approach, these expenses accounted for about 90% of transport and communications expenses every year. In the case of culture and protection of national heritage, the inhabitants chose primarily projects involving funds in the activities of cultural institutions: houses and cultural centres, club rooms, and clubs (between 60% and 70% of expenditure). It should be stated that expenses for “other activities” related primarily to the implementation of events and occasional meetings in the municipality have been gaining importance. On the other hand, in the case of municipal services and environmental protection, expenditure on actions aimed at improving the natural environment, at maintaining greenery in municipalities, and at improving safety through new investments in lighting of squares, streets, and bridges was perceived as a priority. In the area of public safety, residents chose tasks related to the support of volunteer fire brigades (purchase of equipment, means of transport, and renovation of facilities). In terms of physical culture, the choices of residents were varied; however, two main streams of resource allocation can be distinguished: construction and maintenance of sports facilities in the municipality and cofinancing of activities in the field of organizing sporting events in the commune.

Table 5.

Spending directions which dominated the expenses within the FS (%).

5. Conclusions

Detailed analysis of the functioning of the Solecki funds as one of the forms of participatory budget in Poland in rural areas conducted in the article indicates several important issues related to the adopted model of the functioning of the Solecki funds as a form of PB.

First of all, the article indicates that the adopted concept of legal empowerment of the Solecki fund institutions creates a clear framework for its functioning, which undoubtedly promotes the transparency of decisions on spending funds by the residents. At the same time, it guarantees a uniform legal framework for the participation of small local communities, characteristic of rural areas, in managing part of municipal expenditure.

Secondly, on the basis of the analysis, it can be concluded that, despite the existing legal regulations, the introduction of the Solecki fund undoubtedly depends on the political will of the local government's legislative authorities and on the willingness of residents to participate in decisions on spending directions. From the point of view of self-governance and independence of the commune, this solution should be assessed very positively because, despite the fact that we are dealing here with a regulation shaping the FS institution from above, the freedom to make decisions is left to the commune. This is undoubtedly an important indication for other countries of a solution satisfactory to local authorities with a kind of unification of the system of participatory budgets. This part of the article undoubtedly constitutes a substantial contribution to the discussion on the legitimacy of the use of national legal regulations when introducing a participatory budget.

Thirdly, the FS formula presented in the article has highlighted the possibility of using incentive mechanisms to introduce participatory budgets in the form of refinancing part of local government expenditure from the state budget, which can undoubtedly have an impact on the willingness of local authorities to entrust some decision-making competences to residents. It is therefore an indication of the possibility of indirect influence of national authorities on increasing the scale of PB processes at the local level.

Subsequently, the article demonstrates that the adopted formula of linking the scope of tasks that can be implemented from the participatory budget (here, the Solecki fund) with the catalogue of the commune's own tasks, and the reservation that, as a result of the task, the quality of life of the residents must improve has caused the implementation of tasks from the Solecki fund to fit into the concept of “SDG locality” in rural areas. It can therefore be concluded that the SF fits into the objectives (indicated in the introduction to the paper) target 16.7 of SDG 16 (ensure responsive, inclusive, participatory, and representative decision-making at all levels) and target 11.3 (sustainable human settlement planning and management) as the two most relevant in the context of PB use by LRGs.

Last but not least, the review of diversification of the scale and directions of expenditure of Solecki funds in the regional system with division into urban-rural and rural municipalities highlighted in the article the flexibility of the adopted solution and the possibility of adjusting it to the preferences of local communities in rural areas. Research results also clearly show the growing popularity of FS in rural areas.

Given the purpose of the article, which is to indicate the role of the FS in the implementation of SDGs by municipalities, it seems that the potential of the FS is not fully utilized. The current scale of funds foreseen for the expenses of the FS means that, if several projects are submitted under the “village meeting”, most of them may not be implemented. On the other hand, project proposals not considered should be presented to the commune council as information on the needs of residents and used when planning expenses from the municipality budget. It could be an additional function of the FS: informing about the significant needs of residents. Another issue is the practical limitation of FS spending on individual activities that may have little impact on improving their quality of life. The right direction seems to be a gradual increase in the scale of funds under the FS, enabling residents to influence the whole of tasks related to recreational areas: maintaining cleanliness, maintaining green areas, as well as investing in part of road and sewage and regulating road traffic. A severe barrier that may appear is the low level of citizen involvement of participation processes indicated in the part of the research devoted to FS, resulting, among others, from inadequate knowledge of FS procedures (need for education processes); the complexity of these procedures (need of simplification of the procedure); and frequent decision-making during one meeting at which projects are presented, discussed, and voted on. The solution to this problem could be introducing the obligation to have a several-stage project selection procedure, spread over time (submitting projects with discussion, discussion, and voting). The last issue is the problem of not being able to assess the impact of expenditure under the SF on improving the quality of life of residents. Information on the implementation of projects under the CFs available in the databases only pertains to the financial aspect, which translates into a high degree of generalization of the research conclusions.

