A Collaborative Transformation beyond Coal and Cars? Co-Creation and Corporatism in the German Energy and Mobility Transitions

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Unpacking the Notion of Collaborative Transformation

1.2. Collaboration as an Institution in German Policy-Making

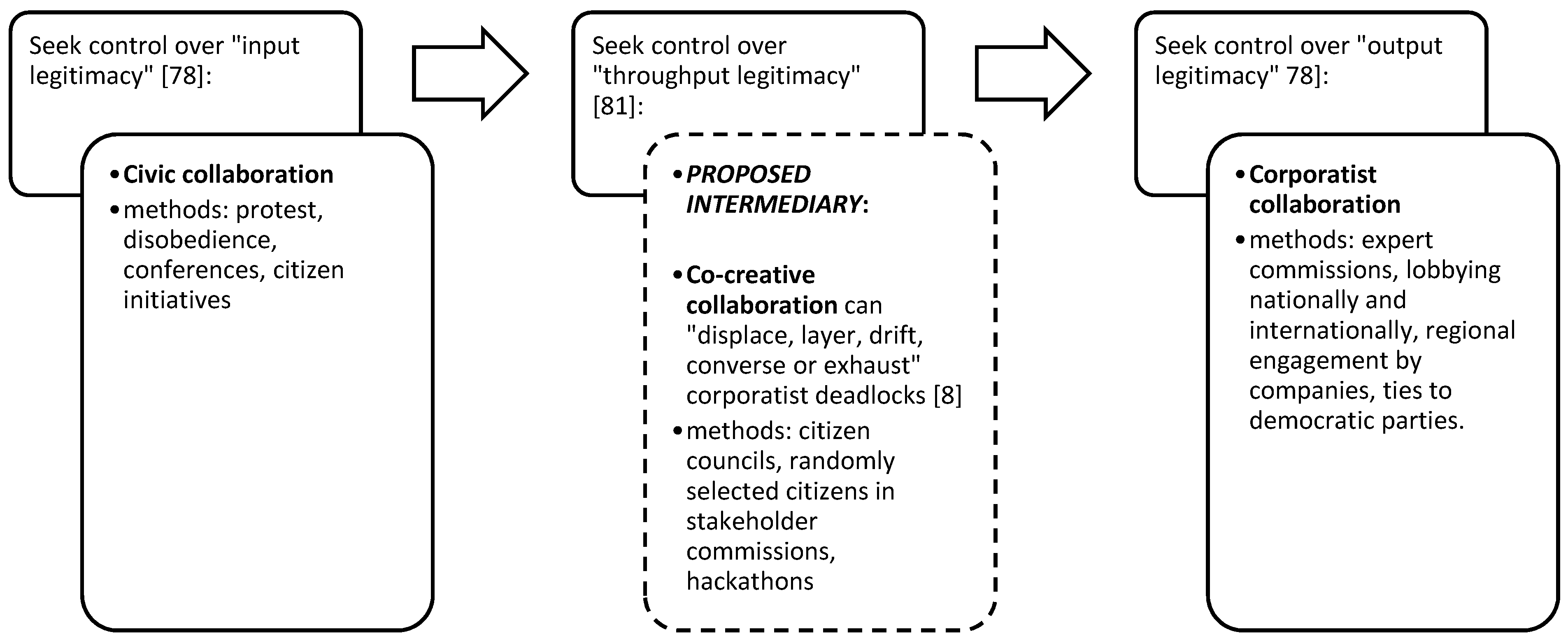

1.3. Concepts of Legitimacy, Collaboration, and Incremental Change

- Displacement occurs “not through explicit revision or amendment of existing arrangements, but rather through shifts in the relative salience of different institutional arrangements within a ‘field’ or ‘system’.”

- Layering “involves active sponsorship of amendments, additions, or revisions to an existing set of institutions.”

- Drift entails that “the world surrounding an institution evolves in ways that alter its scope, meaning, and function.”

- Conversion describes that “(t)he redirection of institutional resources that we associate with conversion may occur through political contestation over what functions and purposes an existing institution should serve”.

