Adapting Collaborative Approaches for Service Provision to Low-Income Countries: Expert Panel Results

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Gaps

1.1.1. Literature Lacks Evidence of Collaborative Approaches in Low-income Countries

1.1.2. Literature Remains Largely Disconnected and Lacks Standard Terminology

1.2. Point of Departure and Research Question

2. Research Approach and Methods

2.1. Compiling a List of Factors

2.2. Delphi Expert Panel

2.2.1. Measuring Consensus

2.2.2. Controls Against Bias

2.2.3. Validity of Results

3. Results

3.1. Contextual Conditions

“When faced with highly unstable circumstances, many actors revert to coordinating activities instead of more integrated collaboration. If a coalition is built during a time of greater stability, then those actors deeply engaged in a coalition can respond better to moments of crisis or instability when they arise. Expecting to build high levels of trust and collaboration in the midst of a crisis without having previous collaboration among actors presents more challenges than if there is a history of engagement”.

“The instability may impact the ability to concretely plan for and achieve intended outcomes, but [it] is critical for partners to work together on common challenges in an unstable context… By coming together to tackle common challenges, the coalition may have opportunity to impact the stability of [the] enabling environment. It may be necessary to explore different models for collaboration in stable versus unstable contexts… for better development outcomes”.

3.2. Design Components

3.3. Intermediate Results

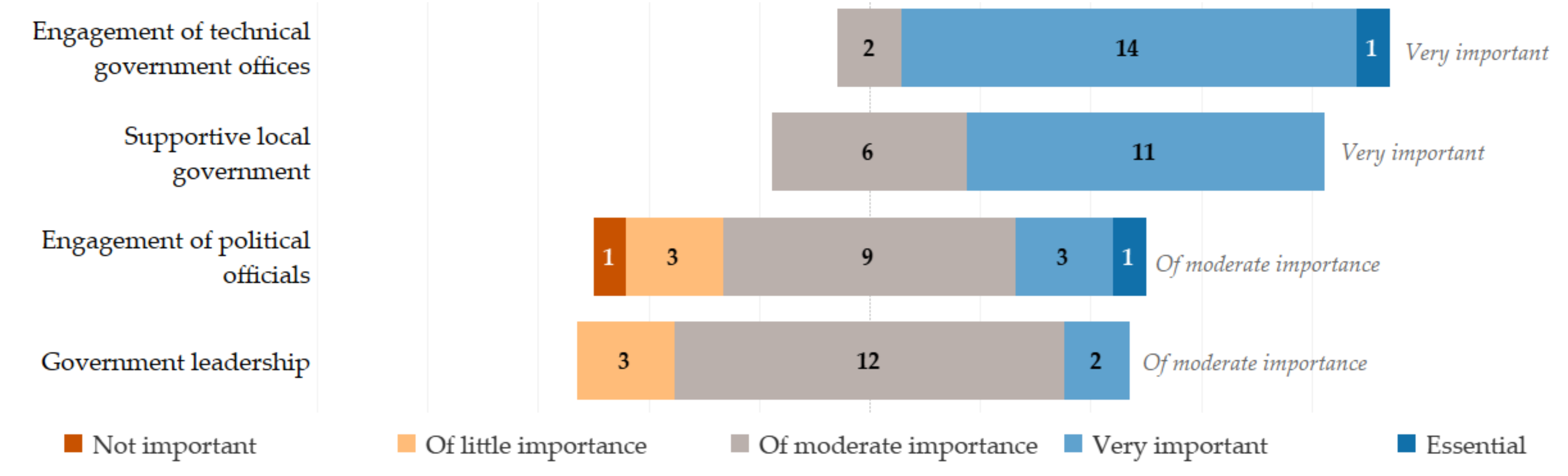

3.4. Special Focus: Government Engagement

“It’s important to look beyond the political, to the technical and strategic development aspects of government. Building this type of engagement or engaging at [these] levels provides [a] structural basis to anchor approaches and efforts. As such the local government support is very important, particularly, where strategically engaged to achieve common/tandem objectives and goals, that align with development or strategic plans”.