The above studies also encountered significant limitations. It should be noted that, due to the very wide scope of municipalities in Poland and the large number of municipalities overal, the data have been aggregated to the size enabling them to be compared in the regional system and in relation to the most important categories of expenditure, which to some extent limits the possibilities of in-depth analysis. The research did not use advanced methods of statistical analysis because it was not intended to indicate the factors determining the use of FS institutions by municipalities (such studies can be found in the work of Olejniczak and Bednarska-Olejniczak [86], where the authors analysed the impact of the refinancing mechanism and the level of income of the municipality on the use of FS by it). Yet another important limitation in the analysis is the lack of qualitative research: interviews with local leaders and municipal authorities and which interviews would allow to assess the premises and barriers in making decisions about the introduction of Solecki funds and about the disadvantages of the discussed solution. Research in this area will be a continuation of the ongoing research project.

Despite these restrictions, the presented article clearly indicates the importance of Solecki funds as an instrument supporting the achievement of SGDs goals whilst filling the research gap regarding the functioning of participatory budgets in rural areas. The carried-out analysis undoubtedly constitutes a contribution to the discussion on solutions acceptable in various countries in the field of participatory budgets in rural areas as well as on the legitimacy of introducing top-down legal regulations regarding participatory budgets. The presented research results also constitute an empirical contribution to the research on the collective needs of rural residents.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.B.-O., J.O., and L.S.; formal analysis, J.O.; investigation, D.B.-O., J.O., and L.S.; methodology, D.B.-O., J.O., and L.S.; resources, D.B.-O. and J.O.; supervision, D.B.-O.; visualization, J.O.; writing—original draft, D.B.-O., J.O., and L.S.; writing—review and editing, J.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The project is financed by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education in Poland under the programme “Regional Initiative of Excellence” 2019–2022 project number 015/RID/2018/19 total funding amount 10 721 040,00 PLN.

Acknowledgments

This paper is a result of an International Scientific Cooperation Program (International Research Team) of Faculty of Economic Sciences, Wroclaw University of Economics, and it is a part of internal project Excellence 2020 at Faculty Informatics and Management, University of Hradec Kralove.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ellis, F.; Biggs, S. Evolving Themes in Rural Development 1950s–2000s. Dev. Policy Rev. 2001, 19, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Bank Rural Development (English). Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/688121468168853933/Rural-development-sector-policy-paper (accessed on 2 August 2019).

- Moseley, M.J. Rural Development: Principles and Practice; SAGE: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- European Union Cork 2.0 Declaration 2016. Available online: https://enrd.ec.europa.eu/sites/enrd/files/cork-declaration_en.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2019).

- Neumeier, S. Why do Social Innovations in Rural Development Matter and Should They be Considered More Seriously in Rural Development Research? Proposal for a Stronger Focus on Social Innovations in Rural Development Research. Sociol. Rural 2012, 52, 48–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulaert, F.; MacCallum, D.; Hillier, J. Social innovation: Intuition, precept, concept, theory and practice; Moulaert, F., MacCallum, D., Mehmood, A., Hamdouch, A., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd: Cheltenham, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Grimm, R.; Fox, C.; Baines, S.; Albertson, K. Social innovation, an answer to contemporary societal challenges? Locating the concept in theory and practice. Innov. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2013, 26, 436–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemec, J.; Mikusova Merickova, B.; Svidronova, M. Social Innovations in Public Services: Co-creation in Slovakia. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference: Current Trends in Public Sector Research, Šlapanice, Czech Republic, 22–23 January 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Novy, A.; Leubolt, B. Participatory Budgeting in Porto Alegre: Social Innovation and the Dialectical Relationship of State and Civil Society. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 2023–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdoch, J. Networks—A new paradigm of rural development? J. Rural Stud. 2000, 16, 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Ploeg, J.D.; Renting, H.; Brunori, G.; Knickel, K.; Mannion, J.; Marsden, T.; de Roest, K.; Sevilla-Guzman, E.; Ventura, F. Rural development: From practices and policies towards theory. Sociol. Rural 2000, 40, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shortall, S. Social or economic goals, civic inclusion or exclusion? An analysis of rural development theory and practice. Sociol. Rural 2004, 44, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meador, J.E.; Skerratt, S. On a unified theory of development: New institutional economics & the charismatic leader. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 53, 144–155. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, M. New directions in rural studies? J. Rural Stud. 2012, 28, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Pisani, J.A. Sustainable development—historical roots of the concept. Environ. Sci. 2006, 3, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockholm 1972—Declaration of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment—United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Available online: http://webarchive.loc.gov/all/20150314024203/http%3A//www.unep.org/Documents.Multilingual/Default.asp?documentid%3D97%26articleid%3D1503 (accessed on 15 August 2019).