- Exhaustion is a form of change “in which behaviors invoked or allowed under existing rules operate to undermine these.”

2. Case Studies: Germany without Coal and Cars?

2.1. First Case: Mobility Transition

- There are movements for bicycle referendums in approximately 30 cities throughout Germany, the first of which was in Berlin and provided the input and legitimacy for a new mobility law. This was then formally legitimized when passed by Berlin’s state parliament in 2018 [65]. Citizens in numerous German cities and federal states have followed this model, accompanying their demands and proposals with continued campaigns entailing various degrees of direct collaboration with politics.

- Movements for car-reduced or car-free neighborhoods are not new in Germany. This can be observed in examples like Freiburg’s Vauban sustainable urban district, which in 2001 already pioneered a car-reduced neighborhood model. More recently, initiatives such as “Verkehrsberuhigter Samariterkiez” (Traffic-calmed Samariter Neighborhood) and “Autofreier Wrangelkiez” (Car-Free Wrangel Neighborhood) have sprouted up in Berlin, pursuing car-reduced and car-free living concepts from the bottom up. In Hamburg, “Ottensen Macht Platz” (Ottensen Makes Room) is a project in which citizens have produced plans for achieving change in their immediate vicinity, and initiated collaboration with local government to work towards their implementation. Thus, with ideas and expectations coming from citizens, expectations for the resulting policies in the form of changed infrastructure have been demanded and endowed with legitimacy.

- Tangible mobility concepts are also responsible for new forms of collaboration with politics and civil society. The “Radbahn Berlin” project, developed by a civil society group to utilize space beneath an elevated city-center train line throughout three city districts, has prompted a further example of collaboration between citizens and government [66]. The initiators are currently collaborating with government at the municipal, state, and federal levels, and have received a federal grant of more than two million euros (some of which goes directly to their governmental partners at the municipal level) to implement their proposal along a test section of the route. Again, legitimacy derives from civil actors producing an idea which at various moments is acknowledged by the elected government through certain outcomes, such as a funding grant or an invitation to pursue the project collaboratively.

- In the city of Wuppertal, a citizens’ group collaborated with the city government for more than ten years to realize a 20-kilometer pedestrian and bicycle path along the Nordbahntrasse, a former railway alignment. Not only was the group largely responsible for the initial concept, and for establishing it on the political agenda, they were also involved in organizing its funding, and even assumed responsibility for constructing parts of the project and involving the community in maintaining the route after its completion. The completed greenway has provided a safe option for active transport, as it links major parts of the city. This has led to an increase in active transport, particularly cycling [67].

2.2. Second Case: Coal Phase-Out

- By the end of 2038, the coal phase-out should have been completed (by 2035, if possible). Coal-fired power plant capacity of 12.5 gigawatts (GW) is to be taken off-grid by 2022 (coal-based capacity is presently 42.6 GW).

- Further interim targets have also been defined, but these remain relatively vague. Compensation for rising electricity prices is also planned.

- The affected federal states are to receive structural change aid amounting to 40 billion euros over the next 20 years.

- One characteristic of the German energy transition is that it has long had a strongly decentralized character. New energy cooperatives, municipal utilities, farmers, or private individuals have contributed to the democratization of energy supply. The “Bündnis Bürgerenergie” (“Citizens’ Energy Alliance”) was founded in 2014 in response to growing attacks on the system of guaranteed feed-in tariffs that was fundamental to Germany’s Renewable Energy Sources Act (EEG). This alliance focuses on stronger networking among the various actors (citizen financiers, energy producers, co-owners, etc.) that have forged a decentralized and democratized renewable energy system in many parts of Germany; organizes an annual civic energy convention; and also lobbies for the democratic and co-creative transformation of the energy system.

- Since 2015, the Ende Gelände alliance has regularly organized campaigns of civil disobedience. The alliance is strongly inspired in its forms of action by the anti-nuclear movement, and has managed to position coal energy at the center of public attention and establish new forms of cooperation through broad networking with other, less radical actors as well as local people from Hambach Forest. The resulting pressure became so great that the German Government decided, within the framework of the coalition negotiations in 2018, to settle the issue by establishing the above mentioned Coal Commission [71,76].