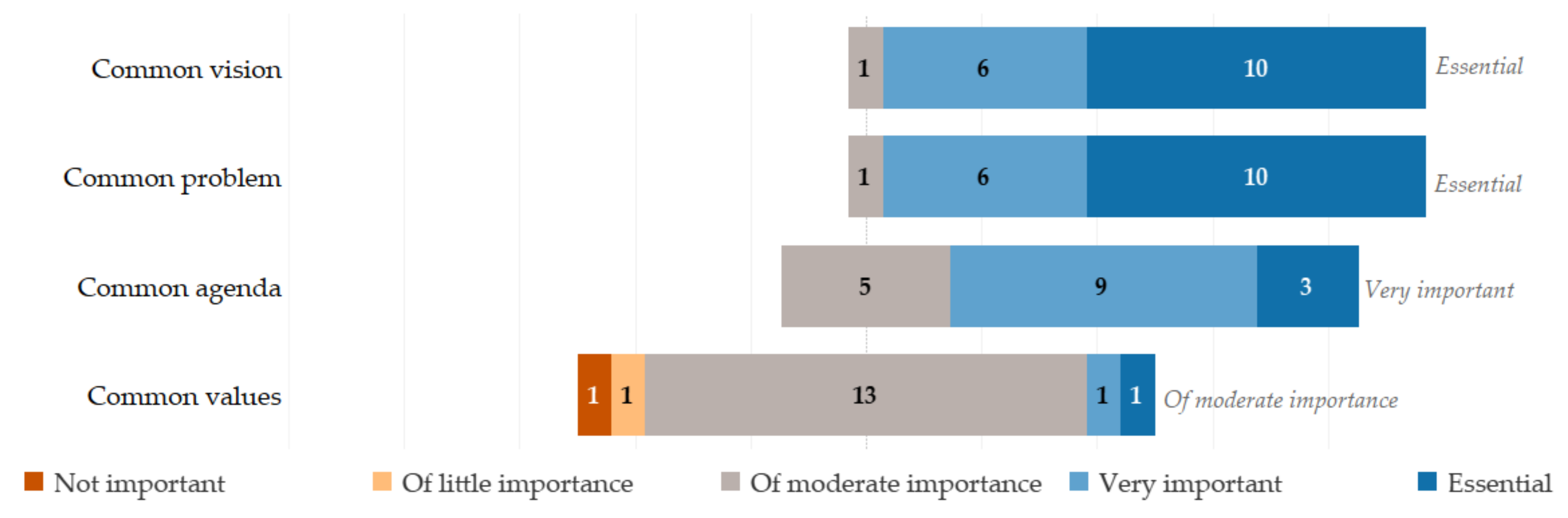

3.5. Special Focus: Common Orientation Around an Issue

4. Discussion

4.1. Differences in Low-Income Country Contexts

“Instability provides a greater impetus for collaboration as different strengths, skills and perspectives are brought to bear on a common problem/challenge. The instability may impact the ability to concretely plan for and achieve intended outcomes, but is critical for partners to work together on common challenges in an unstable context. It may be necessary to explore different models for collaboration in stable versus unstable contexts, to explore capacity for better development outcomes”.

“Culturally, is this a patriarchy where centralized decision making makes sense and feels ’normal’ for the constituents? Is there so much turbulence that the locals would much prefer some clear accountability through quasi-bureaucratic structures that come with centralized decision making? Alternately, is this a collective society where participation is the norm?”

4.2. Differences in Service Delivery Applications

4.3. Differences in Intensity of Desired Collaboration

“When faced with highly unstable circumstances, many actors revert to coordinating activities instead of more integrated collaboration. If a coalition is built during a time of greater stability, then those actors deeply engaged in a coalition can respond better to moments of crisis or instability when they arise. Expecting to build high levels of trust and collaboration in the midst of a crisis without having previous collaboration among actors presents more challenges than if there is a history of engagement”.

4.4. Future Work

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Summary of Considerations for Future Practice and Research

| Summary of Considerations for Future Practice | Summary of Considerations for Future Research |

|---|---|

Planning

| Topics to investigate

|

References

- Kushner, D.C.; MacLean, L.M. Introduction to the Special Issue: The Politics of the Nonstate Provision of Public Goods in Africa. Afr. Today 2015, 62, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katusiimeh, M.W. The Nonstate Provision of Health Services and Citizen Accountability in Uganda. Afr. Today 2015, 62, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyessi, A.G. Community-based urban water management in fringe neighbourhoods: The case of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Habitat Int. 2005, 29, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darteh, B.; Moriarty, P.; Huston, A. How to Use Learning Alliances to Achieve Systems Change at Scale; IRC: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2019; p. 31. [Google Scholar]

- USAID. Local Systems: A Framework for Supporting Sustained Development; USAID: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; p. 23. [Google Scholar]

- USAID. Self Reliance Learning Agenda Fact Sheet: Evidence to Support the Journey to Self Reliance. 2019. Available online: https://www.usaid.gov/documents/1870/self-reliance-learning-agenda-fact-sheet (accessed on 16 September 2019).