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Griggs, D.; Stafford-Smith, M.; Gaffney, O.; Rockström, J.; Öhman, M.C.; Shyamsundar, P.; Steffen, W.; Glaser, G.; Kanie, N.; Noble, I. Sustainable development goals for people and planet: Policy. Nature 2013, 495, 305–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert, K.W.; Parris, T.M.; Leiserowitz, A.A. What is Sustainable Development? Goals, Indicators, Values, and Practice. Environ. Sci. Policy Sustain. Dev. 2005, 47, 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafford-Smith, M.; Griggs, D.; Gaffney, O.; Ullah, F.; Reyers, B.; Kanie, N.; Stigson, B.; Shrivastava, P.; Leach, M.; O’Connell, D. Integration: The key to implementing the Sustainable Development Goals. Sustain. Sci. 2017, 12, 911–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biermann, F.; Kanie, N.; Kim, R.E. Global governance by goal-setting: The novel approach of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2017, 26, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, E.; Linnerud, K.; Banister, D. Sustainable development: Our Common Future revisited. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 26, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franks, T.R. Managing Sustainable Development: Definitions, Paradigms, and Dimensions. Sustain. Dev. 1996, 4, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, E.B. The Concept of Sustainable Economic Development. Environ. Conserv. 1987, 14, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopwood, B.; Mellor, M.; O’Brien, G. Sustainable development: Mapping different approaches. Sustain. Dev. 2005, 13, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, P.P.; Jalal, K.F.; Boyd, J.A. An Introduction to Sustainable Development; Earthscan: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Emery, M.; Gutiérrez-Montes, I.; Fernández-Baca, E. Sustainable Rural Development: Sustainable Livelihoods and the Community Capitals Framework; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Per, B. Sustainability Science. In Managing Risk and Resilience for Sustainable Development; Becker, P., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Murdoch, J. Sustainable rural development: Towards a research agenda. Geoforum 1993, 24, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, E. Agriculture and the Environment: Perspectives on Sustainable Rural Development; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Akgun, A.A.; Baycan, T.; Nijkamp, P. Rethinking on Sustainable Rural Development. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2015, 23, 678–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisocka-Jaegermann, B. Sustainable Rural Development or (Sustainable) Rural Livelihoods? Strategies for the 21st Century in Peripheral Regions. Barom. Reg. Anal. Prognozy 2015, 1, 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Marsden, T.; Banks, J.; Renting, H.; Ploeg, J.D.V.D. The road towards sustainable rural development: Issues of theory, policy and research practice. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2001, 3, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez, A. Towards a Characterization of Sustainable Rural Development: A Systematic Review. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/333384812_Towards_a_Characterization_of_Sustainable_Rural_Development_A_Systematic_Review (accessed on 30 December 2019).

- Boggia, A.; Rocchi, L.; Paolotti, L.; Musotti, F.; Greco, S. Assessing Rural Sustainable Development potentialities using a Dominance-based Rough Set Approach. J. Environ. Manage. 2014, 144, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDP and UN Habitat. Roadmap for Localizing the SDGs: Implementation and Monitoring at Subnational Level—UN-Habitat; Global Taskforce of Local and Regional Governments, UNDP and UN Habitat: Barcelona, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sustainable Development through Local Action. Available online: https://www.local2030.org/library/705/Sustainable-Development-through-Local-Action.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2019).