- In recent years, the Hambach Forest has become a symbol of resistance to coal-fired power plants, directed against the state’s coal policy, the operating company RWE, and the IGBCE trade union. The latter has repeatedly spoken out against a coal withdrawal and, despite various dialogue formats, has a rather conflictual relationship with those activists occupying treehouses in the Hambach Forest. Nevertheless, the activists are supported by large sections of the local population. In this respect, actions concerned with the future of the forest have brought about new alliances that stand for a different, less domineering and environmentally destructive form of energy production.

- The “Grüne Liga” (Green League) was founded in 1990 out of the East German environmental movement, which was predominantly supported by the Church. It currently comprises four state associations, among others in Brandenburg and Saxony. Grüne Liga has long campaigned against the expansion of coal mining in the Lusatia region, and is well networked with civil society alliances in the other German lignite regions. Against the background of the heated political debate in Lusatia, Grüne Liga plays an important role in resistance to lignite extraction and in shaping sustainable structural change in the Lusatian mining areas.

3. Analysis: Democratic Pitfalls of Corporatist and Civic Collaboration

4. Proposal: Co-Creation Can Leverage Shifts in Environmental Policy

- First, co-creation can contribute to the “displacement” of corporatist collaboration by shifting the focus towards civic constituencies. Mini-publics—particularly in the form of citizens’ councils—offer possibilities for establishing arenas in which policy-makers can seek advice or find support for civic agendas that may be not be congruent with, find support for, or have the creative opportunity to be developed in constellations with strong industry and union input. For this to occur, it is advisable to shape co-creative processes in a way that they can capture the attention of diverse fractions of society, and create transparency as regards the procedural rules of the policy-making process itself. This transparency is a precondition to enable people to identify with the participating mini-public and to build or question their own convictions with regard to the issue(s) at hand.

- Second, co-creation can be a strategy of “layering” because it adds another formation on top of pre-existing citizen groups, but can also be added to more traditional forms of stakeholder consultation. Expert commissions, for instance, can be complemented by randomly selected citizens or civic organizations that have an option to provide alternative perspectives that can qualify or contextualize the advice from those expert commissions. For this to occur, however, it is advisable to shape co-creative processes in ways that consider the systemic imbalance of pre-existing knowledge and experience among randomly selected citizens compared with that of experts and professionals. Besides providing access to all relevant knowledge and facts, a mini-public needs to be effectively guarded as a safe space for open deliberation among its members. Otherwise, such a council can easily become prone to instrumentalization and manipulation. In cases where a mini-public is asked to deliberate on controversial topics, this type of process can also include hearings for representatives of the conflicting positions, enabling them to present their arguments directly to the mini-public.

- Third, co-creation can contribute to “drift” by changing the conditions under which corporatist forms of collaboration operate. For instance, institutionalized forms of civic collaboration, such as hackathons involving participants from various backgrounds, can pick up on the advice of expert commissions and create policy proposals that push for an independent reading of the results. For this to occur, it is advisable to shape co-creative processes in ways that facilitate the emergence of mutual trust among the different actors involved, which can most likely be achieved by designing processes over longer periods of time and with a sufficient focus on group dynamics and repeated opportunities to gain insights into one another’s positions.

- Fourth, co-creation can foster a kind of “conversion” by integrating expertise that is free to embrace or reject to an ambitious transformation, while at the same time considering and prioritizing the needs of affected civic communities. For this to occur it is advisable to shape co-creative processes in a manner that enables civic perspectives to be incorporated sufficiently early to allow their values to be integrated into tangible future visions.

- Finally, co-creation can facilitate a form of change by encouraging a broad variety of actors to articulate local coping strategies to an interested and politically relevant audience. For this to occur, it is advisable to shape co-creative processes in a way that recognizes the principle of subsidiarity whenever possible. This means that in many circumstances it is preferable to work with several local mini-publics attached to local decision-making, rather than a single group at a higher level of governance. In this way, local contexts can be respected and adequately integrated into solutions.