- Kaufmann, D.; Kraay, A. Worldwide Governance Indicators; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mo Ibrahim Foundation. African Governance Report: Agendas 2063 & 2030: Is Africa on Track? Mo Ibrahim Foundation: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann, D.; Kraay, A.; Mastruzzi, M. The Worldwide Governance Indicators: Methodology and Analytical Issues. Hague J. Rule Law 2011, 3, 220–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kania, J.; Kramer, M.; Collective Impact. In Stanford Social Innovation Review; 2011; Winter, pp. 36–41. Available online: https://senate.humboldt.edu/sites/default/files/senate/Chair%20Written%20Report%201-23-2018.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2020).

- Tetra Tech. AguaConsult Beyond Collaboration: Learning from National and District-level Collective Action Efforts in WASH; IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 58–59. [Google Scholar]

- Kekez, A.; Howlett, M.; Ramesh, M. Collaboration in public service delivery: What, when and how. In Collaboration in Public Service Delivery; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; pp. 2–19. ISBN 978-1-78897-858-3. [Google Scholar]

- Heath, R.G.; Isbell, M.G. Interorganizational Collaboration: Complexity, Ethics, and Communication; Waveland Press Inc.: Long Groce, IL, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-4786-3293-1. [Google Scholar]

- Koschmann, M.A.; Sanders, M. Understanding Nonprofit Work: A Communication Perspective; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-1-119-43125-1. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, B.; Purdy, J. Collaborating for Our Future: Multistakeholder Partnerships for Solving Complex Problems; Oxford Scholarship Online: Oxford, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-0-19-878284-1. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, B. Collaborating: Finding Common Ground for Multiparty Problems, 1st ed.; Jossey-Bass Management Series; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1989; ISBN 978-1-55542-159-5. [Google Scholar]

- Koschmann, M.A. The Communicative Accomplishment of Collaboration Failure: Collaboration Failure. J. Commun. 2016, 66, 409–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative Governance in Theory and Practice. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2007, 18, 543–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, K.; Nabatchi, T.; Balogh, S. An Integrative Framework for Collaborative Governance. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2012, 22, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huxham, C. Theorizing collaboration practice. Public Manag. Rev. 2003, 5, 401–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, L.K. Collaborative interaction: Review of communication scholarship and a research agenda. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 2006, 30, 197–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu, F.; Ohemeng, F.L.K. The Public Sector and Development in Africa: The Case for a Developmental Public Service. In Rethinking Development Challenges for Public Policy: Insights from Contemporary Africa; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2012; pp. 117–154. [Google Scholar]

- Larbi, G.A. Institutional constraints and capacity issues in decentralizing management in public services: The case of health in Ghana. J. Int. Dev. 1998, 10, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, A.E.; Bronsoler, V.; Salman, L. Hybrid Regimes for Local Public Goods Provision: A Framework for Analysis. Perspect. Polit. 2017, 15, 952–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Motivation, leadership, and organization: Do American theories apply abroad? Organ. Dyn. 1980, 9, 42–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra, H. National Cultures and Work-Related Values: The Hofstede Study; Harvard Business School: Boston, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ayee, J.R.A. Improving Effectiveness of Africa’s Public Sector. In Rethinking Development Challenges for Public Policy: Insights from Contemporary Africa; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2012; pp. 83–116. [Google Scholar]

- Mxakato-Diseko, N.J. The Changing Role and Image of the Public Service in Africa. Presented at the Workshop for Enhancing the Performance of the African Public Service Commissions and Other Appointing Commissions/Authorities, Kampala, Uganda, 7–11 April 2008; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Estrin, S.; Pelletier, A. Privatization in Developing Countries: What Are the Lessons of Recent Experience? World Bank Res. Obs. 2018, 33, 65–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF; WHO. Progress on Household Drinking Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene 2000—2017; Special Focus on Inequalities: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- RWSN. Myths of the Rural Water Supply Sector. RWSN Perspectives; RWSN: Gallen, Switzerland, 2010; p. 7. Available online: https://www.rural-water-supply.net/en/resources/details/226 (accessed on 9 March 2019).

- Brinkerhoff, D.W.; Brinkerhoff, J.M. Public Sector Management Reform in Developing Countries: Perspectives Beyond NPM Orthodoxy: Public Sector Management Reform. Public Adm. Dev. 2015, 35, 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriarty, P.; Smits, S.; Butterworth, J.; Franceys, R. Trends in Rural Water Supply: Towards a Service Delivery Approach. Water Altern. 2013, 6, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Bayliss, K. Utility privatisation in Sub-Saharan Africa: A case study of water. J. Mod. Afr. Stud. 2003, 41, 507–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acey, C. Hybrid Governance and the Human Right to Water. Plan. J. 2016, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajenthira, A.; Sion, P. Collective Impact without Borders. Available online: https://ssir.org/articles/entry/collective_impact_without_borders (accessed on 9 January 2019).