- Local and Regional Governments Report. National and Sub-National Governments towards the Localization of the SDGs. Available online: http://www.uclg-decentralisation.org/es/node/1390 (accessed on 20 January 2020).

- 2nd Local and Regional Governments Report, Towards the Localization of the SDGs. Available online: https://www.global-taskforce.org/second-towards-localization-sdgs-report-2018-hlpf-presented-local-and-regional-governments-forum (accessed on 30 November 2019).

- 3rd Local and Regional Governments Report, Towards the Localization of the SDGs. Available online: https://www.uclg.org/en/media/news/3rd-local-and-regional-governments-report-towards-localization-sdgs-launched-2019-hlpf (accessed on 30 November 2019).

- Sriskandarajah, D. A People’s Agenda: Citizen Participation and the SDGs. In From Summits to Solutions, Innovations in Implementing the Sustainable Development Goals; Desai, R.M., Kato, H., Kharas, H., McArthur, J.W., Eds.; Brookings Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kanuri, C.; Revi, A.; Espey, J.; Kuhle, H. Getting Started with the SDGs in Cities. Available online: http://unsdsn.org/resources/publications/getting-started-with-the-sdgs-in-cities/ (accessed on 18 August 2019).

- Weymouth, R.; Hartz-Karp, J.; Weymouth, R.; Hartz-Karp, J. Principles for Integrating the Implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals in Cities. Urban Sci. 2018, 2, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, J.; Wheeler, J. What community development and citizen participation should contribute to the new global framework for sustainable development. Community Dev. J. 2015, 50, 552–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, Z.; Greyling, S.; Simon, D.; Arfvidsson, H.; Moodley, N.; Primo, N.; Wright, C. Local responses to global sustainability agendas: Learning from experimenting with the urban sustainable development goal in Cape Town. Sustain. Sci. 2017, 12, 785–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shand, W. Efficacy in Action: Mobilising Community Participation for Inclusive Urban Development. Urban Forum 2018, 29, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friant, M.C. Deliberating for sustainability: Lessons from the Porto Alegre experiment with participatory budgeting. Int. J. Urban Sustain. Dev. 2019, 11, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarska-Olejniczak, D.; Olejniczak, J.; Svobodova, L. Towards a Smart and Sustainable City with the Involvement of Public Participation-The Case of Wroclaw. Sustainability 2019, 11, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabannes, Y. Participatory Budgeting: A Powerful and Expanding Contribution to the Achievement of SDGs and Primarily SDG 16.7. Available online: https://participate.oidp.net/processes/SDGs/f/97/proposals/657 (accessed on 18 August 2019).

- Arnstein, S.R. A Ladder Of Citizen Participation. J. Am. Inst. Plann. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, D.M. A new ladder of citizen participation. Natl. Civ. Rev. 1988, 77, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langton, S.; Langton, S. What is citizen participation? In Citizen Participation in America: Essays on the State of the Art Edited by Stuart Langton; Lexington Books: Lexington, KY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Bednarska-Olejniczak, D. Public participation of Polish Millenials—problems of public communication and involvement in municipal affairs. In Proceedings of the 21st International Colloquium on Regional Sciences, Kurdejov, Czech Republic, 13–15 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, G.; Frewer, L.J. A Typology of Public Engagement Mechanisms. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 2005, 30, 251–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eversole, R. Knowledge Partnering for Community Development; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- IAP2 International Association for Public Participation (IAP2). Available online: https://www.iap2.org/page/resources (accessed on 15 November 2018).

- AbouAssi, K.; Nabatchi, T.; Antoun, R. Citizen Participation in Public Administration: Views from Lebanon. Int. J. Public Adm. 2013, 36, 1029–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabatchi, T.; Leighninger, M. Public Participation for 21st Century Democracy; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- McNulty, S.L. Participatory Decentralization Reform, Peru. In Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance; Farazmand, A., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 1–8. ISBN 978-3-319-31816-5. [Google Scholar]