5. Co-Creation in Just Transition Processes

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kemp, R.; van Lente, H. The dual challenge of sustainability transitions. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2011, 1, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatch, M.T. The politics of global warming in Germany. Environ. Politics 1995, 4, 415–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmieg, G.; Meyer, E.; Schrickel, I.; Herberg, J.; Caniglia, G.; Vilsmaier, U.; Laubichler, M.; Hörl, E.; Lang, D. Modeling normativity in sustainability: A comparison of the sustainable development goals, the Paris agreement, and the papal encyclical. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 785–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keohane, R.O.; Victor, D.G. Cooperation and discord in global climate policy. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2016, 6, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helgenberger, S.; Jänicke, M. Mobilizing the co-benefits of Climate Change Mitigation. IASS Working Paper, 2017. Retrieved on 2 December 2019. Available online: http://publications.iass-potsdam.de/pubman/item/escidoc:2348917:6/component/escidoc:2666888/IASS_Working_Paper_2348917.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2020).

- Weber, H. Politics of ‘leaving no one behind’: Contesting the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals agenda. Globalizations 2017, 14, 399–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasanoff, S. Product, Process, or Programme: Three cultures and the regulation of biotechnology. In Resistance to New Technology; Bauer, M., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995; pp. 311–331. [Google Scholar]

- Blühdorn, I. “Myths of Empowerment and Ecologisation. On the Rematerialisation of post-materialist Politics.” ECPR, Joint Sessions, Copenhagen: 14–19. Retrieved at 2 December 2019. Available online: https://ecpr.eu/Filestore/PaperProposal/e51d15b9-5df7-4f96-9b47-7af85091dfd0.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2020).

- Streeck, W.; Thelen, K. Introduction: Institutional change in advanced political economies. In Beyond Continuity: Institutional Change in Advanced Political Economies; Streeck, W., Thelen, K., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005; pp. 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Battilana, J.; Dorado, S. Building sustainable hybrid organizations: The case of commercial microfinance organizations. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 1419–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Offe, C. Erneute Lektüre: Die» Strukturprobleme «nach 33 Jahren. In Claus Offe, Strukturprobleme des kapitalistischen Staates: Aufsätze zur Politischen Soziologie, Veränderte Neuausgabe; Borcher, J., Lessenich, S., Eds.; Campus: Frankfurt/Main, Germany, 2006; pp. 181–196. [Google Scholar]

- Brand, K.W. Transformationen der Ökologiebewegung. In Neue Soziale Bewegungen; Ansgar Klein, A., Legrand, H.-J., Leif, T., Eds.; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 1999; pp. 237–256. [Google Scholar]

- Raphael, L. Jenseits von Kohle und Stahl: Eine Gesellschaftsgeschichte Westeuropas nach dem Boom; Suhrkamp Verlag: Frankfurt/Main, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Offe, C. Einleitung: Reformbedarf und Reformoptionen der Demokratie. In Demokratisierung der Demokratie: Diagnosen und Reformvorschläge; Offe, C., Ed.; Campus: Frankfurt/Main, Germany, 2003; pp. 9–23. [Google Scholar]

- Toke, D. Ecological modernisation, social movements and renewable energy. Environ. Politics 2011, 20, 60–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aykut, S.C. Energy futures from the social market economy to the Energiewende: The politicization of West German energy debates, 1950–1990. In The Struggle for the Long-Term in Transnational Science and Politics; Andersson, J., Rindzeviciute, E., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015; pp. 63–91. [Google Scholar]