- Christens, B.D.; Inzeo, P.T. Widening the view: Situating collective impact among frameworks for community-led change. Commun. Dev. 2015, 46, 420–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanleybrown, F.; Kania, J.; Kramer, M. Channeling Change: Making Collective Impact Work. 2012. Available online: https://ssir.org/articles/entry/channeling_change_making_collective_impact_work (accessed on 10 April 2018).

- Talesh, S. Public law and regulatory theory. In Handbook on Theories of Governance; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2016; pp. 102–110. ISBN 978-1-78254-849-2. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, B. Assessing inter-organizational collaboration: Multiple conceptions and multiple methods. In Cooperative strategy: Economic, business, and organizational issues; Oxford University Press Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 243–260. ISBN 0-19-829689-4. [Google Scholar]

- Keyton, J.; Ford, D.J.; Smith, F.L. A Mesolevel Communicative Model of Collaboration. Commun. Theory 2008, 18, 376–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoon, M.; Cox, M. Collaboration, Adaptation, and Scaling: Perspectives on Environmental Governance for Sustainability. Sustainability 2018, 10, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrelja, R.; Pettersson, F.; Westerdahl, S. The Qualities Needed for a Successful Collaboration: A Contribution to the Conceptual Understanding of Collaboration for Efficient Public Transport. Sustainability 2016, 8, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feiock, R.C. The Institutional Collective Action Framework: Institutional Collective Action Framework. Policy Stud. J. 2013, 41, 397–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margerum, R. Beyond Consensus; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lasker, R.D.; Weiss, E.S.; Miller, R. Partnership Synergy: A Practical Framework for Studying and Strengthening the Collaborative Advantage. Milbank Q. 2001, 79, 179–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolff, T. A Practitioner’s Guide to Successful Coalitions. Am. J. Commun. Psychol. 2001, 29, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, M.; Stewart, R.; Fielding, K.; Cochrane, J.; Beal, C. Collaborating for Sustainable Water and Energy Management: Assessment and Categorisation of Indigenous Involvement in Remote Australian Communities. Sustainability 2019, 11, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala-Orozco, B.; Rosell, J.; Merçon, J.; Bueno, I.; Alatorre-Frenk, G.; Langle-Flores, A.; Lobato, A. Challenges and Strategies in Place-Based Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration for Sustainability: Learning from Experiences in the Global South. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, J. Multi-Stakeholder Platforms for Integrated Water Management; Routledge: New York, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, S.; Hayes, J.P.; Stibbe, D. Platforms for Partnership: Emerging Good Practice to Systematically Engage Business as a Partner in Development; The Partnering Initiative: Oxford, UK, 2014; Available online: https://www.thepartneringinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/PLATFORMStealcoverallpages.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2020).

- Verhallen, A.; Warner, J.; Santbergen, L. Towards Evaluating MSPs for Integrated Catchment Management. In Multi-Stakeholder Platforms for Integrated Water Management; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 259–271. [Google Scholar]

- Torgersen, G.-E. Interaction: “Samhandling” under Risk—A Step Ahead of the Unforeseen. Cappelen Damm Akademisk/NOASP: Oslo, Norway, 2018; ISBN 978-82-02-53502-5. [Google Scholar]

- Mayan, M.; Pauchulo, A.L.; Gillespie, D.; Misita, D.; Mejia, T. The promise of collective impact partnerships. Commun. Dev. J. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabaj, M.; Weaver, L. Collective Impact 3.0. In Using Collective Impact to Bring Community Change; Series: The Community Development Research and Practice Series; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Volume 9, pp. 97–112. ISBN 978-1-315-54507-3. [Google Scholar]

- Blatz, J. Filling the Gaps in Collective Impact. Stanf. Soc. Innov. Rev. 2019, 5. Available online: https://ssir.org/articles/entry/filling_the_gaps_in_collective_impact?utm_source=newsletter&utm_medium=email&utm_content=Article%3A%20Filling%20the%20Gaps%20in%20Collective%20Impact&utm_campaign=CIF2019VCKeyFactorsInvite# (accessed on 26 November 2019).