- McNulty, S.L. Barriers to Participation: Exploring Gender in Peru’s Participatory Budget Process. J. Dev. Stud. 2015, 51, 1429–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, M.; Wright, G.D. Participatory Democracy and Effective Policy: Is There a Link? Evidence from Rural Peru. World Dev. 2015, 66, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olejniczak, J.; Bednarska-Olejniczak, D. Co-Production of Public Services in Rural Areas—the Polish Way. In Proceedings of the XXII. Mezinárodní Kolokvium o Regionálních Vědách, Velke Bilovice, Czech Republic, 12–14 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wampler, B.; Touchton, M. Participatory budgeting: Adoption and transformation. In Making All Voices Count Research Briefing; IDS: Brighton, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, M. Participatory budgeting, rural public services and pilot local democracy reform. Field Actions Sci. Rep. 2014, 11, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Cabannes, Y.; Ming, Z. Participatory budgeting at scale and bridging the rural−urban divide in Chengdu. Environ. Urban. 2014, 26, 257–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Fan, P.; Liu, Y. What makes better village development in traditional agricultural areas of China? Evidence from long-term observation of typical villages. Habitat Int. 2019, 83, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moir, E.; Leyshon, M. The design of decision-making: Participatory budgeting and the production of localism. Local Environ. 2013, 18, 1002–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beuermann, D.W.; Amelina, M. Does participatory budgeting improve decentralized public service delivery? Experimental evidence from rural Russia. Econ. Gov. 2018, 19, 339–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafkova, M.P.; Vidovicova, L.; Wija, P. Older Adults and Civic Engagement in Rural Areas of the Czech Republic. Eur. Ctry. 2018, 10, 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvartiuk, V.; Curtiss, J. Participatory rural development without participation: Insights from Ukraine. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 69, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saguin, K. Why the poor do not benefit from community-driven development: Lessons from participatory budgeting. World Dev. 2018, 112, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soligno, R.; Scorza, F.; Amato, F.; Casas, G.L.; Murgante, B. Citizens Participation in Improving Rural Communities Quality of Life. In Proceedings of the Computational Science and Its Applications—ICCSA 2015, Banff, AB, Canada, 22–25 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, M.; Escobar, O.; Fenton, C.; Craig, P. The impact of participatory budgeting on health and wellbeing: A scoping review of evaluations. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, A.; Farmer, J.; Dickson-Swift, V.; Hyett, N. Community participation for rural health: A review of challenges. Health Expect. Int. J. Public Particip. Health Care Health Policy 2015, 18, 1906–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Act of 6 December 2006 on Regulating the Development Policies 2006. Available online: http://prawo.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20062271658 (accessed on 20 December 2019).

- Resolution No. 8 of the Council of Ministers of February 14, 2017 on Adopting the Strategy for Responsible Development until 2020. Available online: http://prawo.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WMP20170000260 (accessed on 26 June 2019).

- Bednarska-Olejniczak, D.; Olejniczak, J. Participatory budget of Wrocław as an element of smart city 3.0 concept. In Proceedings of the 19th International Colloquium on Regional Sciences, Brno, Czech Republic, 15–17 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bednarska-Olejniczak, D.; Olejniczak, J. Participatory Budgeting in Poland—Finance And Marketing Selected Issues. In Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference Hradec Economic Days 2017, Hradec Králové, Czech Republic, 31 January–1 February 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bednarska-Olejniczak, D.; Olejniczak, J. Participatory Budgeting in Poland in 2013–2018—Six Years of Experiences and Directions of Changes. In Hope for Democracy. 30 Years of Participatory Budgeting Worldwide; Dias, N., Ed.; Epopeia Records & Oficina: Faro, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Poniatowicz, M. Kontrowersje wokół idei budżetu partycypacyjnego jako instrumentu finansów lokalnych. Stud. Ekon. 2014, 198, 177–188. [Google Scholar]

- Kamrowska-Zaluska, D. Participatory Budgeting in Poland – Missing Link in Urban Regeneration Process. Procedia Eng. 2016, 161, 1996–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sześciło, D. Participatory Budgeting in Poland: Quasi-Referendum Instead of Deliberation. Croat. Comp. Public Adm. 2015, 15, 373–388. [Google Scholar]

- Sześciło, D.; Wilk, B. Can Top Down Participatory Budgeting Work? The Case of Polish Community Fund. Cent. Eur. Public Adm. Rev. 2018, 16, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feltynowski, M.; Rzeńca, A. Solecki Fund as Instrument in the Hands of Rural Development Policy Makers. In Infrastructure and Environment; Krakowiak-Bal, A., Vaverkova, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Act of 21 February 2014 on Solecki Fund 2014. Available online: http://prawo.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20140000301 (accessed on 10 November 2019).