- Della Porta, D.; Mattoni, A. Social movements. Int. Encycl. Political Commun. 2016, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, F. Climate Crisis and the Democratic Prospect: Participatory Governance in Sustainable Communities; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hopke, J.E. Hashtagging politics: Transnational anti-fracking movement Twitter practices. Soc. Media Soc. 2015, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandbergen, D. “We are sensemakers”: The (anti-) politics of smart city co-creation. Public Cult. 2017, 29, 539–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Essen, E. Environmental disobedience and the dialogic dimensions of dissent. Democratization 2017, 24, 305–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dow, J.M. Environmental civil disobedience. In The Palgrave Handbook of Philosophy and Public Policy; Boonin, D., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Olcese, C.; Saunders, C.; Tzavidis, N. In the streets with a degree: How political generations, educational attainment and student status affect engagement in protest politics. Int. Sociol. 2014, 29, 525–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlström, M.; Kocyba, P.; De Vydt, M.; de Moor, J. Fridays for Future: A New Generation of Climate Activism. IProtest for a Future: Composition, Mobilization and Motives of the Participants in Fridays For Future Climate Protests on 15 March 2019 in 13 European Cities. pp. 6–18. Available online: eprints.keele.ac.uk/6571/7/20190709_Protest%20for%20a%20future_GCS%20Descriptive%20Report.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2020).

- Mauser, W.; Klepper, G.; Rice, M.; Schmalzbauer, B.S.; Hackmann, H.; Leemans, R.; Moore, H. Transdisciplinary global change research: The co-creation of knowledge for sustainability. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2013, 5, 420–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trencher, G.; Yarime, M.; McCormick, K.B.; Doll, C.N.; Kraines, S.B. Beyond the third mission: Exploring the emerging university function of co-creation for sustainability. Sci. Public Policy 2013, 41, 151–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquilani, B.; Silvestri, C.; Ioppolo, G.; Ruggieri, A. The challenging transition to bio-economies: Towards a new framework integrating corporate sustainability and value co-creation. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 4001–4009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacoste, S. Sustainable value co-creation in business networks. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2016, 52, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandsen, T.; Verschuere, B. Co-Production and Co-Creation Engaging Citizens in Public Services; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Goodin, R.E.; Dryzek, J.S. Deliberative impacts: The macro-political uptake of mini-publics. Politics Soc. 2006, 34, 219–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sintomer, Y. From Deliberative to Radical Democracy? Sortition and Politics in the 21th Century. Legislature by Lot. An Alternative Design for Deliberative Governance; Verso: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, G.; Wales, C. Citizens’ juries and deliberative democracy. In Democracy as Public Deliberation; d’Entreves, M., Ed.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2018; pp. 157–177. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell, D.M.; O’Malley, E.; Suiter, J. Deliberative democracy in action Irish-style: The 2011 We The Citizens Pilot Citizens’ Assembly. Ir. Political Stud. 2013, 28, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, M.E.; Pearse, H. Designing Deliberative Democracy: The British Columbia Citizens’ Assembly; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hess, D.J. Sustainability transitions: A political coalition perspective. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurrelmann, A.; Schneider, S.; Steffek, J. (Eds.) Legitimacy in An Age of Global Politics; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lipset, S.M. Political Man. The Social Bases of Politics; Heinemann: London, UK; Melbourne: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Zürn, M. Global governance and legitimacy problems. Gov. Oppos. 2004, 39, 260–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdam, D.; Tarrow, S.; Tilly, C. Dynamics of Contention; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hess, D.J. Incumbent-led transitions and civil society: Autonomous vehicle policy and consumer organizations in the United States. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 151, 119825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kungl, G. Stewards or sticklers for change? Incumbent energy providers and the politics of the German energy transition. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2015, 8, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fligstein, N.; McAdam, D. A Theory of Fields; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Brand, U. “Transformation” as a new critical orthodoxy: The strategic use of the term “Transformation” does not prevent multiple crises. Gaia-Ecol. Perspect. Sci. Soc. 2016, 25, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürtler, K.; Rivera, M. New departures—Or a spanner in the works? Exploring narratives of impact-driven sustainability research. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölscher, K.; Wittmayer, J.M.; Loorbach, D. Transition versus transformation: What’s the difference? Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2018, 27, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WBGU. World in Transition. A Social Contract for Sustainability; German Advisory Council on Global Change (WBGU): Berlin, Germany, 2011; Available online: www.wbgu.de/fileadmin/templates/dateien/veroeffentlichungen/hauptgutachten/jg2011/wbgu_jg2011_en.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2020).