- Flood, J.; Minkler, M.; Hennessey Lavery, S.; Estrada, J.; Falbe, J. The Collective Impact Model and Its Potential for Health Promotion: Overview and Case Study of a Healthy Retail Initiative in San Francisco. Health Educ. Behav. 2015, 42, 654–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walzer, N.; Weaver, L.; McGuire, C. Collective impact approaches and community development issues. Commun. Dev. 2016, 47, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The CEO Water Mandate. Guide to Water-Related Collective Action; UN Global Compact: New York, NY, USA, 2013; p. 56. [Google Scholar]

- Dalkey, N.; Helmer, O. An Experimental Application of the DELPHI Method to the Use of Experts. Manag. Sci. 1963, 9, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perveen, S.; Kamruzzaman, M.D.; Yigitcanlar, T. Developing Policy Scenarios for Sustainable Urban Growth Management: A Delphi Approach. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henning, J.; Jordaan, H. Determinants of Financial Sustainability for Farm Credit Applications—A Delphi Study. Sustainability 2016, 8, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, E.; Javernick-Will, A. Indicators of Community Recovery: Content Analysis and Delphi Approach. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2013, 14, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallowell, M.R.; Gambatese, J.A. Qualitative Research: Application of the Delphi Method to CEM Research. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2010, 136, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, B.; Wood, D.J. Collaborative alliances: Moving from practice to theory. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 1991, 27, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative Platforms as a Governance Strategy. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2018, 28, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, K.; Nabatchi, T. Collaborative Governance Regimes; Public Management and Change Series; Georgetown University Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-62616-252-5. [Google Scholar]

- Dedoose. 2.14 Web Application for Managing Analyzing and Presenting Qualitative and Mixed Method Research Data; Version 8; SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Blackstone, A. Chapter 11: Unobtrusive Research. In Principles of Sociological Inquiry—Qualitative and Quantitative Methods; Saylor Foundation: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-1-4533-2889-7. [Google Scholar]

- Nkum Associates. Research on Learning Alliance Approach; Triple S Project Report; IRC Ghana: Accra, Ghana, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Smits, S.; Moriarty, P. Learning Alliances: Scaling Up Innovations in Water, Sanitation and Hygiene; IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre: Delft, The Netherlands, 2007; ISBN 978-90-6687-056-7. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, R.C. Managing Delphi Surveys Using Nonparametric Statistical Techniques. Decis. Sci. 1997, 28, 763–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von der Gracht, H.A. Consensus measurement in Delphi studies. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2012, 79, 1525–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, C.D.; Basinski, A.; Baigrie, R.S.; Goldman, B.S.; Lomas, J. Placing patients in the queue for coronary revascularization: Evidence for practice variations from an expert panel process. Am. J. Public Health 1990, 80, 1246–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cafiso, S.; Di Graziano, A.; Pappalardo, G. Using the Delphi method to evaluate opinions of public transport managers on bus safety. Saf. Sci. 2013, 57, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillam, R.J.; Counts, J.M.; Garstka, T.A. Collective impact facilitators: How contextual and procedural factors influence collaboration. Commun. Dev. 2016, 47, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulibarri, N. Tracing Process to Performance of Collaborative Governance: A Comparative Case Study of Federal Hydropower Licensing: Ulibarri: A Comparative Case Study of Federal Hydropower Licensing. Policy Stud. J. 2015, 43, 283–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofoegbu, C.; New, M.; Staline, K. The Effect of Inter-Organisational Collaboration Networks on Climate Knowledge Flows and Communication to Pastoralists in Kenya. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Contextual Conditions | Design Components | Intermediate Results | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| Measure of Dispersion | Equation, for a Set of Scores [X1, X2, X3, … Xn] | Threshold Value for Consensus |

|---|---|---|

| Median absolute deviation | median (| Xi – median(X1→ n )|) | 0 |

| Mean absolute deviation | mean (| Xi – mean(X1→ n )|) | < 0.6 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pugel, K.; Javernick-Will, A.; Koschmann, M.; Peabody, S.; Linden, K. Adapting Collaborative Approaches for Service Provision to Low-Income Countries: Expert Panel Results. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2612. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072612

Pugel K, Javernick-Will A, Koschmann M, Peabody S, Linden K. Adapting Collaborative Approaches for Service Provision to Low-Income Countries: Expert Panel Results. Sustainability. 2020; 12(7):2612. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072612

Chicago/Turabian StylePugel, Kimberly, Amy Javernick-Will, Matthew Koschmann, Shawn Peabody, and Karl Linden. 2020. "Adapting Collaborative Approaches for Service Provision to Low-Income Countries: Expert Panel Results" Sustainability 12, no. 7: 2612. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072612

APA StylePugel, K., Javernick-Will, A., Koschmann, M., Peabody, S., & Linden, K. (2020). Adapting Collaborative Approaches for Service Provision to Low-Income Countries: Expert Panel Results. Sustainability, 12(7), 2612. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072612