- Geels, F.W. Socio-technical transitions to sustainability: A review of criticisms and elaborations of the Multi-Level Perspective. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2019, 39, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Voß, J.P.; Grin, J. Innovation studies and sustainability transitions: The allure of the multi-level perspective and its challenges. Res. Policy 2010, 39, 435–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, T. Struggles in European Union energy politics: A gramscian perspective on power in energy transitions. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 48, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, U. Mapping and navigating transitions: The multi-level perspective compared with arenas of development. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 996–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Hess, D.J. Ordering theories: Typologies and conceptual frameworks for sociotechnical change. Soc. Stud. Sci. 2017, 47, 703–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doganova, L.; Laurent, B. Keeping things different: Coexistence within European markets for cleantech and biofuels. J. Cult. Econ. 2016, 9, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DIW. Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung: Verkehr in Zahlen 2014/2015; BMVI: Berlin, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Allianz Pro Schiene. Deutschland investiert zu wenig in die Schieninfrastruktur; Berlin, Germany, 2017. Available online: https://www.allianz-pro-schiene.de/themen/infrastruktur/investitionen/ (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- Köder, L.; Burger, A. Umweltschädliche Subventionen in Deutschland, Aktualisierte Ausgabe 2016; Umweltbundesamt: Dessau-Roßlau, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Schwedes, O. Verkehr im Kapitalismus; Westfälisches Dampfboot: Münster, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schwedes, O.; Ruhrort, L. Länderverkehrspolitik. In Die Politik der Bundesländer. Staatstätigkeit im Vergleich, 2nd ed.; Hildebrandt, A., Wolf, F., Eds.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2008; pp. 235–256. [Google Scholar]

- Schwedes, O. The field of transport policy. An initial approach. Ger. Policy Stud. 2011, 7, 7–41. [Google Scholar]

- Bundestag, D. Kontakte der Bundesregierung zur Automobilindustrie; Antwort der Bundesregierung auf die Kleine Anfrage der Abgeordneten Herbert Behrens, Caren Lay, Eva Bulling-Schröter, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion DIE LINKE. 18. Wajlperiode, Drucksache 18/12060. 05.07; Bundestag: Berlin, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sternkopf, B.; Nowack, F. Lobbying: Zum Verhältnis von Wirtschaftsinteressen und Verkehrspolitik. In Handbuch Verkehrspolitik; Schwedes, O., Canzler, W., Knie, A., Eds.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2016; pp. 381–399. [Google Scholar]

- Lijphart, A. Patterns of Democracy: Government forms and Performance in Thirty-Six Countries, 2nd ed.; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- BMUB. Umweltbewusstsein in Deutschland 2016: Ergebnisse einer Repräsentativen Bevölkerungsumfrage; Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz, Bau und Reaktorsicherheit: Berlin, Germany, 2017; Available online: https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/sites/default/files/medien/1968/publikationen/umweltbewusstsein_in_deutschland_2016_barrierefrei.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2017).

- Burmeister, K. Umkämpfte Arbeit in der Automobil-Industrie. Das Beispiel Automotiv-Cluster in Baden-Württemberg. Prokla Z. Für Krit. Soz. 2019, 49, 277–294. [Google Scholar]

- Walgrave, S.; van Aelst, P. The contingency of the mass media’s political agenda setting power: Toward a preliminary theory. J. Commun. 2006, 56, 88–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Schneidemesser, D.; Herberg, J.; Stasiak, D. Wissen auf die Straße. Kokreative Verkehrspolitik jenseits der “Knowledge-Action-Gap”. In Das Wissen der Nachhaltigkeit. Herausforderungen zwischen Forschung und Beratung; Lüdtke, N., Henkel, A., Eds.; Oekom: Munich, Germany, 2018; pp. 107–128. [Google Scholar]

- Paper Planes, E.V. Radbahn Berlin: Future Visions for the Ecomobile City; JOVIS Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Widmann, R. Das Projekt Nordbahntrasse Wuppertal: Eine Bürgerinitiative Entwickelt und Baut Gemeinsam mit der Stadtverwaltung Einen Fuß- und Radweg. Praxisbericht im Nationaler Radverkehrsplan, Fahrradportal. Deutsches Institut für Urbanistik gGmbH. 2016. Available online: https://nationaler-radverkehrsplan.de/de/praxis/eine-buergerinitiative-entwickelt-und-baut (accessed on 20 January 2020).

- Beck, S. The challenges of building cosmopolitan climate expertise: The case of Germany. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2012, 3, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hustedt, T. Analyzing policy advice. The case of climate policy in Germany. Cent. Eur. J. Public Policy 2013, 7, 88–110. [Google Scholar]

- Brand, U. In der Wachstumsfalle. Die Gewerkschaften und der Klimawandel. Blätter für deutsche und international Politik 2019, 7, 79–88. Available online: https://www.blaetter.de/ausgabe/2019/juli/in-der-wachstumsfalle (accessed on 2 April 2020).

- Jungk, R. The Nuclear State; John Calder: London, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bossel, H.; Krause, F.; Müller-Reismann, K.-F. Energiewende: Wachstum und Wohlstand ohne Erdöl und Uran; S. Fischer: Frankfurt/Main, Germany, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Bosse, J. Zivilgesellschaftlicher Protest und seine Wirkung. Es liegt was in der Luft. Politische Ökologie 2019, 37, 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Oei, P.-Y.; Brauers, H.; Herpich, P.; Hirschhausen, C.; von Prahl, A.; Wehnert, T.; Bierwirth, A.; Fischedick, M.; Kurwan, J.; Mersmann, F.; et al. Phasing Out Coal in the German Energy Sector: Interdependencies, Challenges and Potential Solutions; Berlin, Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung; Wuppertal Institut für Klima, Umwelt, Energie; Ecologic Institute: Berlin, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Öko-Institut. Die Deutsche Kohle-Verstromung bis 2030. Eine Modellgestützte Analyse der Empfehlungen der Kommission “Wachstum, Strukturwandel und Beschäftigung”; Öko-Institut: Berlin, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sander, H. Ende Gelände: Anti-Kohle-Proteste in Deutschland. Forsch. Soz. Beweg. 2017, 30, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engels, A.; Hüther, O.; Schäfer, M.; Held, H. Public climate-change skepticism, energy preferences and political participation. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 1018–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharpf, F.W. Demokratietheorie Zwischen Utopie und Anpassung; Universitätsverlag: Konstanz, Germany, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Trade Unions in the Green Economy. Working for the Environment; Rathzel, N., Uzzell, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Soder, M.; Niedermoser, K.; Theine, H. Beyond growth: New alliances for socio-ecological transformation in Austria. Globalizations 2018, 15, 520–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, V.A. Democracy and legitimacy in the European Union revisited: Input, output and ‘throughput’. Political Stud. 2013, 61, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, A.; Grayson, K. The intersecting roles of consumer and producer: A critical perspective on co-production, co-creation and prosumption. Sociol. Compass 2008, 2, 963–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ILO (International Labour Organization). Resolution Concerning Sustainable Development, Decent Work and Green Jobs; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Herberg, J.; Haas, T.; Oppold, D.; von Schneidemesser, D. A Collaborative Transformation beyond Coal and Cars? Co-Creation and Corporatism in the German Energy and Mobility Transitions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3278. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083278

Herberg J, Haas T, Oppold D, von Schneidemesser D. A Collaborative Transformation beyond Coal and Cars? Co-Creation and Corporatism in the German Energy and Mobility Transitions. Sustainability. 2020; 12(8):3278. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083278

Chicago/Turabian StyleHerberg, Jeremias, Tobias Haas, Daniel Oppold, and Dirk von Schneidemesser. 2020. "A Collaborative Transformation beyond Coal and Cars? Co-Creation and Corporatism in the German Energy and Mobility Transitions" Sustainability 12, no. 8: 3278. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083278

APA StyleHerberg, J., Haas, T., Oppold, D., & von Schneidemesser, D. (2020). A Collaborative Transformation beyond Coal and Cars? Co-Creation and Corporatism in the German Energy and Mobility Transitions. Sustainability, 12(8), 3278. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083278